Abstract

Objective(s):

Several lines of evidence showed that minocycline possesses antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. This study aimed to demonstrate the effects of minocycline in rats subjected to chronic constriction injury (CCI).

Materials and Methods:

In this study four groups (n = 6–8) of rats were used as follows: Sham, CCI, CCI + minocycline (MIN) 10 mg/Kg (IP) and CCI + MIN 30 mg/Kg (IP). On days 3, 7, 14, and 21 post-surgery hot-plate, acetone, and von Frey tests were carried out. Finally, Motor Nerve Conduction Velocity Evaluation (MNCV) assessment was performed and spinal cords were harvested in order to measure tissue concentrations of TNF_α, IL-1β, Glutathione peroxidase (GPx), Superoxide dismutase (SOD) and Malondialdehyde (MDA). Extent of perineural inflammation and damage around the sciatic nerve was histopathologically evaluated.

Results:

Our results demonstrated that CCI significantly caused hyperalgesia and allodynia twenty-one days after CCI. MIN attenuated heat hyperalgesia, cold and mechanical allodynia and MNCV in animals. MIN also decreased the levels of TNF_α and IL-1β. Antioxidative enzymes (SOD, MDA, and GPx) were restored following MIN treatment. Our findings showed that MIN decreased perineural inflammation around the sciatic nerve. According to the results, the neuropathic pain reduced in the CCI hyperalgesia model using 30 mg/kg of minocycline.

Conclusion:

It is suggested that antinociceptive effects of minocycline might be mediated through the inhibition of inflammatory response and attenuation of oxidative stress.

Keywords: Chronic constriction, Injury, Inflammatory response, Minocycline, Neuropathic pain, Oxidative stress, Rat

Introduction

Neuropathic pain (NP) is caused by several factors with impairment in nerve function. The pathophysiology of pain is relatively complex and involves the central and peripheral mechanisms. Alteration in the ion channel expression, neurotransmitter release, and pain pathways are involved in the pathophysiology of pain (1). NP consists of unpleasant sensations of burning, tingling, and increased sensitivity towards the hyperalgesia and allodynia (2). When the tissue is destroyed, an inflammatory reaction leads to the activation of the pain pathway (3).

It is known that both hyperalgesia and allodynia coexist in both, the inflammatory and neuropathic pain (4).

It has been well-documented that oxidative stress contributes to the pathophysiology of NP (5). In this regard, it is demonstrated that reduction in antioxidant protection, increase in oxidant generation, and loss of the capacity of repair from oxidative damage are involved in the NP consequence of oxidative stress (6).

Minocycline is a broad-spectrum and long-acting antibiotic and also possesses anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects (7, 8). It has been shown that minocycline acts as an inhibitor of microglial activation (9) and also exerts neuroprotective effects in the experimental model of brain ischemia (10, 11). Previous studies have demonstrated that systemic injection of minocycline reduces the microglia activation and consequently diminishes the production of the inflammatory cytokines in the CNS (12, 13). Ample evidence showed that minocycline protects neurons against impairment due to stroke and traumatic injury (14, 15). It is well-accepted that minocycline possesses antioxidant property (16, 17). Some researchers suggest that the neuroprotective effects of minocycline are via mitochondrial action. In this regard, minocycline executes its neuroprotective effect via inhibition (direct) of MPT (mitochondrial permeability transition) pores cytochrome c release (18, 19).

The aim of this study is to investigate the protective effect of different doses of minocycline on NP considering behavioral tests and antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties in a rat model of chronic constriction injury.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Thirty-two rats (male adult Sprague–Dawley) weighing 200–250 g were purchased and housed in standard conditions (4 rats per cage) i.e. temperature 23±2 °C, humidity of approximately 50%, and 12-hr light/dark cycle (9 a.m. - 9 p.m. lights on) (20). The animals had free availability of water and food.

Experimental design

Minocycline (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was suspended in distilled water. Pentobarbital sodium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used for anesthesia. Animals were divided randomly into four experimental groups (n= 8 rats per group): 1: Sham-operated (Sh), 2: CCI saline-treated (CCI), 3: CCI + Minocycline (MIN) 10 mg/kg intraperitoneal (IP), 4: CCI + MIN 30 mg/kg (IP). Minocycline was injected one day before surgery and continued daily for 21 days post-ligation. Doses of minocycline were chosen based on previously published study (21-23). Regarding these studies, we performed a pilot study and selected two doses of 10 and 30 mg/kg of minocycline.

Surgery

To induce sciatic nerve injury the CCI model of NP was performed (24). The surgical procedure was performed under pentobarbital Na (60 mg/kg) anesthesia. The left sciatic nerve was exposed and three ligations were put around the nerve. The space between two adjacent ligatures was 1 mm. In sham rats, the same surgical procedure was done, but not ligated.

Thermal stimulation tests

Behavioral tests were recorded on days 3, 7, 14, and 21 after ligation. The experiments were started with the heat hyperalgesia stimulation test and terminated with mechanical allodynia. 120 min was considered as the interval time between two tests.

Heat hyperalgesia stimulation (hot-plate test)

Eddy’s hot-plate, as an index of thermal hyperalgesia, was used to study the thermal nociceptive threshold by keeping the temperature at 52.5 ± 3.0 °C. Animals were placed on the hot-plate and withdrawal latency, with respect to the licking of the hind paw, was recorded in seconds. The cut-off time of 15 sec was maintained (25).

Cold allodynia (acetone test)

In cold allodynia test, the rat’s hind paw was placed over a wire mesh and 100 μl of acetone was sprayed onto its surface without touching the skin. The response to acetone was noted in 20 sec and was scored according to the criteria described by Kukkar and Singh as follows: 0: no reflex; 1: quick stamp, flick or withdrawal of the paw; 2: repeated flicking or prolonged withdrawal; and 3: repeated flicking with licking of the paw. In this test, acetone was used three times, every 5 min. The score range was defined from zero to nine (26).

Mechanical Allodynia (von Frey Test)

Briefly, the rats were placed in a cage (20 * 20 * 10 cm) whose floor was made of meshed metal wire. A chain of von Frey filament stimuli was delivered in an arising order of forces to the central section of the plantar hind paw skin (three times repeatedly). Stimulation of the plantar hind paw due to common locomotors behavior was ignored. The sequence of stimuli was stopped when the rat responded with immediate flinching or licking of the hind paw skin (27).

Motor Nerve Conduction Velocity Evaluation (MNCV)

MNCV recordings were carried out 3 weeks after CCI. On day 21, animals were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital Na (60 mg/kg, Sigma-Aldrich). To expose the sciatic nerve, the skin and muscles were disjointed layer by layer. MNCV was assessed by inducing a compound action potential from the stimulating electrode at the proximal end and recording from the recording electrode at the distal end of the injury site (28)

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA)

TNF_α, IL-1β, GPx, SOD, and MDA levels were assessed in the spinal cord samples. For this purpose, the spinal cord between the L4-L5 segments was isolated immediately after behavioral measurements. Homogenate tissues were prepared with 0.9% saline using glass homogenate and then centrifuged at 2500 r/min for 10 min. Supernatant (10%, w/v) was used for ELISA assay (29, 30).

Histologic evaluation

On day 21, sciatic nerves were dissected. Histological studies were performed according to the described protocol. For histological examination, samples of sciatic nerve were cut into segments of 5-micrometer sections and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. All samples were analyzed for perineural inflammation and according to protocol-defined guidelines (31).

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test using the Graph-pad prism software (ver. 6) was done for data analysis. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Minocycline decreased heat hyperalgesia

Results obtained from the hot-plate test (Figure 1) showed that CCI significantly decreased the pain threshold in days 3, 7, 14, and 21 (P<0.001, for all days) after the operation. Following treatment with minocycline 10 mg/kg pain threshold significantly increased when compared with the CCI group in days 14 (P<0.05) and 21 (P<0.01) post-surgery. Our findings from administration of minocycline 30 mg/kg showed that pain sensitivity decreased in days 3 (P<0.05), 7 (P<0.01), 14 (P<0.001), and 21 (P<0.001) post operation in comparison with CCI counterparts. Furthermore, minocycline at dose 30 mg/kg in days 7 and 14 post induction of NP decreased sensitivity in comparison with minocycline 10 mg/kg (P<0.05).

Figure 1.

The effect of minocycline administration on CCI-induced heat hyperalgesia, assessed using the hot-plate test. Rats were treated with vehicle or minocycline at doses of 10 and 30 mg/kg once daily for a period of 21 days. The data were shown as mean ± SEM. ** P< 0.01 vs Sham, ***P< 0.001 vs Sham, #P< 0.05 vs CCI, ## P< 0.01 vs CCI, and ### P< 0.001 vs CCI

Minocycline decreased cold allodynia scores

Results obtained from acetone test (Figure 2) revealed that induction of CCI significantly increased allodynia scores in days 3 (P<0.05), 7, 14, and 21 after surgery in comparison with sham groups (P<0.001). Post hoc analysis showed that administration of minocycline (10 and 30 mg/kg) significantly reduced allodynia scores when compared with CCI counterparts in days 7 (P<0.05), 14 and 21 post operation (P<0.001).

Figure 2.

The effects of minocycline administration on CCI- induced cold allodynia assessed using the acetone test. Rats were treated with vehicle or minocycline at doses of 10 and 30 mg/kg once daily for a period of 21 days. The data were shown as mean ± SEM. *** P< 0.001 vs Sham, # P< 0.05 vs CCI, and ### P< 0.001 vs CCI

Minocycline increased latency to mechanical allodynia

Our results from von ferry test (Figure 3) demonstrated that CCI operation significantly increased sensitivity to mechanical allodynia in days 7 (P>0.05), 14 (P>0.001), and 21 (P>0.001) post induction when compared with related sham counterparts. Administration of minocycline at a dose of 30 mg/kg increased latency to mechanical stimulation at day 21 post-CCI operation in comparison with CCI groups (P<0.05).

Figure 3.

The effects of minocycline administration on CCI-induced mechanical allodynia assessed using the von Frey test. Rats were treated with vehicle or minocycline at doses of 10 and 30 mg/kg once daily for a period of 21 days. The data were shown as mean ± SEM. ** P< 0.01 vs Sham, *** P< 0.001 vs Sham, and ### P< 0.001 vs CCI

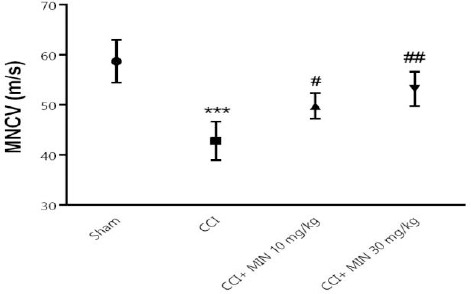

Effect of minocycline on MNCV

Neural conduction was reduced in the CCI group relative to the sham group at the 21st day after injury (P<0.01), indicating that neural conduction was diminished (Figure 4). MNCV values began to recover by 3 weeks in 10 mg/kg and 30 mg/kg of minocycline treatment groups (P< 0.05, P< 0.1, respectively).

Figure 4.

The effects of minocycline administration on MNCV in the sciatic nerve. Rats were treated with vehicle or minocycline at doses of 10 and 30 mg/kg once daily for a period of 21 days. The data were shown as mean ± SEM; *** P< 0.001 vs Sham, # P< 0.05 vs CCI, and ### P< 0.001 vs CCI

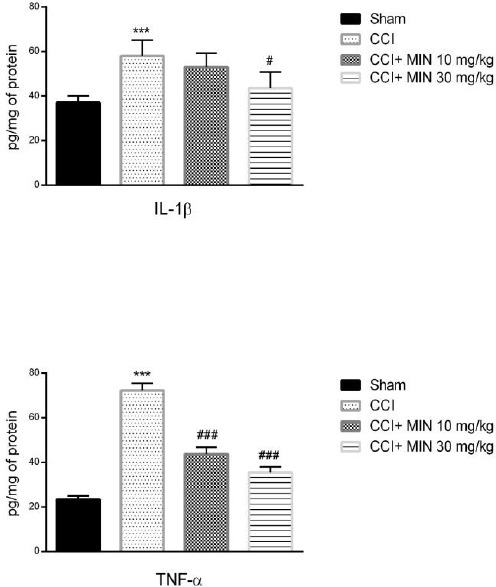

Minocycline decreased levels of inflammatory cytokines

Our findings revealed that levels of TNF-α and IL-1β significantly increased in the 21st day post-surgery in comparison with their sham counterparts (P<0.001 for both). Moreover, treatment with dose 30 mg/kg of minocycline decreased the concentration of IL-1β when compared with the CCI group (P<0.05). Furthermore, minocycline at doses 10 and 30 mg/kg significantly decreased the level of TNF-α in comparison with the CCI group (P<0.001 for both) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The effects of minocycline administration on IL-1β and TNF-α in the spinal nerve. Rats were treated with vehicle or minocycline at doses of 10 and 30 mg/kg once daily for a period of 21 days. The data were shown as mean ± SEM; *** P< 0.001 vs Sham, # P< 0.05 vs CCI, and ### P< 0.001 vs CCI

Effect of minocycline on oxidative markers

Measurement of concentration of markers relevant to the oxidative/anti-oxidative state using ELISA (Figure 6) showed that CCI led to increase in the level of MDA and decrease in the levels of SOD as well as GPx (P<0.001 for both). Minocycline (10 and 30 mg/kg) significantly decreased the levels of MDA (P<0.001 for both), increased the levels of SOD (P<0.05 and P<0.01, respectively), and glutamine peroxidase (P<0.001 for both) compared to the CCI group.

Figure 6.

The effects of minocycline administration on MDA, SOD, and GPx levels in the spinal nerve. Rats were treated with vehicle or minocycline at doses of 10 and 30 mg/kg once daily for a period of 21 days. The data were shown as mean ± SEM, *** P< 0.001 vs Sham, # P< 0.05 vs CCI, ## P< 0.01 vs CCI, and ### P< 0.001 vs CCI

Minocycline decreased perineural inflammation around the sciatic nerve

Figure 7 shows that there are normal structural in the sciatic nerve of sham animals. Moreover, histological results from CCI groups showed that there was extensive perineural inflammation around the sciatic nerve (score=3). However, administration of minocycline (30 mg/kg) attenuated CCI induced inflammation ratio around the sciatic nerve (score = 1). Furthermore, nerve injury was not detected in the sciatic nerve of any group (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Histological and morphological studies in the sciatic nerve at 21 days after CCI induction. In untreated CCI rats, the sciatic nerve has diffuse areas of moderate to marked edema/cellular infiltrate. In the MIN-treated (30 mg/kg) CCI rats, the finding is small focal areas of mild edema and/or cellular infiltrate

Discussion

CCI model is a valid model used to induce NP (32). In this study, we demonstrated that chronic constriction injury induced NP within twenty-one days after the operation. Our results showed that treatment with minocycline (10 and 30 mg/kg) for a 21 day period significantly improved the behavioral changes induced by CCI, including heat hyperalgesia, cold and mechanical allodynia, and MNCV. Furthermore, minocycline attenuated inflammatory cytokines as well as oxidative stress markers. Also, we observed that administration of minocycline significantly decreased perineural inflammation around the sciatic nerve. Our findings demonstrated that optimum result were obtained from 30 mg/kg of minocycline.

It has been determined that minocycline exerted antioxidant effects and mitigated the glial cells damage due to oxidative/nitrosative stress (33, 34). Conversely, in another study, it was found that minocycline possessed some beneficial effects on the oxidative stress in diabetic animals (35). The anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties of minocycline have been studied. In this regards, it is determined that minocycline is effective in Parkinson’s disease (36), Alzheimer’s disease (37), and also in a genetic mouse model of retinitis pigmentosa (38). El-Shimy et al. showed that minocycline reduced the inflammatory response and exerted protective effects in nerve cells against nerve toxins (39).

Minocycline reduced the activity of the MAPK pathway in microglia (40). It is found that minocycline acted as an anti-apoptotic agent (41) and protected neurons from caspase activation through decreased Ca+ absorption and decreasing the release of cytochrome-C from mitochondria (42). Previous studies declared that minocycline indirectly regulated the increase of the anti-apoptotic factors, e.g. BCL2 (43) and also inhibited the apoptosis proteins (44). Minocycline inhibits the activation of microglia and reduces the expression of the inflammatory mediators (45). It has been shown that minocycline is effective in chronic disorders caused by diabetes, and three week treatment with minocycline improved the diabetic neuropathy (46). It is important to state that long-term treatment with minocycline is completely safe (47). Compared with normal rats and sciatic nerve injury rats, TNF-α upregulation was in nerve cells and detectable at the damage site in the standard model of NP (48). It has been shown that the levels of TNF-α increased in the locus coeruleus and hippocampus (49). Upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1Β, has been reported in the spinal cord and ipsilateral ganglia following nerve injury (50). In addition, it was reported that in the animal models of NP, the receptors of IL-1β have been induced by TNF-α receptor 1 (51). In the present study, minocycline reduced the levels of TNF-α and IL-1β, which may have partial roles in the efficacy of this agent in prevention of NP. Elevated levels of ROS induce persistent pain and related pain behaviors and also, it has been detected in ipsilateral superficial laminae (I-III) of the spinal cord (52). Preclinical evidence supports the fact that oxidative stress could enhance NP and induced hyperalgesia in the injured peripheral nerve and/or spinal cord (53). Our findings suggest that minocycline could be at least in part through the modulation of oxidative stress mitigated NP in the CCI model.

Conclusion

The present findings support that minocycline possessed anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects in the chronic constriction injury induced NP and could prevent and at least delay the development of hypersensitivity in the CCI model.

Acknowledgment

This work was conducted with the support of Lorestan University of Medical Sciences (grant no. A-10-1758-3).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Zhuo M. Neuronal mechanism for neuropathic pain. Mol Pain. 2007;3:14. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dworkin RH, Backonja M, Rowbotham MC, Allen RR, Argoff CR, Bennett GJ, et al. Advances in neuropathic pain: diagnosis, mechanisms, and treatment recommendations. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1524–1534. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.11.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Jongh RF, Vissers KC, Meert TF, Booij LH, De Deyne CS, Heylen RJ. The role of interleukin-6 in nociception and pain. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:1096–1103. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000055362.56604.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saika F, Kiguchi N, Kobayashi Y, Kishioka S. Peripheral alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor signalling attenuates tactile allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia after nerve injury in mice. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2015;213:462–471. doi: 10.1111/apha.12437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma W, Quirion R. Does COX2-dependent PGE2 play a role in neuropathic pain?Neurosci Lett. 2008;437:165–169. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.02.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naik AK, Tandan SK, Dudhgaonkar SP, Jadhav SH, Kataria M, Prakash VR, et al. Role of oxidative stress in pathophysiology of peripheral neuropathy and modulation by N-acetyl-L-cysteine in rats. Eur J Pain. 2006;10:573–579. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kielian T, Esen N, Liu S, Phulwani NK, Syed MM, Phillips N, et al. Minocycline modulates neuroinflammation independently of its antimicrobial activity in staphylococcus aureus-induced brain abscess. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:1199–1214. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kraus RL, Pasieczny R, Lariosa-Willingham K, Turner MS, Jiang A, Trauger JW. Antioxidant properties of minocycline: neuroprotection in an oxidative stress assay and direct radical-scavenging activity. J Neurochem. 2005;94:819–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tikka TM, Koistinaho JE. Minocycline provides neuroprotection against N-methyl-D-aspartate neurotoxicity by inhibiting microglia. J Immunol. 2001;166:7527–7533. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yrjanheikki J, Tikka T, Keinanen R, Goldsteins G, Chan PH, Koistinaho J. A tetracycline derivative, minocycline, reduces inflammation and protects against focal cerebral ischemia with a wide therapeutic window. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13496–13500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mishra MK, Ghosh D, Duseja R, Basu A. Antioxidant potential of Minocycline in Japanese Encephalitis Virus infection in murine neuroblastoma cells: correlation with membrane fluidity and cell death. Neurochem Int. 2009;54:464–470. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan LW, Pang Y, Lin S, Tien LT, Ma T, Rhodes PG, et al. Minocycline reduces lipopolysaccharide-induced neurological dysfunction and brain injury in the neonatal rat. J Neurosci Res. 2005;82:71–82. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henry CJ, Huang Y, Wynne A, Hanke M, Himler J, Bailey MT, et al. Minocycline attenuates lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced neuroinflammation, sickness behavior, and anhedonia. J Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:15. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heo K, Cho YJ, Cho KJ, Kim HW, Kim HJ, Shin HY, et al. Minocycline inhibits caspase-dependent and -independent cell death pathways and is neuroprotective against hippocampal damage after treatment with kainic acid in mice. Neurosci Lett. 2006;398:195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stirling DP, Koochesfahani KM, Steeves JD, Tetzlaff W. Minocycline as a neuroprotective agent. Neuroscientist. 2005;11:308–322. doi: 10.1177/1073858405275175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shahzad K, Bock F, Al-Dabet MM, Gadi I, Nazir S, Wang H, et al. Stabilization of endogenous Nrf2 by minocycline protects against Nlrp3-inflammasome induced diabetic nephropathy. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34228. doi: 10.1038/srep34228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen W, Zhao M, Zhao S, Lu Q, Ni L, Zou C, et al. Activation of the TXNIP/NLRP3 inflammasome pathway contributes to inflammation in diabetic retinopathy: a novel inhibitory effect of minocycline. Inflamm Res. 2017;66:157–166. doi: 10.1007/s00011-016-1002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teng YD, Choi H, Onario RC, Zhu S, Desilets FC, Lan S, et al. Minocycline inhibits contusion-triggered mitochondrial cytochrome c release and mitigates functional deficits after spinal cord injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3071–3076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306239101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Zhu S, Drozda M, Zhang W, Stavrovskaya IG, Cattaneo E, et al. Minocycline inhibits caspase-independent and -dependent mitochondrial cell death pathways in models of Huntington's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10483–10487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1832501100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baumans V, Van Loo PL. How to improve housing conditions of laboratory animals: the possibilities of environmental refinement. Vet J. 2013;195:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2012.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamidi GA, Jafari-Sabet M, Abed A, Mesdaghinia A, Mahlooji M, Banafshe HR. Gabapentin enhances anti-nociceptive effects of morphine on heat, cold, and mechanical hyperalgesia in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2014;17:753–759. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hajhashemi V, Minaiyan M, Banafshe HR, Mesdaghinia A, Abed A. The anti-inflammatory effects of venlafaxine in the rat model of carrageenan-induced paw edema. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2015;18:654–658. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Padi SS, Kulkarni SK. Minocycline prevents the development of neuropathic pain, but not acute pain: possible anti-inflammatory and antioxidant mechanisms. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;601:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bennett GJ, Xie YK. A peripheral mononeuropathy in rat that produces disorders of pain sensation like those seen in man. Pain. 1988;33:87–107. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jain V, Jaggi AS, Singh N. Ameliorative potential of rosiglitazone in tibial and sural nerve transection-induced painful neuropathy in rats. Pharmacol Res. 2009;59:385–392. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kukkar A, Singh N, Jaggi AS. Neuropathic pain-attenuating potential of aliskiren in chronic constriction injury model in rats. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2013;14:116–123. doi: 10.1177/1470320312460899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abed A, Hajhashemi V, Banafshe HR, Minaiyan M, Mesdaghinia A. Venlafaxine Attenuates Heat Hyperalgesia Independent of Adenosine or Opioid System in a Rat Model of Peripheral Neuropathy. Iran J Pharm Res. 2015;14:843–850. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang H, Li X, Shan L, Zhu J, Chen R, Li Y, et al. Recombinant hNeuritin Promotes Structural and Functional Recovery of Sciatic Nerve Injury in Rats. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:589. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saeedi Saravi SS, Hasanvand A, Shahkarami K, Dehpour AR. The protective potential of metformin against acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in BALB/C mice. Pharm Biol. 2016;54:2830–2837. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2016.1185633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hasanvand A, Abbaszadeh A, Darabi S, Nazari A, Gholami M, Kharazmkia A. Evaluation of selenium on kidney function following ischemic injury in rats;protective effects and antioxidant activity. J Renal Inj Prev. 2016;6:93–98. doi: 10.15171/jrip.2017.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brummett CM, Padda AK, Amodeo FS, Welch KB, Lydic R. Perineural dexmedetomidine added to ropivacaine causes a dose-dependent increase in the duration of thermal antinociception in sciatic nerve block in rat. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:1111–1119. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181bbcc26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jaggi AS, Jain V, Singh N. Animal models of neuropathic pain. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2011;25:1–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2009.00801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yenari MA, Xu L, Tang XN, Qiao Y, Giffard RG. Microglia potentiate damage to blood-brain barrier constituents: improvement by minocycline in vivo and in vitro. Stroke. 2006;37:1087–1093. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000206281.77178.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whiteman M, Halliwell B. Prevention of peroxynitrite-dependent tyrosine nitration and inactivation of alpha1-antiproteinase by antibiotics. Free Radic Res. 1997;26:49–56. doi: 10.3109/10715769709097783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pabreja K, Dua K, Sharma S, Padi SS, Kulkarni SK. Minocycline attenuates the development of diabetic neuropathic pain: possible anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant mechanisms. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;661:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Biscaro B, Lindvall O, Tesco G, Ekdahl CT, Nitsch RM. Inhibition of microglial activation protects hippocampal neurogenesis and improves cognitive deficits in a transgenic mouse model for Alzheimer's disease. Neurodegener Dis. 2012;9:187–198. doi: 10.1159/000330363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu DC, Jackson-Lewis V, Vila M, Tieu K, Teismann P, Vadseth C, et al. Blockade of microglial activation is neuroprotective in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine mouse model of Parkinson disease. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1763–1771. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01763.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peng B, Xiao J, Wang K, So KF, Tipoe GL, Lin B. Suppression of microglial activation is neuroprotective in a mouse model of human retinitis pigmentosa. J Neurosci. 2014;34:8139–8150. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5200-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.El-Shimy IA, Heikal OA, Hamdi N. Minocycline attenuates Abeta oligomers-induced pro-inflammatory phenotype in primary microglia while enhancing Abeta fibrils phagocytosis. Neurosci Lett. 2015;609:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nikodemova M, Duncan ID, Watters JJ. Minocycline exerts inhibitory effects on multiple mitogen-activated protein kinases and IkappaBalpha degradation in a stimulus-specific manner in microglia. J Neurochem. 2006;96:314–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi Y, Kim HS, Shin KY, Kim EM, Kim M, Kim HS, et al. Minocycline attenuates neuronal cell death and improves cognitive impairment in Alzheimer's disease models. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:2393–2404. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu S, Stavrovskaya IG, Drozda M, Kim BY, Ona V, Li M, et al. Minocycline inhibits cytochrome c release and delays progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in mice. Nature. 2002;417:74–78. doi: 10.1038/417074a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang J, Wei Q, Wang CY, Hill WD, Hess DC, Dong Z. Minocycline up-regulates Bcl-2 and protects against cell death in mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19948–19954. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313629200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scarabelli TM, Stephanou A, Pasini E, Gitti G, Townsend P, Lawrence K, et al. Minocycline inhibits caspase activation and reactivation, increases the ratio of XIAP to smac/DIABLO, and reduces the mitochondrial leakage of cytochrome C and smac/DIABLO. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:865–874. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu F, Zheng Y, Liu Y, Zhang X, Zhao J. Minocycline alleviates behavioral deficits and inhibits microglial activation in the offspring of pregnant mice after administration of polyriboinosinic-polyribocytidilic acid. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219:680–686. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cukras CA, Petrou P, Chew EY, Meyerle CB, Wong WT. Oral minocycline for the treatment of diabetic macular edema (DME): results of a phase I/II clinical study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:3865–3874. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-9413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bhatt LK, Veeranjaneyulu A. Minocycline with aspirin: a therapeutic approach in the treatment of diabetic neuropathy. Neurol Sci. 2010;31:705–716. doi: 10.1007/s10072-010-0243-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shubayev VI, Myers RR. Upregulation and interaction of TNFalpha and gelatinases A and B in painful peripheral nerve injury. Brain Res. 2000;855:83–89. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Covey WC, Ignatowski TA, Knight PR, Spengler RN. Brain-derived TNFalpha: involvement in neuroplastic changes implicated in the conscious perception of persistent pain. Brain Res. 2000;859:113–122. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)01965-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee H-L, Lee K-M, Son S-J, Hwang S-H, Cho H-J. Temporal expression of cytokines and their receptors mRNAs in a neuropathic pain model. Neuroreport. 2004;15:2807–2811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee KM, Jeon SM, Cho HJ. Tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 induces interleukin-6 upregulation through NF-kappaB in a rat neuropathic pain model. Eur J Pain. 2009;13:794–806. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Siniscalco D, Fuccio C, Giordano C, Ferraraccio F, Palazzo E, Luongo L, et al. Role of reactive oxygen species and spinal cord apoptotic genes in the development of neuropathic pain. Pharmacol Re. 2007;55:158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim HY, Wang J, Lu Y, Chung JM, Chung K. Superoxide signaling in pain is independent of nitric oxide signaling. Neuroreport. 2009;20:1424–1428. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328330f68b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]