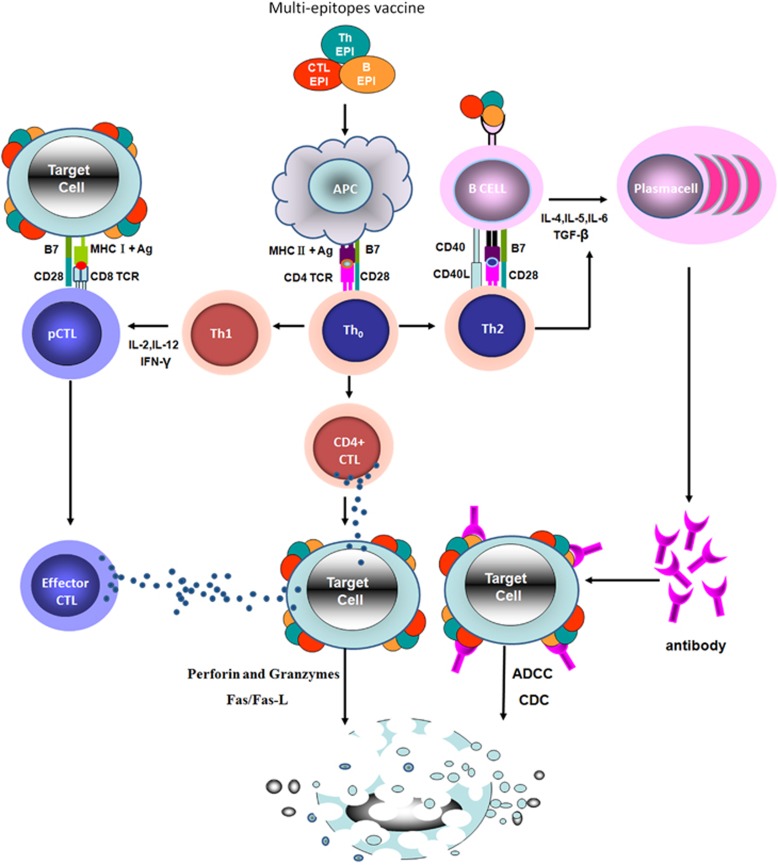

Immune responses play a critical role in fighting tumors and viral infections. An antigenic epitope is a basic unit that elicits either a cellular or a humoral immune response. A multi-epitope vaccine composed of a series of or overlapping peptides is therefore an ideal approach for the prevention and treatment of tumors or viral infections.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Although some multi-epitope vaccines have entered phase I clinical trials, for example, EMD640744 in patients with advanced solid tumors,6 designing efficacious multi-epitope vaccines remains a great challenge. An ideal multi-epitope vaccine should be designed to include epitopes that can elicit CTL, Th and B cells and induce effective responses against a targeted tumor or virus (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The molecular and cellular mechanism of immune responses induced by a multi-epitope vaccine. Multi-epitope vaccines can be composed of CTL, Th and B-cell epitopes in a series or overlapping epitope peptides. Through TCR, CD8+ precursor CTL (CD8+ pCTL) recognizes the complex of CTL antigen peptides bound to MHC class I molecules that are displayed by target cells (tumor cells or virus-infected cells). Antigen presenting cells (APC) take up the multi-epitope vaccine and present the Th antigen peptides bound to MHC class II molecules to Th0 cells. Th0 cells are differentiated into Th1, Th2 and CD4+ CTL cells. Th1 cells secrete cytokines that stimulate CD8+ pCTL to generate effector CTL cells, the latter of which will kill the target cells by both the perforin/granzyme and the Fas/FasL pathways. Th2 cells recognize the Th epitope bound to MHC class II molecules that are presented by B cells. After being activated, Th2 cells express CD40L molecules and secrete cytokines to stimulate B-cell activation; CD4+ CTL cells secrete cytotoxins, directly killing the target cells by releasing granules containing perforin and granzyme B. B cells recognize and take up the B epitopes of the multi-epitope vaccine by BCR, presenting the Th epitopes bound to MHC class II molecules to activate Th2 cells. The B cells then proliferate and differentiate into plasma cells after binding to the CD40L molecules and cytokines provided by activated Th2 cells. The plasma cells secrete multi-epitope vaccine-specific antibodies to perform anti-tumor or anti-virus tasks in target cells by antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) and complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC).

Compared to classical vaccines and single-epitope vaccines, multi-epitope vaccines have unique design concepts4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 with the following properties: (I) they consist of multiple MHC-restricted epitopes that can be recognized by TCRs of multiple clones from various T-cell subsets; (II) they consist of CTL, Th and B-cell epitopes that can induce strong cellular and humoral immune responses simultaneously; (III) they consist of multiple epitopes from different tumor or virus antigens that can expand the spectra of targeted tumors or viruses; (IV) they introduce some components with adjuvant capacity that can enhance the immunogenicity and long-lasting immune responses; and (V) they reduce unwanted components that can trigger either pathological immune responses or adverse effects. Well-designed multi-epitope vaccines with such advantages should become powerful prophylactic and therapeutic agents against tumors and viral infections.

Current problems in the field of multi-epitope vaccine design and development include the selection of appropriate candidate antigens and their immunodominant epitopes and the development of an effective delivery system. Development of a successful multi-epitope vaccine first depends on the selection of appropriate candidate antigens and their immunodominant epitopes. The prediction of appropriate antigenic epitopes of a target protein by immunoinformatic methods is extremely important for designing a multi-epitope vaccine.12, 13 In our laboratory, we always use immunoinformatic tools to predict and screen the immunogenic T- and B-cell epitopes of the target antigens, then design peptides rich in epitopes or overlapping epitopes.7, 8, 11, 14, 15 For the prediction of B-cell epitopes, multiple alignments of the target antigen are initially carried out using software from the European Bioinformatics Institute website (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/clustalw2). Then, the structure, hydrophilicity and flexibility, and transmembrane domains of the target antigen are predicted and analyzed by methods including GOR,16 Hoop and Woods17 and artificial neural network (http://strucbio.biologie.uni-konstanz.de). Antigenic propensity value is further evaluated using the Kolaskar and Tongaonkar approach (http://bio.dfci.harvard.edu/Tools/antigenic.pl). Finally, the B-cell-dominant epitope is determined by comprehensive analysis and comparison, and T-cell epitopes including MHC-I restriction CTL and MHC-restriction Th epitopes are predicted using the SYFPEITHI network database (http://www.syfpeithi.de/Scripts/MHCServer.dll/EpitopePrediction.htm). All the above-mentioned programs are provided on the EXPASY server (http://www.expasy.org/tools). Recently, we have developed a multi-epitope vaccine, named EBV LMP2m, which encodes multiple CTL, Th and B epitopes from the EBV LMP2 gene.11 Expression of the recombinant multi-epitope protein from the constructed multi-epitope vaccine gene was optimized to maximize its production in E. coli. The specific CTL and Th cell reactions and B-cell activation (serum-specific IgG and mucosal IgA antibodies) were analyzed in BALB/c mice immunized with the multi-epitope vaccine. The multi-epitope-specific serum antibodies in patients with EBV-related tumors (nasopharyngeal carcinoma) or EBV infection were analyzed using ELISA and western blotting. All the analyses demonstrated that the multi-epitope vaccine EBV LMP2m had a very high immunogenicity. Therefore, EBV LMP2m could be considered as a potential vaccine candidate and diagnostic agent.

The successful immunotherapy of a multi-epitope vaccine is also associated with an effective vaccine delivery system. At present, both virus-like particles (VLPs)7, 8, 14 and nanoparticles18, 19 have been used as vehicles for delivering multi-epitope vaccines. We have used two types of VLPs: hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg)-VLPs and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-VLPs. Our data have shown that either HBcAg or HBsAg-VLPs multi-epitope vaccines strongly elicit specifically humoral and cellular immune responses and generate vigorous immune responses of the individual epitopes carried by the multi-epitope vaccine.7, 8, 14

In summary, multi-epitope vaccines can be considered as a promising strategy against tumors and viral infections. Immunoinformatics methods can help to predict and screen appropriate epitopes for designing an efficacious multi-epitope vaccine. Both VLPs and nanoparticles used for delivering a multi-epitope vaccine could increase its immunogenicity.

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Buonaguro L. HEPAVAC consortium. Developments in cancer vaccines for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2016; 65: 93–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennick CA, George MM, Corwin WL, Srivastava PK, Ebrahimi-Nik H. Neoepitopes as cancer immunotherapy targets: key challenges and opportunities. Immunotherapy 2017; 9: 361–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo T, Wang C, Badakhshan T, Chilukuri S, BenMohamed L. The challenges and opportunities for the development of a T-cell epitope-based herpes simplex vaccine. Vaccine 2014; 32: 6733–6745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He R, Yang X, Liu C, Chen X, Wang L, Xiao M et al. Efficient control of chronic LCMV infection by a CD4 T cell epitope-based heterologous prime-boost vaccination in a murine model. Cell Mol Immunol 2017; e-pub ahead of print 13 March 2017; doi:10.1038/cmi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lu IN, Farinelle S, Sausy A, Muller CP. Identification of a CD4 T-cell epitope in the hemagglutinin stalk domain of pandemic H1N1 influenza virus and its antigen-driven TCR usage signature in BALB/c mice. Cell Mol Immunol 2017; 14: 511–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennerz V, Gross S, Gallerani E, Sessa C, Mach N, Boehm S et al. Immunologic response to the survivin-derived multi-epitope vaccine EMD640744 in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2014; 63: 381–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang P, Cai Y, Chen J, Ye X, Mao S, Zhu S et al. Evaluation of tamdem Chlamydia trachomatis MOMP multi-epitopes vaccine in BALB/c mice model. Vaccine 2017; 35: 3096–3103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S, Feng Y, Rao P, Xue X, Chen S, Li W et al. Hepatitis B virus surface antigen as delivery vector can enhance Chlamydia trachomatis MOMP multi-epitope immune response in mice. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2014; 98: 4107–4117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadi M, Karkhah A, Nouri HR. Development of a multi-epitope peptide vaccine inducing robust T cell responses against brucellosis using immunoinformatics based approaches. Infect Genet Evol 2017; 51: 227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Meng S, Jin Y, Zhang W, Li Z, Wang F et al. A novel multi-epitope vaccine from MMSA-1 and DKK1 for multiple myeloma immunotherapy. Br J Haematol 2017; 178: 413–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Chen S, Xue X, Lu L, Zhu S, Li W et al. Chimerically fused antigen rich of overlapped epitopes from latent membrane protein 2 (LMP2) of Epstein-Barr virus as a potential vaccine and diagnostic agent. Cell Mol Immunol 2016; 13: 492–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin D, Li L, Song X, Li H, Wang J, Ju W et al. A novel multi-epitope recombined protein for diagnosis of human brucellosis. BMC Infect Dis 2016; 16: 219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherryholmes GA, Stanton SE, Disis ML. Current methods of epitope identification for cancer vaccine design. Vaccine 2015; 33: 7408–7414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang P, Du W, Xiong Y, Lv Y, Feng J, Zhu S et al. Hepatitis B virus core antigen as a carrier for Chlamydia trachomatis MOMP multi-epitope peptide enhances protection against genital chlamydial infection. Oncotarget 2015; 6: 43281–43292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X, Jin J, Ding Y, Wang P, Wang A, Xiao D et al. Novel immunodominant epitopes derived from MAGE-A3 and its significance in serological diagnosis of gastric cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2013; 139: 1529–1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnier J, Gibrat JF, Robson B. GOR method for predicting protein secondary structure from amino acid sequence. Methods Enzymol 1996; 266: 540–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoop TP, Woods KR. Prediction of antigenic determinants from amino acid sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1981; 78: 3824–3828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuai R, Ochyl LJ, Bahjat KS, Schwendeman A, Moon JJ. Designer vaccine nanodiscs for personalized cancer immunotherapy. Nat Mater 2017; 16: 489–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alipour Talesh G, Ebrahimi Z, Badiee A, Mansourian M, Attar H, Arabi L et al. Poly (I:C)-DOTAP cationic nanoliposome containing multi-epitope HER2-derived peptide promotes vaccine-elicited anti-tumor immunity in a murine model. Immunol Lett 2016; 176: 57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]