Abstract

Purpose of Review

This review describes recent literature on novel ways technology is used for assessment of illicit drug use and HIV risk behaviors, suggestions for optimizing intervention acceptability, and recently completed and ongoing technology-based interventions for drug-using persons at risk for HIV and others with high rates of drug use and HIV risk behavior.

Recent Findings

Among studies (n=5) comparing technology-based to traditional assessment methods, those using Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) had high rates of reported drug use and high concordance with traditional assessment methods. The two recent studies assessing the acceptability of mHealth approaches overall demonstrate high interest in these approaches. Current or in-progress technology-based interventions (n=8) are delivered using mobile apps (n=5), SMS (n=2), and computers (n=1). Most intervention studies are in progress or do not report intervention outcomes; the results from one efficacy trial showed significantly higher HIV testing rates among persons in need of drug treatment.

Summary

Studies are needed to continually assess technology adoption and intervention preferences among drug-using populations to ensure that interventions are appropriately matched to users. Large-scale technology-based interventions trials to assess the efficacy of these approaches, as well as the impact of individual intervention components, on drug use and other high-risk behaviors are recommended.

Keywords: Illicit, drug use, mHealth, intervention, EMA

Introduction

Illicit drug use is consistently and strongly associated with increased risk for HIV, Hepatitis C (HCV), and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) [1–3]. Drug use potentiates HIV risk directly through blood exchange that may occur during injection drug use or indirectly through processes (e.g., disinhibition) operating within sexual encounters involving injection and non-injection drug use [4, 5]. Addressing illicit drug-related HIV risk entails either reducing or regulating drug use through a combination of medical intervention (e.g., naltrexone, methadone maintenance therapy) and behavioral supports (e.g., individual or group therapies). These interventions, often delivered in-person, can be costly and hard to deliver to hidden or stigmatized drug using populations. Likewise, in-person access to these interventions can be restrictive with respect to the time and location of their delivery. Researchers have sought to overcome these challenges through technology-based methods.

mHealth (i.e., mobile health technologies that leverage mobile apps and text [SMS] messaging) and other technologies open new opportunities for both assessment of drug use and intervention delivery through a growing number of devices (e.g., laptops, tablets, mobile phones) and channels (e.g., online, mobile apps, SMS, and social networking platforms). Novel technology-based methods to assess drug use and its correlates are used to inform risk reduction interventions. Online surveys are widely used to assess drug use and HIV risk among at-risk groups. For example, the most recent cycle of the American Men’s Internet Survey (AMIS; n=10,217) [6] showed that 25% of HIV-positive and 23% of HIV-negative/unknown serostatus men who have sex with men (MSM) used marijuana in the past 12 months. A higher percentage of HIV-positive MSM (28.59%) used illicit substances in the past year than HIV-negative/unknown serostatus men (17.51%). High rates of substance use has been shown in other samples of MSM recruited online in the US [7], Europe [8, 9], and Australia [10]. While online surveys are widely used to quantify drug use over a specified period of time (e.g., past month) among high-risk groups, they may yield inaccurate estimates due to recall bias [11]. Newer technology-based assessment methods provide real-time data collection of drug use patterns and their intrapersonal, social, and environmental contextual factors [12]. These methods, referred to as “Ecological Momentary Assessment” (or EMA), collect repeated measures of participants’ behaviors (as well as cognitive, emotional, and environmental factors) as they occur in real time [11]. EMA has been utilized with high rates of participant compliance to identify factors associated with drug use and drug craving, as well as the association between drug use and utilization of healthcare services [13–15].

Much is still unknown about best practices for using technology-based interventions to reach and intervene with drug users. Questions persist about the feasibility of delivering technology-based interventions to drug users since some studies have shown low technology adoption and interest among in drug-using samples. A study of 845 current or former injection drug users (IDUs) (Mean age = 51 years; 89% African American, 65% male, 35% HIV-positive) in Baltimore, Maryland showed that while most participants had a cell phone (86%), lifetime internet use was low (40%) and less than half (42%) were interested in receiving health information via phone or internet [16]. However, in an online-recruited sample of HIV-positive MSM (Mean age = 42; 71% white) in the United Sates (US), over 90% of stimulant-using respondents (n=41/44) had access to a mobile phone (including 21 having access to a smartphone), and 82% (n=36) reported weekly use of a social networking site (e.g., Facebook) [17]. Another study used latent class analysis to define patterns of mobile technology use among of IDUs [18]. Results showed that high mobile technology users, compared to low users, were more likely to inject methamphetamines. These studies suggest that appropriate targets for intervention may vary by drug type and sociodemographic characteristics of users.

There is growing interest in using technology to address HIV and STI risk among injecting and non-injecting drug users. Below we review selected recent literature on novel ways technology is being used to assess illicit drug use, suggestions for optimizing intervention acceptability, and recently completed and ongoing technology-based interventions for drug-using persons at risk for HIV and others with high rates of drug use and HIV risk behavior.

Methods

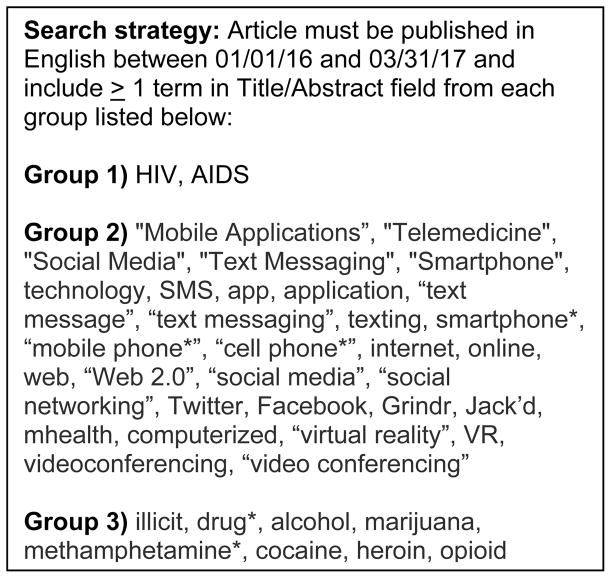

We searched PubMed for studies published between January 1, 2016 and March 31, 2017 using the search strategy outlined in Figure 1. Abstracts from 175 publications were reviewed for relevance; abstract review reduced the number of articles for inclusion to 42. The full article of those 42 publications were retrieved and reviewed for inclusion in this paper. An additional 5 articles [19–23] were identified through references lists and author searchers and included in this review.

Figure 1.

Article search strategy

We focus the discussion below on publications that compared technology-based methods for assessing illicit drug use, beliefs and suggestions from drug-using samples for improving the acceptability of technology-based interventions, and technology-based interventions specifically tailored to drug-using populations. After review of potential articles for inclusion, we did not focus on alcohol use/misuse since few recent studies focused solely on alcohol use [24–27], and none informed the primary purposes for this review.

Comparing technology-based approaches to assess drug use

Five studies examined novel assessment methods for drug use in cohorts of HIV-positive adults[22, 28], as well as those at risk for HIV-infection including IV drug users[21] and MSM [29, 30] (Table 1). Three of those compared the use of computerized technologies to more traditional methods (e.g., Timeline Follow-back [TLFB] assessment) for measuring illicit drug use [21, 28, 29]. Among a cohort of 240 HIV-positive patients in New York City initiating a trial to reduce drug use, agreement on previous 30-day primary drug use assessed at baseline was high between self-administered computerized questionnaires (A-CASI) and the TLFB methods, with higher self-reported drug use in the A-CASI method compared to TLFB [28]. Using self-reported data from 30 MSM, a comparison between previous day assessment of EMA text-messages and a 14-day recall A-CASI survey found higher self-reported frequency of methamphetamine use through EMA (20% vs. 11%) [29]. Similarly, agreement between self-reported EMA measures of heroin and cocaine use was compared to biological measures as well as an A-CASI questionnaire of heroin and cocaine use among 109 participants with a history of intravenous drug use [21]. Agreement between EMA, biological and A-CASI methods (PharmChek) for cocaine (70% with biological; 77% with A-CASI) and heroin use (72% with biological; 79% with A-CASI) were high.

Table 1.

Studies Comparing Technology-based Methods to Assess Illicit Drug Use, January 2016 – March 2017

| Study Authors / Parent Study Name | Study Population and N | Study Objectives | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linas et al (2016) [21]; Exposure Assessment in Current Time (EXACT) | Individuals with a history of intravenous drug use in Baltimore, Maryland who were enrolled in the AIDS Linked to the IntraVenous Experience (ALIVE) study 109 participants; Prevalence of HIV infection: 59% (n=64) |

Agreement between self-reported real-time use of cocaine and/or heroin to A-CASI and biological methods (PharmChek) over the previous 30 days. | High agreement between EMA and two measures of frequently utilized measures of illicit drug-use were found: EMA and A-CASI Agreement Cocaine Use: 77% Heroin Use: 79% EMA and PharmChek Cocaine Use: 70% Heroin Use: 72% |

| Przybyla et al (2016) [22] | HIV positive individuals in Western New York with alcohol use (≥2 days) and ART nonadherence (≥1) in the previous week 27 participants |

Assess feasibility of using app-based collection of substance use (marijuana) and adherence to ART over 2 weeks | Overall, high retention (n=26; 96%) was found among participants, and among those retained, compliance to daily reports was high (95.3%). The majority of participants were given a study-issued smartphone (n=14), while eight (31%) preferred to use their own smartphone. Participants found the daily reporting as moderately / very helpful (92%) and easy to use (84%). |

| Delker et al (2016) [28]; HealthCall | HIV-infected patients from two large HIV primary care clinics in New York City, New York. 233 participants |

Agreement between interviewer-administered Time Line Follow-Back (TLFB) and self-administered computerized questions (A-CASI) on primary drug use frequency in the previous 30 days. | Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) between TLFB and A-CASI was high (ICC = 0.80). Participants reported higher primary drug use days in the previous 30 days in A-CASI compared to TLFB (10.0 vs 8.72). Female gender, younger age, and non-Hispanic ethnicity was found to associated with increased self-reported primary drug use in A-CASI compared to TLFB. |

| Rowe et al (2016) [29]; Intermittent Naltrexone Among Polysubstance Users (Project iN) | Self-reported MSM who reported active meth use and binge-drinking living in San Francisco, CA. 30 participants; Prevalence of HIV infection: 40% (n = 12)[53] |

Secondary analysis on concordance between EMA text messages responses and 14-day recall from audio computer-assisted self-interviews (A-CASI) on self-reported methamphetamine use, alcohol use, and binge alcohol use over 2 months. | Compared to A-CASI, self-reported methamphetamine use (20% vs 11%, p<0.001) and alcohol use (40% vs 35%; p = 0.001) were reported more frequently through daily EMA text messages. |

| Smiley et al (2017) [30]; | African American gay and bisexual men aged 21 to 25 in the Washington DC metro area 25 participants; No HIV prevalence data reported |

Assess feasibility of using EMA text-message (3 times per day) over 2 weeks to collect frequency of sexting, marijuana and alcohol use. | Overall, moderate retention (n = 18; 72%) was found among participants, including 5 participants with scheduling errors resulting in < 14 days of data collection, 1 participant with a lost phone, and 1 responded to no EMA surveys. Average number of days of observation was 10.64. Among all prompted surveys via text-message, compliance was 57.3%. Total time from survey prompt to survey completion was 6.1 minutes. |

Two additional analyses evaluated the feasibility and acceptability of using text-messages and EMA-based approaches to assess marijuana use and alcohol use over two weeks [22, 30]. One study evaluated text message prompts three times per day in a cohort of African American MSM [30], whereas the other study utilized one text-message to prompt participants to open an “app” and complete questions about the previous 24 hours in a cohort of HIV-infected adults [22]. In both cohorts, retention was found to be moderate to high (72% and 96%, respectively). However, completion was higher over the two-week period in the study with once daily prompts (95.3%) compared to thrice daily prompts (57.3%). Both studies found that it took participants less than 10 minutes to complete the surveys [22, 30].

Acceptability and preferences of illicit drugs users for technology-based Interventions

Understanding best approaches to optimize technology-based interventions for drug-using populations is critical to tailor intervention components that are relevant and engaging. Two recent studies examined issues of acceptability of mHealth intervention approaches [31, 32]. Shretha and colleagues [31] surveyed 400 high-risk HIV-negative persons (Mean age = 41; 59% male; 63% white; 87% heterosexual; 73% high school graduates) at a methadone clinic in New Haven, Connecticut to assess current ownership and utilization of communication technology and acceptability of future mHealth approaches. Over 90% of participants owned or had access to a cell phone, of whom 63% owned or had access to a smartphone. Interest in and acceptability of future mHealth intervention approaches was high. Almost three-quarters (72%) were interested in medication reminders, particularly in the form of text messages. Similarly, a majority of participants were interested in receiving information about HIV (66%), mHealth assessments of drug use behaviors (72%), and mHealth assessments of sexual behaviors (65%).

Horvath et al. [32] conducted four focus groups (n=26 participants) of stimulant-using HIV-positive MSM (Mean age = 41 years; 96% White; 42% at least weekly stimulant use) in San Francisco, California and Minneapolis, Minnesota to understand the features and functions of smartphone apps that participants would find most engaging. Men stated that apps that they are most likely to download and keep using over time are those that give them control over its features, and are useful, easy to use, colorful, interactive, credible and secure. Men in this study were enthusiastic about apps that connected them with peers, provided local resources, and synced with their medical record. Men had mixed perspectives about daily medication dose reminders, although most expressed interest in receiving a summary graph of their adherence performance over time to take to their medical appointments. Participants recommended using humor to provide feedback after a missed dose to avoid paternalistic or shaming language.

Technology-based interventions for drug-using persons living with or at risk for HIV and STIs

Characteristics of eight recent, in-progress or completed technology-based interventions are shown in Table 2 [19, 20, 23, 33–37]. Seven of the intervention studies are being conducted in the US [19, 20, 23, 33–35, 37], and one in Canada [36]. Three of the studies reported trial outcomes [20, 23, 35], two of which are pilot trials with small sample sizes [20, 23], and one is a larger-scale efficacy trial [35]. The interventions represented five mobile app interventions, two SMS interventions, and one computer-based interventions.

Table 2.

Studies of Technology-based Interventions for High-risk Drug Users, January 2016 – March 2017

| Study Authors/Intervention Name | Study population | Intervention Technologies & Component(s) | Primary Intervention Target | Study Design and N | Intervention Acceptability & Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Westergaard et al. (2017) [19] mPeer2Peer |

HIV-positive adult patients at a HIV clinic, with VL > 1000 copies/mL, 0 clinic visits in the past 6 months, and who were willing to attend a care visit after enrollment; The original criteria of having a substance use disorder was dropped mid-study due to recruitment difficulty. | Mobile application; Based on the IMB model, and consisting of 2 main components: 1) a mobile app with HIV medical care appointments and adherence reminders, laboratory results, clinic contact information, and twice-daily EMA surveys; and 2) supportive peer navigators who communicated with participants in-person and by telephone and text messaging. | Improve HIV healthcare engagement | RCT of 19 patients to receive either mPeer2Peer or SOC; 12 participants participated in follow up qualitative interviews reported in this study. | Only intervention acceptability reported; Participants reported that the mobile app was easy or very easy to use, noting that the frequent medication and appointment reminders, as well as the EMA surveys, helped them to prioritize their healthcare even during chaotic or stressful times. |

| Guarino et al. (2016) [20]; Check-in Program |

Methadone Maintenance Therapy (MMT) Clients in New York City, NY, USA | Mobile application; Functional Analysis and Self-Management Modules | Skills acquisition; illicit drug use | Single arm study of 25 men, who received a reduced SOC treatment + web-based Therapeutic Education System (TES) + Check-in Program. Results compared to prior collected data on MMT SOC. | 92% accessed the app at least once; 36% required additional training on how to use the mobile device; High levels of module completion; moderate to high acceptability ratings; higher mean weeks opioid abstinent by urine toxicology (Check-in Program = 4.88 weeks vs MMT SOC = 2.72 weeks) |

| Himelhoch et al. (2017) [23]; Heart2HAART |

HIV-positive adults (18–64) who attend an adherence program in Baltimore, MD, USA with a lifetime history of alcohol or drug use with adherence difficulties | Mobile application to assist with ART adherence among HIV-positive substance users also receiving directly observed treatment; participants responded to randomly selected daily messages about their medication regimen and side effects, as well as answered a weekly mood questionnaire | Unannounced pill count via telephone call. | RCT of 28 participants to receive Heart2HAART (+ DOT + adherence counseling; n=19) or DOT + adherence counseling alone (n=9) | 63% reported no difficulty using the intervention; 94% reported reminders did not interfere with daily activities; no group differences in ART adherence at 3-month follow-up. |

| Gustafson et al. (2016) [33]; A-CHESS |

Patients at 3 clinics (1 in Massachusetts and 1 in Wisconsin, USA) who meet the criteria for opioid use disorder of at least moderate severity and taking methadone, injectable naltrexone, or buprenorphine | Mobile application; Based on Self-Determination Theory; Functionality includes a list of preapproved supporters to call, CBT skills, self-monitoring, location tracker alerting participant to high-risk locations, just in time coping supports, counselor dashboard, and HIV/HCV screening | % days using illicit opioids over 24 months | RCT of 440 methadone maintenance therapy patients to medication-assisted treatment (MAT) or MAT + A-CHESS | In Progress |

| Glasner-Edwards et al. (2016) [34]; TXT-CBT |

HIV-positive adults with co-morbid substance use disorders residing in Los Angeles, CA, USA | Text messaging; 12-week CBT intervention targeting ART adherence, risk behaviors, and drug use; messages include medication reminders, CBT skills for drug relapse prevention, HIV risk behavior messages, ART adherence promotion messages, messages to manage cravings in real time, and on-call clinician telephone call when requested through SMS | Unannounced pill count and chart review documentation of VL; urine screen and Timeline Followback for substance use; HIV risk behavior | RCT of 50 participants to receive TXT-CBT or SOC for HIV medical management. | In Progress |

| Festinger et al. (2016) [35]; CJ-CARE |

Adults (of all sero-status) residing in Philadelphia, PA, USA charged with a non-violent felony offence and in need of treatment for drug abuse or dependence. | Three 20-minute computer-based sessions that included a brief risk assessment, review of identified risks, skills building videos, and the development of a risk prevention action plan. | Self-reported HIV testing at 6-, 12- and 18-week post-intervention; number of condoms taken (out of 30) after each intervention session; High risk drug and sexual behavior. | RCT of 200 participants randomized to receive a modified version of the Computer Assessment and Risk Reduction Education (CARE), CJ-CARE, or an attention control. | 89% completed all three intervention sessions; significantly higher HIV testing among the CJ-CARE group; mixed findings for condom procurement by group; significant time effect for sex risk scores, but no group effect. |

| Jongbloed et al. (2016) [36]; Cedar Project WelTel mHealth intervention |

HIV-negative young Indigenous people who use illicit drugs in two Canadian cities and are enrolled in the Cedar Project cohort study. | Weekly text messaging to participants, with telephone follow-up from case managers for participants who have a specific problem or need | HIV infection (assessed by a HIV propensity score) at 6 months | RCT of 200 participants randomized to the Cedar Project WelTel mHealth intervention or control (the Cedar Project cohort) | In Progress |

| Cordova et al. [37] Storytelling 4 Empowerment (S4E) |

Adolescents (13–22 years old; 53% binge drinking ≤90 days;47% lifetime drug use) recruited in a clinic waiting room in Southeast Michigan in the US. | Mobile application; Technology-based adaptation of the face-to-face Storytelling for Empowerment (SFE) intervention to be delivered in primary care settings prior to a provider visit; S4E consisted of 2 modules: 1) HIV/STI module; 2) Risk Assessment, Alcohol and Drugs module | Reduce condomless sex, increases HIV testing, and increase skills to resist drug use | Single arm study of 30 adolescent youth who received the S4E intervention and participated in a focus group or an individual interview | Only intervention acceptability reported. Adolescents found the content and format (e.g., videos) of the modules engaging, and stated that receiving the intervention while they wait for their appointment was ideal; however, they noted that the intervention must be brief and protect their confidentiality. |

Among the five mobile app interventions [19, 20, 23, 33, 37], features include: self-management skills development; drug use self-monitoring; alerts to high-risk locations; skills development for resisting drug use; ways to contact support network members, counselors, and peer navigators; and ART adherence and appointment reminders for participants with HIV. Of the two completed studies, one reported higher mean weeks of opioid abstinence for men receiving the mobile app plus standard methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) compared to a historical control of patients on standard MMT [20]. However, the other mobile app intervention tailored for HIV-positive substance-users did not demonstrate improvement in ART adherence levels [23]. Two recent pilot studies reported only on intervention acceptability, with study outcome results forthcoming [19, 37]. In both studies, participants reported that the intervention was easy to use and overall engaging.

Two SMS interventions, one of which is the only intervention study conducted outside of the US (i.e., in Canada) [36], are in progress [34, 36]. Jongbloed and colleagues [36] will use the approach similar to that taken in the WelTel study [38], in that HIV-negative, young Indigenous participants will be sent a weekly text message asking them how they are doing. Follow-up telephone calls are made to participants reporting any difficulties or who request assistance. In contrast, Glasner-Edwards et al. [34] will send text messages to HIV-positive adults with a co-morbid substance use disorder to address ART adherence, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) based skills for drug relapse prevention, and ways to manage cravings, as well as providing access to an on-call clinician.

Finally, one recent computer-based interventions is available, in which Festinger and colleagues [35] randomized 200 adults charged with a non-violent felony offence and in need of drug treatment to receive either an attention control or a 3-session (20 minutes per session) intervention that included a risk assessment, review of identified risks, skill building videos, and a risk prevention action plan tool. Nearly all participants in the experimental group (89%) completed all three modules, and significant differences were found in HIV testing, but not condom procurement or sex risk.

Conclusion

Illicit drug use is highly prevalent among groups at risk and living with HIV, prompting continued efforts to find novel ways to assess drug use and intervene with drug-using populations. Technology-based EMA methods for real-time assessment of drug use yield results that are highly correlated with those from more conventional assessment approaches, and generally result in higher reported illicit drug use. Additionally, rich data about the intrapersonal, social and environmental contexts of drug use may be captured with technology-based EMA methods, while avoiding recall and other (social desirability) biases. The use of text and mobile apps to record frequently-occurring behaviors and their situational correlates may be extended to trigger messages or activities to intervene on those behaviors in real time. These approaches, called “ecological momentary interventions” (or EMIs) [39], have been used to address anxiety [40, 41] and sex risk [42], alcohol [43, 44], smoking [45], and diet and weight loss [46, 47] behaviors. EMI approaches may be likewise used to assess drug use behaviors in real time to provide brief, targeted messages during risky drug events reported by participants. Overall, text messaging and mobile app EMA approaches are portable, flexible, and relatively non-intrusive assessment methods and should be considered in future studies to better understand and intervene on drug use behaviors among groups at risk for HIV and other STIs.

This review revealed high interest among US-based drug using groups in technology-based intervention approaches. However, five of the eight intervention studies reviewed here are still in progress or only report intervention acceptability, with results expected soon; two of the studies reporting intervention outcomes are small-scale pilot studies. Results from only one recent large efficacy trial of a technology-based HIV risk reduction intervention for drug users [35] showed that those receiving a computerized intervention demonstrated higher HIV testing rates than those in the attention control; however, no differences in sex risk was found. Earlier studies showed that tailored text messages reduced HIV risk behavior among methamphetamine users [48, 49]. Nonetheless, there continues to be a clear need for larger trials to establish the efficacy of different technology-based approaches (e.g., text, mobile app) for a variety of drug-using populations (i.e., heroin users vs. stimulant users).

Future research in these areas should include continual assessment of technology adoption and intervention preferences among drug-using populations to ensure that interventions are appropriately matched to users’ needs. Such assessments may help to identify groups of drug-using persons who need pre-training to bolster their technology literacy in preparation for intervention delivery. In addition, current and in-progress technology-based interventions use a variety of components to address high-risk drug using behaviors. It remains unknown which components most effectively reduce risks related to drug use, or whether certain components should be used for specific sub-groups of drug users (e.g., opioid users may require higher virtual counselor support compared to stimulant users). The outcomes of most studies reviewed here have not been reported; doing so may help shed light on important questions related to optimal intervention modality and target population. Finally, all but one (conducted in Canada) of the recent technology-based interventions reviewed were conducted in the US. Although there are numerous recent online surveys of HIV risk behaviors in countries outside the US [50–52], expanding technology-based HIV intervention research among drug users in global settings should be a priority.

Key points.

Text messaging and mobile app EMA approaches are portable, flexible, and relatively non-intrusive assessment methods and should be considered in future studies that wish to understand the contexts of drug use among groups at risk for HIV and other STIs.

Despite concerns about the low rates of technology adoption and use among some groups of illicit drug users, there is high interest among US-based illicit drug users in technology-based intervention approaches.

Studies are needed to continually assess technology adoption and intervention preferences among drug-using populations to ensure that interventions are appropriately matched to users’ needs.

There continues to be a clear need for larger trials to establish the efficacy of different technology-based approaches for drug-using populations.

Studies that assess the impact of specific intervention components on drug use and other high-risk behaviors are recommended.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support and Sponsorship

This work was supported by a NIH awards that support Dr. Horvath (1U19HD089881 [PIs: Hightow-Weidman & Sullivan]; 5R01DA039950 [PI: Horvath]) and Drs. LeGrand, Muessig and Bauermeister (1U19HD089881 [PIs: Hightow-Weidman & Sullivan]). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the funding agencies.

We thank the Duke University’s Library Service for their assistance during the literature review.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

None

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, (1/1/2016 to 3/31/2017) have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Mathers BM, et al. Global epidemiology of injecting drug use and HIV among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. The Lancet. 372(9651):1733–1745. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Bassel N, et al. Drug use as a driver of HIV Risks: Re-emerging and emerging issues. Current opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2014;9(2):150–155. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lansky A, et al. Estimating the Number of Persons Who Inject Drugs in the United States by Meta-Analysis to Calculate National Rates of HIV and Hepatitis C Virus Infections. PLOS ONE. 2014;9(5):e97596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plankey MW, et al. The relationship between methamphetamine and popper use and risk of HIV seroconversion in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes: JAIDS. 2007;45(1):85–92. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3180417c99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thiede H, et al. Determinants of recent HIV infection among Seattle-area men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(Suppl 1):S157–64. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.098582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zlotorzynska M, Sullivan P, Sanchez T. The Annual American Men’s Internet Survey of Behaviors of Men Who Have Sex With Men in the United States: 2015 Key Indicators Report. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2017;3(1):e13. doi: 10.2196/publichealth.7119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Downing MJ, Jr, Chiasson MA, Hirshfield S. Recent anxiety symptoms and drug use associated with sexually transmitted infection diagnosis among an online US sample of men who have sex with men. J Health Psychol. 2016;21(12):2799–2812. doi: 10.1177/1359105315587135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt AJ, et al. Illicit drug use among gay and bisexual men in 44 cities: Findings from the European MSM Internet Survey (EMIS) Int J Drug Policy. 2016;38:4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melendez-Torres GJ, et al. Findings from within-subjects comparisons of drug use and sexual risk behaviour in men who have sex with men in England. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;28(3):250–258. doi: 10.1177/0956462416642125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammoud MA, et al. Following Lives Undergoing Change (Flux) study: Implementation and baseline prevalence of drug use in an online cohort study of gay and bisexual men in Australia. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;41:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shiffman S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in studies of substance use. Psychol Assess. 2009;21(4):486–97. doi: 10.1037/a0017074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linas BS, et al. Utilizing mHealth methods to identify patterns of high risk illicit drug use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;151:250–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linas BS, et al. Capturing illicit drug use where and when it happens: an ecological momentary assessment of the social, physical and activity environment of using versus craving illicit drugs. Addiction. 2015;110(2):315–25. doi: 10.1111/add.12768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirk GD, et al. The exposure assessment in current time study: implementation, feasibility, and acceptability of real-time data collection in a community cohort of illicit drug users. AIDS Res Treat. 2013;2013:594671. doi: 10.1155/2013/594671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Genz A, et al. Uptake and Acceptability of Information and Communication Technology in a Community-Based Cohort of People Who Inject Drugs: Implications for Mobile Health Interventions. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3(2):e70. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.3437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horvath KJ, et al. Engagement in HIV Medical Care and Technology Use among Stimulant-Using and Nonstimulant-Using Men who have Sex with Men. AIDS Research and Treatment. 2013;2013:11. doi: 10.1155/2013/121352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collins KM, et al. Factors associated with patterns of mobile technology use among persons who inject drugs. Subst Abus. 2016;37(4):606–612. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2016.1176980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Westergaard RP, et al. Acceptability of a mobile health intervention to enhance HIV care coordination for patients with substance use disorders. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2017;12(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s13722-017-0076-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20•.Guarino H, et al. A mixed-methods evaluation of the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a mobile intervention for methadone maintenance clients. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016;30(1):1–11. doi: 10.1037/adb0000128. Mobile app pilot intervention showing high feasibility among methadone maintenance clients, as well as higher mean weeks opioid abstinent by urine toxicology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21••.Linas BS, et al. Ecological Momentary Assessment of Illicit Drug Use Compared to Biological and Self-Reported Methods. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016;4(1):e27. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.4470. In addition to comparing EMA to standard self-reporting methods (A-CASI), real-time collection of cocaine and/or heroin use through EMA is compared to biological measures of drug use. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22•.Przybyla SM, et al. Feasibility and Acceptability of a Smartphone App for Daily Reports of Substance Use and Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence among HIV-Infected Adults. AIDS Res Treat. 2016;2016:9510172. doi: 10.1155/2016/9510172. This study found high retention and compliance among HIV-positive participants using an app-based EMA to collect substance use and adherence to ART over a 2-week period. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23•.Himelhoch S, et al. Pilot feasibility study of Heart2HAART: a smartphone application to assist with adherence among substance users living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2017:1–7. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1259454. Mobile app pilot intervention to assist with ART adherence among HIV-positive substance users, although no effects on ART adherence found. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Y, et al. Alcohol misuse, risky sexual behaviors, and HIV or syphilis infections among Chinese men who have sex with men. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;168:239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang C, et al. Factors Associated with Alcohol Use Before or During Sex Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in a Large Internet Sample from Asia. LGBT Health. 2016;3(2):168–74. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fama R, et al. Impairments in Component Processes of Executive Function and Episodic Memory in Alcoholism, HIV Infection, and HIV Infection with Alcoholism Comorbidity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40(12):2656–2666. doi: 10.1111/acer.13250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis A, et al. Associations Between Alcohol Use and Intimate Partner Violence Among Men Who Have Sex with Men. LGBT Health. 2016;3(6):400–406. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delker E, Aharonovich E, Hasin D. Interviewer-administered TLFB vs. self-administered computerized (A-CASI) drug use frequency questions: a comparison in HIV-infected drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;161:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rowe C, et al. Concordance of Text Message Ecological Momentary Assessment and Retrospective Survey Data Among Substance-Using Men Who Have Sex With Men: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016;4(2):e44. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.5368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30•.Smiley SL, et al. Feasibility of Ecological Momentary Assessment of Daily Sexting and Substance Use Among Young Adult African American Gay and Bisexual Men: A Pilot Study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2017;6(2):e9. doi: 10.2196/resprot.6520. This study demonstrates high retention of participants using EMA text-messages to collect frequency of alcohol use, marijuana use, and sexting over 2 weeks. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shrestha R, et al. Examining the Acceptability of mHealth Technology in HIV Prevention Among High-Risk Drug Users in Treatment. AIDS Behav. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1637-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horvath KJ, et al. Creating Effective Mobile Phone Apps to Optimize Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence: Perspectives From Stimulant-Using HIV-Positive Men Who Have Sex With Men. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016;4(2):e48. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.5287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gustafson DH, Sr, et al. The effect of bundling medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction with mHealth: study protocol for a randomized clinical trial. Trials. 2016;17(1):592. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1726-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glasner-Edwards S, et al. A Cognitive Behavioral Therapy-Based Text Messaging Intervention Versus Medical Management for HIV-Infected Substance Users: Study Protocol for a Pilot Randomized Trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016;5(2):e131. doi: 10.2196/resprot.5407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35••.Festinger DS, et al. Examining the efficacy of a computer facilitated HIV prevention tool in drug court. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;162:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.02.026. Only recent large-scale efficacy trial of a computerized intervention conducted in the criminal justice system; results demonstrated higher HIV testing rates, but not lower sex risk. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jongbloed K, et al. The Cedar Project WelTel mHealth intervention for HIV prevention in young Indigenous people who use illicit drugs: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17(1):128. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1250-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cordova D, et al. The Usability and Acceptability of an Adolescent mHealth HIV/STI and Drug Abuse Preventive Intervention in Primary Care. Behav Med. 2016:1–12. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2016.1189396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lester RT, et al. Effects of a mobile phone short message service on antiretroviral treatment adherence in Kenya (WelTel Kenya1): a randomised trial. The Lancet. 2010;376(9755):1838–1845. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61997-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beckjord E, Shiffman S. Background for Real-Time Monitoring and Intervention Related to Alcohol Use. Alcohol Res. 2014;36(1):9–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pramana G, et al. The SmartCAT: an m-health platform for ecological momentary intervention in child anxiety treatment. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20(5):419–27. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Newman MG, et al. A randomized controlled trial of ecological momentary intervention plus brief group therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Psychotherapy (Chic) 2014;51(2):198–206. doi: 10.1037/a0032519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shrier LA, Spalding A. “Just Take a Moment and Breathe and Think”: Young Women with Depression Talk about the Development of an Ecological Momentary Intervention to Reduce Their Sexual Risk. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2017;30(1):116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Riordan BC, et al. A Brief Orientation Week Ecological Momentary Intervention to Reduce University Student Alcohol Consumption. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2015;76(4):525–9. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wright CJ, et al. An Ecological Momentary Intervention to Reduce Alcohol Consumption in Young Adults Delivered During Drinking Events: Protocol for a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2017;6(5):e95. doi: 10.2196/resprot.6760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Businelle MS, et al. An Ecological Momentary Intervention for Smoking Cessation: Evaluation of Feasibility and Effectiveness. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(12):e321. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boh B, et al. An Ecological Momentary Intervention for weight loss and healthy eating via smartphone and Internet: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17:154. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1280-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brookie KL, et al. The development and effectiveness of an ecological momentary intervention to increase daily fruit and vegetable consumption in low-consuming young adults. Appetite. 2017;108:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reback CJ, et al. Exposure to Theory-Driven Text Messages is Associated with HIV Risk Reduction Among Methamphetamine-Using Men Who have Sex with Men. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(Suppl 2):130–41. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0985-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reback CJ, et al. Text messaging reduces HIV risk behaviors among methamphetamine-using men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(7):1993–2002. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0200-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Young SD, et al. Substance use and sexual risk behaviors among Peruvian MSM social media users. AIDS Care. 2016;28(1):112–8. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1069789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao P, et al. Recreational Drug Use among Chinese MSM and Transgender Individuals: Results from a National Online Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0170024. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Togari T, et al. Recreational drug use and related social factors among HIV-positive men in Japan. AIDS Care. 2016;28(7):932–40. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1140888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Santos GM, et al. Feasibility, acceptability and tolerability of targeted naltrexone for non-dependent methamphetamine-using and binge-drinking men who have sex with men. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2016;72(1):21–30. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]