Abstract

Despite the recent proliferation of price transparency tools, consumer use and awareness of these tools is low. Better strategies to increase the use of price transparency tools are needed. To inform such efforts, we studied who is most likely to use a price transparency tool. We conducted a cross-sectional study of use of the Truven Treatment Cost Calculator among employees at 2 large companies for the 12 months following the introduction of the tool in 2011-2012. We examined frequency of sign-ons and used multivariate logistic regression to identify which demographic and health care factors were associated with greater use of the tool. Among the 70 408 families offered the tool, 7885 (11%) used it at least once and 854 (1%) used it at least 3 times in the study period. Greater use of the tool was associated with younger age, living in a higher income community, and having a higher deductible. Families with moderate annual out-of-pocket medical spending ($1000-$2779) were also more likely to use the tool. Consistent with prior work, we find use of this price transparency tool is low and not sustained over time. Employers and payers need to pursue strategies to increase interest in and engagement with health care price information, particularly among consumers with higher medical spending.

Keywords: price transparency, consumerism, patient engagement, price variation, benefit design

Background

Price transparency tools that allow patients to compare prices of health care services across providers have proliferated in recent years; more than half of states have laws requiring either payers or providers to disclose pricing information1 and many employers and health plans offer their own tools. Prior studies have found that patients who use price transparency tools are more likely to receive lower priced care for select services.2-5 However, recent studies have shown that the promise of price transparency to drive lower spending has not yet been realized. Offering price transparency tools is not associated with lower overall spending primarily because few people with access to such tools use them to shop for lower priced providers.6-8 As such, strategies to increase use of price transparency tools will be an important focus of future work. To inform such efforts, we examined patient and market characteristics to describe who is most likely to use a price transparency tool.

Methods

The Truven Treatment Cost Calculator tool is a Web-based platform on which patients can search for personalized estimates of expected out-of-pocket costs for a range of services across providers in their community. We studied use of this tool among employees at 2 large companies.9 One company introduced the tool on April 1, 2011, and the other on January 1, 2012; we examined use of the tool for the 12 months following introduction by each employer. The employers marketed the tool to their employees via communications during open enrollment including emails and paper mailings, and used small prizes and lotteries to encourage employees to sign up for the tool.

We obtained detailed search log data to describe each search by employees and their dependents, including the date of search and the service searched for. We linked these search data for each family to the family’s insurance claims and enrollment files from the year prior to the introduction of the price transparency tool using the Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database. We conducted analyses at the family level because family members may share an online account and search for services on behalf of other members of their family. Any family in which at least 1 person used the price transparency tool within the study period was categorized as a “user.”

We constructed variables to describe provider supply and price variation for counties and metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs). First, we categorized counties with fewer than three hospitals as low hospital supply counties. Second, we calculated the price variation in an MSA based on the coefficient of variation for the price of office visits and then categorized MSAs into the first (low), second (moderate), or third (high) tertile of price variation. For this price variation metric, we used CPT 99213 as a proxy for all office visits, as this CPT code is the most common evaluation and management CPT code used by physicians. Third, we defined a provider price index for each MSA (see Online Appendix S1 for details), and classified MSAs into tertiles of this price index.

We conducted multivariate logistic regressions at the family level to quantify the association between demographic and health care factors and use of the tool. The model covariates were related to employee demographics (employee age, median income in their zip code, whether they had any covered dependent(s)), provider supply and price in the employee’s area of residence (hospital supply, provider price variation tertile, provider price index tertile), and use of medical care and insurance (whether anyone in the family had a comorbidity, and total medical spending and deducible level prior to the introduction of the price transparency tool). Employees faced the same deductible in the year before and year after the tool was introduced. We did not control for marketing efforts in our multivariate analyses because such efforts affected both users and non-users. We conducted a sensitivity analysis where we removed total medical spending from the multivariate model and instead used an indicator for whether the family had used a “shoppable” health care service in the prior year, as some medical spending is not well suited to shopping in advance of care. We defined shoppable services as lab tests, imaging, outpatient procedures, evaluation and management services, and maternity care.

Results

Among the 70 408 families offered the price transparency tool across the 2 employers, 21% had a deductible less than $500 and 26% had a deductible over $1500 (Table 1). One third (33%) of families were enrolled in preferred provider organization plans and two thirds (67%) were enrolled in high-deductible/consumer-directed health plans.

Table 1.

Price Transparency Tool Use in the First 12 Months (n = 70 408 Families).

| n (%) | Unadjusted use rates (at least one sign-on),a % | Multivariate logistic regression results |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At least 1 sign-on |

3 or more sign-ons |

|||||

| Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval | |||

| Employee age | ||||||

| 18-37 | 18 376 (25.8) | 14.0 | 1.55 | 1.44-1.66 | 1.73 | 1.41-2.13 |

| 38-46 | 18 105 (25.4) | 11.0 | 1.14 | 1.06-1.23 | 0.98 | 0.78-1.24 |

| 47-54 | 17 189 (24.1) | 10.8 | 1.12 | 1.04-1.21 | 1.15 | 0.92-1.43 |

| 55-64 | 17 562 (24.6) | 8.7 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Median income in family’s zip code | ||||||

| $32 708 | 2811 (4.0) | 9.1 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| $42 658 | 6268 (8.9) | 9.3 | 1.03 | 0.88-1.21 | 1.05 | 0.67-1.67 |

| $51 492 | 13 026 (18.5) | 10.3 | 1.15 | 1.01-1.33 | 1.16 | 0.76-1.77 |

| $63 808 | 20 895 (29.7) | 11.6 | 1.29 | 1.13-1.48 | 1.32 | 0.88-1.98 |

| $87 404 | 27 408 (38.9) | 11.9 | 1.24 | 1.08-1.42 | 1.22 | 0.82-1.84 |

| Dependents | ||||||

| No dependent | 32 059 (45.0) | 10.2 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Any dependent | 39 173 (55.0) | 12.0 | 1.17 | 1.10-1.24 | 1.29 | 1.10-1.52 |

| Provider supplyb | ||||||

| Do not reside in a county with low hospital supply | 49 797 (69.9) | 11.2 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Reside in a county with low hospital supply | 21 435 (30.1) | 11.2 | 1.07 | 1.01-1.13 | 1.24 | 1.06-1.44 |

| Area provider price variationc | ||||||

| Low variation | 23 935 (33.6) | 9.8 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Moderate variation | 23 865 (33.5) | 11.3 | 1.21 | 1.14-1.29 | 1.33 | 1.11-1.60 |

| High variation | 23 432 (32.9) | 12.5 | 1.26 | 1.19-1.34 | 1.40 | 1.16-1.67 |

| Area price indexd | ||||||

| Low price index | 24 056 (33.8) | 12.2 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Moderate price index | 27 395 (38.5) | 9.6 | 0.80 | 0.75-0.86 | 0.84 | 0.68-1.03 |

| High price index | 19 781 (22.8) | 12.1 | 1.04 | 0.97-1.11 | 1.11 | 0.91-1.34 |

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| No comorbidity | 62 826 (88.2) | 11.5 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Any comorbidity | 8406 (11.8) | 9.2 | 1.01 | 0.93-1.10 | 1.09 | 0.86-1.39 |

| Total medical spending in the prior year | ||||||

| $0-$999 | 19 043 (26.7) | 10.6 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| $1000-$2779 | 16 536 (23.2) | 12.6 | 1.33 | 1.24-1.43 | 1.39 | 1.14-1.70 |

| $2780-$8000 | 17 700 (24.9) | 11.4 | 1.27 | 1.18-1.36 | 1.27 | 1.03-1.57 |

| >$8000 | 17 953 (25.2) | 10.3 | 1.18 | 1.09-1.27 | 1.02 | 0.81-1.28 |

| Deductible level | ||||||

| <$500 | 14 651 (20.6) | 9.0 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| $500-$999 | 20 043 (28.1) | 8.3 | 0.77 | 0.70-0.84 | 0.34 | 0.26-0.46 |

| $1000-$1499 | 10 735 (15.1) | 10.6 | 0.96 | 0.87-1.07 | 0.60 | 0.45-0.80 |

| $1500+ | 18 768 (26.4) | 15.7 | 1.52 | 1.38-1.67 | 0.93 | 0.72-1.20 |

| Unknown | 7035 (9.9) | 12.9 | 1.36 | 1.23-1.49 | 1.26 | 1.00-1.59 |

All unadjusted rates across demographic subgroups are statistically significant at the P < .001 level within the subgroup except for employees residing in a county with low versus not low hospital supply.

Low provider supply counties have fewer than 3 hospitals.

Area provider price variation is defined as the coefficient of variation (COV) for the price of office visits in the family’s metropolitan statistical area (MSA). Low, moderate, and high variation are tertiles of COV in the sample (low-variation COV = 10.3-22.4, moderate-variation COV = 22.5-26.8, high-variation COV = 26.9-425.3).

The area price index is defined in Online Appendix S1. Low price, moderate price, and high price are tertiles of the price index in the sample (low price index = 0.657-0.967, moderate price index = 0.968-1.008, high price index = 1.009-2.379).

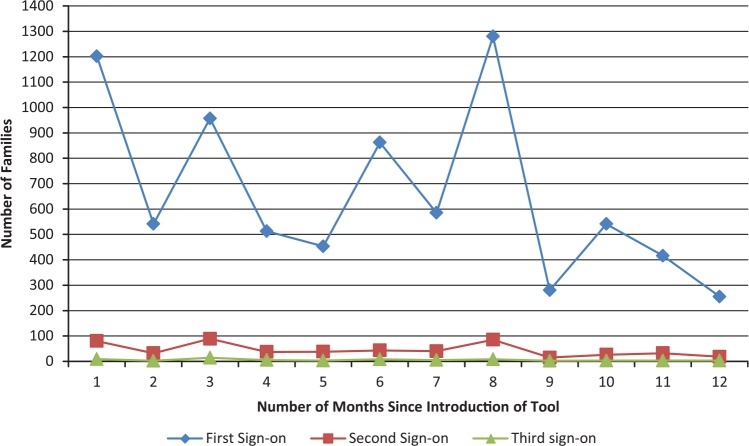

Of families offered the tool, 7885 (11%) used the tool at least once in the 12 months following its launch, and 854 (1%) families used the tool at least 3 times in those 12 months. Of the families who used the tool in the first 12 months, 70% (5542) signed on only once. Figure 1 shows the number of first, second, and third sign-ons to the tool during the study period; each observed spike in sign-ons followed marketing efforts by the employers to increase the use of the tool.

Figure 1.

Month of first, second, and third sign-on to the tool by family.

Use of the tool was more common among families with younger employees, at least 1 dependent, and those living in areas with higher median income (Table 1). Families living in an MSA with greater variation in health care prices, with high deductibles, and with total medical spending greater than $1000 were also more likely to use the tool. A sensitivity analysis that substituted any receipt of a shoppable service for total medical spending in the multivariate model showed similar results (Online Appendix Table S1).

Discussion

Use of this price transparency tool was relatively low and most families who used the tool did so only once. These results echo prior research finding that few people offered price transparency tools use them6-8 and that younger people are more likely to use a price transparency tool.3,8 Recent work found that those who used a transparency tool had higher medical spending than non-users.8 Our findings highlight that this is not a monotonic relationship, and that the highest rate of tool use was among those with moderate spending. We also add to the literature by describing higher rates of tool use in markets with greater price variation.

Our findings suggest several strategies for promoting greater use of price transparency tools. Currently, tool use is higher among groups that are more likely to have Internet fluency, such as younger employees and those from higher income areas. Targeted marketing to groups with lower use rates may be important to improve access to price information across all groups. Our findings support the idea that marketing is effective in increasing tool use, as we observe that marketing is associated with short-term spikes in the use of the tool. However, more prolonged marketing efforts may be needed to remind people of the tool’s availability.

In addition to marketing, other strategies to promote sustained use of price transparency tools are necessary. Although our data cannot explain why most families do not continue to use the tool, prior research has emphasized that improving the clarity and format of information is essential to increasing the use of online provider price and quality data.4,10,11 Increasing the salience of the tool may also be important. Ideally, patients should receive reminders of the availability of the tool at the time they are thinking about selecting a health care provider, for example, when a prior authorization is requested for a patient or when a patient receives an explanation of benefits.

Families with the highest total medical spending were less likely to use the tool than families with moderate spending. Those with high spending often reach their deductibles and maximum out-of-pocket limits, and therefore are likely less price sensitive. Different benefit designs such as reference pricing may be needed to make these higher-spenders more sensitive to price information.

Our analyses have important limitations. We only observe 2 large employers and we do not know what fraction of the sign-ons to the tool represent situations where a consumer was truly shopping for health care services, and not merely making use of other features available on the tool such as learning about their benefit design. In addition, we are not able to observe other variables that may be associated with use of the tool, such as employees’ out-of-pocket maximum limits, and we are missing deductible information for 10% of the sample.

Despite widespread enthusiasm for price transparency to help patients select lower priced providers, our analysis shows that the use of a price transparency tool is low, not sustained over time, and concentrated among consumers who are more price sensitive because they have higher deductibles or live in areas with substantial variation in provider prices.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study was supported by a grant from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation.

References

- 1. de Brantes F, Delbanco S. Report Card on State Price Transparency Laws; 2016. http://www.hci3.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/reportcard2016.pdf.

- 2. Semigran HL, Gourevitch RA, Sinaiko AD, Cowling D, Mehrotra A. Patients’ views on price shopping and price transparency. Am J Manag Care. forthcoming. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Whaley C, Schneider Chafen J, Pinkard S, et al. Association between availability of health service prices and payments for these services. JAMA. 2014;312(16):1670-1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Higgins A, Brainard N, Veselovskiy G. Characterizing health plan price estimator tools: findings from a national survey. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(2):126-131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tu H, Gourevitch R. Moving Markets: Lessons from New Hampshire’s Health Care Price Transparency Experiment. Washington, DC: California Health Care Foundation and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Desai S, Hatfield LA, Hicks AL, Chernew ME, Mehrotra A. Association between availability of a price transparency tool and outpatient spending. JAMA. 2016;315(17):1874-1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mehrotra A, Brannen T, Sinaiko AD. Use patterns of a state health care price transparency web site: what do patients shop for? Inquiry. 2014;(51):1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sinaiko AD, Rosenthal MB. Examining a health care price transparency tool: who uses it, and how they shop for care. Health Aff. 2016;35(4):662-670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Truven Health Analytics. Truven Health Analytics Health Care Cost Transparency Tool Reaches 20 Million User Mark: Treatment Cost Calculator Helps Health Care Consumers Comparison Shop for Best Care. Ann Arbor, MI: Truven Health Analytics; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mehrotra A, Hussey PS, Milstein A, Hibbard JH. Consumers’ and providers’ responses to public cost reports, and how to raise the likelihood of achieving desired results. Health Aff. 2012;31(4):843-851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yegian JM, Dardess P, Shannon M, Carman KL. Engaged patients will need comparative physician-level quality data and information about their out-of-pocket costs. Health Aff. 2013;32(2):328-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.