Abstract

Objectives:

The objective of the study is to study the incidence and pattern of mandible fractures in the holy city of Madinah in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia over a retrospective period of 3 years from 2013 (1434H) to 2016 (1436H) and to compare the results with those from other regions of Saudi Arabia and elsewhere.

Materials and Methods:

Relevant data of patients admitted to the King Fahad Hospital, Madinah with a fracture of the mandible during the study were collected from their medical records and radiographs. The age, gender, etiology, role of the patient, site, and number of fractures in the patients were evaluated. The data were analyzed by standard statistical methods.

Results:

A total of 197 patients with fracture of the mandible were admitted in the period of the study by the Oral Maxillofacial Surgery Department, King Fahad Hospital, Madinah. There were 165 male and 32 female patients. The ages ranged from 3 to 86 years with a mean of 24 years. A total of 260 fractures of Mandible were documented. The largest number (113) of patients was found in the age group between 16 and 30 years. Trauma caused by motor vehicle road traffic accidents (RTAs) was the main etiology of the fractures followed by falls and assault. The majority of the patients were in the role of vehicle drivers. The condylar anatomical site of mandible was most frequently affected and constituted the largest number (103) of fractures followed by the angle (51), parasymphysis (45), and then by the body (23) of the mandible. Dentoalveolar fractures were present in 22 cases. Very less number of coronoid fractures (7), followed by those of the ramus (5), and least number at the symphysis (4) of the mandible were found.

Conclusion:

RTA was the most common etiology for trauma and fracture of the mandible. The males outnumbered the female patients, the largest number of patients with trauma and mandible fracture was found in the age group between 16 and 30 years and frequency of condylar fractures was higher.

Keywords: Behavior, fracture, Madinah, mandible, road traffic accident

INTRODUCTION

Road traffic accidents (RTAs) are the leading cause of all trauma admissions in hospitals worldwide.[1] Saudi Arabia ranks second after Oman among Arab countries and 23rd globally in terms of deaths due to road accidents, accounting for 4.7% of all mortalities compared to 1.7% in the UK and USA.[2,3] Trauma, chiefly due to the RTAs places a huge burden on the health-care service in Saudi Arabia associated with a high morbidity and mortality. The incidence of maxillofacial trauma with fractures of the facial bones is very common and forms a major portion in the workload of an oral and maxillofacial surgeon in this country.

The mandible is particularly more prone for maxillofacial trauma and fractures due to its unique mobility, shape, and chin prominence in the facial skeleton. It is the second most frequent of the facial bones affected by traumatic injuries and shown to account for 15.5%–59% of all facial fractures.[4] The mandible can be seen fractured alone or in combination with a fracture of other bones in the maxillofacial region. A broken lower jaw is accompanied by pain, deranged occlusion and loss of masticatory function, speech impairment, and esthetic disfigurement with psychological effects apart from significant financial cost.[5,6]

The epidemiology of mandible fractures is highly variable with time among several countries. The mechanism of injury or etiology is also inconsistent in the literature. Etiology of fracture is multifactorial and based variably on socioeconomic status, culture, technology, demography, and economic factors.[7]

The purpose of our study was to evaluate the incidence, etiology, and pattern of fractures of the mandible in the Holy city of Madinah over a retrospective period of 3 years from 2013 to 2016 and to compare the results with those from other regions of Saudi Arabia and elsewhere.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a retrospective study of the incidence and pattern of mandible fractures in the Holy city of Madinah over a period of 3 years from 1434H (2013) to 1435H (2016) amongst patients admitted in the King Fahad Hospital, Madinah. The King Fahad Hospital, Madinah is a major referral MOH hospital with 500 beds receiving all trauma cases over a catchment area of 450 km radius.

Relevant data of patients with fracture of the mandible during the study were collected from their medical records and radiographs. The age, sex, etiology, role of the patient, site, and number of fractures in the patients were evaluated.

The data were analyzed by standard statistical methods using SPSS (version 16.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), by applying Chi-square test.

RESULTS

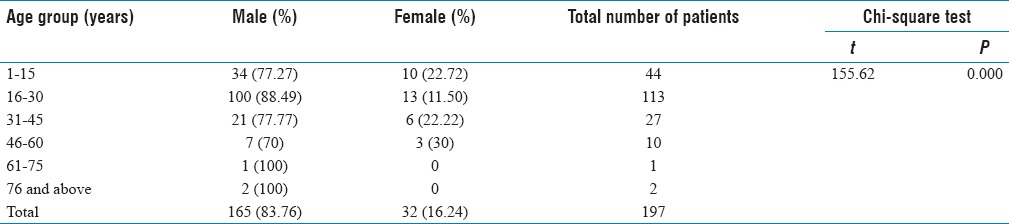

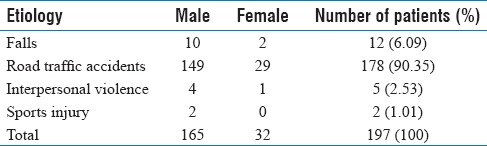

The majority of the patients in this study were males (165) compared to females (32) with a male:female ratio of 5.15:1. A total of 197 patients with fracture of the mandible were admitted in the period of the study with the age of the patients ranging from 3 to 86 years and a mean age of 24 (23.93) years [Table 1]. Trauma caused by RTAs in 178 patients with a frequency of 90.35% was the main etiology of mandible fractures in this study. This was followed by falls in 12 patients (6.09%) and assault or interpersonal violence in five patients (2.53%). Only two patients had sport-related injury [Table 2].

Table 1.

Age and gender distribution of study population

Table 2.

Distribution of the mandibular fractures according to etiology

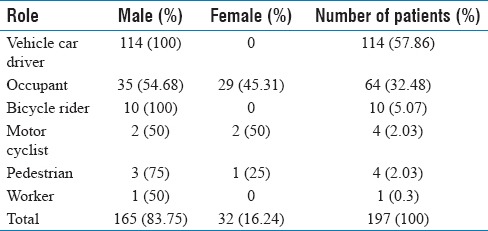

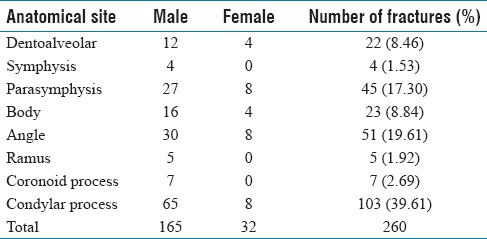

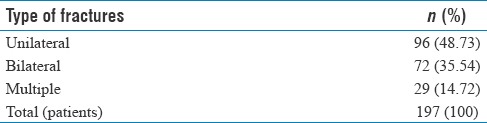

The majority of the patients (114, 57.86%) were motor vehicle (car) drivers and all of them were males. Sixty-four percent or 14.72% of the number of patients were occupants in the vehicle with 35 males and 29 females [Table 3]. The mandibular condyle was the most common site of fracture in this study found in a vast majority of trauma patients (n = 103, 39.61%) involving 95 males and 8 females followed by the mandibular body, angle, and parasymphysis [Table 4]. Majority of patients (n = 96, 48.73%) had unilateral type of mandibular fractures followed by 72 (35.54%) patients with bilateral fractures [Table 5].

Table 3.

Distribution of mandibular fractures according to role

Table 4.

Distribution of mandibular fractures according to location

Table 5.

Distribution of mandibular fractures according to type

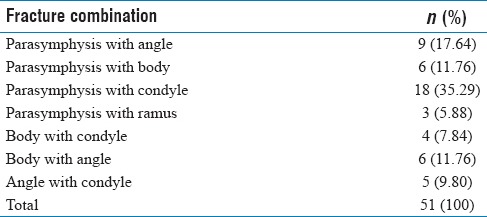

Multiple fractures or fracture in more than two sites were noted in 29 (14.72%) patients. The most common combination of bilateral fractures in our study is condyle with parasymphysis in 18 patients [Table 6].

Table 6.

Combination of mandibular fractures (n=51/260; 19.61%)

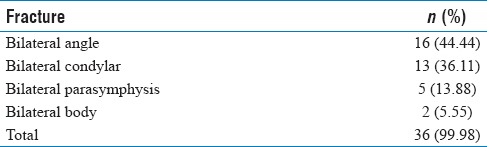

Bilateral and similar site fractures of mandible were found in 36 patients, and most of these were bilateral angle fracture (n = 16; 44.44%) followed by bilateral condylar fractures in 13 patients (36.11%). Five patients had bilateral parasymphysis (13.88%), and two patients (5.55%) had bilateral body fracture of the mandible [Table 7].

Table 7.

Bilateral (similar site) mandibular fractures

DISCUSSION

Our study revealed 260 fractures of the mandible in 197 maxillofacial trauma patients over the retrospective study period of 3 years between 2013 (1432H) and 2016 (1436H).

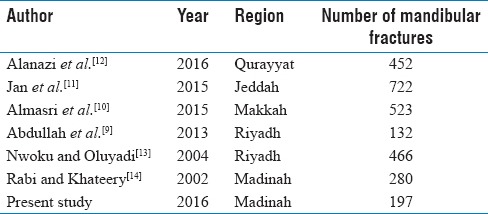

Mandibular fractures have been reported as significantly more common than middle-third facial fractures in many countries.[3,4,5,6,7,8] Variation is noted in the number of fractures of mandible in different regions of Saudi Arabia due to differences in regional factors, sample size, and period of the studies done[9,10,11,12,13,14] [Table 8].

Table 8.

Number of fractures of mandible reported in some regions of Saudi Arabia

A male to female ratio ranging between 2.9:1 and 7.1:1; and above has been reported from many other countries.[5,6,7,8] Studies in some cities of the Kingdom have reported M:F ratio of 4.4:1; in Makkah[10] M:F ratio 6:1 both in Riyadh and Jeddah[9,11] and M:F ratio of 2.1:1; in Qurayyat city.[12] The M:F ratio of 5.15:1, in our study, is similar to that reported earlier in Medina by Rabi and Khateery who found an M:F ratio of 5.2:1[14] However, the M:F ratio found in our study is significantly less than the ratio of 10:1; seen in Aseer[15] a mountainous region of the Kingdom with high risk of RTAs. Males are more frequently liable to be injured than females due to their increased outdoor activity and involvement in interpersonal violence (IPV). In addition, Saudi Arabian women are not permitted to drive by law which explains their lesser number.

The highest number (113) of patients was found in the age group between 16 and 30 years (57.36%) which included 100 males and 13 females. Our finding is in agreement with the earlier 5 years Madinah study of Rabi and Khateery[14] who found the majority of patients with fracture of the mandible in the group aged 21–30 years (33%) and concurs with studies with a similar observation.[7,16,17] This typical age group is considered to comprise young adults and are often described as a risk population for the occurrence of mandibular fractures.[7] Few studies also found the age group 16–35 years to be commonly involved in accidents and occurrence of fracture which is closer to our finding.[13,18,19] Totally, 140 patients in the present study were between 16 and 45 years and formed a significantly huge number (71%) of patients with trauma and fracture of mandible in concurrence with a study in Makkah.[10] This implies a need to target and motivate this vulnerable and “at risk” age group toward safer driving.

Forty-four patients (22.33%) in the group of 1–15 years had fracture of the mandible. Sakr et al.,[20] quote a higher incidence of fracture in children in the first decade of age. Ten (5.07%) patients were between 46 and 60 years of age. Only one patient was seen in the age group of 61–75 years and two were above 76 years. A restricted sedentary lifestyle may explain less RTA-related trauma in elderly individuals.

Our finding of RTA as the main etiology of maxillofacial injuries with mandible fractures is in agreement with several studies done in developing countries including KSA and UAE.[9,10,21,22,23] Few others have found motorcycle accidents to be a major cause of mandible fractures.[24,25]

The very high frequency of RTA and related fracture of mandible is not surprising because, Saudi Arabia is ranked 23rd in the world on the list of countries having highest death rates in road accidents among high-income states (accident to death ratio is 32:1 vs. 283:1 in USA), and RTA is considered to be the country's main cause of death for 16–30-year-old males. Road injuries are reported to be the most serious in this country with an accident to injury ratio of 8:6, compared with the international ratio of 8:1. The rate of RTA caused by 4-wheeled vehicles in Saudi Arabia is the highest of all worldwide accidents.[3,26,27]

In this study, a history of fall was given by 12 patients (6.09%) which is the second but a much less frequent cause than RTA for mandible fracture in Madinah. This is in agreement with Harshitha et al.,[28] whereas in a Turkish study, falls were the main cause of mandible fracture.[29] In Madinah, falls from bicycles, motorcycles, desert bikes, and falls from staircase or escalators in shopping malls were some of the reasons given.

Assault or interpersonal violence was reported in only 2.5% of patients in this study with a fracture of the mandible. This is in total contrast with studies that have shown assault or IPV as the most common cause of maxillofacial injuries including mandibular fractures in many countries of the developed Western world.[26,30,31,32] as well as in Australia and New Zealand.[33,34] Very high assault rates of 72.5% in Sydney, Australia and 74% in Manchester, United Kingdom have been documented by Rix et al. and Asadi and Asadi.[35,36] Compared to RTA in urban areas, assault is recognized as the main cause of mandibular fractures in rural population.[4,33,37] Alcohol and drug consumption, behavioral problems, stress, socioeconomic conditions, political, racial and cultural provocations, or domestic squabbles are several reasons cited for increased IPV or assault across the globe.[38]

The conservative nature of Saudi society and family values, strict punitive laws for assault, and fear of job loss in expatriates occasionally results in prehospital compromise between individuals and causes under-reporting of an alleged assault at the time of hospital admission.

Ten bicyclists and four motorcyclists suffered fracture of the mandible due to direct trauma by falls from the bicycle or motorcycle. The males were mostly hurt by falling from the motorcycle while trying to perform “stunts” or “drag racing” on the roads whereas two female patients were injured during joy riding on a desert motorbike. Four of the patients with fracture of mandible were pedestrians, and one worker sustained occupation tool-related trauma.

In a study, the drivers' knowledge regarding road traffic rules and risks did not match their behavior, and it was found that fatal and nonfatal injuries are significantly determined by speeding, particularly at daytime, and head-on collision to affect the magnitude of the accident.[38] Excessive speed, improper turning, traffic violations, tire failure, fatigue with lack of sleep, and hypoglycemia were some causes attributed for the accidents.[39] However, driver error was found to be the main contributing factor in approximately two-thirds of all RTAs.[40]

Our finding is in agreement with a high frequency of condylar fractures found by Jan et al.,[11] in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Studies from other countries done by Bereket et al.,[29] Schön et al.,[41] de Matos et al.,[42] and Van Beek and Merkx[43] have also found condyle to be the most frequently affected site. While RTA was the main etiology of the condylar fractures in our study, fall and assault have been found to be most commonly associated with condylar fractures by others.[22,44,45] Few studies have reported the condyle as being the second most frequently fractured site location after the symphysis and parasymphysis areas.[6,14] Our finding differs from some regions of Saudi Arabia and other countries where the body of mandible was found to be the most common mandibular fracture site location.[14,16,24,47]

Kheirallah and Almeshaly[48] in an epidemiological analysis of mandibular fractures in KSA over 25 years from 1991 to 2016 found three studies from KSA and eleven from other countries which had discussed the location of mandibular fractures. Their analysis reveals that condyle of the mandible was the most common fracture site not only in Jeddah but also cumulatively from the three studies in KSA. The second most common fracture site seen in their analysis were of the body, and then the angle in KSA and the major etiology of facial fractures was due to RTA. In contrast to their finding in studies from Saudi Arabia, the authors found the body of mandible to be the most common fracture site followed by fracture of condylar process in other countries, where the etiology also unlike in Saudi Arabia was commonly due to assault, not RTA.

Several studies have reported parasymphysis as the most affected site of fracture in the mandible.[12,24,25,28,30] Elgehani and Orafi[16] noted that the most common site of fracture was the parasymphysis, followed by angle of the mandible. Few authors reveal the most common site of fracture being parasymphysis followed by body, angle, and condyle of the mandible.[35] Parasymphysis as the most common site of fracture followed by that of condyle has also been reported.[44,49]

In our study, angle fracture was the second more frequent site of mandible fracture. The angle of the mandible as the most frequent site fracture has been reported in Riyadh[13,20] and other countries.[50]

Studies from different countries show wide variation in the location of the fracture site in the mandible. Differences in regional and patient factors, etiology and mechanism of injury may be some of the contributing causes for the variation.[46]

The most common combination of bilateral fractures in our study is condyle with parasymphysis in 18 patients. This is in agreement with a Turkish study.[34] A horizontally directed impact to the parasymphysis is believed to cause a concentration of tensile strain at the condylar neck resulting in a condylar fracture. Our observation is contrary to Dongas and Hall[37] who reported parasymphysis with angle and Ogundare et al.,[21] who found body with angle as the most frequent mandibular fracture combination.

The strength of this study is that, these observations contribute the additional data to the existing literature and update the knowledge of the researchers regarding the incidence, etiology, and pattern of fractures of the mandible.

The present study has the limitation, that only a restricted number of patients were included and the data were collected from a single center; thus the observations of this study cannot be generalized. As this is a retrospective study the original data could not document in a standardized pattern.

Future research directions

Further studies in large population with standardized documentation as well as categorization of causes for analytic purposes are advised.

CONCLUSION

Motor vehicle RTA was the most common etiology of mandibular fractures in Madinah followed by fall and assault

Majority of the victims were Saudi nationals and in the role of vehicle drivers. Most of the patients were males with a M:F ratio of 5.15:1

Highest number of patients was found in the age group of 16–30 years, recognizable as a risk group

Our study found the condylar region to be the most common anatomical site of mandible fractured followed by the body, angle, and parasymphysis

The most frequent combination of bilateral mandibular fractures was condyle with parasymphysis. Bilateral same site fracture was seen more at the angle

The results of this retrospective study show similarity with some studies and differ with those of several others.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yildirgan K, Zahir E, Sharafi S, Ahmad S, Schaller B, Ricklin ME, et al. Mandibular Fractures Admitted to the Emergency Department: Data analysis from a swiss level one trauma centre. Emerg Med Int. 2016;2016:3502902. doi: 10.1155/2016/3502902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Co-operation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf (GCC). Statistics Department. 2012. [Last cited on 2014 Feb 16]. Available from: http://www.gcc.ag.org/eng/

- 3.World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Road Safety. Geneva, CH: World Health Organization; 2013. [Last accessed on 2016 Dec 22]. Available from: http://www.who.igd/violence_injuryprevention/roadsafetystatus/2013/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellis E, 3rd, Moos KF, el-Attar A. Ten years of mandibular fractures: An analysis of 2,137 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1985;59:120–9. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(85)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Down KE, Boot DA, Gorman DF. Maxillofacial and associated injuries in severely traumatized patients: Implications of a regional survey. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;24:409–12. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(05)80469-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou H, Lv K, Yang R, Li Z, Li Z. Mechanics in the production of mandibular fractures: A clinical, retrospective case-control study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149553. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zix JA, Schaller B, Lieger O, Saulacic N, Thorén H, Iizuka T. Incidence, aetiology and pattern of mandibular fractures in central Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2011;141:w13207. doi: 10.4414/smw.2011.13207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al Ahmed HE, Jaber MA, Abu Fanas SH, Karas M. The pattern of maxillofacial fractures in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates: A review of 230 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;98:166–70. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdullah WA, Al-Mutairi K, Al-Ali Y, Al-Soghier A, Al-Shnwani A. Patterns and etiology of maxillofacial fractures in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Dent J. 2013;25:33–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Almasri M, Amin D, AboOla A, Shargawi J. Maxillofacial fractures in Makka city in Saudi Arabia; an 8-year review of practice. Am J Public Health Res. 2015;3:56–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jan AM, Alsehaimy M, Al-Sebaei M, Jadu FM. A retrospective study of the epidemiology of maxillofacial trauma in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J Am Sci. 2015;11:57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alanazi YM, Latif K, Alrwuili MR, Salfiti F, Bilal M, Wyse KR, et al. Incidence of maxillofacial injuries reported in Al-Qurayyat General Hospital over a period of 3 years. Prensa Med Argent. 2016;102:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nwoku AL, Oluyadi BA. Retrospective analysis of 1206 maxillofacial fractures in an urban Saudi hospital: 8 year review. Pak Oral Dent J. 2004;24:13–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabi AG, Khateery SM. Maxillofacial trauma in al Madina region of Saudi Arabia: A 5-year retrospective study. Asian J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;14:10–4. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Almasri M. Severity and causality of maxillofacial trauma in the Southern region of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Dent J. 2013;25:107–10. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elgehani RA, Orafi MI. Incidence of mandibular fractures in eastern part of Libya. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009;14:e529–32. doi: 10.4317/medoral.14.e529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bataineh AB. Etiology and incidence of maxillofacial fractures in the north of Jordan. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;86:31–5. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogundare BO, Bonnick A, Bayley N. Pattern of mandibular fractures in an urban major trauma center. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:713–8. doi: 10.1053/joms.2003.50118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simsek S, Simsek B, Abubaker AO, Laskin DM. A comparative study of mandibular fractures in the United States and Turkey. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;36:395–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakr K, Farag IA, Zeitoun IM. Review of 509 mandibular fractures treated at the University Hospital, Alexandria, Egypt. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;44:107–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogundare BO, Bonnick A, Bayley N. Pattern of mandibular fractures in an urban major trauma center. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:713–8. doi: 10.1053/joms.2003.50118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee KH. Epidemiology of mandibular fractures in a tertiary trauma centre. Emerg Med J. 2008;25:565–8. doi: 10.1136/emj.2007.055236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al-Khateeb T, Abdullah FM. Craniomaxillofacial injuries in the United Arab Emirates: A retrospective study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:1094–101. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atanasov DT. A retrospective study of 3326 mandibular fractures in 2252 patients. Folia Med (Plovdiv) 2003;45:38–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong KH. Mandible fractures: A 3-year retrospective study of cases seen in an oral surgical unit in Singapore. Singapore Dent J. 2000;23(1 Suppl):6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ansari S, Akhdar F, Mandoorah M, Moutaery K. Causes and effects of road traffic accidents in Saudi Arabia. Public Health. 2000;114:37–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ph.1900610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al Turki YA. How can Saudi Arabia use the Decade of Action for Road Safety to catalyse road traffic injury prevention policy and interventions? Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2014;21:397–402. doi: 10.1080/17457300.2013.833943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harshitha KR, Reddy MP, Srinath KS. Etiology and pattern of mandibular fracture in and around Kolar: A retrospective study. Int J Appl Res. 2016;2:562–5. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bereket C, Sener I, Senel E, Özkan N, Yilmaz N. Incidence of mandibular fractures in black sea region of Turkey. J Clin Exp Dent. 2015;7:e410–3. doi: 10.4317/jced.52169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ström C, Nordenram A, Fischer K. Jaw fractures in the County of Kopparberg and Stockholm 1979-1988. A retrospective comparative study of frequency and cause with special reference to assault. Swed Dent J. 1991;15:285–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Layton S, Dickenson AJ, Norris S. Maxillofacial fractures: A study of recurrent victims. Injury. 1994;25:523–5. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(94)90094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kheirallah M, Matenko D. The epidemiological analysis of mandibular fractures in the material of I Department of Maxillofacial Surgery of Warsaw University in the years 1988-1992. Czas Stomatol. 1994;2:123–9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edwards TJ, David DJ, Simpson DA, Abbott AA. Patterns of mandibular fractures in Adelaide, South Australia. Aust N Z J Surg. 1994;64:307–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1994.tb02216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dongas P, Hall GM. Mandibular fracture patterns in Tasmania, Australia. Aust Dent J. 2002;47:131–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2002.tb00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rix L, Stevenson AR, Punnia-Moorthy A. An analysis of 80 cases of mandibular fractures treated with miniplate osteosynthesis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;20:337–41. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(05)80261-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asadi SG, Asadi Z. The aetiology of mandibular fractures at an urban centre. J R Soc Health. 1997;117:164–7. doi: 10.1177/146642409711700308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dongas P, Hall GM. Mandibular fracture patterns in Tasmania, Australia.Australian Dental Journal. 2002;47:131–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2002.tb00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hassan HM, Al-Faleh H. Exploring the risk factors associated with the size and severity of roadway crashes in Riyadh. J Safety Res. 2013;47:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahmed AA. Hypoglycemia and safe driving. Ann Saudi Med. 2010;30:464–7. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.72268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nofal FH, Saeed AA. Seasonal variation and weather effects on road traffic accidents in Riyadh city. Public Health. 1997;111:51–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.ph.1900297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schön R, Roveda SI, Carter B. Mandibular fractures in Townsville, Australia: Incidence, aetiology and treatment using the 2.0 AO/ASIF miniplate system. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;39:145–8. doi: 10.1054/bjom.2000.0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Matos FP, Arnez MF, Sverzut CE, Trivellato AE. A retrospective study of mandibular fracture in a 40-month period. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39:10–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Beek GJ, Merkx CA. Changes in the pattern of fractures of the maxillofacial skeleton. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;28:424–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0020.1999.280605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.King RE, Scianna JM, Petruzzelli GJ. Mandible fracture patterns: A suburban trauma center experience. Am J Otolaryngol. 2004;25:301–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malik S, Singh G. Incidence, aetiology and pattern of mandible fractures in Sonepat, Haryana (India) Int J Med Dent. 2014;4:51–9. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Motamedi MH, Dadgar E, Ebrahimi A, Shirani G, Haghighat A, Jamalpour MR. Pattern of maxillofacial fractures: A 5-year analysis of 8,818 patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77:630–4. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kadkhodaie MH. Three-year review of facial fractures at a teaching hospital in northern Iran. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;44:229–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2005.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kheirallah M, Almeshaly H. Epidemiological Analysis of Mandibular Fractures in KSA. Conference Paper. 2016. [Last accessed on 2016 Dec 16]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303389924 .

- 49.Natu SS, Pradhan H, Gupta H, Alam S, Gupta S, Pradhan R, et al. An epidemiological study on pattern and incidence of mandibular fractures. Plast Surg Int. 2012;2012:834364. doi: 10.1155/2012/834364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chalya PL, Mchembe M, Mabula JB, Kanumba ES, Gilyoma JM. Etiological spectrum, injury characteristics and treatment outcome of maxillofacial injuries in a Tanzanian Teaching Hospital. J Trauma Manag Outcomes. 2011;5:7. doi: 10.1186/1752-2897-5-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]