Abstract

Many cancers offer an extended window of opportunity for early detection and therapeutic intervention that could lead to a reduction in cause-specific mortality. The pursuit of early detection in screening settings has resulted in decreased incidence and mortality for some cancers (e.g., colon and cervical cancers), and increased incidence with only modest or no effect on cause-specific mortality in others (e.g., breast and prostate). Whereas highly sensitive screening technologies are better at detecting a number of suspected “cancers” that are indolent and likely to remain clinically unimportant in the lifetime of a patient, defined as overdiagnosis, they often miss cancers that are aggressive and tend to present clinically between screenings, known as interval cancers. Unrecognized overdiagnosis leads to overtreatment with its attendant (often long-lasting) side effects, anxiety, and substantial financial harm. Existing methods often cannot differentiate indolent lesions from aggressive ones or understand the dynamics of neoplastic progression. To correctly identify the population that would benefit the most from screening and identify the lesions that would benefit most from treatment, the evolving genomic and molecular profiles of individual cancers during the clinical course of progression or indolence must be investigated, while taking into account an individual’s genetic susceptibility, clinical and environmental risk factors, and the tumor microenvironment. Practical challenges lie not only in the lack of access to tissue specimens that are appropriate for the study of natural history, but also in the absence of targeted research strategies. This commentary summarizes the recommendations from a diverse group of scientists with expertise in basic biology, translational research, clinical research, statistics, and epidemiology and public health professionals convened to discuss research directions.

Overdiagnosis is defined as diagnosis of a disease that will cause neither symptoms nor death during the lifetime of an individual (Welch and Black, 2010). Since overdiagnosis typically occurs in the setting of screening for disease, it is frequently defined as detection of disease by screening that in the absence of screening would not have been diagnosed within the lifetime of the patient (Etzioni et al., 2003). Overdiagnosis occurs in settings in which there is an undetected reservoir of cancer that is progressing so slowly or not progressing at all that it causes neither symptoms nor death and can only be detected by screening (Welch and Black, 2010). By their very nature, screening programs have almost always favored detection of slowly- or non-progressing disease and may miss rapidly progressing cancers. Although screening tests have been successful for some cancers (e.g., colon and cervical), others have shown only modest or no clear benefit (e.g., breast and prostate).

The National Cancer Institute’s Division of Cancer Prevention convened a Think Tank meeting entitled “Defining the Molecularly-Informed Natural History of Neoplasms,” in March 2012, to evaluate and address the challenges to reduce the burden of “overdiagnosis” on physicians, patients, and our healthcare system. Two previous articles have been published based on this Think Tank (Esserman et al., 2013, 2014). These articles included the evidence for overdiagnosis of cancers and “precancerous” conditions across many organ sites, including breast, prostate, lung, thyroid, skin, esophagus, as well as cancers in which screening was halted. For example, screening for childhood neuroblastoma using urine catecholamines was discontinued when it was shown that screening failed to decrease mortality (Esserman et al., 2014), and it was recognized that the screen detected neuroblastomas underwent spontaneous regression in the absence of medical or surgical interventions (Yamamoto et al., 1998; Tanaka et al., 2000). In another instance, the Word Health Organization (WHO) revised the classification of urothelial tumors to remove the word “carcinoma” from the lowest grade tumors (Esserman et al., 2014). These articles also recommended using the term “indolent lesion of epithelial origin (IDLE)” for those conditions that are known to be unlikely to cause harm, reserving the word “cancer” for lesions with a reasonable likelihood of lethal progression if left untreated (Esserman et al., 2013, 2014).

It has become increasingly evident that cancers are a collection of complex heterogeneous diseases with distinct genomic and molecular characteristics and clinical courses, even for the same cancer type. Two breast cancer patients may have tumors with vastly different biology and natural history that will require different approaches to therapy. Current screening technologies and histopathological analysis are not sufficient to address the true problem and we need better diagnoses for cancers that clarify their future clinical courses through improved understanding of the natural history and biology of tumor development.

Occurrence of Overdiagnosis

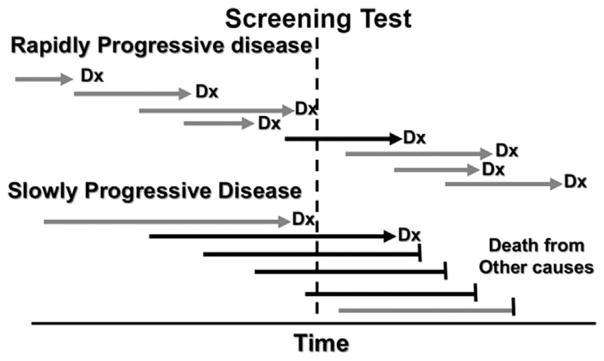

A pressing issue for early detection is the ability to distinguish life-threatening from non-life-threatening cancers. Many clinicians do not readily accept overdiagnosis as a possibility and consider any diagnosis of cancer to be life-threatening and/ or in need of therapeutic interventions. This is understandable given the medical dictionary definition of cancer when many of them were in training was “a neoplastic disease that natural course of which is fatal” (Welch and Black, 2010). However, current screening tests are better at detecting slow- than fast-growing tumors, which is termed length-biased sampling (Kramer, 2004) (Fig. 1). If the screen-detected tumors are slow-growing enough, or even non-growing, they will not cause symptoms or death during the person’s lifetime.

Fig. 1.

Length-biased Sampling. Each cancer has a window of opportunity during which it can be detected by screening. However, screening tests are more effective at detecting slowly growing neoplasms than those that progress rapidly. In some cases, the neoplasms progress so slowly that the patient dies of undetected cancer or the patient never develops a consequential cancer and dies of unrelated causes (“overdiagnosis”). Critical features of length-biased sampling include optimization of timing for the window of opportunity to detect a rapidly progressing neoplasm before it progresses beyond the stage in which it can be cured and developing biomarker tests that distinguish rapidly evolving cancers from those that evolve slowly or not at all.

The use of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing to detect prostate cancer is an example of a cancer screening test that resulted in a marked increase in incidence of early stage, indolent cancers, not fully compensated by a subsequent reduction in late stage cancers or mortality benefit in the United States (Andriole et al., 2012). Most clinicians accept that this has led to a substantial amount of overtreatment with its attendant harms (Thompson et al., 2007; Esserman et al., 2009, 2013). Although active surveillance is often an option for early, localized prostate lesions, physicians may not feel comfortable leaving patients untreated when they are unsure of the clinical course of the lesion, leading to overtreatment (Klotz et al., 2010; Newcomb et al., 2010). Approximately 20–70% of screen-detected prostate cancers are overdiagnosed and subject to radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy or hormone therapy can than cause urinary incontinence, erectile dysfunction, and complications from surgery (Fowler et al., 1993; Potosky et al., 2004; Sanda et al., 2008). Autopsy studies have found a large reservoir of unsuspected prostate cancer in men who died of unrelated causes (Thompson et al., 2007). Screening can dip into this reservoir and detect indolent tumors and tumors of ill-defined biology and natural history (Schoenborn et al., 2013).

With increases in screening mammography, the incidence of breast cancer detection has also increased, including detection of non-invasive ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and early invasive lesions (Esserman et al., 2009, 2013). However, this has not been accompanied by any reduction in metastatic disease, strongly suggesting overdiagnosis of clinically insignificant cancers (Bleyer and Welch, 2012). According to some reports, more than 25% of breast cancers detected on mammograms could represent overdiagnosis (Welch and Black, 2010). A randomized trial conducted in Canada with 25-year follow-up data reported that 22% of screen-detected invasive breast cancers were overdiagnosed and there was no mortality benefit of annual mammography screening (Miller et al., 2014). Another recent study showed a range of reported benefits and harms of mammography screening among 1,000 women aged 50 years who are screened annually for 10 years in the United States: 0.3–3.2 will avoid death from breast cancer, 490–670 will receive at least one false-positive recall, 70–100 will have a false-positive biopsy, and 3–14 will be overdiagnosed and overtreated that may result in long-lasting side effects, anxiety, and substantial financial harm (Welch and Passow, 2014). Physicians need to have open discussions with patients to help them understand the harms and benefits of screening and the options that are available for positive test results so that the patients can make well-informed decisions about their health.

A Paradigm Shift in the Model of Neoplastic Progression

The linear model of carcinogenesis—the concept of cancer as a series of gradually advancing abnormal steps that lead to cancer and death—has dominated medical discourse (Croswell et al., 2010). This led to the logical deduction that early detection of these abnormalities must be of benefit to the affected individuals by providing an opportunity to “break the chain” of disease progression. However, this model has led to overdiagnosis of benign changes that have no effect on mortality and missed diagnosis of lethal early disease. For example, patients with Barrett’s esophagus undergoing endoscopic screening are detected with and treated for Barrett’s metaplasia that is presumed to give rise to esophageal adenocarcinoma, yet 90–95% of the patients die of causes unrelated to the esophagus, and there is evidence that the metaplasia may be protective (Reid et al., 2010).

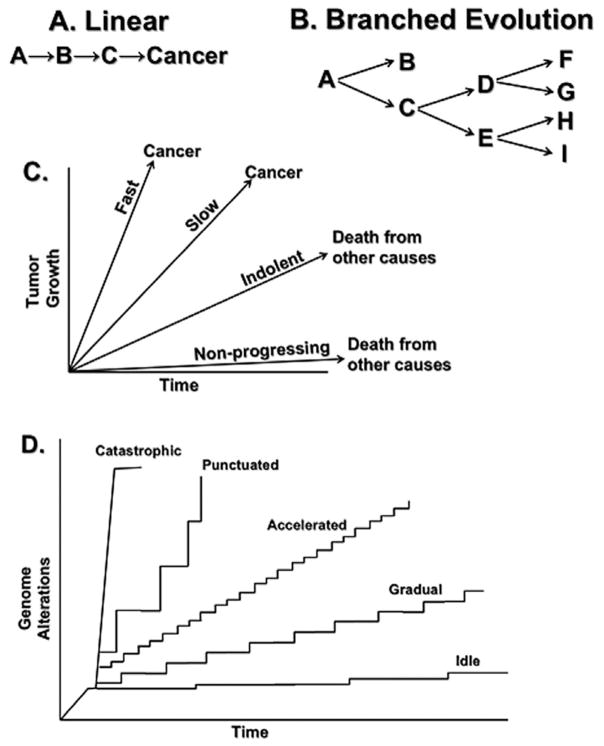

Figure. 2 illustrates the dynamics of neoplastic progression under the old linear gradualism model and the new “branched evolution” model that has emerged from modern genomic evaluations. Recent studies have provided evidence that neoplastic progression in multiple organ sites can occur rapidly by “punctuated evolution” involving chromosome instabilities that can reshuffle the genome in one or a few catastrophic mitoses (Stephens et al., 2011; Carter et al., 2012; Baca et al., 2013). These disease dynamics have not been studied carefully especially regarding time intervals and the somatic genomic evolutionary processes that lead to different cancer outcomes (Gould and Eldredge, 1993; Esserman et al., 2009; Welch and Black, 2010; Navin et al., 2011; Stephens et al., 2011; Berger et al., 2012; Carter et al., 2012; Imielinski et al., 2012; Baca et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2014). In Barrett’s esophagus, such catastrophic and punctuated evolution can be detected by whole genome doublings and chromosome instability two to four years before diagnosis of cancer, raising the question of the optimal prevention approach given this timeframe (Li et al., 2014). Similar findings in other cancers, including recent evidence that more than 50% of advanced breast, colorectal, lung, and ovarian cancers also show evidence of a history of punctuated chromosome instability followed by whole-genome doublings (Carter et al., 2012) and nearly 40% of all human cancers show evidence of whole-genome doublings (Zack et al., 2013), indicate that underlying biological principles that may extend across organs have not yet been recognized (Stephens et al., 2011; Carter et al., 2012; Baca et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2014). For example, what tumor- and tissue-based genomic or molecular markers characterize the more aggressive behavior of cancers that progress rapidly, tend to present clinically between screenings, and are missed by the most sensitive available screening tests (known as interval cancers)? For mathematical modeling of cancers, population trends and genomic data can be explored and integrated to infer hypotheses about a cellular hierarchy underlying cancer progression. Priority areas for research include de-linking diagnosis with treatment, designing non-invasive diagnostics, and active surveillance trials (Newcomb et al., 2010).

Fig. 2.

Dynamics of Cancer Progression. Panel A. The linear model of disease has had a major influence on medicine for more than a century. In its recent versions, it is postulated that there is a slow, gradual, linear occurrence of molecular abnormalities before the development of cancer that provides a long “window of opportunity” for early detection. This model predicts that interrupting any event (e.g., B) in the linear pathway will prevent progression. Panel B. Recent advances in genome technologies have reported that cancers arise by “branched evolution.” In some cases, such as in Barrett’s esophagus, an early branch leads to a state in which the esophageal metaplasia can remain stable for long periods of time (A→B). However, in other cases, progression is branching. In this case inhibiting one step (e.g., C→D) will not necessarily block progression, which can proceed through C→E. Panel C. Progression of a neoplasm over time has typically been represented as a linear series of measures, such as tumor growth or size, that increase at different rates in a linear fashion. Panel D. Recent results from genome analyses of tumors have provided evidence that genomic alterations may occur at vastly different rates. For example, point mutations may occur slowly resulting in relatively gradual rates of progression (“gradual evolution”), or an “IDLE” condition, but exposure to environmental mutagens such as tobacco smoke or the presence of inherited conditions that increase mutation rate can lead to “accelerated evolution” of cancer. Finally, recent evidence from genomic studies of advanced cancers have reported evidence that some cancers may develop by “punctuated” jumps that alter large regions of chromosomes such as chromosome instability (an increase in the rate of gain or loss of whole chromosomes or large regions of chromosomes). Catastrophic evolution, including chromothripsis (chromosome shattering) and whole-genome doublings, may occur in a single event; for example whole-genome doublings have been observed in nearly 40% of cancers sequenced by TCGA. In some cases, a series of events may accelerate progression. For example, Barrett’s esophagus develops chromosome instability (“punctuated evolution”) within four years of the diagnosis of cancer and genome doublings (“catastrophic evolution”) within two years of cancer diagnosis. Multiple other cancers, including those of the breast, lung, colon and ovary, also undergo a similar sequence of events but the timing relative to the onset of cancer has not yet been determined. IDLE =indolent lesion of epithelial origin.

Biological Determinants of Cancer Lethality: Understanding the Natural History and Dynamic Evolution of Tumors

Studies must integrate clinical as well as genomic and molecular variables into our understanding of the underlying biology of neoplastic evolution. Important biological questions include:

What are the strategies for defining the prevalence and taxonomy of occult and overdiagnosed cancers?

Intervention is often triggered by a static picture of the detected lesion based on its histopathology rather than the knowledge about the temporal dynamics of progression as they relate to the underlying tumor biology. What could be investigated to define the natural history of lesions at the genomic, molecular, and biological levels, thereby complementing histology and cytology?

Improved management strategies will require a better understanding of the determinants of cancer lethality, how they evolve, characteristics of the diagnosed lesions, and the development of reliable tools and strategies for early detection. To achieve this goal, multidisciplinary approaches are necessary to understand the dynamics of cancer pathogenesis and progression. Cancer is a disease of multicellular organisms that have multiple levels of defense against cancer, including organ structures with epithelial architectures that limit mutation selection in intestines, skin, and other organs (Zhang et al., 2001), and the microenvironment among many others. Host-level determinants may also play an important role (e.g., immune surveillance, age, environment exposure).

These interactions can be seen in studies of very early lesions in skin carcinogenesis that show that TP53 mutant keratinocytes undergo clonal expansion by a non-mutational mechanism that allows colonization of adjacent stem cell compartments in which the stem cells without TP53 mutations have undergone UV-induced apoptosis (Brash et al., 2005). Tumor growth is therefore driven by UV-induced apoptosis of adjacent healthy cells, which alters the selective landscape, and also influences the fate determination of stochastic stem cells (Klein et al., 2010). This results in dynamic, stochastic progression with exponential expansions of TP53 mutant clones (Klein et al., 2010). These observations raise the question of the extent to which indolent and aggressive cancers are different subtypes or a result of environmental changes. While genome comparisons provide valuable information, the multifocal and multicentric nature of cancers makes this challenging because cancer genomes have diverse cell populations that underlie somatic cell evolution when exposed to different environmental challenges (Merlo and Maley, 2010; Sprouffske et al., 2011). Because chronic inflammation leads to enhanced mutagenesis and greater genetic diversity, longitudinal studies should include inflammation markers (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). Although inflammation markers would not distinguish between pro- or anti-tumor inflammations, such markers still would be useful (Colotta et al., 2009; Zitvogel et al., 2012).

The difference between indolent and aggressive behavior may not simply rest with the tumor cells, but may be determined by interactions among host, environment, and neoplasm. For example, people who have exposures to environmental mutagens such as ultraviolet light and cigarette smoke or inherit mismatch repair deficiencies have very high mutation rates in some cancers, such as those of the skin, lung, and colon (Imielinski et al., 2012; Vogelstein et al., 2013). Thus, both biological and epidemiological factors need to be considered in evaluating the trajectory of an evolving neoplasm as well as in the design and analysis of studies. A better understanding of these interactions may give information as to the duration of the “window of opportunity” in which a screening test may be effective (Brown and Palmer, 2009). Unfortunately, many current screening tests are unable to detect tumors in this window. These observations raise a number of challenging questions:

How can we systematically define the repertoire of preneo-plastic, premalignant, and “quasi”-malignant lesions that constitute the targets for early detection?

How can we study the selective forces and corresponding selected genotypes that shape the evolution of a cancer during its earliest generations?

How can we systematically define the molecular/cellular characteristics (genetic, epigenetic, cell physiology, signaling profile, metabolism, microenvironment, and immune reaction) of each of these lesions?

What kind of lineage relationships exists among these lesions?

How would one define the life trajectories of each of these lesions—growth rate, genetic, and phenotypic evolution, and corresponding risk of development of clinically significant malignancy?

What are the practical strategies for defining prevalence, taxonomy, and inferring the natural history of occult cancers?

Despite many hypotheses, it is not understood what steps must occur in the progression from single cells to lethal cancer. The natural history of most cancers goes unobserved or undetected until a lethal cancer presents clinically. It is important to understand both the evolving events that lead to lethal cancer and aborted or indolent trajectories that cause neither symptoms nor death. Recent studies in the cervix and esophagus have shown that competitive advantage can fall to residual embryonic cells that remain after most other cells have differentiated (Herfs et al., 2013). For example, in the setting of acid reflux, embryonic cells at the gastroesophageal squamocolumnar junction can be selected for the development of Barrett’s lesions, but only a small fraction of these cases progress to cancer (Wang et al., 2011). Thus, cell populations with the same genotype can yield cancerous cells or not, depending on their environment. Determining the natural history of cancers can also provide novel insights into early detection and prevention (Crum et al., 2012).

The majority of cancer lethality is due to metastasis, but there is confusion concerning the biological processes that lead to death. For example, primary prostate cancer can have prolonged latency periods before metastasizing into bone and lymphatic systems (Chen and Pienta, 2011). Tumors can be conceptualized as ecosystems in which cancer cells are species that co-exist in a complex habitat with other host cells and factors and are capable of behaving analogously to invasive species when they metastasize (Pienta et al., 2008; Chen and Pienta, 2011). This complex ecosystem could be understood by an integrative strategy (e.g., tumor genome and transcriptome) that examines the genomic and transcriptomic diversity of the tumor cell populations, the microenvironment, and relevant genes involved in evolution of survival and proliferation strategies. This would allow multitargeted therapeutic strategies to be developed to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with metastases.

Molecular pathways and genomic interactions that fully explain cancer lethality have not been well studied. Studies clearly indicate that metastasis is important, but lineage analyzes to determine when a tumor develops the capability to cause lethality and whether each cancer cell or metastatic event has this potential are important, unanswered questions. It is difficult to explain selection of host lethality on an evolutionary basis. Therefore, a better understanding of communications between tumor cells and their environment and what metabolic traits might underlie cancer lethality is needed.

Many cancers, such as pancreatic and ovarian, are not detected until they are at advanced stages with low cure rates using current approaches (Vogelstein et al., 2013). A systematic analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Pan-Cancer mutation data set that included 3,281 tumors across 12 tumor types found that the average number of point mutations and small indels in significantly mutated genes varied between two and six (Kandoth et al., 2013). Mathematical modeling of mutation data suggest that there may be windows of opportunity for early detection; for example, it has been estimated that it takes two decades for an initiated pancreatic tumor cell to evolve to metastatic disease (Yachida et al., 2010; Vogelstein et al., 2013). To address these challenges, better screening methods are needed for early detection, and therefore, it is important to define and characterize the clonal architecture of precursor lesions that exist during the treatable window (Vogelstein et al., 2013).

Summary: Open Debates on the Biological Underpinning of Overdiagnosis and Its Implication for Consequential Cancers

There are debates as to how to recognize overdiagnosed lesions and the Think Tank meeting was organized by the National Cancer Institute to address these challenges. The charge to the meeting included discussions of the (1) natural history and biology of screen-detected lesions to assess overdiagnosed and interval (missed) cancers, and strategies that include an emphasis on identifying molecular signatures that distinguish aggressive vs non-aggressive cancers, and (2) molecularly-informed natural history of tumor development to aid in the discovery of biomarkers for early detection and to distinguish aggressive vs non-aggressive cancers. Recommendations from the participants—a diverse group of scientists with expertise in basic biology, translational research, clinical research, statistics, epidemiology, and public health professionals—for the required resources (Box 1) and scientific opportunities (Box 2) have been summarized in this commentary.

Box 1. Needed Resources for Studying the Biology and Natural History of Cancer.

Research approaches to study the magnitude of overdiagnosis in specific populations using existing NIH resources (e.g., surveillance, epidemiology, and end results [SEER], National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [NHANES]) and other resources that provide information on cancers detected by different methods with varying prognoses (e.g., screen-detected, interval-detected, and symptom-detected).

Strategies to understand overdiagnosis and interval (missed) cancers include collections of well-annotated normal, neoplastic, and tumor tissues that are both screen- and symptom-detected cancers. Support collection of surgical and autopsy specimens/tissues, imaging, and biological specimens obtained during screening, surveillance, and treatment over time to study the natural history of cancers.

Animal models with strain-specific behaviors, unique human models, and immunologically-susceptible individuals are also needed to study the selective forces shaping the evolution of cancer in its earliest generations.

Tissue registries, long-term longitudinal studies including cohorts and control arms of randomized trials.

Box 2. Identified Scientific Opportunities in Studying the Biology and Natural History of Cancer.

Implement strategies to study the natural history of cancers through tissue registries, modeling, and long-term longitudinal studies.

Understand genomic and microenvironmental determinants that distinguish indolent tumors that remain stable from aggressive cancers (e.g., metastatic).

Consider host and environmental factors in clarifying the natural history of a tumor including cell of origin, obesity, microbiome/chronic infection, inflammation, physical activity, supplements, aging, medications such as aspirin, DNA repair enzyme polymorphisms and immune response.

Identify molecular and genomic predictors of aggressive lesions with well-designed experiments and modeling that includes time in the equation. Natural history studies must examine tumor dynamics over time, not at a single time point.

-

Develop cross-sectional data with annotated samples; animal models with strain-specific behaviors; host differences (e.g., age); unique human models; and immunologically-susceptible individuals to study the selective forces shaping the evolution of cancer in its earliest generations. The following study designs could help identify molecular markers to understand morbidity/mortality of untreated tumors:

Tracking tumors utilizing delayed management algorithms.

Interval versus screen-detected cancers.

Repositories of incidentally detected tumors.

Identification of reproducible tumor subsets in specific sites that are not removed and can be monitored.

Repositories of incidentally detected tumors.

Follow cohorts of willing patients who do not undergo treatment to collect investigative longitudinal data (e.g., annotated biological specimens, annual imaging, medical records) and analysis at the close of study with appropriate blinding of investigators to understand tumor dynamics and trajectory.

Study developmental biology and evolutionary processes that interact to promote mutations or constrain somatic neoplastic evolution by DNA repair mechanisms promoting survival; gene interactions permitting faulty repair (e.g., BRCA/TP53); gene upregulation conferring advantage (e.g., glucose transporters); longevity; organ-specific susceptibility; and tolerating aneuploidy/genomic instability. Study designs could utilize autopsy tissue.

Undertake DNA sequencing and proteomic analysis of precursor lesions, circulating tumor cells, and host niches to clarify the selection pressures that influence a tumor’s phenotypic trajectory.

Carry out studies of the anatomy and networking of biomarkers between cells; functional imaging; and imaging of spatiotemporal modeling of tissues. Modeling is required to merge various datasets and to consider the characteristics of tumor cells in a holistic way.

Work towards computational understanding of phenotypic trajectories, the extent to which mathematical models are sensitive to assumptions.

Conduct studies to identify determinants of cancer lethality and whether they appear in defined lineages.

It was recognized that overdiagnosis and overtreatment can cause physical, emotional, and financial harms to patients and steps must be taken to minimize them (Croswell et al., 2010). The consensus was to have a deeper understanding of tumor biology, which can be gained by investigating the dynamic molecular patterns of tumor cells along with their surrounding macro- and microenvironment (e.g., epithelial-stromal interactions and interplay with the host’s immune system) as they transition from normal to proliferating cancer cells, start to invade the surrounding tissues and metastasize to distant organ sites. The changes must be put in the context of hereditary, clinical, and environmental risk factors of individuals. This knowledge may allow prediction of clinical course of progression and help develop better tools for discriminating cancers that are clinically important from those that are not. The end points that we currently measure, such as tumor grade, invasion, migration, proliferation, and apoptosis, are far too crude for precise discrimination. The main objective of the meeting was to provide evidence-based avenues for research based on new concepts that have emerged during and after the Think Tank meeting to achieve sufficient understanding and implement necessary measures to reduce overdiagnosis and overtreatment. Studies of less invasive treatments for suspected overdiagnosed lesions should be explored to reduce the frequency and severity of adverse events. Since lesion behavior is determined by the tumor cells themselves, as well as interaction with the surrounding tissue microenvironment, the focus of research strategies should not be restricted to the abnormal-appearing cells. Identifying overdiagnosis involves both biological and epidemiological research methods (Khoury et al., 2013). Biological research generates hypotheses about underlying mechanisms and associated molecular markers, while epidemiological research is required to assess whether those markers can actually predict risk. A key strategy is to develop biomarkers that can distinguish aggressive cancers from non-aggressive cancers that are detected by imaging and other modalities. Testing hypotheses about predictive markers and models can be achieved via observing people over time in the absence of treatment in cohort studies (Galipeau et al., 2007) and can sometimes be piggy-backed on to clinical trials (Paik et al., 2004). Progress, however, has been hampered by the lack of understanding of the natural history of cancers, which may also help understand the somatic genomic evolutionary dynamics of tumors. The application of new tools in molecular biology, genomics, proteomics, immunology, and computational tools may provide new insight into the natural histories of different types of cancers and their precursors when appropriate. In addition, strong institutional support for clinically annotated tissue specimens for all types of cancers and other biomaterials (e.g., blood, serum, stool, tumors, other body fluids) will be needed, especially in reference to mode of detection (screen- vs. symptom- and interval-detected) along with other relevant demographic information to aid in studies to distinguish molecular differences between screen-detected and symptom-detected cancers.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all those who participated and provided their time and expertise at the Think Tank meeting organized by the National Cancer Institute’s Division of Cancer Prevention in March, 2012.

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to declare. Opinions expressed in this Commentary are those of the authors and do not represent official positions of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or the National Institutes of Health.

Authors’ contributions: All authors participated in the preparation of the manuscript and the decision to submit for publication.

Literature Cited

- Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL, Buys SS, Chia D, Church TR, Fouad MN, Isaacs C, Kvale PA, Reding DJ, Weissfeld JL, Yokochi LA, O’Brien B, Ragard LR, Clapp JD, Rathmell JM, Riley TL, Hsing AW, Izmirlian G, Pinsky PF, Kramer BS, Miller AB, Gohagan JK, Prorok PC, Team PP. Prostate cancer screening in the randomized Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial: Mortality results after 13 years of follow-up. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:125–132. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baca SC, Prandi D, Lawrence MS, Mosquera JM, Romanel A, Drier Y, Park K, Kitabayashi N, Macdonald TY, Ghandi M, Van Allen E, Kryukov GV, Sboner A, Theurillat JP, Soong TD, Nickerson E, Auclair D, Tewari A, Beltran H, Onofrio RC, Boysen G, Guiducci C, Barbieri CE, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko A, Carter SL, Saksena G, Voet D, Ramos AH, Winckler W, Cipicchio M, Ardlie K, Kantoff PW, Berger MF, Gabriel SB, Golub TR, Meyerson M, Lander ES, Elemento O, Getz G, Demichelis F, Rubin MA, Garraway LA. Punctuated evolution of prostate cancer genomes. Cell. 2013;153:666–677. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger MF, Hodis E, Heffernan TP, Deribe YL, Lawrence MS, Protopopov A, Ivanova E, Watson IR, Nickerson E, Ghosh P, Zhang H, Zeid R, Ren X, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko AY, Wagle N, Sucker A, Sougnez C, Onofrio R, Ambrogio L, Auclair D, Fennell T, Carter SL, Drier Y, Stojanov P, Singer MA, Voet D, Jing R, Saksena G, Barretina J, Ramos AH, Pugh TJ, Stransky N, Parkin M, Winckler W, Mahan S, Ardlie K, Baldwin J, Wargo J, Schadendorf D, Meyerson M, Gabriel SB, Golub TR, Wagner SN, Lander ES, Getz G, Chin L, Garraway LA. Melanoma genome sequencing reveals frequent PREX2 mutations. Nature. 2012;485:502–506. doi: 10.1038/nature11071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleyer A, Welch HG. Effect of three decades of screening mammography on breast-cancer incidence. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1998–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1206809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brash DE, Zhang W, Grossman D, Takeuchi S. Colonization of adjacent stem cell compartments by mutant keratinocytes. Semin Cancer Biol. 2005;15:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown PO, Palmer C. The preclinical natural history of serous ovarian cancer: Defining the target for early detection. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter SL, Cibulskis K, Helman E, McKenna A, Shen H, Zack T, Laird PW, Onofrio RC, Winckler W, Weir BA, Beroukhim R, Pellman D, Levine DA, Lander ES, Meyerson M, Getz G. Absolute quantification of somatic DNA alterations in human cancer. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:413–421. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen KW, Pienta KJ. Modeling invasion of metastasizing cancer cells to bone marrow utilizing ecological principles. Theor Biol Med Model. 2011;8:36. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-8-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colotta F, Allavena P, Sica A, Garlanda C, Mantovani A. Cancer-related inflammation, the seventh hallmark of cancer: Links to genetic instability. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1073–1081. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croswell JM, Ransohoff DF, Kramer BS. Principles of cancer screening: Lessons from history and study design issues. Semin Oncol. 2010;37:202–215. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum CP, McKeon FD, Xian W. The oviduct and ovarian cancer: Causality, clinical implications, and “targeted prevention. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;55:24–35. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31824b1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esserman L, Shieh Y, Thompson I. Rethinking screening for breast cancer and prostate cancer. JAMA. 2009;302:1685–1692. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esserman LJ, Thompson IM, Jr, Reid B. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment in cancer: An opportunity for improvement. JAMA. 2013;310:797–798. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.108415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esserman LJ, Thompson IM, Reid B, Nelson P, Ransohoff DF, Welch HG, Hwang S, Berry DA, Kinzler KW, Black WC, Bissell M, Parnes H, Srivastava S. Addressing overdiagnosis and overtreatment in cancer: A prescription for change. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e234–e242. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70598-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etzioni R, Urban N, Ramsey S, McIntosh M, Schwartz S, Reid B, Radich J, Anderson G, Hartwell L. The case for early detection. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:243–252. doi: 10.1038/nrc1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler FJ, Jr, Barry MJ, Lu-Yao G, Roman A, Wasson J, Wennberg JE. Patient-reported complications and follow-up treatment after radical prostatectomy. The National Medicare Experience: 1988–1990 (updated June 1993) Urology. 1993;42:622–629. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(93)90524-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galipeau PC, Li X, Blount PL, Maley CC, Sanchez CA, Odze RD, Ayub K, Rabinovitch PS, Vaughan TL, Reid BJ. NSAIDs modulate CDKN2A, TP53, and DNA content risk for future esophageal adenocarcinoma. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e67. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould SJ, Eldredge N. Punctuated equilibrium comes of age. Nature. 1993;366:223–227. doi: 10.1038/366223a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herfs M, Vargas SO, Yamamoto Y, Howitt BE, Nucci MR, Hornick JL, McKeon FD, Xian W, Crum CP. A novel blueprint for “top down” differentiation defines the cervical squamocolumnar junction during development, reproductive life, and neoplasia. J Pathol. 2013;229:460–468. doi: 10.1002/path.4110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imielinski M, Berger AH, Hammerman PS, Hernandez B, Pugh TJ, Hodis E, Cho J, Suh J, Capelletti M, Sivachenko A, Sougnez C, Auclair D, Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Cibulskis K, Choi K, de Waal L, Sharifnia T, Brooks A, Greulich H, Banerji S, Zander T, Seidel D, Leenders F, Ansen S, Ludwig C, Engel-Riedel W, Stoelben E, Wolf J, Goparju C, Thompson K, Winckler W, Kwiatkowski D, Johnson BE, Janne PA, Miller VA, Pao W, Travis WD, Pass HI, Gabriel SB, Lander ES, Thomas RK, Garraway LA, Getz G, Meyerson M. Mapping the hallmarks of lung adenocarcinoma with massively parallel sequencing. Cell. 2012;150:1107–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandoth C, McLellan MD, Vandin F, Ye K, Niu B, Lu C, Xie M, Zhang Q, McMichael JF, Wyczalkowski MA, Leiserson MD, Miller CA, Welch JS, Walter MJ, Wendl MC, Ley TJ, Wilson RK, Raphael BJ, Ding L. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature. 2013;502:333–339. doi: 10.1038/nature12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoury MJ, Lam TK, Ioannidis JP, Hartge P, Spitz MR, Buring JE, Chanock SJ, Croyle RT, Goddard KA, Ginsburg GS, Herceg Z, Hiatt RA, Hoover RN, Hunter DJ, Kramer BS, Lauer MS, Meyerhardt JA, Olopade OI, Palmer JR, Sellers TA, Seminara D, Ransohoff DF, Rebbeck TR, Tourassi G, Winn DM, Zauber A, Schully SD. Transforming epidemiology for 21st century medicine and public health. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:508–516. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TM, Laird PW, Park PJ. The landscape of microsatellite instability in colorectal and endometrial cancer genomes. Cell. 2013;155:858–868. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein AM, Brash DE, Jones PH, Simons BD. Stochastic fate of p53-mutant epidermal progenitor cells is tilted toward proliferation by UV B during preneoplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:270–275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909738107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz L, Zhang L, Lam A, Nam R, Mamedov A, Loblaw A. Clinical results of long-term follow-up of a large, active surveillance cohort with localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:126–131. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer BS. The science of early detection. Urol Oncol. 2004;22:344–347. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2003.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Galipeau PC, Paulson TG, Sanchez CA, Arnaudo J, Liu K, Sather CL, Kostadinov RL, Odze RD, Kuhner MK, Maley CC, Self SG, Vaughan TL, Blount PL, Reid BJ. Temporal and Spatial Evolution of Somatic Chromosomal Alterations: A Case-Cohort Study of Barrett’s Esophagus. Cancer Prev Res. 2014;7:114–127. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-13-0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlo LM, Maley CC. The role of genetic diversity in cancer. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:401–403. doi: 10.1172/JCI42088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AB, Wall C, Baines CJ, Sun P, To T, Narod SA. Twenty five year follow-up for breast cancer incidence and mortality of the Canadian national breast screening study: Randomised screening trial. BMJ. 2014;348:g366. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navin N, Kendall J, Troge J, Andrews P, Rodgers L, McIndoo J, Cook K, Stepansky A, Levy D, Esposito D, Muthuswamy L, Krasnitz A, McCombie WR, Hicks J, Wigler M. Tumor evolution inferred by single-cell sequencing. Nature. 2011;472:90–94. doi: 10.1038/nature09807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb LF, Brooks JD, Carroll PR, Feng Z, Gleave ME, Nelson PS, Thompson IM, Lin DW. Canary Prostate Active Surveillance Study: Design of a multi-institutional active surveillance cohort and biorepository. Urology. 2010;75:407–413. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.05.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paik S, Shak S, Tang G, Kim C, Baker J, Cronin M, Baehner FL, Walker MG, Watson D, Park T, Hiller W, Fisher ER, Wickerham DL, Bryant J, Wolmark N. A multigene assay to predict recurrence of tamoxifen-treated, node-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2817–2826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pienta KJ, McGregor N, Axelrod R, Axelrod DE. Ecological therapy for cancer: Defining tumors using an ecosystem paradigm suggests new opportunities for novel cancer treatments. Transl Oncol. 2008;1:158–164. doi: 10.1593/tlo.08178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potosky AL, Davis WW, Hoffman RM, Stanford JL, Stephenson RA, Penson DF, Harlan LC. Five-year outcomes after prostatectomy or radiotherapy for prostate cancer: The prostate cancer outcomes study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1358–1367. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid BJ, Li X, Galipeau PC, Vaughan TL. Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma: Time for a new synthesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:87–101. doi: 10.1038/nrc2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, Sandler HM, Northouse L, Hembroff L, Lin X, Greenfield TK, Litwin MS, Saigal CS, Mahadevan A, Klein E, Kibel A, Pisters LL, Kuban D, Kaplan I, Wood D, Ciezki J, Shah N, Wei JT. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1250–1261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenborn JR, Nelson P, Fang M. Genomic profiling defines subtypes of prostate cancer with the potential for therapeutic stratification. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:4058–4066. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprouffske K, Pepper JW, Maley CC. Accurate reconstruction of the temporal order of mutations in neoplastic progression. Cancer Prev Res. 2011;4:1135–1144. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens PJ, Greenman CD, Fu B, Yang F, Bignell GR, Mudie LJ, Pleasance ED, Lau KW, Beare D, Stebbings LA, McLaren S, Lin ML, McBride DJ, Varela I, Nik-Zainal S, Leroy C, Jia M, Menzies A, Butler AP, Teague JW, Quail MA, Burton J, Swerdlow H, Carter NP, Morsberger LA, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Follows GA, Green AR, Flanagan AM, Stratton MR, Futreal PA, Campbell PJ. Massive genomic rearrangement acquired in a single catastrophic event during cancer development. Cell. 2011;144:27–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T, Matsumura T, Iehara T, Sawada T. Risk of unfavorable character among neuroblastomas detected through mass screening. The Japanese infantile neuroblastoma cooperative study. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2000;35:705–707. doi: 10.1002/1096-911x(20001201)35:6<705::aid-mpo48>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson IM, Lucia MS, Tangen CM. Commentary: The ubiquity of prostate cancer: echoes of the past, implications for the present: “what has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.” ECCLESIASTES 1:9. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:287–289. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA, Jr, Kinzler KW. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013;339:1546–1558. doi: 10.1126/science.1235122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Ouyang H, Yamamoto Y, Kumar PA, Wei TS, Dagher R, Vincent M, Lu X, Bellizzi AM, Ho KY, Crum CP, Xian W, McKeon F. Residual embryonic cells as precursors of a Barrett’s-like metaplasia. Cell. 2011;145:1023–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch HG, Black WC. Overdiagnosis in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:605–613. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch HG, Passow HJ. Quantifying the benefits and harms of screening mammography. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:448–454. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yachida S, Jones S, Bozic I, Antal T, Leary R, Fu B, Kamiyama M, Hruban RH, Eshleman JR, Nowak MA, Velculescu VE, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA. Distant metastasis occurs late during the genetic evolution of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2010;467:1114–1117. doi: 10.1038/nature09515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Hanada R, Kikuchi A, Ichikawa M, Aihara T, Oguma E, Moritani T, Shimanuki Y, Tanimura M, Hayashi Y. Spontaneous regression of localized neuroblastoma detected by mass screening. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1265–1269. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zack TI, Schumacher SE, Carter SL, Cherniack AD, Saksena G, Tabak B, Lawrence MS, Zhang CZ, Wala J, Mermel CH, Sougnez C, Gabriel SB, Hernandez B, Shen H, Laird PW, Getz G, Meyerson M, Beroukhim R. Pan-cancer patterns of somatic copy number alteration. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1134–1140. doi: 10.1038/ng.2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Remenyik E, Zelterman D, Brash DE, Wikonkal NM. Escaping the stem cell compartment: Sustained UVB exposure allows p53- mutant keratinocytes to colonize adjacent epidermal proliferating units without incurring additional mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13948–13953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241353198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zitvogel L, Kepp O, Galluzzi L, Kroemer G. Inflammasomes in carcinogenesis and anticancer immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:343–351. doi: 10.1038/ni.2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]