Abstract

Importance

Largest analysis to date of tinnitus epidemiology in the American adult population

Objectives

To quantify the epidemiology and impact of tinnitus and to analyze its management in the United States relative to the 2014 American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation (AAO-HNSF) clinical practice guideline on tinnitus.

Design

Cross sectional analysis of a nationally representative health survey.

Methods

The 2007 National Health Interview Survey (raw N=75,764) was analyzed, identifying adults reporting tinnitus in the preceding 12 months.

Main Outcomes

In addition to quantifying duration, regularity, and severity of the tinnitus, specific data regarding noise exposure and tinnitus management during health care visits for tinnitus were analyzed.

Results

Among 222.1±3.4 million American adults, 21.4±3.4 million (9.6±0.3%) experienced tinnitus in the past 12 months. Among tinnitus sufferers, 27.0% had symptoms greater than 15 years; 36.0% had near constant symptoms. Higher rates of tinnitus were reported in those with consistent work (OR 3.3; CI: 2.9-3.7) and recreational time (OR 2.6; CI: 2.3-2.9) loud noise exposure. Years of work-related noise exposure correlated with increasing prevalence of tinnitus r=0.130 (95% CI, 0.103 to 0.157). 7.2% reported their tinnitus as a “big” or “very big” problem versus 41.6% reporting it as a “small” problem. Only 49.4% had discussed their tinnitus with a physician, where medications were the most frequently discussed recommendation (45.5%). Other interventions, such as hearing aids (9.2%), masking devices (4.9%), and cognitive-behavioral therapy (0.2%) were less frequently discussed.

Conclusions and Relevance

The contemporary national prevalence of tinnitus is approximately one in 10 adults. Durations of occupational and leisure time noise exposures correlated with rates of tinnitus and are likely targetable risk factors. Management options suggested by recently published guidelines were quite infrequently followed.

Introduction

Tinnitus is a symptom characterized by the perception of sound in the absence of an external stimulus.1 If persistent and either intolerable or sufficiently bothersome, it can cause functional impairment in thought processing, emotions, hearing, sleep, and concentration,1 all of which can substantially and negatively impact quality of life.2 It is a common problem for millions of people, as epidemiologic studies have reported its prevalence to be between 8 to 25.3% of the population of the United States.3–7 Similarly, population based studies conducted in other nations have found a similar prevalence of tinnitus, ranging from 4.6% to 30%.8–12

Given its high prevalence and impact on quality of life, the American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery Foundation (AAO-HNSF) recently published its first-ever, multi-disciplinary, evidence-based clinical practice guidelines to provide clinicians a framework for managing patients with tinnitus.13 In addition to outlining a suggested workup for persistent tinnitus, the authors also provided recommendations for and against various treatment options, including education and counseling, sound and cognitive behavioral therapy, medications, dietary supplementation, and acupuncture, among others.

To achieve targeted improvement in tinnitus management relative to the AAO-HNSF guidelines, data from the 2007 Integrated Health Interview Series (IHIS) was analyzed. IHIS is a project funded by the National Institutes of Health to supplement the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), a household-based, personal interview survey, administered by the United States Census Bureau and Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) since 1957. It serves as the largest source of health information of the U.S. civilian population. The information is collected from trained interviewers via a personal household interview. The sample is chosen at random, and starting in 2006, the minority population was oversampled in order to allow for more precise estimation of the socioeconomically mixed population of the U.S.

Uniquely in 2007, the IHIS survey asked respondents numerous questions about tinnitus symptoms, including inquiries about treatment strategies offered by their health care provider. Accordingly, these data represent the national trends in the management of tinnitus prior to the formulation of the recent guidelines referenced above. They may serve as a benchmark for the state of tinnitus counseling and treatment during this time and, by comparing and contrasting the survey results with the AAO-HNSF guidelines, we can identify and address deficiencies and areas for improvement. Thus, in the current study, we extracted data from this survey to (1) determine the prevalence, duration, frequency, severity of and common risk factors for tinnitus symptoms, and (2) report common interventions for tinnitus discussed by physicians to symptomatic patients. These survey results were then compared to AAO-HNSF recommendations to identify areas of potential improvement in the management of tinnitus, and to guide future studies in the management of tinnitus after the implementations of the above guidelines.

Materials and Methods

Adult responses in the household-based 2007 National Health Interview Series were analyzed as aggregated in the Integrated Health Interview Series.14 The study protocol was reviewed and deemed exempt from review by Partners Committee on Clinical Investigations as it analyzes publicly available, de-identified data. We have previously used the NHIS to describe the epidemiology of various otologic conditions in the United States.15,16 However, in 2007, the NHIS contained a specific module that assessed multiple tinnitus-related variables, including: presence or absence of tinnitus, duration, frequency, perceived severity of the problem, as well as healthcare seeking behaviors with respect to the tinnitus and treatments offered.

“The responses were obtained by trained interviewers via household surveys. Questions asked were typically simple; for example: “IN THE PAST 12 MONTHS, have you been bothered by ringing, roaring, or buzzing in your ears or head that lasts for 5 minutes or more?” The answer choices included options ranging from “not a problem” to small/moderate/big/very big problem, as well as declining to answer. Since these responses were collected through a rigorous, interview-based process, we can presume that the questions were understood, unbiased and appropriately guided by the interviewers. In addition to tinnitus variables, respondents were queried on noise exposure at work and during recreational time. When surveying work noise exposure, interviewers defined loud environments as those in which one must speak in a raised voice to be heard. In an effort to maintain uniformity, several particular recreational time activities such as use of gardening and workshop tools, machinery, motorcycles and other motor engines, loud household appliances, MP3 players, and concert attendance, among others, were queried.

Corresponding responses were extracted for adult patients (age≥18.0 years). Data were imported into SPSS (version 22.0) for analysis. The prevalence of self-reported tinnitus was determined along with various factors that further characterized the tinnitus symptom, including duration of the tinnitus, frequency and severity. This data was used to determine the associations between the prevalence of tinnitus and noise exposures. Thereafter, the proportion of respondents who discussed their tinnitus with their doctor and the proportions that subscribed to various remedies for their tinnitus were also calculated. Sample design weights were applied to the raw sample size to obtain representative statistics for the national population in the United States. Overall data are reported as the mean and its associated standard error of the weighted national sample. Statistical comparisons were conducted with chi-square, with significance set at p=0.05. Pearson’s correlation test was used to measure correlation between two variables, when reported.

Results

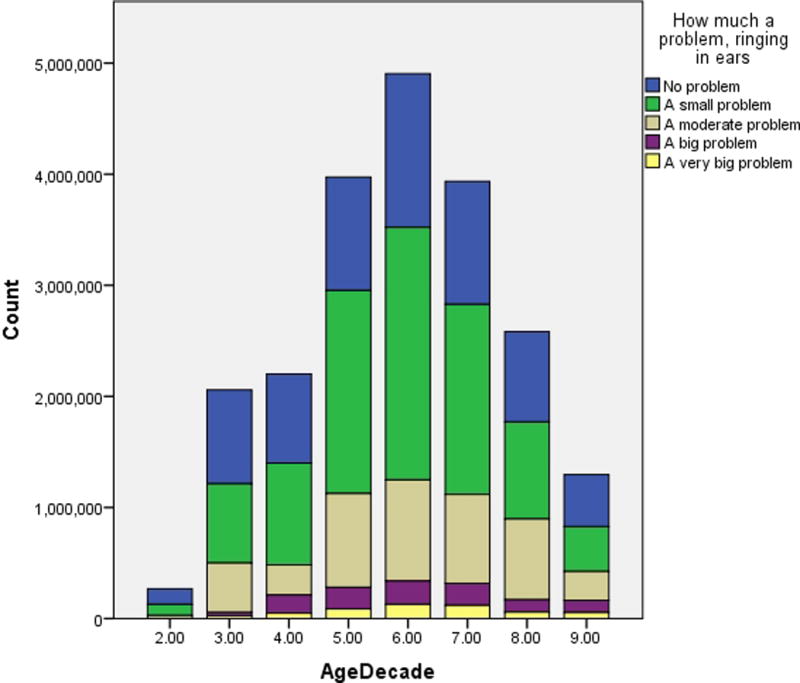

Among an estimated 222.1± 3.4 million adult individuals (raw N=75,764), 9.6±0.3% (21.4±3.4 million Americans) had experienced tinnitus in the past 12 months. When asked about the duration of symptoms, 56.1% of respondents with tinnitus experienced the problem for over 5 years, and 27.0% had symptoms for greater than 15 years. Mean age of those who had experienced tinnitus in the prior 12 months was significantly greater than those who did not have tinnitus (53.1 versus 45.0 years; Mean difference, 8.1 years; [95% confidence interval, 7.2–9.0 years]). We also note that those with more severe symptoms tended to be older, with a direct correlation seen between increased tinnitus severity and increased age (r=0.083; 95% CI, 0.042–0.125; Figure 1). Furthermore, tinnitus tended to be more prevalent in males (10.5%) than females (8.8%; mean difference, 1.8% [95% confidence interval 0.9–2.7%]), with no significant differences in severity between the two groups. Men were more likely than women to discuss tinnitus with their physician (52.8% versus 48.0%; Mean difference, 4.8% [95% confidence interval, 0.5–9.1%]; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Subjective severity of tinnitus symptoms, by age.

Table 1.

Gender Stratification of Tinnitus Symptoms

| Male | Female | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| N (millions) | Percent Within Sex (%) | N (millions) | Percent Within Sex (%) | ||

| Tinnitus in Last Year | 11.3 | 10.5 | 10.1 | 8.8 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Extent of Problem | |||||

| Not a Problem | 3.6 | 31.7 | 3.02 | 30.2 | |

| Small or Moderate Problem | 6.9 | 61.1 | 6.26 | 62.5 | |

| Big or Very Big Problem | 0.81 | 7.2 | 0.73 | 7.2 | |

|

| |||||

| Discussed with Doctor | 5.96 | 52.8 | 4.8 | 48 | 0.04 |

Out of those suffering from tinnitus, 36.0% reported having symptoms nearly constantly, 15.0% had noticeable symptoms at least once a day, 14.6% at least once a week, and the reminder had symptoms less than weekly. Regarding subjective severity, 7.2% believed it to be a big or a very big problem, 20.2% thought it was a moderate problem, 41.6% noted it to be a small problem, with the remainder not bothered by it at all. When asked about when they noticed the symptoms, over a third (38.4 %) noted their tinnitus at bedtime.

Among all respondents, 25.0% of adults reported a history of regular loud noise exposure at work, with duration of such exposure reported as 0 to 2 years (27.7%), 3–14 years (38.0%) and 15 or more years (34.3%). Those with a history of regular noise exposure at work had a 19.2% prevalence of tinnitus, versus 6.8% for those without (OR 3.3; CI: 2.9–3.7). Furthermore, there was an associated increase in the prevalence of tinnitus based on number of years exposed to work noise: 0-2 years with tinnitus prevalence of 12.9%, 3–14 years with 18.0%, and 15 or more years, 25.7% (r=0.130; 95% CI, 0.103 to 0.157; Table 2). A significant number of adults also reported exposure to loud recreational time noise at least once a month (22.7%). The prevalence of tinnitus for those with monthly leisure time loud noise exposure was 17.1%, versus 7.4% for those without such exposure (OR 2.6; CI: 2.3–2.9).

Table 2.

Rates of tinnitus among those reporting regular occupational loud noise exposure and in relation to reported duration of noise exposure.

| N (millions) |

% | Tinnitus Prevalence (%) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular Occupational Loud Noise Exposure, all respondents | ||||

|

| ||||

| No | 156.7 | 75.0 | 6.8 | |

|

| ||||

| Yes | 52.2 | 25.0 | 19.2 | < 0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Duration (years) | ||||

| 0-2 | 14.3 | 12.9 | ||

|

| ||||

| 3-14 | 19.7 | 18.0 | < 0.001 | |

|

| ||||

| >15 | 17.8 | 25.7 | ||

Out of those who experienced tinnitus, only about half had discussed their problem with a physician (50.6%). The various options discussed according to guidelines are outlined in Table 3 and alternative therapies discussed with patients but not included in the guidelines are described in Table 4. The responses indicated that a significant majority (84.8%) of patients had never tried any form of remedy. Compared to the recommendations elaborated by the AAO-HNSF tinnitus guideline, according to the current data, medical therapy was the most commonly discussed topic, while cognitive behavioral therapy was the least common.

Table 3.

Treatment options included in the AAO-HNSF guidelines discussed with physicians, among respondents reporting tinnitus.

| Types of Therapy Discussed | N (millions) | Percent of Patients (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Medications | 1.45 | 45.4 |

| Hearing Aids | 0.30 | 9.2 |

| Nutritional Supplementation | 0.25 | 7.8 |

| Stress Reduction Methods | 0.21 | 6.7 |

| Music Treatment | 0.13 | 4.0 |

| Tinnitus Retraining Therapy | 0.095 | 3.0 |

| Biofeedback Therapy | 0.089 | 2.8 |

| Wearable Masking Device | 0.082 | 2.6 |

| Non-Wearable Masking Device | 0.073 | 2.3 |

| Cognitive Behavioral Therapy | 0.0051 | 0.2 |

| Total | 2.68 | 83.8 |

Table 4.

Discussed management options not included in the AAO-HNSF guidelines, among respondents reporting tinnitus.

| Types of Therapy Discussed | N (millions) | Percent of Patients (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Psychiatric Therapy | 0.01 | 0.3 |

| Surgical Transection of Auditory Nerve | 0.04 | 1.2 |

| Alternative Medicine | 0.12 | 3.9 |

| “Other” Methods | 0.94 | 29.5 |

| Total | 1.11 | 34.9 |

Discussion

Tinnitus can be a severely debilitating problem, and numerous risk factors have been associated with the development of tinnitus. Those with a hearing impairment have a higher risk for tinnitus, and the associated increase in risk is dependent on the severity of hearing impairment.5,12,17,18 Furthermore, there is an elevated risk of tinnitus in people with a history of head injury, depressive symptoms, target shooting, arthritis, use of NSAID medications,5,19 hypertension, and smoking.7 In addition, individuals with intolerable tinnitus often suffer from higher rates of anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, and poor quality of life compared to those without tinnitus.12,20–23 Moreover, tinnitus is the most common service related disability among veterans, with over 1.1 million American veterans receiving disability payments for intolerable tinnitus in 2013.24

There are wide ranges of tinnitus prevalence reported from previous studies, possibly the result of variations in survey questioning and statistical methodologies. Most studies found that the prevalence of tinnitus in adults fell within the range of 8 to 30%.3–12,25 Although our reported prevalence among adults in the United States reporting tinnitus symptoms in the prior 12 months, is on the lower end of the range, it is noteworthy that the study reporting the highest prevalence of tinnitus (30%) limited their survey population to adults above the age of 55 years.12 This likely contributed to the relatively higher prevalence rate.

We also found that more males than females reported tinnitus, which is consistent with previously published findings.26,29 Additionally and similar to other large epidemiological studies in the United States, tinnitus severity directly correlated with age.4,7,29,31 However, we also see in this cohort that while the prevalence of tinnitus increased with age, it decreased in the older populations, beginning in the seventh decade, and this is represented in trends reported elsewhere (Figure 1).6,7

Loud noise exposure has been consistently linked to increased odds of hearing loss.1,5,7,26 In particular, occupational noise exposure risk has been associated with the development of tinnitus symptoms.10,25, 27–30 In contrast, the Beaver Dam Study6 failed to demonstrate an association between occupational noise exposure and the prevalence or incidence of tinnitus. In our sampled cohort, the majority of respondents denied regular loud noise exposure at work or during leisure hours, and did not experience even one episode of loud noise exposure at work in the prior 12 months. However, among the respondents with regular occupational noise exposure, the prevalence of tinnitus was higher than those without work noise exposure, and the rates of tinnitus increased with the reported duration of occupational noise exposure (Table 2). A similar relationship was seen among adults who reported exposure to monthly leisure time loud noise. Accordingly, the data suggests that while majority of respondents do not have regular work or leisure time loud noise exposure, when regularly exposed to environments with loud noise, tinnitus occurs at much higher rates, which are furthermore correlated to duration of noise exposure.

The AAO-HNSF guidelines are intended to address the management of the subset of tinnitus sufferers with symptom persistence for at least 6 months, which constitutes a large portion of our study cohort. The majority of respondents in our survey noted symptoms for over 12 months. However, independent of symptom duration, most of the respondents with tinnitus believed their symptoms to be “not a problem” or “only a small problem.” Similarly, 55.5% of respondents in the Blue Mountains Hearing Study reported their symptoms to be “mild.”31 Thus, it is evident that for many patients with chronic tinnitus, the severity of symptoms may actually be tolerable and do not require any intervention.

It has been noted that patients suffering from intolerable and bothersome tinnitus often experience sleep disturbance and poor quality of life, which can lead to mental distress, worsened anxiety and depression symptoms, and disability.7, 20–23 Despite this, we found that most had not discussed their problem with a physician, and many more had never tried any form of remedy. These figures are similar to those reported in the Blue Mountains Hearing Study, where only 37% sought help despite 50% of participants reporting a tinnitus problem for 6 years or more. Similar to our cohort, only 6% of patients reporting tinnitus in their study received a form of treatment.12

Of note and in the current study, less than one in four patients who discussed their tinnitus symptoms with their physician received management recommendations in concordance with the current AAO-HNSF guidelines. As seen in Table 3, the most commonly discussed intervention for tinnitus management was medical therapy. Although the treatment of comorbid mood disorders with psychoactive medications have been shown in some studies to reduce the severity of tinnitus,32,33 the AAO-HNSF recommends that clinicians should not use medical therapy, including antidepressant, anticonvulsant, and intratympanic medications, for routine management of tinnitus. Anxiolytics are also not recommended due to lack of consistent benefit, and potential adverse effects. The recommendation against medical therapy is primarily due to insufficient data from clinical trials and meta-analyses to reliably demonstrate a reduction in the perception of tinnitus.13

Although hearing aid evaluation for patients with hearing loss and tinnitus was a recommendation in the AAO-HNSF guidelines,13 we found that this topic was rarely discussed (Table 3). A hearing aid-like device can be used to also deliver sound therapy, which may provide respite from tinnitus. Although conclusive evidence behind the efficacy of sound therapy in the treatment of tinnitus is lacking,34 the AAO-HNSF guidelines encourage clinicians to regularly present it as an option for patients with persistent and bothersome tinnitus, given that there are no to minimal side effects or potential harm.13 Moreover, masking sound therapy can be delivered in the form of both wearable and non-wearable appliances and provide some benefit to tinnitus patients, but our results show that these therapeutic management strategies were infrequently discussed with our respondents seeking medical advice (Table 3).

Tinnitus symptoms can also lead to sleep, concentration, and emotional difficulties35, for which cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown to be beneficial.36,37 CBT aims to restructure distressful and dysfunction thoughts that lead to cognitive distortions into a more effective response to stressors. These techniques promote habituation and adaptive behaviors that may improve tinnitus tolerance, depression scores, and quality of life without directly impacting the severity or volume of tinnitus.37 However, the evidence supporting or refuting CBT’s effectiveness in improving tinnitus-specific quality of life is considered to be generally insufficient in some large reviews, mostly secondary to inconsistent study methodologies and lack of high powered studies.38 Regardless, even though CBT is a favored recommendation in the AAO-HNSF guidelines for the management of bothersome tinnitus and the good-practice guidelines of the Department of Health in the United Kingdom,38 CBT was rarely discussed with our cohort during physician-patient conversations regarding tinnitus (Table 3). CBT can furthermore be combined with education and counseling via informational brochures and self-help books, as well as stress management techniques, to provide effective management strategies for tinnitus. Unfortunately, as seen in Table 3, these adjunctive therapies were also seldom discussed with patients who presented to a physician with tinnitus symptoms.

The AAO-HNSF recommended against dietary supplementation, such as Ginkgo biloba, melatonin, and zinc, among others, given the preponderance of harm over clear benefit demonstrated in randomized clinical trials for any dietary supplementation.13 Nevertheless, nutritional supplementation was more often discussed than nearly every other recommended interventions listed in Table 3. Additionally, unconventional and unproven strategies, such as surgical transection of auditory nerve and alternative medicine were also discussed with patients (Table 4).

Tinnitus-related disability has been reported to be among the most common chronic conditions and in some populations even more prevalent than back and neck pain, knee problems, and diabetes mellitus.24 The negative impact on quality of life from chronic tinnitus is well-established, and like chronic daily headache39 and low back pain,40 has been reported to adversely affect all five measures of validated health-related quality of life surveys, including mobility, self-care, performance of usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression.41 Moreover, mood disorder comorbidity among tinnitus subjects has been reported to be as high as 60-80%42,43 and can lead to increases in measures of tinnitus annoyance.44 Similar findings are also seen in other common conditions, such chronic pain, where there the prevalence of major depressive disorder among chronic pain patients is over 50%,45 and low back pain, an ailment that is also associated with higher rates of depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders.46

There are several strengths and limitations to our study. The data is derived from a national database that represents a large and diverse sampling of the general citizen population. Additionally, each person is chosen in a way that they have a known non-zero probability of selection. Not only are all 50 states and the District of Columbia surveyed, additionally since 2006, the survey oversamples black, Hispanic, and Asian populations in order to more precisely estimate the health characteristics of the country’s minority population. Furthermore, this study is also the first to report the epidemiological data on the treatments for tinnitus discussed by physicians with their patients. However, the data analyzed here was extracted from the 2007 NHIS and may therefore not reflect the current tinnitus management practices of physicians nationally. Consequently, and with more recent public awareness and education about hearing loss and tinnitus, a higher percentage of tinnitus patients may be receiving management recommendations in line with the AAO-HNSF guidelines than reported here. Additionally, since 2007 was the first year tinnitus related information was available, future studies can be directed towards changes in tinnitus management patterns. Lastly, due to the retrospective nature of this study, there is potential for recall bias from the respondents, as they may have forgotten the details of, or failed to fully understand the tinnitus discussion topics and management recommendations from their healthcare providers.

Conclusion

The analysis of responses from 75,764 American adults, representing a sample of over 220 million people, confirms that tinnitus is prevalent in the general adult population. Reported rates of tinnitus are significantly higher in those with regular exposure to noisy environments at work and during leisure time. The recent guidelines published by the AAO-HNSF provide a logical framework for clinicians treating these patients, but the current results indicate that a vast majority of patients may not be offered management recommendations consistent with the suggested protocol. With the newly-published guidelines from the AAO-HNSF, otolaryngologists may play a greater role in addressing this issue, not only with managing their patients accordingly, but also in educating other physicians and healthcare providers. Future work can be directed to show changing patterns in tinnitus management before and after the implementation of these guidelines.

Acknowledgments

I, Jay Bhatt, had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Financial Support/Conflict of Interest: None

Neil Bhattacharyya, MD, is a consultant for IntersectENT, Inc. and Entellus, Inc.

Work Performed At: University of California, Irvine and Harvard Medical School

Contributor Information

Jay M. Bhatt, Department of Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery, Boston, MA

Harrison W. Lin, Department of Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery, Boston, MA

Neil Bhattacharyya, University of California, Irvine, and the Department of Otology & Laryngology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

References

- 1.Henry JA, Dennis KC, Schechter MA. General review of tinnitus: prevalence, mechanisms, effects, and management. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2005;48(5):1204–1235. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2005/084). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nondahl DM, Cruickshanks KJ, Dalton DS, et al. The impact of tinnitus on quality of life in older adults. J Am Acad Audiol. 2007;18:257–266. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.18.3.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams PF, Hendershot GE, Marano MA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Center for Health Statistics Current estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 1996. Vital Health Stat 10. 1999;(200):1–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kochkin S, Tyler R, Born J. The Prevalence of Tinnitus in the United States and the Self-Reported Efficacy of Various Treatments. Hearing Review. 2011;18(12):10–26. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nondahl DM, Cruickshanks KJ, Huang GH, et al. Tinnitus and its risk factors in the Beaver Dam offspring study. Int J Audiol. 2011;50(5):313–20. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2010.551220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nondahl DM, Cruickshanks KJ, Wiley TL, et al. Prevalence and 5-year Incidence of Tinnitus among Older Adults: The Epidemiology of Hearing Loss Study. J Am Acad Audiol. 2002;13:323–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shargorodsky J, Curhan GC, Farwell WR. Prevalence and characteristics of tinnitus among US adults. Am J Med. 2010;123(8):711–718. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jalessi M, Farhadi M, Asghari A, et al. Tinnitus: an epidemiologic study in Iranian population. Acta Med Iran. 2013;51(12):886–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quaranta A, Assennato G, Sallustio V. Epidemiology of hearing problems among adults in Italy. Scand Audiol Suppl. 1996;42:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park RJ, Moon JD. Prevalence and risk factors of tinnitus: the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2010–2011, a cross-sectional study. Clin Otolaryngol. 2014;39(2):89–94. doi: 10.1111/coa.12232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khedr EM, Ahmed MA, Shawky OA, et al. Epidemiological study of chronic tinnitus in Assiut, Egypt. Neuroepidemiology. 2010;35(1):45–52. doi: 10.1159/000306630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sindhusake D, Mitchell P, Newall P, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of tinnitus in older adults: The Blue Mountains Hearing Study. Int J Audiol. 2003b;2003;42:289–294. doi: 10.3109/14992020309078348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tunkel DE, Bauer CA, Sun GH, et al. Clinical practice guideline: tinnitus. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;151(2 Suppl):S1–S40. doi: 10.1177/0194599814545325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minnesota Population Center and State Health Access Data Assistance Center. Integrated Health Interview Series: Version 5.0. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin HW, Bhattacharyya N. Impact of dizziness and obesity on the prevalence of falls and fall-related injuries. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(12):2797–801. doi: 10.1002/lary.24806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roberts DS, Lin HW, Bhattacharyya N. Health care practice patterns for balance disorders in the elderly. Laryngoscope. 2013 Oct;123(10):2539–43. doi: 10.1002/lary.24087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sindhusake D, Golding M, Newall P, et al. Risk factors for tinnitus in a population of older adults: The Blue Mountains Hearing Study. Ear Hear. 2003;24:501–507. doi: 10.1097/01.AUD.0000100204.08771.3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Axelsson A, Ringdahl A. Tinnitus—a study of its prevalence and characteristics. Br J Audiol. 1989;23:53–62. doi: 10.3109/03005368909077819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nondahl DM, Cruickshanks KJ, Wiley TL, et al. The ten-year incidence of tinnitus among older adults. Int J Audiol. 2010;49(8):580–585. doi: 10.3109/14992021003753508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chandra RK, Epstein VA, Fishman AJ. Prevalence of depression and antidepressant use in an otolaryngology patient population. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141:136–138. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Folmer RL, Griest SE. Tinnitus and insomnia. Am J Otolaryngol. 2000;21:287–293. doi: 10.1053/ajot.2000.9871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crocetti A, Forti S, Ambrosetti U, Bo LD. Questionnaires to evaluate anxiety and depressive levels in tinnitus patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140:403–405. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krog NH, Engdahl B, Tambs K. The association between tinnitus and mental health in a general population sample: results from the HUNT Study. J Psychosom Res. 2010;69(3):289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Department of Veterans Affairs, editor. Annual Benefits Report: Fiscal Year 2013. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffman HJ, Reed GW. Epidemiology of tinnitus. In: Snow JB Jr, editor. Tinnitus: Theory and Management. Hamilton, Ontario: BC Decker Inc; 2004. pp. 16–41. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gopinath B, McMahon CM, Rochtchina E, Karpa MJ, Mitchell P. Incidence, persistence, and progression of tinnitus symptoms in older adults: the Blue Mountains Hearing Study. Ear Hear. 2010;31(3):407–412. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181cdb2a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rubak T, Kock S, Koefoed-Nielsen B, et al. The risk of tinnitus following occupational noise exposure in workers with hearing loss or normal hearing. Int J Audiol. 2008;47:109–114. doi: 10.1080/14992020701581430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palmer KT, Griffin MJ, Syddall HE, et al. Occupational exposure to noise and the attributable burden of hearing difficulties in Great Britain. Occup Environ Med. 2002;59:634–9. doi: 10.1136/oem.59.9.634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Engdahl B, Krog NH, Kvestad E, Hoffman HJ, Tambs K. Occupation and the risk of bothersome tinnitus: results from a prospective cohort study (HUNT) BMJ Open. 2012;21:2. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000512. 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Engdahl B, Tambs K. Occupation and the risk of hearing impairment–results from the Nord-Trøndelag study on hearing loss. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2010;36(3):250–257. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gopinath B, McMahon CM, Rochtchina E, Karpa MJ, Mitchell P. Risk factors and impacts of incident tinnitus in older adults. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20(2):129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Folmer RL, Griest SE, Meikle MB, Martin WH. Tinnitus severity, loudness, and depression. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;121:48–51. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(99)70123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Folmer RL, Shi YB. SSRI use by tinnitus patients: interactions between depression and tinnitus severity. Ear Nose Throat J. 2004;83:107–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hobson J, Chisholm E, El Refaie A. Sound therapy (masking) in the management of tinnitus in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD006371. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006371.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Erlandsson SI. Psychological profiles of tinnitus patients. In: Tyler RS, editor. Tinnitus Handbook. San Diego, CA: Thomson Learning; 2000. pp. 25–57. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hesser H, Weise C, Westin VZ, Andersson G. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive-behavioral therapy for tinnitus distress. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:545–553. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinez-Devesa P, Perera R, Theodoulou M, Waddell A. Cognitive behavioural therapy for tinnitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;9:CD005233. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005233.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ear, Nose, Throat and Oral Conditions: Evidence-Based Reports. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: May, 2015. Evaluation and Treatment of Tinnitus: Comparative Effectiveness. http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/evidence-based-reports/clinical/ent/index.html. Accessed Aug 21 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cho SJ, Song TJ, Chu MK. Outcome of Chronic Daily Headache or Chronic Migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2016 Jan;20(1):2. doi: 10.1007/s11916-015-0534-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cedraschi C, Luthy C, Allaz AF, Herrmann FR, Ludwig C. Low back pain and health-related quality of life in community-dwelling older adults. Eur Spine J. 2016 Mar 7; doi: 10.1007/s00586-016-4483-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joo YH, Han KD, Park KH. Association of Hearing Loss and Tinnitus with Health-Related Quality of Life: The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. PLoS One. 2015 Jun 29;10(6):e0131247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sullivan MD, Katon W, Dobie R, Sakai C, Russo J, Harrop-Griffiths J. Disabling tinnitus. Association with affective disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1988;10(4):285–91. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(88)90037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zoger S, Svedlund J, Holgers KM. The effects of sertraline on severe tinnitus suffering — a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006 Feb;26:32–9. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000195111.86650.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kehrle HM, Sampaio AL, Granjeiro RC, de Oliveira TS, Oliveira CA. Tinnitus Annoyance in Normal-Hearing Individuals: Correlation With Depression and Anxiety. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2016 Mar;125(3):185–94. doi: 10.1177/0003489415606445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elliott TE, Renier CM, Palcher JA. Chronic pain, depression, and quality of life: correlations and predictive value of the SF-36. Pain Med. 2003 Dec;4(4):331–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2003.03040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gore M, Sadosky A, Stacey BR, Tai KS, Leslie D. The burden of chronic low back pain: clinical comorbidities, treatment patterns, and health care costs in usual care settings. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012 May 15;37(11):E668–77. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318241e5de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]