Abstract

Background

Amomum compactum is one of the basic species of the traditional herbal medicine amomi fructus rotundus, with great pharmacology effect. The system position of A. compactum is not clear yet, and the introduction of this plant has been hindered by many plant diseases. However, the correlational molecular studies are relatively scarce.

Methods

The total chloroplast (cp) DNA was extracted according to previous studies, and then sequenced by 454 GS FLX Titanium platform. Sequence assembly was complished by Newbler. Genome annotation was preformed by CPGAVAS and tRNA-SCAN. Then, general characteristics of the A. compactum cp genome and genome comparsion with three Zingiberaceae species was analyzed by corresponding softwares. Additionally, phylogenetical trees were reconstructed, based on the shared protein-coding gene sequences among 15 plant taxa by maximum parsimony (MP) and maximum likelihood (ML) methods.

Results

The A. compactum cp genome with a classic quadripartite structure, consisting of a pair of reverse complement repeat regions (IRa/IRb) of 29,824 bp, a large single copy (LSC, 88,535 bp) region as well as a small single copy (SSC, 15,370 bp) region, is 163,553 bp in total size. The total GC content of this cp genome is 36.0%. The A. compactum cp genome owns 135 functional genes, that 113 genes are unique, containing eighty protein-coding genes, twenty-nine tRNA (transfer RNA) genes and four rRNA (ribosomal RNA) genes. Codon usage of the A. compactum cp genome is biased toward codons ending with A/T. Total 58 SSR loci and 24 large repeats are detected in the A. compactum cp genome. Relative to three other Zingiberaceae cp genomes, the A. compactum cp genome exhibits an obvious expansion in the IR regions. In A. compactum cp genome, the ycf1 pseudogene is 2969 bp away from the IRa/SSC border, whereas in other Zingiberaceae species, it is only 4–5 bp away from the IRa/SSC border. Comparative cp genome sequences analysis of A. compactum with other Zingiberaceae reveals that the gene order and gene content differ slightly among Zingiberaceae species. The phylogenetic analysis based on 67 protein-coding gene sequences supports the phylogenetic position of A. compactum.

Conclusions

The study has identified unique features of the A. compactum cp genome which would be helpful for us to understand the cp genome evolution and offer useful information for phylogenetics and further studies of this traditional medicinal plant.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13020-018-0164-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Amomum compactum, Chloroplast genome, SSR, Phylogeny, High-throughput sequencing technology

Background

Chloroplasts can provide necessary energy for plants growth as photosynthetic organelles, which also participate in other major life activities such as starch storage, sugar synthesis and many critical biological metabolic pathways. As circular DNA molecules, cp genomes mainly vary from 120 to 160 kb in size with a typical quadripartite organization in angiosperms [1]. Two reverse complement copies of IR region (20–28 kb) separate the whole cp genome into a LSC region (80–90 kb) and a SSC region (16–27 kb) [2]. In angiosperms, cp genomes usually encode approximately 80 unique proteins, 30 tRNAs and four rRNAs. Previous studies have corroborated that cp gene order, gene content, and genome organization are highly conserved in plants [3, 4]. Owing to the high conservation and monolepsis, cp genomes are widely used in species identification, phyletic evolution studies and genetic engineering. The availability of whole cp genomes has helped to resolve phylogenetic relationships among major clades of angiosperms with greater accuracy [5, 6]. Nevertheless, with the number of cp genomes increasing, gene losses, structural rearrangements and IR contractions/expansions have been reported, which can also be exploited for the reconstruction of plant phylogenies [7–9].

Amomum compactum (genus Amomum, family Zingiberaceae) is one of the basic species of the traditional Chinese medicine amomi fructus rotundus, which is mainly produced in Vietnam and Thailand and is cultivated as a medicinal plant in the Guangdong, Guangxi and Yunnan provinces of China with great pharmacology effect. However, bacterial wilt, damping-off, leaf spot and other major plant diseases have become a severe obstacle for the introduction of this plant. Many plants belonging to the Zingiberaceae family are used as important seasoning and medicinal plants, such as Zingiber officinale, Amomum villosum, Curcuma longa, Zingiber mioga, Elettaria cardamomum, and Alpinia officinarum. In addition, previous studies have shown that the efficacy, chemical composition and pharmacological effects among the five genera of Zingiberaceae are strongly correlated. It is of great significance and broad interest to investigate the genetic relationships of traditional Chinese medicinal plants to find alternative medicinal plants. With the number of whole cp genomes in the Zingiberaceae increasing, the cp genome sequences of other species in Zingiberaceae are becoming easier to be assembled. However, studies of amomi fructus rotundus are scarce both inside and outside China, especially molecular studies.

This study reports the assembly, annotation and structural analysis of A. compactum cp genome for the first time. And to reveal the structure of this cp genome, we compare the organization (IR expansion/contraction and divergent regions) of complete cp genomes between A. compactum and other Zingiberaceae species. We also provide the result of phylogenetic analyses on basis of 67 protein-coding gene sequences from A. compactum and 14 monocot cp genomes.

Methods

DNA extraction and sequencing

Fresh A. compactum leaves were acquired from cultivated bases in Guangdong Province, China. The total cp DNA was extracted from roughly 100 g of leaves through an improved method by Li et al. [10]. The quality of cp DNA was checked by Nanodrop-2000 spectrometer (Nanodrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA), and agarose gel electrophoresis. Pure cp DNA was used for shotgun library construction with 454 GS FLX Titanium platform. The obtained SFF file was preprocessed by trimming short (L < 50 bp) and low-quality (Q < 20) reads. Trimmed reads were assembled using Newbler V2.6 (GS FLX De Novo Assembler Software). In order to verify the assembly, the four junctional regions were further confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

Genome assembly and annotation

Preliminary gene annotation of this cp genome was performed by CpGAVAS, a program available online (http://www.herbalgenomics.org/0506/cpgavas) [11]. The position of each gene was then manually corrected by Apollo [12] after alignment to the reference genomes by MEGA 5.0. In addition, according to start and stop codons, minor revisions were performed. The tRNAs were further confirmed by the online tool tRNAscan-SE with default settings (http://lowelab.ucsc.edu/tRNAscan-SE/). [13]. Then, the circular map of this cp genome was accomplished by OrganellarGenomeDRAW program (http://ogdraw.mpimp-golm.mpg.de/) [14]. Finally, the complete cp genome of A. compactum was submitted to NCBI GenBank database (Accession Number: MG000589).

Sequence analyses

Relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) values, which were used to research the features of variations in synonymous and nonsynonymous codon usage by disregarding the composition impact of amino acid, were determined using MEGA 6.0 [15]. Additionally, GC content and codon usage were determined by MEGA 6.0. SSRs (simple sequence repeats) loci were detected by MISA software (http://pgrc.ipk-gatersleben.de/misa/), with following thresholds: ten, six, five, five, five, and five repeat units for mono-nucleotide, di-nucleotide, tri-nucleotide, tetra-nucleotide, penta-nucleotide, and hexa-nucleotide SSRs, respectively. To analyze the repeat structure, REPuter [16] (http://bibiserv.techfak.uni-bielefeld.de/reputer/) was performed to detect forward (direct) and palindromic (inverted) repeats in the cp genome. The minimum repeat unit was set to 30 bp in length, the identity of repeats was set to > 90%, and the Hamming distance equals three. All identified results were verified and redundant repeats were manually removed.

Genome comparison

Pairwise alignments of several cp genome sequences were conducted by MUMmer [17], and the dot plots were drawn using a Perl script. The complete cp genomes of A. compactum and three other Zingiberaceae species (Additional file 1), Curcuma flaviflora (KR967361), Curcuma roscoeana (KF601574), and Zingiber spectabile (JX088661), were used for comparative analysis by mVISTA program (http://genome.lbl.gov/vista/index.shtml) [18] in Shuffle-LAGAN mode. A. compactum was set as the reference.

Phylogenomic analysis

To examine the phylogenetic position of A. compactum, 14 complete chloroplast genomes were downloaded from NCBI. The 67 shared protein-coding gene sequences were extracted using a Python script and aligned separately by ClustalW2. Phylogenetical trees were reconstructed based on 67 concatenated protein-coding gene sequences by MP and ML methods. The best-fitting model was filtrated by jModelTest 2.1.7 through the Akaike information criterion (AIC) [19]. The MP tree was reconstructed by PAUP ver. 4.0b10 [20] with a heuristic search, while ML analysis was calculated by RAxML-HPC 2.7.6.3 on XSEDE in the CIPRES Science Gateway (http://www.phylo.org/) with default parameters. Based on APGIII, Fritillaria cirrhosa was set as an outgroup. Both MP and ML analyses used 1000 bootstrap replicates.

The Minimum Standards of Reporting Checklist includes details of the experimental design, statistics, and resources used in this study.

Results and discussion

General characteristics of the A. compactum cp genome

The complete cp genome sequence of A. compactum is 163,553 bp in length with a obvious quadripartite structure (Fig. 1). A pair of inverted region (IR) with 29,824 bp in length partition the rest sequence into a LSC region (88,535 bp) and a SSC region (15,370 bp) (Table 1). The universal GC content of this cp sequence was 36.0%, which has been reported to act a significant role in evolution of genomic structures. Nevertheless, the overall GC content is unequally distributed across the cp genome, which is lowest in SSC region (29.8%) but highest in IR regions (41.1%), followed by LSC region (33.7%).

Fig. 1.

A. compactum cp genome map. Genes drawn outside the circle are counterclockwise, whereas inside are transcribed clockwise. Genes are color-coded according to different functional groups. The darker gray represents GC content in the inner circle, conversely the lighter one represents AT content

Table 1.

Base composition in the A. compactum cp genome

| T(U)% | C% | A% | G% | Length (bp) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSC | 33.8 | 17.2 | 32.5 | 16.5 | 88,535 |

| IR | 28.8 | 19.8 | 30.1 | 21.3 | 29,824 |

| SSC | 34.3 | 15.6 | 35.9 | 14.2 | 15,370 |

| Total | 32.3 | 18.3 | 31.7 | 17.8 | 163,553 |

| CDS | 31.6 | 17.2 | 31.5 | 19.8 | 79,701 |

| 1st position | 24 | 18.2 | 31.3 | 26.7 | 26,567 |

| 2nd position | 32 | 20.2 | 30.0 | 17.4 | 26,567 |

| 3rd position | 39 | 13.1 | 33.1 | 15.3 | 26,567 |

CDS protein-coding regions

As shown in Fig. 1, the A. compactum cp genome totally encodes 135 functional genes, that 113 are unique, containing eighty protein-coding genes, twenty-nine tRNAs and four rRNAs (Table 2). Among the functional genes, all rRNAs, eight tRNAs and seven protein-coding genes are duplicated in IR regions. The LSC region includes 60 protein-coding genes and 21 tRNAs, whereas the SSC region includes 11 protein-coding genes and one tRNA gene. Among the protein-coding genes, 72 are single-copy, whereas eight are duplicated. Among the tRNA genes, 20 are single-copy genes and nine are duplicated. Among the 113 unique genes, 13 include one intron (eight protein-coding and five tRNAs) and three (ycf3, clpP, and rps12) include two introns (Table 2). Unusually, the rps12 gene is trans-spliced, of which the 5′ end is situated in LSC region whereas two replicative 3′ ends are located in IRa and IRb regions respectively. What’s more, the ndhA gene contains the longest intron region (1033 bp).

Table 2.

Gene content of the A. compactum cp genome

| Gene category | Gene group | Gene name |

|---|---|---|

| Self-replication | rRNA genes | rrn16c, rrn23c, rrn5c, rrn4.5c |

| tRNA genes | trnH-GUGc, trnK-UUUa, trnQ-UUG, trnS-GCU, trnC-GCA, trnD-GUC, trnY-GUA, trnE-UUC, trnR-UCU, trnT-GGU, trnS-UGA, trnG-GCCc, trnfM-CAU, trnS-GGA, trnT-UGU, trnL-UAAa, trnF-GAA, trnV-UACa, trnW-CCA, trnP-UGG, trnI-CAUc, trnL-CAAc, trnV-GACc, trnI-GAUa, c, trnA-UGCa, c, trnR-ACGc, trnN-GUUc, trnL-UAG, trnM-CAU | |

| Small subunit of ribosome | rps4, rps14, rps18, rps2, rps12b, c, rps11, rps8, rps3, rps19, rps7c, rps15, rps16a | |

| Large subunit of ribosome | rpl33, rpl20, rpl36, rpl14, rpl16a, rpl22, rpl2a, c, rpl23c, rpl32 | |

| DNA dependent RNA polymerase | rpoB, rpoC1a, rpoC2, rpoA | |

| Translational initiation factor | infA | |

| Genes for photosynthesis | Subunits of NADH dehydrogenase | ndhAa, ndhBa, c, ndhC, ndhD, ndhE, ndhF, ndhG, ndhH, ndhI, ndhJ, ndhK |

| Subunits of photosystem I | psaA, psaB, psaC, psaI, psaJ, ycf3b, ycf4 | |

| Subunits of photosystem II | psbA, psbB, psbC, psbD, psbE, psbF, psbH, psbI, psbJ, psbK, psbL, psbM, psbN, psbT, psbZ | |

| Subunits of cytochrome b/f complex | petN, petA, petL, petG, petBa, petD | |

| Subunits of ATP synthase | atpI, atpH, atpFa, atpA, atpE, atpB | |

| Large subunit of rubisco | rbcL | |

| Genes of unknown function | Open reading frames (ORF, ycf) | ycf1, ycf15c, ycf2c |

| Pseudogenes | ycf1 |

aGene with one intron

bGene with two introns

cGene with two copies

The protein-coding gene sequences are 79,701 bp in length, which comprise 26,567 codons. And the usage frequency of codon was counted and exhibited in Table 3. In protein-coding sequences (CDSs), the AT content are 55.3% at the first codon positions, 62.0% at the second codon positions and 72.1% at the third codon positions, respectively (Table 1). Most protein-coding genes in land plant cp genomes use the standard ATG as the initiation codon. However, in the A. compactum cp genome, two genes use alternatives to ATG as start codon, as following: ATC for ndhD and ATA for rpl2. Relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) is a statistics of uneven usage of synonymous and nonsynonymous codons in the coding sequences. An RSCU value < 1.00 indicates that the use of a codon is less frequent than expected, whereas a codon used more frequently will attain an RSCU value > 1.00. A total of 96.7% (29/30) of preferred synonymous codons, i.e., RSCU values > 1, end with A/U, whereas 90.6% (29/32) of non-preferred synonymous codons, i.e., RSCU values < 1, end with G/C. This codon usage pattern is similar with other reported cp genomes [21, 22], which might be driven by the high proportion of A/T. The usage of the start codon (ATG) and UGG (coding TRP) show no bias (RSCU value = 1).

Table 3.

Codon-anticodon recognition patterns and codon usage in the A. compactum cp genome

| Amino acid | Codon | No. | RSCU | tRNA | Amino acid | Codon | Count | RSCU | tRNA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phe | UUU | 971 | 1.31 | Tyr | UAU | 811 | 1.57 | ||

| Phe | UUC | 516 | 0.69 | trnF-GAA | Tyr | UAC | 221 | 0.43 | trnY-GUA |

| Leu | UUA | 892 | 1.96 | trnL-UAA | Stop | UAA | 48 | 1.66 | |

| Leu | UUG | 559 | 1.23 | trnL-CAA | Stop | UAG | 22 | 0.76 | |

| Leu | CUU | 567 | 1.25 | His | CAU | 519 | 1.6 | ||

| Leu | CUC | 181 | 0.4 | His | CAC | 129 | 0.4 | trnH-GUG | |

| Leu | CUA | 381 | 0.84 | trnL-UAG | Gln | CAA | 706 | 1.54 | trnQ-UUG |

| Leu | CUG | 151 | 0.33 | Gln | CAG | 210 | 0.46 | ||

| Ile | AUU | 1146 | 1.47 | Asn | AAU | 989 | 1.55 | ||

| Ile | AUC | 426 | 0.55 | trnI-GAU | Asn | AAC | 289 | 0.45 | trnN-GUU |

| Ile | AUA | 763 | 0.98 | trnI-CAU | Lys | AAA | 1114 | 1.49 | trnK-UUU |

| Met | AUG | 614 | 1 | trn(f)M-CAU | Lys | AAG | 383 | 0.51 | |

| Val | GUU | 521 | 1.45 | Asp | GAU | 875 | 1.64 | ||

| Val | GUC | 159 | 0.44 | trnV-GAC | Asp | GAC | 192 | 0.36 | trnD-GUC |

| Val | GUA | 559 | 1.56 | trnV-UAC | Glu | GAA | 1125 | 1.53 | trnE-UUC |

| Val | GUG | 194 | 0.54 | Glu | GAG | 350 | 0.47 | ||

| Ser | UCU | 598 | 1.74 | Cys | UGU | 232 | 1.56 | ||

| Ser | UCC | 337 | 0.98 | trnS-GGA | Cys | UGC | 66 | 0.44 | trnC-GCA |

| Ser | UCA | 412 | 1.2 | trnS-UGA | Stop | UGA | 17 | 0.59 | |

| Ser | UCG | 182 | 0.53 | Trp | UGG | 452 | 1 | trnW-CCA | |

| Pro | CCU | 442 | 1.62 | Arg | CGU | 365 | 1.37 | trnR-ACG | |

| Pro | CCC | 202 | 0.74 | Arg | CGC | 86 | 0.32 | ||

| Pro | CCA | 325 | 1.19 | trnP-UGG | Arg | CGA | 342 | 1.29 | |

| Pro | CCG | 120 | 0.44 | Arg | CGG | 113 | 0.43 | ||

| Thr | ACU | 537 | 1.57 | Arg | AGA | 519 | 1.95 | trnR-UCU | |

| Thr | ACC | 237 | 0.7 | trnT-GGU | Arg | AGG | 168 | 0.63 | |

| Thr | ACA | 433 | 1.27 | trnT-UGU | Ser | AGU | 430 | 1.25 | |

| Thr | ACG | 157 | 0.46 | Ser | AGC | 102 | 0.3 | trnS-GCU | |

| Ala | GCU | 626 | 1.82 | Gly | GGU | 604 | 1.39 | ||

| Ala | GCC | 203 | 0.59 | Gly | GGC | 141 | 0.33 | trnG-GCC | |

| Ala | GCA | 434 | 1.26 | trnA-UGC | Gly | GGA | 714 | 1.65 | |

| Ala | GCG | 112 | 0.33 | Gly | GGG | 276 | 0.64 |

RSCU relative synonymous codon usage

Repeat and SSR analysis

SSRs are a class of tandemly repeated sequences that consists of 1–6 nucleotide repeat units. SSRs are important in plant typing and widely developed as molecular genetic markers for species identification. Total 58 SSRs loci were found in the A. compactum cp genome (Table 4), and 47 SSRs were only composed of A/T bases. Furthermore, 10 SSRs were composed of di-nucleotide (AT/TA) repeats, and one SSR was composed of trinucleotide (ATA) repeats. Obviously, the SSRs in the A. compactum cp genome were rich in A/T, which has been reported in many plant families [23–25]. Among these SSRs, 17 SSRs were situated in protein-coding genes and one was located in a tRNA gene. Furthermore, five were in coding regions and 12 in intronic regions. No tetra-, penta- or hexa-nucleotide repeats over 15 bp long was detected. REPuter allowed us to identify 24 repeats, including 13 forward and 11 palindromic repeats (Table 5). Almost all repeats were situated in the intronic and intergenic regions, although few of them were situated in protein-coding regions [26]. As reported in other genomes, the gene richest in repeats was ycf2, carrying two direct and two palindromic repeats.

Table 4.

Simple sequence repeats in the A. compactum cp genome

| cpSSR ID | Repeat motif | Length (bp) | Start | End | Region | Annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (T)10 | 10 | 3975 | 3984 | LSC | trnK-UUU |

| 2 | (A)10 | 10 | 4328 | 4337 | LSC | |

| 3 | (TA)6 | 12 | 4900 | 4911 | LSC | |

| 4 | (A)10 | 10 | 5287 | 5296 | LSC | rps16 intron |

| 5 | (A)11 | 11 | 6253 | 6263 | LSC | |

| 6 | (TA)6 | 12 | 6609 | 6620 | LSC | |

| 7 | (A)10 | 10 | 7204 | 7213 | LSC | |

| 8 | (AT)6 | 12 | 7521 | 7532 | LSC | |

| 9 | (A)10 | 10 | 7700 | 7709 | LSC | |

| 10 | (T)12 | 12 | 8633 | 8644 | LSC | |

| 11 | (A)13 | 13 | 14,885 | 14,897 | LSC | |

| 12 | (T)10 | 10 | 17,474 | 17,483 | LSC | |

| 13 | (A)10 | 10 | 19,831 | 19,840 | LSC | rpoC2 |

| 14 | (T)11 | 11 | 24,121 | 24,131 | LSC | rpoC1 intron |

| 15 | (A)10 | 10 | 28,802 | 28,811 | LSC | |

| 16 | (A)15 | 15 | 29,013 | 29,027 | LSC | |

| 17 | (A)11 | 11 | 30,868 | 30,878 | LSC | |

| 18 | (T)10 | 10 | 35,129 | 35,138 | LSC | |

| 19 | (TA)7 | 14 | 38,632 | 38,645 | LSC | |

| 20 | (A)12 | 12 | 39,292 | 39,303 | LSC | |

| 21 | (A)12 | 12 | 47,481 | 47,492 | LSC | |

| 22 | (T)10 | 10 | 48,986 | 48,995 | LSC | |

| 23 | (A)10 | 10 | 50,236 | 50,245 | LSC | |

| 24 | (AT)7 | 14 | 50,395 | 50,408 | LSC | |

| 25 | (T)10 | 10 | 51,829 | 51,838 | LSC | |

| 26 | (T)11 | 11 | 52,709 | 52,719 | LSC | |

| 27 | (ATA)5 | 15 | 54,345 | 54,359 | LSC | |

| 28 | (A)11 | 11 | 54,562 | 54,572 | LSC | |

| 29 | (T)10 | 10 | 58,778 | 58,787 | LSC | |

| 30 | (T)11 | 11 | 59,269 | 59,279 | LSC | |

| 31 | (A)12 | 12 | 60,919 | 60,930 | LSC | |

| 32 | (T)10 | 10 | 61,621 | 61,630 | LSC | |

| 33 | (AT)6 | 12 | 63,489 | 63,500 | LSC | |

| 34 | (A)12 | 12 | 68,715 | 68,726 | LSC | |

| 35 | (AT)10 | 20 | 69,266 | 69,285 | LSC | |

| 36 | (T)10 | 10 | 70,716 | 70,725 | LSC | |

| 37 | (A)10 | 10 | 72,600 | 72,609 | LSC | rps18 |

| 38 | (TA)7 | 14 | 74,094 | 74,107 | LSC | rps12 intron |

| 39 | (A)10 | 10 | 74,569 | 74,578 | LSC | clpP intron |

| 40 | (T)11 | 11 | 74,845 | 74,855 | LSC | clpP intron |

| 41 | (T)10 | 10 | 75,108 | 75,117 | LSC | clpP intron |

| 42 | (T)10 | 10 | 75,572 | 75,581 | LSC | clpP intron |

| 43 | (T)10 | 10 | 75,831 | 75,840 | LSC | clpP intron |

| 44 | (A)10 | 10 | 79,177 | 79,186 | LSC | |

| 45 | (AT)6 | 12 | 79,751 | 79,762 | LSC | petB intron |

| 46 | (T)10 | 10 | 86,407 | 86,416 | LSC | rpl16 intron |

| 47 | (T)11 | 11 | 88,970 | 88,980 | IRa | |

| 48 | (T)10 | 10 | 116,573 | 116,582 | IRa | ycf1 |

| 49 | (A)11 | 11 | 120,872 | 120,882 | SSC | |

| 50 | (T)11 | 11 | 121,055 | 121,065 | SSC | |

| 51 | (A)11 | 11 | 128,865 | 128,875 | SSC | ndhA intron |

| 52 | (T)10 | 10 | 129,188 | 129,197 | SSC | ndhA intron |

| 53 | (AT)6 | 12 | 131,778 | 131,789 | SSC | |

| 54 | (T)11 | 11 | 133,103 | 133,113 | SSC | |

| 55 | (T)12 | 12 | 133,236 | 133,247 | SSC | |

| 56 | (T)11 | 11 | 133,374 | 133,384 | SSC | ycf1 |

| 57 | (A)10 | 10 | 135,507 | 135,516 | IRb | ycf1 |

| 58 | (A)11 | 11 | 163,109 | 163,119 | IRb |

Table 5.

Long repeat sequences in A. compactum cp genome

| ID | Repeat start 1 | Type | Size (bp) | Repeat start 2 | Mismatch (bp) | E value | Gene | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3990 | P | 34 | 3996 | − 3 | 4.12E−06 | trnK-UUU (intron) | LSC |

| 2 | 8768 | P | 31 | 48,057 | − 3 | 1.98E−04 | IGS; trnS-GGA | LSC |

| 3 | 10,522 | F | 30 | 39,347 | − 3 | 7.15E−04 | trnG-GCC (intron) | LSC |

| 4 | 31,322 | P | 32 | 31,352 | − 3 | 5.46E−05 | IGS | LSC |

| 5 | 32,991 | F | 30 | 33,020 | − 3 | 7.15E−04 | IGS | LSC |

| 6 | 39,660 | P | 32 | 39,701 | 0 | 4.08E−10 | IGS | LSC |

| 7 | 41,551 | F | 58 | 43,775 | − 3 | 7.54E−20 | psaB; psaA | LSC |

| 8 | 41,595 | F | 37 | 43,819 | − 2 | 2.39E−09 | psaB; psaA | LSC |

| 9 | 63,481 | P | 31 | 126,101 | − 3 | 1.98E−04 | IGS | LSC; SSC |

| 10 | 63,481 | F | 31 | 126,106 | − 3 | 1.98E−04 | IGS | LSC; SSC |

| 11 | 63,487 | F | 32 | 69,264 | − 3 | 5.46E−05 | IGS | LSC |

| 12 | 67,809 | P | 31 | 67,864 | − 2 | 6.83E−06 | IGS | LSC |

| 13 | 71,632 | F | 30 | 71,659 | 0 | 6.53E−09 | IGS | LSC |

| 14 | 72,281 | F | 42 | 72,302 | − 3 | 1.21E−10 | rps18 | LSC |

| 15 | 91,249 | F | 46 | 91,299 | − 1 | 2.10E−16 | trnI-CAU; IGS | IRa |

| 16 | 91,249 | P | 46 | 160,743 | − 1 | 2.10E−16 | trnI-CAU; IGS | IRa; IRb |

| 17 | 91,299 | P | 46 | 160,793 | − 1 | 2.10E−16 | IGS | IRa; IRb |

| 18 | 93,917 | F | 30 | 93,938 | − 3 | 7.15E−04 | ycf2 | IRa |

| 19 | 93,917 | P | 30 | 158,120 | − 3 | 7.15E−04 | ycf2 | IRa; IRb |

| 20 | 93,938 | P | 30 | 158,141 | − 3 | 7.15E−04 | ycf2 | IRa; IRb |

| 21 | 121,695 | P | 30 | 121,723 | − 3 | 7.15E−04 | IGS | SSC |

| 22 | 158,122 | F | 30 | 158,143 | − 3 | 7.15E−04 | ycf2 | IRb |

| 23 | 160,743 | F | 46 | 160,793 | − 1 | 2.10E−16 | IGS | IRb |

| 24 | 160,762 | F | 30 | 160,812 | − 3 | 7.15E−04 | IGS | IRb |

F forward, P palindromic, IGS intergenic space

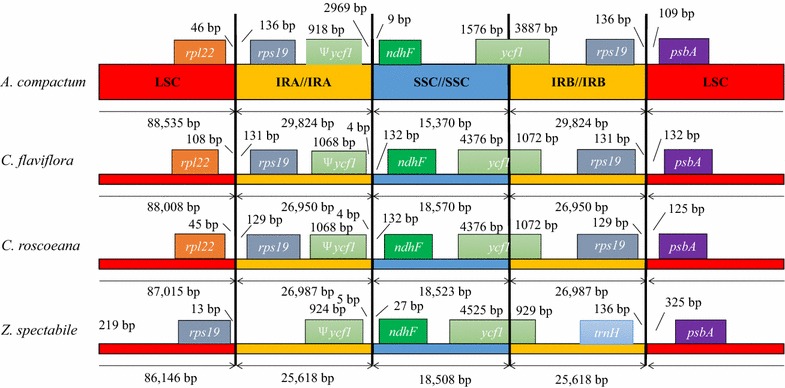

IR expansion/contraction in the A. compactum cp genome

The variations of angiosperm cp genomes in length are mainly because of the contraction and expansion of boundary regions between the IR regions with single copy (SC) regions. A minute comparison of junctional regions between the IR and SC boundaries among A. compactum, C. flaviflora, C. roscoeana, and Z. spectabile is presented in Fig. 2. In addition, a size comparison of cp genome among the four Zingiberaceae species is shown in Additional file 2: Table S1. In spite of the alike lengths of IR regions in these four species (from 25,618 to 29,824 bp), few IR contractions/expansions were still detected. rpl22, ycf1 and rps19 pseudogenes with various lengths were situated in IRb/LSC or IRb/SSC boundaries. The borderline of the IRb/LSC junction was situated in left side of the rps19 gene in examined cp genomes, except in Z. spectabile, which resulted from the contraction of the IRa region in the Z. spectabile cp genome. By contrast, the ycf1 pseudogene was situated in the left side of the IRa-SSC border and was 4–5 bp away from the IRa-SSC borderline, except in the A. compactum cp genome. The size of the ycf1 pseudogene was 918 bp in A. compactum, 1068 bp in C. flaviflora and C. roscoeana, and 924 bp in Z. spectabile. In addition, in the A. compactum cp genome, the ycf1 pseudogene was 2969 bp away from the IRa-SSC borderline, that indicated the expansion of the IR region. The trnH gene was situated in LSC region, except in Z. spectabile cp genome, where it was situated in SSC region and was 136 bp away from the IRb-LSC borderline.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the border positions of the LSC, SSC, and IR regions among four complete Zingiberaceae chloroplast genomes. Gene names are indicated in boxes, and their lengths in the corresponding regions are displayed above the boxes

Comparison with other Zingiberaceae cp genomes

Three sequences representing the Zingiberaceae (C. flaviflora, C. roscoeana and Z. spectabile) were selected for comparison with A. compactum. Pairwise cp genome alignments between A. compactum and other three cp genomes regained a high degree of synteny (Additional file 3: Figure S1, Additional file 4: Figure S1 and Additional file 5: Figure S3). To detect the divergent regions in the cp genome, this study compared the sequence identities among four Zingiberaceae cp genomes by mVISTA, using the annotation of A. compactum as a reference. The multiple sequences alignment showed the coding regions are highly conserved, however the non-coding regions are divergent (Fig. 3). As an example, the intergenic sequences between the trnT-GGU–psbD, rps16–trnQ-UUG, atpH–atpI, trnE-UUC–trnT-GGU, trnT-UGU–trnL-UAA, petA–psbL and psaC–ndhE regions were highly divergent, parts of which have been also reported as divergent sequences in other plant. Obviously, the LSC region and SSC region were more divergent than IR regions.

Fig. 3.

Sequence comparison of the A. compactum, C. flaviflora, C. roscoeana and Z. spectabile cp genomes generated by mVISTA. Black lines designate regions of sequence identity by a 50% identity cutoff with A. compactum. Dashed rectangles indicate highly divergent regions of A. compactum compared with C. flaviflora, C. roscoeana and Z. spectabile

Phylogenetic analysis

Cp genomes are widely employed in the study of evolution through phylogenetics. To examine the phylogenetic position of A. compactum and its relationship within Zingiberales, MP and ML phylogenetical analyses were performed based on 67 protein-coding gene sequences from 15 plant taxa, including A. compactum, as sequenced in the study. The total alignment was 51,452 bp in length. The results are presented in Figs. 4 and 5. The basic topologies were similar in the MP and ML analyses, but there were few differences. Bootstrap values were all extremely high, and nine of the 12 nodes with bootstrap values of ≥ 90% were found in MP tree, whereas eight of 12 nodes were found in ML tree with 100% bootstrap values. The Zingiberaceae species A. compactum, C. flaviflora, C. roscoeana and Z. spectabile were grouped in both MP and ML phylogenetic trees with 100% bootstrap values. In the MP trees, the four Zingiberaceae species composed a unique clade and were separated from the rest of Zingiberales with high bootstrap values in every node. By contrast, the ML tree was mainly separated into two clades, one of which included Strelitziaceae, Heliconiaceae, Musaceae and Lowiaceae species, whereas another included Zingiberaceae, Costaceae, Cannaceae and Marantaceae species. However, the Zingiberaceae and Costaceae species were grouped with a very low bootstrap value (15%) in the ML tree. These phylogenetic results strongly support the position of A. compactum and provide some helpful hints about relationships within the order Zingiberales.

Fig. 4.

MP phylogenetical tree of 15 Zingiberales species, on basis of 67 protein-coding gene sequences in the cp genomes. Bootstrap values are indicated upon the branches

Fig. 5.

ML phylogenetical tree of 15 Zingiberales species, on basis of 67 protein-coding gene sequences in the cp genome. Bootstrap values are indicated upon the branches

Conclusion

The research assembled, annotated and analyzed the whole cp genome of A. compactum, which reveals that the cp genome of A. compactum shares a quadruple structure, gene order, GC content, and codon usage features, similar to those of other land plant cp genomes. This Amomum cp genome was compared with three available Zingiberaceae cp genomes, while the genome structure and composition are similar. Also phylogenetic analysis provides new insight into phyletic evolution of this genus. Our research will contribute to species identification and evolutionary mechanisms required for the further study of A. compactum.

Additional files

Additional file 1. Minimum Standards of Reporting Checklist.

Additional file 2: Table S1. Size comparison of A. compactum cp genomic regions with those of 3 other Zingiberaceae cp genomes.

Additional file 3: Figure S1. Chloroplast genomic alignment between A. compactum and C. flaviflora (KR967361).

Additional file 4: Figure S2. Chloroplast genomic alignment between A. compactum and C. roscoeana (KF601574).

Additional file 5: Figure S3. Chloroplast genomic alignment between A. compactum and Z. spectabile (JX088661).

Authors’ contributions

XL and JX initiated the research, MW and QL drafted the paper and processed the data, XL supervised the task, the above authors analysed the results and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

All authors thank Dr. Shi-Lin Chen for his helps on group discussion and manuscript polishing.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during the course of this study are included in this document or obtained from the appropriate author(s) at reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This work is supported by the grants from the National Key Technology Support Program (2015BAI05B02) and from the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences Special Fund for Thirteen-five key research (ZZ10-007).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- cp

chloroplast

- LSC

large single copy

- SSC

small single copy

- IR

inverted repeat

- tRNA

transfer RNA

- rRNA

ribosomal RNA

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13020-018-0164-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Ming-li Wu, Email: justuswu@163.com.

Qing Li, Email: qli@smmu.edu.cn.

Jiang Xu, Email: jxu@icmm.ac.cn.

Xi-wen Li, Phone: +86-010-8408-4107, Email: xwli@icmm.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Bendich AJ. Circular chloroplast chromosomes: the grand illusion. Plant Cell Online. 2004;16:1661–1666. doi: 10.1105/tpc.160771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chumley TW, Palmer JD, Mower JP, Fourcade HM, Calie PJ, et al. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Pelargonium hortorum: organization and evolution of the largest and most highly rearranged chloroplast genome of land plants. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:2175–2190. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmer JD. Plastid chromosomes: structure and evolution. In: Bogorad L, Vasil I, editors. Cell culture and somatic cell genetics of plants. San Diego: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 5–53. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raubeson LA, Jansen RK. Chloroplast genomes of plants. In: Henry RJ, editor. Plant diversity and evolution: genotypic and phenotypic variation in higher plants. Cambridge: CAB International; 2005. pp. 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jansen RK, Cai Z, Raubeson LA, Daniell H, dePamphilis CW, et al. Analysis of 81 genes from 64 plastid genomes resolves relationships in angiosperms and identifies genome-scale evolutionary patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:19369–19374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709121104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Givnish TJ, Ames M, McNeal JR, McKain MR, Steele PR, et al. Assembling the tree of the monocotyledons: plastome sequence phylogeny and evolution of Poales. Ann Mo Bot Gard. 2010;97:584–616. doi: 10.3417/2010023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Millen RS, Olmstead RG, Adams KL, Palmer JD, Lao NT, et al. Many parallel losses of infA from chloroplast DNA during angiosperm evolution with multiple independent transfers to the nucleus. Plant Cell Online. 2001;13:645–658. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.3.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guisinger M, Chumley T, Kuehl J, Boore J, Jansen R. Implications of the plastid genome sequence of Typha (Typhaceae, Poales) for understanding genome evolution in Poaceae. J Mol Evol. 2010;70:149–166. doi: 10.1007/s00239-009-9317-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Downie SR, Palmer JD. Use of chloroplast DNA rearrangements in reconstructing plant phylogeny. In: Soltis PS, Soltis DE, Doyle JJ, editors. Molecular systematics of plants. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1992. pp. 14–35. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li X-W, Hu Z-G, Lin X-H, Li Q, Gao H-H, Luo G-A, et al. High-throughput pyrosequencing of the complete chloroplast genome of Magnolia officinalis and its application in species identification. Acta Pharm Sin. 2012;47:124–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu C, Shi LC, Zhu YJ, Chen HM, Zhang JH, Lin XH, et al. CpGAVAS, an integrated web server for the annotation, visualization, analysis, and GenBank submission of completely sequenced chloroplast genome sequences. BMC Genom. 2012;13:715. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis SE, Searle SMJ, Harris N, Gibson M, Iyer V, Richter J, et al. Apollo: a sequence annotation editor. Genome Biol. 2002 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-12-research0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:0955–0964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.0955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lohse M, Drechsel O, Kahlau S, Bock R. OrganellarGenomeDRAW—a suite of tools for generating physical maps of plastid and mitochondrial genomes and visualizing expression data sets. Nucl Acids Res. 2013;41(Web Server issue):W575. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurtz S, Choudhuri JV, Ohlebusch E, Schleiermacher C, Stoye J, Giegerich R. REPuter: the manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:4633–4642. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurtz S, Phillippy A, Delcher AL, Smoot M, Shumway M, Antonescu C, et al. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biol. 2004;5:1–9. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-2-r12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayor C, Brudno M, Schwartz JR, Poliakov A, Rubin EM, Frazer KA, et al. VISTA: visualizing global DNA sequence alignments of arbitrary length. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:1046–1047. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.11.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Posada D. jModelTest: phylogenetic model averaging. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25:1253–1256. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swofford DL. PAUP*. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods). Version 4.0b10. Sunderland: Sinauer Associates; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tangphatsornruang S, Sangsrakru D, Chanprasert J, Uthaipaisanwong P, Yoocha T, Jomchai N, et al. The chloroplast genome sequence of mungbean (Vigna radiata) determined by high-throughput pyro-sequencing: structural organization and phylogenetic relationships. DNA Res. 2010;17:1–22. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsp025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qian J, Song J, Gao H, Zhu Y, Xu J, Pang X, et al. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of the medicinal plant Salvia miltiorrhiza. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e57607. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yi D, Kim K. Complete chloroplast genome sequences of important oilseed crop Sesamum indicum L. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e35872. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melotto-Passarin D, Tambarussi E, Dressano K, De Martin V, Carrer H. Characterization of chloroplast DNA microsatellites from Saccharum spp. and related species. Genet Mol Res. 2011;10:2024–2033. doi: 10.4238/vol10-3gmr1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin G, Baurens FC, Cardi C, Aury JM, D’Hont A. The complete chloroplast genome of banana (Musa acuminata, Zingiberales): insight into plastid monocotyledon evolution. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e67350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang Y, Dang YY, Li Q, Lu JJ, Li XW, Wang YT. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of poisonous and medicinal plant Datura stramonium: organizations and implications for genetic engineering. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(11):e110656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Minimum Standards of Reporting Checklist.

Additional file 2: Table S1. Size comparison of A. compactum cp genomic regions with those of 3 other Zingiberaceae cp genomes.

Additional file 3: Figure S1. Chloroplast genomic alignment between A. compactum and C. flaviflora (KR967361).

Additional file 4: Figure S2. Chloroplast genomic alignment between A. compactum and C. roscoeana (KF601574).

Additional file 5: Figure S3. Chloroplast genomic alignment between A. compactum and Z. spectabile (JX088661).

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during the course of this study are included in this document or obtained from the appropriate author(s) at reasonable request.