Abstract

Aim

To investigate the effect of push-up training with a similar load of to 40% of 1- repetition maximumal (1RM) bench press on muscle hypertrophy and strength gain in men.

Methods

Eighteen male participants (age, 20.2 ± 0.73 years, range: 19−22 years, height: 169.8 ± 4.4 cm, weight: 64.5 ± 4.7 kg) were randomly assigned to one of two experimental groups: bench press at 40%1RM (bench-press group, n = 9) or push-ups with position adjusted (e.g. kneeling) to the same load of bench-press 40%1RM (push-up group, n = 9), performed twice per week for 8 weeks. Muscle thickness at three sites (biceps, triceps, and pectoralis major), bench-press 1RM, maximum repetition at 40%1RM, and power output (medicine ball throw) were measured before and after the training period.

Results

Significant increases in 1RM and muscle thickness (triceps and pectoralis major) were observed in bench-press group (1RM, from 60.0 ± 12.1 kg to 65.0 ± 12.1 kg, p < 0.01; triceps, from 26.3 ± 3.7 mm to 27.8 ± 3.8 mm, p < 0.01; pectoralis major, from 17.0 ± 2.8 mm to 20.8 ± 4.8 mm, p < 0.01) and in the push-up group (1RM, from 61.1 ± 12.2 kg to 64.2 ± 12.5 kg, p < 0.01; triceps, 27.7 ± 5.7 mm to 30.4 ± 6.6 mm, p < 0.01; pectoralis major, from 17.0 ± 2.8 mm to 20.8 ± 4.8 mm, p < 0.01). Biceps thickness significantly increased only in the bench-press group (28.4 ± 3.3 mm to 31.5 ± 3.7 mm, p < 0.01). Neither power output performance nor muscle endurance capacity changed in either group.

Conclusions

Push-up exercise with similar load to 40%1RM bench press is comparably effective for muscle hypertrophy and strength gain over an 8-week training period.

Keywords: 1 repetition maximal, Bodyweight training, Exercise load, Muscle thickness

1. Introduction

The push-up is a very popular bodyweight-based strength training exercise for fitness in athletes and general populations.1, 2, 3, 4 The push-up can be performed without any additional tools, and its intensity can be altered with several variations, making it suitable for almost every level of fitness.5, 6 In addition, “bodyweight training” was selected the top 3 fitness trend in the past consecutive 3 years of the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) trend words in 2015 to 2017.7 Although the push-up exercise is undoubtedly useful and important, chronic adaptations to push-ups, particularly muscle hypertrophy, remain unclear.

Strength training load is usually determined relative to one repetition maximum (1RM), and the training load for muscle hypertrophy is typically set to more than 70%1RM.8 A recent study suggested that low-intensity strength training such as 30% 1RM induced muscle gain, if it was performed to failure.9 A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies to compare the effects of low-load versus high-load training for improving muscle strength and muscle development suggested that low-load resistance training led to similar muscle gain compared with high-load resistance training, but a lower tendency for strength gain was observed with low-load training.10

Bench press and push-up have been shown to elicit similar muscle activation patterns on electromyography.1, 11 Calatayud et al. reported that the elastic-resistance push-up exercise and bench press induced similar EMG values, as well as similar strength gains when both exercises were performed at the same intensity and speed of movement over 6 weeks, thus demonstrating a relationship between similar acute muscle activations and changes in muscle strength.12 However, to our knowledge, no studies have investigated whether push-up training induces muscle gain similar to that of bench-press training.

Ebben et al.5 investigated push-up variations including different levels of foot and hand elevation and bent-knee and normal position and observed ground reaction forces of approximately 64% and 49% of body weight in the regular and bent-knee push-up conditions, respectively. Other studies reported similar results.13 These findings indicated that the intensity of push-up exercise can be adjusted to a suitable intensity for low-load training.

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether low-load bench-press and push-up exercise at similar intensity (40%1RM) performed to failure induced comparable muscle hypertrophy and strength gain in untrained men. We hypothesized that these exercises would lead to similar muscle hypertrophy and strength gain after an 8-week training program.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

Subjects were randomly assigned to an experimental group: bench press and sprint push-up group. A supervised progressive RT program designed to induce muscular hypertrophy (40%1RM of bench press) was performed in 8-week with training carried out 2 times per week on nonconsecutive days. Muscle thickness at three sites (biceps brachii, triceps brachii, and pectoralis major), bench press 1RM, ball throwing, and maximum repetition were measured at 3 time points (two baseline tests and once after 8 weeks of training). Post measurements were performed at intervals of 48 hours from final training session. Test-retest reliability analyses revealed intra-class correlation coefficients of 0.703−0.986. Two-way ANOVA with repeated measures and Bonferroni post hoc tests were conducted to assess the effects. All testing and training were supervised by a National Strength and Conditioning Association, Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist (NSCA–CSCS) and supervisors were blinded about the purpose of the study.

2.2. Subjects

Eighteen collegiate male students majoring physical education (age: 20.2 ± 0.7 years, age range: 19−22 years, height: 169.8 ± 4.4 cm, weight: 63.2 ± 6.3 kg) volunteered to participate in this study. The subjects were recreational noncompetitive exercisers with minimum resistance training experience of 1 year and were randomly assigned to bench-press group (n = 9 age: 20.1 ± 0.6 years, height: 171.4 ± 3.8 cm, weight: 63.3 ± 5.8 kg), push-up group (n = 9 age: 20.3 ± 0.8 years, height: 168.1 ± 4.5 cm, weight: 63.1 ± 7.2 kg). All participants were informed about the potential risks of the experiment and gave their written consent to participate. The study was approved by the ethics committee of our institution and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki for Human Research.

2.3. Training protocols

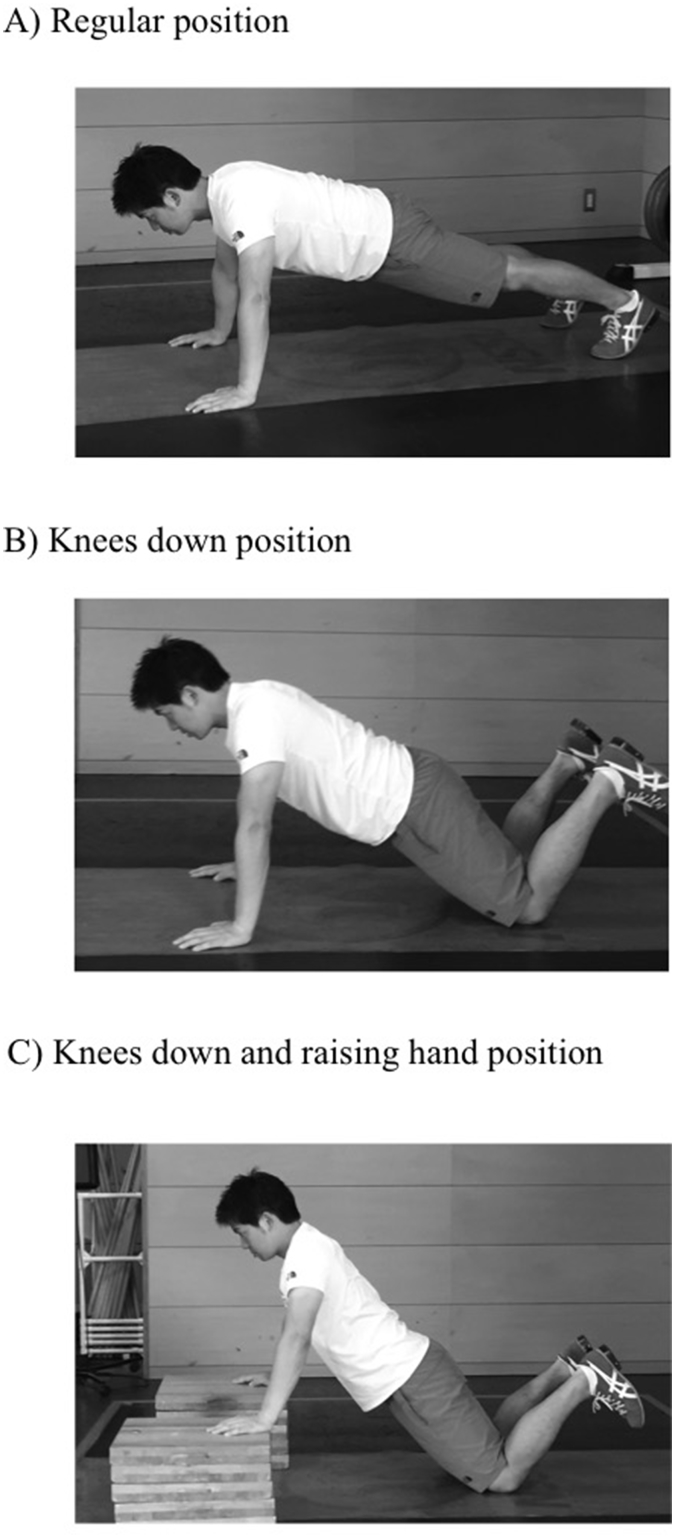

All training session was performed at training center in Nippon Sport Science University, Tokyo, Japan at noon (P.M. 0:00-1:00). Subjects were randomly assigned to the two experimental groups. One group performed 3 sets of bench press exercise at 40% 1RM (bench-press group, n = 9), and the other performed 3 sets of push-ups with their position adjusted to the same load, 40% 1RM, as the bench press (push-up group, n = 9) (Fig. 1). The intensity of push up group was fixed according to previous studies5, 6 and repetitions of each session. Both training groups performed the exercises to failure with 2-min rest intervals, twice per week for 8 weeks. Immediately after each training session, subjects consumed a source of high-quality protein (DNS Protein, 132 kcal, 24.4 g protein, 3.6 g carbohydrate, 2.3 g fat; DNS, Tokyo, Japan) in conjunction with 300 ml of water to standardize the post-exercise meal.

Fig. 1.

Push-up exercise variations: regular position (A), knees bent position (B), and knees bent and hands elevated position (C). A previous study suggested that regular position and knees bent position represented 64% and 49% of body weight5, 6 (17).

One-repetition maximum test and maximum repetition test

All subjects performed the 1RM test using free-weight bench press using methods previously described by Hoffman.14 Before the test, subjects were given instructions on proper techniques and test procedures. After a warm-up consisting of several sets of 6 to 10 repetitions using a light load, each participant attempted a single repetition with a load believed to be approximately 90% of his maximum. If the attempt was successful, weight was added, depending on the ease with which the single repetition was completed. If the attempt was not successful, weight was removed from the bar, and the exercise was repeated. Participants rested for a minimum of 3 minutes between maximal attempts. This procedure continued until the participant was unable to complete a single repetition through the full range of motion. Each participant's 1RM was defined as the heaviest load at which the exercise could be performed in proper form and was usually achieved in 3 to 5 attempts. Muscle endurance capacity was measured by maximal repetition test of bench press with 40% 1RM based on recent 1RM test. More than 24h after 1RM tests, subjects performed a warm-up consisting of several sets of 6 to 10 repetitions using a light load, and performed maximal effort repetition tests on the bench press to determine the repetitions and work volumes. Attempts of 1RM and maximal repetition test that did not meet the range of motion criterion for each exercise, as determined by the researcher, were discarded. The subjects were required to lower the bar to their chest before initiating concentric movement. Their grip widths were measured and recorded for later use. All testing was completed under the supervision of NSCA-CSCS.

2.4. Muscle thickness

Muscle thickness was measured using B-mode ultrasound system and software (Aloka SSD-3500, Tokyo, Japan) at three sites: the biceps and triceps brachii at 60% of the distance from the lateral epicondyle of the humerus to the acromial process of the scapula, and the pectoralis major at the site between third and fourth of ribs under the midpoint of the clavicle.15 Before testing, measurement points on the biceps, triceps, and pectoralis major were marked, and the same measurement points were used for each testing session. The measurements were carried out while the subjects stood with their elbows extended and relaxed. The subcutaneous adipose tissue-muscle interface and the muscle-bone interface were identified from the ultrasonographic image, and the distance between the two interfaces was defined as muscle thickness. Measurements were taken a week prior to the start of training, and 48-hour after the final training session.

2.5. Medicine ball throw test

The assessment of upper-body power output performance was conducted using the kneeling medicine ball throw test using 2kg and 4kg medicine ball. Subjects start in a kneeling position and the thighs should be parallel and the knees at the start line, then in one motion the ball is pushed forward and up. The knees are not to leave the ground during throw. Two attempts are performed with at least 45 seconds recovery between each throw, and the best recorded attempt was used as the representative value. All testing was completed under the supervision of NSCA-CSCS.

2.6. Statistical analysis

SPSS statistical software, version 22.0 for Macintosh, was used to perform all statistical evaluations. A two-way mixed ANOVA (groups × time) was performed to assess training-related differences in the bench-press and push-up groups for each dependent variable. In addition, Bonferroni's post-hoc test was performed to evaluate training-related changes within groups. Cohen's d effect sizes were estimated for all observations to compare the magnitude of training response, with ≤0.20 representing a small effect, 0.50 representing a medium effect, and ≥0.80 representing a large effect.16 The threshold for significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Muscle hypertrophy

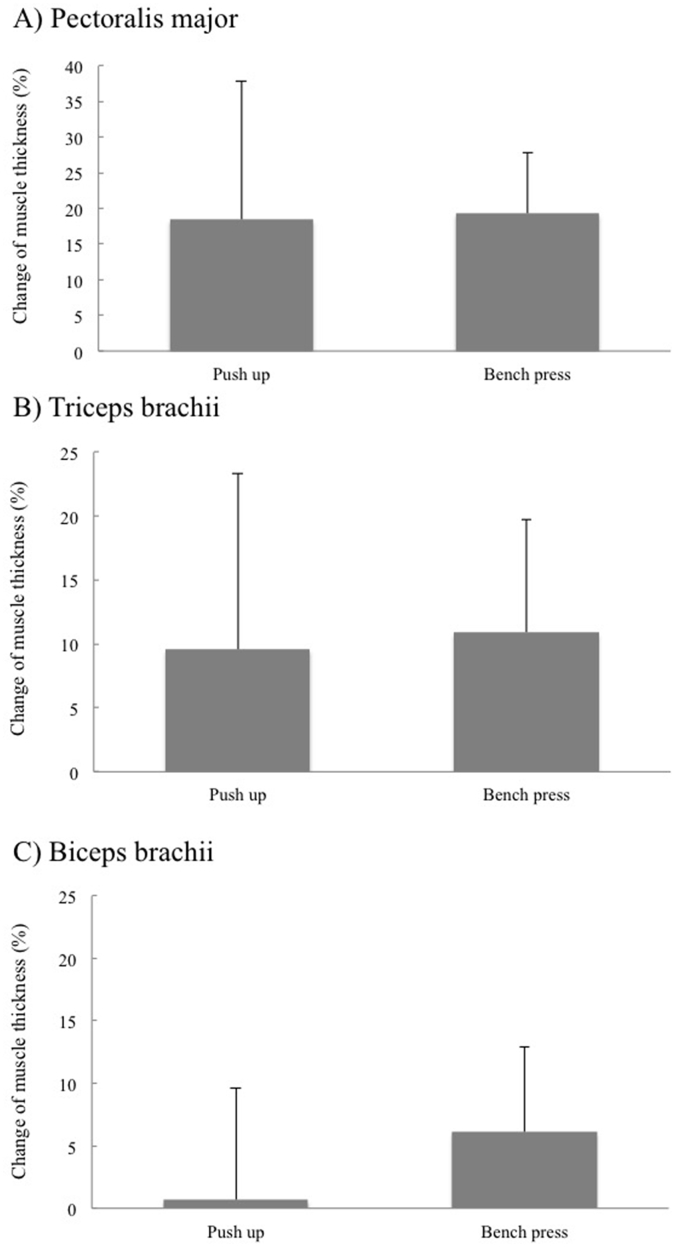

Significant increases in muscle thickness (triceps and pectoralis major) were observed in the bench-press group (triceps, from 26.3 ± 3.7 mm to 27.8 ± 3.8 mm, p < 0.01; PM, from 17.0 ± 2.8 mm to 20.8 ± 4.8 mm, p < 0.01) and in the push-up group (triceps, from 27.7 ± 5.7 mm to 30.4 ± 6.6 mm, p < 0.01; pectoralis major, from 17.0 ± 2.8 mm to 20.8 ± 4.8 mm, p < 0.01). Significant increase in biceps muscle thickness was observed only in the bench-press group (from 28.4 ± 3.3 mm to 31.5 ± 3.7 mm, p < 0.01), with no significant change in the push-up group (from 29.3 ± 5.0 mm to 30.3 ± 4.6, p = 0.315). The change in muscle thickness at the three sites is shown in Fig. 2. There was no significant difference between the groups.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of % changes in muscle thickness of the pectoralis major (A), triceps brachii (B), and biceps brachii (C) between the push-up and bench press groups after the 8-week training period. Values are mean ± S.D. There is no significant difference.

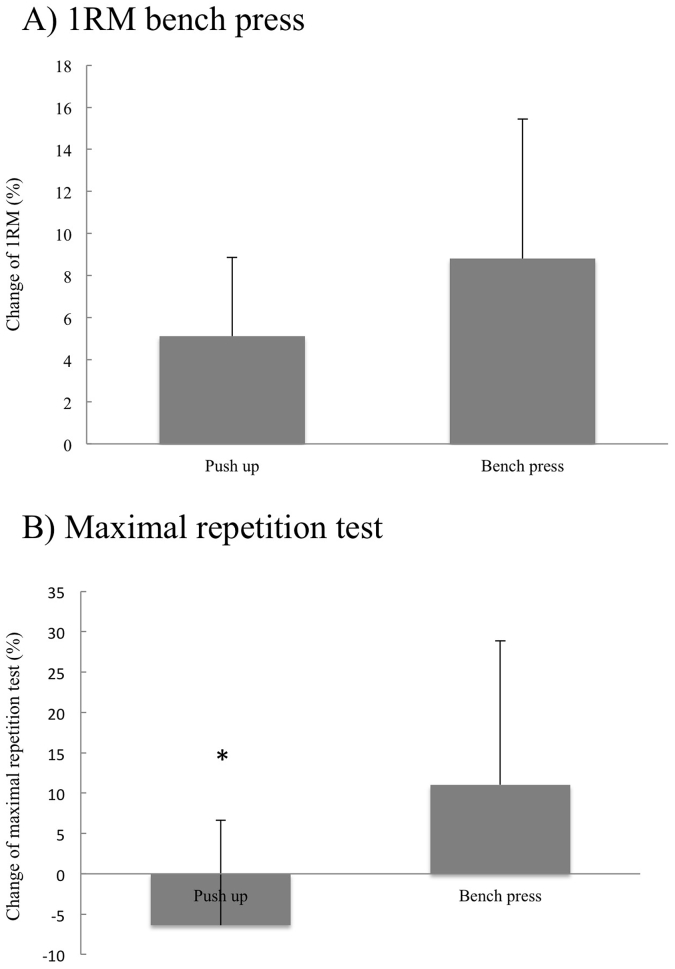

3.2. Muscle strength and performance

Significant increases in 1RM were observed in the bench-press group (from 60.0 ± 12.1 kg to 65.0 ± 12.1 kg, p < 0.01) and in the push-up group (from 61.1 ± 12.2 kg to 64.2 ± 12.5 kg, p < 0.01) (Table 1). No significant change was observed in medicine ball throwing or maximum repetition test. There was significant difference in % increase of muscle endurance capacity between groups (P < 0.01), but not in power output performance (Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Effect on parameters of 8 weeks of push-up training (n = 9) and bench-press training (n = 9).

| Parameter tested | Training condition | Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | P Value | ES (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (kg) | Push-up | 63.1 ± 7.2 | 63.7 ± 7.9 | 0.403 | 0.08 (−0.85–1.00) |

| Bench-press | 63.3 ± 5.8 | 64.1 ± 6.2 | 0.427 | 0.13 (−0.80–1.05) | |

| MT-BB (mm) | Push-up | 29.3 ± 5.0 | 30.3 ± 4.6 | 0.315 | 0.21 (−0.73–1.12) |

| Bench-press | 28.4 ± 3.3 | 31.5 ± 3.7 | 0.000∗∗ | 0.88 (−0.12–1.81) | |

| MT-TB (mm)† | Push-up | 27.5 ± 5.7 | 30.4 ± 6.6 | 0.007∗∗ | 0.47 (−0.49–1.38) |

| Bench-press | 26.3 ± 3.7 | 27.8 ± 3.8 | 0.005∗∗ | 0.40 (−0.24–1.94) | |

| MT-PM (mm)† | Push-up | 17.0 ± 2.8 | 20.8 ± 4.8 | 0.008∗∗ | 0.97 (−0.05–1.89) |

| Bench-press | 17.8 ± 3.3 | 22.5 ± 5.0 | 0.001∗∗ | 1.11 (0.07–2.04) | |

| 1RM (kg)† | Push-up | 61.1 ± 12.2 | 64.2 ± 12.5 | 0.002∗∗ | 0.25 (−0.69–1.17) |

| Bench-press | 60.0 ± 12.1 | 65.0 ± 12.1 | 0.003∗∗ | 0.41 (−0.54–1.33) | |

| 2 kg MB throw (cm) |

Push-up | 584.4 ± 63.3 | 593.3 ± 56.5 | 0.466 | 0.15 (−0.78–1.07) |

| Bench-press | 546.7 ± 63.4 | 560.0 ± 66.0 | 0.347 | 0.21 (−0.73–1.12) | |

| 4kg MB throw (cm) |

Push-up | 411.1 ± 41.7 | 420.0 ± 38.7 | 0.198 | 0.22 (−0.72–1.14) |

| Bench-press | 402.2 ± 40.2 | 415.0 ± 54.3 | 0.064 | 0.27 (−0.67–1.18) | |

| Maximal Rep (times) |

Push-up | 31.3 ± 5.2 | 29.6 ± 7.6 | 0.228 | −0.26 (−1.18–0.68) |

| Bench-press | 29.8 ± 2.8 | 32.8 ± 4.0 | 0.114 | 0.87 (−0.14–1.79) |

MT, muscle thickness; BB, biceps brachii; TB, triceps brachii; PM, pectoralis major; 1RM, 1 repetition maximum; MB, medicine ball; ES, Effect size; 95%CI; 95% confidence interval. Values are mean ± S.D.

†p < 0.05 significant main effect (time) by 2-way ANOVA.

∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 significant difference after training by Bonferroni post-hoc test.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of % changes in 1RM strength (A) and maximal repetition test (B) between push-up and bench press groups after the 8-week training period. Values are mean ± S.D. *p < 0.05 significant difference compared with bench press group.

4. Discussion

This investigation is the first to compare muscle hypertrophy between low-intensity bench-press and push-up training performed with similar intensity, rest interval, and speed of movement. We found that push-up training induced similar increases in muscle thickness of the triceps and pectoralis major to the 40% 1RM bench press. Similar strength gains were also observed in both groups. In present study, three site of ultrasonography measurement were performed as the indicator of muscle hypertrophy, however, muscle thickness is not a direct measurement for indicating muscle hypertrophy.15, 17

The relationship between low-intensity bodyweight training and muscle hypertrophy has not been previously reported. The main finding of the present study was that low-intensity bodyweight training induced muscle hypertrophy, with increased in muscle thickness of the pectoralis major (push-up: 18.3%, bench press: 19.4%) and triceps (push-up: 9.5%, bench press: 10.3%). These results are consistent with a previous study15 reporting that resistance training at 40%1RM resulted in a 24% increase in muscle thickness in untrained young men. In the present study, a 19.4% increase in muscle thickness of pectoralis major was observed in the bench-press group after an 8-week training session. The percent change of muscle thickness in the bench-press group was similar to that previously reported for 8-week training periods in untrained young men.15 A recent study suggested that low-load (30% 1RM) was as effective as high-load training (80% 1RM) for increasing muscle protein synthesis and signaling such as mTOR, p70S6K, and ERE1/2 in acute response of resistance exercise to volitional failure, and that 10-week leg extension resistance training protocols involving 3 sets of low-load (30% 1RM) or high-load (80% 1RM) intensity, but not 1 set of high-load intensity, induced muscle hypertrophy.9 The present study extends this observation by showing that low-load resistance training to failure involving either bench press or push-up is also effective for muscle hypertrophy.

Bench-press exercise is performed in a supine position on the bench. By contrast, the push-up is performed in a prone position and involves greater latissimus dorsi muscle activation.18 However, Calatayud et al.12 reported comparable levels of muscle activation during push-up and bench press and comparable muscle strength gains after 8 weeks of training with either exercise. Our results further suggest that push-up training induces similar muscle hypertrophy to bench-press training in the pectoralis major and triceps.

A previous study indicated that push-up training on a stable or unstable surface does not provide significant improvement in muscle strength or endurance in 8 weeks.2 Since each group performed three sets of 10 repetitions, the authors speculated that low training volume is a possible explanation for the lack of a statistically significant difference. On other hand, in the study by Calatayud et al.12 investigated push-up with elastic-band resistance to achieve the same muscle activation as 6RM bench press and found that 5 weeks of push-up exercise with similar EMG activity to bench press was effective for muscle strength gain (percent change of 1RM: 13%). In our study, push-ups and bench press performed at a similar intensity of 40%1RM induced comparable strength gain. Since subjects in our study performed exercises to failure, sufficient training volume was achieved. In our study, the percent changes of 1RM in push-up and bench press were 5% and 8%, respectively. Although the strength increase was lower than that reported by Calatayud et al.,12 push-up training without any resistive staffs is effective for strength gain.

Although we observed a significant 8% increase in biceps muscle thickness in the bench-press group, biceps muscle hypertrophy has not been previously reported in bench-press training.15 Since certified training experts supervised their training, they performed the bench press exercise with a standard technique. It is a very low possibility, but they might perform the bench press with a wide or narrow grip. It induced greater biceps muscle activation compared to the middle grip,19 which may have led to biceps hypertrophy, but not in push up group in our study.

We did not observe an improvement in performance parameters such as endurance and power output performance. In endurance performance, we measured maximal repetition test for bench press using relative intensity such as 40% 1RM based on recent 1RM test in present study. Nevertheless, 1RM strength following low intensity strength training increase in both groups and intensity was higher in post-test than pre-test. However, bench press group has higher % change in muscle endurance than push up group, because of specific adaptation to imposed demands. Improvement in power output parameters requires high intensity, high-velocity resistance training, and/or plyometric training.20, 21 By contrast, we investigated low-intensity exercise with controlled movement and speed. Several authors examining the activation patterns of active muscles during variants of the push-up have reported altered electromyography levels. In addition, it may be necessary to consider not only the load of the exercise but also movement speed, such as by using plyometric push-ups, for improvements in physical performance.

The following limitations may have effects on interpreting the results of the present study. First, we could not controlled dietary intakes and physical activity level in present study. Second, we could not measured latissimus dorsi thickness as well and might be there any differences here between groups. Third, the lack of an electromyography analysis and assessment of subjects of recreational noncompetitive exercisers prevent a comparison of our results with previous studies such as that of Calatayud et al.,12 who reported that in trained subjects, 6RM bench press and push-up comparable gains in muscle strength, but no difference in muscle function or performance between low-intensity and high-intensity resistance training. Future studies are necessary to ascertain the effects of push-up and bench press with similar intensity on muscle hypertrophy and strength gains in highly trained subjects.

In conclusion, push-up and bench-press exercise at 40%1RM over 8 weeks are similarly effective for increasing muscle thickness and strength gain. The intensity of push-up can be altered with the use of push-up variations, such as with knees bent or changing hand or foot elevation, the exercise can be performed at 40−75% of body weight,5, 6 and it can be performed at higher loads by using an elastic band or weight plate on the back.11 These data and our present results can be used to quantify the approximate load as a percentage of body mass for the purpose of quantifying load and volume in a resistance training program to enhance upper body fitness.

References

- 1.Calatayud J., Borreani S., Colado J.C. Muscle activity levels in upper-body push exercises with different loads and stability conditions. Phys Sportsmed. 2014;42:106–119. doi: 10.3810/psm.2014.11.2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chulvi-Medrano I., Martinez-Ballester E., Masia-Tortosa L. Comparison of the effects of an eight-week push-up program using stable versus unstable surfaces. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2012;7:586–594. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin R.C., Grier T., Canham-Chervak M. Validity of self-reported physical fitness and body mass index in a military population. J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30:26–32. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000001026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Speranza M.J., Gabbett T.J., Johnston R.D. Muscular strength and power correlates of tackling ability in semiprofessional rugby league players. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29:2071–2078. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ebben W.P., Wurm B., VanderZanden T.L. Kinetic analysis of several variations of push-ups. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25:2891–2894. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31820c8587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suprak D.N., Dawes J., Stephenson M.D. The effect of position on the percentage of body mass supported during traditional and modified push-up variants. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25:497–503. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181bde2cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson W.R. Worldwide survey of fitness trends for 2017. ACSMs Health Fit J. 2016;20:8–17. [Google Scholar]

- 8.American College of Sports M American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exer. 2009;41:687–708. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181915670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell C.J., Churchward-Venne T.A., West D.W. Resistance exercise load does not determine training-mediated hypertrophic gains in young men. J Appl Physiol. 2012;113:71–77. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00307.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schoenfeld B.J., Wilson J.M., Lowery R.P. Muscular adaptations in low- versus high-load resistance training: a meta-analysis. Eur J Sport Sci. 2016;16:1–10. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2014.989922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blackard D.O., Jensen R.L., Ebben W.P. Use of EMG analysis in challenging kinetic chain terminology. Med Sci Sports Exer. 1999;31:443–448. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199903000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calatayud J., Borreani S., Colado J.C. Bench press and push-up at comparable levels of muscle activity results in similar strength gains. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29:246–253. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gouvali M.K., Boudolos K. Dynamic and electromyographical analysis in variants of push-up exercise. J Strength Cond Res. 2005;19:146–151. doi: 10.1519/14733.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofman J.R. Human Kinetics; Champaugn: 2014. Physiological Aspects of Sport Training Abd Performance. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogasawara R., Thiebaud R.S., Loenneke J.P. Time course for arm and chest muscle thickness changes following bench press training. Interv Med Appl Sci. 2012;4:217–220. doi: 10.1556/IMAS.4.2012.4.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen J. 2nd ed. Erlbaum; New York: 1988. Statistical Power Analyses for the Behavioral Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schoenfeld B.J., Pope Z.K., Benik F.M. Longer interset rest periods enhance muscle strength and hypertrophy in resistance-trained men. J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30:1805–1812. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000001272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marcolin G., Petrone N., Moro T. Selective activation of shoulder, trunk, and arm muscles: a comparative analysis of different push-up variants. J Athl Train. 2015;50:1126–1132. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-50.9.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lehman G.J. The influence of grip width and forearm pronation/supination on upper-body myoelectric activity during the flat bench press. J Strength Cond Res. 2005;19:587–591. doi: 10.1519/R-15024.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dhahbi W., Chaouachi A., Ben Dhahbi A. Variation of plyometric push-ups affects force application kinetics and perception of intensity. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2017;12:190–197. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2016-0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Negra Y., Chaabene H., Hammami M. Effects of high-velocity resistance training on athletic performance in prepuberal male soccer athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30:3290–3297. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000001433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]