Abstract

We use polygenic risk scores (PRSs) for schizophrenia (SCZ) and bipolar disorder (BPD) to predict smoking, and addiction to nicotine, alcohol or drugs in individuals not diagnosed with psychotic disorders. Using PRSs for 144 609 subjects, including 10 036 individuals admitted for in‐patient addiction treatment and 35 754 smokers, we find that diagnoses of various substance use disorders and smoking associate strongly with PRSs for SCZ (P = 5.3 × 10−50–1.4 × 10−6) and BPD (P = 1.7 × 10−9–1.9 × 10−3), showing shared genetic etiology between psychosis and addiction. Using standardized scores for SCZ and BPD scaled to a unit increase doubling the risk of the corresponding disorder, the odds ratios for alcohol and substance use disorders range from 1.19 to 1.31 for the SCZ‐PRS, and from 1.07 to 1.29 for the BPD‐PRS. Furthermore, we show that as regular smoking becomes more stigmatized and less prevalent, these biological risk factors gain importance as determinants of the behavior.

Keywords: polygenic scores, psychotic disorders, substance abuse

Introduction

Addiction to tobacco, alcohol or drugs is frequently a co‐morbidity of other psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia (SCZ) and bipolar disorder (BPD) (Cerullo & Strakowski 2007; Margolese et al. 2004). The high rate of smoking among SCZ patients is well known, and increased rates of substance use disorders and smoking are observed among their first‐degree relatives (Smith et al. 2008). The situation is similar for BPD, with over 40 percent co‐morbidity of substance use disorders (Cerullo & Strakowski 2007) and high smoking rates as well (Jackson et al. 2015). These high co‐morbidities call for an explanation, but separating cause and consequence has remained a challenge, the case of cannabis use and the onset of psychosis being a pertinent example (Marconi et al. 2016). Substance use can be a consequence of underlying psychiatric disorders, i.e. represent a form of self‐medication (Khantzian 1985), thereby increasing risk of addiction. Alternatively, substance use, particularly excessive use, may increase the risk of later developing various psychiatric disorders (Kenneson, Funderburk & Maisto 2013). Both SCZ and BPD have a prevalence of about 1 percent and are associated with premature mortality and low quality of life (McGrath et al. 2008; Blanco et al. 2016). Dual diagnoses of psychosis and a substance use disorder are associated with severity and chronicity of both conditions (Hartz et al. 2014). It is of great public health importance to understand these relationships, as smoking and substance use have consequences that greatly influence health and life expectancy of individuals with mental disorders (Osborn et al. 2007). In 2012, 3.3 million deaths, or nearly six percent of all global deaths, were attributable to alcohol consumption (http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/global_alcohol_report/en/), and tobacco smoking is a major cause of preventable deaths, claiming approximately six million victims per year (http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2015/en/).

Addictions to alcohol, nicotine and illicit drugs are heritable disorders influenced by many variants of small effect (Goldman, Oroszi & Ducci 2005; Manolio et al. 2009), as are SCZ and BPD (PGC‐Bipolar‐Disorder‐Working‐Group 2011; PGC‐Schizophrenia‐Working‐Group 2014). Using polygenic risk scores (PRSs) from an ensemble of common sequence variants of small effects can aid in elucidating whether co‐morbidity relationships reflect shared genetics. In particular, the PRS methodology can be applied to subjects who do not have the psychiatric disorders, providing separation of the effect of the diseases themselves from those of the underlying genetic risk factors. PRSs and LD score regression (Bulik‐Sullivan et al. 2015b) have revealed shared genetic etiology between SCZ and BPD (Bulik‐Sullivan et al. 2015a), between psychosis and cannabis use (Power et al. 2014), and use of other substances (Bulik‐Sullivan et al. 2015a). Given these relationships, we hypothesized that the SCZ‐ and BPD‐PRSs could be used to reveal the extent of genetic overlap between these psychotic disorders and substance use disorders.

Methods

Subjects

This study involved 144 609 Icelandic subjects. The age and sex distributions are provided in Table 1. The study was approved by the Icelandic Data Protection Authority and the National Bioethics Committee. All participating subjects who donated blood also signed informed consent. Personal identities of the patients and biological samples were encrypted by a third‐party system provided by the Icelandic Data Protection Authority. Controls were recruited as a part of various genetic research programs at deCODE and were not specifically screened for psychiatric disorders or substance use disorders. Individuals diagnosed with SCZ or BPD were excluded from controls.

Table 1.

Number of cases and demographic data.

| Phenotype | n (% women) | Mean age (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| PRS phenotypes | ||

| SCZ | 600 (35.7) | 61.31 (16.77) |

| BPD | 772 (63.3) | 69.88 (18.67) |

| Smoking | ||

| FTND | 4609 (52.5) | 57.26 (12.07) |

| FTND wo. adm. | 2940 (63.5) | 57.21 (11.16) |

| CPD | 35 754 (61.8) | 65.75 (16.82) |

| CPD wo. adm. | 31 511 (64.8) | 66.38 (16.96) |

| Ever‐smoking versus never‐smokinga | 35 567 (61.6) | 65.79 (16.83) |

| Ever‐smoking versus never‐smoking wo. adm.a | 31 330 (64.6) | 66.42 (16.97) |

| Substance use disorders | ||

| Alcohol use disorder | 8701 (32.7) | 55.74 (15.45) |

| Amphetamine use disorder | 1744 (33.5) | 41.17 (11.52) |

| Cocaine use disorder | 645 (28.5) | 38.84 (10.25) |

| Cannabis use disorder | 1896 (29.7) | 40.34 (11.76) |

| Opioid use disorder | 501 (49.1) | 51.13 (13.12) |

| Sedative use disorder | 1625 (51.8) | 54.91 (14.89) |

| EO | 2810 (34.7) | 39.56 (10.13) |

| Number of admissions | 10 036 (32.5) | 56.87 (16.47) |

| Total sample | 144 609 (53.7) | 56.60 (20.90) |

BPD, bipolar disorder; CPD, cigarettes per day; EO, early onset of alcohol and/or substance use disorder; FTND, Fagerström Test of nicotine dependence; PRS, polygenic risk scores; SCZ, schizophrenia; wo. adm., without admission to the addiction treatment program.

For ever‐smoking versus never‐smoking, the number of ever‐smokers is listed, and the control group consisted of 17 145 never smokers.

Smoking phenotypes

The Fagerström Test for nicotine dependence (FTND) (Heatherton et al. 1991) is a standard questionnaire designed to assess the intensity of physical addiction to nicotine. FTND data were obtained from questionnaires answered by participants in deCODE's study of nicotine dependence (ND) (2004–2014)(Thorgeirsson et al. 2008). Responses to FTND questions generate a score of 0–10, with higher scores representing greater ND (Heatherton et al. 1991). Information on smoking quantity (SQ) was also utilized, but SQ was available from a standardized smoking questionnaire used in deCODE's studies that asks: ‘How many cigarettes per day do/did you smoke on average (on most days)?’ This means that current smokers answer about their current consumption and former smokers refer to their consumption in the past. In cases where multiple records were available, we recorded the maximum reported cigarettes per day (CPD). Never smokers were excluded from studies of CPD. The SQ was categorized into four levels, (1–10, 11–20, 21–30 and 31+ CPD). Information on ever‐smoking versus never‐smoking was obtained from questionnaires, typically asking about regular daily smoking for an extended period of time, most often 1 year. Subjects with SCZ or BPD diagnoses were excluded from smoking samples (Table 1).

Substance use disorders

Subjects were recruited through the largest addiction treatment center in Iceland, the SAA‐National Center of Addiction Medicine (Tyrfingsson et al. 2010). All patients were admitted for an in‐patient detoxification treatment and rehabilitation program. Substance use disorder diagnoses were made by clinicians using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) system. The diagnoses were made between the years 1977 and 2014, most using DSM‐IIIR and DSM‐IV. This is a treatment sample, and most of the patients have severe substance use disorders, scoring well above the thresholds for diagnosis of substance dependence in DSM‐IIIR and DSM‐IV. Co‐morbidity is high (Tyrfingsson et al. 2010), and patients diagnosed with more than one substance use disorders were included. The substances considered in this study were as follows: alcohol, amphetamine, cannabis, cocaine, opioids and sedatives (Table 1). Subjects diagnosed with SCZ or BPD were excluded.

Psychiatric disorders

The Icelandic SCZ sample consisted of 600 cases. Diagnoses were assigned according to research diagnostic criteria (Spitzer, Endicott & Robins 1978) through the use of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia Lifetime Version. Subjects diagnosed with BPD were excluded (Table 1). The Icelandic BPD sample consisted of 772 cases. Diagnoses were assigned according to Research Diagnostic Criteria, DSM‐IV, ICD‐9 or −10 and DSM‐III. Cases diagnosed with SCZ were excluded (Table 1).

Genotyping and imputation

Genotyping was carried out using Illumina chips. Quality control, long‐range phasing and imputation were carried out as previously described (Gudbjartsson et al. 2015).

Statistical analysis

Polygenic risk scores for SCZ and BPD were tested for association with SCZ and BPD in Iceland, and both PRSs also tested for association with smoking, ND, alcohol dependence and substance use disorders. Individuals diagnosed with SCZ or BPD were excluded from the analyses for ND, alcohol dependence and substance use disorder. Association to case–control and quantitative trait phenotypes were computed using logistic and linear regression, respectively. For each case–control phenotype studied, the remainder of the sample was used as controls. All models were adjusted for sex, year of birth and place of birth. Interaction between sex and PRS was tested by including a sex × PRS term in the regression models. If the interaction term was significant (P < 0.05), the sample was stratified by sex and tested for association with the PRS, without sex as a covariate. Interaction between PRS and year of birth was similarly tested by including a PRS × year of birth term in the regression models. Subjects within the CPD and ever‐smoking versus never‐smoking phenotypes were additionally stratified by decade of birth to determine the contribution of SCZ genetic risk to smoking/ND as smoking rates change in the general population. The variance explained (R 2) by polygenic scores was computed using Nagelkerke's pseudo‐R 2 for case–control phenotypes. The R 2 of the model including only covariates was subtracted from the R 2 of the full model (polygenic scores and covariates). For quantitative‐trait phenotypes, R 2 was computed using the deviance of the full model divided by the deviance of the model including only covariates. Effects and odds ratios (ORs) are reported for one unit change in polygenic score. To account for inflation due to relatedness and population stratification, the test statistics for each analysis was divided by an inflation factor estimated from LD score regression (Bulik‐Sullivan et al. 2015b).

Polygenic risk scores

Polygenic risk scores were obtained using P‐values and log OR from a subset of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) included in genome‐wide association studies (GWASs) of the Psychiatric Genetics Consortium (PGC‐Bipolar‐Disorder‐Working‐Group 2011; PGC‐Schizophrenia‐Working‐Group 2014). The subsets were prepared by the SCZ and BPD working groups using P‐value informed clumping. Neither of the GWAS included Icelandic data. The SCZ and BPD subsets contained 102 636 and 108 834 SNPs, respectively. Selecting SNPs in the Icelandic data with minor allele frequency ≥0.01, imputation info ≥0.8 and excluding G/C and A/T SNPs, 84 204 and 72 457 SNPs of the SCZ and BPD subsets, respectively, matched the Icelandic data. The SCZ‐PRS was computed from the 2014 meta‐analysis of the schizophrenia working group of the PGC (36 989 cases and 113 075 controls) (https://www.med.unc.edu/pgc/files/resultfiles/scz2.prs.txt.gz), and the BPD‐PRS was computed from the 2011 meta‐analysis of the BPD working group (7481 cases and 9250 controls), i.e. pgc.bip.clump.2012–04.txt from (https://www.med.unc.edu/pgc/files/resultfiles/pgc.bip.2012‐04.zip). Polygenic scores were computed at 500 equally spaced P‐value thresholds in the range 0.001–0.5. The association between the PRS and its corresponding disorder within the Icelandic population was tested for each P‐value threshold using logistic regression, including sex, age and place of birth as covariates (Supporting Information Fig. S3). The strongest association and the highest explained variance were obtained at P‐value threshold of 0.118 for SCZ‐PRS and 0.190 for BPD‐PRS. The SCZ‐PRS explained 4.67 percent of the variance in schizophrenia (P = 1.4 × 10−67), and the BPD‐PRS explained 0.90 percent of the variance in BPD (P = 1.3 × 10−18). The SCZ‐PRS and BPD‐PRS at these P‐value thresholds have a moderate degree of correlation, with an R 2 of 4.38 percent. The SCZ‐PRS and BPD‐PRS were centered by subtracting the mean and multiplied by 0.3399 and 0.0827, respectively, such that one unit increase in PRS results in an OR of 2 for their corresponding disorder in Iceland. The distribution of the PRSs before and after scaling is shown in the Supporting Information Fig. S2. Note that the SCZ‐PRS has a broader distribution than the BPD‐PRS; therefore, of the controls, 18 percent have a SCZ‐PRS above 1 while 1.8 percent have a BPD‐PRS above 1.

Results

In this study, we used a sample of 144 609 Icelandic individuals to estimate for smoking and substance use disorders the genetics shared with SCZ and BPD (Table 1). We computed PRSs using summary data from the meta‐analyses of the schizophrenia and BPD working groups of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, neither of which included Icelandic data (PGC‐Bipolar‐Disorder‐Working‐Group 2011; PGC‐Schizophrenia‐Working‐Group 2014) (Methods and Supporting Information).

The SCZ‐PRS and BPD‐PRS explained 4.67 percent and 0.90 percent of the risk variance in their corresponding disorders in Iceland (Table 2). For subsequent analyses, we scaled the PRSs such that each unit increase doubles the risk of the corresponding disorder (Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations between polygenic scores and phenotypes.

| SCZ‐PRS | BPD‐PRS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case/control | OR (95% CI) | R 2 [%] | P | OR (95% CI) | R 2 [%] | P |

| SCZ | 2.00 (1.85–2.16) | 4.67 | 1.4 × 10−67 | 1.73 (1.44–2.08) | 0.53 | 4.4 × 10−9 |

| BPD | 1.35 (1.26–1.44) | 0.92 | 4.8 × 10−19 | 2.00 (1.71–2.33) | 0.90 | 1.3× 10−18 |

| Alcohol UD | 1.19 (1.16–1.22) | 0.57 | 5.3 × 10−50 | 1.18 (1.12–1.24) | 0.09 | 1.7 × 10−9 |

| Amphetamine UD | 1.27 (1.21–1.33) | 0.67 | 7.3 × 10−25 | 1.07 (0.97–1.18) | 0.01 | 0.185 |

| Cocaine UD | 1.29 (1.20–1.39) | 0.62 | 8.2 × 10−12 | 1.13 (0.95–1.34) | 0.03 | 0.159 |

| Cannabis UD | 1.23 (1.18–1.29) | 0.49 | 1.1 × 10−19 | 1.14 (1.03–1.26) | 0.04 | 0.011 |

| Opioid UD | 1.27 (1.17–1.38) | 0.54 | 7.8 × 10−9 | 1.24 (1.03–1.50) | 0.08 | 0.024 |

| Sedative UD | 1.31 (1.25–1.37) | 0.89 | 9.8 × 10−30 | 1.29 (1.15–1.44) | 0.14 | 5.9 × 10−6 |

| EO | 1.23 (1.18–1.28) | 0.54 | 7.7 × 10−24 | 1.16 (1.06–1.27) | 0.05 | 1.9 × 10−3 |

| Ever‐smoking versus never‐smoking | 1.07 (1.05–1.09) | 0.19 | 1.5 × 10−12 | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) | <0.01 | 0.917 |

| Quantitative | β (95% CI) | R 2 [%] | P | β (95% CI) | R 2 [%] | P |

| FTND | 0.16 (0.09–0.22) | 0.56 | 1.4 × 10−6 | 0.26 (0.11–0.41) | 0.27 | 7.9 × 10−4 |

| CPD | 0.24 (0.15–0.33) | 0.08 | 1.8 × 10−7 | 0.20 (−0.01–0.41) | 0.01 | 0.056 |

| Number of admissions | 0.26 (0.17–0.35) | 0.35 | 4.7 × 10−9 | 0.09 (−0.12–0.30) | 0.01 | 0.403 |

To account for multiple testing, the significance level was set to 0.05/20 = 2.5 × 10−3. BPD, bipolar disorder; CPD, cigarettes per day; EO, early onset of addiction as assessed by admission to in‐patient addiction treatment before reaching the age of 26 years; FTND, Fagerström Test of nicotine dependence; PRS, polygenic risk scores; UD, use disorder; SCZ, schizophrenia. Ever‐smoking was assessed by ever smokers against never smokers. The estimate for CPD corresponds to number of cigarettes. To facilitate comparison of effects, the PRSs were scaled to give an OR of 2 for their corresponding disorder.

We excluded known BPD and SCZ cases from the analyses of the correlation of the PRSs with addiction and smoking. We computed the PRSs for individuals diagnosed with alcohol and substance use disorders at the SAA National Center of Addiction Medicine (http://saa.is/english/saa‐national‐center‐of‐addiction‐medicine) as well as controls and found that higher SCZ‐PRS associated with increased risk of alcohol and substance use disorders (P = 7.8 × 10−9–5.3 × 10−50). Higher BPD‐PRS was also associated with increased risk of alcohol use disorder (P = 1.7 × 10−9) and sedative use disorder (P = 5.9 × 10−6) (Table 2). The effect for alcohol and substance use disorders range from 1.19 to 1.31, for the SCZ‐PRS, and from 1.07 to 1.29 for the BPD‐PRS. Early onset (EO) of substance use problems and a chronic relapsing pattern are the hallmarks of severe addiction. Similarly, low age at first treatment and repeated admissions for treatment are indicators of addiction severity. To assess the PRSs as predictors of severity of addiction, we studied individuals first admitted at age 25 or younger (EO, Early Onset) and number of admissions. Higher SCZ‐PRS was associated with increased risk of EO (OR = 1.23, P = 7.7 × 10−24) and increased number of admissions (β = 0.26, P = 4.7 × 10−9), and higher BPD‐PRS was associated with increased risk of EO (OR = 1.16, P = 1.9 × 10−3).

Substance abuse and addiction have higher prevalence in men than women (Becker & Hu 2008). To explore sex‐effects, we tested for an interaction between sex and PRS and found significant interactions (P < 0.05) for SCZ‐PRS in alcohol and cocaine use disorders. Sex‐stratified analysis revealed 1.37 and 1.94 times larger effect for SCZ‐PRS on alcohol and cocaine use disorder, respectively, in women (Supporting Information Table S1).

Next, we tested the SCZ‐PRS and BPD‐PRS for association with ND, assessed by the FTND, and its proxy, CPD. Higher SCZ‐PRS was associated with increasing FTND (β = 0.16, P = 1.4 × 10−6) and CPD (β = 0.24, P = 1.8 × 10−7), while higher BPD‐PRS was only associated with increasing FTND (β = 0.26, P = 7.9 × 10−4) (Table 2). When individuals admitted to treatment for alcohol or drug addiction were excluded, only the association between SCZ‐PRS and CPD remained significant (Supporting Information Table S2). The fraction of subjects treated for addiction in the FTND and CPD samples is about 36 percent and 12 percent, respectively, perhaps explaining why the effect of the SCZ‐PRS changes less for CPD, in comparison with that for FTND, when treated individuals are excluded (Table 2 and Supporting Information Table S2). Smoking and nicotine addiction are much more prevalent among individuals with alcohol and substance use disorders. Treated subjects have higher CPD (β = 4.9 CPD, P = 2.6 × 10−224), higher FTND (β = 0.28 FTND, P = 2.8 × 10−90) and among smokers, higher SCZ‐PRSs (OR = 1.16, P = 2.6 × 10−25). The association of the SCZ‐PRS with smoking and ND might therefore be primarily through an effect on the risk of alcohol or substance use disorders (Supporting Information Table S2). Ever smokers have higher SCZ‐PRS than never smokers (OR = 1.07, P = 1.5 × 10−12) (Table 2), and the difference remained significant (OR = 1.05, P = 5.6 × 10−7) after removing individuals admitted to treatment (Supporting Information Table S2). However, it stands to reason that individuals with substance use disorders that have not been diagnosed/treated would also contribute strongly to the correlation with smoking and ND.

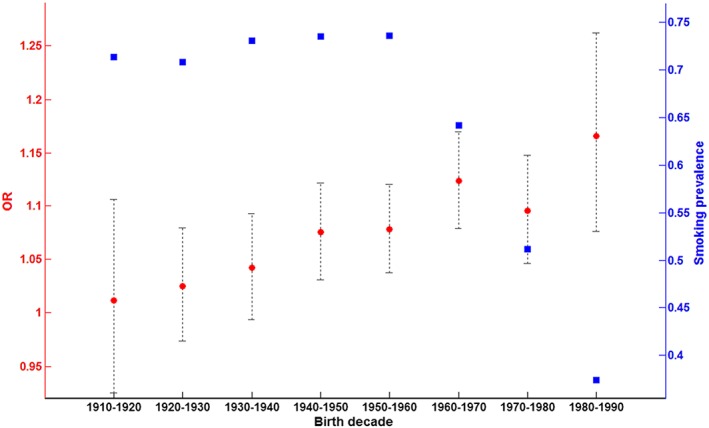

There has been about threefold reduction in the smoking rate in the general Icelandic population over the last three decades (http://www.statice.is/statistics/society/health/lifestyle‐and‐health/), providing a possibility to explore the effects of increased smoking restrictions (legal and social) on the relationships between the psychosis PRSs and smoking behavior. Stratifying the deCODE smoking sample by decade of birth showed the fraction of ever‐smokers dramatically decreasing for subjects born after 1960 (Fig. 1). Interaction between SCZ‐PRS and year of birth in smoking tested significant (P = 5.01 × 10−4), and analyzing the association to SCZ‐PRS showed the OR increasing with decade of birth (Fig. 1). The contribution from SCZ‐PRS to the risk of smoking discernibly increases as the smoking rate declines in the population. This is in agreement with the observed increased psychiatric co‐morbidity among current smokers (Talati, Keyes & Hasin 2016). Excluding subjects with addiction treatment admission did not change the trend between OR and decade of birth (Supporting Information Fig. S1), suggesting the increasing OR with decade of birth is not simply due to biased distribution of subjects treated for addiction. As smoking is a risk factor for many of the disorders studied at deCODE, our ever‐smoking versus never‐smoking sample is biased towards smokers, explaining the high prevalence for ever‐smoking (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of self‐reported ever‐smoking and odds ratio of schizophrenia polygenic risk scores (PRSs) for ever‐smoking by decade of birth. Prevalence of self‐reported ever‐smoking by decade of birth is shown in blue (right y‐axis). The odds ratio (OR) of SCZ‐PRSs for ever‐smoking is shown in red (left y‐axis). The 95% CI for OR is depicted by black error bars

A moderate degree of correlation, with an R 2 of 4.38 percent, was observed between the SCZ‐PRS and BPD‐PRS. Only alcohol use disorder was nominally associated (OR = 1.09, R 2 = 0.59 percent, P = 2.7 × 10−3) with BPD‐PRS when including SCZ‐PRS as a covariate. This suggests that the observed risk to smoking and substance use disorder from BPD‐PRS is largely explained by a genetic basis common to SCZ and BPD. We note that SCZ‐PRS is a slightly better predictor for BPD than BPD‐PRS (Table 2). However, the BPD‐PRS is derived from a less powered meta‐analysis and only explains 0.90 percent of the variance in BPD in Iceland, which is about 20 percent of that explained by SCZ‐PRS in SCZ.

Discussion

Our results support the notion of common genetic roots of the observed co‐morbidity between addiction and psychotic disorders SCZ and BPD, as opposed to solely being a direct consequence. This conclusion has some similarity with the outcome from analyses of twin data for addiction and common psychiatric disorders, such as depression and anxiety disorders, suggesting that the patterns of lifetime co‐morbidity result largely from the effects of genetic factors (Kendler et al. 2003). However, demonstrating shared genetics does not necessarily point to true biological pleiotropy, and here, various scenarios involving mediated pleiotropy are possible (Gage et al. 2016). It can be rather difficult to dissect such relationships, as evidenced by the case of CHRNA5–CHRNA3–CHRNB4 locus, smoking and lung cancer (Gage et al. 2016). The correlation of the psychosis PRSs with both addiction and creativity (Power et al. 2015) also brings up the issue of the relationship between addiction and creativity. Brendan Behan was not the only ‘drinker with a writing problem’, and it is no secret that many of the most creatively talented people of arts and letters also battle addiction. Further studies are required to understand the genetics of these intriguing relationships more fully. Joint analyses utilizing PRSs based on well‐powered GWAS studies, for SCZ and BPD as well as PRSs for both addiction and depression/anxiety disorders, will undoubtedly be informative. Results from additional large GWAS studies may pave the way to bidirectional Mendelian randomization studies aimed at dissecting the causal pathways.

We note that risk to substance use disorders seems to be slightly less for the BPD‐PRS than the SCZ‐PRS (Table 2). However, this could easily be due to the BPD‐PRS being derived from a less powered meta‐analysis. We also observed a difference between the sexes, with the SCZ‐PRS clearly conferring higher risk in women than men for alcohol and cocaine use disorders. Our previous studies of the familiality of addiction in this sample found higher familiality for women compared with men (Tyrfingsson et al. 2010). While the increased familiality could be due to either genetics or common environment (the strong influence the mother has on her children), addiction is more prevalent among men, and this might be indicative of a higher barrier to develop addiction among women (Prescott, Aggen & Kendler 1999; Prescott 2002) and/or a higher barrier to seeking treatment. A higher liability threshold is a likely explanation for the increased risk conferred by the SCZ‐PRS in women in our sample, with men perhaps being more susceptible to the effects of environment.

It is of special interest that the impact of the SCZ liability score on smoking behavior seems to be on the rise as the overall prevalence of smoking declines. Psychiatric vulnerability is increasing among regular smokers. First, smoking rates for both SCZ and BPD patients remain quite high, while the population prevalence of smoking drops. This contributes to increased psychiatric co‐morbidity among current smokers and in younger birth cohorts, as has been observed (Talati et al. 2016). Second, we have shown here that a similar trend is observed for those within the population not diagnosed with SCZ or BPD but having high PRSs for SCZ or BPD. These observations have considerable implications for public health programs in that anti‐smoking measures and smoking cessation programs may need to be tailored towards modifying the smoking behaviors of both psychiatric patients and those among the population that have high psychosis PRSs. Many view regular smoking simply as a bad habit, but our current findings increasingly cast the behavior as a psychiatric condition sharing genetic risk with SCZ and BPD.

Conflict of Interest

G. W. R., A. I., G. B., S. O., S. S., H. S., D. F. G., T. E. T. and K. S. are employees of deCODE genetics/Amgen.

Authors Contribution

GWR, AI, JE, SS, HS, DFG, TET and KS were involved in study design. GB, ES, IH, VR and TT were involved in cohort ascertainment, phenotypic characterization and recruitment. GWR, AI, JE, SO, SS and DFG were involved in informatics and carried out statistical analysis. GWR, SS, HS, DFG, TET and KS were involved in planning and supervising the study. GWR, JE, SS, HS, DFG, TET and KS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Prevalence of self‐reported ever‐smoking and odds ratio of SCZ‐PRS for ever‐smoking for subjects without treatment for alcohol or drug addiction

Figure S2. Distribution of SCZ‐ and BPD‐PRS

Figure S3. Variance explained by the PRSs in their corresponding disorders in Iceland

Table S1. Associations between PRS and smoking phenotypes in individuals without admission to the addiction treatment center

Table S2. Sex‐specific (males/females) associations between SCZ‐PRS and addiction phenotypes

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the participants and staff at the Patient Recruitment Center. This study was funded in part by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) (R01‐DA017932 and R01‐DA034076), and it received support from the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme under the Marie Curie Industry Academia Partnership and Pathways (PsychDPC, GA 286213).

Reginsson, G. W. , Ingason, A. , Euesden, J. , Bjornsdottir, G. , Olafsson, S. , Sigurdsson, E. , Oskarsson, H. , Tyrfingsson, T. , Runarsdottir, V. , Hansdottir, I. , Steinberg, S. , Stefansson, H. , Gudbjartsson, D. F. , Thorgeirsson, T. E. , and Stefansson, K. (2018) Polygenic risk scores for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder associate with addiction. Addiction Biology, 23: 485–492. doi: 10.1111/adb.12496.

References

- Becker JB, Hu M (2008) Sex differences in drug abuse. Front Neuroendocrinol 29:36–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Compton WM, Saha TD, Goldstein BI, Ruan WJ, Huang B, Grant BF (2016) Epidemiology of DSM‐5 bipolar I disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions – III. J Psychiatr Res 84:310–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulik‐Sullivan B, Finucane HK, Anttila V, Gusev A, Day FR, Loh PR, Duncan L, Perry JR, Patterson N, Robinson EB, Daly MJ, Price AL, Neale BM (2015a) An atlas of genetic correlations across human diseases and traits. Nat Genet 47:1236–1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulik‐Sullivan BK, Loh PR, Finucane HK, Ripke S, Yang J, Patterson N, Daly MJ, Price AL, Neale BM (2015b) LD score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome‐wide association studies. Nat Genet 47:291–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerullo MA, Strakowski SM (2007) The prevalence and significance of substance use disorders in bipolar type I and II disorder. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 2:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage SH, Davey Smith G, Ware JJ, Flint J, Munafo MR (2016) G = E: What GWAS Can Tell Us about the Environment. PLoS Genet 12:e1005765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman D, Oroszi G, Ducci F (2005) The genetics of addictions: uncovering the genes. Nat Rev Genet 6:521–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudbjartsson DF, Helgason H, Gudjonsson SA, Zink F, Oddson A, Gylfason A, Besenbacher S, Magnusson G, Halldorsson BV, Hjartarson E, Sigurdsson GT, Stacey SN, Frigge ML, Holm H, Saemundsdottir J, Helgadottir HT, Johannsdottir H, Sigfusson G, Thorgeirsson G, Sverrisson JT, Gretarsdottir S, Walters GB, Rafnar T, Thjodleifsson B, Bjornsson ES, Olafsson S, Thorarinsdottir H, Steingrimsdottir T, Gudmundsdottir TS, Theodors A, Jonasson JG, Sigurdsson A, Bjornsdottir G, Jonsson JJ, Thorarensen O, Ludvigsson P, Gudbjartsson H, Eyjolfsson GI, Sigurdardottir O, Olafsson I, Arnar DO, Magnusson OT, Kong A, Masson G, Thorsteinsdottir U, Helgason A, Sulem P, Stefansson K (2015) Large‐scale whole‐genome sequencing of the Icelandic population. Nat Genet 47:435–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartz SM, Pato CN, Medeiros H, Cavazos‐Rehg P, Sobell JL, Knowles JA, Bierut LJ, Pato MT (2014) Comorbidity of severe psychotic disorders with measures of substance use. JAMA Psychiat 71:248–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO (1991) The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict 86:1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JG, Diaz FJ, Lopez L, de Leon J (2015) A combined analysis of worldwide studies demonstrates an association between bipolar disorder and tobacco smoking behaviors in adults. Bipolar Disord 17:575–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Prescott CA, Myers J, Neale MC (2003) The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60:929–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenneson A, Funderburk JS, Maisto SA (2013) Substance use disorders increase the odds of subsequent mood disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend 133:338–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ (1985) The self‐medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. Am J Psychiatry 142:1259–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manolio TA, Collins FS, Cox NJ, Goldstein DB, Hindorff LA, Hunter DJ, McCarthy MI, Ramos EM, Cardon LR, Chakravarti A, Cho JH, Guttmacher AE, Kong A, Kruglyak L, Mardis E, Rotimi CN, Slatkin M, Valle D, Whittemore AS, Boehnke M, Clark AG, Eichler EE, Gibson G, Haines JL, Mackay TF, McCarroll SA, Visscher PM (2009) Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature 461:747–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marconi A, Di Forti M, Lewis CM, Murray RM, Vassos E (2016) Meta‐analysis of the association between the level of cannabis use and risk of psychosis. Schizophr Bull 42:1262–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolese HC, Malchy L, Negrete JC, Tempier R, Gill K (2004) Drug and alcohol use among patients with schizophrenia and related psychoses: levels and consequences. Schizophr Res 67:157–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Saha S, Chant D, Welham J (2008) Schizophrenia: a concise overview of incidence, prevalence, and mortality. Epidemiol Rev 30:67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn DP, Levy G, Nazareth I, Petersen I, Islam A, King MB (2007) Relative risk of cardiovascular and cancer mortality in people with severe mental illness from the United Kingdom's General Practice Rsearch Database. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64:242–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PGC‐Bipolar‐Disorder‐Working‐Group (2011) Large‐scale genome‐wide association analysis of bipolar disorder identifies a new susceptibility locus near ODZ4. Nat Genet 43:977–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PGC‐Schizophrenia‐Working‐Group (2014) Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia‐associated genetic loci. Nature 511:421–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power RA, Steinberg S, Bjornsdottir G, Rietveld CA, Abdellaoui A, Nivard MM, Johannesson M, Galesloot TE, Hottenga JJ, Willemsen G, Cesarini D, Benjamin DJ, Magnusson PK, Ullen F, Tiemeier H, Hofman A, van Rooij FJ, Walters GB, Sigurdsson E, Thorgeirsson TE, Ingason A, Helgason A, Kong A, Kiemeney LA, Koellinger P, Boomsma DI, Gudbjartsson D, Stefansson H, Stefansson K (2015) Polygenic risk scores for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder predict creativity. Nat Neurosci 18:953–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power RA, Verweij KJ, Zuhair M, Montgomery GW, Henders AK, Heath AC, Madden PA, Medland SE, Wray NR, Martin NG (2014) Genetic predisposition to schizophrenia associated with increased use of cannabis. Mol Psychiatry 19:1201–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott CA (2002) Sex differences in the genetic risk for alcoholism. Alcohol Res Health: the journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism 26:264–273. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott CA, Aggen SH, Kendler KS (1999) Sex differences in the sources of genetic liability to alcohol abuse and dependence in a population‐based sample of U.S. twins. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 23:1136–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Barch DM, Wolf TJ, Mamah D, Csernansky JG (2008) Elevated rates of substance use disorders in non‐psychotic siblings of individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 106:294–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E (1978) Research diagnostic criteria: rationale and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 35:773–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talati A, Keyes KM, Hasin DS (2016) Changing relationships between smoking and psychiatric disorders across twentieth century birth cohorts: clinical and research implications. Mol Psychiatry 21:464–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorgeirsson TE, Geller F, Sulem P, Rafnar T, Wiste A, Magnusson KP, Manolescu A, Thorleifsson G, Stefansson H, Ingason A, Stacey SN, Bergthorsson JT, Thorlacius S, Gudmundsson J, Jonsson T, Jakobsdottir M, Saemundsdottir J, Olafsdottir O, Gudmundsson LJ, Bjornsdottir G, Kristjansson K, Skuladottir H, Isaksson HJ, Gudbjartsson T, Jones GT, Mueller T, Gottsater A, Flex A, Aben KK, de Vegt F, Mulders PF, Isla D, Vidal MJ, Asin L, Saez B, Murillo L, Blondal T, Kolbeinsson H, Stefansson JG, Hansdottir I, Runarsdottir V, Pola R, Lindblad B, van Rij AM, Dieplinger B, Haltmayer M, Mayordomo JI, Kiemeney LA, Matthiasson SE, Oskarsson H, Tyrfingsson T, Gudbjartsson DF, Gulcher JR, Jonsson S, Thorsteinsdottir U, Kong A, Stefansson K (2008) A variant associated with nicotine dependence, lung cancer and peripheral arterial disease. Nature 452:638–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrfingsson T, Thorgeirsson TE, Geller F, Runarsdottir V, Hansdottir I, Bjornsdottir G, Wiste AK, Jonsdottir GA, Stefansson H, Gulcher JR, Oskarsson H, Gudbjartsson D, Stefansson K (2010) Addictions and their familiality in Iceland. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1187:208–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Prevalence of self‐reported ever‐smoking and odds ratio of SCZ‐PRS for ever‐smoking for subjects without treatment for alcohol or drug addiction

Figure S2. Distribution of SCZ‐ and BPD‐PRS

Figure S3. Variance explained by the PRSs in their corresponding disorders in Iceland

Table S1. Associations between PRS and smoking phenotypes in individuals without admission to the addiction treatment center

Table S2. Sex‐specific (males/females) associations between SCZ‐PRS and addiction phenotypes