Abstract

Objectives

Transgender individuals commonly experience barriers to quality health care and may suffer from unique musculoskeletal complaints. Although these needs are often inadequately addressed within the health care system, they could be attended to by the chiropractic community. This narrative review describes best practices for delivering culturally sensitive care to transgender patients within the context of chiropractic offices.

Methods

A literature search generated peer-reviewed material on culturally competent care of the transgender community. Google Scholar and trans-health RSS feeds on social media were also searched to find relevant gray literature. Information pertinent to a chiropractic practice was identified and summarized.

Results

Contemporary definitions of transgender, gender identity, and sexual orientation provide a framework for culturally sensitive language and clinic culture. Small changes in record keeping and office procedures can contribute to a more inclusive environment for transgender patients and improve a chiropractor’s ability to collect important health history information. Special considerations during a musculoskeletal examination may be necessary to properly account for medical and nonmedical practices transgender patients may use to express their gender. Chiropractors should be aware of health care and social and advocacy resources for transgender individuals and recommend them to patients who may need additional support.

Conclusions

Small yet intentional modifications within the health care encounter can enable chiropractors to improve the health and well-being of transgender individuals and communities.

Key Indexing Terms: Chiropractic, Transgender Persons, Cultural Competency, Quality of Health Care

Introduction

In 2016, the American Public Health Association adopted a policy advocating “the adoption and application of inclusive policies and practices that recognize and address the needs of people and communities identifying as transgender or gender nonconforming.”1 Also in 2016, the National Institute of Health formally recognized sexual and gender minorities as a health disparity population, citing evidence of discrimination and decreased access to health care.2 These barriers contribute to poorer health outcomes among transgender individuals, including a greater risk of contracting HIV and other sexually transmitted infections3, 4, 5 and of suicide,6 mental health disorders, body image and eating disorders,7 substance abuse,8 and violence.9 According to the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, 31% of respondents reported that none of their health care providers knew they were transgender.10 One in 3 reported at least 1 negative health care experience in the previous year related to being transgender. Negative experiences included verbal harassment, refusal of treatment, unnecessary or invasive questions, and the need to educate the provider about what it means to be transgender before receiving appropriate care.10 Transgressions such as these can interfere with the provision of health services and undermine the general health of a transgender person. Best practice standards of care for the transgender community are lacking; this problem is exacerbated by a dearth of research specific to this population.

As is the case with many health care professional groups,11, 12 the chiropractic profession has been criticized for the lack of diversity in both providers and patients served.13 Many chiropractors may have limited interaction with transgender individuals or communities or are not aware they interact with those who identify as transgender. This inexperience may lead to uncertainty in both communication skills and considerations for clinical care that may be unique to a transgender individual. Even well-meaning health care practitioners can be misinterpreted and may lead a transgender individual to feel unwelcome or unable to fully confide in that health care provider. Health care providers have an ethical obligation to understand how to effectively deliver culturally sensitive care for transgender patients. To date, no guidelines have been published to assist chiropractors in this area, nor have educational competencies on this topic been standardized among the chiropractic colleges. The purpose of this narrative review is to describe best practices for delivering culturally sensitive care of transgender patients within the context of chiropractic offices.

Methods

To identify existing best practices, a search was conducted in PubMed, Expanded Academic ASAP, and the Index to Chiropractic Literature to identify peer-reviewed articles related to culturally competent care of the transgender community. A search for articles written in English, with no publication date limitations, was conducted by the authors with the assistance of information specialists from the Greenawalt Library at Northwestern Health Sciences University. Key search terms were taken from known sources on the topic and included “cultural competency,” “history,” “best practices,” “transgender,” “gender,” “gender identity,” “gender identification,” and “transgender health care.” MeSH terms were derived from a PubMed MeSH search and the MeSH sections on discovered relevant articles. Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” were used to connect terms and encompass alternative phrasing for transgender persons. In addition to electronic databases, relevant gray literature was identified through Google Scholar searches and trans-health RSS feeds on social media.

Narrative reviews, best practice guidelines, professional white papers, and reports surfaced in the database searches. Position statements, recommendations, and resource information were additionally identified in the gray literature. Materials that provided recommendations for improving the care experience of transgender individuals were considered for inclusion. Information considered by the authors to be salient to conditions managed within a chiropractic office and that could influence the provision of care was also reviewed. Recommendations for treatment outside the scope of chiropractic practice were excluded from this paper.

Discussion

To effectively care for the transgender population, health care providers must understand the distinction between and definitions of gender identity and sexual orientation. A lack of understanding of these concepts is a common pitfall that can lead a patient to feel misunderstood or discriminated against. The Human Rights Campaign defines gender identity as “one’s innermost concept of self as male, female, a blend of both or neither—how individuals perceive themselves and what they call themselves.” This differs from sexual orientation, which is defined as “enduring emotional, romantic or sexual attraction to other people.”14 Gender identity and sexual orientation are 2 distinct and separate constructs; providers should be cautious to avoid assumptions that one’s gender identity influences one’s sexual orientation, and vice versa.

Transgender, then, is a gender identity term. It is used to describe individuals whose own gender identity is different from that which they were assigned at birth. This movement away from assigned gender may stem from a feeling of being part of a different gender group or the desire to move away from conventional expectations placed on gender by society.15 Although the current US Census does not collect data on gender identity, recent estimates of the transgender population in the US suggest 390 of every 100 000 adults identify as transgender.16

In the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) the diagnostic term gender identity disorder has been replaced with gender dysphoria. Gender dysphoria relates to the distress caused by a person’s assigned birth gender differing from the one with which they identify. Gender dysphoria is not considered a mental disorder and should not be treated as such. This is an important distinction from previous editions of DSM, aimed at helping avoid stigma and ensuring access to care.17 Gender dysphoria can be experienced at many different stages of being aware of individual gender variance. This may range from the recognition that one’s gender is different from that assigned at birth to an individual living full time in a manner consistent with their gender identity, possibly having undergone hormone and/or surgical treatment. These criteria are an application of American psychological health and diagnostic standards. Differing standards might apply in other countries where recognition of the transgender phenomenon could be viewed, treated, or pathologized differently.

Microaggression is a term first suggested in 1970 to describe the cumulative and summative negative effect of both overt and subtle degradations, whether intentional or unintentional, on an individual’s well-being.18 The concept was originally applied to the well-being of the African-American community and has since become more broadly attributed to the effect of these actions on additional marginalized groups, including sexual minorities.18, 19 In a 2016 American Psychological Association article, Spengler et al20 wrote, “The stigma and prejudice [marginalized groups] regularly encounter is hypothesized to lead to their significantly increased risk for developing mental health disorders.” The collective literature on microaggressions and health care supports this theory, pointing broadly toward unfavorable health outcomes, including greater risk of depression and suicide ideation among patients,19 diminished treatment effectiveness, and decreased utilization.20 Provider misuse of gender pronouns and preferred name and lack of clinical capacity to provide inclusive care should be considered microaggressions. Out of respect for all individuals and in an effort to maximize the effectiveness of care, health care providers should be conscious of what constitutes a microaggression and actively manage the clinical environment to minimize their occurrence.

Recommendations

Clinic Culture

Culturally competent care that adequately meets the social and cultural needs of transgender patients should be reflected in all aspects of a clinical encounter and engage both providers and staff. Ideally, a clinic has practice habits in place to facilitate the delivery of culturally sensitive care in a universal and systematic manner. These range from structural (eg, gender neutral restrooms) and systemic (eg, patient confidentiality protocols) considerations to intrapersonal (eg, evaluating your belief systems) and interpersonal (eg, trusting patient-provider relationships) behaviors.21, 22 A list of clinical considerations are highlighted next, with suggestions for improvements specific to serving transgender patients within a chiropractic office.

Written and Verbal Communication

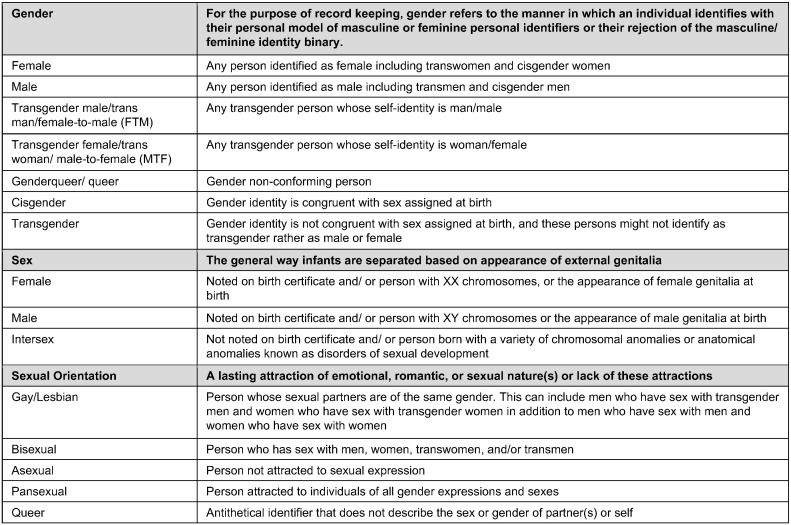

The words we choose as health care providers should be considered carefully to avoid discrimination and to create a culture of inclusivity, understanding, and confidence. Figure 1 includes a list of terminology that may facilitate understanding of and communication about gender variance. It is important to note that the language used within the transgender community continues to evolve in ways that contemporarily reflect identity and a range of experiences of transgender individuals. One example is use of the term gender affirmation to replace gender reassignment. The former conveys a more positive connotation of treatment that is aimed at supporting the individual’s true identity. Another example is the reclamation of the once pejorative label queer, which is currently used as a neutral identifier of sexuality and gender. Although evolving language within the transgender community can feel difficult to keep pace with, allowing individuals to self-identify and direct the terms used in their care can create a culturally sensitive lexicon customized to individual patient needs.

Fig 1.

Adapted Glossary of Recordkeeping Terms.31

Self-identification, including preferred name and preferred pronoun, should be directed by patients to ensure their agency in the health care encounter. Registration or intake forms can include fields for patients to disclose this information alongside their legal name, date of birth, and other initial demographic information. It is important that all staff take note of preferred name and pronoun and use them to address patients in this manner throughout the clinical encounter. It is increasingly common for individuals who have a nonbinary gender identity to use they or them as their pronoun. Note that transgender patients’ insurance paperwork or medical records from other offices may not reflect the name or gender with which your patient currently identifies and thus require additional communication.

Record Keeping

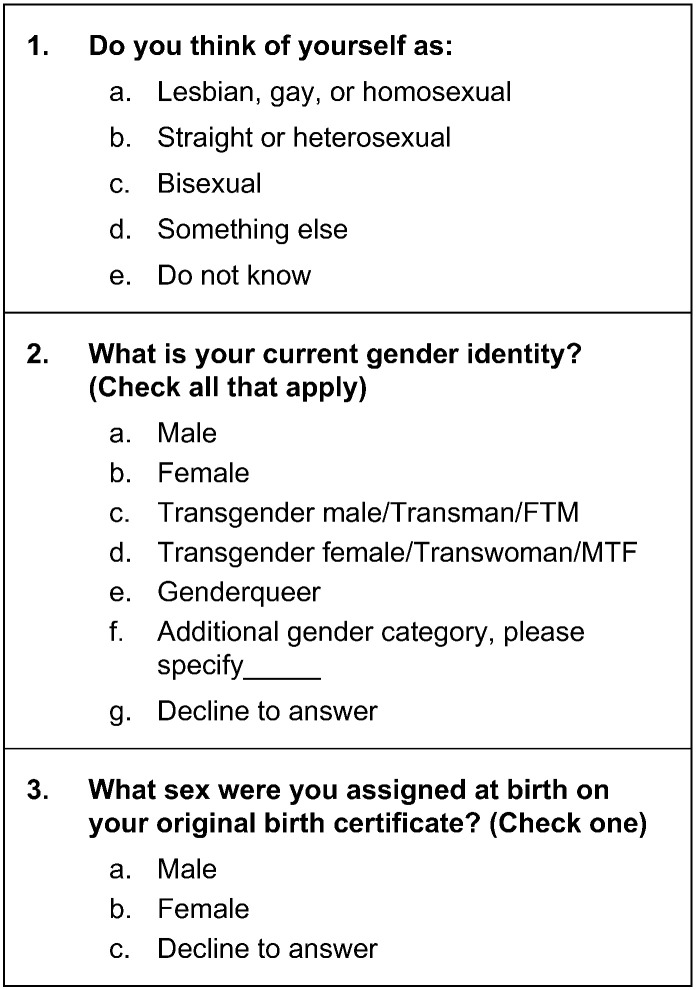

Meaningful Use certified electronic health record software is required to include sexual orientation and gender identity data fields.23 Patient questions and responses have been standardized under the advisement of the Fenway Institute and the Institute of Medicine and are provided in Figure 2. In a study by Cahill et al,24 conducted across 4 clinic settings, intake questionnaires addressing gender identity, sex, and sexual orientation were found to be acceptable by both heterosexual and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients. Furthermore, respondents expressed support for implementation of these questions and acknowledged their importance from a clinical perspective.24 Providers may want to consider using the questions and response categories in Figure 2 to improve the accuracy of patient records on sexual orientation and gender identity.

Fig 2.

Suggested Patient Intake Questions.32

History

Although the chiropractic health care needs of transgender individuals may be characterized as similar to other patients seen in practice, clinicians should additionally consider risk factors and concerns unique to the transgender community. Comprehensive patient exams require differential diagnoses based on the specific anatomy of the individual, bearing in mind that persons may have a combination of sex characteristics and organs. For example, discussion of preventative cancer screening should be related to organs and hormone-influenced tissues the transgender patient has at the time of evaluation.

Transgender patients may be particularly sensitive to questions regarding lifestyle and sexuality because of past discrimination. It is important to avoid stereotypes regarding sexual orientation, relationship status, or pregnancy status based on gender expression alone. Open-ended questions such as, “Are you currently involved in a sexual relationship?” “How would you describe your sexual activity?” or “Do you have any sexual concerns that you would like to discuss?” can be used to assess sexual activity. Counseling should focus on health promotion and safety in a nonjudgmental manner.25 Similar to any patient, a transgender individual’s risk for sexually transmitted infection depends on known risk factors for all populations. These include unprotected sexual behavior, substance abuse in conjunction with sexual behavior, violence, and multiple sexual partners.26 As with any patient, it is important to affirm that personal moral, religious, or cultural belief systems should remain independent from the provision of health care to transgender individuals.

Musculoskeletal Evaluation

Special considerations may be required to adequately and accurately conduct a musculoskeletal health assessment in transgender patients. Transgender individuals commonly incorporate nonmedical practices to express their gender. These may include padding or use of prostheses, penile tucking, or postural changes to conceal stature or secondary sex characteristics. For example, a female-to-male (FTM) person may use posture to attempt to minimize the appearance of breasts. Postural analyses may subsequently reveal upper-crossed syndrome, including rounded shoulders, anterior head carriage, weakened posterior, and shortened anterior neck and thoracic muscles.

Binders and other compression garments are often used to compress and conceal breast tissue. According to 1 survey of 1800 transgender individuals assigned female sex at birth, 52% reported daily binding, with 97% of those reporting at least 1 negative side effect of the practice. Symptoms most commonly included chest, shoulder, and back pain; lightheadedness or dizziness; shortness of breath; and dermatological issues (eg, itch, rash, or acne).27 Chiropractors should inquire about binding practices in transmasculine patients. Empirical evidence suggests that taking regular days off from binding could potentially reduce negative health effects. It is important to note that, although binding is associated with side effects, it is also associated with improved emotional well-being and less anxiety and dysphoria-related depression.27 Physical harm should be weighed against patient preferences and the positive psychological benefit of a binding practice to devise a suitable treatment plan.

Hormone therapy is common among transitioning transgender patients. Examples include estrogen and antiandrogen therapy for male-to-female (MTF) patients and testosterone therapy for FTM patients. Other individuals, including gender nonconforming, nonbinary, and genderqueer persons, may be prescribed hormone therapy. For the purpose of illustrating cross-sex physiological implications, references to persons whose transition is binary in nature are meant to include those who do not share this identity. Hormone therapy can present a range of possible side effects, including some that affect the musculoskeletal system. Cross-sex hormone therapy has been reported to increase body weight in both sexes, with a gain in body fat and decrease in lean body mass among MTF individuals and the opposite effects among FTM individuals.28 This may influence not only body habitus but also risk of cardiovascular disease. Epidemiologic research suggests that long-term hormone use may result in an increased risk of osteoporosis among MTF persons.29 Bone density screening has been recommended on FTM patients beginning at age 50 if taking testosterone for more than 10 years and at age 60 if on testosterone for a shorter duration. Bone density screening is not recommended for MTF patients on hormone therapy.30 There are conflicting reports on potential risk of tendon rupture with testosterone therapy; FTM patients who use testosterone and are beginning exercise or weight training programs may be well advised to increase activity gradually. Anecdotal evidence suggests the occurrence of hormone injection site granulomas or calcifications, which occur when a substance is inadvertently injected into fat and not muscle. These may be palpated in a soft tissue exam or detected radiographically. If symptomatic, injection granulomas are typically treated with injected corticosteroids or excised.

Resources and Advocacy

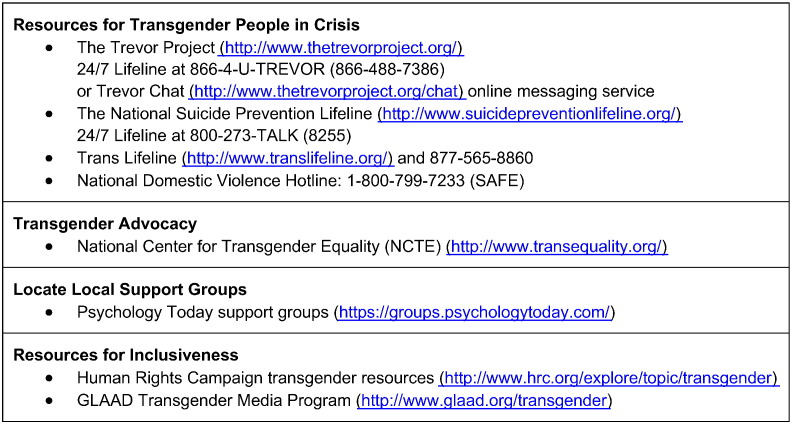

It is important for providers to recognize their limitations in terms of providing care for individuals who may need additional support or social services. A wide range of tools and resources are available from nonprofit organizations to help support your care of transgender patients. Figure 3 provides information for national resources. Providers are well advised to also maintain a list of local providers across health care disciplines with welcoming and transgender-affirming practices.

Fig 3.

Transgender Support Services.

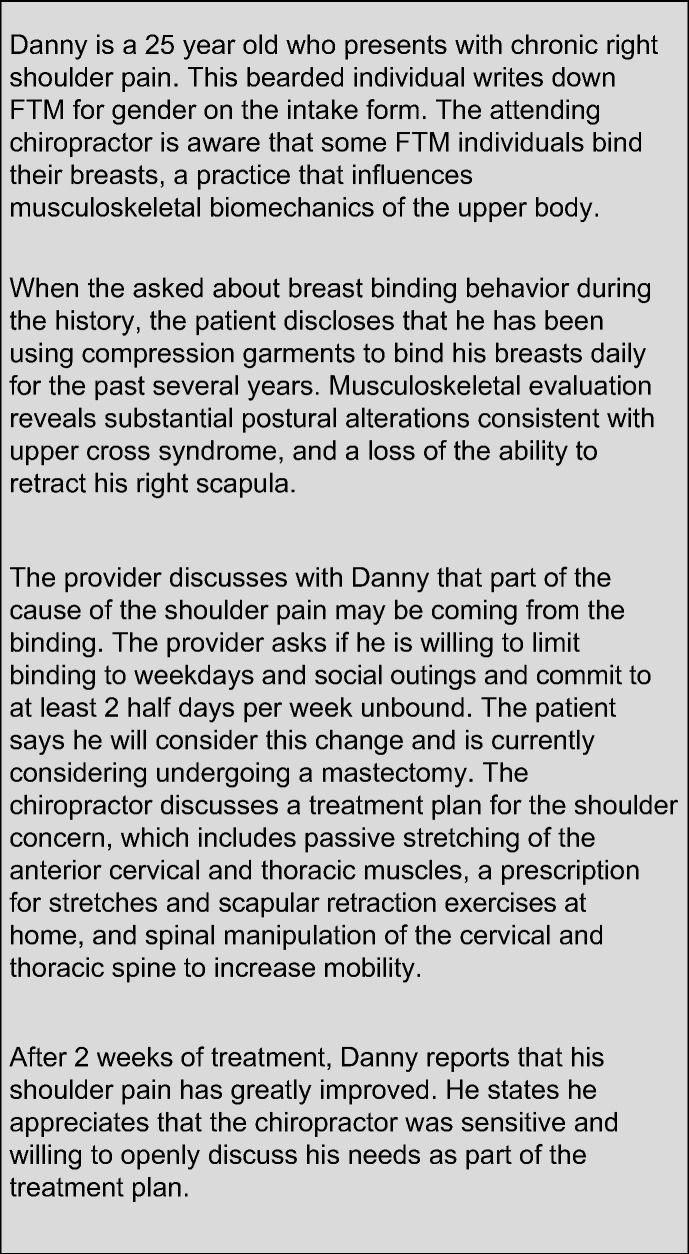

Responsiveness to the unique perspectives and needs of transgender patients can facilitate trust and enhance the therapeutic encounter. Increased exposure to transgender communities and clinical cases (Fig. 4) may facilitate competency in the provision of care in this population. Further, refinement of clinical systems, processes, and skills should be considered an ongoing process.

Fig 4.

Clinical Vignette.

Conclusion

An increased awareness of transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals and communities can reduce barriers to care and engender an office environment that is welcoming to all individuals. Small yet intentional modifications to the clinical encounter can improve a chiropractor’s ability to meet the unique needs of a transgender patient, supporting both musculoskeletal health specifically and general well-being more broadly. Culturally sensitive adaptations apply to clinic culture, written and verbal communication, record keeping, history taking, musculoskeletal evaluation, and access to referral partners and agencies when necessary. As best practices for the care of transgender patients continue to evolve, so too should chiropractic practice, research, and education continue to strive toward culturally competent care.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

No funding sources or conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

Contributorship Information

Concept development (provided idea for the research): M.M., W.K.F., H.H.D.

Design (planned the methods to generate the results): M.M., W.K.F., H.H.D.

Supervision (provided oversight, responsible for organization and implementation, writing of the manuscript): M.M.

Data collection/processing (responsible for experiments, patient management, organization, or reporting data): M.M.

Analysis/interpretation (responsible for statistical analysis, evaluation, and presentation of the results): M.M.

Literature search (performed the literature search): M.M., W.K.F., H.H.D.

Writing (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript): M.M., W.K.F., H.H.D.

Critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content, this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking): M.M., W.K.F., H.H.D.

Practical Applications

-

•

Soliciting and using patients’ preferred name and pronoun contributes to a culturally sensitive clinic environment.

-

•

Sexual orientation and gender identity questions on patient intake forms should be designed to capture a range of responses.

-

•

A comprehensive history of transgender patients includes assessment of known risk factors among transgender populations and differential diagnosis based on the specific anatomy of the individual.

-

•

Musculoskeletal evaluation may include special considerations like hormone therapy, postural alterations to conceal secondary sex characteristics, and binding practices.

Alt-text: Image 1

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge Krista Jacobson, Public Services Librarian at Northwestern Health Sciences University, for expertise and assistance with the literature search, and Michael J. Morris, PhD, at Denison University, for critique of the cultural sensitivity of this manuscript.

References

- 1.American Public Health Association (APHA) Promoting transgender and gender minority health through inclusive policies and practices (20169) 2016. https://apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2017/01/26/promoting-transgender-and-gender-minority-health-through-inclusive-policies-and-practices Available at: Accessed April 1, 2017.

- 2.Pérez-Stable EJ, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Director’s message: Sexual and gender minorities formally designated as a health disparity population for research purposes. 2016. https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about/directors-corner/message.html Available at: Accessed April 1, 2017.

- 3.Wood SM, Salas-Humara C, Dowshen NL. Human immunodeficiency virus, other sexually transmitted infections, and sexual and reproductive health in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender youth. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2016;63(6):1027–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2016.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garofalo R, Deleon J, Osmer E, Doll M, Harper GW. Overlooked, misunderstood and at-risk: exploring the lives and HIV risk of ethnic minority male-to-female transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(3):230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson EC, Garofalo R, Harris DR, Belzer M. Sexual risk taking among transgender male-to-female youths with different partner types. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(8):1500–1505. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.160051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Testa RJ, Michaels MS, Bliss W, Rogers ML, Balsam KF, Joiner T. Suicidal ideation in transgender people: Gender minority stress and interpersonal theory factors. J Abnorm Psychol. 2017;126(1):125–136. doi: 10.1037/abn0000234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McClain Z, Peebles R. Body Image and eating disorders among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2016;63(6):1079–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Talley AE, Gilbert PA, Mitchell J, Goldbach J, Marshall BD, Kaysen D. Addressing gaps on risk and resilience factors for alcohol use outcomes in sexual and gender minority populations. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2016;35(4):484–493. doi: 10.1111/dar.12387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calton JM, Cattaneo LB, Gebhard KT. Barriers to help seeking for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer survivors of intimate partner violence. Trauma Violence Abus. 2016;17(5):585–600. doi: 10.1177/1524838015585318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. National Center for Transgender Equality; Washington, DC: 2016. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Relf MV. Advancing diversity in academic nursing. J Prof Nurs. 2016;32(suppl 5):S42–S47. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell DA, Lassiter SL. Addressing health care disparities and increasing workforce diversity: the next step for the dental, medical, and public health professions. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2093–2097. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.082818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young KJ. Overcoming barriers to diversity in chiropractic patient and practitioner popultations: A commentary. J Cult Divers. 2015;22(3):82–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Human Rights Campaign. Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Definitions. Available at: http://www.hrc.org/resources/sexual-orientation-and-gender-identity-terminology-and-definitions Accessed April 2017.

- 15.Stryker S. Seal Press; Berkeley, CA: 2008. Transgender History. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meerwijk EL, Sevelius JM. Transgender population size in the United States: a meta-regression of population-based probability samples. Am J Public Heal. 2017;107(2):e1–e8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Psychiatric Association . 2013. What is Gender Dysphoria? Available at: https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/gender-dysphoria/what-is-gender-dysphoria Accessed April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sue DW. John Wiley & Sons; New Jersey, NJ: 2010. Microaggressions in everyday life: race, gender, and sexual orientation. [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Keefe V.M., Wingate L.R., Cole A.B., Hollingsworth D.W., Tucker R.P. Seemingly harmless racial communications are not so harmless: Racial microaggressions lead to suicidal ideation by way of depression symptoms. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2015;45(5):567–576. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spengler ES, Miller DJ, Spengler PM. Microaggressions: Clinical errors with sexual minority clients. Psychotherapy (Chic) 2016;53(3):360–366. doi: 10.1037/pst0000073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilkerson JM, Rybicki S, Barber CA, Smolenski DJ. Creating a culturally competent clinical environment for LGBT patients. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2011;23(3):376–394. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coren JS, Coren CM, Pagliaro SN, Weiss LB. Assessing your office for care of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients. Health Care Manag (Frederick) 2011;30(1):66–70. doi: 10.1097/HCM.0b013e3182078bcd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cahill SR, Baker K, Deutsch MB, Keatley J, Makadon HJ. Inclusion of sexual orientation and gender identity in stage 3 meaningful use guidelines: A huge step forward for LGBT health. LGBT Health. 2016;3(2):100–102. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2015.0136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cahill S, Singal R, Grasso C. Do ask, do tell: High levels of acceptability by patients of routine collection of sexual orientation and gender identity data in four diverse American community health centers. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e107104. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Association of Reproductive Health Professionals Talking to patients about sexuality and sexual health. http://www.arhp.org/uploadDocs/SHF_Talking.pdf Available at: Accessed April 2017.

- 26.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Healthy People 2020. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/sexually-transmitted-diseases. Accessed April 2017.

- 27.Peitzmeier S, Gardner I, Weinand J, Corbet A, Acevedo K. Health impact of chest binding among transgender adults: a community-engaged, cross-sectional study. Cult Health Sex. 2017;19(1):64–75. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2016.1191675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klaver M, Dekker MJHJ, de Mutsert R, Twisk JWR, den Heijer M. Cross-sex hormone therapy in transgender persons affects total body weight, body fat and lean body mass: a meta-analysis. Andrologia. 2017;49(5):e12660. doi: 10.1111/and.12660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wierckx K, Mueller S, Weyers S. Long-term evaluation of cross-sex hormone treatment in transsexual persons. J Sex Med. 2012;9(10):2641–2651. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fenway Health. 2015. The Medical Care of Transgender Persons. Boston, MA: Fenway Health. [Google Scholar]

- 31.University of California SF Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Resource Center. General Definitions. Available at: https://lgbt.ucsf.edu/glossary-terms. Accessed April 2017.

- 32.Fenway Institute, the Center for American Progress, the Mayo Clinic, and several other health care, research, professional, and patient advocacy organizations . 2015. Public Comment on draft Interoperability Standards Advisory. Available at: http://doaskdotell.org/wp-content/uploads/Public-Comment-Interoperability-Standards-Advisory-comments-050115.pdf. Accessed April 2017. [Google Scholar]