Abstract

Adolescent and young adult abuse of short-acting MOP-r agonists such as oxycodone is a pressing public health issue. Few preclinical studies have examined how adolescent exposure to oxycodone impacts its effects in the transition to adulthood.

Objective

To determine in mice how chronic adolescent oxycodone self-administration (SA) affects subsequent oxycodone-induced conditioned place preference (CPP), locomotor activity, and anti-nociception once mice reach early adulthood.

Methods

Adolescent C57BL/6J male mice (4 weeks old, n = 6–11) and adult mice (10 weeks old, n = 6–10) were surgically implanted with indwelling jugular catheters. Mice then acquired oxycodone self-administration (14 consecutive 2-hr daily sessions; 0.25 mg/kg/infusion) followed by a 14-day drug-free (withdrawal) period in home cage. After the 14-day drug-free period, mice underwent a 10-day oxycodone CPP procedure (0, 1, 3, 10 mg/kg i.p.) or were tested for acute oxycodone-induced anti-nociception in the hot plate assay (3.35, 5, 7.5 mg/kg i.p.).

Results

Mice that self-administered oxycodone during adolescence exhibited greater oxycodone-induced CPP (at the 3 mg/kg dose) than their yoked saline controls and mice that self-administered oxycodone during adulthood. Oxycodone dose-dependently increased locomotor activity, but sensitization developed only to the 3 mg/kg in the mice that underwent oxycodone self-administration as adolescents. Mice that self-administered oxycodone as adolescents decreased in the anti-nociceptive effects of oxycodone in one dose (5 mg/kg), whereas animals that self-administered oxycodone as adults did not show this effect.

Conclusion

Chronic adolescent oxycodone self-administration led to increased oxycodone-induced CPP (primarily 1 and 3 mg/kg, i.p.) and reduced antinociceptive effect of oxycodone (5 mg/kg, i.p.) in adulthood.

Keywords: Oxycodone, Adolescent, Self administration, Conditioned place preference, Hotplate test

1. Introduction

Non-medical use of prescription opioids such as the mu opioid receptor (MOP-r) agonist oxycodone, especially among adolescents and young adults, has increased in recent years and is a major public health concern in the United States (Johnston et al., 2016). Adolescence is a period of heightened sensation seeking, which can include disinhibition and risk-taking behavior (Spear, 2000a, 2000b), potentially due to an imbalance between immaturity of the prefrontal cortex and lack of self-control resulting from developmental changes in the mesocoticolimbic systems (e.g., (Chambers et al., 2003; Yurgelun-Todd, 2007; Crews and Boettiger, 2009). The adolescent brain undergoes programmed reorganizations, remodeling, and maturational refinements corresponding to a variety of molecular changes in different cell types. For example, studies in juvenile rodents have shown that dopamine receptor density increases in the striatum during early adolescence and decreases during later adolescence and early adulthood (Teicher et al., 1991, 2003; Andersen et al., 1997; Teicher et al., 2003); dopaminergic function is known to be involved in the rewarding effects of major drugs of abuse. Prefrontal cortex gluta-matergic projections innervating the nucleus accumbens (Brenhouse et al., 2008) and amygdala (Cunningham et al., 2002) increase during adolescence. Since adolescent brains are in a state of developmental flux, they may be more vulnerable to various insults, including drugs of abuse. Adolescent exposure to drugs of abuse, including prescription opioids, may increase the likelihood of neurobiological changes, predisposing the adolescents to be more susceptible to the effects of these drugs, leading to behavioral alterations upon subsequent or continued exposure during the transition to early adulthood.

We have recently developed an animal model of chronic oxycodone self-administration to examine the behavioral and underlying neurobiological consequences of oxycodone exposure in adolescent mice. Our earlier studies found that adolescent mice exhibited differential oxycodone self-administration behavior compared to adult mice (Zhang et al., 2009; Mayer-Blackwell et al., 2014) and differential behavioral response to oxycodone in adolescent versus adult mice (Niikura et al., 2013), as well as differential adaptations in mRNA expression for several genes in the mouse brain (Zhang et al., 2009; Mayer-Blackwell et al., 2014).

We hypothesized that exposure to oxycodone during adolescence would result in characteristic adaptations to the effects of oxycodone in reward- and non-reward related endpoints, once these animals reach adulthood. To test this hypothesis, the current study examined whether chronic adolescent oxycodone self-administration affects oxycodone-induced conditioned place preference (CPP) and the anti-nociceptive property of oxycodone during adulthood in a mouse model. Specifically, mice that had self-administered oxycodone during adolescence underwent either an oxycodone-induced CPP procedure or were tested for thermal antinociception following 14 days withdrawal from 14 consecutive daily oxycodone self-administration sessions. CPP and anti-nociception testing thus occurred after these mice had entered young adulthood. These animals were compared to those undergoing similar procedures, but which self-administered oxycodone in young adulthood.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

Male adolescent and adult (4 or 10 week old on arrival) C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were housed in groups of five with free access to food and water in a light-(12:12 h light/dark cycle, lights on at 7:00 p.m.) and temperature-(25 °C) controlled room. Animal care and experimental procedures were conducted according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources Commission on Life Sciences 1996). The experimental protocols used were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The Rockefeller University. The time line of self-administration and later CPP or hot plate test studies and the ages of mice are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Age and experimental procedure.

| On arrival | Surgery | 14-day SA | Withdrawal | CPP or Hotplate test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent postnatal day | 28 | 35 | 42–56 | 57–70 | 71–80 | 71 |

| Adult postnatal day | 70 | 77 | 78–91 | 92–105 | 106–115 | 106 |

2.2. Self-administration of oxycodone

2.2.1. Catheter implantation

Following acclimation for 7 days, the mice were anesthetized with a combination of xylazine (8.0 mg/kg i.p.) and ketamine (80 mg/kg i.p.). After shaving and application of a 70% alcohol and iodine preparatory solution, incisions were made in the mid-scapular region and anteromedial to the foreleg. A catheter approximately 6 cm in length (ID: 0.31 mm, OD: 0.64 mm; Helix Medical, Inc. CA) was passed subcutaneously from the dorsal to the ventral incision. After exposure of the right jugular vein, a 22-gauge needle was inserted, to guide the catheter into the jugular vein. Once the catheter was inside the vein, the needle was removed and the catheter was inserted to the level of a silicone ball marker, 1.1 cm from the end. The catheter was tied to the vein with surgical silk. Physiological saline then was flushed through the catheter to avoid clotting, and the catheter then capped with a stopper. Antibiotic ointment was applied to the catheter exit incisions on the animal’s back and foreleg. Mice were group housed after the surgery and were allowed 7 days of recovery before being placed in operant test chambers for the self-administration procedure (Zhang et al., 2009; Mayer-Blackwell et al., 2014).

2.2.2. Intravenous self-administration chamber

The self-administration chamber (ENV-307W: 21.6 cm × 17.8 cm × 12.7 cm; Med Associates, St. Albans, VT) was located inside a sound attenuating chamber (Med Associates). The front, back and top were constructed of 5.6 mm polycarbonate. Each chamber contained a wall with two small holes (0.9 cm diameter, 4.2 cm apart, 1.5 cm from the floor of the chamber). One hole was defined as active, the other was inactive. When the photocell in the active hole was triggered by a nose-poke, the infusion pump (Med Associates) delivered an infusion of 20 μl/3 s from a 5 ml syringe connected by a swivel via Tygon tubing. The infusion pump and syringe were located outside the chamber. During infusion, a cue light above the active hole was illuminated. Each injection was followed by a 20-sec “time-out” period during which poking responses were recorded but had no programmed consequences. All responses at the inactive hole were also recorded. Mice were tested during the dark phase of the diurnal cycle (all experiments were performed between 8:00 a.m. and 2:00 p.m.).

2.2.3. Oxycodone self-administration

A 2-hr self-administration session was conducted once a day. Each day, mice were weighed and the catheter flushed with heparinized saline (0.01 ml of 30 IU/ml solution) to maintain patency. During each of the 14 self-administration sessions, mice in the oxycodone (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) groups received an infusion of oxycodone (0.25 mg/kg/infusion) under an FR1 schedule following each active hole nose poke. During all sessions, mice in the yoked control groups received a saline infusion (20 μl/inf) when the oxycodone mouse self-administered oxycodone.

At the end of the self-administration experiment, only data from mice that passed a catheter patency test [defined as loss of muscle tone within a few seconds after i.v. administration of 30 μl of ketamine (5 mg/ml; Fort Dodge, IA)] were included in the analysis of self-administration data. Of a total 346 mice that started the study, 217 mice finished the 14-day self-administration study and passed the catheter patency test. Of these 217 mice, 130 mice finished the conditioned place preference study, and 84 mice finished the anti-nociception study, 3 mice were not included in either study because of health issues.

2.3. Oxycodone-induced conditioned place preference

2.3.1. Mouse place preference chambers

The mouse place preference chambers have three distinct compartments that can be separated by removable doors (ENV-3013; Med Associate, VT). Movement within each compartment was tracked by individual infrared photobeams on a photobeam strip (six beams in the white and black compartments and two beams in the smaller central gray compartment). The center compartment had a solid neutral gray floor and gray walls. The black and white compartments (16.8 × 12.7 × 12.7 cm) had a stainless steel rod and mesh floors, respectively.

2.3.2. Locomotor activity and CPP determinations

Four groups of mice (n = 6–10) in each age group were studied, one group at each dose: 0 (vehicle), 1, 3 and 10 mg/kg of oxycodone. Experiments were performed in a dimly-lit, sound attenuated chamber described above. The study used an unbiased, counterbalanced design in which mice were randomly assigned to either the oxycodone or saline compartment on the first day. Half the animals had white and half had black as the oxycodone-paired side. During the pre-conditioning session, each animal was placed in the center compartment with free access to all compartments. The time spent in each compartment and locomotor activity within the compartments were recorded for 30 min. Locomotor activity was assessed as the number of “crossovers” defined as breaking the photobeams at either end of the conditioning compartment. During the conditioning sessions, mice were placed into and restricted to the appropriate compartment for 30 min following oxycodone or saline injection. Conditioning sessions occurred at the same time each day with animals injected with oxycodone and saline on alternate days, for a total of eight conditioning sessions (four with oxycodone and four with saline). The post-conditioning test session was performed on the day after the last conditioning session, and was identical to the pre-conditioning session: each mouse had free access to all compartments. The schedule of sessions is shown in Table 2. Oxycodone CPP was determined by the difference between the pre- and post-conditioning sessions for the amount of time spent in the drug-paired compartment and compared to vehicle controls.

Table 2.

10-Day CPP procedure.

| DAY1 | DAY2 | DAY3 | DAY4 | DAY5 | DAY6 | DAY7 | DAY8 | DAY9 | DAY10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-CS | CS | CS | CS | CS | CS | CS | CS | CS | Post-CS- |

CS: Conditioning Session.

2.4. Hotplate anti-nociception

Six separate groups of mice (n = 6–11) that had self-administered oxycodone in adolescence or adulthood (and their saline yoked-control groups) were measured for oxycodone-induced analgesia following 14-day withdrawal. The apparatus consisted of a clear, plexiglas cylinder placed on a hotplate (IITC Inc., Woodland Hills; CA). Mice were allowed to walk on the hot-plate (55 °C) for up to 45 s (maximum allowed latency; to avoid tissue damage). Basal measurements (2 h before injection) and measurements at 10, 30, 60 min post-injection of one of the three doses (3.35, 5, 7.5 mg/kg, i.p.) of oxycodone were taken. Latency to jump, hind paw lick or hind paw flick was recorded, up to the maximum 45 s (if the animal did not emit such a response). Each mouse received only one oxycodone injection on the hotplate testing day. Mice were divided into different groups, based on the injection doses (3.35, 5, and 7.5 mg/kg, i.p.), prior self-administration exposure (oxycodone vs yoked saline), and age of this self-administration exposure (adolescent vs adult).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Differences in self-administration measured as the total number of active hole nose pokes for each SA session across the 14 sessions were assessed by a three-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), Age (Adolescent, Adult) × Condition (Oxycodone SA, Yoked Saline Control) × Session (1–14; repeated measures). Differences in locomotor activity during place conditioning sessions were analyzed with a 4-way ANOVA, Age (Adolescent, Adult) × Condition (Oxy-codone SA, Yoked Saline Control) × Dose (0, 1, 3, 10 mg/kg) × Session (1–4; repeated measures). Oxycodone-induced CPP was analyzed by a three-way ANOVA, Age (Adolescent, Adult) × Condition (Oxycodone SA, Yoked Saline Control) × Dose (0, 1, 3, 10 mg/kg). Baseline latency for the hotplate test was analyzed with 2-way ANOVA, Age (Adolescent, Adult) × Condition (Oxycodone SA, Yoked Saline Control). Antinociceptive effects of oxycodone were analyzed as percent maximum possible effect (% MPE), with the following standard transformation: %MPE = [(test latency−baseline latency)/(maximum cutoff latency−baseline latency)] × 100. Negative %MPE values were converted to 0%MPE for analysis. Area under the curve (AUC) was calculated from %MPE time-effect curve for the available time points (i.e., 10, 30, and 60 min post-oxycodone). Antinociception data were analyzed initially with a three-way ANOVA, Age (Adolescent, Adult) × Pretreatment Condition (Oxycodone SA, Yoked Saline Control) × AUC.

3. Results

3.1. Adolescent and adult C57BL/6 mice self-administration behavior

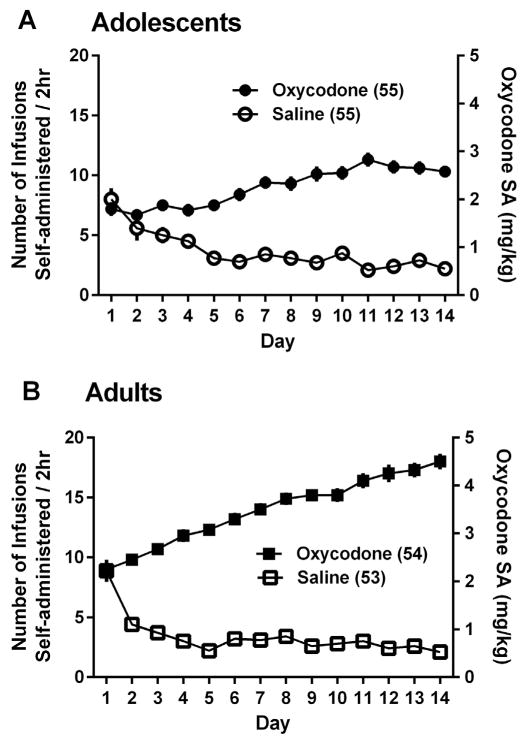

The behavior of all the adolescent and adult mice that completed the 14-day self-administration and passed the patency test is shown in Fig. 1. There were no differences in the self-administration behavior of mice which were assigned to the CPP or antinociception study (data not shown), and they were thus combined.

Fig. 1.

The total amount of self-administered oxycodone (Right Y axis) and number of infusion (left Y axis) across 14 consecutive sessions by adolescent mice (A) and adult mice (B).

A three-way ANOVA, for Age (Adolescent or Adult) × Drug Condition (oxycodone or saline) × Session (Days 1–14) showed a significant main effect of Age [F(1,213) = 47.89, p < 0.000001], and a significant main effect of Drug Condition [F(1,213) = 564.62, p < 0.000001] with a significant interaction of Age × Drug Condition [F(1,213) = 59.50, p < 0.000001]. Adolescents self-administered fewer oxycodone infusions than adults over the course of the 14 sessions (i.e., had lower total oxycodone intake). All mice in the above groups then underwent a 14-day drug-free period in home cage, followed by the experiments described below. At the end of this 14-days drug free-period, the original adolescent SA groups were therefore approximately postnatal 71 days old and had entered young adulthood. The comparison adult group had reached postnatal 106 day and therefore was still in young adulthood.

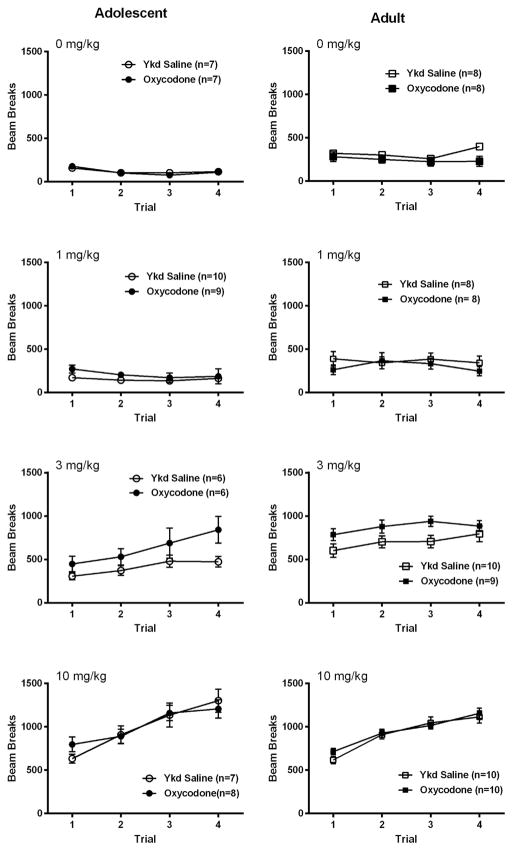

3.2. Oxycodone-induced locomotor activity during CPP training sessions

The mean (+SEM) locomotor activity across the four 30-min conditioning sessions following administration of oxycodone or saline by each age group, drug history and at each conditioning dose is shown in Fig. 2. A 4-way ANOVA, Age (Adult, Adolescent) × Drug Experience (Oxycodone SA, Yoked Saline) × Dose (0, 1, 3,10 mg/kg) × Session (1–4; repeated measures) was conducted. There was a significant main effect of Age [F(1,115) = 17.73, p < 0.0001], a significant main effect of Dose [F(3,115) = 12.13, P < 0.000001], and a significant main effect of Session [F(3,345) = 62.11, p < 0.000001]. There were four significant interaction effects involving Age Groups: Age × Dose [F(3,115) = 5.33, p < 0.002], Age × Session [F(3,345) = 3.73, p < 0.02], Age × Dose × Session [F(9,345) = 1.99, p < 0.05], and Age × Drug Experience × Dose × Session [F(9,345) = 2.26, p < 0.02].

Fig. 2.

The mean (±SEM) locomotor activity across the four 30-min conditioning sessions after administration of oxycodone or saline by each age group, drug history, and conditioning dose. In 3 mg/kg dose of Adolescent Oxycodone SA group, by the 4th session, their activity was significantly greater than that of the Yoked Saline control, p < 0.05.

We next examined locomotor activity at the 3 mg/kg dose since adolescent and adult mice differed in this dose group, as may be seen in Fig. 2, in a two-way ANOVA, Age Group × Drug Experience × Session with repeated measures on the last factor. Each of the main effects were significant: Age Group F(1,27) = 11.82, p < 0.002, Drug Experience F(1,27) = 6.15, p < 0.02, and Session F(3,81) = 17.96, p < 0.000001. Of interest, there was a significant Age Group × Drug Experience × Session interaction, F(3,81) = 3.05, p < 0.05. The adult SA groups showed greater activity than the adolescent SA groups, and subjects that had self-administered oxycodone showed greater activity than the Yoked Saline controls. Also, locomotor activity increased across sessions. A further difference between the two Age Groups is that in the Adolescent Oxycodone SA group, by the 4th session, activity was significantly greater than that of the Yoked Saline control, p < 0.05 (planned comparison), but this did not happen in the respective adult SA groups.

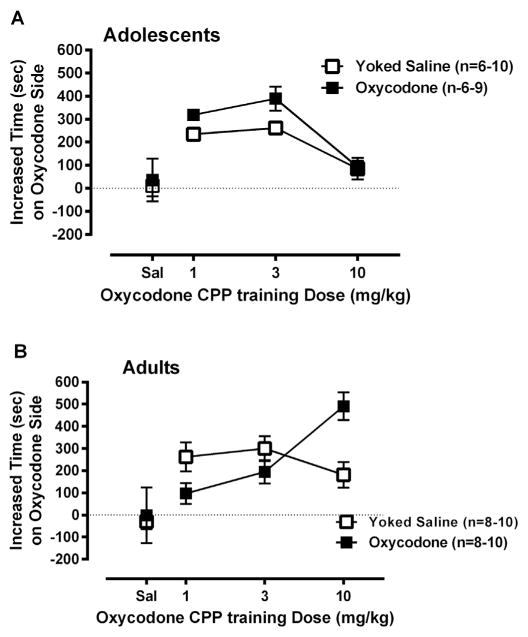

3.3. Oxycodone-induced conditioned place preference (CPP)

CPP, measured as increased time in the drug-paired chamber from pre-test to post-test, was examined first by a three-way ANOVA (Age × Drug Experience × Dose). There was a significant main effect of Dose [F(3,115) = 18.99, p < 0.000001]. There were two significant interactions involving Age Groups: an Age × Dose interaction [F(3, 115) = 7.67, p < 0.0002] and an Age × Drug Experience × Dose interaction [F(3,115) = 4.67, p < 0.005]. The mean (+SEM) time in the drug-paired side for each Drug Experience group at each Dose is shown in Fig. 3 (Adolescent in panel 3A; and Adult in panel 3B). As can be seen in Fig. 3A, mice which self-administered oxycodone as adolescents as well as the yoked adolescent controls showed greater CPP responses at 1 and 3 mg/kg oxycodone doses, but not at 10 mg/kg, compared to the vehicle control. By contrast, mice that had self administered oxycodone as adults showed a dose-dependent increase in oxycodone-induced CPP, that is, with greatest CPP scores at the 10 mg/kg dose. Adult yoked saline controls showed a place preference for oxycodone compared to vehicle control, but preference for oxycodone did not increase in a dose-dependent manner (see especially data for the 10 mg/kg oxycodone conditioning dose; Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

The mean (±SEM) difference in time spent on drug-paired side from pre- to post-conditioning session for adolescent and adult self-administration mice and yoked saline controls. The younger groups with or without oxycodone self-administration experience showed significant increases in oxycodone-induced CPP compared with vehicle controls (0 mg/kg). The mice that had self administered oxycodone as adolescents showed greater CPP at 1 and 3 mg/kg dose compared to adolescent yoked saline controls, p < 0.05 (B). The older groups with or without oxycodone self-administration experience also showed significant increases in oxycodone-induced CPP compared with vehicle controls. However, there were no significant difference in oxycodone-induced CPP between the two adult groups with or without prior oxycodone self administration, p = 0.97 (B).

Overall, there was a different pattern of oxycodone-induced CPP across the oxycodone conditioning doses, for mice that self-administered oxycodone during adolescence versus adulthood (Fig. 4B). A two-way ANOVA, for Age × Dose of the mice that had self-administered oxycodone showed a significant main effect of Dose [F(3,57) = 8.39, p < 0.0002] and also, a significant Age × Dose interaction [F(3,57) = 10.09, p < 0.00005]. Post hoc tests revealed that at the 1 mg/kg dose and 3 mg/kg dose, the mice that self-administered oxycodone as adolescents spent significantly more time in the drug-paired chamber than those self-administered as adults (p < 0.005 and p < 0.05, respectively; planned comparison). At the 10 mg/kg dose, the effect of age of oxycodone SA experience was reversed: the Adult Group spent significantly more time in the drug-paired chamber than did the Adolescent Group (p < 0.00001).

Fig. 4.

There is little difference in CPP between age groups that had never self-administered oxycodone (A), there is a different pattern of responses across the Doses by Age Group among the mice that had self-administered oxycodone during adolescence versus adulthood, p < 0.005, p < 0.05 and p < 0.00001 for 1, 3 and 10 mg/kg dose, respectively (B).

Based on the rationale of the overall study, we also compared oxycodone-induced CPP in mice that had self-administered oxycodone and served as yoked saline controls, within each of the age groups. In the adolescent groups, two-way ANOVA (Drug Experience × Dose) found that a significant main effect of Drug Experience [F(1,53) = 4.60, p < 0.05] in the adolescent self-administration groups. Thus, mice that had self administered oxycodone during adolescence spent more time in the oxycodone paired chamber than age-matched yoked saline controls in both 1 and 3 mg/kg groups, but this was not observed in the mice that had self-administered oxycodone as adults [F(1,63) = 0.001, p = 0.97].

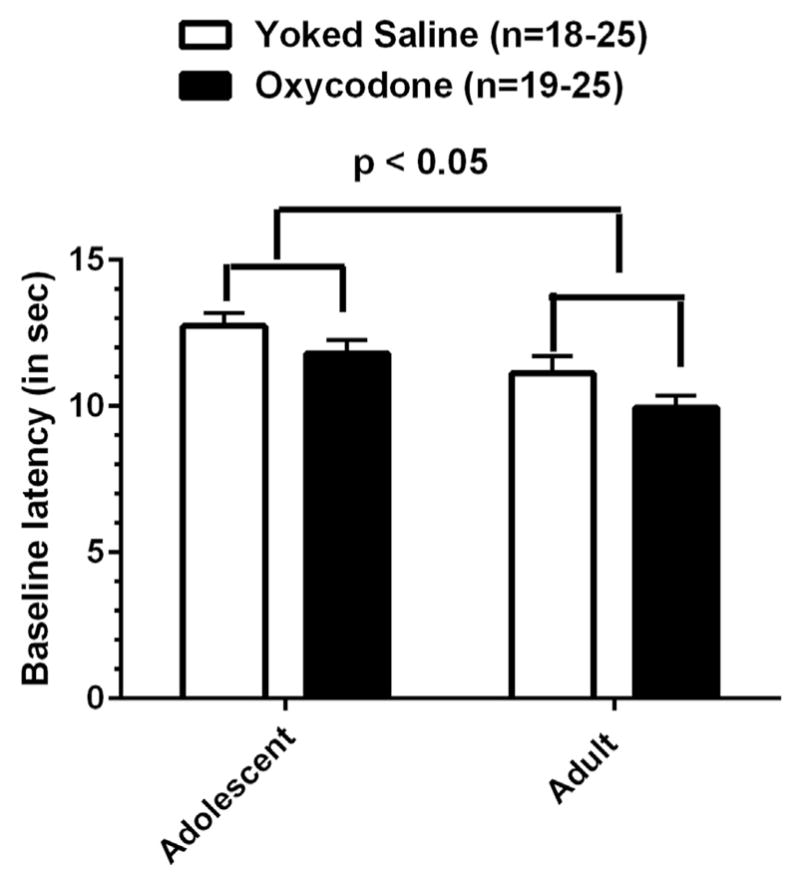

3.4. Oxycodone-induced anti-nociception

We first characterized the baseline latency, determined prior to oxycodone injection, in all sessions combined. A two-way ANOVA found a significant main effect of Age [F(1,83) = 12.84, p < 0.001]. A significant main effect of Condition [F(1,83) = 4.828, p < 0.05] was also found, with no significant interaction (Fig. 5). Thus the younger animals that had self-administered oxycodone and served as yoked saline controls in adolescence had higher baseline latencies than those that underwent the self-administration sessions in adulthood. Also, animals that underwent oxycodone self administration had significantly lower baseline latencies than animals in the yoked saline groups.

Fig. 5.

Baseline latency to the hotplate in both younger and older groups is shown. Younger groups showed significant higher baseline latency compared to the older group, p < 0.05. The oxycodone SA groups showed lower baseline latency compared to yoked saline controls, p < 0.005.

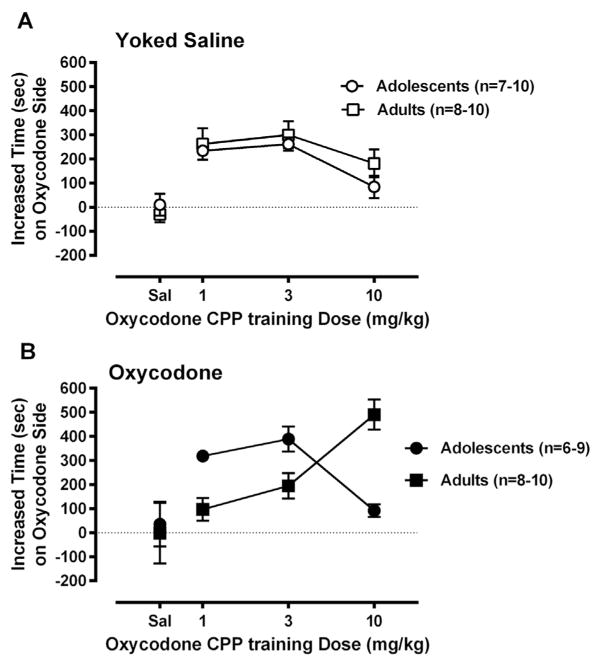

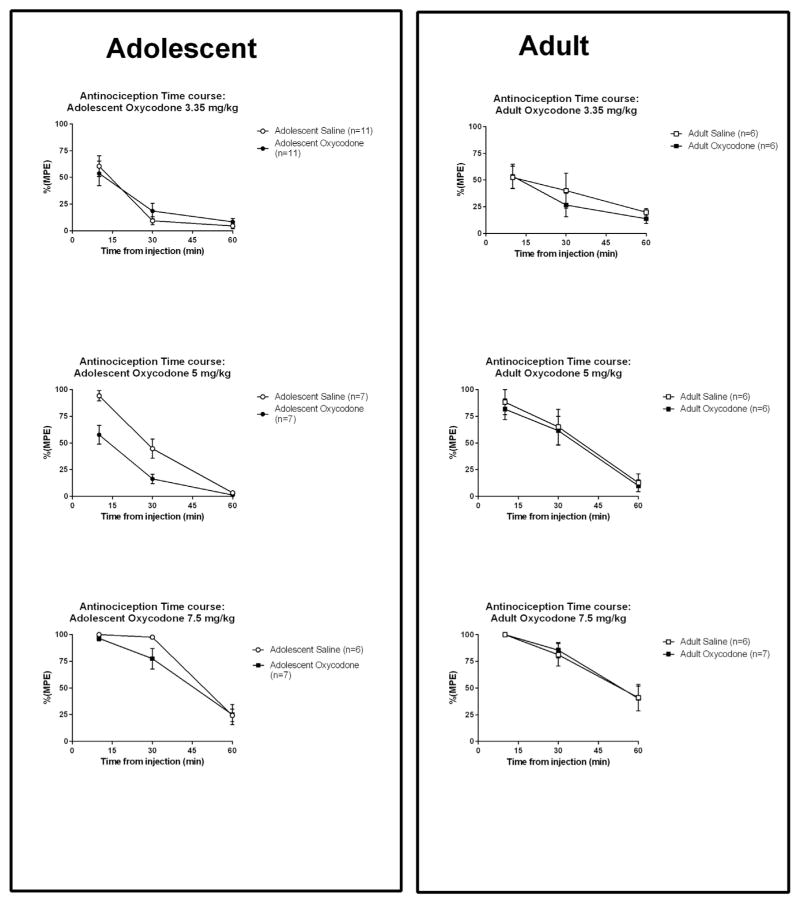

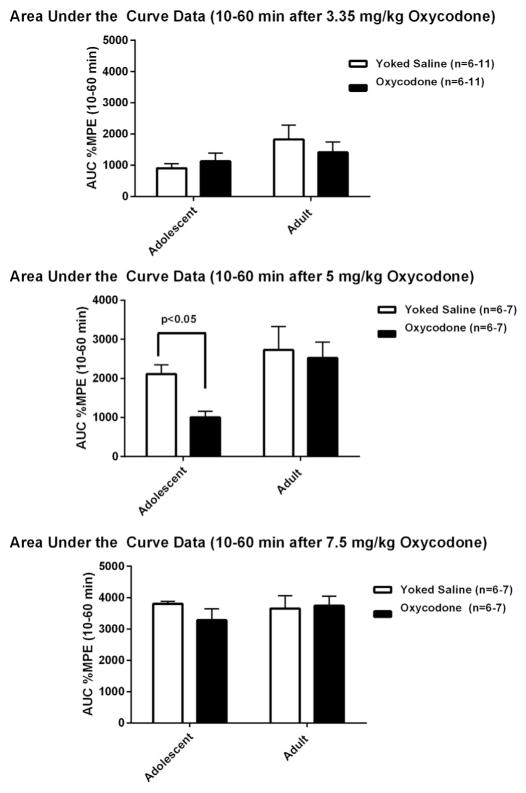

Oxycodone-induced anti-nociception (transformed as %MPE) was calculated and data is shown in Fig. 6. These data were then analyzed and presented as the mean + SEM of area under the curve (AUC) across 10, 30 and 60 min after oxycodone injection, when values were collected (time “0”, i.e., immediately after the injection, is not usually collected in such antinociception studies (Fig. 7). This shows data for mice that had self administered oxycodone, or served as yoked saline controls during adolescence or adulthood. A three–way ANOVA, Age × Drug Experience (Oxycodone or Yoked Saline) × Dose (3.35, 5, or 7.5 mg/kg) shows a significant main effect of Age [F(1,74) = 10.54, p < 0.002]. There was also a significant main effect of Dose [F(2,74) = 52.85, p < 0.00001]. There was neither a significant main effect of Drug Experience, nor were there interaction effects. A planned comparison showed that the mice that self-administered oxycodone in adolescence had a lower oxycodone induced antinociception at the 5 mg/kg dose, compared to the adolescent yoked saline group [F(1,74) = 10.33, p < 0.002]. Such an effect was not found in the mice that self-administered oxycodone as adults.

Fig. 6.

Time course of %MPE data presented from 10 to 60 min in mice that had self administered oxycodone or yoked saline controls in adolescence (left) and adult (right).

Fig. 7.

Oxycodone-induced antinociception, presented as the mean of area under the curve (AUC) of %MPE data across 10, 30 and 60 min after oxycodone injection, in mice that had self administered oxycodone or served as yoked saline controls in both age groups. A contrast of the age groups that had self administered oxycodone at the 5.0 mg/kg dose showed that the younger mice had a lower AUC than the older mice, p < 0.05. Mice that had self administered oxycodone as adolescents showed a significant decrease in oxycodone-induced antinociception after 5 mg/kg oxycodone injection compared to the same age yoked saline control. Such effect was not found in the older group.

4. Discussion

The current study examined the impact of 14-day adolescent oxycodone self administration on oxycodone-induced CPP, locomotor activity, and oxycodone-induced antinociceptive effects after a 14 day drug-free period, thus when these mice reached young adulthood. This was compared to a group that underwent the same protocol, but with the initial oxycodone self-administration sessions occurring in adulthood. As mentioned above, testing in the CPP and antinociception endpoints occurred 14 days after the end of the oxycodone/saline self-administration period (by which time, the adolescent group had reached young adulthood; postnatal day 71) (Adriani and Laviola, 2003), and after the period when classic MOP-r agonist withdrawal or tolerance effects are usually studied (Zhou et al., 2006; Kumar et al., 2008; Seip et al., 2012; Seip-Cammack et al., 2013). Overall, adolescent and adult oxycodone self-administration led to differential adaptations of oxycodone-induced CPP, locomotor activity, and antinociceptive effects, when measured in young adulthood.

Earlier studies in our and other laboratories have found oxycodone-induced CPP in both adult (Minami et al., 2009; Niikura et al., 2013) and adolescent mice (Niikura et al., 2013). Here, we found that mice with prior oxycodone self-administration during adolescence exhibited greater oxycodone-induced CPP (i.e., at the 1 and 3 mg/kg oxycodone conditioning dose) compared to vehicle. In addition, mice that had self administered oxycodone in adolescence showed greater CPP compared with yoked saline mice of the same age. This finding suggests adolescent oxycodone self-administration sensitized the rewarding effect of oxycodone, when studied in early adulthood. However, while mice exposed to the 1 and 3 mg/kg conditioning dose showed sensitization to oxycodone-induced CPP, those injected with a higher dose (10 mg/kg) did not. Overall, these findings are consistent with clinical findings showing that adolescents that had exposure to drugs of abuse have higher risk of development of addiction in adulthood (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2010).

In contrast, mice that had self administered oxycodone during adulthood showed different CPP behavioral profiles compared to the groups that had self-administered oxycodone as adolescents. Thus, 1 mg/kg oxycodone failed to induce CPP (i.e., no difference from vehicle), whereas the 3 and 10 mg/kg dose induced CPP compared to vehicle, with no significant difference in CPP compared to yoked saline controls of the same age in 1 and 3 mg/kg groups.

Oxycodone injections induced increases in locomotor activity during conditioning sessions for all the doses tested compared with saline controls, in both age groups. There was a significant difference in oxycodone-induced locomotor activity between mice with or without prior oxycodone self administration experience in the 3 mg/kg dose groups. By the fourth conditioning session for the 3 mg/kg oxycodone group, the adolescent oxycodone self administration mice had significantly greater activity than that of the yoked saline control. This may be interpreted as a greater sensitization effect of oxycodone self administration in the adolescent group than adult group.

Mice that had self administered oxycodone during adolescence showed decreases in oxycodone-induced antinociception in the hotplate test, following acute injection of 5 mg/kg of oxycodone (i.e., the intermediate dose studied here), compared to age-matched yoked-saline controls. This effect was not observed in the comparable groups that self-administered oxycodone as adults. This is especially interesting since the younger mice showed higher baseline latency than the older ones, and baseline latency is lower in mice that had self administered oxycodone than those served as yoked saline control. It is unclear if greater tolerance could not be observed due to “ceiling” effects at the largest oxycodone dose studied herein. One study found that adult mice developed tolerance to morphine challenge following 24 h withdrawal from 3-day subcutaneous morphine (30 mg/kg) pellet implantation (Bogulavsky et al., 2009). The different findings in the two studies may result from difference in experimental design, drugs used and conditions. Therefore it would be of value to expand the present studies with systematic comparisons of exposure to different MOP-r agonists, in adolescence vs adulthood.

These differential changes to oxycodone-induced CPP and antinociception may be potentially related to the different amount of oxycodone self administered during adolescence and adulthood, as the mean total intake over the 14 days of oxycodone self-administration was significantly greater in adults than adolescents. However, the changes observed are not simply quantitatively related to this differential intake. Rather, the overall pattern of sensitization of CPP differs for subjects that self-administered oxycodone in adolescence versus adulthood. Also, only a modest tolerance to the oxycodone-induced anti-nociception was observed in the adolescents (i.e., at one oxycodone dose). Therefore, animals which had self-administered oxycodone as adults displayed little evidence of tolerance under these conditions, even though they had greater oxycodone intake than the adolescent group. Of note, our CPP and antinociception measurements occurred after a 14-day drug free period, considerably longer than most studies of MOP-r agonist tolerance, to allow for the transition from adolescence to adulthood. We speculate that changes in synaptic plasticity in pathways that are involved in pain and reward may occur in the mice that had self administered oxycodone in adolescent more than in the adult mice (Zhang et al., 2014; 2015, Dong et al., 2007). We cannot exclude that the differential profile observed between adult and adolescent exposure to oxycodone herein are due in part to pharmacokinetic differences across these age periods. We are not aware of data on comparative oxycodone pharmacokinetics between adolescent and adult mice.

Age plays an important role in determining the behavioral and neurochemical outcomes (e.g., Badanich et al., 2006). For example, a study found that early and late adolescent rats developed conditioned place preference to 20 mg/kg of cocaine. But only early adolescents developed conditioned place preference to 5 mg/kg of cocaine. In addition, the basal dopamine levels on PND 35, which are also known to be affected by MOP-r ligands, are lower than those of young adults on PND 60 (Badanich et al., 2006). In the current study, it is important to note that oxycodone self administration by the adolescent mice started in the mid-late adolescence and withdrawal occurred in the late adolescence, and then oxycodone-induced CPP and anti-nociception were examined during early young adulthood.

Oxycodone acts primarily as a MOP-r agonist. Exposure to oxycodone (MOP-r agonist) causes changes in gene expression levels of MOP-r in reward-related brain regions. For example, MOP-r mRNA decreased on the first day of withdrawal and returned to basal levels over time, following 9–10 days heroin SA in rats in NAc (Theberge et al., 2012). In contrast, withdrawal from chronic intermittent escalating-dose morphine led to an increase in MOP-r mRNA levels in the NAc core and CPu (Zhou et al., 2006). We have found that chronic MOP-r agonist self-administration in mice results in differential adaptations in mRNA expression of specific targets in brain, when studied in 24 h withdrawal. It remains to be studied whether alterations in MOP-r mRNA or protein levels, as well as those of other targets, differ between adolescent and adult mice, especially after more prolonged drug-free periods and during the transition to adulthood, as studied herein.

Overall, these findings show that differential behavioral adaptations develop when animals chronically self-administered oxy-codone in adolescence versus adulthood, with respect to abuse-and non-abuse related endpoints. This is consistent with differential adaptations in the expression of specific genes in adolescent versus adult mice that had self-administered oxycodone (Mayer-Blackwell et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014, 2015). Studies in adult mice have shown that the magnitude of antinociceptive tolerance is directly related to the level exposure to chronic MOP-r agonists (Kumar et al., 2008). Therefore based on their oxycodone intake, this would have led to the prediction that the adult-oxycodone group would exhibit greater tolerance than the adolescent-oxycodone group, but the opposite profile was tentatively observed here. Therefore the possibility that adolescent oxycodone exposure may result in more prolonged or extensive adaptations than adult oxycodone exposure should be studied in the future. Further studies are needed to explore the underlying neurobiological alterations following adolescent oxycodone SA, and their relationship to differential sensitivity to oxycodone reward and abuse in adulthood.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [1R01DA029147] (YZ) and the Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation (MJK).

We thank Dr. Ann Ho for her help in preparing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The author(s) declare that, except for income received from my primary employer, no financial support or compensation has been received from any individual or corporate entity over the past three years for research or professional service and there are no personal financial holdings that could be perceived as constituting a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Adriani W, Laviola G. Elevated levels of impulsivity and reduced place conditioning with d-amphetamine: two behavioral features of adolescence in mice. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117:695–703. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.4.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen SL, Rutstein M, Benzo JM, Hostetter JC, Teicher MH. Sex differences in dopamine receptor overproduction and elimination. Neuroreport. 1997;8:1495–1498. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199704140-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badanich KA, Adler KJ, Kirstein CL. Adolescents differ from adults in cocaine conditioned place preference and cocaine-induced dopamine in the nucleus accumbens septi. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;550:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogulavsky JJ, Gregus AM, Kim PT, Costa AC, Rajadhyaksha AM, Inturrisi CE. Deletion of the glutamate receptor 5 subunit of kainate receptors affects the development of morphine tolerance. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;328:579–587. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.144121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenhouse HC, Sonntag KC, Andersen SL. Transient D1 dopamine receptor expression on prefrontal cortex projection neurons: relationship to enhanced motivational salience of drug cues in adolescence. J Neurosci. 2008;28:2375–2382. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5064-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers RA, Taylor JR, Potenza MN. Developmental neurocircuitry of motivation in adolescence: a critical period of addiction vulnerability. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1041–1052. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Boettiger CA. Impulsivity, frontal lobes and risk for addiction. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;93:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham MG, Bhattacharyya S, Benes FM. Amygdalo-cortical sprouting continues into early adulthood: implications for the development of normal and abnormal function during adolescence. J Comp Neurol. 2002;453:116–130. doi: 10.1002/cne.10376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z, Cao J, Xu L. Opiate withdrawal modifies synaptic plasticity in subicular-nucleus accumbens pathway in vivo. Neuroscience. 2007;144:845–854. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Miech RA. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2015: Volume II, College Students and Adults Ages 19–55. Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; Ann Arbor: 2016. p. 427. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Sunkaraneni S, Sirohi S, Dighe SV, Walker EA, Yoburn BC. Hydromorphone efficacy and treatment protocol impact on tolerance and muopioid receptor regulation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;597:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer-Blackwell B, Schlussman SD, Butelman ER, Ho A, Ott J, Kreek MJ, Zhang Y. Self administration of oxycodone by adolescent and adult mice affects striatal neurotransmitter receptor gene expression. Neuroscience. 2014;258:280–291. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.10.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami K, Hasegawa M, Ito H, Nakamura A, Tomii T, Matsumoto M, Orita S, Matsushima S, Miyoshi T, Masuno K, Torii M, Koike K, Shimada S, Kanemasa T, Kihara T, Narita M, Suzuki T, Kato A. Morphine, oxycodone, and fentanyl exhibit different analgesic profiles in mouse pain models. J Pharmacol Sci. 2009;111:60–72. doi: 10.1254/jphs.09139fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niikura K, Ho A, Kreek MJ, Zhang Y. Oxycodone-induced conditioned place preference and sensitization of locomotor activity in adolescent and adult mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2013;110:112–116. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seip-Cammack KM, Reed B, Zhang Y, Ho A, Kreek MJ. Tolerance and sensitization to chronic escalating dose heroin following extended withdrawal in Fischer rats: possible role of muopioid receptors. Psychopharmacol Berl. 2013;225:127–140. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2801-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seip KM, Reed B, Ho A, Kreek MJ. Measuring the incentive value of escalating doses of heroin in heroin-dependent Fischer rats during acute spontaneous withdrawal. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;219:59–72. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2380-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear L. Modeling adolescent development and alcohol use in animals. Alcohol Res Health. 2000a;24:115–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000b;24:417–463. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teicher MH, Gallitano AL, Gelbard HA, Evans HK, Marsh ER, Booth RG, Baldessarini RJ. Dopamine D1 autoreceptor function: possible expression in developing rat prefrontal cortex and striatum. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1991;63:229–235. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(91)90082-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teicher MH, Krenzel E, Thompson AP, Andersen SL. Dopamine receptor pruning during the peripubertal period is not attenuated by NMDA receptor antagonism in rat. Neurosci Lett. 2003;339:169–171. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)01475-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theberge FR, Pickens CL, Goldart E, Fanous S, Hope BT, Liu QR, Shaham Y. Association of time-dependent changes in mu opioid receptor mRNA, but not BDNF, TrkB, or MeCP2 mRNA and protein expression in the rat nucleus accumbens with incubation of heroin craving. Psychopharmacol Berl. 2012;224:559–571. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2784-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurgelun-Todd D. Emotional and cognitive changes during adolescence. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Brownstein AJ, Buonora M, Niikura K, Ho A, Correa da Rosa J, Kreek MJ, Ott J. Self administration of oxycodone alters synaptic plasticity gene expression in the hippocampus differentially in male adolescent and adult mice. Neuroscience. 2015;285:34–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Mayer-Blackwell B, Schlussman SD, Randesi M, Butelman ER, Ho A, Ott J, Kreek MJ. Extended access oxycodone self-administration and neurotransmitter receptor gene expression in the dorsal striatum of adult C57BL/6 J mice. Psychopharmacol Berl. 2014;231:1277–1287. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3306-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Picetti R, Butelman ER, Schlussman SD, Ho A, Kreek MJ. Behavioral and neurochemical changes induced by oxycodone differ between adolescent and adult mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:912–922. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Bendor J, Hofmann L, Randesi M, Ho A, Kreek MJ. Mu opioid receptor and orexin/hypocretin mRNA levels in the lateral hypothalamus and striatum are enhanced by morphine withdrawal. J Endocrinol. 2006;191:137–145. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]