Abstract

The objective of this article is to provide a summary of the issues related to occupational safety and health and well-being among workers in the informal economy of Thailand, with a special emphasis on home-based workers. The reviewed literature includes documents and information sources developed by the International Labour Organization, the National Statistical Office of Thailand, peer-reviewed scientific publications, and master’s theses conducted in Thailand. This work is part of a needs and opportunities analysis carried out by the Center for Work, Environment, Nutrition and Development—a partnership between Mahidol University and University of Massachusetts Lowell to identify the gaps in knowledge and research to support government policy development in the area of occupational and environmental health for workers in the informal economy.

Keywords: Thailand, informal economy, informal employment, informal sector, home work, occupational safety and health

Background

The term informal sector was first used in the International Labour Office’s (ILO) 1972 report on Kenya and referred to workers who were not recorded, protected, and regulated by public authorities.1 Three specific attributes stood out: (i) poverty caused by employment that did not enable workers to earn enough to feed their family, gain access to decent health care and education, or acquire safe housing; (ii) survival needs that forced these workers to seek and accept low-productivity income-earning opportunities; and (iii) a globalized division of labor where enterprises introduced more flexible and decentralized production systems to cut costs.1,2 Workers and entrepreneurs have been termed informal because of one chief characteristic: They are not recognized or protected under the legal and regulatory frameworks of national governments.3 When little or no legal or social protection is granted, workers cannot enforce contracts or own property, there is little workplace safety, benefits are lacking, the working time is long, and possibilities for skills development are scarce.3

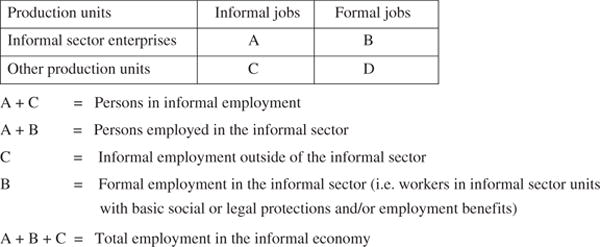

The ILO has developed guidelines for the statistical definition of employment in the informal sector as well as for informal employment,4,5 as they refer to different aspects of informality. Together, these two employment concepts form the informal economy6 (Figure 1). Employment in the informal sector is an enterprise-based concept.6 It consists of private establishments—for example, unregistered or small unincorporated enterprises—which can be characterized by informality (e.g., the legal or registration status, size, bookkeeping practices).6,7 Labor relations in the informal sector are based mostly on casual employment, kinship, or personal relations.7

Figure 1.

The ILO definitions for the informal employment, informal sector employment, and total employment in the informal economy.6

Informal employment is a job-based concept.6 Informal jobs typically lack basic social or legal protections or employment benefits. These can comprise “self-employed workers”—that is, people who run their own informal sector businesses but do not hire employees.8 Informal jobs can also include unpaid workers, in particular family members who contribute to both informal and formal sector businesses. Even though self-employed home-based workers do not hire other employees, they may have unpaid family members working with or contributing to the work being done.9 Some workers can be hired “informally” in formal sector companies. Paid domestic workers employed by households are also considered as typical informal jobs.6,7 Almost everyone employed in the informal sector are in informal employment but not all those in informal employment belong to the informal sector (Figure 1).6

Home-based Workers and Homeworkers

Homeworkers form a significant informal employment workforce. It used to be argued whether a “homeworker” really was a worker or a self-employed, independent entrepreneur who was “home-based.” The ILO’s Home Work Convention, adopted in 1996, provided more clarity to the debate and helped distinguish these two concepts. It defines home work as follows:

The term home work is carried out by a person, to be referred to as a homeworker (i) in his or her home or in other premises of his or her choice, other than the workplace of the employer, (ii) for remuneration; (iii) which results in a product or service as specified by the employer, irrespective of who provides the equipment, materials or other inputs used, unless this person has the degree of autonomy and of economic independence necessary to be considered an independent worker under national laws, regulations, or court decisions.10

The Convention excludes workers who do not have a subordinate relationship with employers and who establish their own direct relationship with the consumer of the end product.10 Dependence on an employer, an absence of control over production methods, and work for wages are differences between homeworkers and the self-employed who use their homes as a workplace. As of April 2015, ten countries have ratified the ILO Home Work Convention (No.177, 1996).11

Prügl and Tinker (1997)12 described four home-based work categories: (i) industrial home work or outwork common in the labor-intensive processes of industries such as footwear, electronics, garment production, and cigarette rolling, (ii) crafts production including basket-weaving, pottery makers, and ornaments makers, (iii) people who make and sell food on the street or in small stores, and (iv) white-collar homeworkers including data-entry clerks, translators, computer programmers, typists, and telemarketers. The organization Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing also includes the personal services category with jobs such as laundry service, beautician, and barber.9 During periods of slow production, homeworkers may work for several employers. Although a lot of necessary mundane work occurs at home, household work and childcare, and “bringing work home from the office” do not constitute home work.13

Objectives of the Study

In this article, we provide a broad overview on issues related to occupational safety and health (OSH) and the well-being among workers in the informal economy of Thailand, with a special emphasis on home-based employment. Previously, we provided a background on selected key international concepts and definitions developed by the ILO. Next, selected findings from national surveys and research studies in Thailand are summarized. Then, we review public policy, training, and research-based interventions to improve home-based workers’ work environment and well-being in the context of Thailand.

Informal Employment and Home-based Work in Thailand

Informal employment has a tremendous significance to the Thai economy. A World Bank study (2010) indicated that the informal economy accounted for about 57 percent of Thailand’s Gross Domestic Product in 2007.14 The National Statistical Office (NSO) of Thailand conducted a survey on the country’s informal labor in 2012. It estimated informal employment at 24.8 million—13.4 million male and 11.4 million female workers—representing about 63 percent of the total Thai labor force in 2012 (39.6 million).15 Among those in informal work, the agriculture sector comprised almost 63 percent, trade and service sector 28 percent, and manufacturing sector 9 percent. The 2012 informal employment survey did not specify what proportion of informal work constituted home-based work.15

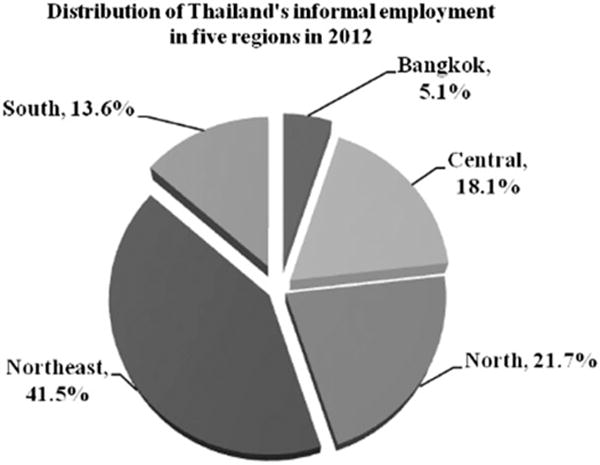

Figure 2 illustrates the total informal employment distribution in five different regions of Thailand. Over 60 percent of the nation’s informal labor is concentrated in northeastern and northern Thailand.15 Thailand’s economic growth has been somewhat weaker in the northeast and north than in other regions. Although the World Bank upgraded Thailand’s status to an upper middle income country in 2011, it was acknowledged that the northeastern and northern regions had not experienced the benefits of economic success in the same way as the rest of the country.16

Figure 2.

Distribution of the total informal employment in Thailand in five regions according to the 2012 NSO survey.15

The Thai NSO conducted the National Home Work Survey in 2007.17 Table 1 describes the total number of households engaging in home work, number of home-based workers (both men and women), and share of female workers reported in different Thai regions. The 2007 survey reports in total over 440,000 homeworkers in over 294,000 households. However, HomeNet Thailand (2009) indicated that due to inconsistent definitions of “home work,” the NSO 2007 estimates were relatively low and that there could be as many as two million home-based workers in the country.18 Table 1 also shows that almost 55 percent of home work households are located either in the north or northeast. The total share of female home-based workers is about 77 percent, in South Thailand as much as 81 percent. The survey identified that most home-based workers were engaged in manufacturing various products such as clothes and other textiles, wooden and paper products, furniture and toys, plastic products or fabricated metals, food products and beverages, and other items.

Table 1.

Number of Households Engaging in Home Work, Total Number of Home-based Workers, Men and Women Workers, and Percentage of Female Home-based Workers in Different Regions of Thailand in 2007.17

| Region of Thailand | Number of households | Total number of home-based workers | Men | Women | Share of home-based women workers (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangkok | 21,618 | 52,118 | 21,079 | 31,039 | 60 |

| Central | 73,819 | 116,583 | 31,792 | 84,791 | 73 |

| North | 79,742 | 102,098 | 18,990 | 83,108 | 81 |

| Northeast | 80,771 | 119,276 | 25,322 | 93,954 | 79 |

| South | 38,340 | 50,176 | 5,542 | 44,634 | 89 |

| Total | 294,290 | 440,251 | 102,725 | 337,526 | 77 |

The OTOP Program of Thailand

The expression “Everyone in Thailand knows what OTOP is”19 describes the popularity of the One Tambon, One Product (OTOP) program. Tambon (or sub-district) is the third government administration level in Thailand (after province and district). The Thai OTOP program follows the model of the One Village, One Product (OVOP) movement of Japan; One Village, One Product was a local government policy that originated in Oita Prefecture by Governor Morihiko Hiramatsu in 1979 and continued until 2003.20 The Governor encouraged residents of the prefecture to select a product or industry distinctive to their village or town and foster it to become nationally and globally marketable.20,21 The movement was founded on three principles emphasizing local ownership values: (i) creation of globally acceptable products/services based on local resources, (ii) self-reliance and creativity, and (iii) human resource development.21

The OTOP program was introduced by the Thai government in 2001 under the Thaksin Shinawatra administration to revitalize the rural economy as part of economic reform as well as to promote quality improvement and marketing of local products and services.21 The Thai government supported the initiative through training, technical assistance, marketing, funding, organizing championships, and developing websites for OTOP groups.21,22 OTOP products include traditional handicrafts, cotton and silk garments, pottery, fashion accessories, household items, food products, and herbs. Many of these products are made in homes; for example, the famous Thai silk is frequently woven by home-based workers. In addition to the village communities, cooperatives and similar associations that often engage home-based labor, OTOP products are also manufactured by small- and medium-sized enterprises in the formal sector.23

One superior product from each Tambon is selected to receive formal branding and rated between one to five stars. A product with five stars is the top grade and considered of exportable quality.22–25 It is important to note that the products made by villages and cooperatives face difficulties compared with ones produced in small- and medium-sized enterprises as they tend to lack production records, standardization, and product quality sufficient to be accepted for export.23 In particular, a major barrier for food products is to obtain a license from the Thai Food and Drug Administration and meet Thai food standards.25 One of the OTOP program goals is to help local producers in expanding their markets so that a larger share of the export economy could be produced in small- and medium-sized enterprises.

OTOP laborers’ working conditions are typically better than those of home-based workers in general—still most home-based work is often conducted without proper recognition from the authorities.26,27 In the next section, we review selected OSH-related research findings among home-based workers conducted in different regions of Thailand.

Home Work OSH Research in Thailand

The Thai NSO Home Work Survey (2007) collected responses on the issues and concerns that home-based workers encounter.17 Unsafe or unhealthy work (reported by almost 25%) emerged as the biggest problem, followed by inadequate compensation (almost 19% of respondents), and instability of work assignments (about 15%). About 32 percent of the respondents did not report any concerns. Table 2 describes unsafe working conditions described by survey respondents from different home work industries. Eyesight loss (55% of respondents) was the most frequently mentioned concern, followed by dust exposure and stresses on the body including musculoskeletal disorders (MSD) (about 15% each). When workers were asked about what assistance they needed, provision of more work orders/assignments emerged the most frequently (32%).

Table 2.

Reported Safety or Health Concerns at Work According to the 2007 National Home Work Survey of Thailand.17

| Safety or health concern at work | Agriculture | Manufacture | Wholesale/retail | Real estate/renting | Other community social service | Others | Total industries (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eyesight loss | 260 | 61,268 | 7,193 | 378 | 106 | 9 | 69,214 (55) |

| Dust exposure | 288 | 17,169 | 1,699 | – | – | 19 | 19,175 (15) |

| Body activity/MSD | 14 | 14,580 | 4,096 | 72 | – | – | 18,762 (15) |

| Hearing loss | 303 | 7,245 | 1,151 | 169 | – | – | 8,868 (7) |

| Unsafe machines | 312 | 6,506 | 409 | – | – | – | 7,227 (6) |

| Hazardous chemicals | – | 1,242 | 916 | – | – | – | 2,158 (2) |

| Total | 1,777 | 108,010 | 15,464 | 619 | 106 | 28 | 125,404 |

Note. MSD = musculoskeletal disorders.

In Thailand, field studies of the work environment among home-based workers have collected data with qualitative interviews, quantitative surveys, walk-through observations, and environmental measurements via direct reading instruments. Pattarapeuksa (2007)28 studied the working conditions and health status of 183 OTOP laborers in the Hatyai district of Songkhla province (in the South) by using an interview survey questionnaire, applying walkthrough checklists for ergonomic and other OSH risk assessment, and conducting environmental measurements for noise, lighting, and temperature. For about 54 percent of the study subjects, OTOP labor was considered their main occupation, and they funded themselves for any needed labor investments, with some support from the Thai Government for materials, information, and marketing. Home-based OTOP workers were involved in the production of food products (e.g., desserts made according to local tradition), accessories (bags), furniture, bird cages, and other. The study rated chemical exposures, workplace hygiene and housekeeping habits, dust exposure, biological hazards, work postures, and machine safety hazards as high risks. Chemical exposures were considered as “high risks” due to lack of information and training on chemical hazards. In particular, few preventive measures for safer chemical use, storage, transportation, and waste management were found. OTOP workers would benefit from a broad range of OSH interventions; however, interventions related to information dissemination and training on chemical safety seem to be particularly important to protect themselves, their family members, and communities from various chemical hazards. Batik production workers were exposed to chemicals from oil color, acrylic paints, ink, and cleaning products. Some dyes and paints contained organic solvents such as toluene and xylene. Bird cage makers were exposed to wood dust that contained chemical residues (e.g., paints and lacquers). Artificial flower makers were exposed to polyester resins that were applied by spraying as well as to adhesive products (i.e., glues) that contained organic solvents such as toluene. Lighting, work hours, heat, and vibration were considered as low to very low risk. One-third of the workers reported underlying diseases, such as hypertension and low-back pain (LBP). Cuts and wounds by sharp objects were the most commonly reported work-related injury (37%). The study’s ergonomic assessment showed workers having MSDs of back, neck, upper and lower extremities.28

Tangkittipaporn and Tangkittipaporn (2006)29 studied 979 home-based handicraft workers in the cities of Chiang Mai and Lumphun in the north. Two-thirds of these workers were women. The participants’ products included food items, herbal/agricultural products, beverages, textiles and clothing, household and decorative items, and silver handicrafts. Approximately 18 percent of participants reported working more than eight hours a day, and almost 71 percent worked seven days a week. The average income was estimated at 4230 baht a month (equivalent to 130 USD). The majority of participants (n = 701 or 72%) reported experiencing at least one physical injury or MSD symptom during the past twelve months including upper extremity MSDs (57%), especially the elbows and shoulders; symptoms of back pain (51%); and lower extremity MSDs (44%), especially the knees and calves.29 These MSD symptoms were attributed to multiple factors, including awkward work postures and static postures (e.g., sitting or standing continuously more than 3–4 hours) due to their work station being located on the ground or on the floor.

Homsombat (2010)30 conducted a cross-sectional study among eighty workers whose main occupations were broom weaving (about 49%) and agricultural work (about 48%) in the Khon Kaen province. About 54 percent of the study subjects were women. The study applied a survey questionnaire, measuring the lighting intensity at workstations, and evaluating physical fitness and ergonomic risks through the Rapid Upper Limb Assessment method. All workers reported repetitive work. The study found high prevalence (84%) of back pain, neck pain, and upper extremity MSDs (neck and LBP were most common). These MSD symptoms were attributed to work stations with poor ergonomic features and psychosocial stress. Slightly over half of the workstations (51%) were below elbow height.30

Manothum et al. (2009)31 studied informal sector workers in four worksites and assessed an OSH management model implementation at each site. Although the study did not investigate home-based workers per se, the study population was involved in production processes typical for home-based workers; therefore, the study findings are applicable here. The four study groups included 22 wood–carvers in the Chiang Mai province, 20 hand-weavers in the Khon Kaen province, 20 artificial flower producers in the Suphanburi province in the Central region, and 23 batik processing workers in the Phuket province in the South. At the beginning of the study, the researchers identified the following OSH concerns: (i) wood dust exposures and noise-induced hearing loss among woodcarvers, (ii) inadequate lighting and MSDs among hand-weavers, (iii) toluene exposure and MSDs among artificial flower producers, and (iv) carbon monoxide and sodium silicate exposures among batik processing workers.31 The study developed an OSH management model which it utilized successfully at each worksite through a participatory approach. The management model at every worksite included the four processes: (i) capacity building through a workshop focusing on participatory learning, (ii) risk analysis by applying an illustrated walk-through checklist, (iii) problem solving based on the ILO Work Improvement in Small Enterprises (WISE) technique, and (iv) monitoring and communication through a follow-up workshop meeting. From the participatory approach, a portable dust collector was designed and built for the wood-carving group, a skylight installed to improve illumination for the hand-weavers, the work area was separated from the chemical storage area for the artificial flower makers, and ventilation was improved for the batik processing workers. As a result, wood dust levels were reduced, lighting was increased, toluene exposures among artificial flower makers were lowered, and measured carbon monoxide levels among batik processers were also decreased.31

In this section, we provided an overview of selected OSH-related research conducted in Thailand. Based on the studies summarized here, home-based workers experience a wide range of occupational hazards and exposures. The next section describes policy, training, and health promotion field study initiatives implemented to protect homeworkers’ safety, health, and well-being.

Legal, Social and Training Frameworks Supporting Home-based Workers

After a long and systematic campaign for homeworkers’ legal and social protection improvements, the efforts by HomeNet Thailand and the Foundation for Labour and Employment Promotion were rewarded.18 In 2010, the Thai Parliament adopted the Homeworkers Protection Act B.E. 2553 which came into effect in May 2011.32 Before discussing the act, it is essential to introduce HomeNet Thailand: A long-term network that has championed homeworkers’ protection.

The aims of HomeNet Thailand are to improve homeworkers’ employment capacities and working conditions by promoting and influencing labor and social protection policies as well as conducting research and disseminating information.33,34 In 1992, it was first established as the Homeworkers Network through an ILO project. Then it operated under the name HomeNet Thailand after the project’s close-down in 1996 and formally registered itself as Foundation for Labour and Employment Promotion in 2003.33 The name HomeNet Thailand is still widely used both nationally and internationally.

Homeworkers Protection Act (2010)

The Homeworkers Protection Act (2010) is a remarkable achievement and could be considered a real step forward toward “formalizing” informal employment. It is expected to impact as many as two million of the nation’s homeworkers.35 The law requires hirers to provide homeworkers with a contract. Furthermore, it mandates industrial establishments who hire homeworkers to pay an equal wage for men and women doing the same job.32 Work safety and health measures have also been taken into account; the law stipulates special protections for pregnant women and anyone under 15 years of age. Chapter 4, Section 21 states that

it is forbidden for anyone to engage home workers to carry out the following works: (1) works involving hazardous materials pursuant to the law governing hazardous materials; (2) works that are to be carried out with the use of tools or machines vibration of which may be hazardous to the persons performing the works; (3) works involving extreme heat or coldness which may be hazardous; (4) other works which may affect health, safety or quality of the environment. The nature or type of works referred to under (2), (3) or (4) shall be those prescribed in the ministerial regulations.32

The law requires the hirers to provide homeworkers with a notice warning of dangerous situations that can arise during their work as well as specifying the necessary safety or protective equipment needed for the work.36

The act is enforced by the Ministry of Labour. This law also established the Home Work Protection Committee, which includes the Undersecretary of State for Labour (as chair); the Director-General of the Department of Labour Protection and Welfare (as secretary); the Director-General of the Department of Employment as well as representatives from the Ministry of Public Health, the Ministry of Industry, the Department of Provincial Administration, and the Department of Local Administration.32 Furthermore, the committee includes three representatives of hirers, three representatives of homeworkers, and up to three qualified experts on home work. The purpose of the committee is to provide policy advice to the Minister of Labour on issues related to protection, promotion, and development of homeworkers, including OSH and skills development. The committee makes recommendations related to regulations and notifications for the implementation of the act, determines homeworkers’ remuneration, and encourages hirers and homeworkers to develop guidelines for good work practices. It also monitors the operations of all stakeholders related to homework and presents a report of the results to the cabinet of ministers at least once a year.32

HomeNet Thailand has been collecting evidence on the impact of the act on homeworkers. In their 2013 report, the network pinpointed several limitations of the act of which three particular ones are important to note here.36 First, the Section 3 defines home work as “work assigned by a hirer in an industrial enterprise to a home worker to be produced or assembled outside of the work place of the hirer or other works specified by the ministerial regulations.” This provision limits the act to homeworkers hired by an industrial enterprise, whereas homeworkers engaged in service work are not covered. Second, based on the findings of ten HomeNet case studies conducted after the act was in effect, many hirers have not complied with the requirement to sign employment contracts with the homeworker. These hirers had also not provided warning notices on hazardous work or what protective equipment or practices were needed for the work. Third, Section 3 of the act defines a homeworker as “a person or group of persons” but not a legal entity such as an organization. If homeworkers form a cooperative or other legal entity, they cannot accept the work under that legal entity, rather they must accept the work as a group of persons by listing all names. HomeNet is concerned that this will discourage homeworkers from organizing themselves.36

Social Protection Policies

It must be acknowledged that during the past three decades, Thailand’s accomplishments in improving the availability of health care for all of the country’s residents are remarkable. In 1977, the nation started developing the district-level primary health-care system for the entire country and in 20 years achieved full geographical coverage.37 In 2001, a universal health-care scheme was implemented by the Thai Government, with financing from the government’s tax revenues. Thailand’s Universal Health Coverage is also known as 30-Baht Health Care Scheme, reflecting a patient’s 30 baht (~$1 USD) copayment for an outpatient hospital visit, hospital admission, annual routine physical exam, or for other service.38 Tangcharoensathien et al. (2013)39 argue that the Thai universal coverage system has improved health financing equity and provided financial risk protection to its citizens, especially in the case of a serious illness. However, the authors conclude that in order to continue its success in the future, the system must extend its coverage area to include effective interventions for improved health promotion to combat noncommunicable diseases (e.g., tobacco and alcohol control, obesity prevention, and support of physical activities).

The Article 40 of the Social Security Act promulgates two insurance schemes.38,40 The first one is the 100-baht monthly payment scheme which is supplemented by a 30-baht government subsidy. The insured receives benefits for injuries, sickness, disability, and death. Another scheme is the 150-baht monthly payment scheme supplemented by a 50-baht government subsidy; the insured receives the same benefits as beneficiaries in the first scheme plus an old-age pension, which becomes accessible at the age of 60. This Universal Pension Scheme provides elderly Thai persons (i.e., 60 years of age or older) 500 baht a month in cash; however, it does not apply to elderly in public facilities and to those who receive other government income support (e.g., pension schemes from government employment).41

ILO Training Approaches to Improve Working Conditions

Since 1980s, the ILO has been developing training programs and materials for small enterprises, informal sector operators, and even home-based workers. Perhaps, the most well-known is the participatory Work Improvements in Small Enterprises (WISE) approach—first published in 1988—and also known as Higher Productivity and a Better Place to Work.42 Its methodology relies on and emphasizes local initiatives of both workers and entrepreneurs by guiding with good local examples. WISE promotes simple, effective, and affordable work environment techniques for small- and medium-sized enterprises to improve both working conditions and productivity. The training method focuses on several physical work environment areas: materials storage and handling, workstation design, machine safety, control of hazardous chemicals, lighting, work-related welfare facilities, work premises, and surrounding environment.43 Several worksite studies have applied and evaluated the WISE- or WISE-originated methodologies both in Thailand31,44,45 and elsewhere.46–48 Earlier in this article, we reviewed the achievements of the Manothum et al. (2009)31 study that employed this methodology in four different worksites in northern and northeastern Thailand. In addition to the current focus areas of WISE, the ILO has been expanding the methodology to include more psychosocial work environment aspects (e.g., working time, positive workplace climate, maternity protection, wages and benefits, and work–family aspects).43

Based on WISE, the ILO developed the Participatory Action Training for Informal Sector Operators approach in the 1990s.49 A decade later, the WISE model was used as the basis for two new methodologies: the Work Improvement in Neighbourhood Development program for agricultural workers and the Work Improvements for Safe Home program targeted to support home-based workers.50,51 The Work Improvements for Safe Home tools were developed in collaboration with Mahidol University and HomeNet Thailand. Its action manual aims to address the immediate needs of home-based workers by: (i) promoting practical, easy-to-implement solutions to improve their work environment and how these solutions can also enable higher work productivity and (ii) encouraging active participation and cooperation of home-based workers at the worksite level and at the community level. Home-based workers who have participated in the Work Improvements for Safe Home program have successfully implemented many low-cost work environment improvements, especially related to ergonomics (e.g., mechanizing manual handling tasks and ergonomically friendlier workstations) and work organization (e.g., separating work areas from living quarters).51

Health Promotion Intervention Studies

Health education and promotion field studies have been conducted among home-based workers. Areeruke (2009)52 conducted a behavioral modification study to address work-related health issues among garment home-based workers in the Sakon Nakhon province in the northeast.52 The study subjects were divided into two groups (experimental and control) of thirty-six garment workers in each. The experimental group received both a general health education program and an occupational health education program. These programs included lectures, group discussion and experience sharing, social support, demonstration and practice, and provision of information and protective equipment. The control group did not receive any education programs. The postintervention questionnaire findings showed that the experimental group had statistically significantly higher mean scores for health risk knowledge, OSH risk identification, and risk prevention compared with the comparison group.52

Kongtiam and Duangsong (2010)53 studied the effectiveness of a health education intervention for reducing LBP among sixty-four home-based fishnet makers grouped into thirty-two workers in an experimental group and thirty-two workers in a control group. The twelve-week intervention phase for the experimental group comprised various activities such as teaching, group discussion, exercise demonstrations (yoga, traditional Thai massage), informational materials (e.g., handbooks), herbal therapy, and training on good ergonomic practices. The results of the postintervention questionnaire showed that the experimental group had statistically significantly higher mean scores for LBP knowledge and decreased LBP levels compared with the control group.53

Conclusions and Recommendations

This article has provided a broad overview on OSH and well-being among workers in the informal economy of Thailand, with a special emphasis on home-based workers. Several important steps have been taken in the strategic areas of OSH policy, research, training, information provision, and education to protect home-based workers. The Thai NSO surveys in 2007 and 2012 on home work and informal economy have provided valuable information to government policy makers. Research studies have evaluated OSH exposures and hazards in a limited number of the many informal sector workplaces. Health promotion studies and training programs based on ILO methodologies have shown that participatory approaches are well suited and successful with the Thai informal workforce. The Homeworkers Protection Act (2010), Universal Health Coverage, and access to social security are all important steps in improving the well-being of workers in the informal economy.

Nevertheless, a more comprehensive OSH picture among workers in the informal economy would be beneficial to understand the magnitude of work-related injuries, illnesses, hazards, and promising practices to prevent them. This could be achieved by adding more OSH-related questionnaire items to Thai NSO’s surveys, or perhaps developing a new NSO survey as a collaborative effort. It is important to conduct comprehensive scientific field studies focusing on evaluating hazardous occupational exposures and the effectiveness of interventions for specific home-based work activities covering the wide range of work represented by the informal economy. More evaluations to understand how the Homeworkers Protection Act (2010) has impacted home-based employment to identify the remaining gaps in regulatory coverage are needed.

The future holds challenges for Thailand, as there are at least two factors that suggest that the country’s informal employment, including home-based work, will increase in the future. First, Thailand recently increased the minimum wage to 300 baht per day (~$9 a day), and this measure is expected to attract more migrant workers into the country.54 Second, in 2015, Thailand is joining the Association of Southeast Asian Nations Economic Community. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations Economic Community agreement will allow free transboundary movement of skilled workers within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations Economic Community countries.55 The Association of Southeast Asian Nations Economic Community agreement is also expected to extend the free movement for all workers in the future.56 Although forthcoming regional challenges may not be small ones, they can create new opportunities for Thai OSH stakeholders to address the areas of public policy, workplace practice, education, and research to protect all workers in any informal employment.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: this work was supported by the Fogarty International Center and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, under the Global Environmental and Occupational Health program awards (1R24TW009560 and 4R24TW009558).

Biographies

Noppanun Nankongnab is a lecturer in the Department of Occupational Health and Safety, Faculty of Public Health, Mahidol University. He earned his PhD in energy technology in 2005 from King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi, Thailand. His research interests are environmental monitoring of chemical pollutants in the working environment, chemical hazards, and ergonomics.

Pimpan Silpasuwan is a professor in the Department of Public Health Nursing, Faculty of Public Health, Mahidol University. Silpasuwan’s research areas include health and safety program development, implementation and evaluation for home-based workers, international migrant workers with a focus on women. Silpasuwan is part of the NIH-funded Mahidol—UMASS Lowell Center for Work Environment, Nutrition and Development (CWEND) Project.

Pia Markkanen is a research professor in the Department of Work Environment, College of Health Sciences, UMASS Lowell. She has been a coinvestigator on the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH)-funded Safe Home Care Project as well as on the NIH-funded Mahidol—UMASS Lowell CWEND Project. Before moving to the United States in 2000, she worked as an OSH Expert at the ILO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific, Bangkok.

Pornpimol Kongtip is an associate professor in the Department of Occupational Health and Safety, Faculty of Public Health, Mahidol University. Her research interests are exposure and health risk assessments and biological monitoring. She coleads a project on occupational research, policy, and capacity building in Thailand funded by the National Institute of Health, USA.

Susan Woskie is a professor in the Department of Work Environment, College of Health Sciences, UMASS Lowell. Her research has focused on exposure assessment for epidemiologic studies and exposure control interventions in a variety of industries and environments. Susan Woskie and Pornpimol Kongtip received a planning grant from NIH to develop a GeoHealth Hub for Occupational and Environmental Health in the ASEAN community. In 2011, they launched the Center for Work Environment Nutrition and Development (CWEND) at Mahidol Faculty of Public Health. She serves on the editorial board of the American Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.International Labour Office. Employment, incomes and equality: a strategy for increasing productive employment in Kenya. Geneva: ILO; www.ilo.org/public/libdoc/ilo/1972/72B09_608_engl.pdf (1972, accessed 21 April 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tokman V. Integrating the informal sector into the modernization process. SAIS Rev Int Aff. 2001;21:45–60. doi: 10.1353/sais.2001.0027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Labour Office. International Labour Conference, 90th Session, 2002, Report VI. Geneva: ILO; Decent work and the informal economy. www.ilo.org/public/english/standards/relm/ilc/ilc90/pdf/rep-vi.pdf (2002, accessed 21 April 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Labour Office. 15th International Conference of Labour Statisticians. Geneva: ILO; Resolution concerning statistics of employment in the informal sector. www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—stat/documents/normativeinstrument/wcms_087484.pdf (1993, accessed 21 April 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Labour Office. The 17th International Conference of Labour Statisticians. Geneva: ILO; Guidelines concerning a statistical definition of informal employment. www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—stat/documents/normativeinstrument/wcms_087622.pdf (2003, accessed 21 April 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 6.International Labour Office. Statistical update on employment in the informal economy. Geneva: ILO Department of Statistics; http://laborsta.ilo.org/applv8/data/INFORMAL_ECONOMY/2012-06-Statistical%20update%20-%20v2.pdf (2012, accessed 21 April 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 7.International Labour Office. Statistical update on employment in the informal economy. Geneva: ILO Department of Statistics; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Labour Office. International classification by status in employment. LABORSTA internet; http://laborsta.ilo.org/applv8/data/icsee.html (2015, accessed 21 April 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) Home-Based workers. http://wiego.org/informal-economy/occupational-groups/home-based-workers (2015, accessed 21 April 2015).

- 10.International Labour Office. The 83rd International Labour Conference session. Geneva: Jun 20, 1996. Home work convention, 1996 (No. 177) www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C177 (1996, accessed 21 April 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 11.International Labour Office. Ratifications of C177 – Home work convention. 177. Geneva: ILO; 1996. www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:11300:0::NO:11300:P11300_INSTRUMENT_ID:312322 (2015, accessed 21 April 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prügl E, Tinker I. Microentrepreneurs and homeworkers: convergent categories. World Dev. 1997;25:1471–1482. DOI: S0305-750X(97)00043-0. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hennon CB, Locker S, Walker R. Gender and home-based employment. London: Auburn House; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider F, Buehn A, Montenegro CE. Shadow economies all over the world: new estimates for 162 countries from 1999 to 2007 Policy Research Working Paper 5356. The World Bank. www.ilo.org/public/libdoc//igo/2010/458650.pdf (2010, accessed 21 April 2015).

- 15.National Statistical Office of Thailand. The informal employment survey. 2012 http://web.nso.go.th/en/survey/data_survey/550712_informal%20labor%202012.pdf (2012, accessed 21 April 2015).

- 16.The World Bank. Thailand Overview. http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/thailand/overview (2015, accessed 27 May 2015).

- 17.National Statistical Office of Thailand. Home work survey. http://web.nso.go.th/en/survey/homework/hwork07.htm (2007, accessed 21 April 2015).

- 18.Homenet Thailand. Policy brief on legal protection. The advocacy for homeworker protection act in Thailand. http://homenetthailand.org/index.php?option=com_phocadownload&view=category&download=10%3Asocial-protection-eng&id=2%3Apolicy&Itemid=10&lang=en (2009, accessed 21 April 2015).

- 19.Boonkam S. One tambon, One product: a marketing campaign for local Thai goods. Presidio Marketing. 2011 Oct 17; www.triplepundit.com/ (2011, accessed 21 April 2015).

- 20.Murayama H, Son K. Understanding the OVOP Movement in Japan: an evaluation of regional one-product activities for future world expansion of the OVOP/OTOP Policy. In: Murayama H, editor. Significance of the regional one-product policy: how to use the OVOP/OTOP movements. Thailand: Thammasat University Printing House; 2012. pp. 191–208. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurokawa K, Tembo F, te Velde DW. Challenges for the OVOP movement in Sub-Saharan Africa – insights from Malawi. Japan and Thailand. Japan: Japan International Cooperation Agency and UK Overseas Development Institute; http://repository.ri.jica.go.jp/dspace/bitstream/10685/38/1/JICA-RI_WP_No.18_2010.pdf (2010, accessed 21 April 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Community Development Department. Manual of one Tambon one product operation: fundamental knowledge about the OTOP program (in Thai) Thailand: Community Development Department, Ministry of Interior; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otakanon B. How to make a successful OTOP product (in Thai, pocket book) www.scribd.com/doc/230380150/568-OTOP-PocketBook (2012, accessed 21 April 2015)

- 24.Community Development Department. Guideline for selection of the top provincial star OTOP (PSO) in 2013 (in Thai) Thailand: Community Development Department, Ministry of Interior; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bussaba N. Master’s Thesis. Mahidol University; Bangkok, Thailand: 2006. Success of food entrepreneurs in OTOP project in Nakhom Phatom province. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coyle S, Kwong J. Women’s work and social reproduction in Thailand. J Contemp Asia. 2000;30:492–506. doi: 10.1080/00472330080000471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chavalitnitikul C. Home work in Thailand. Asian-Pac Newlett Occup Health Saf. 2003;10:12–13. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pattarapeuksa S. Master’s Thesis. Prince of Songkhla University; Songkhla, Thailand: 2006. Working condition, workplace environment and health status of informal labor: a case study of OTOP labor in Hatyai district, Songkhla province. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tangkittipaporn J, Tangkittipaporn N. Evidence-based investigation of safety management competency, occupational risks and physical injuries in the Thai informal sector. Int Cong Ser. 2006;1294:39–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ics.2006.03.074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Homsombat T. Master’s Thesis. Khon Kaen University; Khon Kaen, Thailand: 2010. Back and upper limb pain among informal sector workers of Rom Suk Broom Weaving, Pungtui Sub-district, Nampong district, KhonKaen Province. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manothum A, Rukijkanpanich J, Thawesaengskulthai D, et al. A participatory model for improving occupational health and safety: improving informal sector working conditions in Thailand. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2009;15:305–314. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2009.15.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Home Workers’ Protection Act, B.E 2553. Thailand: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foundation for Labour and Employment Promotion. About us: Foundation for Labour and Employment Promotion. www.homenetthailand.org/index.php/en/abou-tus-en-gb-2 (2015, accessed 21 April 2015).

- 34.Women in Informal Employment Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) HomeNet Thailand. http://wiego.org/wiego/homenet-thailand (2015, accessed 21 April 2015).

- 35.WIEGO. Protection for homeworkers in Thailand. http://wiego.org/informal-economy/protection-homeworkers-thailand (2015, accessed 22 January 2015).

- 36.Homenet Thailand. Homeworkers in Thailand and their legal rights protection. http://wiego.org/sites/wiego.org/files/publications/files/T05.pdf (2013, accessed 21 April 2015).

- 37.Tangcharoensathien V, Limwattananon S, Suphanchaimat R, et al. Health workforce contributions to health system development: a platform for universal health coverage. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:874–880. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.120774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chalamwong Y, Meepien J. Social protection in Thailand’s informal sector. TDRI Q Rev. 2013;28:7–16. doi: 10.1355/ae29-3e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tangcharoensathien V, Pitayarangsarit S, Patcharanarumol W, et al. Promoting universal financial protection: how the Thai universal coverage scheme was designed to ensure equity. Health Res Policy Syst. 2013;11:25. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-11-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.WIEGO. Impact: winning legal rights for Thailand’s’ homeworkers. http://wiego.org/sites/wiego.org/files/resources/files/WIEGO-Winning-legal-rights-Thailands-homeworkers.pdf (2013, accessed 21 April 2015).

- 41.Sakunphanit T, Suwanrada W. Volume 18: successful social protection floor experiences. Global south-south development academy; Chapter 18: 500 Baht Universal pension scheme – Thailand. http://academy.ssc.undp.org/GSSDAcademy/SIE/SIEV1CH18/SIEV1CH18P1.aspx (2011, accessed 21 April 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thurman JE, Kogi K, Louzine AE. Higher productivity and a better place to work: action manual. Geneva: ILO; www.ilo.org/dyn/infoecon/iebrowse.page?p_lang=en&p_ieresource_id=384 (1988, accessed 21 April 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 43.International Labour Office. Work improvements in small enterprises. An introduction to the WISE programme. www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_protect/—protrav/—travail/documents/instructionalmaterial/wcms_152469.pdf (2015, accessed 21 April 2015).

- 44.Krungkraiwong S, Itani T, Amornratanapaichit R. Promotion of a healthy work life at small enterprises in Thailand by participatory methods. Ind Health. 2006;44:108–111. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.44.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manothum A, Rukijkanpanich J. A participatory approach to health promotion for informal sector workers in Thailand. J Injury Violence Res. 2010;2:111–120. doi: 10.5249/jivr.v2i2.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ito A, Sakai K, Kogi K. Development of interactive workplace improvement programs in collaboration with trade associations of small-scale industries. Ind Health. 2006;44:83–86. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.44.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kawakami T, Kogi K. Action-oriented support for occupational safety and health programs in some developing countries in Asia. Int J Occup Saf Ergonom. 2001;7:421–434. doi: 10.1080/10803548.2001.11076499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kawakami T, Kogi K, Toyama N, et al. Participatory approaches to improving safety and health under trade union initiative—experiences of POSITIVE training program in Asia. Ind Health. 2004;42:196–206. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.42.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.International Labour Office. Participatory Action Training for Informal Sector (PATRIS): operator’s manual. www.ilo.org/safework/info/instr/WCMS_112983/lang–en/index.htm (1999, accessed 21 April 2015).

- 50.Kawakami T, Khai TT, Kogi K. Work Improvement in Neighbourhood Development programme (WIND): training programme on safety, health and working conditions in agriculture. Geneva: International Labour Office; www.ilo.org/asia/whatwedo/publications/WCMS_099075/lang–en/index.htm (2005, accessed 21 April 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kawakami T, Arphorn S, Ujita Y. Work improvement for safe home: action manual for improving safety, health and working conditions of homeworkers. Bangkok: International Labour Office; www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—asia/—ro-bangkok/documents/publication/wcms_099070.pdf (2006, accessed 21 April 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Areeruke K. Master’s Thesis. Khon Kaen University; Khon Kaen, Thailand: 2009. Behavioral modification for preventing occupational health problems of informal sector garment workers in bawa sub-district Akatamnuay district. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kongtiam W, Duangsong R. The effectiveness of health education program by an application of self-efficacy theory and social support on behavioral modification for low back pain reducing among informal sector workers (fishing net workers) in Baan Thum sub-district, Muang District, Khon Kaen province. KKU Res J. 2010;10:77–86. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huyen Nguyen N, Walsh J. Vietnamese migrant workers in Thailand – implications for leveraging migration for development. J Iden Migrat Stud. 2014;8:68–94. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Association of Southeast Asian Nations. ASEAN Economic Community. www.asean.org/communities/asean-economic-community (accessed 21 April 2015)

- 56.Orbeta AC. Enhancing labor mobility in ASEAN: focus on lower-skilled workers. Philippine Institute for Development Studies; (Discussion paper series No. 2013-17). http://dirp3.pids.gov.ph/ris/dps/pidsdps1317.pdf (2013, accessed 21 April 2015). [Google Scholar]