Abstract

Background

Although Treatment-as-Prevention (TasP) efforts are a new cornerstone of efforts to respond to the HIV/AIDS pandemic, their effects among people who use drugs (PWUD) have not been fully evaluated. This study characterizes temporal trends in CD4 cell count at ART initiation and rates of virologic response among HIV-positive PWUD during a TasP initiative.

Methods

We used data on individuals initiating ART within a prospective cohort of PWUD linked to comprehensive clinical records. Using multivariable linear regression, we evaluated the relationship between CD4 count prior to ART initiation and year of initiation and time to HIV-1 RNA viral load < 50 copies/mL following initiation using Cox proportional hazards modeling.

Results

Among 355 individuals, CD4 count at initiation rose from 130 to 330 cells/mL from 2005 to 2013. In multivariable regression, initiation year was significantly associated with higher CD4 count (β = 29.5 cells per year, 95% CI: 21.0–37.9). Initiating ART at higher CD4 counts was significantly associated with optimal viral response (Adjusted Hazard Ratio = 1.13 per 100 cells/mL increase, 95% CI: 1.05–1.22).

Discussion

Increases in CD4 cell count at initiation over time was associated with superior virologic response, consistent with the aims of the TasP initiative.

Keywords: HIV, antiretroviral therapy, CD4, people who use drugs, illicit drug users, Treatment-as-Prevention

BACKGROUND

For people living with HIV/AIDS, exposure to antiretroviral therapy (ART) is strongly associated with lower rates of HIV/AIDS-associated morbidity and mortality, and decreased likelihood of onward viral transmission (1, 2). However, previous work has shown that HIV-positive people who use drugs (PWUD) exhibit a higher prevalence of sub-optimal HIV/AIDS treatment outcomes, driven by poorer access and adherence to ART (3–5).

In recent years, the evidence-base in support of ART initiation earlier in the disease course, when CD4+ T-cell lymphocyte cell (CD4) counts are higher, has expanded (6–8). A recent systematic review including one randomized controlled trial and 13 observational studies reported that all found a decreased risk of death among individuals who began treatment with CD4 counts of at least 350 cells/ml over study periods ranging from six months to four years (9). Further, mathematical modelling has demonstrated how earlier treatment initiation can reduce community-level viral load and curb the incidence of new infections (10). Most recently, the Strategic Timing of Antiretroviral Treatment (START) trial was halted prematurely after preliminary results showed a considerably diminished risk of adverse AIDS events and serious non-AIDS events associated with immediate ART initiation upon diagnosis compared to delayed initiation at a CD4 cell count below 350 cells/ml (11, 12). In light of this evidence, the World Health Organization recently announced it would recommend that all individuals living with HIV should begin ART immediately after diagnosis, regardless of CD4 cell count (13).

Treatment-as-Prevention (TasP) initiatives aim to improve HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention outcomes through enhanced HIV testing, improved linkage to care, and initiation of ART upon diagnosis (14). By reducing plasma HIV-1 RNA viral load (VL) in people living with HIV to very low levels through the use of ART, the likelihood of onward viral transmission is sharply reduced. In one RCT, the risk of transmission was reduced by 96% in serodiscordant couples who reported three or more sex acts within three-month time frame measured over 1,500 person years (15). Despite accumulating evidence of significant reductions in mortality and morbidity associated with ART use among people living with HIV (16), studies have shown that PWUD are less likely to receive ART than non-drug users and typically start treatment later in the disease course (3, 4, 17). A study conducted among PWUD in a community setting in the United States observed that for each 100 cells/mL increase in CD4 cell count, there was a 15% decrease in probability of ART initiation (18). There is very limited data on the relationship between CD4 cell count at ART initiation and subsequent disease course among PWUD and none, to our knowledge, from settings with TasP-based efforts to scale-up access and adherence to ART. In addition, there are concerns that initiating ART prior to the appearance of symptomatic disease may lead to lower adherence and degraded initial virologic response (19). Using data from an ongoing prospective cohort of community-recruited HIV-positive PWUD linked to comprehensive HIV clinical monitoring and ART dispensation records, we sought to characterize CD4 cell count at ART initiation over time and evaluate patterns of subsequent virologic response during a community-wide TasP-based initiative.

METHODS

To meet these objectives, we used data from the AIDS Care Cohort to evaluate Exposure to Survival Services (ACCESS), an ongoing prospective cohort of people living with HIV/AIDS who use illicit drugs in Vancouver, Canada. The study aims to measure and analyse the behavioural, social, structural and environmental factors that facilitate or impede access and adherence to HIV treatment and thus effect disease progression and viral transmission among people who use drugs. It has been described in detail previously (20). Briefly, individuals were eligible for the study if they were HIV-positive, aged ≥ 18 years and had used illicit drugs other than cannabis at least once in the 30 days prior to the baseline interview. Participants were recruited from community settings by word-of-mouth, postering and snowball sampling focused on the Downtown Eastside (DTES) area of Vancouver, Canada. The site of an explosive outbreak of HIV infection among injection drug users and their sexual partners beginning in the mid-1990s (21), the area has high levels of illicit drug use and poverty as well as an active open drug market. The ACCESS study has been reviewed and approved by the University of British Columbia/Providence Healthcare Research Ethics Board. All participants provided written informed consent and were compensated $30 for each study visit.

Following recruitment, ACCESS participants complete an interviewer-administered questionnaire, which elicits information on lifetime and recent characteristics, behaviours, and exposures. Participants also complete an examination by a study nurse, which includes drawing a blood sample for HIV/AIDS clinical monitoring, including CD4 cell count observations. At six-month intervals, all participants complete follow-up interviews and nursing examinations. At baseline, all individuals provide their personal health number (PHN), a unique and persistent identifier used for medical billing and tracking purposes by the provincial universal health plan. This identifier is also used by study staff to conduct confidential linkages to other administrative databases. Using the PHN, study staff access all HIV/AIDS treatment records held by the British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS (BCCfE) Drug Treatment Program (DTP). The BCCfE provides all HIV/AIDS treatment and care, including medications and clinical monitoring tests, free of charge to all individuals living with HIV in BC through the government’s universal healthcare plan. Through the DTP, a complete retrospective and prospective clinical profile is available for all ACCESS participants. This profile includes all plasma HIV-1 RNA VL observations and CD4 cell counts conducted through the study or as part of regular medical care. This linkage also includes antiretroviral dispensation information, including data on agent, dose, date and location.

In this retrospective study, we included all ACCESS participants who were dispensed their first dose of ART between January 1, 2005 and June 30, 2013, regardless of their date of study recruitment. We excluded all individuals with no CD4 measurements within 180 days prior to ART initiation.

To investigate changes in CD4 cell count at initiation over time, our primary outcome of interest was CD4 cell count at initiation, defined as the last recorded CD4 cell count measurement prior to ART initiation (i.e., baseline.) To investigate patterns of virologic response, our outcome of interest was time to virologic non-detectability, using the date of the first VL observation below 50 copies/mL plasma within the 365 days following ART initiation. The Roche Amplicor Monitor assay [Roche Molecular Systems, Pleasanton, California, USA] was used to determine VL from participant blood samples. The lower limit of detection was 50 copies/mL for the entire study period.

From the linked pharmacy records, we defined a number of explanatory variables, including: the year of the first dispensation of ART (per year later); age at the date of the first ART dispensation (per year older); plasma VL at the time of ART initiation, defined as the last observation prior to ART initiation (per log 10 increase); and whether the first ART regimen contained a protease inhibitor (PI, yes vs. no). Using the list defined by the United States Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (22) we also determined whether the individual had been diagnosed with an AIDS-defining illness prior to initiating ART (ever vs. never). Because we have previously shown it predicts virologic response to ART (23), we also included information on the experience of the physician who prescribed the first ART regimen. For each participant, at the time of ART initiation we calculated how many patients their prescribing physician had previously initiated on ART, dichotomizing at 6 patients (< 6 patients vs. ≥ 6 patients). Previous work has shown that location is a determinant of treatment access and success (24). The postal code associated with the ART dispensation location for each participant was used to determine whether dispensation occurred within the DTES (yes vs. no). We defined postal codes with forward sortation areas of “V6A” or “V6B” as belonging in the DTES. We also defined explanatory variables using time-invariant information gathered during the baseline cohort interview, including: gender (male vs. non-male); self-reported Caucasian ancestry (yes vs. no); and years since first illicit drug use at ART initiation (per year later.)

As a first step, we examined the median CD4 cell count for all individuals initiating ART during each year of the study period. Next, we examined the median values (for other continuous variables) and contingency tables (for categorical variables) stratified by study year. For each variable, we tested for temporal trends using the Cochran-Armitage test (for categorical) or least-squares regression on study year (for continuous variables).

To analyze temporal changes in CD4 cell count at ART initiation, we used linear regression to model the bivariable relationship between CD4 cell count and the year of initiation. We also considered other explanatory variables that have been shown to be associated with treatment engagement in our setting and others, specifically: age at ART initiation, gender, Caucasian ancestry, DTES dispensation, years since initiation of illicit drug use, and HIV MD experience. To obtain an estimate of the linear change in CD4 cell count at ART initiation adjusted for possible confounders, we built a multivariable model using an a priori model-building strategy. Described in detail previously (25), the protocol uses a backwards selection procedure based on the relative change in the value of the coefficient of the primary explanatory variable (i.e., year of initiation). First, we built a multivariable model containing the primary explanatory variables and all secondary explanatory variables with p-values < 0.4 in bivariable analyses. Noting the value of the regression coefficient for year of initiation in the full model, we fit a series of reduced models, each with one explanatory variable removed, noting the value of the regression coefficient for year of initiation in each. Next, we removed the secondary explanatory variable associated with the smallest relative change in the value of the regression coefficient for the primary explanatory variable from the set of secondary explanatory variables and fit a new full model. We continued this iterative process until the smallest relative change exceeded 1%. This procedure to estimate the relationship between a primary explanatory variable and an outcome of interest was first proposed by Greenland and colleagues (26), and has been used in previous analyses within ACCESS (25).

To analyze patterns of initial virologic response to treatment, we first created a categorical variable describing CD4 cell count at initiation (< 200 cells/mL vs. ≥ 200 cells/mL and < 350 cells/mL vs. ≥ 350 cells/mL.) Next, using the Kaplan-Meier estimator, we visually inspected the risk of virologic susppression following treatment initiation, stratified by baseline CD4 cell count category. To analyze the relationship between baseline CD4 cell count and virologic response, we next built a series of Cox proportional hazards regression models. We included a number of explanatory variables that we hypothesized might confound the relationship between baseline CD4 cell count and virologic response, including: age at ART initiation; gender; Caucasian ancestry; baseline VL; presence of an AIDS-defining illness; years since first illicit drug use; DTES dispensation; HIV physician experience; presence of PI in first regimen. All models fit included a term for the baseline VL.

RESULTS

Between December 1, 2005 and June 1, 2013, the study recruited 816 HIV-positive PWUD, including 534 (66%) men, with a mean age of 43 (inter-quartile range [IQR]: 37 – 48) years. Of the 816 participants, 58 (7%) did not initiate ART prior to the end of the study period and 398 initiated ART before January 1, 2005; these individuals were not eligible for this study. Of the remaining 360, 355 (99%) had ≥ 1 CD4 cell count recorded within 180 days of their first study interview and were included in these analyses. Compared to participants who were not included in this study, those included did not differ by self-reported ancestry or gender, however they were significantly younger at baseline (44 vs. 40 years, p < 0.001).

Among the 355 participants, 130 (37%) were non-male and the median age at ART initiation was 41 years. Two hundred people (56%) self-reported Caucasian ancestry. Approximately one-third of the participants received their first ART dispensation at a location in the DTES (106, 30%). Table 1 shows the median CD4 cell counts at ART initiation, along with demographic and drug-use characteristics of the eligible participants, stratified by year of ART initiation. The median cell count at CD4 initiation for the entire study period was 220 cells/mL. Of note, between 2005 and 2013, median CD4 cell count increased from 130 (IQR: 60 – 205) to 330 (IQR: 205 – 430) cells/mL (test for trend: p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Median CD4 cell count at ART initiation and other clinical, demographic and drug-use characteristics, stratified by calendar year of ART initiation among 355 illicit drug users in Vancouver, Canada, 2005 – 2013 (n=355)

| Characteristic | 2005 n (%) |

2006 n (%) |

2007 n (%) |

2008 n (%) |

2009 n (%) |

2010 n (%) |

2011 n (%) |

2012 n (%) |

2013 n (%) |

p-value1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 cell count (per 100 cells/mL) | ||||||||||

| Median (IQR) | 1.30 (0.60 – 2.05) | 1.60 (1.05 – 2.05) | 1.90 (1.25 – 2.45) | 1.90 (0.95 – 2.75) | 2.40 (1.60 – 2.30) | 3.10 (2.40 – 3.80) | 3.80 (2.10 – 5.10) | 3.10 (1.80 – 4.30) | 3.30 (2.05 – 4.30) | < 0.001 |

| Age | ||||||||||

| Median (IQR) | 39 (31 – 47) | 40 (37 – 47) | 41 (34 – 46) | 43 (34 – 48) | 42 (33 – 46) | 42 (36 – 48) | 36 (31 – 42) | 42 (33 – 47) | 45 (38 – 54) | 0.801 |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Non-male | 15 (43) | 12 (30) | 24 (38) | 16 (34) | 12 (23) | 14 (39) | 20 (43) | 10 (43) | 7 (58) | |

| Male | 20 (57) | 28 (70) | 39 (62) | 31 (66) | 41 (77) | 22 (61) | 26 (57) | 13 (57) | 5 (42) | 0.299 |

| Caucasian ancestry | ||||||||||

| No | 15 (43) | 15 (38) | 28 (44) | 22 (47) | 21 (40) | 13 (36) | 21 (46) | 14 (61) | 6 (50) | |

| Yes | 20 (57) | 25 (62) | 35 (56) | 25 (53) | 32 (60) | 23 (64) | 25 (54) | 9 (39) | 6 (50) | 0.331 |

| DTES2 dispensation | ||||||||||

| No | 25 (71) | 25 (62) | 43 (68) | 31 (66) | 37 (70) | 25 (69) | 37 (80) | 15 (65) | 11 (92) | |

| Yes | 10 (29) | 15 (38) | 20 (32) | 16 (34) | 16 (30) | 11 (31) | 9 (20) | 8 (35) | 1 (8) | 0.144 |

| Years of illicit drug use | ||||||||||

| Median (IQR) | 13 (8 – 20) | 17 (10 – 21) | 18 (11 – 26) | 14 (6 – 22) | 16 (6 – 23) | 16 (3 – 26) | 16 (10 – 19) | 11 (8 – 20) | 20 (14 – 28) | 0.823 |

| HIV-1 RNA (per log10 copies/mL plasma) | ||||||||||

| Median (IQR) | 5.0 (4.6 – 5.0) | 5.0 (4.7 – 5.0) | 4.8 (4.3 – 5.0) | 4.8 (4.2 – 5.0) | 4.5 (4.1 – 5.0) | 4.5 (4.0 – 5.1) | 4.4 (3.7 – 4.9) | 4.6 (4.2 – 4.8) | 4.2 (3.2 – 4.8) | < 0.001 |

| PI3 in first regimen | ||||||||||

| No | 8 (29) | 11 (33) | 9 (20) | 10 (26) | 12 (35) | 4 (17) | 4 (11) | 3 (16) | 0 (0) | |

| Yes | 20 (70) | 22 (67) | 36 (80) | 28 (74) | 22 (65) | 20 (83) | 31 (89) | 16 (84) | 8 (100) | 0.255 |

| ADI4 | ||||||||||

| Never | 27 (77) | 36 (90) | 54 (86) | 38 (81) | 45 (85) | 33 (92) | 41 (89) | 21 (91) | 12 (100) | |

| Ever | 8 (23) | 4 (10) | 9 (14) | 9 (19) | 8 (15) | 3 (8) | 5 (11) | 2 (9) | 0 (0) | 0.062 |

Test for trend

Downtown Eastside

Protease Inhibitor

AIDS-defining illness

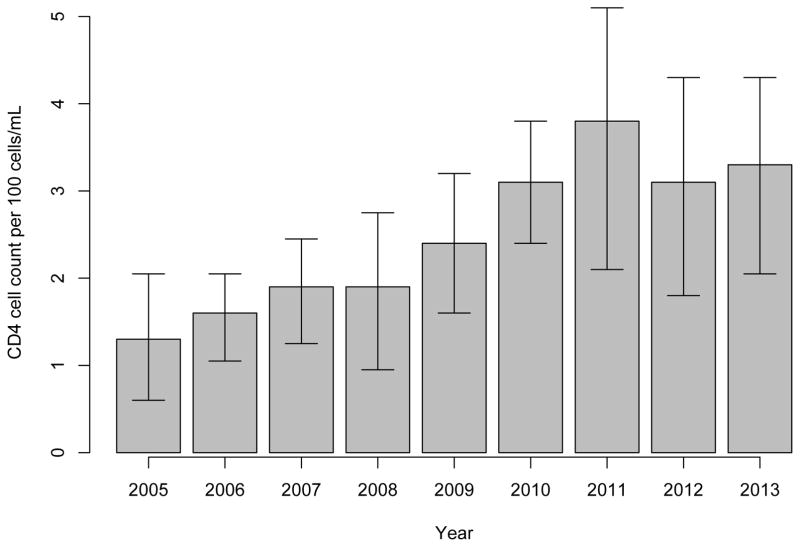

Figure 1 depicts the median CD4 cell count at ART initiation for each year of the study period. We observed a statistically significant upward trend in CD4 cell count at ART initiation from 130 cells/mL in 2005 to 330 cells/mL in 2013, peaking in 2011 with a cell count of 380 cells/mL.

Figure 1.

Median CD4 cell count at ART initiation by calendar year, 2005 to 2013 among 355 HIV-positive illicit drug users

Table 2 presents bivariable and multivariable linear regression analyses of cofounders associated with CD4 cell count at ART initiation. In crude analyses, increasing year of ART initiation was significantly and positively associated with higher CD4 cell count at baseline (β = 31.2, 95% CI: 23.0 – 39.3, p < 0.001). This association was maintained in a multivariable model also adjusted for gender and HIV physician experience. In the adjusted analysis, each later year of ART initiation was associated with a baseline CD4 cell count increase of 29.5 cells/mL (95% CI: 21.0 – 37.9).

Table 2.

Bivariable and multivariable linear regression analyses of factors associated with CD4 cell count at ART initiation among 355 illicit drug users

| Characteristic | Bivariable | Multivariable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| β | 95% CI1 | p-value | β | 95% CI1 | p-value | |

| Year of ART initiation | ||||||

| Per year increase | 31.2 | 23.0 – 39.3 | < 0.001 | 29.5 | 21.0 – 37.9 | < 0.001 |

| Age at ART initiation | ||||||

| Per year increase | −2.1 | −4.3 – 0.1 | 0.067 | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male vs. non-male | −50.3 | −90.3 – −10.3 | 0.014 | −43.6 | −80.9 – −6.3 | 0.022 |

| Caucasian ancestry | ||||||

| Yes vs. no | 1.9 | −37.2 – 41.1 | 0.923 | |||

| DTES2 | ||||||

| Yes vs. no | −15.0 | −57.4 – 27.4 | 0.487 | |||

| Years of illicit drug use | ||||||

| Per year increase | −0.7 | −2.5 – 1.1 | 0.445 | |||

| HIV physician experience | ||||||

| < 6 vs. ≥ 6 patients | 62.8 | 17.6 – 108.0 | 0.007 | 23.1 | −20.8 – 67.0 | 0.301 |

95% Confidence Interval

Downtown Eastside

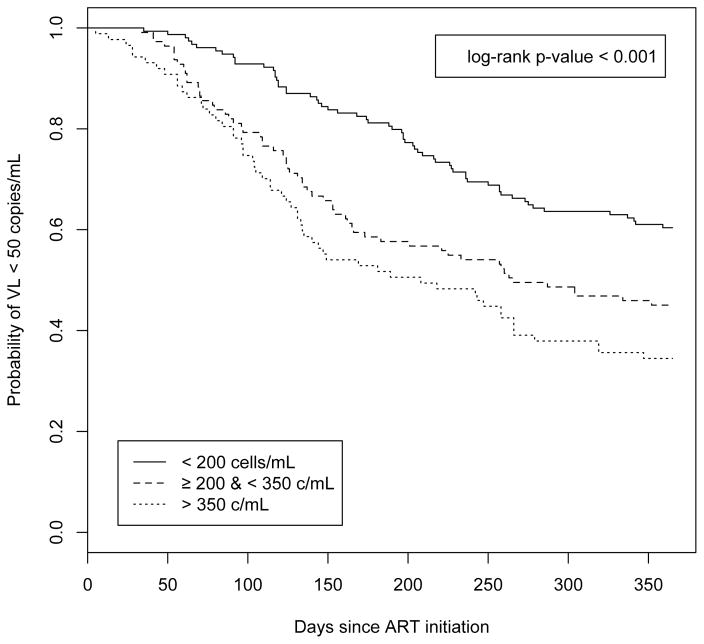

Virologic response following ART initiation stratified by baseline CD4 cell count is presented in the Kaplan-Meier analysis in Figure 2. Initiating ART at CD4 > 350 cells/mL was associated with the swiftest time to a non-detectable VL compared to initiation at lower CD4 strata (i.e., < 200 cells/mL or ≥ 200 cells/mLand ≤ 350 cells/mL). Median time to non-detectable VL among all participants was 341 days; among individuals in the highest CD4 strata, median time was 185 days vs. 265 days among individuals in the middle strata. The difference in survival times was statistically significant in a log-rank test (p < 0.001). In the first 12 months following ART initiation, the probability of reaching a non-detectable VL was > 60% in the group with the highest CD4 levels compared to a probability < 30% in the CD4 < 200 cells/mL group.

Figure 2.

Time to HIV-1 RNA viral load (VL) below 50 copies/mL in the year following antiretroviral therapy initiation (ART), stratified by CD4 cell count at ART initiation (n=355) (< 200 cells/mL vs. ≥ 200 cell/mL & < 350 cell/mL vs. ≥ 350 cell/mL)

The bivariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards models of time to virologic response are shown in Table 3. The final multivariable model violated the proportional hazards assumption and we made efforts to address this, consistent with previously described methods (27, 28). After inspection of the Schoenfeld residuals, we fit a new multivariable model adding an interaction term between time and VL at ART initiation. In this final model, increased CD4 cell count at ART initiation was associated with shorter time to VL non-detectability (Adjusted Hazards Ratio (AHR) = 1.13, 95% CI: 1.05–1.22), adjusted for history of an AIDS-defining illness and VL at ART initiation.

Table 3.

Bivariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards analyses of factors associated with time to plasma HIV-1 RNA viral load < 50 copies/mL in the first year following ART initiation among 355 illicit drug users in Vancouver, Canada, 2005 – 2013

| Characteristic | HR1 | 95% CI2 | p-value | AHR3,6 | 95% CI2 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 cell count 4 | ||||||

| Per 100 cells/mL | 1.20 | 1.12 – 1.28 | < 0.001 | 1.13 | 1.05 – 1.22 | < 0.001 |

| Age at ART initiation4 | ||||||

| Per year older | 1.01 | 0.99 – 1.03 | 0.198 | |||

| Gender4 | ||||||

| Non-male | 1.00 | |||||

| Male | 1.05 | 0.78 – 1.42 | 0.751 | |||

| Caucasian ancestry4 | ||||||

| No | 1.00 | |||||

| Yes | 1.09 | 0.81 – 1.46 | 0.575 | |||

| DTES dispensation4 | ||||||

| No | 1.00 | |||||

| Yes | 0.86 | 0.62 – 1.19 | 0.359 | |||

| Years since illicit drug use initiation4 | ||||||

| Per year increase | 1.00 | 0.99 – 1.02 | 0.532 | |||

| HIV-1 RNA viral load4 | ||||||

| Per log10 increase | 0.68 | 0.58 – 0.79 | < 0.001 | 0.51 | 0.37 – 0.71 | < 0.001 |

| AIDS-defining illness4 | ||||||

| Never | 1.00 | |||||

| Ever | 0.52 | 0.31 – 0.88 | 0.014 | 0.60 | 0.35 – 1.02 | 0.060 |

| PI in first regimen4 | ||||||

| No | 1.00 | |||||

| Yes | 0.92 | 0.69 – 1.23 | 0.571 | |||

| Year of ART initiation4 | ||||||

| Per year increase | 1.35 | 1.27 – 1.44 | < 0.001 | |||

Hazard Ratio

95% Confidence Interval

Adjusted Hazard Ratio

Baseline at ART initiation

First year after ART initiation

Multivariable model also included interaction term for time by HIV-1 RNA viral load at ART initiation

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to characterize trends in CD4 cell counts at ART initiation among HIV-positive PWUD during a community-wide TasP initiative. We observed a statistically significant upward trend in CD4 cell count at ART initiation, increasing 200 cells/mL between 2005 and 2013, from 130 cell/mL to 330 cell/mL. In addition, we observed improved virologic response to treatment among participants initiating ART at higher CD4 cell counts, particularly at CD4 counts > 350 cells/mL.

Previous studies have shown that PWUD face barriers to timely ART initiation (4, 5, 18), resulting in poorer virologic responses and health outcomes (29). Our study offers compelling evidence to suggest that earlier ART uptake among PWUD can be achieved in the setting of a community-wide TasP initiative. In contrast with our findings, work conducted in the United States suggests that while ART initiation is occurring earlier among non-drug using populations (30), this observation does not hold true for PWUD. A study from the AIDS Linked to the IntraVenous Experience (ALIVE) study of injection drug users in Baltimore, United States, showed no significant increase in rates of ART initiation from 1996 to 2008, with high-intensity injection drug use remaining a key barrier to treatment uptake (31). It should be acknowledged that in our setting of British Columbia there are no financial barriers to ART uptake as HIV treatment is provided at no cost, reducing socio-economic barriers to ART initiation that may be present within other international settings, including the United States.

Previous work has shown that PWUD experience a poorer virologic response to ART compared to non-drug using populations (29, 32). This is well explored within the literature and has been attributed to comorbid health conditions, disadvantaged social circumstances, mental illness, addiction and ongoing drug use (4, 33). HIV cohort studies in Switzerland and the United States have shown that non-PWUD and former drug users have higher rates of treatment uptake and improved responses to ART compared to people who actively use drugs (34, 35). Taken together, these studies suggest that illicit drug users face challenges of delayed treatment and thus reduced virological response. Compared to these findings, our study findings suggest that earlier initiation of ART among HIV-positive PWUD is associated with improved virologic response to treatment. These findings highlight the benefit of supporting early access to treatment to improve clinical outcomes among marginalized drug-using communities and curb onward HIV transmission. This study presents a promising outlook for ongoing efforts to engage vulnerable drug-using populations within the cascade of HIV care to reach ambitious UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets.

Our study is the first, to our knowledge, to describe temporal trends in ART initiation among PWUD during a community-wide TasP-based initiative. Our findings suggest a trend toward treatment initiation earlier in the disease course within this cohort, associated with improved virologic outcomes, consistent with the goals of TasP initiatives. However, we caution that additional study is required to understand the possible contribution of different factors to the observed increase, such as improvements in the convenience, tolerability and potency of antiretroviral regimens over time, or the components of the local community-wide TasP campaign, such as changes to clinical HIV/AIDS treatment guidelines and addiction services. Although we did include time since illicit drug use as a covariate in this analysis, we were unable to include some time-updated behavioural data, such as drug-using practices, presence of psychologic co-morbidities and incarceration that have been shown to influence ART initiation and subsequent virologic response (31, 36, 37).

Our study also has other limitations in addition to those mentioned above. First, as our local setting offers HIV/AIDS treatment and care free-of-charge, including all antiretroviral medications, we were unable to consider the possible role played by financial ability on treatment outcomes, an important consideration in studies of HIV treatment outcomes among members of marginalized and vulnerable communities (38). In addition, while we made efforts to recruit participants from community settings and include individuals at all stages of clinical care, we cannot claim that it is fully representative of HIV-positive PWUD in our setting or others.

In conclusion, in this retrospective study involving HIV-positive PWUD initiating ART during a community-wide TasP-based initiative, we observed increasing CD4 cell counts at ART initiation over time. In a multivariable linear regression model, each later year of ART initiation was associated with an increase in 30 CD4 cells/mL. In a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model, higher CD4 cell count at initiation was associated with improved virologic response to treatment. Our results support earlier initiation of ART as a part of efforts to improve HIV/AIDS treatment and care within marginalized, drug-using communities, especially in light of the recently-announced 90-90-90 goals aimed at eliminating the HIV/AIDS pandemic as a significant public health concern

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants for their contribution to the research, as well as current and past researchers and staff.

The ACCESS study is supported by the United States National Institutes of Health (R01-DA021525). This research was undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs program through a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Inner City Medicine, which supports Dr. Evan Wood. Dr. Milloy is supported in part by the US National Institutes of Health (R01DA021525). Dr. Montaner is supported with grants paid to his institution by the British Columbia Ministry of Health and by the US National Institutes of Health (R01DA036307). He has also received limited unrestricted funding, paid to his institution, from Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck, and ViiV Healthcare. Dr. Sophie Patterson is supported by a Study Abroad Studentship from the Leverhulme Trust.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest. Dr. Montaner has received limited unrestricted funding, paid to his institution, from Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck, and ViiV Healthcare.

An early version of this analysis was presented at the 2015 International AIDS Society conference in Vancouver, Canada (MOPDD01)

References

- 1.Bae JW, Guyer W, Grimm K, Altice FL. Medication persistence in the treatment of HIV infection: a review of the literature and implications for future clinical care and research. Aids. 2011;25(3):279–90. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328340feb0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hogg RS, Heath K, Bangsberg D, Yip B, Press N, O’Shaughnessy MV, et al. Intermittent use of triple-combination therapy is predictive of mortality at baseline and after 1 year of follow-up. Aids. 2002;16(7):1051–8. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200205030-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wood E, Kerr T, Zhang R, Guillemi S, Palepu A, Hogg RS, et al. Poor adherence to HIV monitoring and treatment guidelines for HIV-infected injection drug users. HIV medicine. 2008;9(7):503–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grigoryan A, Hall HI, Durant T, Wei X. Late HIV diagnosis and determinants of progression to AIDS or death after HIV diagnosis among injection drug users, 33 US States, 1996–2004. PloS one. 2009;4(2):e4445. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez-Arenas MA, Jarrin I, del Amo J, Iribarren JA, Moreno S, Viciana P, et al. Delay in the initiation of HAART, poorer virological response, and higher mortality among HIV-infected injecting drug users in Spain. AIDS research and human retroviruses. 2006;22(8):715–23. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.22.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walensky RP, Paltiel AD, Losina E, Mercincavage LM, Schackman BR, Sax PE, et al. The survival benefits of AIDS treatment in the United States. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2006;194(1):11–9. doi: 10.1086/505147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitahata MM, Gange SJ, Abraham AG, Merriman B, Saag MS, Justice AC, et al. Effect of early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy for HIV on survival. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;360(18):1815–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lima VD, Reuter A, Harrigan PR, Lourenco L, Chau W, Hull M, et al. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy at high CD4+ cell counts is associated with positive treatment outcomes. Aids. 2015 doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anglemyer A, Rutherford GW, Easterbrook PJ, Horvath T, Vitoria M, Jan M, et al. Early initiation of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: a systematic review. Aids. 2014;28(Suppl 2):S105–18. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, De Cock KM, Williams BG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):48–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Starting antiretroviral treatment early improves outcomes for HIV-infected individuals. National Institutes of Health; 2015. updated May 27, 2015. Available from: http://www.nih.gov/news/health/may2015/niaid-27.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Group ISS. Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy in Early Asymptomatic HIV Infection. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;373(9):795–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Senthilingam M. World Health Organization to recommend early treatment for everyone with HIV. Nature. 2015 Available from: http://www.nature.com/news/world-health-organization-to-recommend-earlytreatment-for-everyone-with-hiv-1.18017.

- 14.Montaner JS, Lima VD, Barrios R, Yip B, Wood E, Kerr T, et al. Association of highly active antiretroviral therapy coverage, population viral load, and yearly new HIV diagnoses in British Columbia, Canada: a population-based study. Lancet. 2010;376(9740):532–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60936-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vlahov D, Galai N, Safaeian M, Galea S, Kirk GD, Lucas GM, et al. Effectiveness of highly active antiretroviral therapy among injection drug users with late-stage human immunodeficiency virus infection. American journal of epidemiology. 2005;161(11):999–1012. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGowan CC, Weinstein DD, Samenow CP, Stinnette SE, Barkanic G, Rebeiro PF, et al. Drug use and receipt of highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected persons in two U.S. clinic cohorts. PloS one. 2011;6(4):e18462. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Celentano DD, Galai N, Sethi AK, Shah NG, Strathdee SA, Vlahov D, et al. Time to initiating highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected injection drug users. Aids. 2001;15(13):1707–15. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200109070-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sood N, Wagner Z, Jaycocks A, Drabo E, Vardavas R. Test-and-treat in Los Angeles: a mathematical model of the effects of test-and-treat for the population of men who have sex with men in Los Angeles County. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2013;56(12):1789–96. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strathdee SA, Palepu A, Cornelisse PG, Yip B, O’Shaughnessy MV, Montaner JS, et al. Barriers to use of free antiretroviral therapy in injection drug users. Jama. 1998;280(6):547–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hogg RS, Heath KV, Strathdee SA, Montaner JS, O’Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT. HIV/AIDS mortality in Canada: evidence of gender, regional and local area differentials. Aids. 1996;10(8):889–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneider E, Whitmore S, Glynn KM, Dominguez K, Mitsch A, McKenna MT, et al. Revised surveillance case definitions for HIV infection among adults, adolescents, and children aged <18 months and for HIV infection and AIDS among children aged 18 months to <13 years--United States, 2008. MMWR Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report Recommendations and reports/Centers for Disease Control. 2008;57(RR-10):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sangsari S, Milloy MJ, Ibrahim A, Kerr T, Zhang R, Montaner J, et al. Physician experience and rates of plasma HIV-1 RNA suppression among illicit drug users: an observational study. BMC infectious diseases. 2012;12:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lima V, Fernandes K, Rachlis B, Druyts E, Montaner J, Hogg R. Migration adversely affects antiretroviral adherence in a population-based cohort of HIV/AIDS patients. Social science & medicine. 2009;68(6):1044–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milloy MJ, Kerr T, Buxton J, Rhodes T, Guillemi S, Hogg R, et al. Dose-response effect of incarceration events on nonadherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy among injection drug users. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2011;203(9):1215–21. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maldonado G, Greenland S. Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. American journal of epidemiology. 1993;138(11):923–36. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kleinbaum DG, Klein M. Survival Analysis: A Self-Learning Text. Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model. Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lucas GM, Cheever LW, Chaisson RE, Moore RD. Detrimental effects of continued illicit drug use on the treatment of HIV-1 infection. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2001;27(3):251–9. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200107010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsu LC, Truong HM, Vittinghoff E, Zhi Q, Scheer S, Schwarcz S. Trends in early initiation of antiretroviral therapy and characteristics of persons with HIV initiating therapy in San Francisco, 2007–2011. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2014;209(9):1310–4. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mehta SH, Kirk GD, Astemborski J, Galai N, Celentano DD. Temporal trends in highly active antiretroviral therapy initiation among injection drug users in Baltimore, Maryland, 1996–2008. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2010;50(12):1664–71. doi: 10.1086/652867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cescon AM, Cooper C, Chan K, Palmer AK, Klein MB, Machouf N, et al. Factors associated with virological suppression among HIV-positive individuals on highly active antiretroviral therapy in a multi-site Canadian cohort. HIV medicine. 2011;12(6):352–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wood E, Kerr T, Tyndall MW, Montaner JS. A review of barriers and facilitators of HIV treatment among injection drug users. Aids. 2008;22(11):1247–56. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282fbd1ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weber R, Huber M, Rickenbach M, Furrer H, Elzi L, Hirschel B, et al. Uptake of and virological response to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected former and current injecting drug users and persons in an opiate substitution treatment programme: the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. HIV medicine. 2009;10(7):407–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2009.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knowlton A, Arnsten J, Eldred L, Wilkinson J, Gourevitch M, Shade S, et al. Individual, interpersonal, and structural correlates of effective HAART use among urban active injection drug users. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2006;41(4):486–92. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000186392.26334.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pence BW, Miller WC, Gaynes BN, Eron JJ., Jr Psychiatric illness and virologic response in patients initiating highly active antiretroviral therapy. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2007;44(2):159–66. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802c2f51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mehta SH, Lucas G, Astemborski J, Kirk GD, Vlahov D, Galai N. Early immunologic and virologic responses to highly active antiretroviral therapy and subsequent disease progression among HIV-infected injection drug users. AIDS care. 2007;19(5):637–45. doi: 10.1080/09540120701235644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riley ED, Moore KL, Haber S, Neilands TB, Cohen J, Kral AH. Population-level effects of uninterrupted health insurance on services use among HIV-positive unstably housed adults. AIDS care. 2011;23(7):822–30. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.538660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]