Abstract

The cancer burden is rising globally, exerting significant strain on populations and health systems at all income levels. In May 2017, world governments made a commitment to further invest in cancer control as a public health priority, passing the World Health Assembly Resolution 70.12 on cancer prevention and control within an integrated approach. In this manuscript, the 2016 European Society for Medical Oncology Leadership Generation Programme participants propose a strategic framework that is in line with the 2017 WHO Cancer Resolution and consistent with the principle of universal health coverage, which ensures access to optimal cancer care for all people because health is a basic human right. The time for action is now to reduce barriers and provide the highest possible quality cancer care to everyone regardless of circumstance, precondition or geographic location. The national actions and the policy recommendations in this paper set forth the vision of its authors for the future of global cancer control at the national level, where the WHO Cancer Resolution must be implemented if we are to reduce the cancer burden, avoid unnecessary suffering and save as many lives as possible.

Keywords: global cancer control, cancer treatment inequalities, global cancer burden

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Global cancer control has been a growing priority of governments globally and the World Health Organisation (WHO) as reflected in numerous guidance documents and commitments. WHO and International Agency for Research on Cancer have produced technical guides for the development and implementation of cancer prevention and control activities ranging from identifying carcinogens to access to essential medicines and palliative care. Additionally, countries and WHO have made commitments to global cancer control such as the 2013–2020 WHO Global Action Plan on the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases, the 2030 UN Agenda for Sustainable Development and most importantly the 2017 World Health Assembly (WHA) Resolution on Cancer prevention and control within an integrated approach. The guiding principles of these WHO and UN documents is that health is a basic human right, and in order to respect that right, health services need to be provided through a universal health coverage system that leaves no one behind.

What does this study add?

This paper looks at the 2017 World Health Assembly Resolution on Cancer prevention and control within an integrated approach from a public policy perspective. It reflects the vision of the European Society for Medical Oncology’s future oncology leaders on the resolution’s implementation at the national level. It addresses the key topics of the Cancer Resolution like cancer prevention, timely access to treatment and care, palliative and survivorship care, and comprehensive data collection through robust cancer registries. It provides a set of concrete actions and policy recommendations to improve patient care. This study is the first to articulate the response and commitment of leading experts in cancer to advance global cancer control through the framework of the 2017 WHA Cancer Resolution and universal health coverage.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Public policy has a tremendous effect on the profession and practice of medical oncology. National health systems are created through public health policies. The way that health systems are structured, the services that they offer, the competencies and training requirements of their workforce, the quality standards of their treatment of patients, and the robustness of cancer registry data are all public policy issues aimed at improving patient outcomes. The global policy recommendations set out in this paper can harmonise efforts across the globe to address critical issues in cancer management with sustainable solutions.

Introduction

Historically, cancer has received alarmingly little attention from global policymakers and donors in spite of the significant and increasing health burden. Approximately 8.8 million people are dying each year of cancer, amounting to one out of six deaths globally and far exceeding the number of deaths from HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis combined.1 The disease burden is greatest in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs), where 75% of cancer deaths occur and the number of cancer cases is rising most rapidly.

Importantly, cancer incidence is estimated to double by 2035.2 The greatest increase in cancer cases is expected in LMICs due to demographic changes, such as ageing of the population, and increasing exposure to risk factors. However, health systems, particularly those in LMICs, are not well prepared or equipped to manage this growing burden, and current budgetary allocation and global resource mobilisation are markedly insufficient. While an estimated 60% of cancer cases occur in LMICs, only 5% of global spending on cancer is directed to these countries.3 Furthermore, only 1% of global health financing is directed to non-communicable diseases (NCDs), which include cancer, and is vastly disproportionate to the actual NCD burden.4 The growth in oncology cost is expected to rise 7%–10% annually throughout 2020, when global oncology costs will exceed $150 billion.5

The consequence has been significant physical, financial and emotional strain on individuals and families suffering from cancer around the globe. Prolonged disability and premature mortality have a substantial economic impact. The high direct and indirect economic costs of cancer need particular considerations, and a substantial portion of cancer patients are not accessing or receiving adequate care mainly because of weak health systems, inadequate national services, disparities in access to cancer care and high financial costs. In addition, there is a lack of public information and awareness on how to recognise the signs that a person has cancer. This delays timely access to care, resulting in late-stage cancer diagnoses and premature cancer mortality.

The World Health Assembly (WHA) is the governing body of WHO, and it meets every year in May in Geneva. At last year’s 70th WHA, 194 governments from around the world came together and resoundingly passed the Resolution Agenda Item 15.6 (WHA70.12), known as the ‘Cancer Resolution’. The resolution states in no uncertain terms that cancer prevention and control is a significant and growing public health concern requiring attention, investment and prioritisation by governments and international organisations at the national and global level.6 This Cancer Resolution is a milestone achievement because until now cancer has not been either high or visible on the global health agenda. Therefore, we must harness this opportunity and act through united global, national and local efforts to assure its implementation. One of the resolution’s main goals is timely access to cancer treatment and care for all, upholding the 1948 United Nations Universal Declaration on Human Rights, which states that everyone has the basic right to medical care to assure the health and well-being of themselves and their families.7

Addressing the growing cancer burden as a public health priority is challenging. Cancer is a not a single disease but rather a multitude of diseases. Many cancers are heterogenous in their characteristics, with hundreds of histological and biological subtypes. It requires specific diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, and a qualified workforce to implement them, coupled with the imperative need of coordinated multidisciplinary patient care. Additionally, while cancer programmes can build on the progress made within the global NCD agenda, there are specificities in cancer prevention and control that require particular attention. For example, cancer is not only an NCD, but also a ‘communicable’ disease. Up to 25% of cancers in LMICs can be attributed to communicable diseases such as hepatitis B and C (hepatocellular carcinoma), human papilloma virus (HPV) (cervical cancer) and parasitic infections, such as liver flukes and schistosomiasis (biliary and bladder cancers).8 To address hepatitis B and HPV through the implementation of nationwide vaccination programmes requires synergies across disciplines.

Strategies to address the global cancer burden must be tailored to the local reality. It must account for a country’s most prevalent cancer types and be tackled according to the country’s available resources. To properly allocate resources, accurate comprehensive cancer registries are essential to provide information on the epidemiology of cancer in the country. Decisions must be based on the best available evidence and accurate epidemiological data, addressed within a national cancer control plan (NCCP). While >70% of countries have NCCPs, not all of them are well funded and implemented.9 The successful implementation of any NCCP requires involvement of all stakeholders, including health policymakers, academic organisations, healthcare professionals, civil society, patients, industry and the media because the status quo is not working.

Need for action

Change is needed, and the United Nations’ ‘2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’ has defined the target. Goal 3 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) seeks to ensure healthy lives and to promote well-being for all people at all ages. Two particular targets within SDG number 3 relate to cancer: (1) the reduction in premature mortality from NCDs, including cancer, by one-third by 2030; and (2) achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential healthcare services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.10

This paper articulates the vision of the participants of the 2016 European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Leaders Generation Programme11 to address the challenges facing cancer care globally. We aim to propose a strategic framework at the national level to achieve effective cancer care for all, based on the concept of universal health coverage and the commitments made by 194 countries to implement the 2017 WHO ‘Cancer Resolution’. At the end of each section of the paper, we provide national policy recommendations that are in line with our vision, ESMO initiatives, and the 2017 WHO Cancer Resolution. Our vision is supported by the ESMO leadership and the ESMO Public Policy Steering Committee.

The ESMO Leaders Generation Programme was launched in 2016 and gathered outstanding early career oncologists from all over Europe. This programme is designed to train the next generation of oncology leaders to take on the responsibility of advancing the practice and profession of medical oncology worldwide with the goal of improving access to high-quality cancer care for everyone everywhere. In table 1 we identity examples of key strategic priority actions at the national level for policymakers, health planners, clinicians, patients and civil society to achieve the goal of equal access to cancer care worldwide. This needs to be a priority for the future of oncology, and we need to advocate for it - for our patients at home and for patients in clinics across the world. We understand that global cancer policies are essential; however, they will only be successful if they are implemented within each country at the national, regional and local levels.

Table 1.

Summary of priority actions of key national stakeholders in cancer control to reduce inequalities in access to cancer care

| Stakeholder group | Sample national priority actions |

| National policymakers |

|

| Regional or facility health planners |

|

| Academic societies |

|

| Clinicians/providers |

|

| Patients and civil society |

|

Developing a framework for action

Inequities in cancer care are widespread between and within countries, and health systems must be reoriented around the patients and their needs to improve cancer outcomes for all. Up to 50% of all premature deaths from NCDs, including cancer, have been associated with inadequate health systems that do not respond effectively and equitably to healthcare needs of the population.12

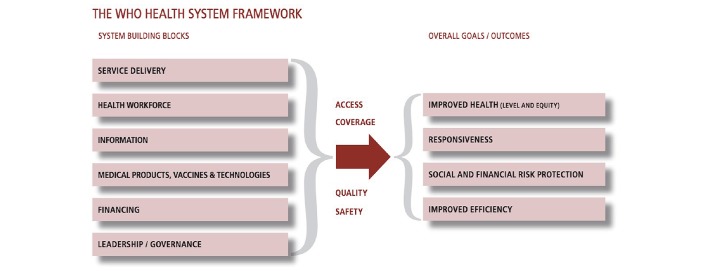

Therefore, a significant proportion of cancer-related deaths can be avoided if action is taken and an adequate restructuring of health systems is implemented. This will require training in the organisation of cancer services and how to deliver them effectively and efficiently with a country’s available human and financial resources. It will also require strengthening of health information systems along with a political commitment to timely patient access to essential cancer services. WHO’s six building blocks and overall goals for health systems are reported in figure 1.

Figure 1.

The six building blocks of a health system that must be considered for effective, comprehensive delivery of cancer services. Taken from: Everybody’s business—strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes.55

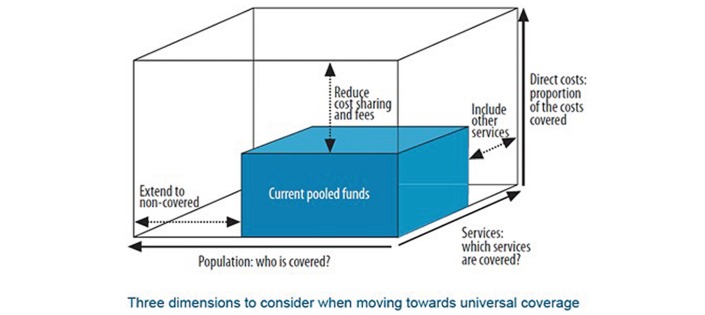

To have a measurable impact on the lives of cancer patients, an approach is needed that links public health policies to clinical outcomes. Oncologists are well positioned as leaders in delivering clinical cancer services. They can provide valuable input to guide public health strategies and work with policymakers to develop and implement a robust health systems framework. Access to quality cancer care should be based on the three WHO principles of universal health coverage outlined in figure 2, which are (1) reduce direct costs, (2) improve population coverage and (3) promote service coverage.

Figure 2.

Three dimensions to consider when moving towards universal coverage.56

Dimension 1: address the financial burden of cancer diagnosis and treatment (direct costs)

The high direct and indirect economic cost of cancer needs particular attention because a substantial portion of patients with cancer are not accessing or receiving adequate care because of its financial burden. There are considerable variations in access to, and financing of, cancer care across different countries, with differences in public contributions (eg, government agencies and donors) and household ‘out-of-pocket’ expenses. LMICs are particularly vulnerable as only about 5% of global cancer funds are directed towards those countries, placing a significantly greater burden on individual patients and households.13

The reasons that low proportions of total cancer costs are covered by public contributions are multifactorial. First, a significant gap exists between the health spending of developed and less developed countries. For example, in the financial year 2015–2016, 145 billion British pounds were allocated to health services in the UK (18.7% of total governmental budget).14 In less developed countries, or fragile states, government budgets are already limited, and resources are spent on competing public needs such as education or security. Therefore, healthcare costs are covered by out-of-pocket expenditure by the patients. In some war-torn countries, government expenditure on health is <1% of the budget allocated for security.15 16 Therefore, out-of-pocket expenditures represent a significant percentage of total health expenditure—an estimated 37%–50% of total health expenditure in low-income and lower-middle-income countries.17 Second, prices may partially explain the differences in availability of cancer medicines and disparity in cancer care.18 In a recent study, despite generally lower prices of medicines in less developed countries, medicines were less affordable because of lower income per capita.19 Per capita expenditure on health (purchasing power parity) is $92 in low-income countries compared with $5205 in high-income countries.17

To overcome high direct costs that function as a barrier to universal cancer care, a multisectoral strategy is required. We need to raise awareness that cancer is not a death sentence, and that cancer treatment can be implemented in a cost-effective manner. We need to foster this recognition in governments—in both the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Health, as well as in the general public. Current pooled funds (figure 2, blue box) should be directed towards priority ‘best buys’ in cancer control, which are cancer interventions that are cost-effective.20 Cancer control programmes should be selected recognising the infrastructure facilities required for their effective delivery. For example, breast cancer screening should not be prioritised until there is adequate health system capacity to treat the diagnosed cases—including trained pathologists and radiologists.21

Generally, WHO estimates that between 20% an 40% of health expenditure is wasted.22 By reducing low-impact, high-cost expenditures in cancer care, resources can be reallocated to a package of essential cancer services at low cost. By identifying and resolving inefficiencies and unnecessary expenditures—for example, performing a positive emission tomography scan on a cancer patient with early-stage disease—financial resources can be redirected for necessary diagnostic and treatment expenditures.

Recommendations

- Prioritise efficient use of national resources

- Invest in cancer prevention

- Promote early diagnosis among public and general practitioners to identify cancer at an earlier stage when treatment is more effective and less expensive

- Pool procurement of essential medicines and devices to reduce costs

- Identify priority cancer treatment regimens that provide similar outcomes but at significantly lower costs

- Consider the use of generics and biosimilars

- Assure equity in cancer care that is sustainable, affordable and available to everyone

- Medical professionals should advocate for, and with, patients with cancer, in hospitals, in the media, and at national and global levels, for cancer care that is sustainable, affordable and available to everyone

Dimension 2: promote full population coverage by addressing geographic, financial and sociocultural barriers (population coverage)

There are two competing needs in promoting population coverage based on geographical access to cancer care. We need to reconcile the differences in services provided at centralised facilities and those provided in rural areas. The services at high-volume centralised facilities are generally more effective with better outcomes; contrasted against the decentralised services with local care, which generally facilitate accessibility of services and early diagnosis of cancer in more rural areas.23–25

Another important objective is to promote health coverage at primary and secondary levels because the vast majority of patients enter the health system at these points. Services at these levels include core interventions ranging from counselling for cancer prevention to early diagnosis and palliative care.26 In addition, where cancer screening programmes exist, participation in those programmes depends on timely access to primary care and cancer services.27 Without strong primary and secondary care services, patients with cancer will not be able to access specialised services in a timely manner, resulting in the majority of patients presenting with advanced disease.

Gaps in population coverage can arise because of differential access to insurance schemes, sociocultural factors such as age and poverty, and other barriers to access care. For example, cancer centres and advanced therapies may exist in a capital city but are not generally available for the majority of the population of a country who live in other areas. Strategies are needed to extend coverage to those who are currently unable to access care.9

In line with the 2017 WHO Cancer Resolution, ESMO is addressing the needs of specific vulnerable patient populations. For example, the treatment of elderly patients is addressed in the ESMO Handbook on Cancer in the Senior Patient 28; ESMO leads the Rare Cancers Europe29 initiative for people with rare cancers; and ESMO has a joint working group with the European Society for Pediatric Oncology for the treatment of adolescents and young adults.30

Recommendations

Adapt the organisation of cancer care to promote full population coverage

Assure comprehensive cancer services are acceptable and applicable to a country’s entire population

- Strengthen regional and subregional partnerships for cancer management and improve coordination of services as well as geographic accessibility

- Create a national network connecting rural practices to a large cancer centre which covers all regions in a country and includes pathological diagnosis as well as treatment decisions

- Cancer experts can travel as visiting physicians to less-populated areas, with general practitioners instructed on how to monitor and follow patients in between their visits

- Patient cases can be reviewed by multidisciplinary tumour boards who travel to various locations and discuss with local physicians difficult or complex cases

- Communication between urban and rural areas can take place regularly by teleconferences or online via telemedicine

- Provide for the long-term care needs for all patients with cancer including vulnerable populations

- Provide direct diagnosis and treatment infrastructure, particularly in rural regions, to assure earlier diagnosis of cancer, yielding better outcomes and higher return on investments

Assure all patients have enough insurance coverage for adequate cancer care

Dimension 3: strengthen systems to provide essential services (service coverage)

NCCPs aim to decrease incidence, increase disease cure rates, prolong life and improve patients’ quality of life by identifying priority services to be provided and covered. The most cost-effective way of reducing the cancer burden is by enhancing awareness and implementation of prevention programmes. In spite of maximal prevention efforts, >8 million people will develop cancer—investment in cancer management and treatment is therefore crucial. A critical strategy in cancer planning is to devise a stepwise approach on how to include new cancer service bundles, taking into consideration the resource availability of the local setting. For example, a first step could be to agree on national cancer bundles with centres of excellence and affiliated clinics. These bundles would serve as the foundation of a country’s initial cancer service coverage.31 32 Prerequisites for adopting new cancer services may include the development of cancer management protocols that are adapted to the national setting or competency training for healthcare providers. In addition, service coverage should be based on evidence-based guidelines and policies.

The development of NCCPs is only the first step in comprehensive cancer control. Implementation of the plan includes providing adequate financial support, information dissemination, public engagement, responsible leadership and routine monitoring and evaluation. In lower-resource settings, national cancer controls plans should prioritise high-impact packages of services—that is, those assessed as very cost-effective and essential.33 34 In addition, critical cancer services, such as pathology and palliative care, must be available before considering advanced, high-cost interventions.

Expanding the availability of essential cancer treatment packages has been shown to produce significant health and economic benefits.35–37 New innovative medicines can further contribute to increasing the cure rate and number of cancer survivors. However, these new medicines must be evaluated within the context of national budgets and the financial protection of patients. The 2013–2020 WHO Global NCD Action Plan calls for at least 80% access to essential medicines by 2025. Basic systemic therapy should be considered in cancer packages for universal health coverage. However, the majority of low-income and lower-middle-income countries do not have access to subsidised chemotherapy.9 Ensuring accessible cancer treatment generally requires that medicines are included in insurance coverage packages at the governmental level, and that those medicines are also routinely available at the facility level. Significant gaps in the access and availability of medicines, quality cancer surgery and radiotherapy can result in poor clinical outcomes for patients.38 Gaps in access to high-quality multimodality treatment result in millions of lives being lost.

Finally, universal coverage schemes are needed for palliative care because it is a vital component of comprehensive care throughout the life course, and it is consistent with the 2014 WHA Resolution 67.19 on improving access to palliative care.39 Despite widespread recognition of the importance of palliative care, an estimated 5.5 billion people have no adequate access to pain medication.40 Currently, only 41% of countries reported palliative care was available in primary healthcare, and 43% reported routine access to morphine.9 Using standards derived from WHO and the International Narcotics Control Board, ESMO performed European and global studies that demonstrated that formulary deficiencies and excessive regulatory barriers interfere with appropriate access to opioids, and therefore patient care, in many countries. To address this issue, ESMO, together with the international palliative care community, has provided countries with 10 recommendations to reduce barriers in access to opioids for legitimate scientific and medical use that can be accessed from the ESMO website.41–43

Recommendations

- Provide comprehensive, resource-appropriate and evidence-based cancer service packages

- This requires effective planning and implementation of national cancer control programmes based on epidemiological profiles. The 2017 Cancer Resolution mandates WHO to develop or adapt a plan of stepwise, and resource-stratified, guidance to define such packages, leveraging the work of other organisations such as ESMO.

- Assist health planners by providing tools to help determine the value of cancer care

- To this end ESMO has developed a tool called the ESMO Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale. This dynamic tool provides health technology assessment bodies with a resource to prioritise the reimbursement of newly licensed medicines based on their incremental clinical benefit to patients.44 45

Make accessible to all patients in the country the cancer treatment regimens included in the national clinical practice guidelines

The Cancer Resolution calls on WHO to support implementation of cost-effective interventions, harmonising and aligning the guidance provided by WHO with the clinical practice guidelines of international organisations such as ESMO46 47

- Reduce the barriers of access to cancer medicines, and as a minimum, make those on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines available and affordable to everyone

- ESMO’s European and International Anti-Neoplastic Medicines Surveys 2014–201638 48 were led by the ESMO Global Policy Committee and provided authorities with data on the actual availability of licensed antineoplastic medicines when prescribed. In many countries, especially LMICs, some cancer medicines—and even those that are on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines49—were not available and/or affordable for everyone. Following on the results of those surveys, ESMO created the Cancer Medicines Working Group to work with global stakeholders and address topics related to inexpensive, essential cancer medicines, as well as expensive, innovative cancer medicines. A key achievement of the Working Group was the publication in May 2017 of a report by the Economic Intelligence Unit and ESMO, which set out a list of six policy recommendations on how to avoid and manage cancer medicine shortages in Europe.50

- Develop cancer registries and health information systems that collect standardised data which is comprehensive and accurate, so that decision-makers can make informed and evidence-based policy decisions

- Cancer registry information on incidence and survival are necessary to determine the service capacities required of primary, secondary and tertiary health facilities. Cancer registries should exist in every country, and the data should be collected in a standardised format, both for early and advanced stages of the disease. The 2017 WHO Cancer Resolution mandates data collection to measure inequalities in cancer care in order to guide future policies and plans.

Framing: the importance of high quality

In cancer care, universal health coverage and access must be framed by quality. People living with cancer can be free of financial, geographic or coverage barriers, but if that individual receives low-quality treatment, then there is no significant value to access and universal health coverage. The six dimensions of quality as defined by WHO include that care is (1) effective (evidence-based), (2) efficient (maximises resource use), (3) accessible (timely, geographically reasonable where skills are appropriate), (4) acceptable and patient-centred (accounting for patient preferences), (5) equitable (without variation in quality because of any characteristic) and (6) safe.51 There are obstacles to these six quality dimensions for cancer diagnosis and treatment, and three key levels should be considered to improve quality: (1) policy, (2) health service provision and (3) community and service users (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Process of quality improvement, roles and responsibilities. Taken from WHO Quality of Care: A Process for Making Strategic Choices In Health Systems.51

Unfortunately, for most countries, there remains a significant gap between the demand for evidence-based data and the availability of that data, which is required to support decision-making and ensure high-quality outcomes. At the policy level, it is important that people with expertise support decision-making to establish high-quality cancer-related health programmes and consider innovative approaches and organisational structures. A strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) analysis can facilitate performance assessment and identify metrics in order to track quality over time. A comprehensive situational or SWOT analysis is the foundation for rational national cancer care programmes. Measurements should be directly linked to interventions or outcomes. Analyses and metrics should also integrate the patient perspective assessed through ‘patient-reported outcome measures’ and ‘patient-reported experience measures’. However, in addition to SWOT analyses and patient-reported information, greater community engagement and empowerment is needed in local and national policy decision-making.

High quality is also necessary at the provider level and must be a tenet for all providers in the cancer continuum, who are defined as ‘all people engaged in actions whose primary intent is to enhance health’.52 Numerous studies show evidence of a direct and positive link between the availability of health workers and population health outcomes.52 Currently, many countries lack the human resources needed to deliver basic cancer interventions. Possible underlying reasons for this include limited training capacity, migration of health workers within and across countries, a poor mix of professional skills, and demographic imbalances.

Recommendations

- Mobilise sustainable domestic human resources able to deliver high-quality cancer care

- Human Resource Information Systems may be useful in the development of a platform for healthcare workers and resource distribution. For workforce training, a Global Curriculum in Medical Oncology has been developed by ESMO and the American Society of Clinical Oncology to define the core competencies required for the provision of cancer services.53 Participation in international collaborative networks can augment current workforce capacity through continuous knowledge interchange. Greater evidence is needed to enable adequate numbers of trained health workers to provide high-quality services at the right place and at the right time.

- Encourage international collaborative projects among healthcare professionals to foster excellence

- International collaborative projects can create a scientific network resulting in improved quality of care and knowledge, and foster an exchange of innovative ideas. ESMO is an international society with European roots and a global outreach, and can encourage such collaboration by bringing oncology professionals together, by facilitating educational events, and by engagement with partner societies to augment the quality of cancer services. Strong collaboration is also needed to generate high-quality standards of cancer care, recognising variations that exist between and within countries. High quality must remain a foundational tenet in cancer control—it is more than a policy, it is an oath to our patients and communities.

Conclusion

The 2017 WHO Cancer Resolution is a landmark declaration in cancer prevention and control, building on commitments made by 194 countries to reduce the burden of NCDs and to provide healthcare for all. Governments have been made aware that cancer care is an important health policy issue at the global level. Targets on access to care and mortality reduction have been defined in the 2013–2020 WHO NCD Global Action Plan and the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Action is now needed to realise the goals articulated in these commitments and to implement appropriate policies and programmes for cancer control.

While in some settings significant progress has been made in the management of particular cancer types, the disease has proven to be complex, heterogeneous and therapeutically elusive. The use of modern, effective, yet expensive, anticancer treatments must be juxtaposed against the current gaps in access to high-quality cancer care. Significant disparities in cancer management exist and are arising in many settings globally. A high proportion of populations are not able to access basic health services, significant deficits exist in trained human resources, and there are inadequate funds to finance the provision of basic cancer treatments like antineoplastic compounds, opioids, and radiation therapy.

In light of the magnitude of this challenge, joint efforts from WHO, in collaboration with dedicated cancer organisations like ESMO, are mandatory. The 2016 ESMO Leaders Generation Programme participants heed this call and have made a commitment to action, recognising that as clinicians we have an independent position from other stakeholders, and therefore need to advocate for the best possible outcomes for our patients. As a society, ESMO has committed to global cancer care and has been collaborating with WHO for many years on joint work packages through its ‘official relation status’.54

The history of cancer dates back over four millennia. However, we are at a critical juncture—the pace of change is rapid and promising. But we must remember that our success is framed by the commitments made in the United Nations’ 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, to assure health and well-being for everyone at every stage of life. In this bold United Nations declaration, which will be remembered many years from now, we must see every patient with cancer as our own patient and ensure access and high-quality cancer care for all.

Summary of recommendations

Prioritise efficient use of national resources in a way that assures equity in cancer care that is sustainable, affordable and available to everyone

Adapt the organisation of cancer care and the oncology workforce to promote full population coverage of high-quality comprehensive cancer services, including geographic accessibility

Strengthen regional and subregional partnerships for cancer management, as well as international collaborative projects

Assist health planners by providing tools to help determine the value of cancer care

Provide comprehensive, resource-appropriate and evidence-based cancer service packages that include the cancer regimens of national clinical practice guidelines

Provide for the long-term care needs for all patients with cancer, including vulnerable populations

Assure all patients have enough insurance coverage for adequate cancer care

Develop cancer registries and health information systems that collect standardised data which is comprehensive and accurate so that decision-makers can make informed and evidence-based policy decisions

Acknowledgments

The 2016 ESMO Leaders Generation Programme participants would like to acknowledge the valuable contribution and support to this paper by the WHO staff, the ESMO Leadership, the ESMO Global Policy Committee, the ESMO Public Policy Steering Committee and to Nicola Latino for reviewing the paper. The authors also thank Prof Christoph Zielinski who founded the ESMO Leaders Generation Programme, and Lone Kristoffersen and Katharine Fumasoli for organising the programme.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclaimer: AI is a staff member of WHO. The author alone is responsible for the views expressed in this paper and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy or views of WHO.

Competing interests: AE: Currently conducting research sponsored by AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Celltrion, Novartis, Roche. JT: Advisory Boards for Amgen, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Chugai, Genentech, Lilly, MSD, Merck Serono, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, Symphogen, Taiho, and Takeda. FCi: Advisory Boards: Merck Serono, Amgen, Roche, Bayer, Lilly, Servier. Research funding: Bayer, Roche, Merck Serono. GP: Honorarium for advisory boards or speakers fee: Roche, Celgene, Shire, Merck, Amgen, Lilly, BMS, Servier, Taiho, Halozyme, Sanofi. PC: Honoraria for consultancy/advisory role and/or for lectures from: Bayer, Blueprint Medicines, Deciphera Pharmaceuticals, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Nektar Ther., Novartis, Pfizer, PharmaMar. At his institution, his Unit received funds for research from: AmgenDompé, Arog Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Daiichi Sankyo Pharma, Epizyme Inc., Novartis, PharmaMar. MS: Conducts research sponsored by Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Advisory Boards: BMS, Novartis, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Leo Pharma. Speaker bureau for BMA, Novartis. Travel funding: Novartis, BMS, Astellas, Ipsen. All other authors declare no competing interests related to this paper.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was first published. The author name ’Branoslav Bystricky' has been corrected to ’Branislav Bystricky'. In the Acknowledgements, Lone Kristofferson has been corrected to Lone Kristoffersen.

References

- 1.Global health observatory: the data repository. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017. (accessed 1 Jun 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2013. (accessed 1 Jun 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farmer P, Frenk J, Knaul FM, et al. Expansion of cancer care and control in countries of low and middle income: a call to action. Lancet 2010;376:1186–93. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61152-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Open database: IHME. http://www.healthdata.org/data-visualization/financing-global-health

- 5.Medicines Use and Spending in the U.S.A Review of 2016 and Outlook to 2021. https://www.iqvia.com/institute/reports/medicines-use-and-spending-in-the-us-a-review-of-2016.

- 6.WHA Resolution 70.12. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA70/A70_R12-en.pdf

- 7.United Nations universal declaration of human rights. http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/

- 8.Plummer M, de Martel C, Vignat J, et al. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2012: a synthetic analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4:e609–e616. 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30143-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO. Assessing national capacity for the prevention and control of NCDs. 2016. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/246223/1/9789241565363-eng.pdf?ua=1

- 10.UN SDGs: transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld

- 11.ESMO leaders generation programme. http://www.esmo.org/Career-Development/Leaders-Generation-Programme [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.WHO discussion paper on essential medicines and basic health technologies for noncommunicable diseases: towards a set of actions to improve equitable access in member states. http://www.who.int/nmh/ncd-tools/targets/Final_medicines_and_technologies_02_07_2015.pdf?ua=1

- 13.Varughese J, Richman S. Cancer care inequity for women in resource-poor countries. Rev Obstet Gynecol 2010;3:122–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Exchequer TCot. Budget 2016: documents Bugdet 2016. UK: Exchequer TCot, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Public Financing for Health in Africa: from Abuja to the SDGs. World Health Organization, 2016. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/249527/1/WHO-HIS-HGF-Tech.Report-16.2-eng.pdf?ua=1.

- 16.National Budget 2016 (1395): Budget allocation and citizens participation in Afghanistan. 2016. http://www.budgetmof.gov.af/images/stories/DGB/BPRD/National%20Budget/1395%20Budget/Pre_Budget/MTBF%20-%20Expenditure%20Section.pdf (accessed 23 Nov 2016).

- 17.Open database by World Bank. http://wdi.worldbank.org/table/2.12

- 18.Mayor S. Differences in availability of cancer drugs across Europe. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:1196 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30378-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daniel A, Goldstein A, Tu Y, et al. Global differences in cancer drug prices: a comparative analysis. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(suppl). [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHA Agenda Item A70/27; preparation for the third high-level meeting of the general assembly on the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases, to be held in 2018. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA70/A70_27-en.pdf

- 21.WHO position paper on breast cancer screening.http://www.who.int/cancer/publications/mammography_screening/en

- 22.WHO global health expenditure Atlas, Sept 2014. http://www.who.int/health-accounts/atlas2014.pdf

- 23.Giordano SH et al. Estimating regimen-specific costs of chemotherapy for breast cancer: Observational cohort study. Cancer. 2016 Oct 10. PubMed PMID: 27723214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Dickens C, Joffe M, Jacobson J, et al. Stage at breast cancer diagnosis and distance from diagnostic hospital in a periurban setting: a South African public hospital case series of over 1,000 women. Int J Cancer 2014;135:2173–82. 10.1002/ijc.28861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wallwiener M, Brucker SY, Wallwiener D, et al. Multidisciplinary breast centres in Germany: a review and update of quality assurance through benchmarking and certification. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2012;285:1671 10.1007/s00404-011-2212-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richards MA, Westcombe AM, Love SB, et al. Influence of delay on survival in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review. Lancet 1999;353:1119–26. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02143-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Breast cancer screening: IARC handbook of cancer prevention. Lyon: France: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28.ESMO handbook on cancer in the senior patient.http://oncologypro.esmo.org/Education-Library/Handbooks/Cancer-in-the-Senior-Patient

- 29.Rare cancer europe. http://www.esmo.org/Policy/Rare-Cancers-Europe

- 30.ESMO-SIOPE Adults and Young Adolescents Working Group. http://www.esmo.org/About-Us/Who-We-Are/Educational-Committee/Adolescents-and-Young-Adults-Working-Group

- 31.Mendis S, Davis S, Norrving B. Organizational update: the world health organization global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014; one more landmark step in the combat against stroke and vascular disease. Stroke 2015;46:e121–22. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cancer Control. Knowledge into action: WHO guide for effective programmes: module 1: planning. Geneva: Cancer Control, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013–2020. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. (accessed 1 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gelband H, Sankaranarayanan R, Gauvreau CL, et al. Costs, affordability, and feasibility of an essential package of cancer control interventions in low-income and middle-income countries: key messages from Disease Control Priorities, 3rd edition. Lancet 2016;387:2133–44. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00755-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Atun R, Jaffray DA, Barton MB, et al. Expanding global access to radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:1153–86. 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00222-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011;61:69–90. 10.3322/caac.20107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sullivan R, Alatise OI, Anderson BO, et al. Global cancer surgery: delivering safe, affordable, and timely cancer surgery. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:1193–224. 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00223-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cherny N, Sullivan R, Torode J, et al. ESMO European consortium study on the availability, out-of-pocket costs and accessibility of antineoplastic medicines in Europe. Ann Oncol 2016;27:1423–43. 10.1093/annonc/mdw213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strengthening of palliative care as a component of comprehensive care throughout the life course. WHA resolution 67.19. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA67/A67_R19-en.pdf

- 40.Access to controlled medications programme: developing who clinical guidelines on pain treatment. 2012. http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/quality_safety/ACMP_BrNote_PainGLs_EN_Apr2012.pdf

- 41.ESMO global opioid policy initiative: next steps.http://www.esmo.org/Policy/Global-Opioid-Policy-Initiative/Next-Steps

- 42.Cherny NI, Baselga J, de Conno F, et al. Formulary availability and regulatory barriers to accessibility of opioids for cancer pain in Europe: a report from the ESMO/EAPC Opioid Policy Initiative. Ann Oncol 2010;21:615–26. 10.1093/annonc/mdp581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cherny NI, Cleary J, Scholten W, et al. The Global Opioid Policy Initiative (GOPI) project to evaluate the availability and accessibility of opioids for the management of cancer pain in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, and the Middle East: introduction and methodology. Ann Oncol 2013;24(Suppl 11):xi7–13. 10.1093/annonc/mdt498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cherny NI, Sullivan R, Dafni U, et al. A standardised, generic, validated approach to stratify the magnitude of clinical benefit that can be anticipated from anti-cancer therapies: the European Society for Medical Oncology Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (ESMO-MCBS). Annals of Oncology 2015;26:1547–73. 10.1093/annonc/mdv249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tabernero J, Board EE. Proven efficacy, equitable access, and adjusted pricing of anti-cancer therapies: no ‘sweetheart solution. Annals of Oncology 2015;26:1529–31. 10.1093/annonc/mdv258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.ESMO clinical practice guidelines. http://www.esmo.org/Guidelines

- 47.Eniu A, Torode J, Magrini N, et al. Back to the essence of medical treatment in oncology: the 2015 WHO Model List of Essential Medicines. ESMO Open 2016;1:e000030 10.1136/esmoopen-2015-000030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cherny NI, Sullivan R, Torode J, et al. ESMO International Consortium Study on the availability, out-of-pocket costs and accessibility of antineoplastic medicines in countries outside of Europe. Ann Oncol 2017;28:2633–47. 10.1093/annonc/mdx521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.20th WHO Essential Medicines List (EML) and the 6thWHO Essential Medicines List for Children (EMLc). http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/en

- 50.Economic intelligence unit report supported by ESMO: cancer medicines shortages in Europe: policy recommendations to prevent and manage shortages. http://www.eiu.com/graphics/marketing/pdf/ESMO-Cancer-medicines-shortages.pdf

- 51.WHO. Quality of care: a process for making strategic choices in health systems. http://www.who.int/management/quality/assurance/QualityCare_B.Def.pdf?ua=1

- 52.Guilbert J-J. The World Health report 2006 1 : Working together for health 2. Education for Health: Change in Learning & Practice 2006;19:385–7. 10.1080/13576280600937911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dittrich C, Kosty M, Jezdic S, et al. ESMO / ASCO recommendations for a global curriculum in medical oncology edition 2016. ESMO Open 2016;1:e000097 10.1136/esmoopen-2016-000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ullrich A, Ciardiello F, Bricalli G, et al. ESMO and WHO: 14 years of working in partnership on cancer control. ESMO Open 2016;1:e000012 10.1136/esmoopen-2015-000012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Everybody’s business — strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes. WHO’s framework for action. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 56.WHO. Universal coverage - three dimensions.http://www.who.int/health_financing/strategy/dimensions/en/