Abstract

From the eighth century onward, the Indian Ocean was the scene of extensive trade of sub-Saharan African slaves via sea routes controlled by Muslim Arab and Swahili traders. Several populations in present-day Pakistan and India are thought to be the descendants of such slaves, yet their history of admixture and natural selection remains largely undefined. Here, we studied the genome-wide diversity of the African-descent Makranis, who reside on the Arabian Sea coast of Pakistan, as well that of four neighboring Pakistani populations, to investigate the genetic legacy, population dynamics, and tempo of the Indian Ocean slave trade. We show that the Makranis are the result of an admixture event between local Baluch tribes and Bantu-speaking populations from eastern or southeastern Africa; we dated this event to ∼300 years ago during the Omani Empire domination. Levels of parental relatedness, measured through runs of homozygosity, were found to be similar across Pakistani populations, suggesting that the Makranis rapidly adopted the traditional practice of endogamous marriages. Finally, we searched for signatures of post-admixture selection at traits evolving under positive selection, including skin color, lactase persistence, and resistance to malaria. We demonstrate that the African-specific Duffy-null blood group—believed to confer resistance against Plasmodium vivax infection—was recently introduced to Pakistan through the slave trade and evolved adaptively in this P. vivax malaria-endemic region. Our study reconstructs the genetic and adaptive history of a neglected episode of the African Diaspora and illustrates the impact of recent admixture on the diffusion of adaptive traits across human populations.

Keywords: population genetics, admixture, South Asia, slave trade, African diaspora, DARC, FY, Duffy blood group, Plasmodium vivax malaria, post-admixture selection

Main Text

The trade of slaves has existed in many cultures since early human history and has left a profound legacy on the social, cultural, and genetic diversity of human populations. Over the last five centuries, more than ten million slaves were transported from Africa to the New World by western European traders.1 The ancestry of African slaves captured for the transatlantic slave trade has been extensively studied with the use of rich historical records2, 3 and genome-wide surveys of present-day African Americans.4, 5, 6 However, much less is known about the populations who were enslaved for the Indian Ocean slave trade.7 From the 8th to the 19th centuries, about four million people were captured from the shores of eastern Africa by Arab Muslim and Swahili traders. It has been suggested that slaves transported before the 16th century originated from the Horn of Africa, i.e., Nilotic or Afro-Asiatic speakers from present-day Ethiopia, whereas most Africans enslaved from the 18th century onward were Zanj,8 i.e., Bantu speakers of southeastern Africa. Indeed, the Omani Empire progressively imposed their domination on the Swahili coast and Zanzibar in this time period, leading to an intensified slave trade from these regions. However, direct evidence of the provenance of the African slaves embarked for the Indian Ocean trade remains lacking.

A few present-day populations in South Asia, including the Siddis from western India and the Makranis from Pakistan, are considered to descend from African slaves.9 Because these populations have not preserved their original African languages and traditions, except perhaps musical culture,10 studying the genome of South Asian populations of African descent represents a unique opportunity to increase our knowledge about the dynamics and tempo of the Indian Ocean slave trade. Genetic studies of both uniparentally inherited and autosomal markers have estimated that the Siddis have 60%–75% sub-Saharan African genetic ancestry and carry Y chromosome haplogroups characteristic of Bantu-speaking populations.11, 12 By contrast, the African ancestry of the Makranis is limited to 12% (±7%) for the Y chromosome and 40% (±9%) for mtDNA.13, 14 Nevertheless, most of these estimations are based on uniparentally inherited markers, which provide a partial, sex-biased view of past population history, and no studies have appropriately investigated the ancestry sources of African-descent admixed populations in South Asia. Furthermore, their study can inform the extent to which traits that were adaptive in parental populations, such as increased resistance to infection, have contributed to the fitness of admixed populations in a different environmental context.15

In this study, we aimed to increase our knowledge of the geographic origins, admixture dynamics, and post-admixture selection processes of South Asian African-descent populations that originated from the Indian Ocean slave trade by using a population-genomics approach. To address these questions, we genotyped 118 individuals from five Pakistani populations on the Illumina Omni2.5 array (Figure S1). We excluded 16 individuals who presented with evidence of cryptic relatedness (i.e., kinship coefficient > 0.025 and an identical-by-state statistic < 0.034 estimated from SNP array data with KING16), leading to a total of 102 unrelated individuals who were retained for all subsequent analyses. These included 24 African-descent Makranis sampled from different locations near Karachi and on the Makran coast (here referred to as Makranis), 22 Baluch inhabiting the Makran coast (here referred as Makrani Baluch), 22 Baluch and 18 Brahui from Baluchistan, and 16 Parsi from Karachi, in the Sindh province of Pakistan (Table S1). It is important to note that our sample of African-descent Makranis is distinct from the so-called Makrani of the HGDP-CEPH panel.17, 18 The latter correspond to our Makrani Baluch, who are not considered to descend from African slaves and present with neither anthropological nor cultural features associated with African ancestries.19 DNA sampling has been described elsewhere.13, 14 Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study was approved by the Institut Pasteur (institutional review board no. 2011-54/IRB/6). After standard quality-control filters (Figure S1), a total of 2,263,423 SNPs were retained for subsequent analyses. We merged the newly generated data with relevant, available datasets, including those of the HapMap 3 International Consortium20 and the African Genome Variation Project,21 yielding a total of 1,316 individuals genotyped for 1,356,632 SNPs (Table S1).

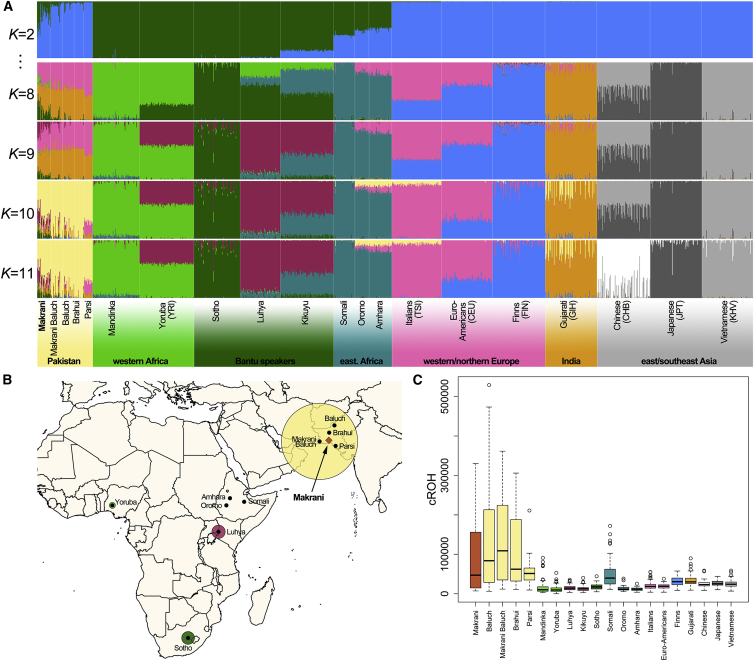

Unsupervised ADMIXTURE analysis22 estimated that the Makranis are composed of 25.5% ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa and 74.5% from Pakistan, with a standard deviation (SD) of 16.6% (Figures 1A, S2, and S3; Table S2). The large inter-individual variance in African ancestry among the Makranis is suggestive of recent admixture.23 We also observed varying levels of African ancestry among the remaining Pakistani populations: 6.7% (SD = 10.7%) in the neighboring Makrani Baluch, followed by a baseline of 1%–2% in the Baluch and Brahui of Baluchistan and the Parsi from Karachi. With increased K values in the ADMIXTURE analysis, the African ancestry of the Makranis appeared to be related to that of Bantu-speaking populations from eastern or southeastern Africa, more than that of western or Horn of Africa populations (Figure 1A). We obtained comparable results when merging our newly generated data with two independent datasets that together included 1,111 individuals from 63 worldwide populations but a limited number of SNPs (226,323 SNPs common to all datasets; Figures S4 and S5; Table S1).6, 17

Figure 1.

African Origins and Levels of Parental Relatedness of the Admixed Makranis of Pakistan

(A) Clustering analysis was performed on 1,316 individuals and 819,671 independent SNPs (i.e., 1,356,632 SNPs were LD pruned for SNPs with r2 > 0.5; Figure S1) with ADMIXTURE.22 The K value providing the lowest cross-validation error was K = 8 (Figure S2). For each K value, the most supported result across ten iterations is shown. Results for other K values are shown in Figure S3.

(B) Circle sizes are proportional to the genetic contributions of possible source populations to the Makranis, estimated with GLOBETROTTER18 on the basis of 16 individuals per source population and 1,356,632 SNPs.

(C) Cumulative runs of homozygosity (cROHs) in the Makranis and other worldwide populations.

To formally test whether the Makranis are the result of an admixture event and, if so, to determine when such admixture occurred and which populations were involved, we phased the data with SHAPEIT224 and used the haplotype-based GLOBETROTTER approach.18, 25 Admixture linkage-disequilibrium (LD) decay fitted well with expectations under a single admixture event (simulation-based p < 0.01; Figure S6) occurring 300 ± 25 years ago (12 ± 1 generations ago) between a Pakistani population (83% ancestry contribution [bootstrap 95% confidence interval (CI) of the parameter estimate = 82%–84%]) and a sub-Saharan African population (17% ancestry contribution [95% CI = 16%–18%]). The best-matching parental populations were the Baluch (97% relative ancestry contribution [95% CI = 96%–98%] versus 3% [95% CI = 2%–4%] for the Parsi; Figure 1B) and Bantu-speaking populations from eastern or southeastern Africa (42% relative ancestry [95% CI = 10%–42%] for the Luhya of Kenya versus 40% [95% CI = 20%–44%] for the Sotho of South Africa). The contribution from the Horn of Africa, represented here by the Oromo, the Amhara, and the Somali of Ethiopia, was nil across all bootstrap replicates (Table S2). The similar contributions of eastern or southeastern Bantu-speaking groups to present-day Makranis suggest that an intermediate population, such as Mozambicans, could be the most likely unsampled source population. This hypothesis is further supported by haplotype-based principal-component (PC) analysis, which showed that the Makranis are located in an intermediate position between eastern (i.e., the Luhya) and southeastern (i.e., the Sotho) Bantu-speaking populations from PC2 to PC4 (Figure S7). These results indicate that the Makranis probably descend from slaves who were captured on the Swahili coast during the 18th century, when the Omani Empire dominated the Indian Ocean slave trade.8, 26

To learn more about endogamy and marriage practices in the Makranis, we next scanned their genomes for long runs of homozygosity (ROHs), which are indicative of elevated relatedness levels among an individual’s ancestors, even when the overall population size is large.27, 28 We detected ROHs with PLINK 1.929 by considering 1-Mb homozygous windows that included more than 20 SNPs, allowing for two heterozygous SNPs and five missing genotypes.30 The mean cumulative ROH in the Makranis was large and not significantly different from that observed in the other Pakistani populations (two-sample t test adjusted p > 0.05; Figure 1C), who are among the studied populations with the largest levels of parental relatedness worldwide.28 Notably, we found no significant correlation between cumulative ROHs and Pakistani ancestry in the Makranis (Spearman’s ρ = 0.25, p = 0.24), suggesting that their levels of homozygosity are not simply due to identity by descent in the Pakistani fraction of their genomes. Although future studies with increased sample sizes are needed to confirm this hypothesis, our results suggest that the descendants of African slaves in Pakistan rapidly adopted the local practices of endogamy.19

We next evaluated whether heritable traits that are known to be adaptive in humans and that were brought by African slaves have also conferred a selective advantage in the South Asian environment after the admixture event and led to signatures of post-admixture selection in the Makranis. Specifically, we tested whether variants associated with skin pigmentation (MIM: 227220),31 lactose tolerance (MIM: 223100),32 and host resistance to malaria (MIM: 611162)33 show departures from their expected frequency under an admixture model15 and/or an excess of local African ancestry in the Makrani genomes.6, 34, 35 We genotyped 18 candidate variants by using TaqMan assays and two variants in the LCT (MIM: 603202) regulatory region by using Sanger sequencing (Figure S1); all were absent from the Omni2.5 SNP array (Table 1).

Table 1.

Tests for Post-admixture Selection for 20 Candidate Variants in the Makranis

| Variant | Position (GRCh37a) | HUGO Gene Name (MIM No.) | Candidate Allele | Alternative Allele | Luhya | Brahui | Parsi | Baluch | Makrani Baluch | Makrani (Obs.) | Makrani (Exp.) | p Value (Binomial Test) | Local Ancestry | SD from Average | p Value (PCAdapt) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dark Skin Pigmentation | |||||||||||||||

| rs1426654 | chr15: 48,426,484 | SLC24A5 (609802) | G | A∗ | 0.92 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 1.0 | 0.17 | −0.71 | 3.0 × 10−3 |

| rs6058017 | chr20: 32,856,998 | ASIP (600201) | G | A∗ | 0.76 | 0.16 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.37 | 0.13 | 0.19 | −0.43 | 0.92 |

| rs2228478 | chr16: 89,986,608 | MC1R (155555) | G | A∗ | 0.57 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.27 | 0.30 | 0.23 | 0.30 | 0.20 | −0.28 | 0.12 |

| rs2287499 | chr17: 7,592,168 | WRAP53 (612661) | G | C∗ | 0.86 | 0.41 | 0.19 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.77 | 0.27 | 0.71 | 0.04 |

| rs2467737 | chr15: 43,737,188 | TP53BP1 (605230) | A | G∗ | 0.95 | 0.59 | 0.46 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.59 | 0.48 | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.71 | 2.5 × 10−4 |

| rs642742 | chr12: 89,299,746 | KITLG (184745) | T | C∗ | 0.91 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 1.0 | 0.23 | 0.14 | 2.6 × 10−3 |

| rs16891982 | chr5: 33,951,693 | SLC45A2 (606202) | C | G∗ | 0.99 | 0.78 | 0.58 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.93 | 0.05 | 0.10 | −1.71 | 0.07 |

| rs26722 | chr5: 33,963,870 | SLC45A2 (606202) | C | T∗ | 0.95 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.69 | 0.75 | 0.81 | 0.76 | 0.50 | 0.10 | −1.71 | 0.53 |

| rs1667394 | chr15: 28,530,182 | OCA2 (611409), HERC2 (605837) | C | T∗ | 0.97 | 0.61 | 0.69 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.62 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.04 |

| rs1800404 | chr15: 28,235,773 | OCA2 (611409), HERC2 (605837) | C | T∗ | 0.91 | 0.47 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.66 | 0.56 | 0.58 | 0.77 | 0.27 | 0.71 | 0.58 |

| rs1042602 | chr11: 88,911,696 | TYR (606933) | C | A∗ | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.83 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.66 | 0.19 | −0.43 | 0.14 |

| rs9782955 | chr1: 236,039,877 | LYST (606897) | C | T∗ | 0.95 | 0.75 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.82 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.37 | 0.15 | −1.00 | 0.72 |

| rs3829241 | chr11: 68,855,363 | TPCN2 (612163) | G | A∗ | 0.97 | 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.78 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.83 | 0.56 | 0.23 | 0.14 | 0.51 |

| rs12896399 | chr14: 92,773,663 | SLC24A4 (609840) | G | T∗ | 0.98 | 0.69 | 0.66 | 0.81 | 0.66 | 0.81 | 0.85 | 0.41 | 0.23 | 0.14 | 0.34 |

| Lactose Tolerance | |||||||||||||||

| rs145946881 | chr2: 136,608,746 | LCT (603202) | G∗ | C | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.629 | 0.21 | −0.14 | NA |

| rs4988235 | chr2: 136,608,646 | LCT (603202) | A∗ | G | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.624 | 0.21 | −0.14 | 8.5 × 10−3 |

| Malaria Resistance | |||||||||||||||

| rs2814778 | chr1: 159,174,683 | ACKR1, also known as DARC (613665) | C∗ | T | 1.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.30 | 0.0055 | 0.44 | 3.13 | 2.3 × 10−7 |

| rs17047661 | chr1: 207,782,889 | CR1 (120620) | G∗ | A | 0.70 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.190 | 0.25 | 0.43 | 1.1 × 10−3 |

| rs334 | chr11: 5,248,232 | HBB (141900) | A∗ | T | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.633 | 0.23 | 0.14 | NA |

| rs2213169 | chr11: 5,303,063 | HBE1 (142100) | A∗ | G | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.724 | 0.23 | 0.14 | NA |

Derived alleles are indicated by an asterisk. Observed (obs.) frequencies of candidate alleles are shown together with those expected (exp.) in the Makranis according to their inferred admixture model. Local ancestry at candidate variants, as well as the corresponding number of standard deviations (SDs) from the genome-wide average, was obtained with RFMix 1.5.4.36 NA stands for not applicable.

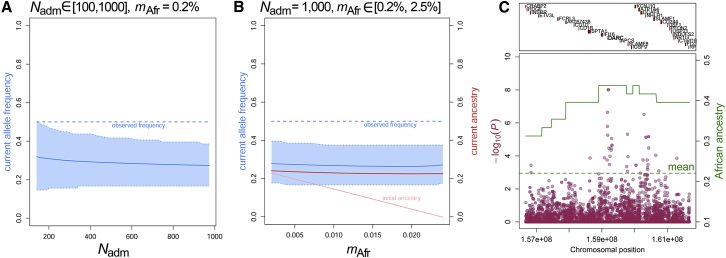

UCSC Genome Browser hg19.

A single variant, rs2814778 in DARC (Duffy antigen receptor for chemokines, more recently termed ACKR1 for atypical chemokine receptor 1 [MIM: 613665]), showed several consistent signals of post-admixture selection (Figure 2). This variant is responsible for the Duffy-null blood group, which is thought to confer complete resistance to Plasmodium vivax malaria.33 The derived C allele, which reaches near fixation in sub-Saharan Africa and is largely absent from Eurasia,38 was detected at a significantly higher frequency in the Makranis (50%) than expected (30%; adjusted binomial test p = 5.5 × 10−3) given its frequency in the parental populations and admixture proportions estimated by ADMIXTURE (Table S2). This signal was confirmed by 100,000 simulations under the Wright-Fisher neutral model and the assumption of realistic effective population sizes of the Makranis and migration rates from parental populations (simulation-based p < 0.05; Figures 2A and 2B). The rs2814778 variant was strongly differentiated between the Makranis and non-admixed Baluch (p = 2.3 × 10−7; Figure 2C).37 Furthermore, African local ancestry along the genome of the Makranis, inferred by RFMix v.1.5.4,36 reached 44% in the DARC genomic region, 3.13 SDs above the genome-wide average of 22% (Figure 2C; Table S2), indicating that the signal of selection extends to surrounding linked markers. Finally, the C allele was also observed at 25% in the Makrani Baluch (Table 1), whereas their African ancestry was only ∼7% (Table S2), suggesting that the variant was also positively selected in Pakistani populations with more limited African ancestry. Together, these results suggest that the Duffy-negative blood group has been under post-admixture selection in South Asia, where 80% of individuals with severe malaria are infected by P. vivax.39

Figure 2.

Evidence of Post-admixture Selection of the Duffy-Null Blood Group in Pakistan

(A and B) Simulation-based evidence for post-admixture selection of the Duffy-null blood group in the Makranis. We performed 100,000 Wright-Fisher simulations of an admixed population resulting from admixture occurring 12 generations ago (A) by using an effective population size (Nadm) ranging from 100 to 1,00015 and assuming a fixed, low migration rate (mAfr) of 0.2%, corresponding to the proportion of the admixed population that is replaced by individuals from the African parental population at each generation; or (B) by using a fixed Nadm of 1,000 and a mAfr ranging from 0.2% to 2.5%. The dashed blue line indicates the observed allele frequency in the Makranis, and the blue area represents the 95% quantile of the distribution of simulated allele frequencies in a sample of 24 individuals. The light-pink line shows the initial, simulated African ancestry in the admixed population, and the red line shows the final African ancestry (in the last generation). We tuned the initial African ancestry so that the final ancestry fit that estimated by ADMIXTURE.

(C) Local signatures of post-admixture selection in the Makranis. The green line indicates the average African local ancestry inferred by RFMix v.1.5.436 with two expectation-maximization steps. Maroon points indicate −log10(p values) of PCAdapt,37 which tested for strong genetic differentiation between the Makranis and non-admixed Baluch.

This study reconstructs the recent genetic and adaptive history of the descendants of African slaves carried by the Indian Ocean trade, a major yet neglected episode of the African Diaspora. Oral traditions suggest that the Makranis descend from Abyssinian (i.e., present-day Ethiopian) slaves who were transported to Pakistan in the 8th century.40 Our genomic survey indicates instead that most of their African ancestry can be traced back to the so-called Zanj, i.e., Bantu-speaking populations from the Swahili coast. Exhaustive sampling of southeastern Bantu-speaking populations will now be needed to further narrow the geographic origins of the African ancestors of Makrani populations. Despite this potential limitation, the Swahili coastal origin of African slaves is further supported by the estimated date of admixture between the African and Pakistani ancestors of the Makranis in the beginning of the 18th century, a period when the majority of slaves were captured in southeast Africa under the rule of the Omani Empire.8, 26 Furthermore, we identified the Baluch as their best-matching source of Pakistani ancestry; Baluch men were historically recruited into the slave trade as soldiers, body guards, and sailors for Omani Muslims mainly during the 18th and 19th centuries.19 Our results do not necessarily imply that the Indian Ocean slave trade to Pakistan developed only in this time period, given that the arrival of slaves might not have been accompanied by immediate admixture with local populations. Furthermore, estimating the admixture time on the basis of admixture LD decay informs the period during which the bulk of admixture occurred and can be biased toward more recent times when there is continuous admixture.41 Nevertheless, our analyses do not support a scenario of admixture mostly occurring in the 8th century, as suggested by oral traditions, and suggest instead that the genetic legacy of African slaves in present-day Pakistanis is of more recent origin.

It is also important to highlight that we detected unexpectedly low African ancestry in the Makranis (17%) in relation to that estimated in the African-descent Siddis from India (>60%).12 Two hypotheses can be put forward to explain this finding: the number of African slaves transported to present-day Pakistan might have been lower than that transported to India, or genetic isolation of African slaves (i.e., segregation) might have been stronger in India than in Pakistan, where co-habitation and intermarriages with slaves were commonly practiced. Consistently with the latter scenario, historical records suggest that female slaves had more chances to intermix with local South Asian populations than male slaves,26 and genetic analyses suggest that the majority of African slaves who contributed to the gene pool of present-day Pakistanis through admixture were females, whereas those admixing in India were primarily males.12, 14 Indeed, the estimated African ancestry of the Makranis from their mitochondrial genome (40%) is three times that obtained from the Y chromosome (12%), whereas it is only one-third in the Siddis (24% from mtDNA versus 70% from Y chromosome).12, 14

A seminal study has suggested that natural selection acting in the last few generations can be detected in admixed populations on the basis of signatures of post-admixture selection,15 but it has been unknown whether adaptive traits such as malaria resistance, skin pigmentation, or lactose tolerance have been selected in admixed populations of South Asia. Our data and analyses indicate that the African-specific Duffy-null blood group has evolved under post-admixture selection since it was introduced by slaves into Pakistan. The Duffy-null phenotype is caused by a variant in the DARC promoter region, which abolishes Duffy antigen protein expression on red blood cells42 and the ability of the malaria parasite P. vivax to invade erythrocytes.43 The extreme frequency differences of the Duffy-null allele between African and non-African populations were interpreted as the result of a strong selective sweep starting ∼42 kya in Africans38, 44 as a result of increased resistance to P. vivax malaria. However, P. vivax infection has been recently documented in African Duffy-null individuals,45, 46 raising the possibility that the DARC selection signature results from host resistance to another infectious agent. Given that P. vivax malaria is endemic in Pakistan,39 our results are consistent with the hypothesis that resistance to P. vivax is the main evolutionary force driving the frequency of the Duffy-null allele in admixed Pakistanis, in agreement with a genetic study of admixed Malagasy.15 Admixture mapping of malaria resistance in African-descent admixed populations living in endemic regions, such as Pakistan, could substantiate the major impact of P. vivax on the history of human adaptation.

Recent studies have provided empirical evidence that the acquisition by human populations of adaptive traits, including the response to altitude-induced hypoxia, lactase persistence, and HLA-mediated responses, has been facilitated by admixture.6, 34 Our finding of post-admixture selection targeting the Duffy-null blood group outside Africa provides evidence of adaptive admixture within our species—as opposed to interspecies adaptive introgression. Future theoretical and empirical studies of admixed populations, particularly those resulting from the African Diaspora worldwide, will provide new insights into the recent impact of natural selection on population variation in complex traits and disease susceptibility across a wide range of environmental contexts.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants who kindly accepted to provide blood samples. We thank Laure Lémée and the Eukaryote Genotyping platform (Biomics pole) from the Institut Pasteur for generating the SNP genotype raw data. This work was supported by the Institut Pasteur, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, and Agence Nationale de la Recherche grants IEIHSEER (ANR-14-CE14-0008-02), TBPATHGEN (ANR-14-CE14-0007-02), and AGRHUM (ANR-14-CE02-0003-01). C.T.S. and Q.A. were supported by the Wellcome Trust (098051).

Published: November 9, 2017

Footnotes

Supplemental Data include seven figures and two tables and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.09.025.

Contributor Information

Lluis Quintana-Murci, Email: quintana@pasteur.fr.

Etienne Patin, Email: epatin@pasteur.fr.

Accession Numbers

The newly generated SNP genotype data have been deposited in the European Genome-phenome Archive under accession number EGAS00001002558.

Web Resources

European Genome-phenome Archive, https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ega/home

OMIM, http://omim.org/

UCSC Genome Browser, https://genome.ucsc.edu/

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Lovejoy P.E. Cambridge University Press; 2000. Transformations in Slavery. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eltis D., Richardson D. Yale University Press; 2010. Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Midlo Hall G. University of North Carolina Press; 2007. Slavery and African Ethnicities in the Americas. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryc K., Durand E.Y., Macpherson J.M., Reich D., Mountain J.L. The genetic ancestry of African Americans, Latinos, and European Americans across the United States. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2015;96:37–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montinaro F., Busby G.B., Pascali V.L., Myers S., Hellenthal G., Capelli C. Unravelling the hidden ancestry of American admixed populations. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6596. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patin E., Lopez M., Grollemund R., Verdu P., Harmant C., Quach H., Laval G., Perry G.H., Barreiro L.B., Froment A. Dispersals and genetic adaptation of Bantu-speaking populations in Africa and North America. Science. 2017;356:543–546. doi: 10.1126/science.aal1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirzai B.A., Montana I.M., Lovejoy P.E. Africa World Press; 2009. Slavery, Islam and Diaspora. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vernet T. Slave trade and slavery on the Swahili coast (1500-1750) In: Mirzai B.A., Montana I.M., Lovejoy P.E., editors. Slavery, Islam and Diaspora. Africa World Press; 2009. pp. 37–76. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shihan de Silva J., Pankhurst R. African World Press; 2003. The African Diaspora in the Indian Ocean. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Badalkhan S. On the Presence of African Musical Culture in Coastal Balochistan. In: Basu H., editor. Journeys and Dwellings: Indian Ocean Themes in South Asia. Orient Longman; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Narang A., Jha P., Rawat V., Mukhopadhyay A., Dash D., Basu A., Mukerji M., Indian Genome Variation Consortium Recent admixture in an Indian population of African ancestry. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;89:111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah A.M., Tamang R., Moorjani P., Rani D.S., Govindaraj P., Kulkarni G., Bhattacharya T., Mustak M.S., Bhaskar L.V., Reddy A.G. Indian Siddis: African descendants with Indian admixture. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;89:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qamar R., Ayub Q., Mohyuddin A., Helgason A., Mazhar K., Mansoor A., Zerjal T., Tyler-Smith C., Mehdi S.Q. Y-chromosomal DNA variation in Pakistan. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;70:1107–1124. doi: 10.1086/339929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quintana-Murci L., Chaix R., Wells R.S., Behar D.M., Sayar H., Scozzari R., Rengo C., Al-Zahery N., Semino O., Santachiara-Benerecetti A.S. Where west meets east: the complex mtDNA landscape of the southwest and Central Asian corridor. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004;74:827–845. doi: 10.1086/383236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hodgson J.A., Pickrell J.K., Pearson L.N., Quillen E.E., Prista A., Rocha J., Soodyall H., Shriver M.D., Perry G.H. Natural selection for the Duffy-null allele in the recently admixed people of Madagascar. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2014;281:20140930. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.0930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manichaikul A., Mychaleckyj J.C., Rich S.S., Daly K., Sale M., Chen W.M. Robust relationship inference in genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2867–2873. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J.Z., Absher D.M., Tang H., Southwick A.M., Casto A.M., Ramachandran S., Cann H.M., Barsh G.S., Feldman M., Cavalli-Sforza L.L., Myers R.M. Worldwide human relationships inferred from genome-wide patterns of variation. Science. 2008;319:1100–1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1153717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hellenthal G., Busby G.B.J., Band G., Wilson J.F., Capelli C., Falush D., Myers S. A genetic atlas of human admixture history. Science. 2014;343:747–751. doi: 10.1126/science.1243518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicolini B. The Baluch role in the Persian gulf during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Comp. Stud. South Asia Afr. Middle East. 2007;27:384–396. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Altshuler D.M., Gibbs R.A., Peltonen L., Altshuler D.M., Gibbs R.A., Peltonen L., Dermitzakis E., Schaffner S.F., Yu F., Peltonen L., International HapMap 3 Consortium Integrating common and rare genetic variation in diverse human populations. Nature. 2010;467:52–58. doi: 10.1038/nature09298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gurdasani D., Carstensen T., Tekola-Ayele F., Pagani L., Tachmazidou I., Hatzikotoulas K., Karthikeyan S., Iles L., Pollard M.O., Choudhury A. The African Genome Variation Project shapes medical genetics in Africa. Nature. 2015;517:327–332. doi: 10.1038/nature13997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alexander D.H., Novembre J., Lange K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 2009;19:1655–1664. doi: 10.1101/gr.094052.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verdu P., Rosenberg N.A. A general mechanistic model for admixture histories of hybrid populations. Genetics. 2011;189:1413–1426. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.132787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delaneau O., Zagury J.F., Marchini J. Improved whole-chromosome phasing for disease and population genetic studies. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:5–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leslie S., Winney B., Hellenthal G., Davison D., Boumertit A., Day T., Hutnik K., Royrvik E.C., Cunliffe B., Lawson D.J., Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2. International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium The fine-scale genetic structure of the British population. Nature. 2015;519:309–314. doi: 10.1038/nature14230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicolini B. The Makran-Baluch-African Network in Zanzibar and East Africa during the XIXth Century. In: Shihan de Silva J., Angenot J.-P., editors. Uncovering the History of Africans in Asia. Brill; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.McQuillan R., Leutenegger A.L., Abdel-Rahman R., Franklin C.S., Pericic M., Barac-Lauc L., Smolej-Narancic N., Janicijevic B., Polasek O., Tenesa A. Runs of homozygosity in European populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008;83:359–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pemberton T.J., Absher D., Feldman M.W., Myers R.M., Rosenberg N.A., Li J.Z. Genomic patterns of homozygosity in worldwide human populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;91:275–292. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang C.C., Chow C.C., Tellier L.C., Vattikuti S., Purcell S.M., Lee J.J. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience. 2015;4:7. doi: 10.1186/s13742-015-0047-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henn B.M., Gignoux C.R., Jobin M., Granka J.M., Macpherson J.M., Kidd J.M., Rodríguez-Botigué L., Ramachandran S., Hon L., Brisbin A. Hunter-gatherer genomic diversity suggests a southern African origin for modern humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:5154–5162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017511108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McEvoy B., Beleza S., Shriver M.D. The genetic architecture of normal variation in human pigmentation: an evolutionary perspective and model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006;15:R176–R181. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tishkoff S.A., Reed F.A., Ranciaro A., Voight B.F., Babbitt C.C., Silverman J.S., Powell K., Mortensen H.M., Hirbo J.B., Osman M. Convergent adaptation of human lactase persistence in Africa and Europe. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:31–40. doi: 10.1038/ng1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwiatkowski D.P. How malaria has affected the human genome and what human genetics can teach us about malaria. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2005;77:171–192. doi: 10.1086/432519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeong C., Alkorta-Aranburu G., Basnyat B., Neupane M., Witonsky D.B., Pritchard J.K., Beall C.M., Di Rienzo A. Admixture facilitates genetic adaptations to high altitude in Tibet. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3281. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schlebusch C.M., Skoglund P., Sjödin P., Gattepaille L.M., Hernandez D., Jay F., Li S., De Jongh M., Singleton A., Blum M.G. Genomic variation in seven Khoe-San groups reveals adaptation and complex African history. Science. 2012;338:374–379. doi: 10.1126/science.1227721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maples B.K., Gravel S., Kenny E.E., Bustamante C.D. RFMix: a discriminative modeling approach for rapid and robust local-ancestry inference. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;93:278–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luu K., Bazin E., Blum M.G. pcadapt: an R package to perform genome scans for selection based on principal component analysis. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2017;17:67–77. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamblin M.T., Thompson E.E., Di Rienzo A. Complex signatures of natural selection at the Duffy blood group locus. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;70:369–383. doi: 10.1086/338628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zubairi A.B., Nizami S., Raza A., Mehraj V., Rasheed A.F., Ghanchi N.K., Khaled Z.N., Beg M.A. Severe Plasmodium vivax malaria in Pakistan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013;19:1851–1854. doi: 10.3201/eid1911.130495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edlefsen J.B., Shah K., Farooq M. Makranis, the Negroes of West Pakistan. Phylon. 1960;21:124–130. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loh P.R., Lipson M., Patterson N., Moorjani P., Pickrell J.K., Reich D., Berger B. Inferring admixture histories of human populations using linkage disequilibrium. Genetics. 2013;193:1233–1254. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.147330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tournamille C., Colin Y., Cartron J.P., Le Van Kim C. Disruption of a GATA motif in the Duffy gene promoter abolishes erythroid gene expression in Duffy-negative individuals. Nat. Genet. 1995;10:224–228. doi: 10.1038/ng0695-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller L.H., Mason S.J., Clyde D.F., McGinniss M.H. The resistance factor to Plasmodium vivax in blacks. The Duffy-blood-group genotype, FyFy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1976;295:302–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197608052950602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McManus K.F., Taravella A.M., Henn B.M., Bustamante C.D., Sikora M., Cornejo O.E. Population genetic analysis of the DARC locus (Duffy) reveals adaptation from standing variation associated with malaria resistance in humans. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1006560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ménard D., Barnadas C., Bouchier C., Henry-Halldin C., Gray L.R., Ratsimbasoa A., Thonier V., Carod J.F., Domarle O., Colin Y. Plasmodium vivax clinical malaria is commonly observed in Duffy-negative Malagasy people. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:5967–5971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912496107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ryan J.R., Stoute J.A., Amon J., Dunton R.F., Mtalib R., Koros J., Owour B., Luckhart S., Wirtz R.A., Barnwell J.W., Rosenberg R. Evidence for transmission of Plasmodium vivax among a duffy antigen negative population in Western Kenya. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2006;75:575–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.