Abstract

Informal workers in Thailand lack employee status as defined under the Labor Protection Act (LPA). Typically, they do not work at an employer’s premise; they work at home and may be self-employed or temporary workers. They account for 62.6 percent of the Thai workforce and have a workplace accident rate ten times higher than formal workers. Most Thai Labor laws apply only to formal workers, but some protect informal workers in the domestic, home work, and agricultural sectors. Laws that protect informal workers lack practical enforcement mechanisms and are generally ineffective because informal workers lack employment contracts and awareness of their legal rights. Thai social security laws fail to provide informal workers with treatment of work-related accidents, diseases, and injuries; unemployment and retirement insurance; and workers’ compensation. The article summarizes the differences in protections available for formal and informal sector workers and measures needed to decrease these disparities in coverage.

Keywords: informal workers, formal workers, Occupational Safety and Health, social security, Thailand

Introduction

Thailand has been undergoing a slow process of transition from an agrarian-based economy to one based more on the service and manufacturing/industrial sectors. This change has been driven by Thailand’s efforts to integrate into the global economy and was shaped by global capital movements and national priorities for resource development. In 1960, Thailand was still a rural society with approximately 82 percent of the workforce in agriculture. Twenty years later, slightly more than 70 percent of the workforce was still in agriculture, with approximately 19 percent in the service sector and 11 percent in the relatively new industrial sector.1 By 2012, the total number of employed persons in Thailand was 39.6 million, with agricultural workers comprising only 35 percent of the workforce, while workers in the growing service sector made up the majority of the workforce (41.4 percent), and the manufacturing/industrial sector comprised 23.4 percent of Thai workers.2 Within each of these sectors, the proportion of formal and informal workers varies. The Ministry of Labor defines informal workers as individuals who work in informal economy and do not have employee status under the LPA. Typically, they do not work on the premises of a formal employer; they work without stable wages and are either self-employed or temporary workers. Informal workers do not have legally protected job security, fair wages, or legally mandated occupational safety and health (OSH) programs at work.3 Formal sector workers have an identifiable employer, work at the employer’s premises, and have a variety of legal and social security protections. This paper compares and contrasts these two workforces and the legal protections and safety-net provisions available to each in order to understand the potential policy gaps related to informal sector workers’ OSH in Thailand.

Characteristics of Formal and Informal Workers

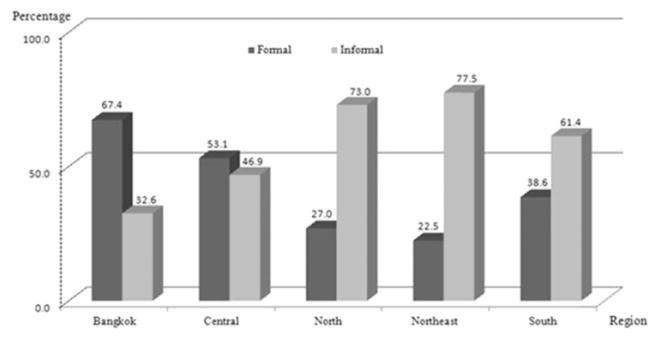

In 2012, formal sector employment in Thailand was approximately 14.8 million (37.4 percent of the workforce). Formal sector employment is regionally concentrated, with 34.5 percent (5.1 million) in the Central region, 20.3 percent (3.0 million) in the Northeast, 17.6 percent (2.6 million) in Bangkok, 14.2 percent (2.1 million) in the South, and 13.5 percent (2.0 million) in the North.2 (Figure 1). Most of those in formal employment (35.2 percent) graduated from secondary school, 32.5 percent completed technical training or have a university degree, and 17.7 percent had only completed elementary education.2 Approximately 9.8 million of the formal workers were registered with the Social Security Office (SSO) in February 2014.4 A 2012 employment survey found that of formal workers, 54.5 percent were in trades and service, 37.6 percent were in manufacturing, and 7.9 percent were in agriculture; while for informal workers, 62.5 percent were in agriculture, 28.3 percent were in trades and service, and 9.2 percent were in manufacturing.2

Figure 1.

Percentage of formal and informal employment by region in 2012.

In 2012, informal sector employment in Thailand was approximately 24.8 million or 62.6 percent of the workforce. The regional concentration of informal employment is greatest in the Northeast with 41.5 percent, followed by the North with 21.7 percent, the Central region with 18.1 percent, the Southern region with 13.6 percent, and Bangkok with 5.1 percent.2 Informal workers are categorized into three subgroups as follows: (1) subcontracted workers and/or home-based workers and self-employed workers engaged in production encouraged through the national One Tambon-One Product (OTOP) program, (2) service workers in restaurants, and as street venders, waste pickers and recyclers, massage workers, public motorcycle rider and cab taxi drivers, and domestic workers, and (3) agricultural workers.3 OTOP is a local entrepreneurship stimulus program designed to encourage village communities to improve their local products’ quality and marketing. One outstanding product from each tambon (township, or preferably, municipal subdistrict) is selected to receive formal branding as its “starred OTOP product”.5

Domestic workers are employed in private homes to clean, cook, launder, and care for children and older people in the family. In the past, young girls were recruited from the rural North and Northeastern regions to come to work as domestic workers in the cities. With the change of social and economic structures and Thailand’s emergence as a newly industrialized country, educational opportunities have expanded, and young Thai girls tend to have sufficient education to be able to obtain nondomestic jobs in shops or factories where they have more freedom.6 Migrant workers from neighboring countries (Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia) are now filling the gap this has left in the labor market for domestic workers. There were 107,777 female workers and 21,490 male workers registered as domestic workers in 2009.6

Informal workers, overall, have less formal education than formal workers. The majority, 15.9 million (64.0 percent), had only a primary education, secondary schooling has been completed by 7.1 million (28.6 percent), and only 1.8 million (7.3 percent) have completed technical training or achieved a university degree.2,3

Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) for Both Sectors

In 1997, the accident rate of formal workers was forty cases per thousand workers. After the first Thai government Master Plan on OSH (2002–2006), the rate of occupational accidents, diseases, and injuries per thousand workers was gradually reduced to 25.6 per thousand workers. However, the cost of workmen’s compensation payments also increased slightly during this time. The occupational disease passive surveillance system was developed for thirty-five diseases in 2003 using a standardized reporting form (called the 506/2). During the second Thai Government OSH Master Plan (2007–2011), the rate of occupational accidents, diseases, and injuries was considerably reduced to 15.8 per thousand workers, but the costs for workmen’s compensation claims continued to increase, fluctuating between 1569.2 and 1734.9 million baht/year (US$533.5–US$589.9 million).3 The majority of these claims were for occupational injuries, with only 3999 occupational disease claims in 2012. The occupational disease cases included 3234 musculoskeletal disorders, 662 skin diseases, sixty lead poisoning cases, twenty-eight hearing loss claims, and five cases of pneumoconiosis. In 2012, the types of accidents and injuries experienced by formal workers were about the same as the previous five years: workers were cut or pierced by objects (23 percent), hit or impacted by objects (16 percent), and had eye injuries (16 percent). These accidents and injuries resulted from incidents involving objects (46 percent), machinery (13 percent), and equipment (12 percent).7

Of 24.8 million informal workers, approximately 4.0 million had injuries or accidents from work in 2012 (161.3 per thousand workers), a rate about ten times higher than that experienced by formal workers. The majority of them had sharp cuts or wounds (68 percent), followed by falls (15 percent), being hit by an object (8 percent), burns (4 percent), vehicle accidents (3 percent), exposure to harmful chemicals (2 percent), and electric shock (1 percent).2 In 2012, the average number of injuries or accidents per day for informal workers was 10,927, which was an increase of 10,003 cases/day from 2011.3

Industrial Development and Neoliberalization in Thailand

In 1960, the population of Thailand was approximately 26 million. In 1957/1958, Field-Marshal Sarit Thanarat’s Revolutionary Council took over the country and established the Import Substitution/Industrialization plan to promote rapid capital development. The Import Substitution/Industrialization aimed to develop domestic technologically based industry and reduce agricultural employment.8 However, by 1980, the general population had almost doubled, and work in the agricultural labor force was still high (70 percent of workforce). Thai rural agricultural productivity is generally low, and the workers generally are poor and have little educational and social support from the government. Growth and industrialization had occurred only in the urban areas, which inevitably led to income inequality between the urban and rural populations.9

The Thai economy suffered severely from the economic crisis of 1997, and as a result, the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and the Asian Development Bank gained influence in Thailand. These organizations emphasized a neoliberal agenda of privatization, deregulation, budget cuts, and austerity measures and a reduced role for the government in the Thai economy. In addition, the International Monetary Fund proposed privatization of state enterprises (especially communications, transport, and energy), reduced restrictions on foreign investment, and increased private sector participation in infrastructure projects.9 This put Thailand in a weak position, and foreign countries exploited the situation by requiring Thailand to sign multiple Free Trade Agreements in order to receive desperately needed foreign investments. These Free Trade Agreements provided tax incentives to encourage investment but did not require corporations to follow international standards of environmental protection and human and labor rights. As a result, the subsequent natural resource extraction (teak logging, mining, fisheries, among others) and the concurrent increase in industrialization led to water shortages that devastated Thai farmers. This resulted in the migration of young people from rural family farms into urban areas to look for work in factories, where labor rights violations were common.10

The use of international funding to finance cheap unregulated manufacturing began to take its toll on traditional local businesses, and they joined the political opposition to privatization and deregulation led by state enterprise employees, members of the parliament, and nongovernmental organizations. The Thai Labor Solidarity Committee was formed in 2001 as a national coalition of thirty-two labor unions, federations, and nongovernmental organizations began a campaign for the promotion and implementation of basic human and labor rights. In 2007, the Thai labor movement called for the rights of freedom of association and collective bargaining without state intervention; equal rights between men and women in all levels of the government. They also called for the ratification of International Labor Organization (ILO) conventions #87—Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention (1948) and #98—Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention (1949) and for changes in the social security system, the minimum wage, and the social welfare system.8 Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra (2001–2006) and the Thai Rak Thai party supported the opposition to the economic changes stemming from neoliberalization, and he proposed a farmer debt moratorium, soft loans for every village, and a thirty-baht universal health-care program.9

Thailand’s National Planning for Labor and Workplace Safety

Thailand’s national planning has established regulations for OSH. These mostly apply to the formal sector. The following section provides an overview of the protections for workers, in the workplace and as part of the social safety net. We explain the context and evolution of informal employment in the economy and the limitations of informal worker protections.

Thailand’s National Economic Development Board issued the First Economic Development Plan in 1961 to serve as a central framework for Thailand’s national development plan; the board’s name was changed in 1972 to the National Economic and Social Development Board, reflecting recognition of social development as an essential part of the national plan. The National Economic and Social Development Board comprised experts in the area of economic and social development. The Board produces a National Economic and Social Development Plan (NESDP) every five years. The NESDP has played an important role in Thailand’s transformation from a poor society to a more affluent newly industrialized country. Over the past three decades, Thailand’s development priorities have mainly focused on economic growth and stability with some attention to poverty alleviation, income inequality, creating a steady energy supply, and addressing environmental degradation.11

The main impetus for policy makers’ concern about workplace health and safety came from a series of industrial accidents in the 1990s. One significant event was the fire at the Kader toy factory on 10 May 1993, which killed 188 workers and injured 469. As a result, the media, nongovernmental organizations, and the public put pressure on policy makers to improve safety standards in Thai factories.1 In August 1997, the Cabinet approved the change date of the annual National Safety week from June 1 to May 10 to commemorate the tragedy.

Since the Thai economy was strong in the early to mid-1990s, the emphasis of the NESDP changed with the eighth plan to include capacity building and the social development of communities, the society, and the nation. The eighth NESDP (1997–2001) also included policy guidelines aimed at reducing occupational injuries and illnesses with a proposal to register informal workers, especially home-based workers, and to increase protections and security for informal workers. The plan included measures to improve the quality of education at all levels by extending basic education from six to nine years in 1999, upgrading the skills and basic knowledge of industrial workers, providing opportunities for underprivileged groups to gain access to basic social services, and a focus on reducing the number of preventable workplace accidents due to the transport of toxic chemicals and fires in high-rise buildings.12 The economic crisis of 1997, however, prohibited the implementation of the eighth plan.

Following the economic crises of 1997–1998, the ninth NESDP (2002–2006) emphasized human development and social protections and incorporated the “Sufficient Economy” philosophy of His Majesty the King. The King’s philosophy urged the country to moderate its development expectations so that individuals and communities could appreciate the resources they have and allow economic development to follow a course of careful risk management.11 The Sufficient Economy philosophy remains a guiding principle for the present and future development of Thailand.13 The ninth plan also included a human and social development fund to promote education, health, skills, and a social welfare system, as well as the development of labor and OSH standards in line with international standards.

Thailand’s main labor law, the LPA of 1998 (reformed in 2004, 2005, and 2008), included coverage for informal economy workers, especially home workers, agricultural workers, women workers, and young workers.14 In addition, the ninth NESDP recommended the Ministry of Labor and SSO to extend social security coverage to informal economy workers.15,16 The OTOP program was promoted during this period to enhance the availability of locally made products in the market. The OTOP program reduced poverty among local people in rural areas all over the country while increasing informal sector employment.17

As a part of the ninth NESDP, the Ministry of Labor’s Department of Labor Protection and Welfare (DLPW) launched its first Master Plan on OSH in 2001, effective for the period 2002–2006.3 The plan’s priorities for improving workplace health and safety included formulating new safety and health regulations and enhancing the training of inspectors to improve their knowledge of labor regulations. In addition, twelve high-hazard industries were targeted for health and safety risk assessments, including the manufacturing of vegetable oil, chemicals and gasses, rubber and plastics, paints, explosives, munitions, and coal and oil refining and products. Other plan components included improving the occupational injury and disease reporting systems, promoting the application of OSH Management Systems based on the ILO guidelines,18 and providing participatory OSH training for small enterprises, home workers, construction workers, and farmers.19 For the targeted industries, the risk assessments were conducted to categorize the risk level for each activity in the workplace. High-risk activities were required to develop plans to reduce the risk. Participatory OSH training was carried out by DLPW, and the cost of the training was covered by the Ministry of Labor.

The plan included a strategy for extending OSH protections to all occupational groups and setting up access to the social security system for those who are self-employed or workers in the informal economy.14 Despite the OSH plan elements, provincial labor protection and welfare offices and the Ministry of Labor’s regional OSH offices in the more industrialized provinces have been unable to adequately address the needs of formal workers in small and medium-sized enterprises. Consequently, protections have not been extended to informal sector workers.

The tenth NESDP (2007–2011) still focused on the Sufficient Economy philosophy of His Majesty the King, as well as social and human development and capacity building.20 The national OSH agenda on “Decent Safety and Health for Workers (2007–2016)” initiated by the Ministry of Labor was approved by the Prime Minister’s Cabinet in December 2007.21 A second OSH Master Plan (2007–2011) proposed five main strategies and thirty-three subprojects with a special emphasis on the enhancement of the skills and performance of OSH personnel in companies and in the DLPW. Additional emphasis was placed on promoting studies to prevent occupational accidents and injuries, the improvement of OSH administration efficiency in the DLPW, and the development of OSH information collection and dissemination systems. The Ministry of Labor developed strategic plans in 2007 and 2011 to address protections for informal workers,22 but neither of these plans was effectively implemented.

The eleventh NESDP was established for the period 2012–2016,23 and the third OSH Master Plan (the National Master Plan on Occupational Safety, Health and Environment—2012–2016) was developed and approved by the government cabinet on 29 November 2011. It is currently in effect.3 It has five strategies to be implemented: promoting labor protection with effective OSH standards, promoting and strengthening the capacity of OSH networks, developing and managing OSH knowledge, developing OSH information system, and developing an effective mechanism for OSH administration. These strategies do not apply to informal sector workers.

Thailand’s Labor Laws and Regulations

Most of Thailand’s labor laws and regulations were promulgated to protect formal workers. The Labor Relations Act (1975) allowed the establishment of worker and employer associations, labor unions, collective bargaining, and dispute settlement.24 Strikes are prohibited in the following industries: postal service, telephone/communication, electrical power distribution, water utilities, medical centers, cooperatives, and rail/land/air/water transport. The act provides the right for Thai employees age twenty or older to form or participate in trade unions. The LPA (1998) regulates labor employment in general, including female labor, child labor, minimum wages, welfare, severance pay, etc.25 The LPA (2008) specifies protections for female employees, employees younger than eighteen years, and pregnant employees when they are employed in hazardous jobs.26

The Thai LPA applies to employees in the private sector but does not apply to all private employees. The law applies neither to public sector employees including employees of state enterprises, employees in public transit organizations, or the Airport Authority of Thailand, nor some private sector workers, such as teachers in private schools. The law does not apply to informal workers, domestic workers, home workers, agricultural workers, seasonal laborers, or employees in nonprofit organizations.14,25

Domestic workers are not eligible for coverage by the Thai social security program, and they have limited coverage under Thai labor laws.6 The LPA 1998 (Amended 2007) requires that domestic workers receive a contract from their employers. These provisions include a requirement that employers inform their domestic employees in advance of contract termination, compensate the employees for their work, and cover the cost of return transportation. Employers of domestic workers are required to pay employee wages at least once a month and annually provide at least six days of paid leave after working for a year.6 The Act, however, does not stipulate working days or hours, overtime pay, or specify a minimum wage for domestic workers.

Domestic employees are protected by law from sexual harassment by their employers (subject to a twenty thousand baht maximum fine [~US$614]). Generally, the law is enforced if an employee reports a violation, but young female domestic workers rarely report sexual harassment for fear of losing their jobs and of possible future consequences related to having filed a complaint. Migrant domestic workers have little access to most of the protections under Thai labor law.6 Between 2002 and 2003, a survey of migrant domestic workers was conducted by the Institute for Population and Social Research at Mahidol University, in collaboration with the Shan Women’s Action Network and the Karen Women’s Organization. Survey results indicated that younger female workers (aged 13–14 years old) have experienced verbal abuse, while those in the 15–17 and 18–24 age groups were more likely to have experienced sexual abuse and unsolicited touching.6 Migrant domestic workers are not protected under OSH regulations.6

The Ministry of Labor is mandated to enforce domestic worker protection laws. In November 2012, Ministerial Regulation No. 14 (2012) entered into force with the main purpose of improving workplace rights for domestic workers in Thailand. It governs employers of domestic workers and provides employees the right to a weekly rest day, traditional public holidays, sick leave, and payment of unused leave days in case of termination, as required under the LPA. Further, it sets a minimum age for employment for domestic workers. Although issues on OSH are not emphasized, several aspects of the regulation align with the ILO Domestic Workers Convention, 2011 (No. 189) and Recommendation (No. 201). The Ministry of Labor, however, lacks sufficient labor inspectors to enforce these labor laws and regulations and to investigate the conditions and complaints of domestic workers. It remains up to individual workers (the victims of employer noncompliance) to make complaints about violations of the laws and regulations in order to gain the attention of the Ministry.

Home-Based Workers

Home-based workers generally are considered informal workers. In 2004, ministerial regulations under the LPA (1998) provided protection to home-based workers.14 Home-based workers who receive wages or home-based contract workers who receive raw materials or production instruments from an employer are covered. Other home-based workers are not covered by the law. The ILO identified a loophole in the laws that omit protections for workers who receive employment from an intermediary employer. This was identified when comparing the scope of regulations for home workers under Thai law and the ILO’s Home Work Convention No. 177. The Thai law did not include intermediary agencies as employers, and therefore the associated regulations were not applied to them.

Under Thai law, the employer of home-based employees must inform the Ministry of Labor of the number of employees, their names, type of work, date of employment, method of payment, raw materials, and tools provided and must sign a contract with the employee. The employer is prohibited from giving hazardous work to home-based employees or hiring children younger than fifteen years of age. The regulation prohibits sexual harassment of women or young workers. The employee has the right to make a complaint to Ministry of Labor inspectors regarding wage payment or also can file a complaint in court. The regulation does not address wages, require training, or require contributions to social security or maternity leave for home-based workers.14

These Thai regulations to protect home-based workers have not been successful in part because they are difficult to enforce and employers and employees misunderstand the requirements. The ILO studied the challenges associated with compliance and enforcement of the law. Employers may not cooperate with the reporting requirement so that the government often remains unaware that employees have been hired. Employees may forego a contract in order to avoid paying taxes and making social security contributions. Labor inspector authority is not clear due to geographic jurisdictional limitations. The inspectors lack understanding of home-based work and how to enforce protections and often have difficulty accessing the home-based workplaces. Also, if the employer does not provide a written contract, the home-based worker may not report them for fear that the employer will cancel their work order.14

Due to these problems, HomeNet Thailand and other informal sector networks put pressure on the government to promulgate the Home Workers Protection Act of 2010.27 This law provides for protection of wages including equal pay for men and women doing the same job. The law has provisions for OSH employers’ responsibilities toward home-based workers, the prohibition of assigning hazardous tasks to pregnant women and children younger than fifteen years old. Employers must provide raw materials, personal protective equipment and take care of home workers in case of work-related injury, accident, or death, including provision of rehabilitation or funeral expenses.27 At the time of this writing, insufficient data exist to be able to report on compliance with the law’s components.

Agricultural Workers

If an agricultural worker has employee status, as defined by the LPA, they are covered under regulations pursuant to the Act. In addition, a 2004 Ministry of Labor regulation, “Labor Protection in the Agricultural Sector,” covers agricultural workers employed all year round in cultivation, husbandry, forestry, salt farming, and fishing. The regulation requires employers to give three holidays for every 180 days of continuous work, and if employees work on an official holiday, they are entitled to double wages. Employees have the right to sick leave with payment for fifteen days, maternity leave without payment and a safe place to live, if they stay with an employer.14 However, Thai farm owners generally do not hire workers for 180 continuous days, making many of these provisions inapplicable.

Self-employed agricultural workers and those who work in the informal agricultural sector are covered by the Notification of the DLPW entitled Guidance on Occupational Safety, Health and Environment for Informal Workers, 2013 (described later).

Protections for Migrant Workers

The LPA (1998) and the amendment in 2007 states that migrant workers must receive the same protections and fair labor practices as Thai employees. Migrant workers who are registered to work in Thailand have to pay a health insurance fee of 1300 baht per year (~US$40) to receive basic medical care at a designated public hospital.6

Thailand shares borders with Myanmar in the west, Lao People’s Democratic Republic in the northeast, and Cambodia in the east. Over the last decade, migrant workers, especially from these three countries, have found many opportunities for low-skilled jobs in Thailand. Some proportion of these migrant workers are registered with the Thai government; however, many more continue working for prolonged periods without documentation. In 2007, of 1,800,000 migrant workers, only 26 percent (460,014 migrant workers) were registered.28 Technically, registered migrant workers have the same labor rights and benefits as Thai workers, but unregistered migrant laborers are classified as illegal immigrants and subject to immediate deportation.28 Increased labor migration is expected with the advent of the ASEAN Economic Community in 2015 which permits the free flow of labor between countries. The total number of unemployed workers in Thailand is less than half a million, which is just a fraction of the total number of foreign workers in the country (estimated at more than two million). The bulk of jobs carried out by migrant workers are low-wage and hard-labor jobs that many Thai workers will not do.29 In 2013, the government of Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra increased the minimum wage to three hundred baht/day (~US$9). As a result, it is expected that Thailand will attract more migrant workers. The minimum wage in three of the ASEAN Economic Community countries that border Thailand—Myanmar, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, and Cambodia—is at least three times lower than that of Thailand.30 After human rights protests following its initial crackdown on unregistered immigrants, the current Thai Military government established a one stop service to register Cambodian migrant workers in four provinces at the border between Thailand and Cambodia so that they could work in Thailand.

Health and Disability/Injury Insurance and Occupational Health Services

The Thai Social Security Administration began operating in 1991 after passage of the Social Security Act (SSA) in 1990. Amendments to the Act were made in 1998 and 2011.31 The SSA does not apply to public officials of Central, Provincial, and Local administrations; teachers or headmasters of private schools; students, nurses, physicians who are employees of schools; and employees of universities or hospitals. The 2011 amendments established a voluntary social security system for informal sector workers. The social security system components are described below, noting formal and informal worker coverage differences.

Social Security

Article 33 of the 1990 SSA covers formal private employees and provides them with inpatient health-care insurance benefits in cases of injury or disease, as well as survivor benefits in case of a covered individual’s death (not for work-related circumstances).32 Additional benefits include childbirth and maternity leave, disability, child allowance, old-age pension, and unemployment insurance. This is a tripartite payment scheme that includes government, employers, and employees who pay 5 percent of their paycheck.31 The SSA covers formal employees whose employment has been discontinued or who have become unemployed due to a lay-off, so long as the employer paid social security contributions for at least twelve months. The worker must inform the SSO within six months after termination and pay 432 baht a month (~US$13) to gain all benefits, except unemployment insurance. These voluntarily insured individuals receive benefits at a higher rate compared to those working with employers.14,15,32 However, only 2.8 percent of the workforce (1,082,650) were voluntarily insured members of the social security system in February, 2014.33

The SSA also allows self-employed (informal sector) persons to be voluntarily insured, but they must pay 3360 baht/year (~US$103/year), without any contribution from the government or employer, and they only receive three benefits: disability, death benefits for their spouse and dependent children, and maternity. Early in the program (2004), only seven self-employed individuals took advantage of this insurance option.15 In May 2011, a revised voluntary social security system for self-employed individuals and informal workers was initiated by the SSO.34 Applicants between fifteen and sixty years of age can choose from one of two optional plans. In the first plan, the informal worker pays seventy baht and the government pays thirty baht per month to cover disability benefits (two hundred baht/day [~US$6] for up to twenty days per year if the informal worker suffers from an injury or illness or is hospitalized for at least two days). (Since 2001, medical treatments have been covered by the universal health care system.35) Informal workers who suffer from a more permanent disability receive payments of 500–1000 baht/month (~US$15–US$30) for fifteen years. If the informal worker dies, their dependents will receive funeral expenses of twenty thousand baht (~US$614).

In the second option, the informal worker pays one hundred baht (~US$3), and the government pays fifty baht per month (~US$1.50). The insured person will receive the same benefits as from the first option, but in addition, there are retirement payments that start at the age of 60.34 There were only 1,657,723 voluntarily insured persons (4.3 percent of workforce) using this option in February 2014.36 Thus, despite the new social security regulations, not all informal workers are being covered.14,32

Formal workers in the SSA are also covered by the Workmen’s Compensation Fund Act (1994)37 to compensate employees who experience work-related injuries or diseases, fatalities, or disability. Regulations issued in 2007 specify compensable occupational diseases based on the employees working conditions or other work-related factors, making it easier for workers to claim compensation. In February 2014, 25.3 percent (9,783,559) of the formal private workforce was insured through this system.4 Workers compensation is not available for informal sector workers.

Medical Care

The first medical welfare scheme was established in 1975, providing the indigent free health-care services at government health facilities. This scheme was transformed into the low-income card scheme in 1981 and extended to the elderly, children younger than twelve years old, and underprivileged groups: the disabled, monks, and war veterans.38,39 The second welfare scheme (Civil Servant Medical Benefit Scheme) for government officials was set up in 1980 to provide health-care services to civil servants and public employees, their spouses, parents, and their children under eighteen years of age. State enterprise employees and their dependents are covered under a similar scheme.31

The first efforts to provide health services to informal workers with a community financing scheme occurred in 1983, which was followed by the Voluntary Health Card Scheme in 1991. These plans did not succeed in providing health care for informal workers because there was no system to provide access to health care for those not classified as poor and covered by the welfare system. At that time, approximately 30 percent of the Thai population (eighteen million people), mostly informal sector workers in lower socioeconomic groups, had no health insurance and lacked access to free medical care. Although exemptions from fees were given by hospital staff on a case-by-case basis, it was these eighteen million uninsured individuals who were the driving force behind the development of the Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS).40 The 1997 and 2007 Thai constitutions asserted that every Thai citizen had a right to health care and that it should be free for the poor.

Access to health services for all was a goal of the eighth NSEDP (1997–2001), and in 2001, Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra of the Thai Rak Thai party introduced a new UCS to ensure that all Thai citizens receive health-care services. 31 The “30 Baht Treats All Diseases Project” (copayment of ~US$1) provided access to preventative care and treatment at government clinics and hospitals. Many studies of illness expenditures have confirmed that the UCS system substantially reduced the financial burden of health care among those with low income and the poor. The UCS mechanism focuses on health promotion and disease prevention through community health volunteers and the use of health centers and community hospitals.40 After nine years of implementation, the UCS members’ satisfaction rose from 83 percent in 2003 to 90 percent in 2010.41

The National Statistic survey of informal workers in 2012 reported that when informal workers suffered an injury requiring hospital treatment, 69 percent (two hundred thousand) used the UCS; nineteen thousand (6.7 percent) used private health insurance; six thousand nine hundred (2.4 percent) used the state enterprise insurance available to family members of government officers; 19 percent paid for themselves; 1.1 percent paid with the help of parents, relatives, and/or friends; and 0.8 percent were covered by employers.3 Clearly informal sector workers have gained substantial benefit from the UCS, and a majority have used the available medical services.

OSH Service for Informal Workers

In August 2013, the DLPW issued a notification entitled Guidance on Occupational Safety, Health and Environment for Informal Workers.42 This Guidance intends to protect informal workers against unsafe and nonhygienic working conditions and environment. It encourages all informal workers, including self-employed persons, to take care of their workplaces in order to promote safety and health at work and to meet applicable standards. The Department is still in the process of developing an administrative structure and mechanisms for the effective administration of this notification as well as to provide OSH services or consultation.

The Thai Ministry of Public Health has strengthened its primary care unit (PCU) systems and the ministerial policy to provide OSH services to informal workers. The Ministry has retrained PCU staff at district levels in basic OSH issues, and the trained PCU staffs have started providing practical OSH services. The PCU staff work in communities and are well placed to know local workers’ immediate needs and to provide sustained services to reduce OSH risks and promote occupational morbidity and fatality prevention in local workplaces.43 The establishment of occupational disease clinics and networks in governmental hospitals was established in 2005 by the director of Bureau of Occupational and Environmental Diseases, Ministry of Public Health, funded by Workmen’s Compensation Fund, SSO.44 This has increased the availability of occupational injury and disease treatment and screening services to both formal and informal workers. The PCUs can refer local occupational disease cases to district, and provincial hospitals. The Ministry of Public health, Bureau of Epidemiology, Department of Disease Control, also runs a national disease surveillance scheme in the country. The occupational disease passive surveillance system developed in 2003 covers ten occupational disease groups; lung and respiratory diseases, physical factor diseases (heat, noise, cold), skin diseases, musculoskeletal diseases, zoonosis diseases, plant caused diseases, metal poisoning diseases, solvent poisoning diseases, gas poisoning diseases, pesticide and other chemical poisoning diseases, and other occupational and environmental diseases. The data showed an average of 17,341 occupational disease cases were reported to the system each year between 2003 and 2012.45 The reported cases in this passive surveillance system come from both formal and informal workers via inpatient and outpatient departments. The hospitals filled in the standardized reporting form (called the 506/2) after diagnosis of an occupational disease. However, not all hospitals report into the system. Hospitals that have an occupational disease clinic may have trained occupational physicians to diagnose cases. Hospitals without an occupational disease clinic can refer patients to other hospitals for diagnosis and treatment. The PCU or health promotion hospitals may not refer patients with occupational disease because the public health officers (generally nurse or bachelors-level public health officer) may not have enough capacity to identify occupational diseases or risk factors. In general, the number of occupational diseases reported is very low, and underreporting is widely suspected. Occupational diseases such as asbestosis and mesothelioma have rarely been identified in Thailand despite the importation and widespread use of asbestos in roofing and floor tiles and automobile brake pads. This situation is believed to result from the lack of physicians trained in occupational medicine and because of the rare use of autopsies in Thai medicine.

Nonregulatory Efforts to Improve OSH in the Informal Sector

The Work Improvement in Neighborhood Development (WIND) OSH program for agricultural workers was first established in Cantho province, Vietnam (1996) as a collaboration between the Occupational Health and Environment Office of Cantho Province and the Institute for the Science of Labor in Japan.46,47 Later, the first WIND training in Thailand was carried out in 1998 in Rayong province in Thailand as a collaboration between Thailand’s Mahidol University Faculty of Public Health, the provincial Department of Public Health, the Institute for Science of Labor, Kawasaki, Japan, and the ILO.48 The WIND OSH training program for agricultural workers is composed of six topics: storage and material transfer; work station design and equipment for work; safety of machines; chemical hazard control; social security and OSH regulations; reduction, reuse, and recycling of materials to reduce global warming. Dr. Kazutaka Kogi, working with the ILO, introduced “WISH” (Work Improvement for Safe Home) for home workers. The program for home workers consisted of the same six topics as WIND with a focus on home workers.48 Manothum and Rukijkanpanich49 reported that the participatory approach of Work Improvement in Small Enterprises (WISE) and WIND is an effective tool to use when promoting the health and safety of informal sectors and when encouraging the workers to voluntarily improve the quality of their own lives. The WIND and WISE programs have been used in Thailand to train agricultural workers by the Ministry of Labor, the ILO, and the Occupational Health and Safety Departments of several Thai universities. Manothum et al. evaluated the implementation of a similar occupational health and safety model for informal sectors in Thailand. This model consisted of four processes: capacity building, risk analysis, problem solving, and monitoring and control. The participants included wood carving, hand-weaving, artificial flower making, and batik processing workers. The results showed that after training, the working conditions of home workers had improved to meet Thai labor standards because these home-based workers were able to create the appropriate technologies to solve their OSH problems. This OSH training and management model was described as having the advantage that informal worker groups can identify their own problems and apply their own appropriate technologies local and global wisdom. This model builds stakeholder capacity and self-sufficiency.50

Recommendations

The Thai government should undertake several measures to increase opportunities for informal workers to join the formal workforce. The government could expand public works programs (infrastructure construction, social and health services, and other programs) which would guarantee at least the minimum wages required for formal employment. This would reduce demand on the social safety nets and increase population participation in the formal economy. The government would need to prioritize human resource development and provide or subsidize job training for current informal workers to increase their capacity for formal employment. This could be an exclusively government program or could include public/private partnerships. The emphasis for job creation would need to be on the expansion of labor-intensive formal industry jobs rather than on technology-intensive industries. Other opportunities to bring informal workers into the formal economy should focus on supporting the expansion of small and medium enterprises, as well as introducing more employment options into OTOP.

Revising the Labor Relation Act to allow all Thai workers to form labor unions would help to increase the power of workers to improve working conditions and economic equity. A labor union of informal workers could help negotiate the social welfare, protection, and wages of informal workers. Intermediary employers of informal sector workers must be added to the definition of “employers” under the LPA.

In Thailand, the philosophy of the King’s Sufficiency Economy recommends the middle path for Thai people at all levels (individual, family, community, economic, national) and framing their expectations to self-support and self-reliance. Our recommendations can be regarded as guidelines that will provide sustainable economic growth and adequate social welfare and protection for informal workers in Thailand, as envisioned by the King’s philosophy.44

Conclusion

According to Schneider, Buehn, and Montenegro’s estimates of the global economy between 1999 and 2007, Thailand is ranked seventh among the countries with the highest ratio of national revenue coming from the informal sector (57.2 percent of the gross domestic product).51,52 Thailand has an informal workforce of 24.6 million (62.6 percent), making these workers major contributors in building the nation’s economic capacity. They work in a variety of occupations and have a broad range of working characteristics, status, and occupationally related problems. They are widely distributed in cities, villages, and rural districts throughout the country. Although informal sector workers have some protections through the LPA (Amendment 2007) and the SSA Section 40, only domestic workers, some home-based workers, and agricultural workers are covered. This legal structure fails to extend effective protection to most Thai informal workers, in large part due to employer noncompliance and employees’ lack of awareness of the laws or inability to attain their rights under the laws. Employers do not make written contracts with informal workers, and informal workers often are willing to work without a contract in order to obtain needed employment. Much informal work is home-based, which presents substantial challenges for establishing health and safety measures, especially if protective equipment is needed. Most of Thai labor and OSH legislation and regulations are designed to protect formal workers who work on employers’ premises. Agricultural and home-based work is not covered under OSH laws and regulation, and the number of government safety or labor inspectors is insufficient to investigate home-based working conditions.

Informal workers often work in substandard conditions and are exposed to various hazards in the workplace without appropriate (if any) safety and health training or safety equipment. The Thai government under Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra had set up a five-year action plan (2012–2016) for the promotion, protection, and development of informal workers including extending protections for and the social security system of informal workers and working to expand the capabilities of informal workers for job expansion and sustainability.22 Specific government organizations and nongovernmental organizations were assigned responsibilities and allocated funding to implement the action plan. Political unrest and government changes have led to changed priorities for meeting the needs of the informal worker population. This is unfortunate, and establishment of practical OSH protection measures for informal workers is urgently needed.43

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This investigation was supported by the Fogarty International Center and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the NIH and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health of the CDC under the Global Environmental and Occupational Health program awards (1R24TW009560 and 4R24TW009558).

Biographies

Pornpimol Kongtip is an associate professor in the Department of Occupational Health and Safety, Faculty of Public Health, Mahidol University. Her research interests are exposure and health-risk assessments and biological monitoring. She coleads a project on occupational research, policy, and capacity building in Thailand funded by the National Institute of Health, USA.

Noppanun Nankongnab is a lecturer in the Department of Occupational Health and Safety, Faculty of Public Health, Mahidol University. His research interests are environmental monitoring of chemical pollutants in the working environment, chemical hazards, and ergonomics.

Chalermchai Chaikittiporn is an associate professor in the Department of Occupational Health and Safety, Faculty of Public Health, Mahidol University. His research interests are occupational epidemiology, occupational safety, risk assessment in industry and ergonomics. He is a former Dean of Faculty of Public Health, former Vice President of Mahidol University.

Wisanti Laohaudomchok is a specialist in Occupational Safety and Health – Professional Level. He works at the Bureau of Occupational Safety and Health, Department of Labour Protection and Welfare, Ministry of Labour, Thailand. His research interests are in occupational health, industrial hygiene, exposure assessment, ergonomics and safety in nanotechnology.

Susan Woskie is a professor at the Department ofWork Environment, University of Massachusetts Lowell. Her research has focused on exposure assessment for epidemiologic studies and exposure control interventions in a variety of industries and environments. Dr. Woskie and Dr. Pornpimol Kongtip received a planning grant from NIH to develop a GeoHealth Hub for Occupational and Environmental Health in the ASEAN community. In 2011, they launched the Center for Work, Environment, Nutrition and Human Development (CWEND) at Mahidol Faculty of Public Health. Dr. Woskie serves on the editorial board of the American Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene.

Craig Slatin is a professor in the Department of Community Health and Sustainability, University of Massachusetts Lowell. He is the editor of New Solutions: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy. He is the principal investigator of The New England Consortium, a hazardous waste worker/emergency responder health and safety training network supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences’ Worker Education and Training Program.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Kelly M, Strazdins L, Dellora T, et al. Thailand’s work and health transition. Int Labour Rev. 2010;149:373–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1564-913X.2010.00092.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Statistics Office. [accessed 7 April 2014];The informal employment survey. http://service.nso.go.th/nso/nsopublish/themes/files/workerOutRep55.pdf.

- 3.Occupational Safety and Health Bureau, Department of Labor Protection and Welfare, Ministry of Labor. [accessed 7 April 2014];National profile on occupational safety and health of Thailand. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/-asia/-ro-bangkok/-sro\bangkok/documents/policy/wcms_192111pdf.

- 4.Social Security Office. [accessed 7 April 2014];Number of insured persons (Article 33): 2005–2014. http://www.sso.go.th/sites/default/files/R&D122009/statisticsmid3_en.html.

- 5.One Tambon One Product (OTOP) Project Information. [accessed 7 April 2014];Historical development of OTOP. http://www.thaitambon.com/OTOP/Info/Info1.htm.

- 6.ILO. [accessed 7 April 2014];Domestic workers in Thailand: their situation, challenges and the way forwards. http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs09/wcms_120274.pdf.

- 7.Social Security Office. [accessed 7 April 2014];Social security statistics. http://www.sso.go.th/wpr/uploads/uploadImages/file/stat2555.pdf.

- 8.Yimprasert J. [accessed 7 April 2014];Thai Labor Campaign Annual Review. http://www.academia.edu/6535852/Thai_Labour_Campaign_Annual_Review_2007.

- 9.Siriprachai S. [accessed 26 September 2014];Industrialization and inequality in Thailand. http://econ.tu.ac.th/archan/rangsun/ec%20460/ec%20460%20readings/thai%20economy/Industrialization/Industrialsation%20and%20Inequality%20in%20Thailand.pdf.

- 10.Hewison K. Neo-liberalism and domestic capital: The political outcomes of the economic crisis in Thailand. J Dev Stud. 2005;41:310–330. [Google Scholar]

- 11.United Nations Development Programme. [accessed 19 June 2014];Thailand Human Development Report 2007. http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/Rio20/images/Sufficiency%20Economy%20and%20Human%20Development.pdf.

- 12.Boonchit W, Natenuj S. [accessed 7 April 2014];The Eighth National Economic and Social Development Plan and current economic adjustment and indicators for monitoring and evaluation of the Eighth Plan. http://www.esri.go.jp/en/archive/wor/abstract/wor64-e.html.

- 13.Chan-o-cha P. [accessed 26 September 2014];Mission statement and policies of the Head of the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) http://dopns.mi.th/Mission/NCPO/HNCPO_Mission%20statement_EN.pdf.

- 14.Tajgman D. [accessed 7 April 2014];Extending labor law to all workers: Promoting decent work in the informal economy in Cambodia, Thailand and Mongolia. http://www.oit.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/-asia/-ro-bangkok/documents/publication/wcms_bk_pb_129_enpdf.

- 15.ILO, Ministry of Labor, and Ministry of Information and Communication Technology. [accessed 7 April 2014];Thailand social security priority and needs survey. http://www.ilo.org/secsoc/information-resources/publications-and-tools/WCMS_SECSOC_1551/lang-en/index.htm.

- 16.ILO. [accessed 7 April 2014];Technical note on the extension of social security to the informal economy in Thailand, Sub-regional office for East of Asia, Bangkok, Thailand. http://www.ilo.org/secsoc/information-resources/publications-and-tools/WCMS_SECSOC_1550/lang-en/index.htm.

- 17.Development Department Community. Manual of One Tambon One Product operation: fundamental of knowledge about OTOP program (Thai language) Bangkok: ATN Production Co., Ltd; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.ILO. [accessed 7 April 2014];Guidelines on occupational safety and health management systems. ILO-OSH. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_protect/@protrav/@safework/documents/normativeinstrument/wcms_107727.pdf.

- 19.Chavalitnitikul C. [accessed 7 April 2014];Development of occupational safety and health management system in Thailand. http//www.aposho.org.

- 20.Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board. [accessed 7 April 2014];The 10th National Health Development Plan, (2007–2011) http://eng.nesdb.go.th.

- 21.National Institute for the Improvement of Working Conditions and Environment (NICE), Department of Labor Protection and Welfare, Ministry of Labor. National profile on occupational safety and health of Thailand. Bangkok: ThepPhan Vanish Co. Ltd; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ministry of Labor (in Thai) [accessed 18 August 2014];Action plan for promotion and protection of informal worker in 2012–2016. http://www.mol.go.th/sites/default/files/downloads/other/PlanStrategy_Labor55-59Minister.pdf.

- 23.Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board. [accessed 7 April 2014];The 11th National Health Development Plan, (2012–2016) http://eng.nesdb.go.th.

- 24.Department of Labor Protection and Welfare, Ministry of Labor. [accessed 18 August 2014];Labor Relation Act B.E. 2518. 1975 http://www.mol.go.th/sites/default/files/images/other/laborRelation2518_en.pdf.

- 25.Department of Labor Protection and Welfare, Ministry of Labor. [accessed 18 August 2014];Labor Protection Act B.E.2541. 1998 http://www.labor.go.th/en/attachments/article/18/Labor_Protection_Act_BE1998.pdf.

- 26.Department of Labor Protection and Welfare, Ministry of Labor. [accessed 18 August 2014];Labor Protection Act B.E 2551. 2008 http://www.labor.go.th/en/attachments/article/19/Labor_Protection_Act_BE2008.pdf.

- 27.Department of Labor and Protection Welfare, Ministry of Labor. [accessed 18 August 2014];Home-Based Workers Protection Act, B.E.2553. http://thailaws.com/law/t_laws/tlaw0473.pdf.

- 28.Martin P. [accessed 16 July 2014];The economic contribution of migrant workers to Thailand: towards policy development. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/-asia/-ro-bangkok/documents/publication/wcms_098230pdf.

- 29.Ducanes G. [accessed 7 April 2014];Labor shortages, foreign migrant recruitment and the portability of qualifications in East and South-East Asia. http//apmagnet.ilo.org.

- 30.Runckel CW. [accessed 16 July 2014];Several Southeast Asian countries announced new minimum wage at the beginning of year 2013. http://www.business-inasia.com/asia/minimum_wage/Minimum_wages_in_Asia/minimum_wage_in_asia.html.

- 31.Tangcharoensathien V, Supachutikul A, Lertiendumrong J. The social security scheme in Thailand: what lessons can be drawn? Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:913–923. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00392-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Social Security Office, Ministry of Labor. [accessed 7 April 2014];Social Security Act B.E. 2533. http://www.sso.go.th/sites/default/files/Social%20%20security%20act.pdf.

- 33.Social Security Office. [accessed 7 April 2014];Number of insured persons (Article 39): 2005–2014. http://www.sso.go.th/sites/default/files/R&D122009/statisticsmid39_en.html.

- 34.Social Security Office. [accessed 23 August 2014];Social Security System in Section 40. http://www.sso.go.th/wpr/category.jsp?lang=th&cat=883.

- 35.Pannarunothai S, Patmasiriwat D, Srithamrongsawat S. Universal health coverage in Thailand: ideas for reform and policy struggling. Health Policy. 2004;68:17–30. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8510(03)00024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Social Security Office. [accessed 7 April 2014];Number of insured persons (Article 40): 2004–2013. http://www.sso.go.th/sites/default/files/R&D122009/statisticsmid40_en.html.

- 37.Social Security Office, Ministry of Labor. [accessed 7 April 2014];Workmen’s Compensation Fund Act, B.E. 2537. http://www.sso.go.th/sites/default/files/userfiles/file/workmen_s_compensation_act.pdf.

- 38.Pannarunothai S, Mills A. The poor pay more: health-related inequality in Thailand. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:1781–1790. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00287-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hanvoravongchai P. Health financing reform in Thailand: toward universal coverage under fiscal constraints. Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yiengprugsawan V, Kelly M, Seubsman S-A, et al. The first 10 years of the Universal Coverage Scheme in Thailand: review of its impact on health inequalities and lessons learnt for middle-income countries. Australas Epidemiol. 2010;17:24–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Health Insurance System Research Office. Thailand’s Universal Coverage Scheme: achievements and challenges. An independent assessment of the first 10 years (2001–2010) Nonthaburi, Thailand: Health Insurance System Research Office; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ministry of Labor (in Thai) [accessed 17 July 2014];Notification entitled Guidance on Occupational Safety, Health and Environment for Informal Workers. http://www.shawpat.or.th/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=415%3A-m-ms&catid=57%3A-m-m-s&Itemid=165&lang=th.

- 43.Siriruttanapruk S, Wada K, Kawakami T. Promoting occupational health services for workers in the informal economy through primary care units. Bangkok: ILO; 2009. ILO Asia-Pacific Working Paper Series. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krongkaew M. [accessed 10 June 2014];Economic growth and social welfare: experience of Thailand after 1997 economic crisis. http://www.eclac.cl/brasil/noticias/noticias/4/9794/MedhiKrongkaew.pdf.

- 45.Bureau of Epidemiology, Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health. [accessed 20 June 2014];Report of health surveillance system for occupational and environmental diseases. http://www.boe.moph.go.th/files/report/20110406_26449313.pdf.

- 46.Bureau of Occupational Safety and Health, Department of Labor and Protection Welfare, Ministry of Labor. OSH improvement for informal sector. Bangkok: Thanapress Co Ltd; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kawakami T, Van VN, Theu NV, et al. Participatory support to farmers in improving safety and health at work: building WIND farmer volunteer networks in Viet Nam. Ind Health. 2008;46:455–462. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.46.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.ILO. [accessed 9 June 2014];WIND training programme in Cambodia, Mongolia and Thailand. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@asia/@ro-bangkok/@sro-bangkok/documents/publication/wcms_120494.pdf.

- 49.Manothum A, Rukijkanpanich J. A participatory approach to health promotion for informal sector workers in Thailand. J Inj Violence Res. 2010;2:111–120. doi: 10.5249/jivr.v2i2.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Manothum A, Rukijkanpanich J, Thawesaengskulthai D, et al. A participatory model for improving occupational health and safety: improving informal sector working conditions in Thailand. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2009;15:305–314. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2009.15.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thailand Outlook. [accessed 7 April 2014];Thailand ranked 7th in countries with highest informal sector. http://www.accessmylibrary.com/article-1G1-233486900/thailand-thailand-ranked-7th.html.

- 52.Schneider F, Buehn A, Montenegro CE. [accessed 9 June 2014];Shadow economies all over the World: new estimates for 162 countries from 1999 to 2007. http://www.econ.jku.at/members/Schneider/files/publications/LatestResearch2010/SHADOWECONOMIES_June8_2010_FinalVersion.pdf.