Abstract

Cyclotides are globular microproteins with a unique head-to-tail cyclized backbone, stabilized by three disulfide bonds forming a cystine knot. This unique circular backbone topology and knotted arrangement of three disulfide bonds makes them exceptionally stable to chemical, thermal and biological degradation compared to other peptides of similar size. In addition, cyclotides have been shown to be highly tolerant to sequence variability aside from the conserved residues forming the cystine knot. Cyclotides can also cross cellular membranes and are able to modulate intracellular protein-protein interactions both in vitro and in vivo. All these features make cyclotides appear as highly promising leads or frameworks for the design of peptide-based diagnostic and therapeutic tools. This article provides an overview on cyclotides and their applications as molecular imaging agents and peptide-based therapeutics.

Keywords: cyclotides, cyclic peptides, cyclic cystine knot, drug design, imaging agents, MCoTI-I, kalata B1

Graphical abstract

Cyclotides are globular microproteins with a unique head-to-tail cyclized backbone, stabilized by three disulfide bonds forming a cystine knot. The present review provides an overview on cyclotides and their applications as molecular imaging agents and peptide-based therapeutics.

INTRODUCTION

Proteins have the most dynamic and diverse role of any macromolecules in the body, which include catalyzing biochemical reactions, forming receptors and channels in membranes, providing intracellular and extracellular scaffolding support, and transporting molecules within a cell or from one organ to another. It is roughly estimated that there are around 20,000 different genes in the human genome.[1] This estimate provides an immense challenge to modern medicine as disease may result when any given protein contains mutations or other abnormalities or is present in an abnormally high or low concentration. Viewed from the perspective of therapeutics, however, this represents a tremendous opportunity in terms of providing protein-protein interactions to target and alleviate human disease.[2] Protein and peptide-based therapeutics have several advantages when targeting protein-protein interactions due to their high specificity and selectivity.[3] However, they also show important limitations such as limited stability to proteolysis and inability to cross biological membranes.[4] In response to this challenge, a number of technologies are starting to emerge to address these issues.[3d, 5]

Special attention has been recently given to the use of highly constrained poly-peptides as extremely stable and versatile scaffolds for the production of high affinity ligands for specific protein capture and/or development of therapeutics.[6] Cyclotides are fascinating micro-proteins (≈30 residues long) present in several families of plants.[7] Naturally-occurring cyclotides display numerous biological properties such as protease inhibitory, anti-microbial, insecticidal, cytotoxic, anti-HIV and hormone-like activities.[8] They share a unique head-to-tail circular knotted topology of three disulfide bridges, with one disulfide penetrating through a macrocycle formed by the two other disulfides and inter-connecting peptide backbones, forming what is called a cystine knot topology (Fig. 1). Cyclotides can be considered as natural combinatorial peptide libraries structurally constrained by the cystine-knot scaffold and head-to-tail cyclization, but in which hypermutation of essentially all residues is permitted with the exception of the strictly conserved cysteines that comprise the knot.[9]

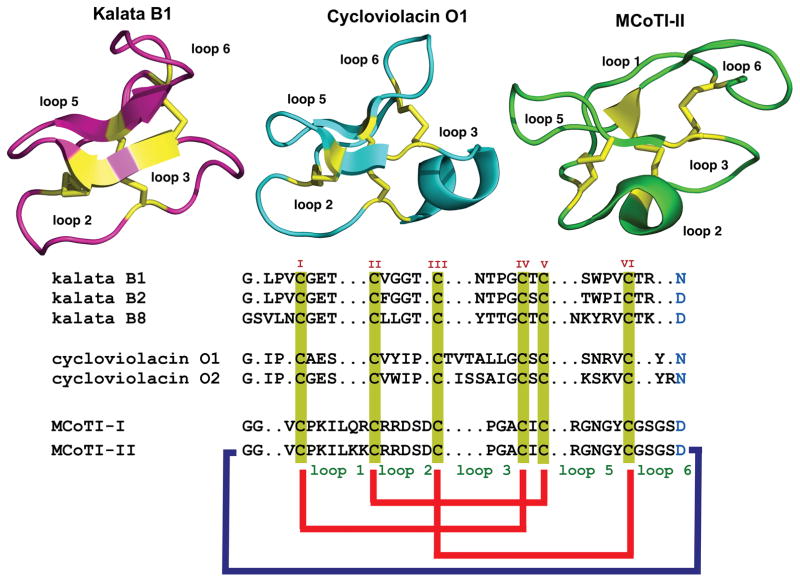

Figure 1.

Primary and tertiary structures of cyclotides belonging to the Möbius (kalata B1, pdb: 1NB1), bracelet (cycloviolacin O1, pdb: 1NBJ) and trypsin inhibitor (MCoTI-II, pdb: 1IB9) subfamilies. The sequence of kalata B8, a hybrid cyclotide isolated from the plant O. affinis is also shown. Conserved Cys and Asp/Asn (required for cyclization) residues are marked in yellow and light blue, respectively. Disulfide connectivities and backbone-cyclization are shown in red and a dark blue line, respectively. Molecular graphics were created using PyMol.

The main features of cyclotides are a remarkable stability due to the cystine knot,[10] a small size making them readily accessible to chemical synthesis,[11] recombinant expression using standard expression systems,[12] and an excellent tolerance to sequence variations.[9] For example, the first cyclotide to be discovered, kalata B1, is an orally effective uterotonic,[13] and other engineered cyclotides based on kalata B1 have also been shown to be orally bioactive.[14] In addition, some cyclotides can cross mammalian cell membranes[15] and are able to target intracellular protein interactions both in vitro and in vivo.[16] Cyclotides thus appear as promising leads or frameworks for the development of novel peptide-based diagnostics, therapeutics and research tools.[17] This article provides a brief overview of their properties and their potential use as molecular frameworks for the design of peptide-based diagnostic and therapeutic tools.

DISCOVERY

The discovery of the first cyclotide was accomplished in the late 1960s by a Norwegian doctor, Lorents Gran,[18] by studying an indigenous medicine in Africa that was used to accelerate childbirth. This traditional remedy was based on a medicinal herbal tea made by boiling in water the plant Oldelandia affinis (Rubiaceae family) from which the cyclotide kalata B1 originates, showing the stability of kalata B1 at high temperatures up to 100° C.[19] The active uterotonic component of the tea was found to be a peptide around 30 residues long that was called kalata B1. The sequence and structure of kalata B1, however, were not defined at that time given the limitations of the protein chemistry techniques available in the early 1970s.[18] It was not until 1995 when the Cys-knot backbone-cyclized nature of kalata B1 was first elucidated (Fig. 1).[13]

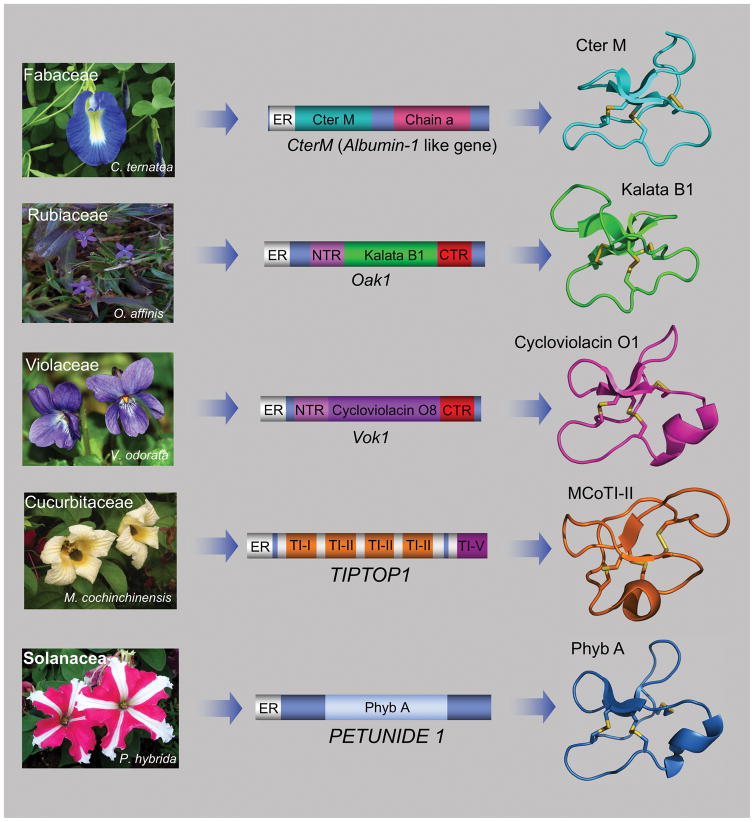

At about the same time, different research groups discovered several other macrocyclic peptides of similar size, sequence and structure that were isolated from plants of the Rubiaceae and Violaceae families (Fig. 1)[20] This led to the definition of the cyclotide family of proteins in 1999 based on their common backbone-cyclized Cys-knot topology and sequence homology.[21] Cyclotides have now been isolated from the Cucurbitaceae, Fabaceae, Solanaceae and Apocynaceae families in addition to Rubiaceae and Violaceae, with the latter two comprising the majority of known cyclotides (Fig. 2).[22]

Figure 2.

Genetic origin of cyclotides in plants. Rubiacea and Violaceae plants have dedicated genes for the production of cyclotides. The genes encode protein precursors containing an ER signal peptide, an N-terminal pro-region, the N-terminal repeat (NTR), the mature cyclotide domain and a C-terminal flanking region (CTR).[40] Cyclotides from the Fabaceae family of plants isolated recently from C. ternatea, are produced from precursor proteins containing an ER signal peptide immediately followed by the cyclotide domain, which is flanked at the C-terminus by a peptide linker and the albumin a-chain. In this case, the cyclotide domain replaces the albumin-1 b-chain.[7] Cyclotides from the trypsin inhibitor subfamily are produced from TIPTOP proteins, which contain a tandem series of cyclic trypsin inhibitors terminating with an acyclic trypsin inhibitor.[38b] The protein precursors for cyclotides from the Solanaceae family are encoded in genes similar to those found in the Rubiacea and Violaceae plants with dedicated precursor proteins that have an ER signal, a pro-region, the linear peptide precursor, and end with a hydrophobic tail.[45a] Cyclotides structures were generated using PyMol and the pdb codes: 2LAM (Cter M), 1NB1 (kalata B1), 1NBJ (cycloviolacin O1) and 1IB9 (MCoTI-II). The structure of cyclotide Phyb A was obtained by homology modeling using the structure of cycloviolacin O1 (pdb: 1NBJ) as template.

While most of the cyclotides come from the coffee and violet families, the distribution of cyclotides within these families is quite different. All of the plants studied from the violet family have been found to contain cyclotides, but only about 5% of plants from the coffee family that have been analyzed have shown to contain cyclotides.[22] Typically, a single plant contains multiple cyclotides (≈10–160), which are usually distributed across all tissues, including flowers, leaves, stems, roots, and in some cases even seeds.[23]

Initial efforts to discover cyclotides were almost exclusively based on the isolation of the cyclotides from the plant followed by chemical characterization of the corresponding peptides.[24] The use of modern chemical approaches has reduced the amount of plant material required for a full characterization of the cyclotides contained in the sample when compared to the early methods. For example, MALDI-TOF/TOF and LC-MS/MS techniques have been recently used for the efficient identification of cyclotides from very small plant samples (e.g. 1 cm2 of leaf tissue).[25] The recent combination of HPLC and MALDI-TOF with microwave-based extraction techniques has also been recently employed for the efficient isolation and characterization of cyclotides.[26]

The fact that cyclotides are ribosomally produced from genetically encoded protein precursors has also allowed the recent use of in silico screening approaches for the identification of cyclotides in plants.[27] For example, a recent pilot study was able to identify 145 unique cyclotide analogs from 30 different plant genomes comprising 10 families.[28] In a recent study, the use of in silico transcriptomic and proteomic screening identified 164 cyclotides in Viola tricolor, which led to the authors of this study to estimate the total number of cyclotides in the Violaceae family alone to be around 150,000.[29] In silico mining of genomes combined with molecular biology approaches has been used for the discovery of a large number of new ribosomal natural products, including cyclotides.[27] For example, database mining approaches were recently for the identification of cyclotide-like sequences in the plant Zea mays (maize), that were later confirmed to be expressed at the mRNA level in the root system of the plant.[30]

Combining the power of in silico mining of transcriptomes and/or genomes with high efficient chemical extraction and analysis protocols using HPLC and MALDI-TOF would probably be the ultimate preferred approach for high throughput discovery of novel cyclotide and related analogues. This approach was also recently employed for the rapid discovery of novel cyclotides.[31]

The CyBase database has recently been created to allow easy access to the large number of cyclotide sequences that have been found thus far.[32] This database can be accessed through a publicly available website (http://CyBase.org.au) and contains around 300 known cyclotides as well as several tools useful for their sequence analysis. CyBase also contains sequence information on other cyclic peptides produced from ribosomally-synthesized polypeptide precursors.

STRUCTURE

All naturally-occurring cyclotides range in size from 28 to 37 residues, contain six Cys residues and are backbone-cyclized (Fig. 1). The Cys residues are oxidized to form three disulfide bonds that adopt the cyclic cystine-knot topology, i.e. the disulfide bridges CysI-CysIV and CysII-CysV form a ladder arrangement with the disulfide bridge CysIII-CysVI running through them (Fig. 3A). The interlocking nature of cyclic cystine knot (CCK) motif makes the cyclotide backbone very compact providing a highly rigid structure.[33] As a result, cyclotides are extremely stable compounds, that have been shown to be resistant to thermal and chemical denaturation and to enzymatic degradation.[17a, 34] Proof of this extraordinary stability is evident from the discovery of the first cyclotide, kalata B1, which was able to remain structurally intact and biologically active after being extracted by boiling water to make a medicinal herbal tea.[18] Most linear peptides and proteins treated under the same conditions would not retain their native structure and consequently would lose their biological activity.

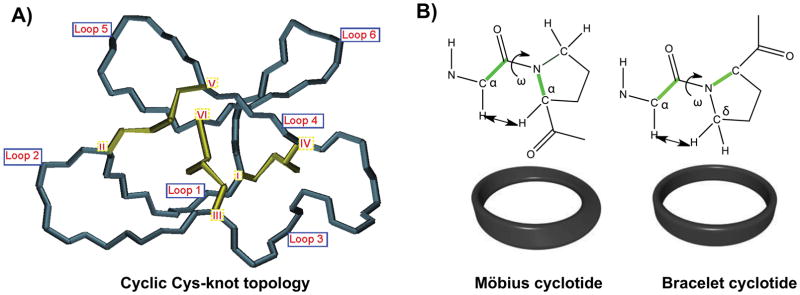

Figure 3.

General structural features of the cyclic cystine knot (CCK) topology found in all cyclotides. A. Detailed three-dimensional structure of the cyclic cystine knot (CCK) and the connecting loops found in cyclotides. The six Cys residues labeled I through VI whereas loops connecting the different Cys residues are designated as loop 1 through 6, in numerical order from the N- to the C-terminus. B. Möbius cyclotides contain a cis-Pro residue in loop 5 that induces a local 180° backbone twist, whereas bracelet cyclotides do not.

Cyclotides are classified into three subfamilies known as the Möbius, bracelet, and trypsin inhibitor cyclotide subfamilies.[35] Although all the subfamilies have the same cyclic Cys-knot topology, i.e. Cys disulfide connectivities, the composition of the loops is slightly different.

The Möbius subfamily of cyclotides, which includes kalata B1, contain a cis-Pro residue at loop 5 that results in a slight twist of the backbone, while bracelet cyclotides do not (Fig. 3B).[13] Bracelet cyclotides are slightly larger than Möbius cyclotides and are more structurally diverse. They are also much more numerous than Möbius cyclotides and make up approximately two-thirds of the sequenced cyclotides known.[36] Despite their numerical dominance, bracelet cyclotides are more difficult to fold in vitro than either Möbius or trypsin inhibitor cyclotides, thereby making them more challenging to synthesize chemically using standard peptide synthesis protocols. As a consequence, this type of cyclotides have been less used in the development of the biotechnological applications that will be described later in this article.

More recently, a novel suite of cyclotides possessing novel sequence features, including a lysine-rich nature, have been isolated from two species of Australasian plants from the Violaceae family.[37] These newly discovered cyclotides were found to bind to lipid membranes and were cytotoxic against cancer cell lines while showing low toxicity against red blood cells, which could be useful advantageous for potential therapeutic applications.

The trypsin inhibitor subfamily of cyclotides is the smallest of the three, consisting of only a small number of cyclotides isolated from the seeds of the plant Momocordica cochinchinesis (Cucurbitaceae family)[38] and are potent trypsin inhibitors.[23a] These cyclotides do not share significant sequence homology with the other cyclotides beyond the presence of the three-cystine bridges that adopt a similar backbone-cyclic cystine-knot topology (Fig. 1) and are more related to linear cystine-knot squash trypsin inhibitors. For this reason, they are also sometimes referred as cyclic knottins.[39] Cyclotides from this family possess a longer sequence in loop 1, making the Cys-knot slightly less rigid than in cyclotides from the other two subfamilies.

BIOSYNTHESIS OF CYCLOTIDES

Cyclotides are ribosomally produced via processing from dedicated genes that, in some cases, encode multiple copies of the same cyclotide, and in others, mixtures of different cyclotide sequences.[40] The first genes encoding cyclotide precursor proteins were discovered in the plant Oldenlandia affinis (Rubiaceae family) for the kalata cyclotides (Fig. 2).[41] The gene encoding the precursor protein of cyclotide kalata B1 (Oak 1) encodes a protein containing an endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-targeting sequence, a pro-region, a highly conserved N-terminal repeat (NTR) region, a mature cyclotide domain, and a hydrophobic C-terminal tail (Fig. 4).[42] Similar genes have also been found in other plants from the Violaceae family.[43] Since then, genes encoding cyclotide protein precursors have been found also in other plants from the Rubiaceae and Violaceae family.[44] More recently, cyclotide precursor genes have also been identified in plants from the Solanaceae, Fabaceae and Cucurbitaceae families (Fig. 2).[7, 38b, 45] These new genes provide novel protein precursor architectures, indicating a high diversity in the way cyclotides are produced in nature.

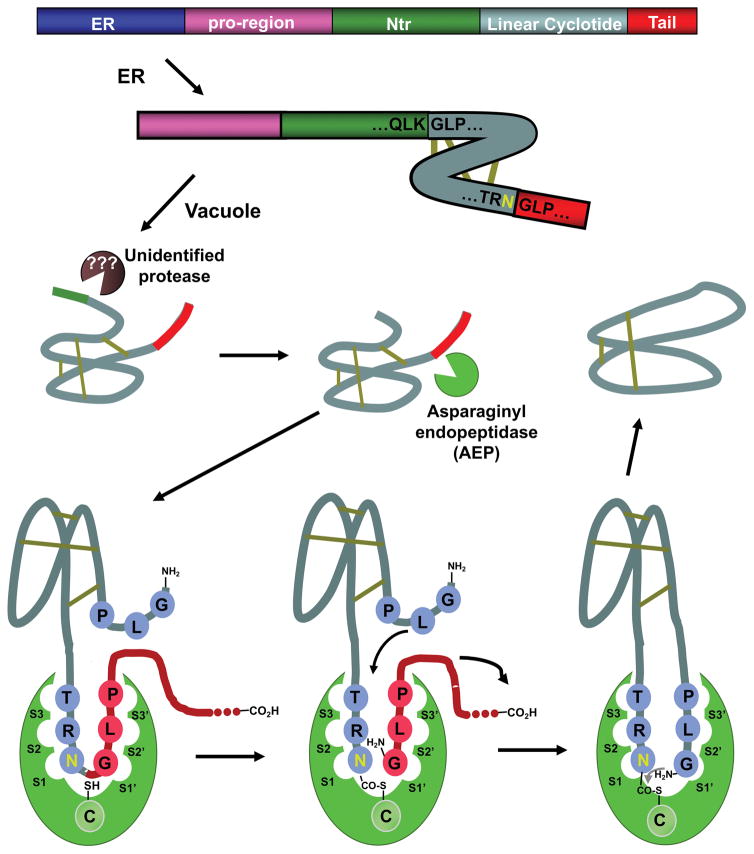

Figure 4.

Scheme showing the major steps thought to occur during the biosynthesis of cyclotides. The case for the processing of kalata B1 is shown. It has been proposed that the cyclization step is mediated by an asparaginyl endopeptidase (AEP), a common Cys protease found in plants. The cyclization takes place at the same time as the cleavage of the C-terminal pro-peptide from the cyclotide precursor protein through a transpeptidation reaction. The transpeptidation reaction involves an acyl-transfer step from the acyl-AEP intermediate to the N-terminal residue of the cyclotide domain.[40] The kalata B1 protein precursor contains an ER signal peptide, an N-terminal pro-region, the N-terminal repeat (NTR), the mature cyclotide domain and a C-terminal flanking region (tail, also known as CTR).

The complete mechanism of how cyclotide precursors are processed and cyclized has not been completely elucidated yet (Fig. 4). However, recent studies indicate that an asparaginyl endopeptidase (AEP)-like ligase is a key element in the C-terminal cleavage and cyclization of cyclotides. The transpeptidation reaction involves an acyl-transfer step from the acyl-AEP intermediate to the N-terminal residue of the cyclotide domain.[46] AEPs are Cys proteases that are very common in plants and specifically cleave the peptide bond at the C-terminus of Asn and, less efficiently, Asp residues. All of the cyclotide precursors identified so far contain a well-conserved Asn/Asp residue at the C-terminus of the cyclotide domain in loop 6, which is consistent with the role of AEPs in the cleavage/cyclization step. In agreement with this, a recent study has shown that AEP-like enzymes are required for the production of mature cyclotides from O. affinis. The AEP-like enzyme rOaAEP1b, cloned from the O. affinis genome, was recombinantly produced and was shown to efficiently ligate the C and N-termini of an N-terminal cleaved cyclotide precursor.[47] Independently, another AEP-like ligase, called butelase-1, has recently been isolated from the cyclotide producing plant Clitoria ternatea. This ligase showed efficient capabilities in cyclizing various peptides, including linear cyclotide precursors containing the C-terminal recognitions sequence.[48] Despite the significant progress done on understanding at the mechanistic level of how cyclotides are produced in plants, there is still is not too much known about the N-terminal cleavage process and the protease involved at that step.

CHEMICAL PRODUCTION OF CYCLOTIDES

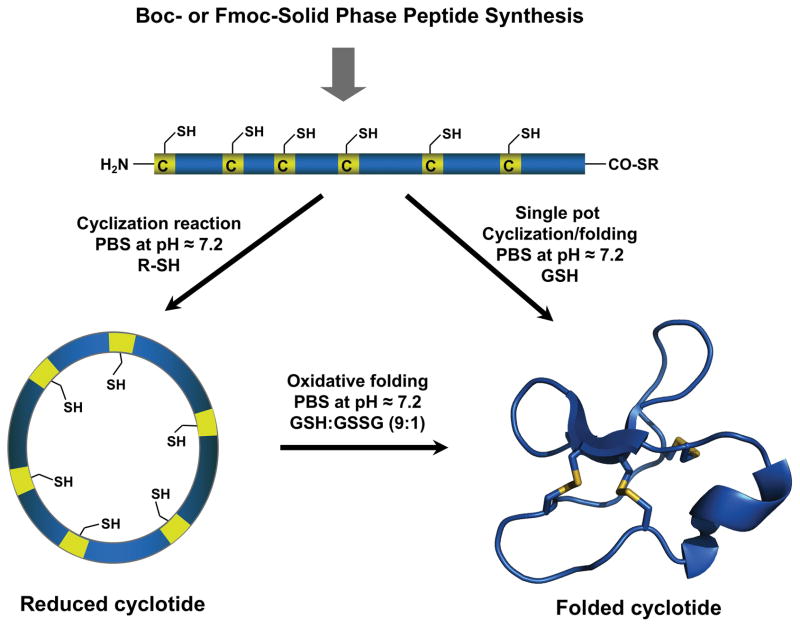

Cyclotides are relatively small polypeptides, ≈30–40 amino acids long, and therefore the linear precursors can be readily synthesized by chemical methods using solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS).[49] Backbone cyclization of the corresponding linear precursor can be readily accomplished in aqueous buffers under physiological conditions by using an intramolecular version of native chemical ligation (NCL)[50] on linear precursors containing an N-terminal cysteine and an -thioester group at the C-terminus (Fig. 5).[51] Peptide α-thioesters can be easily generated using standard solid-phase peptide synthesis approaches using either Boc- or Fmoc-based chemistry.[11] Once the peptide is cleaved from the resin, the linear cyclotide precursors can be cyclized and folded sequentially. More recently, it has been shown that the cyclization and folding can be carried out in a ‘single pot’ reaction by using glutathione (GSH) as a thiol additive.[52] This approach has successfully been used to chemically generate many native and engineered cyclotides (for a recent review in this topic see[11]).

Figure 5.

Chemical synthesis of cyclotides by means of an intramolecular native chemical ligation (NCL). This approach requires the chemical synthesis of a linear precursor bearing an N-terminal Cys residue and an α-thioester moiety at the C-terminus. The linear precursor can be cyclized first under reductive conditions and then folded using a redox buffer containing reduced and oxidized glutathione (GSH).[11] Alternatively, the cyclization and folding can be efficiently accomplished in a ‘single pot’ reaction when the cyclization is carried out in the presence of reduced GSH as the thiol cofactor.[11]

Cyclotides can also be produced by chemoenzymatic cyclization of the corresponding synthetic linear precursors using AEP-like ligases as mentioned earlier.[47–48] These enzymes do not require the cyclotide linear precursor to be natively folded for the cyclization step to proceed efficiently.[48] The serine protease trypsin has also been used to produce several cyclotides based on the naturally occurring trypsin inhibitor cyclotide MCoTI-II.[53] In this work, folded linear cyclotide precursors bearing the P1 and P1′ residues at the C- and N-termini respectively were used as a viable substrate for trypsin-mediated cyclization, thus enabling synthesis of the cyclic backbone without the need for a C-terminal α-thioester. The use of trypsin-mediated cyclization provides a very efficient route for obtaining cyclotides with trypsin inhibitory properties. It should be noted, however, that although the cyclization yield can be extremely efficient (≈92% for naturally-occurring cyclotide MCoTI-II), the introduction of mutations that affect the binding to the proteolytic enzyme may affect the cyclization yield.[9a]

Transpeptidases like sortase A (SrtA) can also be used for the production of cyclotides from synthetic linear precursors.[54] It is worth noting, however, that due to the sequence requirements for SrtA, the heptapeptide motif (LPVTGGG) is left at the ligation site, and this should be considered when producing biologically active cyclotides.

RECOMBINANT EXPRESSION OF CYCLOTIDES

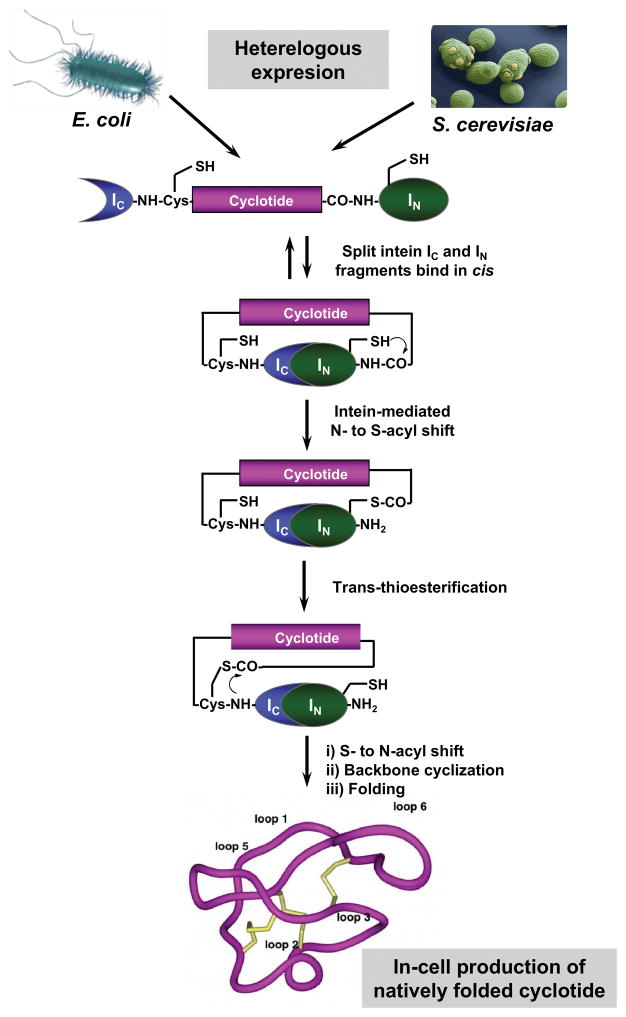

Recent advances in the fields of protein engineering and molecular biology make possible the biological synthesis of backbone-cyclized polypeptides using standard heterologous expression systems (for a recent review in this topic see[11]). The discovery of intein-mediated protein splicing both in cis and trans has made possible the generation of backbone-cyclized polypeptides using standard expression systems (Fig. 6). Our group pioneered the use of intein-mediated backbone cyclization for the biosynthesis of fully folded cyclotides inside bacterial cells using heterologous expression systems.[9a, 55] This initial approach used an intramolecular version of intein-mediated ligation (also called Expressed Protein Ligation (EPL)).[12] This cyclization method has also been successfully used for the recombinant expression of other naturally occurring disulfide-rich backbone-cyclized polypeptides such as the Bowman-Birk inhibitor SFTI-1 and several θ-defensins.[9a, 56]

Figure 6.

Heterologous expression of cyclotides by protein trans-splicing (PTS).57–58] In this approach the linear cyclotide precursor is fused in-frame at the C- and N-termini directly to the IN and IC polypeptides of the Npu DnaE split intein. None of the additional native C- or N-extein residues were added in this construct. In this work, the native Cys residue located at the beginning of loop 6 of MCoTI-I was used to facilitate backbone cyclization. The N- and C-termini of the linear cyclotide precursor are linked together through a native peptide bond through a transpeptidation reaction mediated by the self-processing domains of the split intein. This approach has been successfully used for the production of bioactive cyclotides in eukaryotic and prokaryotic expression systems.[57–58]

Backbone cyclization using intein-mediated protein trans-splicing (PTS) has also been reported for the efficient production of naturally-occurring and engineered cyclotides in prokaryotic and eukaryotic expression systems (Fig. 6).[57] In-cell expression of folded cyclotides is quite efficient at being able to provide intracellular concentrations in the range of 20–40 μM, which are appropriate for performing in-cell screening.[57] This level of expression in E. coli equals to ≈10 mg of folded cyclotide per 100 g of wet cells.[58] More importantly, in-cell production makes possible the generation of large genetically-encoded libraries of cyclotides inside live cells that can be rapidly screened for the selection of novel sequences able to modulate or inhibit the biological activities of particular biomolecular targets.[57b]

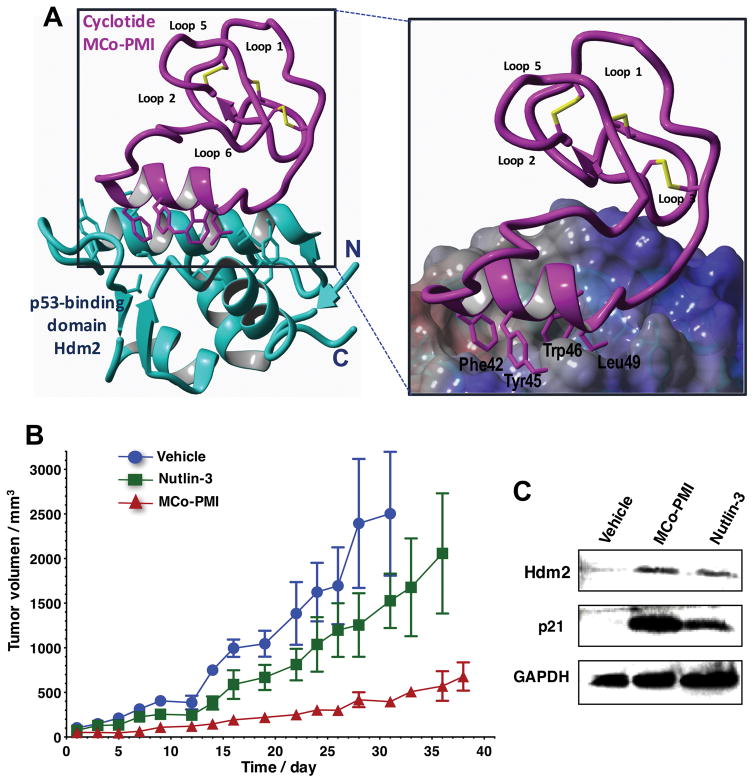

The recombinant production of cyclotides facilitates the production of cyclotides labeled with NMR active isotopes such as 15N and/or 13C in a very inexpensive fashion.[33, 59] Having access to 15N and/or 13C-labeled cyclotides facilitates the use of heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy to study structure-activity relationships of any biologically active cyclotides and their molecular targets. This was recently demonstrated in the structural studies carried out on a cyclotide engineered to bind the p53 binding domain of the E3-ligases Hdm2 and HdmX (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Structure and in vivo activity of the first cyclotide designed to antagonize an intracellular protein-protein interaction in vivo.[16] A. Solution structure of an engineered cyclotide MCo-PMI (magenta) and its intracellular molecular target, the p53 binding domain of oncogene Hdm2 (blue). The cyclotide binds with low nM affinity to both the p53-binding domains of Hdm2 and HdmX. The overexpression of these two proteins Hdm2 and HdmX is a common mechanism used by many tumor cells to inactive the p53 tumor suppressor pathway promoting cell survival. Targeting Hdm2 and HdmX has emerged as a validated therapeutic strategy for treating cancers with wild-type p53. B. Cyclotide MCo-PMI activates the p53 tumor suppressor pathway and blocks tumor growth in a human colorectal carcinoma xenograft mouse model. HCT116 p53+/+ xenografts mice were treated with vehicle (5% dextrose in water), nutlin 3 (10 mg/kg) or cyclotide (40 mg/kg, 7.6 mmol/kg) by intravenous injection daily for up to 38 days. Tumor volume was monitored by caliper measurement. C. Tumors samples were also subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by western blotting for p53, Hdm2 and p21, indicating activation of p53 on tumor tissue.

PTS has also been successfully used in the production of other Cys-rich backbone-cyclized polypeptides.[60]

BIOLOGICAL ACTIVITIES OF NATURALLY-OCCURRING CYCLOTIDES

The biological function of the naturally-occurring cyclotides of the Möbius and bracelet sub-families in plants seems to be primarily as host-defense agents as deduced from their activity against insects.[7, 41, 61] Cyclotides have been shown to efficiently inhibit the growth and development of nematodes and trematodes[62] and of mollusks.[63]

Cyclotides seem to exert their biological activity by interacting with cellular membranes and disrupting their normal function. For example, the midgut membranes of Lepidopteran species are severely disrupted after ingesting cyclotides.[64] The molecular mechanism of how cyclotides disrupt cellular membranes has been widely studied, and at least for cyclotide kalata B1, it is well established that the first step involves the specific binding of the cyclotide to the phosphatidylethanolamine phospholipids present in the cellular membrane.[65] This initial binding step causes internalization of the cyclotide into the membrane, compromising its physical integrity and triggering the formation of pores and/or leakage of cell contents.[66] Aside from their insecticidal and nematocidal activities, cyclotides have also been shown to have potential pharmacologically relevant activities, which include antimicrobial and anti-tumor activities.

Cyclotides from the Möbius and bracelet sub-families have hydrophobic and hydrophilic patches located in different regions of their surface, resembling to some extent the amphipathic character of classical antimicrobial peptides. For example, the cyclotide kalata B1 has been found to have antimicrobial activity against Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria.[67] Similar antibacterial activities have been found in cyclotides isolated from Hedyota biflora (Rubiaceae family)[68] and C. ternatea (Fabaceae family).[45b] The most active antimicrobial cyclotide tested so far seems to be the bracelet cyclotide cycloviolacin O2,[69]which has been shown to have antimicrobial activity against Staphylococcus aureus in a mouse infection model.[70] It is worth noting, however, that the antimicrobial activity of cyclotides when tested in vitro seems to occur only under non-physiological conditions involving the use of low ionic strength buffers, which seriously limits its potential on the design of antimicrobial therapeutics.

The anti-HIV activity of cyclotides has been one of the most extensively studied so far due to its potential pharmacological applications.[20a, 71] Gustafson and co-workers reported the first cyclotides with anti-HIV activity as part of a screening program to identify novel natural antiviral compounds.[71a, 72] More recently, several other cyclotides from the bracelet and Möbius subfamilies were also shown to have anti-HIV activity.[71c, 71d]

Although the exact molecular mechanism of action is not fully understood, the inability of cyclotides to inhibit HIV reverse transcriptase activity seems to suggest that the antiviral activity occurs before the entry of the virus into the host cell.[20a] Recent studies have also shown a correlation between the hydrophobic character of cyclotides and their anti-HIV activities.[71d, 73] The fact that cyclotides can bind phospholipids present in the cellular membrane may suggest that the probable mode of anti-HIV activity could happen through a mechanism that affects the binding and/or fusion of the virus to the cellular membrane. However, it is unclear if the cyclotide activity could be the result of binding to the host cell membrane, to the viral envelope, or to both.

Several cyclotides have been reported to have selective cytotoxicity against several cancer cell lines, including primary cancer cell lines, when compared to normal cells.[74] More recently, the cytotoxic activity of cyclotide vingo 5 from Viola ignobilis has been shown to be apoptosis-dependent when tested in HeLa cells.[75] In addition, three new cyclotides isolated from Hedyotis diffusa, a Chinese medicinal plant from the Rubiaceae family, have been shown to induce apoptosis and inhibit proliferation and migration of several prostate cancer cell lines.[76] Cyclotide DC3, the most active of the three, was able to inhibit tumor growth in a mouse xenograft model. Similar cytotoxic activities have been also reported in vitro against MCF-7 (breast cracinoma) and Caco-2 (colorectal adenocarcinoma) cells with acyclic cyclotides isolated from the plant Palicourea rigida.[77]

Overall, the therapeutic index (i.e. the ratio between the dose required for therapeutic effects versus toxic effects on normal cells) of cytotoxic cyclotides is not very high, and therefore will require optimization before they can be developed into effective anti-cancer agents.

More recently, the molecular targets of labour-accelerating cyclotide kalata B7 and engineered analogs was found to be the G protein-coupled oxytocin and vasopressin V1a receptors.[78]

ENGINEERED CYCLOTIDES WITH NOVEL BIOLOGICAL ACTIVIES

The unique properties associated with the cyclotide scaffold make them extremely valuable in the development of novel peptide-based therapeutics (see Table 1).[17] As mentioned earlier, the CCK framework provides cyclotides with a compact and a highly rigid structure that gives them an exceptional resistance to chemical, physical and biological degradation. The cyclotide scaffold also shows very high tolerance to mutations making them an ideal molecular framework for molecular grafting and evolution for the generation of novel cyclotides with new biological activities. In addition, cyclotides from the trypsin inhibitor subfamily are not toxic to mammalian cells up to concentrations of 100 μM[16] and have been shown to be able to cross cellular membranes[15] to target intracellular cytosolic protein-protein interactions.[16]

Table 1.

Summary of work published in engineered cyclotides and linear cyclotides/knottins with novel biological activities leading to therapeutic and bioimaging applications.

| Cyclotide | Biological activity | Loop Modified | Application | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Möbius subfamily | ||||

|

| ||||

| Kalata B1 | VEGF-A antagonist | 2, 3, 5 & 6 | Anti-angiogenic, potential anti-cancer activity | [79a] |

| Kalata B1 | Dengue NS2B-NS3 Protease inhibitor | 2 & 5 | Anti-viral for Dengue virus infections | [98] |

| Kalata B1 | Bradikynin B1 receptor antagonist | 6 | Chronic and inflammatory pain | [14] |

| Kalata B1 | Melanocortin 4 receptor Agonist | 6 | Obesity | [80] |

| Kalata B1 | Neuropilin-1/2 antagonist | 5 & 6 | Inhibition of endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis | [99] |

| Kalata B1 | Immunomodulator | 5 & 6 | Protecting against multiple sclerosis | [87] |

| Kalata B1 | Immunomodulator | 4 | Protecting against multiple Sclerosis | [100] |

|

| ||||

| Trypsin inhibitor subfamily | ||||

|

| ||||

| MCoTI-I | CXCR4 antagonist | 6 | Anti-metastatic and anti-HIV | [52, 81] |

| MCoTI-I | p53-Hdm2/HdmX Antagonist | 6 | Anti-tumor by activation of p53 pathway | [16] |

| MCoTI-II | FMDV 3C protease Inhibitor | 1 | Antiviral for foot-and-mouth disease | [53] |

| MCoTI-II | β-Tryptase inhibitor | 3, 5 & 6 | Inflammation disorders | [85] |

| MCoTI-II | β-Tryptase inhibitor Human elastase inhibitor |

1 | Inflammation disorders | [79b] |

| MCoTI-II | CTLA-4 antagonist | 1,3 & 6 | Immunotherapy for cancer | [101] |

| MCoTI-II | Tryptase inhibitor | 1 | Anticancer | [102] |

| MCoTI-II | VEGF receptor agonist | 6 | Wound healing and cardiovascular damage | [103] |

| MCoTI-I | α-Synuclein-induced cytotoxicity inhibitor | 6 | Parkinson’s disease Validate phenotypic screening of genetically-encoded cyclotide libraries |

[57b] |

| MCoTI-II | BCR-Abl kinase Inhibitor | 1 & 6 | Chronic myeloid leukemia Attempt to graft both a cell penetrating peptide and kinase inhibitor |

[104] |

| MCoTI-I | MAS1 receptor agonist | 6 | Lung cancer and myocardial infarction | [105] |

| MCoTI-II | SET antagonist | 6 | Potential anticancer | [88] |

| MCoTI-II | FXIIa and FXa inhibitors | 1 & 6 | Antithrombotic and cardiovascular disease | [106] |

| MCoTI-II | Thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) agonist | 6 | Microvascular endothelial cell migration inhibition Anti-angiogenesis | [107] |

| MCoTI-II | Antiangiogenic | 5 & 6 | Anti-cancer | [108] |

|

| ||||

| Linear trypsin inhibitor (acyclic cyclotide/linear knottin) subfamily | ||||

|

| ||||

| EETI | integrin-binding knottin conjugated with contrast microbubles | 1a | Ultrasound imaging of tumor angiogenesis | [93] |

| EETI | Fluorescence-labeled integrin-binding knottin | 1a | PET imaging Localizes in mouse medulloblastoma |

[92] |

| EETI | 64Cu-labeled integrin- binding knottin | 1 & 5a | PET probe for atherosclerosis imaging | [94] |

| EETI | 18F-labeled integrin- binding knottin | 1 & 5a | PET probe for angiogenesis imaging | [94] |

| EETI | 99Tc-labeled integrin-binding knottin | 1,3 & 5a | SPECT agent for imaging integrin αvβ6 | [95] |

| EETI | 177Lu-labeled integrin- binding knottin | 1a | SPECT agent for radionuclide therapy of integrin-positive tumors | [95] |

Loop numbering in EETI is based on sequence homology to the cyclotide MCoTI-I.

The pharmacologic potential of grafted cyclotides was first demonstrated in two early studies aimed to develop novel anti-cancer[79] and anti-viral peptide-based therapeutics.[53] Tumor growth is usually associated with unregulated angiogenesis, and therefore molecules with anti-angiogenic activity have potential applications in cancer treatment. The molecular grafting of an Arg-rich peptide antagonist for the interaction of vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) and its receptor into several loops of cyclotide kalata B1 yielded cyclotides with anti-VEGF activity.[79a] The cyclotide grafted into loop 3 showed the highest activity in blocking VEGF-A receptor binding (IC50 ≈ 12 μM). Although this is the first example of a successful functional redesign of a cyclotide, it should be noted that the biological activity would still need to be improved by several orders of magnitude for a potential pharmacological application in vivo. A similar approach has been used more recently for targeting the bradykinin and melanocortin 4 receptors for pain and obesity management, respectively.[14, 80] It is worth noting that the kalata B1-based bradykinin antagonist was shown to be orally bioavailable[14] highlighting the potential of the cyclotide scaffold for the development of orally-bioavailable peptide-based therapeutics. The cyclotide MCoTI-I has been recently used for the design of a potent (low nM) CXCR4 antagonist.[81] The cytokine receptor CXCR4 has been associated with multiple types of cancers where its overexpression/activation promotes metastasis, angiogenesis, and tumor growth and/or survival.[82]

Proteases are well-recognized drug targets as they are involved human diseases including microbial/viral infectivity, in viral and microbial infectivity.[83] In addition, many human diseases including inflammatory and pulmonary diseases, cancer, cardiovascular and neurodegenerative conditions have been associated with abnormal expression levels of proteases.[84] The trypsin inhibitor subfamily of cyclotides has been used for the design for protease inhibitors with pharmacological relevance. For example, a mutated version of cyclotide MCoTI-II was transformed into a potent and selective foot-and-mouth-disease (FMDV) 3C protease inhibitor.[53] The same scaffold has also been used in the development of β-tryptase and human leukocyte elastase inhibitors with low nM Ki values.[79b, 85] These proteases are validated targets for inflammatory disorders.

In a recent work, a point mutated cyclotide kalata B1 T20K was reported to have oral activity in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis.[86] The potential of grafted cyclotides in the context of multiple sclerosis has been also explored by grafting peptide sequences from the MOG35-55 epitope onto the cyclotide kalata B1.[87]

One of the most exciting features of the cyclotide scaffold is that some cyclotides, in particular those from the trypsin inhibitor subfamily, are able to penetrate cells. This exciting finding makes possible the delivery of biologically active cyclotides using grafted MCoTI-based cyclotides to target intracellular protein-protein interactions. For example, we have recently used cyclotide MCoTI-I to produce a potent inhibitor for the interaction between p53 and the proteins Hdm2/HdmX (Fig. 7).[16] The resulting cyclotide MCo-PMI was able to bind with low nanomolar affinity to both Hdm2 and HdmX, showed high stability in human serum, and was cytotoxic to wild-type p53 cancer cell lines by activating the p53 tumor suppressor pathway both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 7).[16] This work constitutes the first example where an engineered cyclotide was able to target an intracellular protein-protein interaction in an animal model of human colon carcinoma highlighting the therapeutic potential of MCoTI-cyclotides for targeting intracellular protein-protein interactions. A similar approach, but employing cyclotide MCoTI-II instead, has been also used to produce a grafted cyclotide able to antagonize the SET protein, which is overexpressed in some human cancers.[88]

We have recently reported an MCoTI-grafted cyclotide (MCoCP4) that was able to inhibit α-synuclein-induced cytotoxicity in yeast S. cerevisiae.[57b] This was accomplished by grafting the sequence of cyclic peptide CP4 (cyclo-CLATWAVG), which was recently shown to reduce α-synuclein-induced cytotoxicity in a yeast,[89] into the loop 6 of MCoTI-I. α-Synuclein is a small lipid-binding protein that is prone to misfolding and aggregation, that has been linked to Parkinson’s disease by genetic evidence and its abundance in the Parkinson’s disease-associated intracellular aggregates known as Lewy bodies, and therefore it is a validated therapeutic target for Parkinson’s disease.

Given the good in vivo biological activity of MCoTI-cyclotides, the biodistribution and potential to cross the blood brain barrier of these cyclotides have recently been studied.[90] In this work, it was confirmed that cyclotide MCoTI-II is distributed predominantly to the serum and kidneys, confirming that they are stable in serum and suggesting that they are eliminated from the blood through renal clearance. In addition, this work also showed that although MCoTI-cyclotides have cell-penetrating properties and can modulate intracellular protein/protein interactions, cyclotide MCoTI-II showed no significant uptake into the brain.

SCREENING OF CYCLOTIDE-BASED LIBRARIES

The ability to produce natively folded cyclotides in vivo[55b, 57b, 91] discussed earlier opens up the intriguing possibility of generating large libraries of genetically-encoded cyclotides, potentially containing billions of members. This tremendous molecular diversity should allow the selection of strategies that mimic the evolutionary processes found in nature to select novel cyclotide sequences able to target specific molecular targets. As a proof of principle, we used this approach for the production of a genetically-encoded library of MCoTI-I based cyclotides. The library was designed to mutate every single amino acid in loops 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 to explore the effects on folding and trypsin binding activity of the resulting mutants.[55b] Interestingly, only two mutations (G27P and I22G) out of the 26 substitutions studied were able to negatively affect the folding of the resulting cyclotides. Although these two mutants were not able to fold efficiently, their natively folded form was still able to bind trypsin. The rest of the mutants were able to cyclize and fold with similar yields to that of the wild-type cyclotide, emphasizing the high plasticity and sequence tolerance of MCoTI-based cyclotides.[55b]

More recently, we have shown that cyclotide-based libraries can be also used for phenotypic screening in eukaryotic cells.[57b] In this work, an engineered cyclotide (MCoCP4) that was designed to reduce toxicity of human α-synuclein in live yeast cells was selected by phenotypic screening from cells transformed with a mixture of plasmids encoding MCoCP4 and inactive cyclotide MCoTI-I in a ratio of 1 to 50,000. These exciting results demonstrate the potential to perform phenotypic screening of genetically encoded cyclotide-based libraries in eukaryotic cells for the rapid selection of novel bioactive cyclotides. In addition, expression in eukaryotic systems should allow the production of cyclotides with different post-translational modifications not available in bacterial expression systems.

The recent development of efficient approaches for the chemical synthesis, cyclization and folding of cyclotide-based libraries is allowing for the first time to perform high throughput screening on chemically-generated libraries of cyclotides.[52] We have recently demonstrated that bioactive folded MCoTI-based cyclotides can be efficiently produced in parallel using a ‘tea-bag’ approach in combination with high efficient cyclization-folding protocols.[52] The approach described in this work also includes an efficient purification procedure to rapidly remove non-folded or partially folded cyclotides from the cyclization-folding crude. This procedure can easily be used in parallel for the purification of individual compounds, but also and more importantly, for the purification of cyclotide mixtures, therefore making it compatible with the synthesis of amino acid and positional scanning libraries to perform efficient screening of large chemical-generated libraries. A similar approach was recently used to produce a potent anthrax lethal factor protease inhibitor using the Cys-rich backbone-cyclized θ-defensin RTD-1.[60b]

CYCLOTIDES AS MOLECULAR IMAGING PROBES

The development of adequate diagnostic molecular tools is key for early detection and monitoring in the successful treatment of many diseases, including cancer.[5] Over the past two decades, technological advances in imaging instrumentation has dramatically increased the capabilities for bioimaging and fueling the need for developing improved molecular imaging agents. Ideally, improved imaging agents should provide high affinity and selectivity for the corresponding molecular marker and greater stability. To achieve optimal contrast between healthy and diseased tissues, molecular agents should have affinities in low nM to pM range, high selectivity over healthy tissue, rapid clearance from healthy tissue to reduce background signal, and high chemical and biological stability.

Properly functionalized engineered linear squash trypsin inhibitors, which share sequence homology and structure with the trypsin inhibitor subfamily of cyclotides but are not backbone-cyclized, have been shown to be excellent bio-imaging and detection tools in cancer (recently reviewed in [5]). Integrin-binding variants based on the Ecballium elaterium trypsin inhibitor II (EETI) have been extensively used as bio-imaging agents (Table 1). They have been shown to provide significant tumor accumulation and low imaging signals in kidney, liver, and other organs. For example, an Alexa-Fluor 680 dye-conjugated integrin-targeting EETI variant has been shown to localize to intracranial medulloblastoma in mice after intravenous injection.[92] An Integrin-targeting EETI variant conjugated to a contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging contrast agent has been also used for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).[93] Different integrin-binding EETI variants labeled with 18F and 64Cu radionuclides have been used for positron emission tomography (PET) imaging,[94] while 99Tc and 177Lu were used for single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).[95]

There are still no published reports on using cyclotides as imaging agents. However, given the similar characteristics in sequence and structure (except for the head-to-tail cyclization) of the trypsin inhibitor cyclotides with the linear squash trypsin inhibitors described above, it is quite likely that this subfamily of cyclotides could be used for the development of excellent imaging reagents. Cyclotides from this family are not toxic to mammalian cells, do not interact with membranes and can be easily engineered to introduce novel biological functions. For example, our group has recently designed a cyclotide using the trypsin inhibitor cyclotide MCoTI-I that was able to antagonize the cytokine G-protein couple receptor CXCR4 with low nM affinity.[81] Overexpression of the CXCR4 in cancer cells is often correlated with a propensity for metastasis and poor prognosis,[96] and it has been proposed as a molecular biomarker for the development of diagnostic agents for therapeutic guidance and monitoring of cancer metastasis.[97] Hence, the development of cyclotide-based specific CXCR4 imaging agents should be feasible.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Cyclotides are now starting to be a well-studied family of micro-proteins that given their unique properties are also starting to gain acceptance as molecular scaffolds for the potential design of novel peptide-based therapeutics. Their unique circular backbone topology and knotted arrangement of three disulfide bonds provides a compact, highly rigid structure which confers exceptional resistance to thermal/chemical denaturation, and enzymatic degradation. Cyclotides have been shown to be able to cross human cell membranes and be able to target efficiently protein-protein interactions in vitro but also and more importantly in animal models. The fact that cyclotides can target intracellular targets in vivo highlights the high stability of the Cys-knot to be degraded/oxidized under complex biological conditions. The relative small size of cyclotides also makes them readily available by chemical synthesis allowing introduction of chemical modifications such as non-natural amino acids and PEGylation to improve their pharmacological properties. Cyclotides can also be expressed in several heterologous expression systems, and are amenable to substantial sequence variation, what makes them ideal substrates for molecular evolution strategies to enable generation and selection of compounds with optimal binding and inhibitory characteristics. Altogether, these unique characteristics for a polypeptide make them promising leads or frameworks for peptide drug design.

Although no cyclotides have reached human clinical trials yet, the results obtained with several bioactive cyclotides in animal models hint that this may occur in a not too distant future. One the main challenges that affect cyclotides, if they want to compete with small-molecule therapeutics, is their oral bioavailability. Some cyclotides have shown to be orally active but little information is available about their oral bioavailability. It is anticipated that more studies on the biopharmaceutical properties of these interesting micro-proteins will be available in the coming years.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Research Grant R01-GM113363 (J.A.C.).

Biographies

Andrew Gould received his Bachelor’s degree in chemistry from University of California at Irvine (UCI). He joined Dr. Camarero research group at the University of Southern Califonia, Los Angeles, in 2010 as graduate student, we he obtained his PhD in Pharmacology in 2016.

Andrew Gould received his Bachelor’s degree in chemistry from University of California at Irvine (UCI). He joined Dr. Camarero research group at the University of Southern Califonia, Los Angeles, in 2010 as graduate student, we he obtained his PhD in Pharmacology in 2016.

Julio A. Camarero started his studies in chemistry at the University if Barcelona (Spain), where he received his Master degree in 1992, and finished his PhD thesis in 1996. Afterwards he joined the group of Professor Tom W. Muir at The Rockefeller University as a Burroughs Wellcome Fellow. In 2000, he moved to the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory as a Distinguished Lawrence Fellow where he became staff scientist and head of laboratory in 2003. He joined the University of Southern California in 2007 as an associate professor, and became full professor in 2016.

Julio A. Camarero started his studies in chemistry at the University if Barcelona (Spain), where he received his Master degree in 1992, and finished his PhD thesis in 1996. Afterwards he joined the group of Professor Tom W. Muir at The Rockefeller University as a Burroughs Wellcome Fellow. In 2000, he moved to the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory as a Distinguished Lawrence Fellow where he became staff scientist and head of laboratory in 2003. He joined the University of Southern California in 2007 as an associate professor, and became full professor in 2016.

References

- 1.Abecasis GR, Auton A, Brooks LD, DePristo MA, Durbin RM, Handsaker RE, Kang HM, Marth GT, McVean GA. Nature. 2012;491:56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Lage K Genomes Project C. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842:1971–1980. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Petta I, Lievens S, Libert C, Tavernier J, De Bosscher K. Mol Ther. 2016;24:707–718. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Pluckthun A. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;55:489–511. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Liu H, Saxena A, Sidhu SS, Wu D. Front Immunol. 2017;8:38. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Krah S, Schroter C, Zielonka S, Empting M, Valldorf B, Kolmar H. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2016;38:21–28. doi: 10.3109/08923973.2015.1102934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Kintzing JR, Filsinger Interrante MV, Cochran JR. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2016;37:993–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGregor DP. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:616–619. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kintzing JR, Cochran JR. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2016;34:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Wang CC, Chen JJ, Yang PC. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2006;10:253–266. doi: 10.1517/14728222.10.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Camarero JA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:10025–10026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107849108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poth AG, Colgrave ML, Lyons RE, Daly NL, Craik DJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:1027–1032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103660108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gould A, Ji Y, Aboye TL, Camarero JA. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:4294–4307. doi: 10.2174/138161211798999438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Austin J, Kimura RH, Woo YH, Camarero JA. Amino Acids. 2010;38:1313–1322. doi: 10.1007/s00726-009-0338-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Huang YH, Colgrave ML, Clark RJ, Kotze AC, Craik DJ. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:10797–10805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.089854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Simonsen SM, Sando L, Rosengren KJ, Wang CK, Colgrave ML, Daly NL, Craik DJ. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:9805–9813. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709303200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Craik DJ, Du J. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2017;38:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2017.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Y, Bi T, Camarero JA. Adv Bot Res. 2015;76:271–303. doi: 10.1016/bs.abr.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aboye TL, Camarero JA. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:27026–27032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.305508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saether O, Craik DJ, Campbell ID, Sletten K, Juul J, Norman DG. Biochemistry. 1995;34:4147–4158. doi: 10.1021/bi00013a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong CT, Rowlands DK, Wong CH, Lo TW, Nguyen GK, Li HY, Tam JP. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:5620–5624. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Cascales L, Henriques ST, Kerr MC, Huang YH, Sweet MJ, Daly NL, Craik DJ. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:36932–36943. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.264424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Contreras J, Elnagar AY, Hamm-Alvarez SF, Camarero JA. J Control Release. 2011;155:134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ji Y, Majumder S, Millard M, Borra R, Bi T, Elnagar AY, Neamati N, Shekhtman A, Camarero JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:11623–11633. doi: 10.1021/ja405108p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a) Garcia AE, Camarero JA. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2010;3:153–163. doi: 10.2174/1874467211003030153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Henriques ST, Craik DJ. Drug Discov Today. 2010;15:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gran L. Lloydia. 1973;36:174–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gran L. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh) 1973;33:400–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1973.tb01541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.a) Gustafson KR, Sowder RC, Louis E, Henderson LE, Parsons IC, Kashman Y, Cardellina JH, McMahon JB, Buckheit RW, Pannell LK, Boyd MR. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:9337–9338. [Google Scholar]; b) Witherup KM, Bogusky MJ, Anderson PS, Ramjit H, Ransom RW, Wood T, Sardana M. J Nat Prod. 1994;57:1619–1625. doi: 10.1021/np50114a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Schöpke T, Hasan Agha MI, Kraft R, Otto A, Hiller K. Sci Pharm. 1993;61:145–153. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Craik DJ, Daly NL, Bond T, Waine C. J Mol Biol. 1999;294:1327–1336. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gruber CW, Elliott AG, Ireland DC, Delprete PG, Dessein S, Goransson U, Trabi M, Wang CK, Kinghorn AB, Robbrecht E, Craik DJ. Plant Cell. 2008;20:2471–2483. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.062331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.a) Hernandez JF, Gagnon J, Chiche L, Nguyen TM, Andrieu JP, Heitz A, Trinh Hong T, Pham TT, Le Nguyen D. Biochemistry. 2000;39:5722–5730. doi: 10.1021/bi9929756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Trabi M, Craik DJ. Plant Cell. 2004;16:2204–2216. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.021790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Trabi M, Svangard E, Herrmann A, Goransson U, Claeson P, Craik DJ, Bohlin L. J Nat Prod. 2004;67:806–810. doi: 10.1021/np034068e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gran L. Lloydia. 1973;36:207–208. [Google Scholar]

- 25.a) Hashempour H, Koehbach J, Daly NL, Ghassempour A, Gruber CW. Amino Acids. 2013;44:581–595. doi: 10.1007/s00726-012-1376-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Koehbach J, Attah AF, Berger A, Hellinger R, Kutchan TM, Carpenter EJ, Rolf M, Sonibare MA, Moody JO, Wong GK, Dessein S, Greger H, Gruber CW. Biopolymers. 2013;100:438–452. doi: 10.1002/bip.22328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farhadpour M, Hashempour H, Talebpour Z, ABN, Shushtarian MS, Gruber CW, Ghassempour A. Anal Biochem. 2016;497:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Velasquez JE, van der Donk WA. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2011;15:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J, Hua Z, Huang Z, Chen Q, Long Q, Craik DJ, Baker AJ, Shu W, Liao B. Planta. 2015;241:929–940. doi: 10.1007/s00425-014-2229-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hellinger R, Koehbach J, Soltis DE, Carpenter EJ, Wong GK, Gruber CW. J Proteome Res. 2015;14:4851–4862. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porto WF, Miranda VJ, Pinto MF, Dohms SM, Franco OL. Biopolymers. 2016;106:109–118. doi: 10.1002/bip.22771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Serra A, Hemu X, Nguyen GK, Nguyen NT, Sze SK, Tam JP. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23005. doi: 10.1038/srep23005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mulvenna JP, Wang C, Craik DJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D192–194. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Puttamadappa SS, Jagadish K, Shekhtman A, Camarero JA. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49:7030–7034. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colgrave ML, Craik DJ. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5965–5975. doi: 10.1021/bi049711q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weidmann J, Craik DJ. J Exp Bot. 2016;67:4801–4812. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang CK, Kaas Q, Chiche L, Craik DJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D206–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ravipati AS, Henriques ST, Poth AG, Kaas Q, Wang CK, Colgrave ML, Craik DJ. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10:2491–2500. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.a) Heitz A, Hernandez JF, Gagnon J, Hong TT, Pham TT, Nguyen TM, Le-Nguyen D, Chiche L. Biochemistry. 2001;40:7973–7983. doi: 10.1021/bi0106639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Mylne JS, Chan LY, Chanson AH, Daly NL, Schaefer H, Bailey TL, Nguyencong P, Cascales L, Craik DJ. Plant Cell. 2012;24:2765–2778. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.099085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chiche L, Heitz A, Gelly JC, Gracy J, Chau PT, Ha PT, Hernandez JF, Le-Nguyen D. Curr Protein Pep Sci. 2004;5:341–349. doi: 10.2174/1389203043379477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Craik DJ, Malik U. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2013;17:546–554. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jennings C, West J, Waine C, Craik D, Anderson M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10614–10619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191366898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arnison PG, Bibb MJ, Bierbaum G, Bowers AA, Bugni TS, Bulaj G, Camarero JA, Campopiano DJ, Challis GL, Clardy J, Cotter PD, Craik DJ, Dawson M, Dittmann E, Donadio S, Dorrestein PC, Entian KD, Fischbach MA, Garavelli JS, Goransson U, Gruber CW, Haft DH, Hemscheidt TK, Hertweck C, Hill C, Horswill AR, Jaspars M, Kelly WL, Klinman JP, Kuipers OP, Link AJ, Liu W, Marahiel MA, Mitchell DA, Moll GN, Moore BS, Muller R, Nair SK, Nes IF, Norris GE, Olivera BM, Onaka H, Patchett ML, Piel J, Reaney MJ, Rebuffat S, Ross RP, Sahl HG, Schmidt EW, Selsted ME, Severinov K, Shen B, Sivonen K, Smith L, Stein T, Sussmuth RD, Tagg JR, Tang GL, Truman AW, Vederas JC, Walsh CT, Walton JD, Wenzel SC, Willey JM, van der Donk WA. Nat Prod Rep. 2013;30:108–160. doi: 10.1039/c2np20085f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.a) Dutton JL, Renda RF, Waine C, Clark RJ, Daly NL, Jennings CV, Anderson MA, Craik DJ. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:46858–46867. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407421200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Simonsen SM, Sando L, Ireland DC, Colgrave ML, Bharathi R, Goransson U, Craik DJ. Plant Cell. 2005;17:3176–3189. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.034678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.a) Burman R, Gruber CW, Rizzardi K, Herrmann A, Craik DJ, Gupta MP, Goransson U. Phytochemistry. 2010;71:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Gruber CW. Biopolymers. 2010;94:565–572. doi: 10.1002/bip.21414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zhang J, Liao B, Craik DJ, Li JT, Hu M, Shu WS. Gene. 2009;431:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.a) Poth AG, Mylne JS, Grassl J, Lyons RE, Millar AH, Colgrave ML, Craik DJ. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:27033–27046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.370841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Nguyen GK, Zhang S, Nguyen NT, Nguyen PQ, Chiu MS, Hardjojo A, Tam JP. J Biol Chem. 2011 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.229922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.a) Saska I, Gillon AD, Hatsugai N, Dietzgen RG, Hara-Nishimura I, Anderson MA, Craik DJ. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29721–29728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705185200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Gillon AD, Saska I, Jennings CV, Guarino RF, Craik DJ, Anderson MA. Plant J. 2008;53:505–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harris KS, Durek T, Kaas Q, Poth AG, Gilding EK, Conlan BF, Saska I, Daly NL, van der Weerden NL, Craik DJ, Anderson MA. Nat Commun. 2015;6:10199. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nguyen GK, Wang S, Qiu Y, Hemu X, Lian Y, Tam JP. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:732–738. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marglin A, Merrifield RB. Annu Rev Biochem. 1970;39:841–866. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.39.070170.004205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dawson PE, Muir TW, Clark-Lewis I, Kent SBH. Science. 1994;266:776–779. doi: 10.1126/science.7973629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.a) Camarero JA, Muir TW. Chem Comm. 1997;1997:202–219. [Google Scholar]; b) Camarero JA, Pavel J, Muir TW. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:347–349. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980216)37:3<347::AID-ANIE347>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aboye T, Kuang Y, Neamati N, Camarero JA. Chembiochem. 2015;16:827–833. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thongyoo P, Roque-Rosell N, Leatherbarrow RJ, Tate EW. Org Biomol Chem. 2008;6:1462–1470. doi: 10.1039/b801667d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jia X, Kwon S, Wang CI, Huang YH, Chan LY, Tan CC, Rosengren KJ, Mulvenna JP, Schroeder CI, Craik DJ. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:6627–6638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.539262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.a) Kimura RH, Tran AT, Camarero JA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:973–976. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Austin J, Wang W, Puttamadappa S, Shekhtman A, Camarero JA. Chembiochem. 2009;10:2663–2670. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.a) Gould A, Li Y, Majumder S, Garcia AE, Carlsson P, Shekhtman A, Camarero JA. Mol Biosyst. 2012;8:1359–1365. doi: 10.1039/c2mb05451e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Conibear AC, Wang CK, Bi T, Rosengren KJ, Camarero JA, Craik DJ. J Phys Chem B. 2014 doi: 10.1021/jp507754c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.a) Jagadish K, Borra R, Lacey V, Majumder S, Shekhtman A, Wang L, Camarero JA. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52:3126–3131. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jagadish K, Gould A, Borra R, Majumder S, Mushtaq Z, Shekhtman A, Camarero JA. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54:8390–8394. doi: 10.1002/anie.201501186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jagadish K, Camarero JA. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1495:41–55. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6451-2_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Puttamadappa SS, Jagadish K, Shekhtman A, Camarero JA. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50:6948–6949. [Google Scholar]

- 60.a) Li Y, Aboye T, Breindel L, Shekhtman A, Camarero JA. Biopolymers. 2016;106:818–824. doi: 10.1002/bip.22875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Li Y, Gould A, Aboye T, Bi T, Breindel L, Shekhtman A, Camarero JA. J Med Chem. 2017;60:1916–1927. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.a) Jennings CV, Rosengren KJ, Daly NL, Plan M, Stevens J, Scanlon MJ, Waine C, Norman DG, Anderson MA, Craik DJ. Biochemistry. 2005;44:851–860. doi: 10.1021/bi047837h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Pinto MF, Fensterseifer IC, Migliolo L, Sousa DA, de Capdville G, Arboleda-Valencia JW, Colgrave ML, Craik DJ, Magalhaes BS, Dias SC, Franco OL. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:134–147. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.294009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.a) Colgrave ML, Kotze AC, Huang YH, O’Grady J, Simonsen SM, Craik DJ. Biochemistry. 2008;47:5581–5589. doi: 10.1021/bi800223y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Colgrave ML, Kotze AC, Ireland DC, Wang CK, Craik DJ. Chembiochem. 2008;9:1939–1945. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Malagon D, Botterill B, Gray DJ, Lovas E, Duke M, Gray C, Kopp SR, Knott LM, McManus DP, Daly NL, Mulvenna J, Craik DJ, Jones MK. Biopolymers. 2013;100:461–470. doi: 10.1002/bip.22229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Plan MR, Saska I, Cagauan AG, Craik DJ. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:5237–5241. doi: 10.1021/jf800302f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barbeta BL, Marshall AT, Gillon AD, Craik DJ, Anderson MA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:1221–1225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710338104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.a) Henriques ST, Huang YH, Castanho MA, Bagatolli LA, Sonza S, Tachedjian G, Daly NL, Craik DJ. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:33629–33643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.372011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Troeira Henriques S, Huang YH, Chaousis S, Wang CK, Craik DJ. Chembiochem. 2014;15:1956–1965. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.a) Huang YH, Colgrave ML, Daly NL, Keleshian A, Martinac B, Craik DJ. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:20699–20707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.003384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Henriques ST, Huang YH, Rosengren KJ, Franquelim HG, Carvalho FA, Johnson A, Sonza S, Tachedjian G, Castanho MA, Daly NL, Craik DJ. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:24231–24241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.253393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tam JP, Lu YA, Yang JL, Chiu KW. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8913–8918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.8913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.a) Nguyen GK, Zhang S, Wang W, Wong CT, Nguyen NT, Tam JP. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:44833–44844. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.290296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wong CT, Taichi M, Nishio H, Nishiuchi Y, Tam JP. Biochemistry. 2011;50:7275–7283. doi: 10.1021/bi2007004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pranting M, Loov C, Burman R, Goransson U, Andersson DI. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:1964–1971. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fensterseifer IC, Silva ON, Malik U, Ravipati AS, Novaes NR, Miranda PR, Rodrigues EA, Moreno SE, Craik DJ, Franco OL. Peptides. 2015;63:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.a) Gustafson KR, McKee TC, Bokesch HR. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2004;5:331–340. doi: 10.2174/1389203043379468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Daly NL, Gustafson KR, Craik DJ. FEBS Lett. 2004;574:69–72. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Chen B, Colgrave ML, Daly NL, Rosengren KJ, Gustafson KR, Craik DJ. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22395–22405. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501737200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Wang CK, Colgrave ML, Gustafson KR, Ireland DC, Goransson U, Craik DJ. J Nat Prod. 2008;71:47–52. doi: 10.1021/np070393g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gustafson KR, Walton LK, Sowder RC, Jr, Johnson DG, Pannell LK, Cardellina JH, Jr, Boyd MR. J Nat Prod. 2000;63:176–178. doi: 10.1021/np990432r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ireland DC, Wang CK, Wilson JA, Gustafson KR, Craik DJ. Biopolymers. 2008;90:51–60. doi: 10.1002/bip.20886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.a) Lindholm P, Göransson U, Johansson S, Claeson P, Gullbo J, Larsson R, Bohlin L, Backlund A. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:365–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Svangard E, Goransson U, Hocaoglu Z, Gullbo J, Larsson R, Claeson P, Bohlin L. J Nat Prod. 2004;67:144–147. doi: 10.1021/np030101l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Herrmann A, Burman R, Mylne JS, Karlsson G, Gullbo J, Craik DJ, Clark RJ, Goransson U. Phytochemistry. 2008;69:939–952. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Esmaeili MA, Abagheri-Mahabadi N, Hashempour H, Farhadpour M, Gruber CW, Ghassempour A. Fitoterapia. 2016;109:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2015.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hu E, Wang D, Chen J, Tao X. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:4059–4065. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pinto MF, Silva ON, Viana JC, Porto WF, Migliolo L, BdCN, Gomes N, Jr, Fensterseifer IC, Colgrave ML, Craik DJ, Dias SC, Franco OL. J Nat Prod. 2016;79:2767–2773. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Koehbach J, O’Brien M, Muttenthaler M, Miazzo M, Akcan M, Elliott AG, Daly NL, Harvey PJ, Arrowsmith S, Gunasekera S, Smith TJ, Wray S, Goransson U, Dawson PE, Craik DJ, Freissmuth M, Gruber CW. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:21183–21188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311183110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.a) Gunasekera S, Foley FM, Clark RJ, Sando L, Fabri LJ, Craik DJ, Daly NL. J Med Chem. 2008;51:7697–7704. doi: 10.1021/jm800704e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Thongyoo P, Bonomelli C, Leatherbarrow RJ, Tate EW. J Med Chem. 2009;52:6197–6200. doi: 10.1021/jm901233u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Eliasen R, Daly NL, Wulff BS, Andresen TL, Conde-Frieboes KW, Craik DJ. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:40493–40501. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.395442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Aboye TL, Ha H, Majumder S, Christ F, Debyser Z, Shekhtman A, Neamati N, Camarero JA. J Med Chem. 2012;55:10729–10734. doi: 10.1021/jm301468k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Balkwill F. Semin Cancer Biol. 2004;14:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Culp E, Wright GD. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2017;70:366–377. doi: 10.1038/ja.2016.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gialeli C, Theocharis AD, Karamanos NK. FEBS J. 2011;278:16–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sommerhoff CP, Avrutina O, Schmoldt HU, Gabrijelcic-Geiger D, Diederichsen U, Kolmar H. J Mol Biol. 2010;395:167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Thell K, Hellinger R, Schabbauer G, Gruber CW. Drug Discov Today. 2014;19:645–653. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang CK, Gruber CW, Cemazar M, Siatskas C, Tagore P, Payne N, Sun G, Wang S, Bernard CC, Craik DJ. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:156–163. doi: 10.1021/cb400548s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.D’Souza C, Henriques ST, Wang CK, Cheneval O, Chan LY, Bokil NJ, Sweet MJ, Craik DJ. Biochemistry. 2016;55:396–405. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kritzer JA, Hamamichi S, McCaffery JM, Santagata S, Naumann TA, Caldwell KA, Caldwell GA, Lindquist S. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:655–663. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang CK, Stalmans S, De Spiegeleer B, Craik DJ. J Pept Sci. 2016;22:305–310. doi: 10.1002/psc.2862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Camarero JA, Kimura RH, Woo YH, Shekhtman A, Cantor J. Chembiochem. 2007;8:1363–1366. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Moore SJ, Hayden Gephart MG, Bergen JM, Su YS, Rayburn H, Scott MP, Cochran JR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:14598–14603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311333110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Willmann JK, Kimura RH, Deshpande N, Lutz AM, Cochran JR, Gambhir SS. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:433–440. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.068007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.a) Jiang L, Tu Y, Kimura RH, Habte F, Chen H, Cheng K, Shi H, Gambhir SS, Cheng Z. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:939–944. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.155176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jiang L, Kimura RH, Ma X, Tu Y, Miao Z, Shen B, Chin FT, Shi H, Gambhir SS, Cheng Z. Mol Pharm. 2014;11:3885–3892. doi: 10.1021/mp500018s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.a) Zhu X, Li J, Hong Y, Kimura RH, Ma X, Liu H, Qin C, Hu X, Hayes TR, Benny P, Gambhir SS, Cheng Z. Mol Pharm. 2014;11:1208–1217. doi: 10.1021/mp400683q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jiang L, Miao Z, Kimura RH, Liu H, Cochran JR, Culter CS, Bao A, Li P, Cheng Z. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:613–622. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1684-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Teicher BA, Fricker SP. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2927–2931. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kuil J, Buckle T, van Leeuwen FW. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:5239–5261. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35085h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gao Y, Cui T, Lam Y. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Getz JA, Cheneval O, Craik DJ, Daugherty PS. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:1147–1154. doi: 10.1021/cb4000585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Thell K, Hellinger R, Sahin E, Michenthaler P, Gold-Binder M, Haider T, Kuttke M, Liutkeviciute Z, Goransson U, Grundemann C, Schabbauer G, Gruber CW. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:3960–3965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1519960113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Maass F, Wustehube-Lausch J, Dickgiesser S, Valldorf B, Reinwarth M, Schmoldt HU, Daneschdar M, Avrutina O, Sahin U, Kolmar H. J Pept Sci. 2015;21:651–660. doi: 10.1002/psc.2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Quimbar P, Malik U, Sommerhoff CP, Kaas Q, Chan LY, Huang YH, Grundhuber M, Dunse K, Craik DJ, Anderson MA, Daly NL. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:13885–13896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.460030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chan LY, Gunasekera S, Henriques ST, Worth NF, Le SJ, Clark RJ, Campbell JH, Craik DJ, Daly NL. Blood. 2011;118:6709–6717. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-359141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Huang YH, Henriques ST, Wang CK, Thorstholm L, Daly NL, Kaas Q, Craik DJ. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12974. doi: 10.1038/srep12974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Aboye T, Meeks CJ, Majumder S, Shekhtman A, Rodgers K, Camarero JA. Molecules. 2016;21:152. doi: 10.3390/molecules21020152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Swedberg JE, Mahatmanto T, Abdul Ghani H, de Veer SJ, Schroeder CI, Harris JM, Craik DJ. J Med Chem. 2016;59:7287–7292. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chan LY, Craik DJ, Daly NL. Biosci Rep. 2015:35. doi: 10.1042/BSR20150210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chan LY, Craik DJ, Daly NL. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35347. doi: 10.1038/srep35347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]