Abstract

With the growing adoption and implementation of multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) in school settings, there is increasing need for rigorous evaluations of adaptive-sequential interventions. That is, MTSS specify universal, selected, and indicated interventions to be delivered at each tier of support, yet few investigations have empirically examined the continuum of supports that are provided to students both within and across tiers. This need is compounded by a variety of prevention approaches that have been developed with distinct theoretical foundations (e.g., Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, Social-Emotional Learning) that are available within and across tiers. As evidence-based interventions continue to flourish, school-based practitioners greatly need evaluations regarding optimal treatment sequencing. To this end, we describe adaptive treatment strategies as a natural fit within the MTSS framework. Specifically, sequential multiple assignment randomized trials (SMART) offer a promising empirical approach to rigorously develop and compare adaptive treatment regimens within this framework.

Keywords: Multi-tiered Systems of Support, SMART, Adaptive Treatment Strategies, Behavioral Support

There has been an increasing focus on the topic of school mental health in recent years and increasing efforts to address “non-academic barriers to learning.” Estimates suggest that 20% of students receive some form of school mental health service (Foster et al., 2005) with continued growth in that proportion in recent years. However, mental health challenges remain frequently under identified, making systems-level school-wide mental health promotion and prevention efforts absolutely critical (Flett & Hewitt, 2013). In this domain, student needs are diverse, ranging from internalizing problems, substance use problems, to externalizing problems. Referrals to community healthcare agencies for assessment and/or treatment services are time-consuming, expensive, and do not readily translate into interventions or accommodations that can be offered in school settings. Similarly, mandated school services such as special education and alternative learning placements require special qualifications, are costly, and available only to students with the most serious behavioral and emotional problems. Increasingly, schools have taken ownership of student mental health needs and have adopted multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) in an effort to provide proactive, comprehensive and evidence-based supports. Typically, conceptualized as a three-tiered model, the MTSS framework provides layered interventions that begin with universal, school-wide programming and increase in intensity and differentiation depending on the students’ response to preceding interventions (Fletcher & Vaughn, 2009). Examples of such models include Response to Intervention (RTI) and Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS). These models apply a systematic and empirically-driven MTSS framework to ensure that students receive more timely and effective services (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2006; Hawken, Vincent, & Schumann, 2008).

For example, when schools apply MTSS to student behavior, Tier 1 interventions generally consist of a school-wide code of behavioral expectations that are explicitly taught to all students and reinforced. All students regardless of their degree of risk are exposed to a general classroom management system including clear behavioral expectations and supports (i.e., universal intervention). Students showing an inadequate response (i.e., continue to display behavioral problems) are stepped-up to targeted and more intensive Tier 2 interventions. Tier 2 behavioral interventions typically consist of more focused support programs that are often delivered in a small group format, such as manualized programs like Coping Power (Lochman & Wells, 2002), social skills training, or efficient individual interventions such as behavior contracts or Check-in/Check-out (CICO). Last, students who are unresponsive to small group intervention and continue to struggle with their behavior are stepped-up to Tier 3 interventions. These are the most intensive and often provide function-based individualized behavioral intervention plans or involve referral for special education services (Crone, Horner, & Hawken, 2004). These tiered supports are additive, in that lower-level supports are still available to students requiring support at higher tiers. Critical to the MTSS framework is the monitoring of students’ response to the interventions with data-based measures and establishing criteria for transitioning between levels of support (Gresham, 2005; Sugai, Horner, & Gresham, 2002). As the implementation of MTSS continues to proliferate in educational settings, there exists significant opportunity to support student mental health in ways not previously realized. Advocacy and federal directives for providing students with school-based mental health services have reinforced this movement in addressing the mental health needs of students (U.S. Department of Education, 2003).

As described, a foundational component of the MTSS framework involves the delivery of evidence-based programs. Consequently, there has been increasing pressure placed on schools to import evidence-based prevention and treatment programs in response to students’ mental health needs (Langley, Nadeem, Kataoka, Stein, & Jaycox, 2010). Indeed, there are a growing number of evidence-based programs established for use in school settings (Forman et al., 2013). These programs typically address behavioral, social, and emotional factors assumed to cause or exacerbate disruptive, noncompliant and aggressive behavior (Wilson & Lipsey, 2007), although a growing number address mental health more broadly (e.g., emotion regulation, trauma, depression, anxiety). Programs feature a variety of modalities including classroom-wide support systems and behavioral health curricula, small group socio-emotional skills training and peer support, and comprehensive, multicomponent programs that typically integrate training for child, parent, and teacher (August, Bloomquist, Realmuto, & Hektner, 2007; August, Realmuto, Winters, & Hektner, 2001). To standardize and facilitate delivery, these programs are generally delivered with uniform composition, dosage, and duration to students regardless of their individual risks and needs (August, Gewirtz, & Realmuto, 2011). This “one size fits all” approach while expedient to deliver assumes that all children have similar needs. Despite their intuitive appeal and evidence base, such programs have yielded only modest effect sizes with considerable variability in individual response (Rones & Hoagwood, 2000). Such performance has led some researchers to call for more adaptive, customized approaches that are tailored to the individual needs of youth (Collins, Murphy, & Bierman, 2004).

Adopting a more tailored problem-solving approach to service delivery is consistent with the basic tenets of MTSS as a proactive and responsive framework, yet efficiency and feasibility are also very real and important concerns. For example, we must also avoid the “program for every problem” phenomenon (Domitrovich et al., 2010). Thus, determining how to deliver a tailored, problem-solving approach while maintaining efficiency and feasibility is a challenge. Additionally, while this framework offers a promising approach for providing students with the services they need, there are few guidelines for (a) selecting the most appropriate interventions for each tier, (b) determining how best to sequence the interventions in a tiered approach, and (c) how to determine the best intervention sequence for any individual student. These challenges are compounded by the emergence of programs developed with differing theoretical orientations. For example, interventions implemented within the context of PBIS are grounded in behavioral principles, while interventions implemented within the context of social-emotional learning (SEL) are grounded in the principles of positive youth development. These challenges make it incredibly difficult for school professionals to determine which programs to implement in their settings, and which programs will yield the greatest effects for their student population.

Against this backdrop, the present article describes an emerging innovation in the development and validation of precision-based interventions for youth who experience social, emotional, and behavioral impairments and need additional support. This approach is referred to as adaptive treatment strategies (ATS [also known as dynamic treatment regimes]). ATS apply principles similar to those used in MTSS to tailor each individual’s intervention over time based on assessment of ongoing response but extend these models in several ways. For example, ATS specify (a) which intervention option to offer first, (b) at what time point response should be assessed and interventions adjusted, and (c) which intervention option should be offered if there is nonresponse to the first intervention option. Intervention options may vary in intensities, types, and/or modalities. The construction of these decision rules is aided by an innovative research methodology called sequential multiple assignment randomized trials (SMART). SMART empirically evaluates multiple intervention sequences and associated decision rules within a single trial in order to identify optimal ATS. In the text that follows we (a) present the rationale for ATS, (b) describe the SMART technology used to operationalize ATS, (c) describe a SMART prototype currently being delivered by a community agency to preempt the development of conduct disorder among at risk youth, and (d) describe an example of how schools might apply a SMART to evaluate multi-tiered interventions to prevent or deescalate behavior problems.

Adaptive Treatment Strategies (ATS)

ATS use ongoing information about an individual (e.g., changes in behavioral status) to make subsequent intervention decisions through the use of decision rules (i.e., algorithms). See Table 1 for several recommend articles in the area of ATS. Decision rules specify how the composition and/or intensity of an intervention should be adjusted at critical decision points such as when an individual is not responding to a current intervention (August, Piehler & Bloomquist, 2014; Lei, Nahum-Shani, Lynch, Oslin, & Murphy, 2012). As such, ATS resemble ‘real-world’ practice where practitioners often change treatments when an individual fails to demonstrate a desired response, absent empirically established decision rules. With ATS, recommendations for adjusting treatment are based on individual characteristics that are collected and measured during treatment, such as “has the individual exhibited significant symptom reduction” or “has the individual reached a specified level of adaptive functioning?” When an individual displays no response or possibly a suboptimal response, practitioners may readjust the intervention plan by increasing dosage or switching to a different intervention. This time-varying approach is particularly useful for the treatment of chronic disorders such as depression (Lavori, Dawson, & Rush, 2000), Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD; Pelham et al., 2016), and alcohol and drug dependence (Krantzler & McKay, 2012). ATS may also have a role as a prevention tool by redirecting risk trajectories for children or youth deemed to be at heightened risk for conduct disorder (August et al., 2014).

Table 1.

Recommended Articles Regarding Adaptive Treatment Strategies and SMART

| Area | Citation |

|---|---|

| Overview of Adaptive Treatment Strategies | Collins, Murphy, & Bierman (2004) |

| Overview of SMART Designs |

Lei, Nahum-Shani, Lynch, Oslin, & Murphy (2012) Almirall, Nahum-Shani, Sherwood, & Murphy (2014) |

| Applications of SMART Designs | Gunlicks-Stoessel, Mufson, Westervelt, Almirall, & Murphy (2015) Pelham et al., (2016) Kasari et al. (2014) |

Systematically incorporating empirically-derived ATS within the MTSS framework appears to be a natural fit. With both approaches, the goal is to adapt intervention options based on an individual’s progress to a specific goal. Underlying the MTSS framework, an individually-oriented four-stage problem-solving model is frequently utilized (Kratochwill & Bergan, 1990). These stages entail identification of a problem, problem analysis, intervention implementation, and intervention evaluation. This problem-solving process allows for careful selection of appropriate intervention programming based on student needs and evaluation of program effects. Indeed, in many ways ATS could be considered a systematic extension of this approach within MTSS. We propose that there is value added to incorporating the ATS paradigm as a mechanism for studying MTSS. ATS is consistent with the underlying rationale for MTSS, with a central aim being to ensure that all youth are able to access the services they need. In particular, within the context of MTSS, researchers often evaluate evidence-based interventions in isolation as standalone programs, with little attention to how a series of interventions perform either within tiers or in combination across tiers of support (i.e., synergistic effects). Thus, a disconnect exists between how these interventions are evaluated and how they are delivered within MTSS. Such research is imperative in order to help bridge the research-to-practice gap and is consistent with growing interest in implementation science in school settings (Owens et al., 2014).

Furthermore, the MTSS emphasis on theoretically-informed intervention planning is highly germane to the development and implementation of ATS. Within MTSS, a problem-solving approach is often implemented, including a problem analysis stage, which involves the identification of specific, potentially malleable, causal factors maintaining a problem (Kratochwill & Bergan, 1990). In turn, this analysis informs the selection of more appropriate and precise interventions. Similar to intervention selection with the problem-solving approach, intervention programs utilized within ATS typically consist of interventions that target common theoretically-derived mechanisms of problems. Within ATS however, empirically-derived decision rules utilizing individual characteristics may guide the selection of intervention programming. For example, an assessment of problem behavior may reveal specific established etiological pathways (e.g., social skill deficits or poor emotion regulation) contributing to such behaviors in an individual student. A decision rule will guide the selection of an ATS that employs an intervention empirically demonstrated to most effectively target the identified key contributing factors. Thus, ATS allow for a process of theoretically-derived decision making that is guided by empirical evidence.

Finally, a hallmark of MTSS and the associated problem-solving approach involves student response to intervention, yet very little is known regarding non-responders in the current landscape. Research examining more precise and appropriate interventions for students who are unresponsive to intervention is critical to advance prevention efforts. A number of researchers have pioneered work in this vein, particularly in the area of reading (e.g., Connor et al., 2009; Torgesen, 2000). However, in educational settings, social, emotional and behavioral domains have received considerably less attention. It could be argued that, in many ways, evidence-based practices do not currently exist for non-responsive students. Indeed, within traditional group-based research methodology, little attention is typically paid to non-responders. That is, when an intervention is found to produce a positive main effect, there are likely students participating in the intervention group who either (a) did not change or (b) actually declined in performance. We should attend to and be concerned about these students and seek to develop more adaptive, precise and effective interventions. Such precision-based care is at the conceptual core of an MTSS framework: many consider MTSS to be a needs-driven, equity based approach to ensuring that all children receive the supports they need to be successful. Instead, in practice, a trial-and-error approach to modifying subsequent efforts is typically employed. For example, school-based teams my decide to change any number of elements, including (a) the format of delivery for students unresponsive to intervention (small group versus individual), (b) dosage frequency or intensity, and/or (c) implement a different intervention entirely. Adaptive treatment strategies offer a promising and rigorous approach to the study of intervention delivery and tailoring to promote positive outcomes for all students, but particularly for those with the greatest need.

SMART Technology

While schools implementing MTSS might employ ATS in their delivery, the embedded ATS may not have undergone rigorous evaluation and optimization. In constructing ATS, questions that need to be addressed include the best sequencing of interventions when individuals are not responding and the best time to evaluate response. Construction of such high-quality ATS can be achieved with an innovative type of research design referred to as sequential multiple assignment randomized trials (SMART; Almirall, Nahum-Shani, Sherwood, & Murphy, 2014; Lavori & Dawson, 2008; Murphy, Oslin, Rush, & Zhu, 2007). A SMART design is implemented in multiple stages with individuals randomized multiple times to various intervention options across stages (see Lei et al., 2012). Sequenced randomizations ensure that at each decision point, the groups of participants assigned to each of the intervention options are balanced in terms of participant characteristics. In the examples provided below each youth is randomized twice, initially and then again once it is known whether the youth is a responder or a non-responder to the initial intervention. It is important to note that even though the SMART experimental design involves randomization, once ATS have been developed, their delivery in customary practice does not involve randomization. Each randomization stage within the SMART becomes in the ATS a key time point where a decision is made as to whether to adjust the intervention. Data from the SMART are used to construct empirically-derived decision rules that may be utilized within these time points as a part of the ATS. See Table 1 for recommended articles providing an overview and applications of SMART designs.

The selection of appropriate interventions is critical in the creation of effective ATS. Possible intervention options may reflect different types of conceptual orientations (behavioral-based contingency systems vs. socio-emotional skills training), different intervention foci (youth vs parent), different modes of delivery (classroom, small group, individual, parent/family), different levels of dosage/intensity, and/or different approaches to increase engagement and adherence to the intervention. The goal is to operationalize decision rules such as—begin with intervention type X, if the individual shows favorable response, step-down to maintenance; if the individual shows a poor response, step-up to intervention Y. Depending on the number of decision points and the number of intervention options to consider at each decision point, multiple ATS can be derived from any one SMART. Set up in this way, a SMART allows researchers to answer key tactical questions, such as “What is the best first stage intervention option,” “What second stage intervention option is best for individuals who do not show satisfactory response to the first stage intervention option,” “Which sequence of intervention options yields the best outcomes?” This approach allows for an examination of “downstream” or synergistic effects whereby an initial intervention component enables an individual to benefit more substantially from subsequent intervention components (Murphy, Oslin et al., 2007). By evaluating different first-stage, second-stage, and overall sequences of interventions, a SMART allows us to systematically identify which approach may be most effective in addressing the diverse needs and risk factors of a population.

In addition to tailoring intervention sequences based on assessment of ongoing response, SMART can further increase precision by identifying potential tailoring variables that reflect pre-intervention individual characteristics. By measuring personal characteristics before initiating services, researchers may evaluate these characteristics for their utility in predicting differential response to the various intervention sequences. If successfully identified, these personal characteristics could then serve as secondary tailoring variables to match individuals with their optimal intervention. Potential secondary tailoring variables may include gender, age, SES, as well as biomarkers, personality traits and psychosocial risk factors. When validated in SMART, these secondary tailoring variables can be integrated into the derived ATS. As such, these data help answer the question, “What works best for whom?”

ATS derived through SMART may be applied both within and across MTSS tiers. Within tiers, an ATS may inform the section of an optimal intervention strategy for a particular youth at that level of support. Strategies within tiers may be selected based on knowledge of a best intervention option within a combination of interventions offered. Individual tailoring variables may also be used to select an optimal intervention strategy for a particular youth within a tier of support. Across tiers, ATS will provide a standardized approach to evaluate non-response within a particular tier and the appropriate subsequent more intensive intervention to be offered at a higher tier. By providing decisions rules dictating intervention selection, identification of non-responders, and intervention sequence, ATS have the potential to build more consistent empirical guidance across the MTSS framework.

Executing a SMART Design

Juvenile Diversion Agency: The Community Prototype

In this section we present a description of a community-based implementation of a SMART design (see August et al., 2014). The intent is to provide the reader with the rationale and approach for constructing ATS as a programming framework for a high risk youth population (diversion youth) and an illustration of how a SMART design was crafted to operationalize ATS. A collaborative partnership between a youth-serving agency and a university-based team of research investigators implemented this project. The agency serves the county attorney’s office by providing pre-court diversion programming for juvenile offenders who have been cited by law enforcement for various status and misdemeanor offenses including shoplifting, vandalism, disorderly conduct, underage drug use, and assault but have not yet established a pattern of serious and chronic antisocial behavior or have been formally adjudicated. Diversion serves as a key portal for identifying at-risk youth, many of whom are at heightened risk for developing Conduct Disorder (CD) as well as depression, anxiety disorders, and substance use disorders (Wareham, Dembo, Poythress, Childs, & Schmeidler, 2009). The standard practices for diversion agencies are to require restitution, community service, or simply to warn-and-release. Although these punitive interventions satisfy the public demand for accountability, there is little evidence that they prevent escalation of conduct problems or progression to more serious mental disorders (Patrick & Marsh, 2005; Wilson & Hoge, 2013). An alternative to restorative justice programs is a life-skills approach that emphasizes the acquisition of strengths and the building of human capital in order to maximize the likelihood that youth offenders will veer away from a delinquent lifestyle toward more conventional goals (Guerra, Williams, Tolan, & Modeski, 2008). In light of the increasing emphasis on evidence-based programs for prevention and treatment of youth conduct problems, the collaborative community agency/research team opted to select interventions with an evidence-base for reducing conduct problems. There is overwhelming evidence that youth problem-solving skills training and/or parent behavioral management skills training are effective interventions in this domain (Kazdin, 2010).

The collaborative further recognized that diversion counselors confront additional intervention challenges as a result of the heterogeneity in the diversion population. The diversion population includes youth who may be one-time offenders and at minimal risk for future offending, periodic offenders who are at moderate risk for future offending, as well as chronic offenders who are at heightened risk for serious and chronic offending. Consequently, conventional interventions that apply a “one size fits all approach” are unlikely to be effective in addressing these diverse individuals. Moreover, providing interventions to youth that are incongruent with their needs and motivations can result in low levels of engagement and dropout (Kazdin & Wassell, 1999) as well as negative peer contagion effects particularly when programs are provided using a group format (Dodge, Dishion, & Lansford, 2006). It stands to reason that new and creative approaches are needed. With these considerations in mind, the collaborative produced the following guidelines to assist in their efforts to produce an effective and efficient intervention framework:

Youth (and their families) referred by law enforcement for juvenile diversion programming are not help-seekers in the traditional sense. Thus, youth and their families must perceive intervention options offered to them as relevant to their needs and administered with minimal burden.

In light of the varying degrees of risk for continued offending among a diversion population (heterogeneity), an adaptive intervention approach in which intervention options are tailored to the youths’ risk profiles may produce the best outcomes.

An efficient and cost-effective adaptive intervention approach would feature a sequential, stepped care delivery system in which youth receive only the intervention(s) they need.

In order to construct optimal adaptive treatment strategies (ATS), SMART design technology will be used. Youth are randomized to two brief-type intervention options at the first tier. Responders are stepped- down and monitored over time while non-responders are stepped-up and randomized to more intensive interventions at the second tier.

In lieu of conventional punitive interventions, diversion counselors will offer strength-based skills training interventions with the primary orientation being motivational enhancement coupled with the teaching of decision-making skills.

Because youth-focused and parent-focused skills training modalities have been validated in previous prevention and treatment research addressing conduct problems, both foci will be compared across intervention tiers.

In order to assess intervention response, diversion counselors will use an empirically-based response assessment tool. The tool will include measures that assess the youth’s risk trajectory leading to conduct disorder.

Interventions

The collaborative selected two evidence-based intervention options to construct the ATS. The Teen Intervene program (TI; Winters & Leitten, 2007) is a youth-focused intervention that includes motivational enhancement, prosocial goal-setting, and training in responsible decision-making and social problem-solving with the goal of choosing attitudes and behaviors that are healthier alternatives to antisocial behaviors. The Everyday Parenting program (EP; Dishion, Stormshak, & Kavanaugh, 2011) is a parent/family-focused intervention that addresses three broad areas of parent/family skills building: (a) behavioral management support in the form of contingent positive reinforcement and punitive consequences to help regulate adolescent behaviors; (b) limit setting and supervision of youths’ activities, whereabouts, and peer affiliations to minimize opportunities for inappropriate or dangerous risk-taking; and (c) family interaction skills to facilitate parent-adolescent communication and problem-solving to facilitate responsible decision-making. Both programs can be modified to be delivered in “brief” and “extended” formats. The brief versions include two or three sessions and include motivational-interviewing concepts that may be especially effective as first-tier intervention options, particular for youth at low risk for escalation of conduct problems (Jensen et al., 2011). Extended models are best suited for youth at moderate to higher degrees of risk, include an additional three-to five sessions, and provide intensive skills training.

Response Assessment Tool

As noted above, ATS tailor treatment via decision rules that specify how the intensity or type of intervention should be adjusted depending on individual characteristics that indicate a satisfactory response to the current intervention. Measuring students’ responsiveness and establishing criteria for transitioning between tiers is critical to the performance of a SMART design. For treatment-based intervention systems delivered in clinic setting, the logical candidate would be a reduction in problem behaviors (e.g., noncompliance, fighting) or functional impairments (e.g., poor peer interactions, academic difficulties). For prevention systems that target high risk, but asymptomatic individuals, the response indicators are not readily apparent. Successful response may reflect a change in a youth’s risk trajectory (e.g., motivation to change behavior, attitudes toward aggression, norms about the appropriateness of aggressive behavior). To determine intervention responder status with the diversion sample, we used a multi-dimensional risk assessment tool that included measures that reported (a) current conduct problems, (b) current functional impairment, and (c) deviant peer affiliations. To be flagged as at- risk and in need of additional services (i.e., non-responder) following completion of Tier 1 intervention, youth would need to show evidence of any of one of the following criteria: (a) problematic conduct problems > 1 standard deviation (T-Score > 60) as rated by parents on the Behavioral Assessment System for Children [BASC-2]; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004); (b) impaired adaptive functioning as rated by counselors on the Child and Adolescent Functional Assessment Scale (CAFAS [T-Score > 60]; Hodges, 2000); or (c) elevated exposure to deviant peer influences on the Friendship Scale (T-Score > 60; Child and Family Center, 2013a, 2013b). It is important to keep in mind in this example that youth may display some improvement (improve from three to one criterion) but nevertheless remain at elevated risk for serious conduct problems.

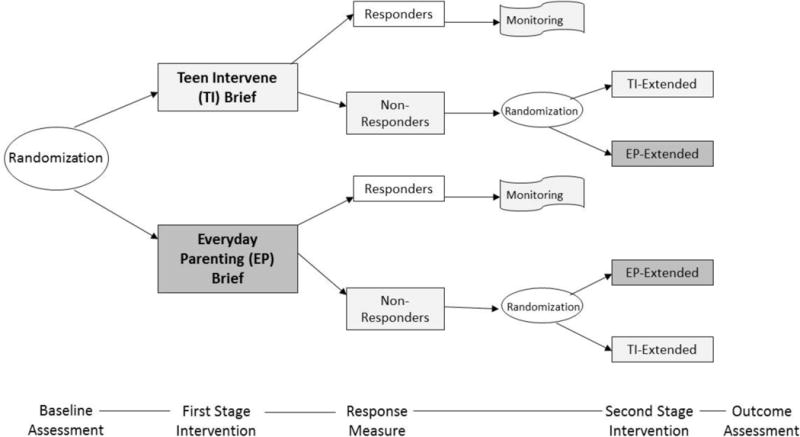

Below we present a visual analogue of a SMART design that was employed in this study. At Stage 1, youth are randomized to either TI-Brief or EP-Brief. Responders to either of the Stage 1 options are stepped-down and monitored over time for maintenance of intervention effects. Non-responders to either of the Stage 1 options are stepped up and re-randomized to tier 2 options, either (a) continuation of the Stage 1 option with increased dosage (TI-Extended or EP-Extended), or (b) switched to the alternative extended intervention option. Based on the number of stages and the number of intervention options, one or more ATS can be embedded within a SMART. The present SMART yields the following four ATS:

Youth-Only Skills Training ATS: Begin with TI-Brief, youth exhibiting a positive response to initial TI-Brief are stepped-down to monitoring, youth exhibiting nonresponse are stepped up to TI-Extended (this is a youth-continuation ATS).

Youth Skills Training then Parent Support ATS: Begin with TI-Brief, youth exhibiting a positive response to initial TI-Brief are stepped-down to monitoring, youth exhibiting nonresponse are stepped-up to EP-Extended (this is a begin with youth then switch to parent ATS).

Parent-Only Support ATS: Begin with EP-Brief, youth exhibiting a positive response to initial EP-Brief are stepped-down to monitoring, youth exhibiting nonresponse are stepped-up to EP-Extended (this is a parent-continuation ATS).

Parent Support then Youth Skills ATS: begin with EP-Brief, youth exhibiting a positive response to initial EP-Brief are stepped-down to monitoring, youth exhibiting nonresponse are stepped-up to TI-Extended (this is a parent then switch to youth ATS).

This SMART design permits several key questions to be addressed:

Which Stage one intervention provides the best response and thus should be offered initially?

Which Stage two intervention provides the best second tier intervention for youth who show non-response to a Stage one intervention?

Which sequential approach provides the best overall response – one that begins with a youth-focused intervention or one that begins with a parent/family-focused intervention?

While this SMART was implemented in a community context with diversion-referred youth, several aspects of this population and design are highly relevant to school settings. First, the significant heterogeneity of the population is also reflected in most school settings. Like diversion youth, students in the classroom may display similar behaviors but have wide range of underlying risk factors maintaining those behaviors. For this reason, incorporating a range of intervention intensities and foci in an ATS is essential to meet these diverse needs. Second, effective engagement of parents in interventions often presents substantial challenges. Parents of diversion youth may resist participating in an intervention because of their perception that the child’s offense was “not the parents’ fault.” Parents of youth exhibiting behavioral problems in a school setting may be similarly resistant to involvement due to their perception of a lack of responsibility for their child’s behavior when at school. Utilizing motivational enhancement and minimizing parental burden of service delivery are two beneficial strategies that can be incorporated into an ATS to increase parental engagement and reduce resistance to services.

Elementary School Context: The School Prototype

As noted above, problem-solving MTSS models such as RTI and PBIS are currently in vogue as a replacement for the traditional “Refer-Test-and Place” model commonly applied by schools to assist high risk youth (Cash & Nealis, 2004). Refinement of these problem-solving models can be informed by innovative research methodologies such as SMART that are currently being employed to construct ATS for individuals suffering with chronic and severe mental health and substance use disorders (Murphy, Lynch, Oslin, McKay, & TenHave, 2007; Shortreed & Moodie, 2012). As this research with SMART is nascent, there are relatively few examples to guide its application in school settings. Existing SMART designs employed in schools have typically focused on children with existing mental health diagnoses rather than more general at-risk populations. While some studies in this area are currently underway, a recently completed SMART study by Pelham et al (2016) provides an example of a partially school-based implementation. This SMART evaluated options for sequencing and dosage of medication and behaviorally-based interventions for elementary school children with ADHD. The study incorporated school-based assessments of intervention response as well as teacher consultation regarding classroom based behavioral management practices. The study provides evidence for the feasibility of utilizing teacher-reported data and observed classroom behavior in determining response within a SMART as well as deploying aspects of SMART-embedded ATS within school settings.

In this section we present a heuristic framework that illustrates how a SMART design might be integrated within a MTSS framework to develop a comprehensive school-based behavioral health support system. The proximal goal of this support system is the reduction of disruptive, noncompliant and aggressive student behavior in the classroom, and the distal goal is prevention of the development of more serious and chronic conduct problems. The proposed behavioral health support system includes two primary intervention tracks that are distinguished by their theoretical orientations. One track includes interventions that reflect an applied behavior analysis approach where school personnel establish reinforcement contingencies to incentivize prosocial behavior and consequences are enforced to extinguish antisocial behavior. This track often addresses children whose risk reflects inherent behavioral regulation vulnerability and exposure to coercive, inconsistent and/or non-contingent environments (Stormshak, Bierman, McMahon, & Lengua, 2000). The second track includes interventions that conform to a SEL skills-based approach in which development of socio-emotional self-regulatory skills are thought to provide children with the competence to successfully negotiate challenging tasks such sharing, cooperating, taking turns, etc. These children may be at risk due to personal vulnerabilities or limited exposure in their environments that result in delayed to deficient skill acquisition in these areas. Each track offers a tiered sequence of interventions which are delivered with increasing levels of intensity and/or comprehensiveness. Each sequence begins with a universal (classroom-based; Tier 1) intervention with either a behavioral or SEL skills focus. To identify the best match for each student for subsequent ATS development, the student is randomized to one of these two universal interventions. Students assessed to show poor response to the initial intervention are transitioned to indicated (small group/individual-based) intervention options that provide focused, intensive and comprehensive behavioral support or SEL skills training for the youth and parenting education for the parents. These indicated interventions are appropriate for Tier 2 within the MTSS framework.

Rationale

A primary mandate of elementary schools is to provide an instructional environment that will promote learning. In pursuing this mandate, teachers are often required to manage disruptive behaviors in their classrooms and increasingly are being requested to deliver prevention-oriented curricula that address personal and societal challenges experienced by children (e.g., alcohol and other drug use, unsafe sexual practices). Given the rising prevalence rates of mental health problems in the general child population and the high costs of placing students in special education programs or alternative learning placements, there is an increasing call for school-wide prevention programs to address these concerns (Greenwood, Horner, & Kratochwill, 2008). Furthermore, research suggests that early-onset behavior problems are a precursor to adolescent delinquency, substance use, and school dropout (Moffitt, 2006; Patterson, DeBaryshe, & Ramsey, 1989). Given the myriad of negative outcomes associated with students who go on to receive an EBD diagnosis (see Bradley, Doolittle, & Bartolotta, 2008), prevention programs are essential in order to improve lifelong trajectories for these students.

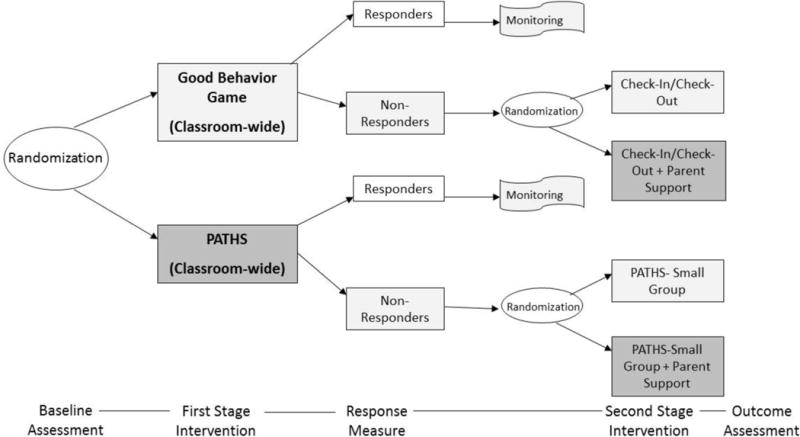

While the MTSS framework provides various levels of support to meet the needs of individual students it does not necessarily specify the best intervention for a student at a particular tier or the optimal sequence of interventions across multiple tiers for those showing nonresponse to previous tiers. SMART technology can be of considerable value in evaluating the efficacy of various interventions embedded within the MTSS framework. Figure 2 provides a visual conceptualization of a SMART design to create a preventive behavioral health system in an elementary school context.

Figure 2.

Proposed SMART design for use within an elementary school.

Interventions

The SMART design compares two primary tracks, one featuring behavioral support strategies and the other featuring socio-emotional learning (SEL) training. Each track includes an initial universal Tier 1 intervention and two possible Tier 2 interventions, each consistent with the general intervention orientation of the overall track.

Behavioral Support Track – 1st Tier: The Good Behavior Game (GBG)

This universal program can be used to reinforce appropriate social and classroom behavior in an elementary school setting (Barrish, Saunders, & Wolf, 1969). The program is grounded in applied behavior analysis with the goal to reduce disruptive, noncompliant and aggressive behavior (e.g., getting out of seat, talking out of turn, not following directions, hitting other students). Classrooms are divided into teams, and each team can earn rewards if the entire team is “on task” (e.g., fewer than a specified number of rule violations during the game period) or otherwise behaving in compliance with specified teacher expectations. The teacher monitors students’ behaviors during the game. Teachers record inappropriate behaviors with ‘checks’ on a scoreboard. At the end of each week the teacher rewards teams who received fewer than five checks throughout the week. Rewards include stickers on charts, extra free time, and special team privileges. A review of research conducted with the GBG by Embry (2002) concludes that the GBG produces significant reductions in disruptive behavior and increased academic engaged time. Kellam and colleagues evaluated both the short- and long-term effects of the GBG in randomized trials conducted in urban elementary schools in Baltimore (Kellam et al., 1991; Kellam, Rebok, Ialongo, & Mayer, 1994). Students demonstrated reductions in disruptive and aggressive behavior as early as grade one (Kellam et al., 1994). Long-term effects assessed at ages 19–21 showed that the GBG significantly reduced the risk of alcohol or illicit drug abuse (Kellam et al., 2008) and use of mental health and drug services (Poduska et al., 2008).

Behavioral Support Track – 2nd Tier Option 1: Check-In/Check-Out (CICO)

CICO (also known as the Behavior Education Program) is an evidence-based Tier 2 intervention developed for students who are unresponsive to universal supports such as the GBG (Crone, Hawken, & Horner, 2010). Consistent with the GBG, CICO is also based upon the principles of contingency management and provides students with frequent and timely feedback regarding their behavior throughout the school day. The components of CICO include (a) a Daily Progress Report (DPR) card that the student utilizes throughout the day to obtain feedback regarding behavioral expectations and earn points toward a reward, (b) a morning check-in with a school staff member during which the student is provided with the DPR and positive adult attention and is encouraged to meet behavioral expectations, (c) structured teacher feedback at the end of each class period utilizing the DPR, (d) an end-of-day check-out meeting with a school staff member to determine points earned and progress toward goals – if goals are met, reinforcement is delivered, and (e) the DPR is then brought home, shared with guardians, signed, and returned the following day (Crone et al., 2010). One of the advantages of CICO is that it is continuously available to students, and they can phase in and phase out of the program as needed. Numerous studies have supported the effectiveness of CICO in reducing problem behavior, with some estimates suggesting CICO was effective for 65–75% of students who participated in the program (e.g., Filter et al., 2007; Hawken, MacLeod, & Rawlings, 2007; Lane, Capizzi, Fisher, & Ennis, 2012).

Behavioral Support Track – 2nd Tier Option 2: CICO + Parent Support

An adapted version of CICO could be delivered to include (a) parent training in CICO and (b) parent reinforcement in addition to the standard delivery approach described above. These adaptations would allow for school personnel to provide more comprehensive support to students across multiple settings. The DPR component implemented in CICO is consistent with research on Daily Behavior Report Cards (DBRC), which are typically utilized as an individually tailored intervention strategy (Volpe & Fabiano, 2013). In a recent meta-analysis of research on DBRCs, Vannest, Davis, Davis, Mason, and Burke (2010) found that studies incorporating a high degree of home-school collaboration were significantly more effective than studies that did not.

SEL Skills Training Track – 1st Tier: Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies (PATHS)

This is a SEL curriculum that teaches elementary school children about emotion, self-control, and problem-solving using the PATHS ABCD model (Kusche & Greenberg, 1994). The ABCD acronym signifies the following domains:

Affective: emotional understanding and control.

Behavioral: skills and control.

Cognitive: understanding choice, making decisions, taking responsibility.

Dynamic: putting it together with self-esteem and personality.

PATHS is typically administered as a classroom-wide universal program. The curriculum consists of 60 lessons on emotional and interpersonal understanding, including identifying and appreciating various affective states, and how to control emotions. A Control Signals Poster, modeled after a stop sign with red yellow, and green lights, teaches students emotional control and problem-solving in difficult social situations. Students learn to stop and try to calm themselves and think about how to handle the situation, how to implement their plan, and how to evaluate their conduct. Greenberg, Kusche, Cook, and Quamma (1995) found that PATHS increased the students’ ability to understand and articulate emotions. Kam, Greenberg, and Kusche (2004) implemented the program with special education classrooms and found that program students had fewer externalizing an internalizing problems as well as a greater decrease in depression when compared to controls. PATHS was also evaluated as a universal intervention in the FAST TRACK study of the prevention of antisocial behavior. Peer sociometric data indicated that PATHS classrooms had lower levels of aggressive and hyperactive behavior and a more positive atmosphere, but they did not differ on teacher ratings of classroom behavior (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1999).

SEL Skills Training Track – 2nd Tier: Option 1: PATHS Child Skills Group

PATHS Child Skills small group training is designed as a targeted intervention for students who are non-responsive to PATHS classroom-based curriculum. This adaptation was included as part of the multicomponent Early Risers “Skills for Success” Program (August et al., 2007). The use of the small group format permits more focused and intensive coverage of the core skills of the PATHS curriculum (emotion regulation) as well as new skill acquisition such as promoting positive peer relationships and friendship including participating, playing fairly, resolving conflict and negotiating. Skill acquisition is supported by modeling, behavioral rehearsal, discussion, role-play and coaching techniques provided by a group facilitator.

SEL Skills Training Track – 2nd Tier: Option 2: PATHS Child Skills Group + Parent Support

As a supplement to the PATHS child component, a parenting component is available that provides parents with information about skills training along with strategies to prompt and reinforce their children’s skill learning in the home (Kusche & Greenberg, 1994). The parent component can be delivered in four sessions with the addition of Parent Letters, a Parent Handbook, and Home Activities. This approach begins with an orientation following by discussion of the ABCD model (see above). Parents receive training and guidance for planning to use new skills (homework) with their child to increase success in helping their child recognize and utilize emotion regulation skills in a home environment. As similar skills are taught in classroom sessions and/or small groups involving the parents creates synergy between child, parent and school, with a focus on emotional understanding and control.

SMART Design

As detailed Figure 1, students are randomized to one of two Tier 1 classroom-administered interventions during stage 1, either the GBG that offers a reinforcement contingency system or the PATHS SEL curriculum. Students are monitored on a quarterly basis on specified criteria. Responders to either Stage 1 option are stepped-down and monitored over time for maintenance of intervention effects. Non-responders to the Stage 1 GBG are stepped-up and re-randomized to one of two second-tier options either (a) Check-in/Check-out (CICO) only or (b) CICO augmented by a parent support component. Non-responders to the Stage 1 PATHS are stepped-up and re-randomized to one of two second-stage options, either (a) continuation of PATHS adapted for small group administration or (b) a modified PATHS augmented by a parent support group. Students who do not respond to either Stage 2 option are referred to the student assistance team for additional evaluation. The present SMART incorporates the following four embedded ATS:

SEL Skills Training ATS 1: Begin with PATHS-classroom, youth exhibiting positive response to PATHS-classroom are stepped-down to monitoring, youth exhibiting nonresponse are stepped- up to PATHS-small group (this is a youth-continuation ATS).

SEL Skills Training ATS 2: Begin with PATHS-classroom, youth exhibiting positive response to initial PATHS-classroom are stepped -down to monitoring, youth exhibiting nonresponse are stepped up to PATH-small group + parent support (this is youth + parent augmentation ATS).

Behavioral Support ATS 1: Begin with GBC-classroom, youth exhibiting positive response to initial GBG classroom are stepped -down to monitoring, youth exhibiting nonresponse are stepped -up to CICO (this is a youth-continuation ATS).

Behavioral Support ATS 2: begin with GBG-classroom, youth exhibiting positive response to initial GBG-classroom are stepped down to monitoring, youth exhibiting nonresponse are stepped up to CICO + parent support (this is a youth + parent augmentation ATS).

Figure 1.

SMART design implemented within a juvenile diversion agency.

Each ATS represent distinct plans of program delivery that school-based practitioners may utilize. By embedding these distinct ATS within the SMART, it is possible to evaluate which adaptive sequence is the most effective in impacting key outcomes. This SMART permits several additional key questions to be addressed: 1. Which first stage intervention provides the best response and thus should be offered initially? 2. Which is the best second stage intervention for youth who show non-response to the first stage intervention? 3. Which sequential approaches provide the best overall response, one that has a behavioral support focus or one that has a socio-emotional skills training focus?

Response Assessment Tool

Responder and non-responder status will be administered quarterly using a multi-method approach. This will include (a) tracking office disciplinary referrals (ODRs), (b) teacher ratings on the 12-item externalizing behavior composite scale of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman 1997; Goodman, 2001), and (c) teacher ratings on the 6-item Impairment Rating Scale (IRS) (Fabiano et al., 2006). There is evidence supporting the use of ODRs in decision-making regarding behavioral support services when implemented as a part of a broader assessment battery, with two or more ODRs most clearly representing an elevated need for services (McIntosh, Campbell, Carter, & Zumbo, 2009). The externalizing composite score of the SDQ has been recommended for progress monitoring (Goodman et al., 2010). The IRS assesses a child’s functioning in six school-related domains including relationship with peers, relationship with teacher, academic progress, self-esteem, influence on classroom functioning, and overall impairment. In each domain the teacher indicates functioning using a 6-point response format with 4 or above indicating functional impairment. The IRS is recommended for use in progress monitoring assessments (Fabiano et al., 2006; Pelham, Fabiano, & Massetti, 2005). A student will be designated a responder if (a) there are one or fewer ODRs, (b) the SDQ externalizing scale is less than one standard deviation above the mean (i.e., a T-score of 59 or below), and (c) five of the six IRS domains are three or lower.

Challenges of SMART Designs and Alternatives

Although we have attempted to articulate the potential benefits derived from well-conducted SMART studies, we would be remiss if we did not note some significant challenges in applying this approach. For example, with a SMART design questions arise concerning how best to monitor individuals for indication of non-response in order to guide subsequent intervention decisions. For children with relatively severe behavioral disorders reduction in symptoms or improvement in adaptive impairments is the standard. However, for less severe child problems or in the case of preventive interventions for at-risk children, interventions are initiated prior to the onset of severe problems and thus there are no ostensible clinical symptoms to be assessed for positive change. Instead, redirection of an at-risk trajectory can be used to make subsequent decisions. Ideally, the risk trajectory would be multi-dimensional and assessed with multiple methods. Such methods might include regular school attendance, improved on-task behavior, reduced classroom disturbances, better peer relations as well as changes in contextual variables such as increased parent-child involvement or improved comportment with teachers. The risk trajectory measure may also combine these variables with level of adherence or engagement with the intervention.

Other practical challenges with SMART designs include the implementation of several potentially new interventions simultaneously. This aspect of a SMART places considerable demands on practitioners in part due to the substantial training time required to learn multiple programs. The implementation of several new programs may also challenge fidelity management as practitioners build their skills in several programs simultaneously. One approach to addressing this issue is to incorporate existing programming (if evidence based) that is already active within the targeted setting into a SMART design for evaluation. This may reduce practitioner training load as well as reduce potential resistance by practitioners or other staff to eliminating existing programming perceived as effective.

SMART represents one innovative framework to tailoring interventions to meet individuals’ intervention needs. Another example is the modular design (Chorpita, Daleiden, & Weisz, 2005). Modules are self-contained functional intervention strategies that can be combined on the basis of an individual’s needs (i.e., multiple problems). Decision-making flowcharts guide which modules to use and when to use them for a particular individual. Accordingly, different interventions for any two individuals may involve different modules or similar modules in a different order. An example from the treatment literature is the Modular Approach to Therapy for Children with Anxiety, Depression, Trauma or Conduct Problems (MATCH) which targets youth who have any one, or combination of these problems (Chorpita & Weisz, 2009). MATCH provides evidence-based therapies for each of these four problems as free-standing modules. Four decision flowcharts, each designed for one primary problem, but containing modules from all four evidence-based treatments, guide therapists’ use of modules in a flexible manner. The individual’s primary problem is used to select a flowchart, which prescribes core modules from the evidence-based therapies for that problem. The therapist may repeat some core modules or add modules from other evidence-based therapies based on the individual’s response to treatment or presence of comorbid problems. In an RCT, MATCH outperformed usual care, whereas standard evidence-based therapies (i.e., three separate single problem evidence-based therapies did not (Weisz et al., 2012). Conceivably, modularity as an intervention design principle may offer promise for personalized innovations that seek to achieve an optimal balance of flexibility and structure.

While modular designs may include adaptive components (e.g., additional modules available for poor responders), the associated decision making process in these designs has not generally undergone rigorous empirical evaluation. Indeed, such designs could be quite amenable to optimization through SMART evaluation. Different modules each demonstrate independent effectiveness, but specific combinations or sequences for non-responders have often not been evaluated. Practitioner decision making could be enhanced by identification of specific sequences of modules as being most effective for particular individuals or specific modules offering additional benefit to those who responded poorly to an initial module.

Conclusion

While MTSS frameworks offer varying levels of support to students based upon their response to intervention efforts, these models often include intervention sequences that have not been specifically tested or optimized for individual students. SMART designs offer the opportunity to increase precision within these models by empirically deriving ATS most likely to be effective for specific students. Community-based SMARTs offer a compelling example of these complex study designs and the variety of questions that could be addressed with the extension of these designs to school settings. The proposed school-based SMART would provide the opportunity to empirically address questions regarding both optimal intervention targets (i.e., behavioral support versus socioemotional skills training), the identification of responders and non-responders to universal interventions, and optimal sequences for individual students (e.g., the impact of parent involvement for non-responders to universal interventions). The incorporation of this type of information into existing MTSS frameworks may improve outcomes and reduce the burden and cost of delivering ineffective services. By using this increasingly precision-based approach to supporting student needs, schools may be able to most effectively and efficiently ensure student success.

We implore researchers to consider applications of SMART designs to the study of MTSS in order to advance the science of truly responsive service delivery frameworks, thus optimizing and delivering precision-based services in school settings. The development and application of new and innovative research methodologies such as these requires training for successful implementation. Thus, we recommend training and self-study for those interested in utilizing these designs.

Schools have significant potential and opportunity to lead prevention efforts for children and youth, and never before has there been a better time to harness that opportunity within the current climate of MTSS and emphasis on school mental health. We see tremendous promise with the development of systematic adaptive treatment strategies embedded within MTSS. Despite the proliferation of evidence-based interventions in recent years, there remain significant limitations in our knowledge and understanding of how to best structure and implement true prevention efforts that systematically target all students within and across tiers of support. SMART designs offer a promising approach to address numerous and diverse questions related to the development of adaptive treatment strategies within an MTSS framework. The time is ripe for advancing the science of MTSS through the use of such designs, which may pave the way for a new era of research regarding precision-based care in school settings.

Acknowledgments

NIMH grants P20 MH085987 and R34 MH097832 awarded to Gerald J. August provided funding for the content described in this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Gerald J. August, Department of Family Social Science, University of Minnesota

Timothy F. Piehler, Department of Family Social Science, University of Minnesota

Faith G. Miller, Educational Psychology, University of Minnesota

References

- Almirall D, Nahum-Shani I, Sherwood NE, Murphy SA. Introduction to SMART designs for the development of adaptive interventions: With application to weight loss research. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2014;4:260–274. doi: 10.1007/s13142-014-0265-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- August GJ, Bloomquist ML, Realmuto GR, Hektner JM. The early risers “skills for success” program: A targeted intervention for preventing conduct problems and substance abuse in aggressive elementary school children. In: Tolan P, Szapocznik J, Sambrano S, editors. Preventing youth substance abuse. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2007. pp. 137–158. [Google Scholar]

- August GJ, Gewirtz A, Realmuto GR. Moving the field of prevention from science to service: Integrating evidence-based preventive interventions into community practice through adapted and adaptive models. Applied and Preventive Psychology. 2010;14:72–85. [Google Scholar]

- August GJ, Piehler TF, Bloomquist ML. Being “SMART” about adolescent conduct problems prevention: Executing a SMART pilot study in a juvenile diversion agency. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014:1–15. doi: 10.1080/15374416.945212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- August GJ, Realmuto GR, Winters KA, Hektner JM. Prevention of adolescent drug abuse: Targeting high risk children with a multifaceted intervention model-The Early Risers “Skills for Success” Program. Applied and Preventive Psychology. 2001;10:135–154. [Google Scholar]

- Barrish HH, Saunders M, Wolf MM. Good behavior game: Effects of individual contingencies for group consequences on disruptive behavior in a classroom. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1969;2:119–124. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1969.2-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley R, Doolittle J, Bartolotta R. Building on the data and adding to the discussion: The experiences and outcomes of students with emotional disturbance. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2008;17:4–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cash RE, Nealis LK. Mental health in the schools: It’s a matter of public policy; Paper presented at the National Associaiton of School Psychologists Public Policy Institute; Washigngton, D.C.. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Child and Family Center. FCU Caregiver Questionnaire: Adolescence (11–17) Eugene: University of Oregon; 2013a. Available from http://fcu.cfc.uoregon.edu. [Google Scholar]

- Child and Family Center. FCU Youth Questionnaire: Adolescence (11–17) Eugene: University of Oregon; 2013b. Available from http://fcu.cfc.uoregon.edu. [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, Weisz JR. Modularity in the design and application of therapeutic interventions. Applied and Preventive Psychology. 2005;11:141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Weisz JR. Modular approach to therapy for children with anxiety, depression, trauma, or conduct problems. (MATCH-ADTC) Satellite Beach, FL: PracticeWise; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Murphy SA, Bierman KL. A conceptual framework for adaptive preventive interventions. Prevention Science. 2004;5(3):185–196. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000037641.26017.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Initial impact of the Fast Track Prevention Trial for Conduct Problems: I. The high-risk sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:631–647. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor CM, Piasta SB, Fishman B, Glasney S, Schatschneider C, Crowe E, Morrison FJ. Individualizing Student Instruction Precisely: Effects of Child by Instruction Interactions on First Graders’ Literacy Development. Child Development. 2009;80:77–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01247.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crone D, Hawken L, Horner R. Responding to problem behavior in schools: The behavior education program. 2nd. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Crone DA, Horner RH, Hawken L. Responding to problem behavior in schools: The education program. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Domitrovich CE, Bradshaw CP, Greenberg MT, Embry D, Poduska JM, Ialongo NS. Integrated models of school‐based prevention: Logic and theory. Psychology in the Schools. 2010;47:71–88. doi: 10.1002/pits.20452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Dishion TJ, Lansford JE. Deviant peer influences in programs for youth: Problems and solutions. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Stormshak EA, Kavanagh K. Everyday Parenting: A professional’s guide to building family management skills. Champaign, IL: Research Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Embry DD. The Good Behavior Game: A best practice candidate as a universal behavioral vaccine. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2002;5:273–297. doi: 10.1023/a:1020977107086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano GA, Pelham WE, Jr, Waschbusch DA, Gnagy EM, Lahey BB, Chronis AM, Burrows-MacLean L. A practical measure of impairment: psychometric properties of the impairment rating scale in samples of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and two school-based samples. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:369–385. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3503_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filter K, McKenna M, Benedict E, Horner R, Todd A, Watson J. Check in/Check out: A Post-Hoc Evaluation of an Efficient, Secondary-Level Targeted Intervention for Reducing Problem Behaviors in Schools. Education and Treatment of Children. 2007;30:69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JM, Vaughn S. Response to intervention: Preventing and remediating academic difficulties. Child Development Perspectives. 2009;3:30–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2008.00072.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flett GL, Hewitt PL. Disguised distress in children and adolescents “flying under the radar”. Canadian Journal of School Psychology. 2013;28:12–27. [Google Scholar]

- Forman SG, Shapiro ES, Codding RS, Gonzales JE, Reddy LA, Rosenfield SA, Stoiber KC. Implementation science and school psychology. School Psychology Quarterly. 2013;28:77. doi: 10.1037/spq0000019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster S, Rollefson M, Doksum T, Noonan D, Robinson G, Teich J. School mental health services in the United States 2002–2003. Rockville, MD: Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2005. (DHHS Pub. No. (SMA) 05-4068). [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs D, Fuchs LS. Introduction to response to intervention: What, why and how valid is it? Reading Research Quarterly. 2006;41:93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology ad Psychiatry. 1997;38:581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. Psychometic properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Journal of the American Academcy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:1337–1345. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman AD, Brown TR, Edwards KR, Krupp LB, Schapiro RT, Cohen R, Blight AR. A phase 3 trial of extended release oral dalfampridine in multiple sclerosis. Annals of Neurology. 2010;68:494–502. doi: 10.1002/ana.22240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, Kusche CA, Cook ET, Quamma JP. Promoting emotional competence in school-aged children: The effects of the PATHS curriculum. Development and psychopathology. 1995;7:117–136. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood CR, Horner RH, Kratochwill TR. Introduction. In: Greenwood CR, Krochwill TR, Clements M, editors. Schoolwide prevention models. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gresham MT. Rsponse to intervention: An alternative means of identifying students as emotionally disturbed. Education and Treatment in Children. 2005;28:328–344. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra NG, Williams KR, Tolan PH, Modeski Kl. Theoretical and research advances in understanding the causes of juvenile offending. In: Hoge RD, Guerra NG, Boxer P, editors. Treating the profile offender. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 33–53. [Google Scholar]

- Gunlicks-Stoessel M, Mufson L, Westervelt A, Almirall D, Murphy S. A pilot SMART for developing an adaptive treatment strategy for adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2016;45(4):480–494. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2015.1015133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawken LS, MacLeod KS, Rawlings L. Effects of the behavior education program (BEP) on office discipline referrals of elementary school students. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2007;9(2):94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Hawken LS, Vincent CG, Schumann J. Response to intervention for social behavior: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2008;16:213–225. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges K. Child and Adoelscent Functional Assessment Scale (CAFAS) Ypsilanti: Eastern Michigan University; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen CD, Cushing CC, Aylward BS, Craig JT, Sorell DM, Steele RG. Effectiveness of motivational interviewing interventions for adolescent substance use behavior change: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:433. doi: 10.1037/a0023992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam CM, Greenberg MT, Kusche CA. Sustained effects of the PATHS curriculum on the social and psychological adjustment of children in special education. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2004;12:66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C, Kaiser A, Goods K, Nietfeld J, Mathy P, Landa R, Almirall D. Communication interventions for minimally verbal children with autism: A Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized Trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;53(6):635–646. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Problem-solving skills training and parent management training for oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder. In: Weisz RJ, Kazdin AE, editors. Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents. 2nd. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010. pp. 211–226P. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Wassell G. Barriers to participation and therapeutic change among children referred for conduct disorder. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:160–172. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2802_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG, Brown CH, Poduska JM, Ialongo NS, Wang W, Toyinbo P, Wilcox HC. Effects of a universal classroom behavior management program in first and second grades on young adult behavioral, psychiatric, and social outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;95:S5–S28. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG, Rebok GW, Ialongo N, Mayer LS. The course and malleability of aggressive behavior from early first grade into middle school: Results of a developmental epidemiologically‐based preventive trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1994;35:259–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG, Werthamer-Larsson L, Dolan LJ, Brown CH, Mayer LS, Rebok GW, Wheeler L. Developmental epidemiologically based preventive trials: Baseline modeling of early target behaviors and depressive symptoms. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1991;19:563–584. doi: 10.1007/BF00937992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krantzler HR, McKay JR. Personalized treatment of alcohol dependence. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2012;14:486–493. doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0296-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratochwill TR, Bergan JR. Behavioral consultation in applied settings: An individual guide. New York: Plenum Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kusche CA, Greenberg MT. The PATHS (Promoting alternative thinking strategies) curriculum. South Deerfield, MA: Channing-Bete; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lane KL, Capizzi AM, Fisher MH, Ennis RP. Secondary prevention efforts at the middle school level: An application of the behavior education program. Education and Treatment of Children. 2012;35:51–90. [Google Scholar]

- Langley AK, Nadeem E, Kataoka SH, Stein BD, Jaycox LH. Evidence-based mental health programs in schools: Barriers and facilitators of successful implementation. School Mental Health. 2010;2:105–113. doi: 10.1007/s12310-010-9038-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavori PW, Dawson R, Rush AJ. Flexible treatment strategies in chronic disease: clinical and research implications. Biological Psychiatry. 2000;48:605–614. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00946-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavori PW, Dawson R. Adaptive treatment strategies in chronic disease. American Review of Medicine. 2008;59:443–453. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.59.062606.122232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei H, Nahum-Shani K, Lynch K, Oslin D, Murphy SA. A “SMART” design for building individualized treatment sequences. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2012;8:21–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Wells KC. The Coping Power Program at the middle school transition: Universal and indicated prevention effects. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16:40–54. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.16.4s.s40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh K, Campbell AL, Carter DR, Zumbo BD. Concurrent validity of office discipline referrals and cut points used in schoolwide Positive Behavior Support. Behavioral Disorders. 2009;34:100–113. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh K, Campbell AL, Carter DR, Dickey CR. Differential effects of a tier two behavior intervention based on function of problem behavior. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2009;11(2):82–93. doi: 10.1177/1098300708319127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Life-course-persistent and adolescent-limited antisocial behavior. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology. Vol. 3. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 570–598. (Risk, disorder, and adaptation). [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SA, Lynch KG, Oslin D, McKay JR, TenHave T. Developing adaptive treatment strategies in substance abuse research. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88(Supplement 2):S24–S30. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SA, Oslin DW, Rush AJ, Zhu J. Methodological challenges in constructing effective treatment sequences for chronic psychiatric disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:257–262. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens JS, Lyon AR, Brandt NE, Warner CM, Nadeem E, Spiel C, Wagner M. Implementation Science in School Mental Health: Key Constructs in a Developing Research Agenda. School Mental Health. 2014;6(2):99–111. doi: 10.1007/s12310-013-9115-3. http://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-013-9115-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick S, Marsh R. Juvenile diversion: Results of a 3-year experimental study. Criminal Justice Policy Review. 2005;16:59–73. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, DeBaryshe BD, Ramsey E. A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. American Psychologist. 1989;44:329–344. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.2.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Jr, Fabiano GA, Massetti GM. Evidence-based assessment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:449–476. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3403_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Fabiano GA, Waxmonsky JG, Greiner AR, Gnagy EM, Karch K. Treatment sequencing for childhood ADHD: A multiple-randomization study of adaptive medication and behavioral interventions. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2016:1–20. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2015.1105138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poduska JM, Kellam SG, Wang W, Brown CH, Ialongo NS, Toyinbo P. Impact of the Good Behavior Game, a universal classroom-based behavior intervention, on young adult service use for problems with emotions, behavior, or drugs or alcohol. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;95:S29–S44. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Kamphaus RW. Behavioral Assessment System for Children 2nd Edition: Manual. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Services; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rones M, Hoagwood K. School-based mental health services: A research review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2000;3:223–241. doi: 10.1023/a:1026425104386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortreed SM, Moodie EEM. Estimating the optimal dynamic antipsychotic treatment regime: evidence from the sequential multiple-assignment randomized Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention and Effectiveness schizophrenia study. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series C (Applied Statistics) 2012;61:577–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9876.2012.01041.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]