Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a versatile opportunistic pathogen capable of infecting a broad range of hosts, in addition to thriving in a broad range of environmental conditions outside of hosts. With this versatility comes the need to tightly regulate its genome to optimise its gene expression and behaviour to the prevailing conditions. Two-component systems (TCSs) comprising sensor kinases and response regulators play a major role in this regulation. This minireview discusses the growing number of TCSs that have been implicated in the virulence of P. aeruginosa, with a special focus on the emerging theme of multikinase networks, which are networks comprising multiple sensor kinases working together, sensing and integrating multiple signals to decide upon the best response. The networks covered in depth regulate processes such as the switch between acute and chronic virulence (GacS network), the Cup fimbriae (Roc network and Rcs/Pvr network), the aminoarabinose modification of lipopolysaccharide (a network involving the PhoQP and PmrBA TCSs), twitching motility and virulence (a network formed from the Chp chemosensory pathway and the FimS/AlgR TCS), and biofilm formation (Wsp chemosensory pathway). In addition, we highlight the important interfaces between these systems and secondary messenger signals such as cAMP and c-di-GMP.

Keywords: Two-component signalling, multikinase network, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, secondary messengers, virulence

Two-component systems controlling the virulence of the opportunistic pathogen, Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas aeruginosa has a remarkably diverse ability to thrive in many different environments both outside and within a host. To be successful in these diverse situations, P. aeruginosa needs to sense its environment, decide upon an appropriate response and modify its behaviour accordingly to better suit prevailing conditions. Regulatory networks are key to this decision-making process. Pseudomonas aeruginosa has a large genome (6.3 Mb for the reference PAO1 strain), reflecting the diverse range of environments and hosts that it can inhabit, and just under 10% of its genes are dedicated to these regulatory networks (Stover et al.2000). Two-component systems (TCSs) comprising sensor kinases (SKs) and response regulators (RRs) (Stock, Robinson and Goudreau 2000) play a major role in these regulatory networks with P. aeruginosa having 64 SKs, 72 RRs and 3 Hpt proteins (Rodrigue et al.2000; Stover et al.2000).

As an opportunist pathogen, being capable of both acute and chronic infection, P. aeruginosa has a multitude of virulence factors and antibiotic resistance determinants (Driscoll, Brody and Kollef 2007; Gooderham and Hancock 2009; Coggan and Wolfgang 2012). Well over 50% of the TCSs of P. aeruginosa have been linked to virulence, controlling either virulence-related behaviour or contributing towards in vivo fitness and colonisation ability. This number has grown considerably in recent years, primarily due to the successful application of whole-genome-based methodologies for identifying genes involved in virulence, such as Tn-Seq approaches using animal infection models, and the study of pathoadaptive mutations in isolates from cystic fibrosis (CF) patients (Table 1 major).

Table 1.

The TCSs that have been implicated in P. aeruginosa virulence and/or antibiotic resistance.

| Sensor kinase | Response regulator | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAO1 | PA14 | PAO1 | PA14 | Protein product | Signalling molecule | Functional description | Chronic (Potvin et al.2003) | Pathoadaptive (Marvig et al.2013) | Pathoadaptive (Marvig et al.2015) | Fitness Tn-Seq (Skurnik et al.2013) | Acute burn model (Turner et al.2014) | Chronic wound model (Turner et al.2014) | CF sputum Tn-Seq (Turner et al.2015) | References |

| Multikinase networks | ||||||||||||||

| aGacS network controlling the acute/chronic switch | ||||||||||||||

| PA0928 | PA14_52260 | PA2586 | PA14_30650 | GacS-GacA | Solvent extractable extracellular signal | GacA–GacS system. Virulence, quorum-sensing-dependent regulation of exoproducts and virulence factors, biofilm formation, antibiotic resistance, swarming motility, iron metabolism and T3/T6 secretion | Y | Y | Reimmann et al. (1997); Rahme et al. (2000); Parkins, Ceri and Storey (2001); Heeb, Blumer and Haas (2002); Goodman et al. (2004); Soscia et al. (2007); Brencic et al. (2009); Goodman et al. (2009); Frangipani et al. (2014) | |||||

| PA1611 | PA14_43670 | Unknown | PA1611-HptB-HsbR phosphorelay. Acute/chronic infection cycle in conjunction with the GacS network and has been shown to directly interact with RetS | Y | Y | Lin et al. (2006; Hsu et al. (2008); Kong et al. (2013); Bhagirath et al. (2017) | ||||||||

| PA2824 | PA14_27550 | SagS | Unknown | Regulates the motile-sessile switch in biofilm formation. Linked with the GacS and HptB networks and the SK BfiS | Y | Hsu et al. (2008); Petrova and Sauer (2010, 2011) | ||||||||

| PA4197 | PA14_09680 | PA4196 | PA14_09690 | BfiS-BfiR | Unknown | Biofilm formation/maintenance | Y | Y | Y | Petrova and Sauer (2009) | ||||

| PA3345 | PA14_20800 | PA3346 | PA14_20780 | HptB-HsbR | Unknown | HptB-mediated phosphorelay, swarming motility and biofilm formation | Y | Y | Y | Hsu et al. (2008); Bhuwan et al. (2012) | ||||

| PA3974 | LadS | Ca2+ | Regulates virulence, biofilm formation and T3 secretion/cytotoxicity via GacS | Y | Y | Ventre et al. (2006); Chambonnier et al. (2016) | ||||||||

| PA4856 | PA14_64230 | RetS | Kin cell lysate | Regulates virulence, biofilm formation and T3/T6 secretion/cytotoxicity via GacS | Y | Y | Y | Goodman et al. (2004); Laskowski, Osborn and Kazmierczak (2004); Moscoso et al. (2011); LeRoux et al. (2015) | ||||||

| aRoc network controlling the fimbrial cup genes | ||||||||||||||

| PA3044 | PA14_24720 | PA3045 | PA14_24710 | RocS2-RocA2 | Unknown | RocA2–RocS2 system. Regulation of fimbriae adhesins and antibiotic resistance | Y | Y | Y | Kulasekara et al. (2005); Sivaneson et al. (2011) | ||||

| PA3946 | PA14_12820 | PA3947 PA3948 | PA14_12810PA14_12780 | RocS1 (SadS)-RocR (SadR) RocA1 (SadA) | Unknown | RocS1–RocR–RocA1 (SadA–SadR–SadS system). Biofilm maturation, fimbrial genes, T3 secretion and antibiotic resistance. RocA1 contains EAL output domain, RocR is a RocA1 antagonist | Y | Gallagher and Manoil (2001); Kuchma, Connolly and O’Toole (2005); Kulasekara et al. (2005); Sivaneson et al. (2011) | ||||||

| aRcsCB/PvrSR network controlling the cupD fimbrial genes | ||||||||||||||

| PA14_59800 | PA14_59790 | PvrS-PvrR | Unknown | Phenotypic variation, antibiotic resistance, biofilm formation. Controls cupD fimbriae genes | Drenkard and Ausubel (2002); Mikkelsen et al. (2009, 2013) | |||||||||

| PA14_59780 | PA14_59770 | RcsC-RcsB | Unknown | Biofilm formation. Controls cupD fimbriae genes | Mikkelsen et al. (2009, 2013) | |||||||||

| Network controlling ethanol oxidation | ||||||||||||||

| PA1976/PA1979 | PA14_38970 PA14_38910 | PA1978 PA1980 | PA14_38930 PA14_38900 | ErcS'/EraS-ErbR/EraR | Possible cytosolic metabolites | Regulates ethanol oxidation control and it is implicated in biofilm specific antibiotic resistance. PA14_38910 is essential | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Mern et al. (2010); Beaudoin et al. (2012) | ||

| PA1992 | PA14_38740 | ErcS | Possible cytosolic metabolites | Regulates ethanol oxidation control and it is implicated in biofilm specific antibiotic resistance | Y | Mern et al. (2010); Beaudoin et al. (2012) | ||||||||

| PA3604 | PA14_17670 | ErdR | Unknown | Ethanol oxidation control, implicated in biofilm-specific antibiotic resistance | Y | Mern et al. (2010); Beaudoin et al. (2012) | ||||||||

| Network detecting phosphate limitation and tricarboxylic acids | ||||||||||||||

| PA0757 | PA14_54500 | PA0756 | PA14_54510 | TctE-TctD | Tricarboxylic acids | Controls expression of tricarboxylic acid uptake system | Y | Y | Y | Bielecki et al. (2015) | ||||

| PA5361 | PA14_70760 | PA5360 | PA14_70750 | PhoR–PhoB | Inorganic phosphate | Quorum sensing and swarming motility | Y | Y | Blus-Kadosh et al. (2013); Faure et al. (2013); Bielecki et al. (2015) | |||||

| aChp/FimS/AlgR network controlling twitching motility, virulence and biofilm formation | ||||||||||||||

| PA0413 | PA14_05390 | PA0408 PA0409 PA0414 | PA14_05320 PA14_05330PA14_05400 | ChpA/PilG/ PilH/ChpB | Unknown | Chemosensory pili (Pil–Chp) system, twitching motility and cAMP levels. Virulence genes | Y | Y | Darzins and Russell (1997); Whitchurch et al. (2004); Bertrand et al. (2010); Fulcher et al. (2010); Luo et al. (2015); Persat et al. (2015); Inclan et al. (2016); Silversmith et al. (2016) | |||||

| PA5262 | PA14_69480 | PA5261 | PA14_69470 | FimS(AlgZ)-AlgR | Unknown | Virulence, alginate biosynthesis, twitching and swarming motility, biofilm formation, cyanide production, cytotoxicity and type III secretion system gene expression | Y | Y | Y | Intile et al. (2014); Okkotsu, Little and Schurr (2014) | ||||

| aNetwork controlling the aminoarabinose modification of LPS | ||||||||||||||

| PA1179 | PA14_49170 | PA1179 | PA14_49180 | PhoQ–PhoP | Mg2+ | Low Mg2+ signal. Polymyxin, antimicrobial peptide and aminoglycoside resistance. Virulence, swarming motility and biofilm formation | Y | Y | Ernst et al. (1999); Macfarlane et al. (1999); Macfarlane, Kwasnicka and Hancock (2000); Ramsey and Whiteley (2004); McPhee et al. (2006); Jochumsen et al. (2016) | |||||

| PA1798 | PA14_41270 | PA1799 | PA14_41260 | ParS-ParR | Cationic peptides | Multidrug resistance, quorum sensing, phenazine production and swarming | Y | Fernández et al. (2010); Muller, Plésiat and Jeannot (2011); Wang et al. (2013) | ||||||

| PA3078 | PA14_24340 | PA3077 | PA14_24350 | CprS-CprR | Antimicrobial peptides | Triggers LPS modification and adaptive antimicrobial peptide resistance | Y | Fernández et al. (2010) | ||||||

| PA4380 | PA14_56940 | PA4381 | PA14_56950 | ColS-ColR | Zn2+ | Polymyxin resistance, mutants have decreased virulence in a Caenorhabditis elegans model and decreased cell adherence | Y | Y | Y | Garvis et al. (2009); Gutu et al. (2013) | ||||

| PA4777 | PA14_63160 | PA4776 | PA14_63150 | PmrB–PmrA | Mg2+ | Induced by low Mg2+ and cationic antimicrobial peptides. Polymyxin B, colistin and antimicrobial peptide resistance | Y | Y | Y | McPhee, Lewenza and Hancock (2003); Moskowitz, Ernst and Miller (2004); McPhee et al. (2006); Lee and Ko (2014) | ||||

| Other TCSs implicated in virulence | ||||||||||||||

| PA0033 | PA14_00420 | HptC | Unknown | Histidine containing phosphotransfer protein | Y | Y | ||||||||

| PA0034 | PA14_00430 | Unknown | PA0034 is repressed during in vitro growth in CF sputum medium. Located directly upstream of hptC (PA0033) | Y | Y | Palmer et al. (2005) | ||||||||

| PA0173 | PA14_02180 | CheB | Unknown | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||

| PA0178 | PA14_02250 | PA0179 | PA14_02260 | Unknown | Y | Y | ||||||||

| PA0991 | PA14_51480 | HptA | Unknown | Histidine containing phosphotransfer protein | Y | Y | ||||||||

| PA0464 | PA14_06070 | PA0463 | PA14_06060 | CreC–CreB | Penicillin-binding protein 4 | Catabolism. Swarming and swimming motility. Antibiotic resistance, biofilm and global gene regulation | Y | Y | Wagner et al. (2007); Zamorano et al. (2014) | |||||

| PA0600 | PA14_07820 | PA0601 | PA14_07840 | AgtS-AgtR | Peptidoglycan | Involved in sensing peptidoglycan and controlling virulence | Y | Y | Y | Korgaonkar et al. (2013) | ||||

| PA0930 | PA14_52240 | PA0929 | PA14_52250 | PirR–PirS | Unknown | Iron acquisition | Y | Y | Y | Y | Vasil and Ochsner (1999) | |||

| PA1098 | PA14_50200 | PA1099 | PA14_50180 | FleS–FleR | Unknown | Flagellar motility and adhesion to mucin. FleS likely cytoplasmic sensor | Y | Y | Ritchings et al. (1995); Dasgupta et al. (2003) | |||||

| PA1136 | PA14_46980 | PA1135 | PA14_49710 | Unknown | Antibodies against PA1136 found in CF patient sera | Beckmann et al. (2005) | ||||||||

| PA1158 | PA14_49420 | PA1157 | PA14_49440 | Unknown | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||

| PA1243 | PA14_48160 | Unknown | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| PA1336 | PA14_46980 | PA1335 | PA14_46990 | AauS-AauR | Unknown | Y | ||||||||

| PA1396 | PA14_46370 | PA1397 | PA14_46360 | DSF | Interspecies signalling. Responds to diffusible signal factor (DSF) and regulates biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance | Y | Ryan et al. (2008) | |||||||

| PA1438 | PA14_45870 | PA1437 | PA14_45880 | Unknown | Y | |||||||||

| PA1456 | PA14_45620 | CheY | Unknown | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||

| PA1458 | PA14_45590 | PA1459 | PA14_45580 | Unknown | Y | Y | ||||||||

| PA1636 | PA14_43350 | PA1637 | PA14_43340 | KdpD-KdpE | Unknown | Y | Y | |||||||

| PA1785 | PA14_41490 | NasT | Unknown | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||

| PA2137 | PA14_36920 | Unknown | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| PA2177 | PA14_36420 | Unknown | Y | Y | Y | |||||||||

| PA2376 | PA14_33920 | Unknown | Y | Y | Y | |||||||||

| PA2480 | PA14_32570 | PA2479 | PA14_32580 | Unknown | Essential in PA14 | Y | Y | |||||||

| PA2524 | PA14_31950 | PA2523 | PA14_31960 | CzcS–CzcR | Zinc, cadmium or cobalt | Regulates metal resistance and antibiotic resistance and pathogenicity | Y | Hassan et al. (1999); Dieppois et al. (2012) | ||||||

| PA2571 | PA14_30840 | PA2572 | PA14_30830 | Unknown | Affects motility, virulence and antibiotic resistance. Works with PA2573 (an MCP homologue) | Y | McLaughlin et al. (2012) | |||||||

| PA2583 | PA14_30700 | Unknown | Y | |||||||||||

| PA2656 | PA14_29740 | PA2657 | PA14_29730 | BqsS-BqrR/(CarS-CarR) | Extracellular Fe(II) and CaCl2 | Biofilm decay, ferrous iron sensing, antibiotic resistance and cationic stress tolerance. Maintains Ca2+ homeostasis, regulates pyocyanin, swarming and tobramycin sensitivity. PA14_29740 is an essential gene | Y | Y | Y | Y | Dong et al. (2008); Kreamer, Costa and Newman (2015); Guragain et al. (2016) | |||

| PA2687 | PA14_29360 | PA2686 | PfeS–PfeR | Enterobactin | Iron acquisition | Y | Y | Dean, Neshat and Poole (1996) | ||||||

| PA2798 | PA14_27940 | Unknown | Described as essential in PA14 | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||

| PA2810 | PA14_27800 | PA2809 | PA14_27810 | CopS–CopR | Copper | Metal and imipenem resistance | Y | Y | Y | Teitzel et al. (2006); Caille, Rossier and Perron (2007) | ||||

| PA2882 | PA14_26810 | PA2881 | PA14_26830 | Unknown | Y | Y | ||||||||

| PA2899 | PA14_26570 | Unknown | Y | |||||||||||

| PA3191 | PA14_22960 | PA3192 | PA14_22940 | GtrS-GltR | 2-Ketogluconate | Glucose transport and type III secretion cytotoxicity | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Wolfgang et al. (2003); O’Callaghan et al. (2012); Daddaoua et al. (2014) | ||

| PA3206 | PA14_22730 | PA3204 | PA14_22760 | CpxA-CpxR | Unknown | Antibodies against PA3206 found in CF patient sera. Implicated in cell envelope stress response. Activates MexAB-OprM efflux pump expression and enhances antibiotic resistance | Y | Y | Y | Beckmann et al. (2005); Yakhnina, McManus and Bernhardt (2015); Tian et al. (2016) | ||||

| PA3271 | PA14_21700 | Unknown | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| PA3349 | PA14_20750 | Unknown | Y | |||||||||||

| PA3462 | PA14_19340 | Unknown | Y | |||||||||||

| PA3704 | PA14_16470 | PA3702 | PA14_16500 | WspE–WspR | Surface-associated growth | Wsp chemosensory system. Regulates biofilm, autoaggregation and cyclic-di-GMP. WspR contains GGDEF output domain, WspE is CheA-type sensor | Y | Y | Y | D’Argenio et al. (2002); Hickman, Tifrea and Harwood (2005); Kulasekara et al. (2005); Borlee et al. (2010); Huangyutitham et al. (2013) | ||||

| PA3714 | PA14_16350 | Unknown | Y | |||||||||||

| PA3878 | PA14_13740 | PA3879 | PA14_13730 | NarX–NarL | Nitrate | Nitrate sensing and respiration. Biofilm formation, fermentation, swimming and swarming motility | Y | Y | Van Alst et al. (2007); Benkert et al. (2008) | |||||

| PA4032 | PA14_11680 | Y | ||||||||||||

| PA4036 | PA14_11630 | Unknown | Y | |||||||||||

| PA4080 | PA14_11120 | Unknown | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| PA4102 | PA4101 | BfmS-BfmR | Unknown | Biofilm formation/maintenance | Y | Y | Y | Petrova and Sauer (2009) | ||||||

| PA4112 | PA14_10770 | Unknown | Antibodies against this protein found in CF patient sera | Y | Y | Y | Beckmann et al. (2005) | |||||||

| PA4293 | PA14_55780 | PA4296 | PA14_55810 | PprA–PprB | Unknown | Outer membrane permeability and aminoglycoside resistance. Virulence including T3 secretion and biofilm formation | Y | Y | Y | Wang et al. (2003); Giraud et al. (2011); de Bentzmann et al. (2012) | ||||

| PA4398 | PA14_57170 | PA4396 | PA14_57140 | Unknown | Overexpression impairs T3 secretion-mediated cytotoxicity. GGDEF output domain. In PA14, PA4398 sensor kinase regulates motility and biofilm. PA14_57170 is essential in PA14 | Y | Y | Kulasakara et al. (2006); Strehmel et al. (2015) | ||||||

| PA4494 | PA14_58320 | PA4493 | PA14_58300 | RoxS-RoxR | Possibly cyanide | Cyanide tolerance. Neutrophil transmigration response | Y | Y | Y | Comolli and Donohue (2002); Hurley et al. (2010); Fernández-Piñar et al. (2012) | ||||

| PA4546 | PA14_60250 | PA4547 | PA14_60260 | PilS–PilR | Pilin subunits | Biofilm formation, type IV pilus expression, twitching and swarming motility | Y | Y | Y | Y | Ishimoto and Lory (1992); Hobbs et al. (1993); Overhage et al. (2007); Kilmury and Burrows (2016) | |||

| PA4725 | PA14_62530 | PA4726 | PA14_62540 | CbrA–CbrB | Various carbon sources | Carbon and nitrogen storage, cytotoxicity, swarming motility, modulates metabolism, virulence and antibiotic resistance in PA14 | Y | Y | Y | Gallagher and Manoil (2001); Rietsch, Wolfgang and Mekalanos (2004); Wagner et al. (2007); Yeung, Bains and Hancock (2011); Yeung et al. (2014) | ||||

| PA4781 | PA14_63210 | Unknown | Y | |||||||||||

| PA4886 | PA14_64580 | PA4885 | PA14_64570 | IrlR | Unknown | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||||

| PA4959 | PA14_65540 | FimX | Unknown | Phosphodiesterase (GGDEF and EAL domains). Signal transduction protein involved in twitching motility phosphotransfer activity, and cyclic di-GMP metabolism. Reduced in vitro cytotoxicity | Huang, Whitchurch and Mattick (2003); Kazmierczak, Lebron and Murray (2006); Kulasakara et al. (2006); Jain et al. (2012) | |||||||||

| PA4982 | PA14_65860 | PA4983 | PA14_65880 | AruS-AruR | Arginine | Antibodies against this protein found in CF patient sera. Controls expression of the arginine transaminase pathway | Y | Beckmann et al. (2005); Yang and Lu (2007) | ||||||

| PA5124 | PA14_67670 | PA5125 | PA14_67680 | NtrB-NtrC | PII—nitrogen status | Responds to cellular nitrogen levels and activates nitrogen scavenging genes | Y | Y | Y | Li and Lu (2007) | ||||

| PA5165 | PA14_68230 | PA5166 | PA14_68250 | DctB-DctD | C4-dicarboxylates | Controls expression of C4-dicarboxylate transporters | Y | Y | Y | Y | Valentini, Storelli and Lapouge (2011) | |||

| PA5199 | PA14_68680 | PA5200 | PA14_68700 | AmgS-AmgR | Aminoglycosides | Aminoglycoside resistance and cell envelope stress response. Described as essential in PA14 | Y | Y | Y | Lau et al. (2013, 2015) | ||||

| PA5364 | PA14_70790 | Unknown | Y | |||||||||||

| PA5484 | PA14_72390 | PA5483 | PA14_72380 | KinA-AlgB | Unknown | Alginate biosynthesis. Virulence, acute/chronic switch | Y | Y | Y | Leech et al. (2008); Chand et al. (2011); Chand, Clatworthy and Hung (2012) | ||||

| PA5512 | PA14_72740 | PA5511 | PA14_72720 | MifS-MifR | α-Ketoglutarate | Biofilm formation and metabolism | Y | Tatke et al. (2015) | ||||||

The TCSs known to form multikinase networks are listed in the first section and the others are listed in the second section. The columns to the right of the description column refer to whole genome studies investigating virulence using the following methodologies: Tn-Seq, signature tagged mutagenesis, and the study of pathoadaptive mutations in CF patient isolates. ‘Y’ indicates that the study has implicated the TCS in virulence.

Highlights the five multikinase networks that are discussed in depth in this minireview.

TCSs are generally considered to work alone, sensing either a single stimulus or a narrow range of stimuli to control appropriate responses, being insulated from significant crosstalk (Laub and Goulian 2007; Capra et al.2012), with relatively few exceptions (Willett and Crosson 2017). However, a recently emerging theme, in which tremendous progress has been made in the last few years, is the discovery that multikinase networks play leading roles in orchestrating the virulence of P. aeruginosa. Multikinase networks comprise multiple SKs that collaborate to form sophisticated networks capable of sensing and integrating multiple stimuli. In the following sections, we explore how these networks regulate virulence.

THE TRANSITION BETWEEN ACUTE AND CHRONIC MODES OF INFECTION: THE GacS NETWORK

The GacS network plays a leading role in governing the transition between acute and chronic modes of infection. It has emerged as a prime example of a multikinase network, where multiple SKs work together to detect and integrate several different signals to reach a balanced decision. The central kinase in this network, GacS, controls the phosphorylation of the RR, GacA (Fig. 1). Phosphorylated GacA activates the transcription of two non-coding RNAs, RsmY and RsmZ, and they bind and sequester the translational regulators, RsmA (Brencic et al.2009) and the more recently discovered RsmN (Morris Elizabeth et al.2013). Free RsmA and RsmN bind to certain mRNAs, promoting the degradation of transcripts involved in chronic virulence (e.g. relating to biofilm formation, T6SS and extracellular products such as pyocyanin and cyanide) while favouring those involved in acute infection (e.g. relating to T3SS and motility) (Reimmann et al. 1997; Parkins, Ceri and Storey 2001; Pessi et al.2001; Valverde et al.2003; Heurlier et al.2004; Burrowes et al.2006; Mulcahy et al. 2008; Brencic and Lory 2009; Moscoso et al.2011; Morris Elizabeth et al.2013). In short, when GacS signalling is active, GacA will be phosphorylated and this will favour the chronic mode of infection.

Figure 1.

The GacS network including the closely affiliated HptB and SagS/BfiS branches. Red ovals show SKs, blue ovals show RRs, the purple oval shows the HptB protein and the grey ovals show other proteins in the system. Arrows show stimulatory interactions, while blunt-ended lines show inhibitory interactions and bulb-ended lines show interactions that can be stimulatory or inhibitory depending on conditions. The primary output of the GacS side of the pathway is the small RNAs RsmY and RsmZ, which sequester the post-transcriptional regulators, RsmA and RsmN. When RsmA and RsmN are sequestered, virulence genes associated with chronic infection are upregulated while those associated with acute virulence genes are downregulated. Conversely, when RsmA and RsmN are free, the acute virulence genes are upregulated and the chronic infection genes are downregulated. The HptB and SagS/BfiS branches of the pathway also regulate RsmY and RsmZ levels, respectively. The role of HsbA differs depending on whether it is phosphorylated (blue arrow) or dephosphorylated (red arrow). Two diguanylate cyclases are controlled by this network, HsbD and SadC.

GacS is an unorthodox kinase (containing HisKA, HATPase, REC and Hpt domains) whose signalling activity is controlled through kinase–kinase interactions by three hybrid SKs: RetS, LadS and PA1611. RetS and LadS interact with GacS, with RetS inhibiting, and LadS activating, GacS signalling (Goodman et al.2004; Laskowski, Osborn and Kazmierczak 2004; Laskowski and Kazmierczak 2006; Ventre et al.2006). RetS downregulates GacS signalling by binding to GacS and reducing its ability to autophosphorylate (Goodman et al.2009), whereas LadS upregulates GacS signalling through a phosphorelay mechanism where phosphoryl groups are transferred from the REC domain of LadS to the Hpt domain of GacS (Chambonnier et al.2016). Unlike RetS and LadS, PA1611 does not interact with GacS; instead, PA1611 binds to RetS, which prevents it from inhibiting GacS (Kong et al.2013; Bhagirath et al.2017). The interaction of the four SKs allows for the integration of signals to modulate GacS phosphorylation levels and therefore, the output of the pathway. The signals that activate the various SKs are largely unidentified. However, GacS and RetS are controlled by molecules produced at high cell density and during the lysis of kin cells, respectively, although the identity of these molecules remains elusive (Heeb, Blumer and Haas 2002; LeRoux et al.2015). Recently, it has been shown that LadS from P. aeruginosa is activated by calcium ions to upregulate chronic phenotypes (Broder, Jaeger and Jenal 2016).

The importance of the GacS network has been demonstrated using infection models, with Tn-Seq studies finding that most components of the network are required in either acute and/or chronic virulence in mice (Turner et al.2014). Moreover, isolates from CF patients often have pathoadaptive mutations within GacS network components, indicating that fine-tuning the signalling of the network can facilitate long-term colonisation and bacterial survival (Cramer et al.2011; Marvig et al.2015). Interestingly, strain PA14, which was originally isolated from a burn wound, has a frameshift mutation in ladS. Relative to many other strains, PA14 shows enhanced acute virulence, which can, in part, be attributed to the mutation in ladS (Mikkelsen, McMullan and Filloux 2011). Another clinical isolate, CHA, has a deletion in gacS and exhibits enhanced acute virulence phenotypes (Sall et al.2014). These studies show the importance of this network in infection and how environmental pressures can reshape the virulence of P. aeruginosa by mutationally fine-tuning this network.

The HptB branch of the GacS network

Two of the SKs that form part of the core of the GacS network, RetS and PA1611 (described above), also interact with HptB and together form the HptB branch of the GacS network along with two further hybrid SKs, SagS and ErcS’ (Lin et al.2006; Hsu et al.2008). HptB is a histidine phosphotransfer protein (Hpt) that serves in a phosphorelay connecting RetS, PA1611, SagS and ErcS’ with an unusual output RR, HsbR (PA3346). HsbR has an N-terminal REC domain, a protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C)-like domain and a C-terminal ser/thr kinase domain (Hsu et al.2008; Bhuwan et al.2012). When phosphorylated, HsbR acts as a phosphatase to dephosphorylate the anti-anti sigma factor, HsbA (PA3347). Dephosphorylated HsbA (red arrow, Fig. 1) then sequesters the anti-sigma factor FlgM, which is otherwise found in a complex with the sigma factor, FliA. Free FliA promotes expression of the flagellar genes and therefore both swimming and swarming motility (Bhuwan et al.2012).

When HptB is inactive (i.e. not phosphorylated or absent), the receiver domain of HsbR dephosphorylates, which causes the ser/thr kinase domain of HsbR to be more active than its phosphatase domain. Consequently, HsbR phosphorylates HsbA, preventing it from binding and sequestering FlgM. FlgM instead binds FliA and this leads to a decreased expression of the flagellar genes. Furthermore, phosphorylated HsbA (blue arrow, Fig. 1) is thought to bind to, and activate, the diguanylate cyclase HsbD, which leads to an increase in c-di-GMP and RsmY levels (Bordi et al.2010; Valentini et al.2016). How exactly HsbD modulates RsmY levels is not known, but it is known that the upregulation of rsmY expression in the ΔhptB mutant depends upon intact GacS/GacA signalling (Bordi et al.2010; Jean-Pierre, Tremblay and Deziel 2017).

The SagS/BfiS branch of the GacS network

SagS is involved in the motile-sessile switch and resistance to antimicrobials (Petrova and Sauer 2011; Petrova et al.2017), and as well as being one of the SKs that can phosphorylate HptB (Petrova and Sauer 2011), SagS has a HptB independent signalling route. SagS regulates both RsmY and RsmZ through distinct pathways; its regulation of RsmY is HptB dependent (Bordi et al.2010; Petrova and Sauer 2011), while its regulation of RsmZ is HptB independent and involves an interaction with another SK, BfiS. BfiS is required for the transition to irreversible attachment of cells during biofilm formation. The interaction between SagS and BfiS relies upon the conserved phosphorylation sites of these SKs (Petrova and Sauer 2010, 2011). The cognate RR of BfiS, BfiR, activates expression of CafA (RNase G). CafA reduces the level of RsmZ, which is required for maturation and maintenance of biofilms (Petrova and Sauer 2010). The SagS/BfiS branch of the network, therefore, regulates the level of RsmZ post-transcriptionally, while the rest of the GacS network regulates both RsmY and RsmZ at the transcriptional level (Ventre et al.2006; Goodman et al.2009). RsmY and RsmZ levels can also be influenced by other regulators such as Anr/NarL, which downregulates both sRNAs under conditions of low oxygen, and the β-lactamase regulator, AmpR, which can upregulate RsmZ (O’Callaghan et al.2011; Balasubramanian, Kumari and Mathee 2015). It appears that levels of these sRNAs are tightly coordinated by multiple intersecting regulators to orchestrate the transition from acute to chronic virulence and the planktonic to biofilm mode of growth.

The GacS network produces and responds to c-di-GMP

Two major ways that the GacS network is known to affect c-di-GMP levels are, first, that RsmA controls the translation of the sadC mRNA, which encodes the diguanylate cyclase, SadC (Moscoso et al.2014), and second, the HptB branch of the GacS network regulates the HsbD diguanylate cyclase (Valentini et al.2016). Intriguingly, in addition to controlling c-di-GMP levels, the GacS network appears to respond to c-di-GMP levels. Overexpressing diguanylate cyclases can induce the T3SS (acute) to T6SS (chronic) switch, and this is dependent upon the regulatory RNAs, RsmY and RsmZ (Moscoso et al.2011). RsmY and RsmZ levels have also been shown to be elevated in strains overexpressing diguanylate cyclases (Frangipani et al.2014). It is therefore tempting to speculate that increased c-di-GMP levels activate signalling within the GacS network to help promote biofilm formation and the chronic mode of virulence. In line with this, it has recently been shown that the PilZ domain protein, HapZ, can bind to SagS and inhibit phosphotransfer to HptB, in a c-di-GMP-dependent manner (Xu et al.2016). In addition, it is possible that c-di-GMP affects signalling elsewhere in the network in yet to be determined ways.

In summary, the GacS network is a complex multikinase network that plays a major role in deciding between acute and chronic modes of virulence, and between planktonic and biofilm modes of growth. The complexity of the network and the large number of different sensors is likely to reflect the importance of making the correct decision to the survival of the bacterium, and the need to evaluate numerous signals (e.g. Ca2+, kin-cell lysis, c-di-GMP plus several other as yet unidentified signals) in order to inform this decision.

CONTROL OF CUP FIMBRIAE PRODUCTION: THE ROC NETWORK AND RCS/PVR NETWORK

Surface adhesins, known as Cup fimbriae (chaperone/usher pili), are required for the initial attachment stage of biofilm formation. Pseudomonas aeruginosa has three different sets of archetypal Cup fimbriae genes in its core genome (cupA, cupB and cupC). The PA14 strain has an extra set of fimbriae genes, cupD, within the PAPI-I pathogenicity island. The cupB and cupC genes are controlled by the Roc network, while the cupD genes of PA14 are regulated by the Rcs/Pvr network (Kulasekara et al.2005; Rao et al.2008; Mikkelsen et al.2009, 2013). In addition to regulating the CupB and CupC fimbriae, the Roc network also controls expression of the MexAB-OprM drug efflux pump (Sivaneson et al.2011).

Like the GacS network, the Roc network is another good example of a multikinase network, and again c-di-GMP signalling is involved, but unlike the GacS network, which is built from kinase–kinase interactions, the Roc network is instead based upon SKs sharing the same RRs (Fig. 2A). This network comprises two SKs—RocS1 and RocS2, which are both unorthodox (having HisKA, HATPase, REC and Hpt domains)—that control at least three RRs: RocA1 (helix-turn-helix DNA binding output domain), RocR (EAL, c-di-GMP degrading, phosphodiesterase output domain) and RocA2 (helix-turn-helix DNA-binding output domain). Each of the two SKs is capable of interacting with each of the RRs. The RRs target different genes: RocA1 activates expression of the CupC fimbriae, RocA2 inhibits expression of the MexAB-OprM drug efflux pump, and RocR by reducing c-di-GMP levels reduces expression of both cupB and cupC fimbriae genes. There is good reason to believe that an additional RR is involved in this network as the two SKs, RocS1 and RocS2, promote expression of CupB fimbriae genes in a manner independent of any of the three known RRs (Kulasekara et al.2005; Rao et al.2008; Sivaneson et al.2011). Although the controlling stimuli are unknown for the Roc network, the cross-regulation within this network should allow multiple inputs to be evaluated and for these signals to be integrated.

Figure 2.

Model of the Roc network (A) and Rcs/Pvr network (B). Red ovals indicate the SKs, while the blue ovals are the RRs. The green oval is the unknown component that regulates cupB fimbriae. Arrows specify positive interactions and blunt-ended lines show inhibitory interactions. The bulb-ended line indicates that RcsC can have either stimulatory or inhibitory effects on RcsB depending on conditions.

Roc network signalling promotes adhesion and therefore biofilm formation, while reducing expression of the MexAB-OprM antibiotic efflux pump. Initially, this seems counterintuitive, as biofilms are usually associated with increased antibiotic resistance. However, reduced expression of mexAB-oprM is seen in mature biofilms, and strains isolated from CF patients often show inactivation of this efflux pump despite having a high propensity for biofilm formation (De Kievit et al.2001; Vettoretti et al.2009). This suggests that the MexAB-OprB drug efflux pump is not involved in the antibiotic resistance of biofilms.

The cupD cluster, found in strain PA14, is regulated by an orthologous system to the Roc network consisting of two SKs, RcsC (unorthodox) and PvrS (hybrid), and two RRs, RcsB and PvrR (Fig. 2B). Like the Roc system, RcsB has a HTH DNA-binding domain, while PvrR has an EAL output domain. Interestingly, in this system, PvrS appears to act as a kinase, while RcsC functions primarily as a phosphatase and also acts in an intermolecular phosphorelay connecting PvrS with the output RRs. In this phosphorelay, phosphoryl groups are passed from the REC domain of the hybrid SK, PvrS, to the Hpt domain of RcsC and from there onto the REC domains of the output RRs. This kinase–kinase phosphorelay mode of interaction is reminiscent of the GacS/LadS interaction in the GacS network and is likely to represent a conserved signalling route where the Hpt domain of an unorthodox kinase is used to connect hybrid kinases (that lack Hpt domains) with their output RRs (Mikkelsen et al.2009, 2013; Chambonnier et al.2016).

THE REGULATORY NETWORK CONTROLLING THE AMINOARABINOSE MODIFICATION OF LIPOPOLYSACCHARIDE

During infection, Pseudomonas aeruginosa needs to evade host defences such as cationic antimicrobial peptides, and to resist any antibiotic treatments that the patient may be receiving. One major way that this can be achieved is by inducing the aminoarabinose modification of the lipid A component of the lipopolysaccharide layer. This modification reduces the negative charge on the LPS, thereby limiting its electrostatic interaction with, and the subsequent uptake of, cationic antimicrobial peptides and cationic lipopeptide antibiotics (including polymyxins such as colistin, which are often used as last-resort antibiotics in CF patients). The genes required for the modification are encoded by the arnBCADTEF operon and it is regulated by a sensory network comprising at least five distinct TCSs each comprising a SK and a RR: PhoQP, PmrBA, ColSR, CprSR and ParSA (Macfarlane et al.1999; Macfarlane, Kwasnicka and Hancock 2000; McPhee, Lewenza and Hancock 2003; Moskowitz, Ernst and Miller 2004; Gooderham and Hancock 2009; Gooderham et al.2009; Fernández et al.2010, 2012; Gutu et al.2013; Lee and Ko 2014).

Unlike the GacS and Roc networks, there is no documented linkage at the phosphosignalling level between these TCSs, instead the output RRs of the separate TCSs converge upon the aminoarabinose modification genes (Fig. 3), as a common feature of each RR's unique wider regulon. The SKs, PhoQ and PmrB, are active when the Mg2+ concentration is low (McPhee et al.2006), while the SKs, CprS and ParS, are activated by different cationic antimicrobial peptides (Fernández et al.2010, 2012; Muller, Plésiat and Jeannot 2011), and ColS is activated by Zn2+ (Nowicki et al.2015). Extracellular DNA is a significant component of the biofilm matrix and is often found at infection sites, and it appears to play an important physiological role in the PhoQP and PmrBA responses, as it sequesters cations and can reduce Mg2+ levels to the extent that PhoQ and PmrB signalling are activated, thereby promoting LPS modification and increasing resistance to host cationic peptides and polymyxins (Mulcahy, Charron-Mazenod and Lewenza 2008; Gellatly et al.2012; Lewenza 2013).

Figure 3.

The network controlling the aminoarabinose modification of lipid A component of lipopolysaccharide. Five TCSs work together to sense magnesium ions, zinc ions and cationic antimicrobial peptides to regulate the expression of the arnBCADTEF operon which encodes the LPS modification enzymes. The LPS modification enhances resistance to host-derived cationic antimicrobial peptides and to polymyxin antibiotics.

This regulatory network undergoes strong selective pressures in CF patients and adaptive mutations are frequently identified in isolates from CF patients, particularly those who have been treated with polymyxins. These mutations can be in any of the TCSs of this network although mutations affecting PhoQP and PmrBA are particularly common; generally, they lead to either increased or constitutive expression of the genes for the aminoarabinose modification, and are frequently accompanied by other mutations in non-TCS genes (such as those for LPS biogenesis and outer membrane protein assembly) that further boost resistance levels (Barrow and Kwon 2009; Fernández et al.2010; Miller et al.2011; Gellatly et al.2012; Moskowitz et al.2012; Gutu et al.2013; Jochumsen et al.2016).

SURFACE SENSING: THE WSP CHEMOSENSORY PATHWAY

One way that Pseudomonas aeruginosa responds to growth on surfaces is by activating the Wsp chemosensory system. This pathway controls the production of the secondary messenger, c-di-GMP, which promotes biofilm formation and decreases expression of the flagellar genes. Like the Chp chemosensory system (below), the Wsp chemosensory system forms a signal transduction system (Fig. 4) resembling the bacterial chemotaxis system (He and Bauer 2014). The Wsp pathway incorporates the cytoplasmic SK, WspE, which phosphorylates two RRs, the methylesterase, WspF, and the diguanylate cyclase, WspR (Bantinaki et al.2007). Surface growth is sensed by the membrane-bound WspA protein (a methyl-accepting-chemotaxis protein homologue), possibly via mechanical sensing of physical pressure resulting from surface association and cell–cell contact (O’Connor et al.2012). Contact sensing by WspA triggers autophosphorylation of WspE, which in turn phosphorylates and activates WspR and WspF. WspR-P catalyses the production of c-di-GMP through its GGDEF domain (Bantinaki et al.2007; De et al.2008, 2009). When WspR is dephosphorylated, it is delocalised within the cytoplasm, but when phosphorylated, it aggregates to form cytoplasmic clusters (Guvener and Harwood 2007), where its diguanylate cyclase activity is increased (Huangyutitham et al.2013). WspF-P acts to reset the system by removing methyl groups from WspA (Hickman, Tifrea and Harwood 2005; Bantinaki et al.2007). Deletion of wspF results in constitutive activation of WspR (WspR-P) due to overmethylation of WspA and produces a distinctive wrinkled, small colony phenotype with enhanced biofilm formation (Hickman, Tifrea and Harwood 2005).

Figure 4.

The Wsp chemosensory pathway. The proteins involved in the pathway are a methyl-accepting protein (WspA), CheW homologues (WspB and WspD), a CheA homologue (WspE), a diguanylate cyclase RR (WspR), a methylesterase RR (WspF) and a methyltransferase (WspC). Mechanical pressure associated with surface growth activates WspA, which promotes the autophosphorylation of WspE. WspE phosphorylates its two RRs, WspR and WspF. Phosphorylated WspR catalyses the synthesis of c-di-GMP (the secondary messenger output of this system). Meanwhile, phosphorylated WspF acts to reset the system by removing methyl groups from WspA, reducing its ability to activate WspE. The methylesterase activity of WspF is opposed by the constitutive methyltransferase activity of WspC.

Activation of the Wsp pathway by surface sensing triggers an increase in c-di-GMP levels (Hickman, Tifrea and Harwood 2005; O’Connor et al.2012; Ha and O’Toole 2015). The transcriptional regulator, FleQ, is the major target for the c-di-GMP produced by the Wsp pathway. FleQ promotes expression of the flagellar genes and downregulates biofilm-associated genes (e.g. pel encoding exopolysaccharide biosynthesis proteins). FleQ is inhibited by binding c-di-GMP, and therefore Wsp pathway activation leads to reduced expression of the flagellar genes and increased expression of biofilm-associated genes (Hickman, Tifrea and Harwood 2005; Hickman and Harwood 2008).

Consistent with its role in promoting biofilm formation, Tn-Seq data has shown that the Wsp pathway is required for chronic wound infections in mice (Turner et al.2014). Moreover, isolates from CF patients often show pathoadaptive mutations in the Wsp pathway (Marvig et al.2015); wspF mutations being particularly common with their distinctive phenotype of having a rugose appearance and enhanced biofilm formation (D’Argenio et al.2002; Hickman, Tifrea and Harwood 2005; Smith et al.2006; Starkey et al.2009; Sousa and Pereira 2014; Blanka et al.2015). This indicates that the Wsp pathway is under selective pressures to affect its signalling output during long-term infection, with constitutive activation being favourable for biofilm growth and chronic infection.

SURFACE SENSING: THE CHP/FIMS/ALGR NETWORK

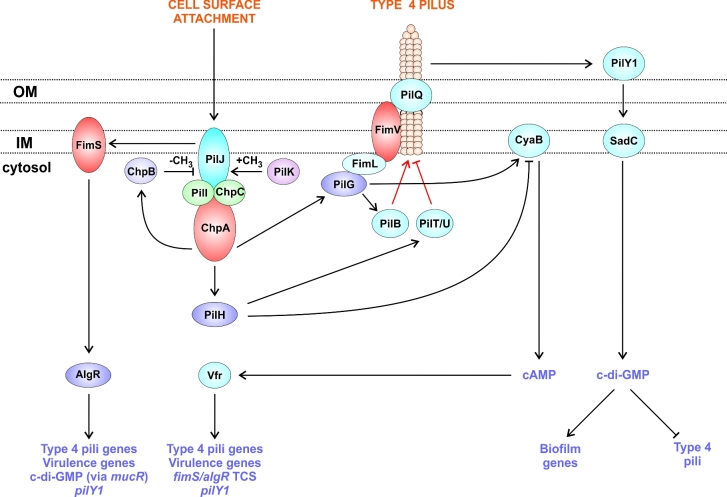

The Wsp pathway and the Chp/FimS/AlgR network are distinct but have many similarities; both sense surface contact, both involve a chemosensory pathway, both use secondary messenger signalling and, like many other signalling networks, both contribute to biofilm formation. In that sense they can be considered to form a super network (O’Toole and Wong 2016). The Chp/FimS/AlgR network is itself an example of a multikinase network. It regulates production of two different secondary messengers, cAMP and c-di-GMP, to control virulence and biofilm formation (Fig. 5). The production and activity of type 4 pili (T4P) are also controlled by this network and, moreover, they play a central signalling role. T4P are major surface adhesins allowing adherence and invasion of host tissues (Hahn 1997). They are located at the cell poles and undergo repeated cycles of extension, adhesion and retraction to pull the cell forward in a process called twitching motility (Skerker and Berg 2001; Mattick 2002). The extension and retraction of these pili are controlled by the Chp chemosensory pathway part of the Chp/FimS/AlgR network, which also controls levels of the secondary messenger, cyclic AMP (cAMP) (Darzins 1994; Whitchurch et al.2004; Fulcher et al.2010). cAMP regulates many other cellular processes and genes, primarily via the transcription factor Vfr (virulence factor regulator) which upregulates many virulence genes, including those involved with quorum sensing, type 2 secretion, T3SS, the FimS/AlgR TCS and the T4P themselves (Albus et al.1997; Wolfgang et al.2003; Kanack et al.2006; Bertrand, West and Engel 2010; Fulcher et al.2010).

Figure 5.

The Chp/FimS/AlgR network controls the production and operation of the type 4 pili, involved in surface attachment and twitching motility, and the expression of virulence genes. Surface contact is detected by PilJ (an MCP homologue), it activates signalling by two SKs: ChpA (a CheA homologue) and FimS. FimS phosphorylates its RR, AlgR, leading to the activation of its regulon (T4P genes, virulence genes, the diguanylate cyclase gene mucR and pilY1). ChpA phosphorylates three RRs: ChpB (a CheB homologue that mediates adaptation), PilG which activates the adenylate cyclase (CyaB) and the pilus extension ATPase (PilB), and PilH which may activate the pilus retraction ATPases (PilT/U) and inhibit adenylate cyclase (CyaB). The cAMP produced by CyaB binds to and activates the transcription factor Vfr, leading to the activation of its vast regulon, which includes T4P genes, virulence genes, the fimS/algR TCS and pilY1. After prolonged surface contact, the number of T4P increases due to AlgR and Vfr activity, which promotes the secretion of the outer-membrane surface-associated PilY1 protein. PilY1 signals to the diguanylate cyclase, SadC, which produces c-di-GMP that leads to the upregulation of biofilm genes and the downregulation of the T4P.

The Chp chemosensory pathway resembles, but is distinct from, the chemotaxis pathway regulating flagellar rotation. It uses a methyl-accepting-chemotaxis-protein (MCP) homologue, PilJ, to detect surface contact and chemoattractants such as phosphatidylethanolamine (Kearns, Robinson and Shimkets 2001; Jansari et al.2016). Sensing of surface contact involves mechanosensing, where PilJ is thought to respond to tension generated within the pili, when the cell retracts pili that have adhered to surfaces (Persat et al.2015). The signal from PilJ is relayed via two adaptor proteins, PilI and ChpC, to an unorthodox SK, ChpA. ChpA is one of the most complex SKs found in any bacterial species, having nine potential phosphorylation sites; it has eight ‘Xpt’ domains, six of which are conventional Hpt domains and two that contain either serine or threonine in place of the usual phosphorylatable histidine, plus a receiver domain (ChpArec) (Whitchurch et al.2004; Leech and Mattick 2006). ChpA autophosphorylates on Hpt domains 4–6 and phosphotransfer occurs from Hpts 5 and 6 to ChpArec, but also, at a slower rate, to two standalone RRs: PilG and PilH. Reversible phosphotransfer can occur from ChpArec to Hpt 2–6; however, as yet, no phosphorylation has been observed on Hpt 1 or the remaining two ‘Xpt’ domains (Silversmith et al.2016). Hpt 2 and Hpt 3 serve as the main phosphodonors to the two output RRs, PilG and PilH (Hpt5 and 6 also contribute but at a much slower rate), that control the adenylate cyclase, CyaB (Wolfgang et al.2003; Fulcher et al.2010; Silversmith et al.2016), and the pilus extension (PilB) and retraction (PilT/U) ATPases (Bertrand, West and Engel 2010).

The RR, PilG, localises to the cell poles along with the pili forming a complex with FimL and FimV; presumably this helps to keep its local concentration high, proximal to its kinase, ChpA (Inclan et al.2016). The details of how PilG and PilH regulate adenylate cyclase and the pilus ATPases are not known, although models have been proposed based on genetic studies, where PilG stimulates pilus extension (via PilB) and CyaB activity, as the ΔpilG mutant has reduced piliation and reduced cAMP levels, while PilH stimulates pilus retraction (via PilT/U) and inhibits CyaB activity, as the ΔpilF mutant has increased piliation and increased cAMP (Bertrand, West and Engel 2010; Fulcher et al.2010). The role of PilH is controversial though, and instead it might function as a phosphate sink for PilG rather than directly regulating CyaB and PilT/U.

The Chp chemosensory pathway associates with the FimS/AlgR TCS (also known as AlgZ/R) to form the Chp/FimS/AlgR multikinase network. This network is constructed differently from the other examples of multikinase network discussed; here, the two SKs, FimS and ChpA, do not interact directly but instead they interact with a common partner, the MCP homologue, PilJ. FimS is thought to be activated by surface contact, and an attractive model would be for the surface contact sensor, PilJ, to control FimS activity via their interaction (Luo et al.2015). The FimS/AlgR TCS is best known for its role in controlling the production of the exopolysaccharide, alginate, but it is also required for twitching motility as it regulates expression of the T4P, and is involved in multiple other pathways including hydrogen cyanide and rhamnolipid production, T3SS, the Rhl quorum-sensing system and biofilm formation (Whitchurch, Alm and Mattick 1996; Okkotsu, Little and Schurr 2014).

The role of cAMP as the initial secondary messenger in the Chp/FimS/AlgR network is well known, with the Chp chemosensory system producing cAMP in response to surface contact, which activates Vfr, leading to activation of the expression of many virulence genes including the FimS/AlgR TCS. However, recently, c-di-GMP has been implicated as a delayed secondary messenger from this network (Fig. 5) i.e. following activation by surface contact, cAMP is produced initially and then several hours later c-di-GMP is produced, correlating with the onset of biofilm formation (O’Toole and Wong 2016). Two diguanylate cyclases are involved, SadC (which is also controlled by the GacS network) and MucR, with one of the targets for the c-di-GMP that they produce being the c-di-GMP binding protein, Alg44, which stimulates alginate production (Hay, Remminghorst and Rehm 2009; Schmidt et al.2016). MucR expression is stimulated by AlgR when the network senses surface contact (Kong et al.2015). Regulation of SadC is more complex; AlgR and Vfr together upregulate the fimU-pilVWXXY1Y2E operon, which is necessary for T4P biogenesis and function (Luo et al.2015). PilY1, encoded by this operon, is a cell-surface-associated protein that promotes the activity of SadC and downregulates swarming motility (Kuchma et al.2010). Crucially, PilY1 depends upon the T4P for export ensuring an ordered signalling cascade where pili are made first, before PilY1 is deployed and c-di-GMP production initiated (Luo et al.2015).

CONCLUSIONS

TCSs play a major role in controlling Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence, with over 50% of its TCSs implicated in controlling either virulence or virulence-related behaviours such as biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance (Table 1). A theme highlighted by the above examples is that during infection, P. aeruginosa makes extensive use of multikinase networks to detect and integrate multiple environmental signals, and to reach a balanced decision about the most appropriate response. There are a multitude of different architectures for these multikinase networks:

Kinase–kinase interaction. Seen in the GacS network (Fig. 1) and the Rcs/Pvr network (Fig. 2B).

Multiple SKs can share the same RR(s), as in the Roc network (Fig. 2A) and in the HptB branch of the GacS network (Fig. 1).

Connector proteins can link the SKs e.g. in the Chp/FimS/AlgR network, the surface contact sensing MCP homologue, PilJ, interacts with two SKs, ChpA and FimS (Fig. 5).

Regulatory convergence between TCSs, where otherwise separate TCSs control the expression of the same genes, as seen in the network controlling LPS modification (Fig. 3).

Transcriptional control of one TCS by another TCS e.g. in the Chp/FimS/AlgR system, the expression of the FimS/AlgR TCS is induced by Vfr, which is activated by binding cAMP that is produced by CyaB due to signalling by the ChpA SK (Fig. 5).

A further finding is that these regulatory networks undergo considerable selective pressure within hosts, particularly during chronic infection and it is common to isolate mutant strains with pathoadaptive mutations in these networks e.g. showing enhanced biofilm formation, increased antibiotic resistance or reduced motility (Marvig et al.2013, 2015; Jochumsen et al.2016; Winstanley, O’Brien and Brockhurst 2016). This shows that while the wild-type regulatory networks may be capable of efficiently orchestrating virulence across a broad range of conditions, there are circumstances where the networks can be genetically fine-tuned to optimise behaviour to better suit the prevailing conditions e.g. chronic infection in the CF lung, although this often comes at expense of the bacterium's ability to thrive in other conditions e.g. at causing acute infections (Smith et al.2006; Jeukens et al.2014).

Another key theme illustrated by the above examples is the interplay between multikinase networks and secondary messenger systems, with several of the networks discussed modulating levels of c-di-GMP. This provides another level of signal integration and decision making as all of the signals from several, otherwise separate, networks can feed into these secondary messengers to control common outputs important for virulence such as biofilm formation and motility.

Key priorities for the future advancement of our understanding of these multikinase networks that could facilitate the development of new ways of targeting these networks and tackling infection are as follows:

The ligands controlling many of the TCSs discussed above remain unknown, and although some recent progress has been made in this area (e.g. Broder, Jaeger and Jenal 2016) we urgently need systematic high-throughput methods for ligand identification.

Determining which kinases work together in multikinase networks is a key priority. It is likely that many of the SKs in Table 1 will feature in yet to be discovered multikinase networks. A combination of biochemical, bioinformatic and genetic methods need to be employed for systematic screening for potential interactions.

Revealing the complex interfaces with other regulatory mechanisms i.e. secondary messenger signalling and one-component regulators, which frequently form integral parts of multikinase networks.

Understanding how multikinase networks process and integrate signals to make decisions. This will require a concerted effort employing mathematical modelling alongside a detailed biochemical understanding of the regulators involved, how they respond to signal, and their interactions and expression patterns.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council (MRC) [grant number MR/M020045/1], the Leverhulme Trust [grant number RPG-2014–228] and the RoseTrees Trust [grant number M328].

Conflict of interest. None declared.

REFERENCES

- Albus AM, Pesci EC, Runyen JL et al. Vfr controls quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 1997;179:3928–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian D, Kumari H, Mathee K. Pseudomonas aeruginosa AmpR: an acute–chronic switch regulator. Pathog Dis 2015;73:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bantinaki E, Kassen R, Knight CG et al. Adaptive divergence in experimental populations of Pseudomonas fluorescens. III. Mutational origins of wrinkly spreader diversity. Genetics 2007;176:441–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrow K, Kwon DH. Alterations in two-component regulatory systems of phoPQ and pmrAB are associated with polymyxin B resistance in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Ch 2009;53:5150–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin T, Zhang L, Hinz AJ et al. The biofilm-specific antibiotic resistance genendvB is important for expression of ethanol oxidation genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. J Bacteriol 2012;194:3128–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann C, Brittnacher M, Ernst R et al. Use of phage display to identify potentialPseudomonas aeruginosa gene products relevant to early cystic fibrosis airway infections. Infect Immun 2005;73:444–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benkert B, Quäck N, Schreiber K et al. Nitrate-responsive NarX-NarL represses arginine-mediated induction of thePseudomonas aeruginosa arginine fermentation arcDABC operon. Microbiology 2008;154:3053–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand JJ, West JT, Engel JN. Genetic analysis of the regulation of type IV pilus function by the Chp chemosensory system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 2010;192:994–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhagirath AY, Pydi SP, Li Y et al. Characterization of the direct interaction between hybrid sensor kinases PA1611 and RetS that controls biofilm formation and the type III secretion system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. ACS Infect Dis 2017;3:162–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhuwan M, Lee HJ, Peng HL et al. Histidine-containing phosphotransfer protein-B (HptB) regulates swarming motility through partner-switching system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 strain. J Biol Chem 2012;287:1903–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielecki P, Jensen V, Schulze W et al. Cross talk between the response regulators PhoB and TctD allows for the integration of diverse environmental signals in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nucleic Acids Res 2015;43:6413–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanka A, Düvel J, Dötsch A et al. Constitutive production of c-di-GMP is associated with mutations in a variant of Pseudomonas aeruginosa with altered membrane composition. Sci Signal 2015;8:ra36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blus-Kadosh I, Zilka A, Yerushalmi G et al. The effect of pstS and phoB on quorum sensing and swarming motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS One 2013;8:e74444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordi C, Lamy MC, Ventre I et al. Regulatory RNAs and the HptB/RetS signalling pathways fine-tune Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenesis. Mol Microbiol 2010;76:1427–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borlee BR, Goldman AD, Murakami K et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa uses a cyclic-di-GMP-regulated adhesin to reinforce the biofilm extracellular matrix. Mol Microbiol 2010;75:827–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brencic A, Lory S. Determination of the regulon and identification of novel mRNA targets of Pseudomonas aeruginosa RsmA. Mol Microbiol 2009;72:612–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brencic A, McFarland KA, McManus HR et al. The GacS/GacA signal transduction system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa acts exclusively through its control over the transcription of the RsmY and RsmZ regulatory small RNAs. Mol Microbiol 2009;73:434–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broder UN, Jaeger T, Jenal U. LadS is a calcium-responsive kinase that induces acute-to-chronic virulence switch inPseudomonas aeruginosa. Nat Microbiol 2016;2:16184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrowes E, Baysse C, Adams C et al. Influence of the regulatory protein RsmA on cellular functions in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, as revealed by transcriptome analysis. Microbiology 2006;152:405–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caille O, Rossier C, Perron K. A copper-activated two-component system interacts with zinc and imipenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 2007;189:4561–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capra EJ, Perchuk BS, Skerker JM et al. Adaptive mutations that prevent crosstalk enable the expansion of paralogous signaling protein families. Cell 2012;150:222–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambonnier GL, Roux LN, Redelberger D et al. The hybrid histidine kinase LadS Forms a multicomponent signal transduction system with the GacS/GacA two-component system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS Genet 2016;12:e1006032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chand NS, Clatworthy AE, Hung DT. The two-component sensor KinB acts as a phosphatase to regulate Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence. J Bacteriol 2012;194:6537–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chand NS, Lee JS-W, Clatworthy AE et al. The sensor kinase KinB regulates virulence in acute Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. J Bacteriol 2011;193:2989–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coggan KA, Wolfgang MC. Global regulatory pathways and cross-talk control Pseudomonas aeruginosa environmental lifestyle and virulence phenotype. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2012;14:47–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comolli JC, Donohue TJ. Pseudomonas aeruginosa RoxR, a response regulator related to Rhodobacter sphaeroides PrrA, activates expression of the cyanide-insensitive terminal oxidase. Mol Microbiol 2002;45:755–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer N, Klockgether J, Wrasman K et al. Microevolution of the major common Pseudomonas aeruginosa clones C and PA14 in cystic fibrosis lungs. Environ Microbiol 2011;13:1690–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Argenio DA, Calfee MW, Rainey PB et al. Autolysis and autoaggregation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa colony morphology mutants. J Bacteriol 2002;184:6481–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daddaoua A, Molina-Santiago C, la Torre JSD et al. GtrS and GltR form a two-component system: the central role of 2-ketogluconate in the expression of exotoxin A and glucose catabolic enzymes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nucleic Acids Res 2014;42:7654–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darzins A. Characterization of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa gene cluster Involved in pilus biosynthesis and twitching motility - sequence similarity to the chemotaxis proteins of enterics and the gliding bacterium Myxococcus xanthus. Mol Microbiol 1994;11:137–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darzins A, Russell MA. Molecular genetic analysis of type-4 pilus biogenesis and twitching motility using Pseudomonas aeruginosa as a model system–a review. Gene 1997;192:109–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta N, Wolfgang MC, Goodman AL et al. A four-tiered transcriptional regulatory circuit controls flagellar biogenesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 2003;50:809–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bentzmann S, Giraud C, Bernard CS et al. Unique biofilm signature, drug susceptibility and decreased virulence in Drosophila through the Pseudomonas aeruginosa two-component system PprAB. PLoS Pathog 2012;8:e1003052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Kievit TR, Parkins MD, Gillis RJ et al. Multidrug efflux pumps: expression patterns and contribution to antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Antimicrob Agents Ch 2001;45:1761–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De N, Navarro MVAS, Raghavan RV et al. Determinants for the activation and autoinhibition of the diguanylate cyclase response regulator WspR. J Mol Biol 2009;393:619–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De N, Pirruccello M, Krasteva PV et al. Phosphorylation-independent regulation of the diguanylate cyclase WspR. PLoS Biol 2008;6:e67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean CR, Neshat S, Poole K. PfeR, an enterobactin-responsive activator of ferric enterobactin receptor gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 1996;178:5361–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieppois G, Ducret V, Caille O et al. The transcriptional regulator CzcR modulates antibiotic resistance and quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS One 2012;7:e38148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y-H, Zhang X-F, An S-W et al. A novel two-component system BqsS-BqsR modulates quorum sensing-dependent biofilm decay in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Commun Integr Biol 2008;1:88–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenkard E, Ausubel FM. Pseudomonas biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance are linked to phenotypic variation. Nature 2002;416:740–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll JA, Brody SL, Kollef MH. The epidemiology, pathogenesis and treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Drugs 2007;67:351–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst RK, Yi EC, Guo L et al. Specific lipopolysaccharide found in cystic fibrosis airway Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Science 1999;286:1561–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure LM, Llamas MA, Bastiaansen KC et al. Phosphate starvation relayed by PhoB activates the expression of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa σVreI ECF factor and its target genes. Microbiology 2013;159:1315–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Piñar R, Espinosa-Urgel M, Dubern J-F et al. Fatty acid-mediated signalling between two Pseudomonas species. Environ Microbiol Rep 2012;4:417–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández L, Gooderham WJ, Bains M et al. Adaptive resistance to the “last hope” antibiotics polymyxin B and colistin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is mediated by the novel two-component regulatory system ParR-ParS. Antimicrob Agents Ch 2010;54:3372–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández L, Jenssen H, Bains M et al. The two-component system CprRS senses cationic peptides and triggers adaptive resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa independently of ParRS. Antimicrob Agents Ch 2012;56:6212–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frangipani E, Visaggio D, Heeb S et al. The Gac/Rsm and cyclic-di-GMP signalling networks coordinately regulate iron uptake in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ Microbiol 2014;16:676–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulcher NB, Holliday PM, Klem E et al. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa Chp chemosensory system regulates intracellular cAMP levels by modulating adenylate cyclase activity. Mol Microbiol 2010;76:889–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher LA, Manoil C. Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 kills Caenorhabditis elegans by cyanide poisoning. J Bacteriol 2001;183:6207–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvis S, Munder A, Ball G et al. Caenorhabditis elegans semi-automated liquid screen reveals a specialized role for the chemotaxis gene cheB2 in Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence. PLoS Pathog 2009;5:e1000540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellatly SL, Needham B, Madera L et al. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa PhoP-PhoQ two-component regulatory system is induced upon interaction with epithelial cells and controls cytotoxicity and inflammation. Infect Immun 2012;80:3122–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraud C, Bernard CS, Calderon V et al. The PprA–PprB two-component system activates CupE, the first non-archetypal Pseudomonas aeruginosa chaperone–usher pathway system assembling fimbriae. Environ Microbiol 2011;13:666–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooderham WJ, Gellatly SL, Sanschagrin F et al. The sensor kinase PhoQ mediates virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 2009;155:699–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooderham WJ, Hancock REW. Regulation of virulence and antibiotic resistance by two-component regulatory systems inPseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2009;33:279–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman AL, Kulasekara B, Rietsch A et al. A signaling network reciprocally regulates genes associated with acute infection and chronic persistence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Dev Cell 2004;7:745–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman AL, Merighi M, Hyodo M et al. Direct interaction between sensor kinase proteins mediates acute and chronic disease phenotypes in a bacterial pathogen. Gene Dev 2009;23: 249–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guragain M, King MM, Williamson KS et al. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 two-component regulator CarSR regulates calcium homeostasis and calcium-induced virulence factor production through its regulatory targets CarO and CarP. J Bacteriol 2016;198:951–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutu AD, Sgambati N, Strasbourger P et al. Polymyxin resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa phoQ mutants is dependent on additional two-component regulatory systems. Antimicrob Agents Ch 2013;57:2204–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guvener ZT, Harwood CS. Subcellular location characteristics of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa GGDEF protein, WspR, indicate that it produces cyclic-di-GMP in response to growth on surfaces. Mol Microbiol 2007;66:1459–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha D-G, O’Toole GA. c-di-GMP and its effects on biofilm formation and dispersion: a Pseudomonas aeruginosa review. Microbiol Spectr 2015;3:MB-0003-2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn HP. The type-4 pilus is the major virulence-associated adhesin of Pseudomonas aeruginosa – a review. Gene 1997;192:99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan M-E-T, van der Lelie D, Springael D et al. Identification of a gene cluster, czr, involved in cadmium and zinc resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene 1999;238:417–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay ID, Remminghorst U, Rehm BHA. MucR, a novel membrane-associated regulator of alginate biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl Environ Microb 2009;75:1110–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He K, Bauer CE. Chemosensory signaling systems that control bacterial survival. Trends Microbiol 2014;22:389–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeb S, Blumer C, Haas D. Regulatory RNA as mediator in GacA/RsmA-dependent global control of exoproduct formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0. J Bacteriol 2002;184:1046–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heurlier K, Williams F, Heeb S et al. Positive control of swarming, rhamnolipid synthesis, and lipase production by the posttranscriptional RsmA/RsmZ system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J Bacteriol 2004;186:2936–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman JW, Harwood CS. Identification of FleQ from Pseudomonas aeruginosa as a c-di-GMP-responsive transcription factor. Mol Microbiol 2008;69:376–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman JW, Tifrea DF, Harwood CS. A chemosensory system that regulates biofilm formation through modulation of cyclic diguanylate levels. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102:14422–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs M, Collie ESR, Free PD et al. PilS and PilR, a two-component transcriptional regulatory system controlling expression of type 4 fimbriae in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 1993;7:669–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu JL, Chen HC, Peng HL et al. Characterization of the histidine-containing phosphotransfer protein B-mediated multistep phosphorelay system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J Biol Chem 2008;283:9933–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, Whitchurch CB, Mattick JS. FimX, a multidomain protein connecting environmental signals to twitching motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 2003;185:7068–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huangyutitham V, Güvener ZT, Harwood CS. Subcellular clustering of the phosphorylated WspR response regulator protein stimulates its diguanylate cyclase activity. mBio 2013;4:e00242–00213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley BP, Goodman AL, Mumy KL et al. The two-component sensor response regulator RoxS/RoxR plays a role in Pseudomonas aeruginosa interactions with airway epithelial cells. Microb Infect 2010;12:190–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inclan YF, Persat A, Greninger A et al. A scaffold protein connects type IV pili with the Chp chemosensory system to mediate activation of virulence signaling in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 2016;101:590–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intile PJ, Diaz MR, Urbanowski ML et al. The AlgZR two-component system recalibrates the RsmAYZ posttranscriptional regulatory system to inhibit expression of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III secretion system. J Bacteriol 2014;196:357–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimoto KS, Lory S. Identification of pilR, which encodes a transcriptional activator of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa pilin gene. J Bacteriol 1992;174:3514–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain R, Behrens A-J, Kaever V et al. Type IV pilus assembly in Pseudomonas aeruginosa over a broad range of cyclic di-GMP concentrations. J Bacteriol 2012;194:4285–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansari VH, Potharla VY, Riddell GT et al. Twitching motility and cAMP levels: signal transduction through a single methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2016;363, doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnw119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jean-Pierre F, Tremblay J, Deziel E. Broth versus surface-grown cells: differential regulation of RsmY/Z small RNAs in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by the Gac/HptB system. Front Microbiol 2017;7:2168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeukens J, Boyle B, Kukavica-Ibrulj I et al. Comparative genomics of isolates of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa epidemic Strain associated with chronic lung infections of cystic fibrosis patients. PLoS One 2014;9:e87611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jochumsen N, Marvig RL, Damkiær S et al. The evolution of antimicrobial peptide resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is shaped by strong epistatic interactions. Nat Commun 2016;7:13002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanack KJ, Runyen-Janecky LJ, Ferrell EP et al. Characterization of DNA-binding specificity and analysis of binding sites of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa global regulator, Vfr, a homologue of the Escherichia coli cAMP receptor protein. Microbiology 2006;152:3485–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazmierczak BI, Lebron MB, Murray TS. Analysis of FimX, a phosphodiesterase that governs twitching motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 2006;60:1026–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns DB, Robinson J, Shimkets LJ. Pseudomonas aeruginosa exhibits directed twitching motility up phosphatidylethanolamine gradients. J Bacteriol 2001;183:763–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilmury SLN, Burrows LL. Type IV pilins regulate their own expression via direct intramembrane interactions with the sensor kinase PilS. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2016;113:6017–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong W, Chen L, Zhao J et al. Hybrid sensor kinase PA1611 in Pseudomonas aeruginosa regulates transitions between acute and chronic infection through direct interaction with RetS. Mol Microbiol 2013;88:784–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong W, Zhao J, Kang H et al. ChIP-seq reveals the global regulator AlgR mediating cyclic di-GMP synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nucleic Acids Res 2015;43:8268–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korgaonkar A, Trivedi U, Rumbaugh KP et al. Community surveillance enhances Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence during polymicrobial infection. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2013;110:1059–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreamer NN, Costa F, Newman DK. The ferrous iron-responsive BqsRS two-component system activates genes that promote cationic stress tolerance. mBio 2015;6:e02549–02514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchma SL, Connolly JP, O’Toole GA. A three-component regulatory system regulates biofilm maturation and type III secretion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 2005;187:1441–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchma SL, Ballok AE, Merritt JH et al. Cyclic-di-GMP-mediated repression of swarming motility by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: the pilY1 gene and its impact on surface-associated behaviors. J Bacteriol 2010;192:2950–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulasakara H, Lee V, Brencic A et al. Analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa diguanylate cyclases and phosphodiesterases reveals a role for bis-(3'-5')-cyclic-GMP in virulence. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103:2839–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulasekara HD, Ventre I, Kulasekara BR et al. A novel two-component system controls the expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa fimbrial cup genes. Mol Microbiol 2005;55:368–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski MA, Kazmierczak BI. Mutational analysis of RetS, an unusual sensor kinase-response regulator hybrid required for Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence. Infect Immun 2006;74:4462–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski MA, Osborn E, Kazmierczak BI. A novel sensor kinase–response regulator hybrid regulates type III secretion and is required for virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 2004;54:1090–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau CH-F, Fraud S, Jones M et al. Mutational activation of the AmgRS two-component system in aminoglycoside-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Ch 2013;57:2243–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau CH-F, Krahn T, Gilmour C et al. AmgRS-mediated envelope stress-inducible expression of the mexXY multidrug efflux operon of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. MicrobiologyOpen 2015;4:121–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laub MT, Goulian M. Specificity in two-component signal transduction pathways. Annu Rev Genet 2007;41:121–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J-Y, Ko KS. Mutations and expression of PmrAB and PhoPQ related with colistin resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates. Diagn Micr Infec Dis 2014;78:271–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leech AJ, Mattick JS. Effect of site-specific mutations in different phosphotransfer domains of the chemosensory protein ChpA on Pseudomonas aeruginosa motility. J Bacteriol 2006;188:8479–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]