Abstract

Spur cell haemolytic anaemia (SCA) is a form of anaemia that can be seen in patients with severely impaired liver function or advanced cirrhosis. It is associated with high mortality. The treatment options for SCA secondary to cirrhosis are limited. Our patient is a middle-aged man who developed SCA and was not a candidate for liver transplantation or splenectomy. High-dose steroids helped ameliorate haemolysis and improve anaemia and general condition of our patient.

Keywords: cirrhosis, non-alcoholic steatosis, haematology (drugs and medicines), medical management, therapeutic indications

Background

Anaemia in liver disease may be due to anaemia of chronic disease, nutritional deficiencies, gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding or haemolysis. The latter may be due to hypersplenism or acquired alteration of the red cell membrane.1 Lipid alteration in red cell membrane in liver disease can give rise to different morphological changes such as target cells, acanthocytes, echinocytes and keratocytes.2 Here we describe a case of severe spur cell haemolytic anaemia (SCA) which responded to steroid therapy.

Case presentation

A 66-year-old African-American man with medical history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-induced cirrhotic portal hypertension (Child-Pugh score 10), with history of bleeding from grade IV oesophageal varices 2 weeks earlier, controlled by banding, with stable haemoglobin and haematocrit as outpatient (around 7.5 g/dL), was admitted to intensive care unit (ICU) with dizziness. Vital signs revealed temperature of 96.8 F, blood pressure of 90/50 mm Hg, heart rate of 110/min and respiratory rate of 22/min. Digital rectal examination was negative for gross blood or melena.

Investigations

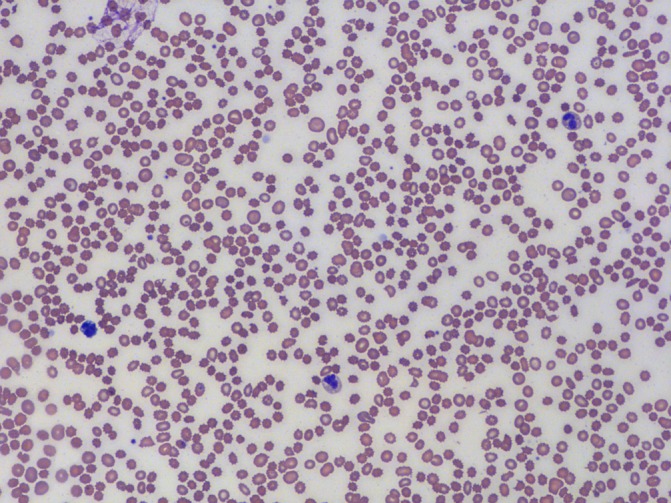

Haemoglobin had dropped from 7.1 g/dL to 6.6 g/dL, without overt GI bleeding symptoms such as hematemesis or change in colour of stools. Other laboratory tests: red cell MCV 94 fL, stable white cell 3.7x10^9/L platelet count 33x10^9/L (same as baseline), elevated serum bilirubin 6.2 mg/dL, indirect 5.7 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase 82 U/L (normal 10–37 U/L), normal alanine aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase, normal activated partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time 18 s (international normalised ratio 1.5), fibrinogen 465 mg/dL, haptoglobulin <7.75 mg/dL (normal 30–200 mg/dL), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 1104 U/L (normal 84–246 U/L) and reticulocyte count 5.2%. A peripheral smear revealed almost 90% acanthocytes and some target cells (figure 1). Haemolytic anaemia work-up revealed: negative paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria by flow cytometry, normal haemoglobin electrophoresis, no abnormal variants or thalassemia detected by protein analysis methods, normal haemoglobin stability studies, negative DNA sequence analysis for alpha-1 globin gene, alpha-2 globin gene and beta globin gene mutation, an unstable haemoglobin or other types of hemoglobinopathy. Osmotic fragility and eosin-5-maleimide binding tests were negative for hereditary spherocytosis or pyropoikilocytosis. Red cell glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, pyruvate kinase, hexokinase and glucose phosphate isomerase enzyme levels were normal or elevated. Direct Coombs test, urine haemosiderin, antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, C3/C4, hepatitis B and C screen and serum and urine protein electrophoresis were negative.

Figure 1.

Peripheral smear revealed numerous acanthocytes.

Ongoing haemolysis led to further rise in serum LDH and indirect bilirubin as shown in table 1. In the interim, patient also became severely oliguric with rising serum creatinine, resulting from hypotensive period at the time of ICU admission.

Table 1.

Trend of laboratory values in our patient before and after steroid administration

| Laboratory | Day 1 | Day 3*** | Day 5 | Day 7 | Day 9 | Day 11 |

| Haemoglobin/haematocrit | 6.6/21 | 5.2/16.4 | 6.6/20 | 8.4/26.2 | 8.3/26.2 | 8.6/27.3 |

| Haptoglobin | <7.75 | <7.75 | <7.75 | <7.75 | 21.1 | 33.6 |

| Reticulocyte count | 5.2 | 7.7 | 8.2 | 7.64 | 2.5 | 2.3 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 1495 | 1864 | 1343 | 947 | 733 | 504 |

| Total bilirubin/indirect | 9.7/8.5 | 11.2/8.9 | 4.5/2.2 | 2.0/1.0 | 1.6/0.6 | 1/0.4 |

***Day of steroid administration

Treatment

Acute SCA secondary to advanced liver disease was diagnosed, and patient was started on high-dose steroids, methylprednisolone 125 mg intravenously four times per day for 24 hours, followed by 125 mg intravenous per day for 6 days. After initiation of steroids, patient’s haemoglobin increased with improvement in other laboratory parameters of haemolysis (table 1). Peripheral blood smear revealed only an occasional acanthocyte (figure 2). For acute renal failure, patient was placed on haemodialysis temporarily until serum creatinine and oliguria improved.

Figure 2.

Peripheral smear after steroid administration revealed scant acanthocytes.

Outcome and follow-up

Two days after initiation of steroids, patient’s haemoglobin improved to 6.6 g/dL and stabilised around 8.4 g/dL. Patient was then switched to oral prednisone 60 mg per day the next day (after 7 days of intravenous steroids) and eventually discharged home on prednisone 20 mg per day.

Discussion

Our patient was moderately anaemic as outpatient because of chronic liver disease and recent GI blood loss. However, anaemia suddenly worsened in the absence of active GI bleeding. Haemoglobin dropped to 5.2 g/dL with rising indirect hyperbilirubinaemia and serum LDH, very low serum haptoglobin, reticulocytosis, negative direct Coombs test and blood smear revealing 80%–90% acanthocytes. Despite daily blood transfusions, haemoglobin remained low around 6 g/dL. Introduction of high-dose steroids not only stabilised haemoglobin but also improved haemoglobin to 8.6 g/dL. Serum LDH, haptoglobin and reticulocytosis, along with indirect hyperbilirubinaemia, improved, and the patient was discharged on a small dose of oral prednisone. Blood smear disclosed almost complete disappearance of acanthocytes from 80%–90% to 1%–2%.

Therapeutic options for treatment of SCA are limited. Liver transplantation or splenectomy may lead to amelioration of spur cells and subsequently anaemia, though none of these options are easy to implement.3 4 Liver transplantation has strict criteria, and rarely patients qualify. Operative morbidity of splenectomy is not trivial due to underlying risk factors such as alcoholism, malnutrition, thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy and intolerance to anaesthesia.5 Steroids may be considered as a possible therapeutic management; as a less invasive option in such critically ill patients. It was quite gratifying that after stabilisation of haemoglobin, our patient was successfully discharged.

Acanthocytes (from the Greek word ‘acantha’ meaning thorn) or spur cells appear dense, contracted and irregular, with spiculated projections which vary in size and distribution.6 Severe liver disease is one of the many causes of SCA. Other causes include myxedema secondary to hypothyroidism, abetalipoproteinaemia, neuroacanthocytosis, McLeod blood type, anorexia nervosa and other malnutrition states.7 8

The molecular mechanisms of occurrence of SCA are not completely understood and may include influence on distribution and proportion of red membrane lipids and proteins. Severe liver dysfunction causes production of an abnormal apolipoprotein A-II deficient lipoprotein. This abnormal lipoprotein loads red cells with cholesterol, causing an increased cholesterol to phospholipid ratio and an increased surface area, commonly within the outer layer.9

Cholesterol laden red cells are then remodelled in the spleen, resulting in the typical spur cell shape. An increase in red blood cell (RBC) membrane proteolytic activity also contributes to spur cell formation. The resulting spur cells are less deformable, hence are easily trapped in the spleen and hemolyzed.10 Recent studies have shown that in patients with spur cell, there is an increase in the ratio of free (or unesterified) cholesterol relative to phospholipid in both serum and red cells. A strong correlation exists between cholesterol to phospholipid disproportion in red cell membrane and plasma. The spur cells are acquired by normal red cells infused in patients with spur cells, hence serum lipoprotein abnormality or plasma factor is aetiological in cases of SCA. Hence to summarise, spur cells occur by a combination of increased cholesterol in RBC membrane, which is characteristic of liver disease, defective surface area to volume ratio, impaired membrane fluidity and inability to remove perioxidatively damaged fatty acids in RBC membrane.11 12

The exact mechanism by which steroid administration helped stabilise anaemia in our patient is unknown. One possible mechanism is the introduction of oxygenated derivatives of cholesterol into RBC membranes, causing membrane expansion, as proposed by Streuli et al and Ballin et al. In an isotonic environment, there was no effect on haemolysis. But in a hypotonic environment, the increased cell to surface to volume ratio stabilised RBCs and helped decrease haemolysis. The studies were performed in children with hereditary spherocytosis,13 14 whether a similar mechanism is involved in patients with SCA is unproven.

In a study performed by Moreno et al, the interaction of naturally occurring steroid with red cell membrane has been assessed. Steroids have been postulated to interact with phospholipid classes present in erythrocyte membranes, especially dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine (DMPC). Steroid causes gradual hydration of DMPC, resulting in water accumulation in the RBC membrane and increasing width, which further may prevent haemolysis.15 The interaction of steroids with phospholipids is further affirmed by Bangham et al. They also suggest that steroids alter permeability of RBC membrane.16 Hence, in our patient, steroids may have helped ameliorate haemolysis by either increasing oxygenated cholesterol in red cell membrane or interacting with phospholipids causing water accumulation in RBC membrane which helped stabilise RBC and prevent haemolysis or by directly stimulating erythropoiesis or by an effect on splenic remodelling. Exact mechanism remains unclear and unproven.

A possible mechanism for improvement of anaemia itself but not haemolysis is stimulation of erythropoiesis by steroids as suggested by Duru and Gürgey.17 In their study, corticosteroids were administered to three children with hereditary spherocytosis and severe haemolytic anaemia. Anaemia improved, and reticulocyte count increased in all three patients.17

Acanthocytosis due to severe liver dysfunction is a hallmark of high risk of mortality. A prospective study by Alexopoulou et al indicated that in patients with liver cirrhosis and spur cell anaemia, higher mortality has been reported compared with cirrhotic without spur cell anaemia. The study which included 116 patients with cirrhosis reported survival rates of 77%, 45% and 33%, in patients with spur cell anaemia, at 1-month, 2-month and 3-month follow-up, respectively.18 As life span of these patients is short, the question of long-term toxicity of steroids may not be of overwhelming concern. The improvement in quality of life by decreasing the need for recurrent blood transfusions may be of greatest benefit.

Learning points.

Spur cell haemolytic anaemia can be associated with advanced liver disease, hypothyroidism, abetalipoproteinaemia, neuroacanthocytosis and other malnutrition states.

Occurrence of SCA indicates poor prognosis in patients with advanced liver cirrhosis.

Liver transplantation or splenectomy is a treatment option for patients with cirrhosis with SCA.

In patients who are not surgical candidates, steroids may be a viable option to mitigate haemolysis and anaemia.

Footnotes

Contributors: DK was involved in the care of the patient and eventually wrote the initial manuscript. SS was the pathologist involved in the case and helped obtain images for the case report. PP helped collect references and reviewed the discussion part. BA was involved in the final correction and review of the manuscript. All authors have reviewed the final version of the manuscript and agreed with its conclusions.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Gonzalez-Casas R, Jones EA, Moreno-Otero R. Spectrum of anemia associated with chronic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:4653 10.3748/wjg.15.4653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zieve L. Hemolytic anemia in liver disease. Medicine 1966;45:497–505. 10.1097/00005792-196645060-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malik P, Bogetti D, Sileri P, et al. Spur cell anemia in alcoholic cirrhosis: cure by orthotopic liver transplantation and recurrence after liver graft failure. Int Surg 2002;87:201–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dhaliwal G, Cornett PA, Tierney LM. Hemolytic anemia. Am Fam Physician 2004;69:2599–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tabbara IA. Hemolytic anemias. Diagnosis and management. Med Clin North Am 1992;76:649–68. 10.1016/S0025-7125(16)30345-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith JA, Lonergan ET, Sterling K. spur-cell anemia: hemolytic anemia with red cells resembling acanthocytes in alcoholic cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 1964;271:396–8. 10.1056/NEJM196408202710804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker RH, Jung HH, Dobson-Stone C, et al. Neurologic phenotypes associated with acanthocytosis. Neurology 2007;68:92–8. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000250356.78092.cc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kay J, Stricker RB. Hematologic and immunologic abnormalities in anorexia nervosa. South Med J 1983;76:1008–10. 10.1097/00007611-198308000-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper RA, Diloy Puray M, Lando P, et al. An analysis of lipoproteins, bile acids, and red cell membranes associated with target cells and spur cells in patients with liver disease. J Clin Invest 1972;51:3182–92. 10.1172/JCI107145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper RA, Kimball DB, Durocher JR. Role of the spleen in membrane conditioning and hemolysis of spur cells in liver disease. N Engl J Med 1974;290:1279–84. 10.1056/NEJM197406062902303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen DW, Manning N. Cholesterol-loading of membranes of normal erythrocytes inhibits phospholipid repair and arachidonoyl-CoA:1-palmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine acyl transferase. A model of spur cell anemia. Blood 1996;87:3489–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen DW, Manning N. Abnormal phospholipid metabolism in spur cell anemia: decreased fatty acid incorporation into phosphatidylethanolamine and increased incorporation into acylcarnitine in spur cell anemia erythrocytes. Blood 1994;84:1283–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Streuli RA, Kanofsky JR, Gunn RB, et al. Diminished osmotic fragility of human erythrocytes following the membrane insertion of oxygenated sterol compounds. Blood 1981;58:317–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ballin A, Waisbourd-Zinman O, Saab H, et al. Steroid therapy may be effective in augmenting hemoglobin levels during hemolytic crises in children with hereditary spherocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2011;57:303–5. 10.1002/pbc.22844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manrique-Moreno M, Londoño-Londoño J, Jemioła-Rzemińska M, et al. Structural effects of the Solanum steroids solasodine, diosgenin and solanine on human erythrocytes and molecular models of eukaryotic membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014;1838:266–77. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bangham AD, Standish MM, Weissmann G. The action of steroids and streptolysin S on the permeability of phospholipid structures to cations. J Mol Biol 1965;13:253–IN28. 10.1016/S0022-2836(65)80094-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duru F, Gürgey A. Effect of corticosteroids in hereditary spherocytosis. Acta Paediatr Jpn 1994;36:666–8. 10.1111/j.1442-200X.1994.tb03266.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alexopoulou A, Vasilieva L, Kanellopoulou T, et al. Presence of spur cells as a highly predictive factor of mortality in patients with cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;29:830–4. 10.1111/jgh.12473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]