Abstract

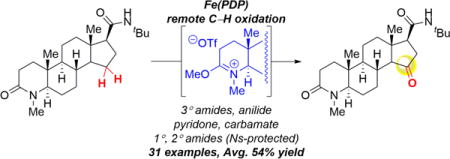

Amide-containing molecules are ubiquitous in natural products, pharmaceuticals, and materials science. Due to their intermediate electron-richness, they are not amenable to any of the previously developed N-protection strategies known to enable remote aliphatic C—H oxidations. Using information gleaned from a systematic study of the main features that makes remote oxidations of amides in peptide settings possible, we developed an imidate salt protecting strategy that employs methyl trifluoromethanesulfonate (MeOTf) as a reversible alkylating agent. The imidate salt strategy enables, for the first time, remote, non-directed, site-selective C(sp3)—H oxidation with Fe(PDP) and Fe(CF3PDP) catalysis in the presence of a broad scope of tertiary amides, anilide, 2-pyridone, and carbamate functionality. Secondary and primary amides can be masked as N-Ns amides to undergo remote oxidation. This novel imidate strategy facilitates late-stage oxidations in a broader scope of medicinally important molecules and may find use in other C—H oxidations and metal-mediated reactions that do not tolerate amide functionality.

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Nitrogen-containing functionalities append notable physical and bioactivity properties to organic molecules. Among them, amides are considered a privileged scaffold in medicinal chemistry, natural products, and materials science.1 Therefore, the development of a method to selectively oxidize inert remote C(sp3)—H bonds on amide-containing molecules would be a powerful tool for late-stage functionalization of important organic structures.2

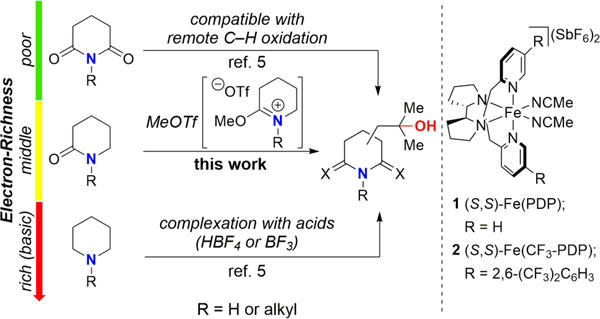

Site-selective and -divergent oxidation of tertiary (3°) and secondary (2°) C—H bonds has been demonstrated with small molecule catalysts, Fe(PDP) 1 and Fe(CF3PDP) 2, respectively.3 Such catalysts are thought to proceed via a biomimetic, stepwise mechanism. A highly electrophilic Fe oxidant [likely an Fe(oxo)carboxylate] affects C—H cleavage via a late, product-like transition state where its capacity to differentiate among C—H bonds based on their electronics, sterics, and stereoelectronics properties controls site-selectivities.4 Recently, these catalysts were shown to oxidize remote C—H bonds in the presence of basic amines and electron-poor imides.5 Electron-rich amines, previously used as directing groups,6 promoted remote C—H oxidations after protonation by a strong Brønsted acid (HBF4) or complexation with an oxidatively stable Lewis acid (BF3).5 The electronically deactivated ammonium salts and BF3 adducts provided strong inductive deactivation of hyperconjugatively activated sites α to nitrogen and promoted remote oxidations of the most electron rich aliphatic C—H bonds. Imides, bearing two electron-withdrawing carbonyl groups on the nitrogen atom, are well-tolerated and also promote remote C—H oxidation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

C—H Oxidation of Nitrogen-Containing Molecules.

Despite the ability to use amides as directing groups for C—H functionalizations proceeding via organometallic intermediates,7,8 there is no general means for effecting non-directed, remote aliphatic C—H hydroxylation of simple amide-containing molecules.9 The intermediate electron-richness of simple amide-containing molecules makes them not electron rich enough to bind irreversibly with acids (i.e. HBF4 and BF3) and not electron deficient enough to enable remote oxidations without protection (Figure 1). Oxidations of amides generally lead to direct oxidation of nitrogen10 or proximal oxidation of hyperconjugatively activated α-C—H bonds.11

Herein, we describe an imidate salt strategy that promotes remote, non-directed, site-selective aliphatic C—H oxidation in amide-containing molecules with electrophilic Fe(PDP) 1 and Fe(CF3PDP) 2 catalysis.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

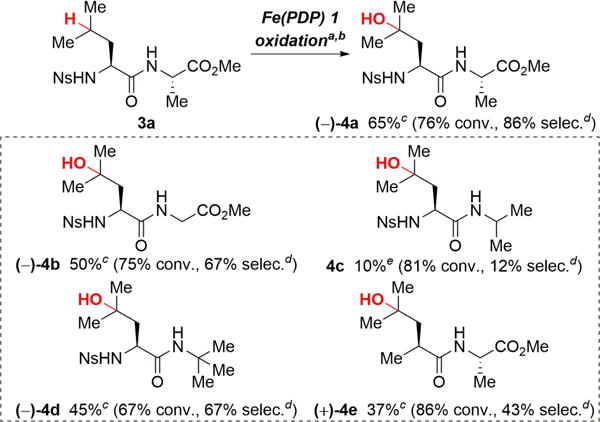

A significant deviation from the reactivity trend in Figure 1 is seen in peptides which can be remotely oxidized at both tertiary and secondary aliphatic C—H bonds with Fe(PDP) 1 and Fe(CF3PDP) 2 catalysis without protection of the amide moiety.12 With the goal of elucidating whether the steric or electronic properties of the substituents flanking the peptide amide bond make it well suited toward remote C(sp3)—H oxidations, we systematically deconstructed dipeptide 3a to determine which of its features is important for maintaining selectivity for remote tertiary C—H bond oxidation over other deleterious oxidation pathways (Scheme 1). Removal of the methyl steric element on C-terminus slightly decreased the yield and selectivity (4b, 50% yield, 67% selectivity). Replacement of the methyl ester (CO2Me) by a methyl group, however, significantly decreased the yield and selectivity for remote oxidation product (4c, 10% yield, 12% selectivity), likely due to α-oxidation of the adjacent tertiary C—H bond promoted by the amide nitrogen. When the α-C—H bond is replaced with a methyl group, removing the alternate proximal site of oxidation, the yield and selectivity for remote oxidation are restored (4d, 45% yield, 67% selectivity). Evaluation of groups flanking the carbonyl of the amide moiety showed a strong dependence on electronics: replacing the electron-withdrawing N-Ns substituent with a more sterically demanding methyl group13 furnished the remote oxidation product 4e in moderate 37% yield and low selectivity (43%).

Scheme 1. C—H Oxidation of Peptides.

aIsolated yield is average of three runs, % conversion and % selectivity in parentheses. bslow addition: 25 mol% 1, AcOH (5.0 equiv.), H2O2 (9.0 equiv.), MeCN, syringe pump (60 min), cStarting material recycled 1×. dSelectivity = yield/conversion. eNMR yield using PhNO2 as an internal standard.

Collectively, these results suggest that electron-withdrawing substitution flanking both sides of the amide bonds in peptides are most effective for enabling remote oxidations. We therefore sought to find a way to reversibly electronically deactivate the amide bond in simple amides where such adjacent electron withdrawing groups are not native.

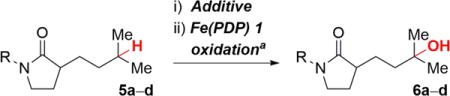

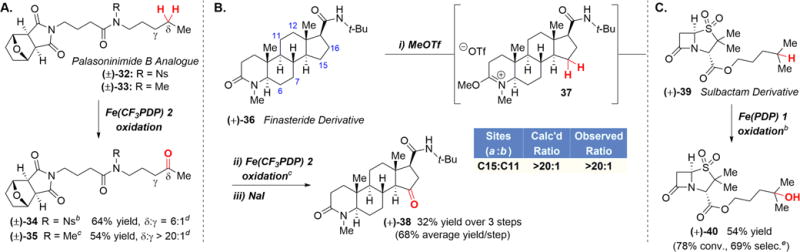

In the absence of protection on nitrogen, 3° and 2° lactams (5a, 5b) containing a remote tertiary site of oxidation yielded no desired product due to the competitive oxidation of α-C—H bonds (Table 1, entries 1 and 6). Previous complexation strategies using Brønsted or Lewis acids, such as HBF4, H2SO4, and BF3, provided no improvement of the reaction due to the reversible nature of the complexation (entries 2−4).5,14 We envisioned that non-basic, but nucleophilic amides would react with an alkylating reagent to form a stable imidate salt. Previously, imidate salts had only been employed as intermediates to activate unreactive amides toward nucleophilic substitutions.15 We hypothesized that under these weakly acidic, mild oxidation conditions with short reaction times, these imidate salts would be stable. Moreover, the cationic functionality would provide strong electronic deactivation to neighboring sites to promote remote C—H oxidation with the electrophilic oxidant generated with Fe(PDP) and H2O2.4 Based on this concept, using MeOTf as additive we observed the desired oxidation product 6a in excellent yield after a mild decomplexation with sodium iodide (NaI) at room temperature (Table 1, entry 5 and Scheme 2, equation 1, 59% isolated yield over 3 steps),16 providing the first example of remote oxidation in the presence of a simple tertiary amide.

Table 1.

Reaction Optimization

| A. Remote 3° C–H Oxidation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Entry | Lactam | R | Additive | Yield [%] (rsm)b |

| 1 | 5a | Me | - | 0 (0) |

| 2 | 5a | Me | HBF4c | 0 (0) |

| 3 | 5a | Me | H2SO4c | 0 (0) |

| 4 | 5a | Me | BF3•OEt2c | 0 (0) |

| 5 | 5a | Me | MeOTfd | 59 (10) |

| 6e | 5b | H | - | 0 (0) |

| 7e | 5c | Boc | - | 24f (14) |

| 8e | 5d | Ns | - | 62 (7) |

| B. Remote 2° C–H Oxidation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Entry | Lactam | R | Additive | Yield [%] (rsm)b | Selectivityg |

| 9 | 5e | Me | MeOTfd | 56 (12) | > 20:1 δ/γ |

| 10e,h | 5f | Ns | - | 54 (14) | 4.1:1 δ/γ |

|

| |||||

|

| |||||

Slow addition: 15 mol% 1 or 25 mol% 2, AcOH (5.0 equiv.), H2O2 (9.0 equiv.), MeCN, syringe pump (60 min).

lsolated yield is average of three runs, % rsm is given in parentheses.

(i) additive (1.1 equiv.), CH2CI2, concentrated under reduced pressure, (ii) slow addition. (iii) 1M NaOH.

(i) MeOTf (1.2 equiv.), CH2CI2, concentrated under reduced pressure, (ii) slow addition. (iii) MnO2 (0.5 equiv.), 0°C.* (iv) Nal (2 equiv.), MeCN, rt.

lterative addition (3×): 5 mol% 1 or 2, AcOH (0.5 equiv.), H2O2 (1.2 equiv.), MeCN.

NMR yield using PhNO2 as an internal standard.

Based on isolation.

Starting material recycled 1×. *Pretreatment with MnO2 prior to the Nal-mediated decomplexation is necessary to quench excess of H2O2 and ensure reproducibility.

Scheme 2.

Decomplexation of Imidate Salts.

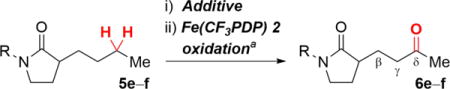

In the case of 2° amides, more conventional electron-withdrawing protecting groups on nitrogen may prevent deleterious α- and N-oxidation and promote remote oxidations. Whereas the reaction of Boc-protected lactam (5c) was not effective (entry 7), 4-nitrobenzenesulfonyl (Ns) protection provided remote oxidized product 6d in 62% yield (entry 8). Interestingly, N-Ns protection in secondary amines furnishes α-oxidation products whereas for secondary amides remote oxidation is observed.12 The remote oxidation strategies for 3° and 2° amides shown above could be also used for methylene C—H oxidation with Fe(CF3PDP) 2 (entries 9, 10). Significantly, the imidate salt strategy gave better site-selectivities for remote δ oxidation than Ns protection, suggesting that the cationic nature of the imidate salt provides stronger electronic deactivation than Ns protection.17 This feature of the imidate protection strategy promotes highly site-selective remote oxidations with electrophilic Fe(PDP) 1 and Fe(CF3PDP) 2 oxidants, previously elucidated to have a strong preference for oxidizing the most electron rich site in substrates.3,5 In both the 3° and 2° oxidized products 6d and 6f, the N-Ns protected amide could be readily deprotected via K2CO3/PhSH in 90% and 88% yield, respectively (See Supporting Information). N-Nosyl protection is also useful for 1° amides: N-Ns-protected hexanamide 5g was oxidized at a remote site to form the desired product 6g in good yield and 5:1 site-selectivity.

Typically, the imidate salt can be deprotected via an SN2 reaction mediated by NaI (Scheme 2, Equation 1). However, these intermediates may also be intercepted with other nucleophiles. The Fe(CF3PDP) 2-catalyzed oxidation of lactam 5e followed by treatment of the crude imidate salt with lithium prop-2-en-1-olate underwent a Meerwein−Eschenmoser [3,3]-rearrangement to provide the allylated compound 7 in 26% overall yield for 3 steps (64% yield per step) (Scheme 2, Equation 2).18

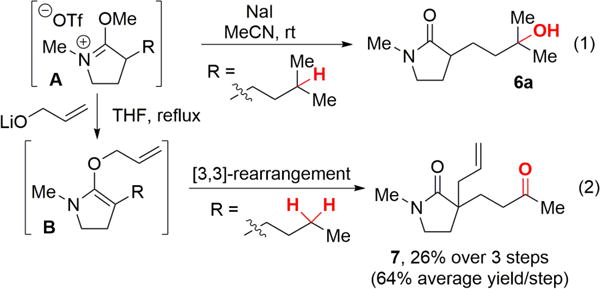

Substituted lactams are prevalent substructures in natural products and medicinal agents.1 Five- and six-membered ring lactams with N-alkyl chains uniformly provided remote 3° and 2° C—H bond oxidation products in high yields and selectivities (Table 2, 8−11). The inductive effect of the imidate salt enabled high site-selectivities for Fe(CF3PDP) 2-catalyzed oxidation at alkyl substitution α to the amide carbonyl: cyclopentyl substituted 5- and 6-membered lactams were oxidized with Fe(CF3PDP) 2 at the methylene sites most remote from this electron-withdrawing moiety to furnish ketones 12 and 13. Medium-sized lactams (7- and 8-membered) showed analogous reactivity and selectivity trends (14−18). Significantly, no ring oxidations were observed even with the eight-membered lactams (15 and 17).

Table 2.

|

Isolateci overall yield is an average of three runs, % rsm is given in parentheses.

(i) MeOTf (1.2 equiv.), CH2CI2, 12-24h, concentrated under reduced pressure, (ii) s6low addition: 15 mol% 1 or 25 mol% 2, AcOH (5.0 equiv.), H2O2 (9.0 equiv.), MeCN, syringe pump (60 min). (iii) MnO2 (0.5 equiv.), 0 °C.* (iv) Nal (2 equiv.), MeCN, rt, 1h.

Decomplexation was performed with Nal (3 equiv.) at rt for 2h.

Decomplexation was performed at 80 °C for 1h.

Based on isolation.

Iterative addition (3×): 5 mol% 1 or 2, AcOH (0.5 equiv.), H2O2 (1.2 equiv.), MeCN, 30 min. *Pretreatment with MnO2 prior to the Nal-mediated decomplexation is necessary to quench excess of H2O2 and ensure reproducibility.

The imidate salt strategy can be applied to acyclic amides to equal effect. In a series of dialkyl amides of varying steric bulk (Me, Et, and i-Pr), remote tertiary C—H hydroxylation with Fe(PDP) 1 provided the oxidized products (19−21) in excellent overall yields (avg. 54% for three steps), suggesting that formation and stability of the imidate salt is not significantly impacted by sterics at the nitrogen. Interestingly, pyrrolidine amides, general structures in medicinal compounds, also provided remote 3° and 2° C—H oxidation products (22−24) in excellent yields.

We proceeded to challenge the efficiency of these amide-protection strategies in the context of more complex medicinally-relevant core structures. The fused tricyclic lactam, containing a quinolizidin-2-one moiety that is a prevalent unit in alkaloids, such as matrine, was evaluated for oxidation using the imidate salt strategy.19 The imidate underwent Fe(CF3PDP) 2 oxidation to furnish ketone 25 on the most remote methylene site in good yield and excellent site-selectivity (only one oxidized product observed). The quinolizidinone core, that may have been susceptible to oxidation, remained unaffected.

Notably, β-lactams, the most prevalent lactam core in pharmaceuticals such as antibiotics,1,20 were amenable to this protection strategy, despite the potential ring strain introduced during imidate formation. 3-Carene- and α-pinene-derived β-lactams underwent Fe(CF3PDP) 2-catalyzed remote methylene oxidations at their N-alkyl side chains to afford 26 and 27 in good yields and selectivities. Significantly, their sensitive terpene cores were shielded from C—H cleavage via the strong inductive deactivation afforded by the imidate salt formed at the fused b-lactam ring.

We questioned the generality of this strategy for other nitrogen functionality of intermediate electron-richness. The challenging anilide motif, which is easily oxidized by strong oxidants due to the electron-richness of the aromatic ring, was effectively protected as an imidate salt to provide remote tertiary hydroxylated product 28 with Fe(PDP) 1 in 46% overall yield. 2-Pyridone, which exists in a variety of bioactive compounds and incorporates a very sensitive moiety known to be oxidized by monooxygenases,21 was effectively protected from oxidation with this strategy and underwent Fe(CF3PDP) 2-oxidation to afford remote methylene oxidation ketone 29 in 51% overall yield and 5.3:1 site-selectivity. The diminished site-selectivity for compound 29 - relative to analogous products derived from amide imidates- is attributed to the dampened positive charge of the imidate due to delocalization around the conjugated ring. Carbamates, which promote α-heteroatom oxidation under standard conditions, furnish remote methylene oxidized ketone 30 with Fe(CF3PDP) 2 catalysis in 53% overall yield using this imidate salt strategy. It has been previously reported that imides promote remote aliphatic C—H oxidations without protection.5 Using the nosyl-protection strategy, a more electron rich uracil analogue was successfully oxidized remotely with Fe(PDP) 1 to afford alcohol 31 in 64% yield.

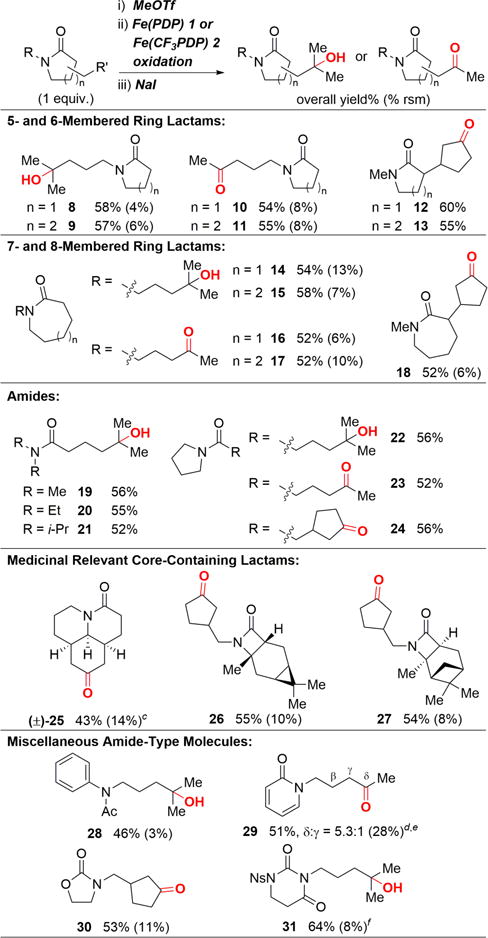

Finally, the robustness of this strategy was evaluated in the late-stage oxidation of a series of amide-containing natural product derivatives. Palasoninimide B, bearing an interesting cantharimide core, is a natural product recently isolated from Mylabis phalerata Palla and found to be a potent inhibitor of hepatitis B virus (HBV).22 The Fe(CF3PDP) 2 oxidation of the nosylated palasoninimide B analogue 32 resulted in remote oxidation product 34 in 64% yield and 6:1 selectivity with the cyclic ether cantharimide substructure untouched (Scheme 3A). For N-methyl derivative 33, the higher nucleophilicity of the amide nitrogen versus that of the imide led it to preferentially reacting with the alkylating reagent to form a stable imidate salt. The Fe(CF3PDP) 2 oxidation resulted in only the remote oxidized product 35 in 54% overall yield (>20:1; 1H NMR, 82%/step). The higher site-selectivity in Fe(CF3PDP) 2 methylene oxidation with the imidate salt versus N-Ns protection strategies is consistent with previous trends observed on simpler substrates (Table 1B).

Scheme 3. Late-Stage Diversification of Amide-Containing Molecules.a.

aIsolated yield is average of three runs. bIterative addition (3×): 5 mol% 1 or 2, AcOH (0.5 equiv.), H2O2 (1.2 equiv.), MeCN, 30 min. c(i) MeOTf (1.2 equiv.), CH2CI2 12h, concentrated under reduced pressure. (ii) Slow addition: 25 mol% 2, AcOH (5.0 equiv.), H2O2 (9.0 equiv.), MeCN, syringe pump (60 min). (iii) MnO2 (0.5 equiv.), 0°C.* (iv) Nal (2 equiv.), MeCN, rt, 1h. dBased on Isolation. eSelectivity = yield/conversion. *Pretreatment with MnO2 prior to the Nal-mediated decomplexation is necessary to quench excess of H2O2 and ensure reproducibility.

Finasteride, known as a type II and type III 5α-reductase inhibitor, is a medication used for the treatment of enlarged prostate and pattern hair loss.23 The azasteroid structure contains two amides: one in the A-ring of the steroidal core and the other a t-Bu amide on the D-ring (Scheme 3B). We envisioned that only the sterically exposed A-ring lactam of finasteride derivative 36 would react with MeOTf to form the imidate salt 37. Based on our studies with the t-Bu amide of peptide 3d, we envisioned that this unprotected amide moiety would not inhibit productive catalysis (Scheme 1). Using the previously developed quantitative reactivity model,3c we predicted that oxidation of 37 using the sterically sensitive Fe(CF3PDP) 2 catalyst would afford primarily D-ring oxidation due to strong electronic deactivation of A- and B-rings by the cationic imidate moiety and steric congestion at the C-ring (See Supporting Information). Treatment of finasteride analogue 36 with MeOTf formed imidate salt 37. Fe(CF3PDP) 2 oxidation and decomplexation with NaI provided C15 ketone 38 in 32% yield over three steps (68% per step) from 36 as a single regioisomer (Scheme 3B). Despite the lack of imidate and amide moieties in the model’s training set,3c this was the predicted major site of oxidation with Fe(CF3PDP) 2. Significantly, this reaction provides the first example of non-directed, aliphatic C–H oxidation at the D-ring of a steroid with a small molecule catalyst.

Sulbactam, a β-lactamase inhibitor used as antibiotic,24 contains an amide moiety electronically reminiscent of a peptide: it is flanked with two strongly electron withdrawing moieties, an ester and a sulfone group (Scheme 3C). We hypothesized that given this, undesired α-nitrogen oxidation would be disfavored in sulbactam ester 39 without any amide protection. Aliphatic C—H oxidation with electrophilic Fe(PDP) catalyst 1 occurred remotely from the innately electron withdrawing sulbactam core at the most electronrich tertiary C—H bond to furnish product 40 in 54% yield and 69% selectivity.

CONCLUSION

We have demonstrated remote Fe(PDP)-catalyzed tertiary and methylene oxidation in a range of amide-containing molecules by employing an imidate salt formation strategy. We envision this strategy will be highly beneficial in the late-stage functionalization of bioactive molecules and assist in the rapid evaluation of their metabolites.25 Moreover, we envision that this novel amide protecting strategy may find uses in other C—H oxidations and metal-mediated reactions where α-oxidation and/or catalyst deactivation is problematic.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

General Procedure for Protection with MeOTf

To a stirring solution of amide-containing molecule (1.0 equiv.) in CH2Cl2 (0.2 M) at 0°C was added MeOTf (1.2 equiv.) dropwise and the reaction mixture was warmed to room temperature and stirred overnight. The reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure and left on high vacuum overnight (12─24 hours) to yield an imidate salt which was either used in the next step without further purification (if imidate salt is a liquid) or recrystallized in Et2O (if imidate salt is a solid).

General Procedure for C—H Oxidation Using the Slow Addition Protocol

The imidate salt (1.0 equiv.) and AcOH (5.0 equiv.) were dissolved in MeCN (0.5 M). A 1 mL syringe was charged with a solution of Fe(PDP) (0.15 equiv.) or Fe(CF3PDP) (0.25 equiv.) in MeCN [0.11 M for Fe(PDP) or 0.19 M for Fe(CF3PDP)]. A 10 mL syringe was charged with a solution of H2O2 (9.0 equiv.) in MeCN (0.75 M). Both syringes were fitted with 25G needles and solutions were added simultaneously into the stirring reaction mixture via a syringe pump over 1 hour. For 0.300 mmol scale the addition rate would be 3.6 mL/h. The reaction solution was stirred for 30 minutes after the addition, for a total reaction time of approximately 1.5 hour.

General Procedure for Imidate Salt Deprotection

After the oxidation, the reaction mixture was cooled to 0°C and MnO2 (0.5 equiv.) was added to quench the excess H2O2. After stirring for 1h, the mixture was filtered through a short celite pad to remove MnO2 and concentrated under reduced pressure. Pretreatment with MnO2 prior to the NaI-mediated decomplexation is necessary to quench excess of H2O2 and ensure reproducibility. The residue was dissolved in MeCN (0.2 M) and NaI (2.0 equiv.) was added. After stirring for 1h at room temperature, the mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure and the residue was partitioned in CHCl3 and saturated aqueous solution of NaHCO3. The organic phase was separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with CHCl3 (twice). The combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude mixture was purified by flash column chromatography to afford the desired oxidation product.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by the NIGMS Maximizing Investigator’s Research Award MIRA (R35 GM122525). We are grateful to The Uehara Memorial Foundation for a fellowship to TN and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico for a fellowship to ECLJr (Proc n° 234643/2014-5). We thank Stephen Ammann and Chloe Wendell for spectra inspection and K. Feng and J. Zhao for checking procedures. We thank Zoetis and Bristol-Myers Squibb for unrestricted grants.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

This Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: xx.xxxx/jacs.xxxxxxx.

Experimental procedures and analytical data (1H, 13C, HRMS) for all new compounds (PDF).

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.(a) Lee FYF, Borzilleri R, Fairchild CR, Kamath A, Smykla R, Kramer R, Vite G. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;63:157. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0724-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Vitaku E, Smith DT, Njardarson JT. J Med Chem. 2014;57:10257. doi: 10.1021/jm501100b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Caruano J, Muccioli GG, Robiette R. Org Biomol Chem. 2016;14:10134. doi: 10.1039/c6ob01349j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Anton A, Baird BR. Kirk−Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. 5th. Vol. 19. Wiley; Weinhein: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) White MC. Science. 2012;335:807. doi: 10.1126/science.1207661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) White MC. Synlett. 2012;23:2746. [Google Scholar]; (c) Cernak T, Dykstra KD, Tyagarajan S, Vachal P, Krska SW. Chem Soc Rev. 2016;45:546. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00628g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Chen MS, White MC. Science. 2007;318:783. doi: 10.1126/science.1148597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen MS, White MC. Science. 2010;327:566. doi: 10.1126/science.1183602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gormisky PE, White MC. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:14052. doi: 10.1021/ja407388y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Bigi MA, Reed SA, White MC. Nat Chem. 2011;3:216. doi: 10.1038/nchem.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bigi MA, Reed SA, White MC. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:9721. doi: 10.1021/ja301685r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Oloo WN, Que L., Jr Acc Chem Res. 2015;48:2612. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howell JM, Feng K, Clark JR, Trzepkowski LJ, White MC. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:14590. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b10299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.For amines as directing groups for C(sp3)—H functionalization, see:; (a) McNally A, Haffemayer B, Collins BSL, Gaunt MJ. Nature. 2014;510:129. doi: 10.1038/nature13389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Topczewski JJ, Cabrera PJ, Saper NI, Sanford MS. Nature. 2016;531:220. doi: 10.1038/nature16957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Xu Y, Young MC, Wang C, Magness DM, Dong G. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:9084. doi: 10.1002/anie.201604268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wu Y, Chen YQ, Liu T, Eastgate MD, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:14554. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b09653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Liu Y, Ge H. Nat Chem. 2017;9:26. [Google Scholar]

- 7.For amides as directing groups for C(sp2)—H functionalization, see:; (a) Zaitsev VG, Daugulis O. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:4156. doi: 10.1021/ja050366h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Patureau FW, Glorius F. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:9982. doi: 10.1021/ja103834b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For a non-directed example, see:; (c) Phipps RJ, Gaunt MJ. Science. 2009;323:1593. doi: 10.1126/science.1169975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.For amides as directing groups for C(sp3)—H functionalization, see:; (a) Reddy BVS, Reddy LR, Corey EJ. Org Lett. 2006;8:3391. doi: 10.1021/ol061389j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wasa M, Engle KM, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:9886. doi: 10.1021/ja903573p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhao R, Lu W. Org Lett. 2017;19:1768. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.For examples of remote C—H bond oxidation in electron-poor or sterically hindered amides conformationally restricted towards hyperconjugative C—H activation, see:; (a) Milan M, Bietti M, Costas M. ACS Cent Sci. 2017;3:196. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.6b00368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kawamata Y, Yan M, Liu Z, Bao DH, Chen J, Starr JT, Baran PS. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:7448. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b03539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rella MR, Williard PG. J Org Chem. 2007;72:525. doi: 10.1021/jo061910n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campos KR. Chem Soc Rev. 2007;36:1069. doi: 10.1039/b607547a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osberger TJ, Rogness DC, Kohrt JT, Stepan AF, White MC. Nature. 2016;537:214. doi: 10.1038/nature18941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Although the A-value for NHNs is unknown, the A-value for NHTs is 0.7, which is significantly smaller than for a methyl group (A-value = 1.7):; Pozharliev IG, Mikhailov St. Izvestiya na Otdelenieto za Khimicheski Nauki. 1970;3:133. [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Lee M, Sanford MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:12796. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b09099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lee M, Sanford MS. Org Lett. 2017;19:572. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b03731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Meerwein H, Florian W, Schön N, Stopp G. Ann. 1961;641:1. [Google Scholar]; (b) Deslongchamps P, Caron M. Can J Chem. 1980;58:2061. [Google Scholar]; (c) Ates A, Curran DP. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:5130. doi: 10.1021/ja010467p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Yamada K, Karuo Y, Tsukada Y, Kunishima M. Chem Eur J. 2016;22:14042. doi: 10.1002/chem.201603120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Kaiser D, Maulide N. J Org Chem. 2016;81:4421. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b00675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.We could not isolate the C—H oxidized imidate salts. However, in cases where we isolated the imidate salt prior to C—H oxidation, the yields were uniformly greater than 90%. Considering that Fe(PDP) and Fe(CF3PDP) oxidations generally proceed in 50–70% yield (see references 3–5), we can assume that the NaI-mediated deprotection goes in excellent yield, making the overall yield very representative of the C―H oxidation.

- 17.Wells PR. Prog Phys Org Chem. 1968;6:111. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coates B, Montgomery DJ, Stevenson PJ. Tetrahedron. 1994;50:4025. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saito K, Takamatsu S, Ohmiya S, Otomasu H, Yasuda M, Kano Y, Murakoshi I. Phytochemistry. 1988;27:3715. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drawz SM, Bonomo RA. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:160. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00037-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Semple G, Andersson BM, Chhajlani V, Georgsson J, Johansson MJ, Rosenquist Å, Swanson L. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:1141. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeng YB, Liu XL, Zhang Y, Li CJ, Zhang DM, Peng YZ, Zhou X, Du HF, Tan CB, Zhang YY, Yang DJ. J Nat Prod. 2016;79:2032. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rasmusson GH, Reynolds GF, Utne T, Jobson RB, Primka RL, Berman C, Brooks JR. J Med Chem. 1984;27:1690. doi: 10.1021/jm00378a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.English AR, Girard D, Jasys VJ, Martingano RJ, Kellogg MS. J Med Chem. 1990;33:344. doi: 10.1021/jm00163a055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stepan AF, Mascitti V, Beaumont K, Kalgutkar AS. Med Chem Commun. 2013;4:631. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.