Abstract

Background

Recent efficacy studies of asthma biologics have included highly enriched patient populations. Using a similar approach, we examined factors that predict response to omalizumab to facilitate selection of patients most likely to derive the greatest clinical benefit from therapy.

Methods

Data from two phase III clinical trials of omalizumab in patients with allergic asthma were examined. Differences in rates of asthma exacerbations between omalizumab and placebo groups during the 16‐week inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) dose‐stable phase were evaluated with respect to baseline blood eosinophil counts (eosinophils <300/μL [low] vs ≥300/μL [high]) and baseline markers of asthma severity (emergency asthma treatment in prior year, asthma hospitalization in prior year, forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV 1; FEV 1 <65% vs ≥65% predicted], inhaled beclomethasone dipropionate dose [<600 vs ≥600 μg/day], and long‐acting beta‐agonist [LABA] use [yes/no]).

Results

Adults/adolescents (N = 1071) were randomized to receive either omalizumab (n = 542) or placebo (n = 529). In the 16‐week ICS dose‐stable phase, rates of exacerbations requiring ≥3 days of systemic corticosteroid treatment were 0.066 and 0.147 with omalizumab and placebo, respectively, representing a relative rate reduction in omalizumab‐treated patients of 55% (95% CI, 32%‐70%; P = .002). For patients with eosinophils ≥300/μL or with more severe asthma, this rate reduction was significantly more pronounced.

Conclusion

In patients with allergic asthma, baseline blood eosinophil levels and/or clinical markers of asthma severity predict response to omalizumab.

Keywords: asthma, biologic therapy, biomarkers, eosinophils, omalizumab

1. INTRODUCTION

Omalizumab, an anti‐immunoglobulin E (IgE) monoclonal antibody, is the first biologic therapy to be approved in the United States and European Union for the treatment of moderate to severe allergic asthma in patients who demonstrate sensitivity to a perennial aeroallergen and are ≥6 years of age.1, 2 Because asthma is a heterogeneous disease, identifying predictors of response to omalizumab may facilitate a more precise approach to treatment. Recent studies have suggested that clinical and biologic markers of asthma severity predict variations in response to biologic therapies for the treatment of asthma.3, 4, 5

Our previous work from evaluations of omalizumab clinical trial data has indicated that higher levels of type 2 (T2) asthma biomarkers, including fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO), serum periostin, and blood eosinophil counts, predict a better response to omalizumab.3, 5 Similar findings have been noted for other biologic agents recently approved for severe asthma. Studies of an anti‐interleukin 5 (IL‐5) agent for severe asthma have demonstrated increased placebo‐corrected reductions in asthma exacerbations among patients with high blood eosinophil counts and a history of multiple asthma exacerbations in the preceding year; however, they did not show clear benefits in asthma subpopulations without such exacerbation history or with lower blood eosinophil counts.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Furthermore, specific thresholds of blood eosinophil counts have been incorporated as inclusion criteria for treatment with other biologic agents12, 13, 14 or inclusion criteria have been applied with enriching effects on the population being studied. For example, phase II and III trials of biologic therapies targeting the IL‐5 pathway enrolled patients with ≥2 or ≥3 exacerbations in the previous year, background use of long‐acting beta‐agonists (LABAs) ≥90%, baseline peripheral blood eosinophil count ≥300/μL, and percentage of predicted prebronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) <62.5.4, 6, 12, 15

Elevated blood eosinophil counts have been associated with more severe asthma and predict a higher risk of asthma exacerbations in patients already treated with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS).16, 17 Elevated blood eosinophils in patients with allergic asthma suggest an underlying T2 asthma phenotype, also known as T2 high asthma. T2 inflammation is driven by a specific profile of cytokines and mediators, including IgE, IL‐4, IL‐5, IL‐9, IL‐13, and IL‐33.18, 19, 20, 21 Although blood eosinophil count is an imperfect surrogate for airway eosinophils and may not be the optimal evaluation of T2 status, the relative ease of obtaining this measurement at the point of care has facilitated its use in clinical research. As newer biologic agents become available for asthma, it will be important to understand the extent to which these agents compare with existing therapies in the context of similar biomarkers and asthma severity.

We examined data from two pivotal trials22, 23 that constituted the basis for the regulatory approval of omalizumab in allergic asthma to identify whether baseline blood eosinophil counts predicted superior response to this therapy, using both specific cut points and a range of eosinophil levels. Because these pivotal trials included patients with either moderate or severe persistent allergic asthma, we examined the response to omalizumab in patients as a function of baseline asthma severity.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design

We examined pooled data from two pivotal, phase III, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled registration trials of omalizumab (N = 1071): 525 patients in study 122 and 546 patients in study 2.23 Each study was conducted in two phases after screening and randomization: a 16‐week ICS dose‐stable phase, followed by a 12‐week ICS dose‐reduction phase. Omalizumab was administered subcutaneously every 2 or 4 weeks at a dose calculated based on body weight and baseline serum IgE levels. Patients received omalizumab 150 mg or 300 mg every 4 weeks or 225 mg, 300 mg, or 375 mg every 2 weeks.22, 23 Detailed information regarding patient population and study design has been previously reported.22, 23

The primary end point for each study was the number of asthma exacerbations, defined as a requirement for systemic corticosteroids or a doubling of the ICS dose.22, 23 This analysis examined the annualized rate of asthma exacerbations during the 16‐week ICS dose‐stable phase of the studies, not during the 12‐week ICS dose‐reduction phase.

2.2. Study definitions

Since the pivotal trials were conducted, consensus recommendations have indicated that a requirement for systemic corticosteroids is the critical element in defining a severe asthma exacerbation.24 Thus, in defining the end point for the current analysis, we used the number of asthma exacerbations requiring ≥3 days of systemic corticosteroids during the 16‐week ICS dose‐stable phase of the studies as the exacerbation definition.

Type 2 (T2) inflammation status was defined based on baseline blood eosinophil levels (eosinophil count <300/μL [low] vs ≥300/μL [high]). We chose a threshold eosinophil count of 300/μL based on the precedent set by studies of omalizumab and other biologic agents.3, 4, 12, 14, 15 In addition, we examined exacerbation rate reductions associated with omalizumab by baseline blood eosinophil strata of ≥200/μL, ≥300/μL, and ≥400/μL, as described by Castro et al.12 Asthma severity was categorized separately as emergency asthma treatment or asthma hospitalization in the year before baseline, FEV1 at baseline (FEV1 <65% vs FEV1 ≥65% predicted), use of inhaled beclomethasone dipropionate (<600 μg/day vs ≥600 μg/day), and LABA use (yes vs no). The thresholds for FEV1 and beclomethasone were based on median cohort values.

2.3. Statistical analysis

CIs and P values for comparisons of exacerbation rates were calculated using unadjusted negative binomial models. Separate analyses using these models were conducted on subgroups to evaluate the potential effects of omalizumab on exacerbations in patients stratified by eosinophil counts and asthma severity.

We plotted annualized exacerbation rates in the omalizumab and placebo groups as a function of eosinophil counts based on a negative binomial regression model developed using the data from the omalizumab pivotal trials, and based on a similar previously published analysis by Pavord et al6 in the study of an anti–IL‐5 agent. Because eosinophils are log‐normally distributed, this variable was incorporated into the regression model after log‐transformation, with an interaction term between eosinophils and treatment group incorporated into modeling.

To examine how omalizumab efficacy might have varied in the hypothetical case that a more enriched population was enrolled into the original pivotal studies, a statistical simulation technique was employed. Negative binomial regression models were developed to predict asthma exacerbation rates in the omalizumab trials, with a subsequent imputation into the models of the actual observed estimates published from a recent anti–IL‐5 trial.6 Factors selected for the model were prespecified based on those available in both the omalizumab and mepolizumab (DREAM) studies: age, sex, race, body mass index, tobacco status, asthma duration, spirometry values, Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire score, LABA use, blood eosinophil count, and asthma hospitalization history. Average values from the anti–IL‐5 study were then incorporated into each model to estimate the asthma exacerbation reduction expected from omalizumab treatment within a population mirroring the anti–IL‐5 study. In addition, three factors were selected a priori to examine potential interactive effects by treatment response: (i) LABA use, (ii) blood eosinophils, and (iii) asthma hospitalizations in the year before baseline. Two regression models were developed from the omalizumab data, one taking into account only the main effects of each factor and the other including both the main effects and the interactive effect of treatment group with LABAs, blood eosinophils, and prior asthma hospitalization.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patient population

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were similar in the omalizumab and placebo groups (Table 1). The omalizumab and placebo groups had a mean (SD) age of 39.7 (13.8) and 39.0 (13.7) years, respectively, and the majority (55%) of patients were female. Asthma was long‐standing in these patients, with a mean (SD) duration of 20.5 (13.6) and 20.8 (14.0) years for patients in the omalizumab and placebo groups, respectively. A minority (~15%) of patients had previously been treated with a LABA and nearly 40% had received emergency asthma treatment in the year preceding enrollment.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics

| Characteristica | Pooled pivotal trials N = 1071 | |

|---|---|---|

| Omalizumab n = 542 | Placebo n = 529 | |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 39.7 (13.8) | 39.0 (13.7) |

| Female, % | 55 | 55 |

| Duration of asthma, years, mean (SD) | 20.5 (13.6) | 20.8 (14.0) |

| Prebronchodilator % predicted FEV1, mean (SD) | 65 (12.04) | 65 (11.13) |

| Blood eosinophil count, per μL, geometric mean (SE) | 253 (7.0) | 274 (7.7) |

| Serum IgE, IU/mL, geometric mean (SE) | 143 (5.29) | 144 (5.28) |

| Inhaled BDP dose, μg, mean (SD) | 670.4 (222.2) | 672.8 (238.3) |

| Treated with LABAs at baseline, % | 14.0 | 15.3 |

| Emergency asthma treatment in preceding year, % | 41.4 | 40.8 |

| Hospital admission for exacerbation in preceding year, % | 3.3 | 6.3 |

BDP, beclomethasone dipropionate; FEV1, forced expiratory volume at 1 s; IgE, immunoglobulin E; LABA, long‐acting beta‐agonist.

Percentages based on nonmissing data.

3.2. Effects of omalizumab vs placebo on asthma exacerbations overall

The rate of exacerbations requiring ≥3 days of systemic corticosteroid treatment was 0.066 in patients receiving omalizumab and 0.147 in patients receiving placebo, representing a relative rate reduction in patients receiving omalizumab of 55% (95% CI, 32%‐70%; P = .002).

3.3. Effects of omalizumab vs placebo on asthma exacerbations based on blood eosinophils and asthma severity

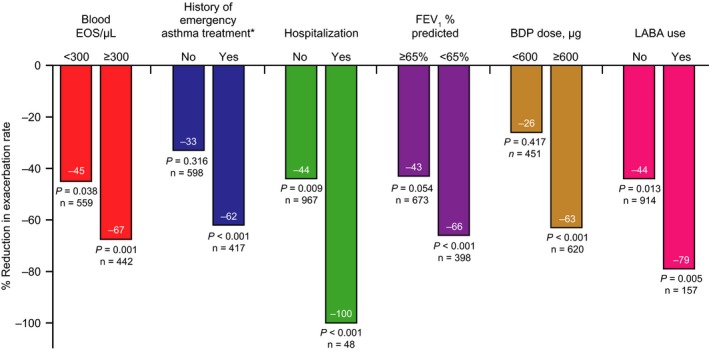

Exacerbation reduction was more pronounced with omalizumab vs placebo in patients with higher eosinophil counts (eosinophil count ≥300/μL) and with more severe asthma (history of emergency asthma treatment, history of hospitalization, FEV1 <65% predicted, requirement for beclomethasone ≥600 μg/day, requirement for LABA use) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Percentage reduction in exacerbation rate with omalizumab vs placebo by blood EOS level and clinical indices of asthma severity. P values represent comparison of exacerbation rate reductions for omalizumab vs placebo within EOS and severity subgroups using unadjusted negative binomial models. BDP, beclomethasone dipropionate; EOS, eosinophil; FEV 1, forced expiratory volume at 1 second; LABA, long‐acting beta‐agonist. *Defined as history of overnight hospital admission for asthma, emergency department visit for asthma, or urgent doctor's office visit for asthma

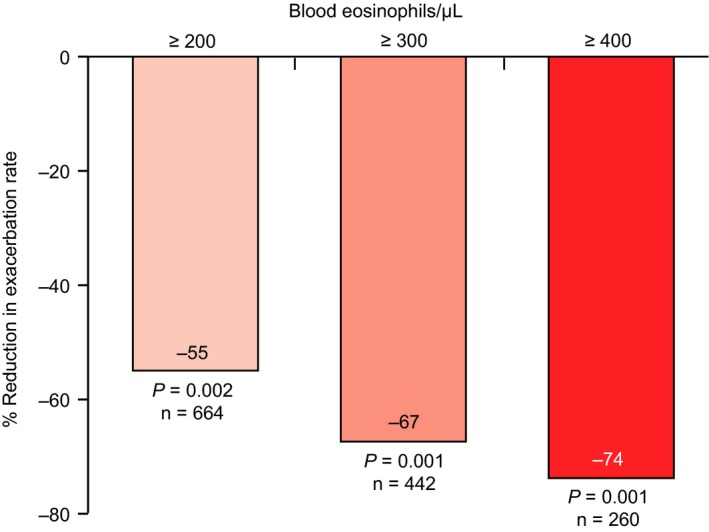

Mean exacerbation rate reductions associated with omalizumab by baseline blood eosinophil strata were as follows: ≥200/μL, 55% (95% CI, 25%‐73%; P = .002); ≥300/μL, 67% (95% CI, 36%‐84%; P = .001); and ≥400/μL, 74% (95% CI, 40%‐88%; P = .001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Relative percentage change in exacerbation rate by blood eosinophil levels

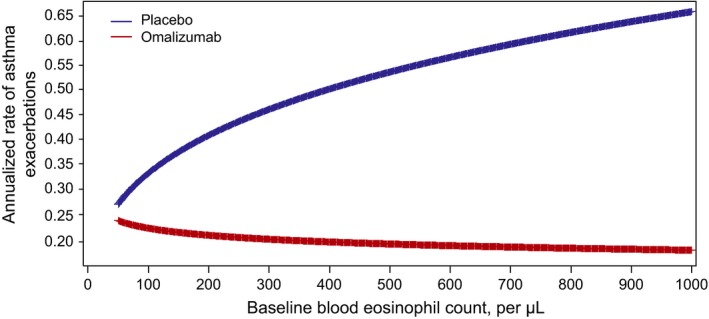

Asthma exacerbation rates with placebo and omalizumab as a function of eosinophil counts were graphed based on a negative binomial regression model (Figure 3). The model shows that the efficacy benefit of omalizumab increases with increasing baseline eosinophil count, suggesting that response to omalizumab is observed across a wide range of eosinophil levels but is better with higher eosinophil levels.

Figure 3.

Asthma exacerbation rates as a function of eosinophil counts based on a regression model from pivotal trial data

3.4. Use of statistical simulations to attempt to determine omalizumab efficacy in a more enriched population of patients

The results of these simulations revealed an increase to 57% from the original unadjusted exacerbation rate reduction of 53%, when adjusting only for main effects, and up to 86% when also incorporating interactions into the model (Table 2). This suggests that if the original omalizumab trials had enrolled a more enriched population, similar to that enrolled in the more recent anti–IL‐5 trial,6 the efficacy would have been greater than was observed.

Table 2.

Baseline clinical characteristics for factors included as interactions in modeling and model results of estimated exacerbation reductions with omalizumab

| Characteristica | Pooled pivotal trials N = 1071 | DREAM study N = 616 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omalizumab n = 542 | Placebo n = 529 | Mepolizumab n = 460 | Placebo n = 156 | |

| Treated with LABAs at baseline, % | 14 | 15 | 95 | 97 |

| Blood eosinophil count, per μL, geometric mean | 253 | 274 | 243 | 280 |

| Hospital admission for exacerbation in preceding year, % | 3.3 | 6.3 | 24 | 26 |

| Model results of estimated exacerbation rate reductions with omalizumab | Omalizumab | Placebo | % Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exacerbation rate, base case (without adjustment) | 0.28 | 0.60 | 53 |

| Exacerbation rate, adjusting for main effect differencesa , b | 0.18 | 0.42 | 57 |

| Exacerbation rate, adjusting for main effect differences and including interactions for LABA use, blood eosinophil count, and prior asthma hospitalizationa , b | 0.08 | 0.57 | 86 |

LABA, long‐acting beta‐agonist.

Between the pooled pivotal trials and DREAM cohorts.

Exacerbation rate over the 16‐wk inhaled corticosteroid‐stable phase, adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, tobacco use status, asthma duration, spirometry value, Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire score, LABA use, blood eosinophil count, and asthma hospitalization history.

4. DISCUSSION

In the current analysis of data from the two pivotal registration trials in patients with allergic asthma, patients treated with omalizumab demonstrated fewer exacerbations requiring systemic corticosteroids compared with patients treated with placebo. This reduction was more pronounced in patients demonstrating increased asthma severity, as measured by specific clinical markers (requiring LABA use, requiring higher ICS dosage, lower FEV1, or a history of asthma hospitalization or emergency department visits), and in those with high baseline blood eosinophil counts. Findings from these post hoc analyses are consistent with other analyses demonstrating that increased baseline levels of eosinophils and other T2 biomarkers, which indicate the presence of higher disease activity, are associated with a better response to omalizumab.3, 5, 25 Indeed, the efficacy benefit of omalizumab was observed across a wide range of eosinophil levels, rather than specific cut points. Additionally, simulation analyses indicated that the efficacy of omalizumab would have been greater had the original omalizumab trials enrolled a more enriched population, similar to that enrolled in the more recent anti–IL‐5 trials.6, 15, 26

Our findings support the importance of asthma severity in predicting response to omalizumab. Clinical signs of asthma severity and increased levels of biomarkers are, collectively, signs of residual disease activity despite intensive steroid therapy. Based on the current evidence available, various clinical criteria and biomarkers can be useful to predict a greater treatment effect with omalizumab as well as with other monoclonal antibodies. A previous publication demonstrated that higher baseline levels of T2 biomarkers (specifically blood eosinophils, serum periostin, or FeNO) predict a greater likelihood of patients having an asthma exacerbation within the placebo arm of studies.5 This suggests that increased levels of T2 biomarkers are themselves prognostic markers and reflect greater asthma severity. Thus, it remains unclear the extent to which clinical markers of asthma severity alone, relative to biomarkers that reflect T2 status, may be driving the greater response to omalizumab.

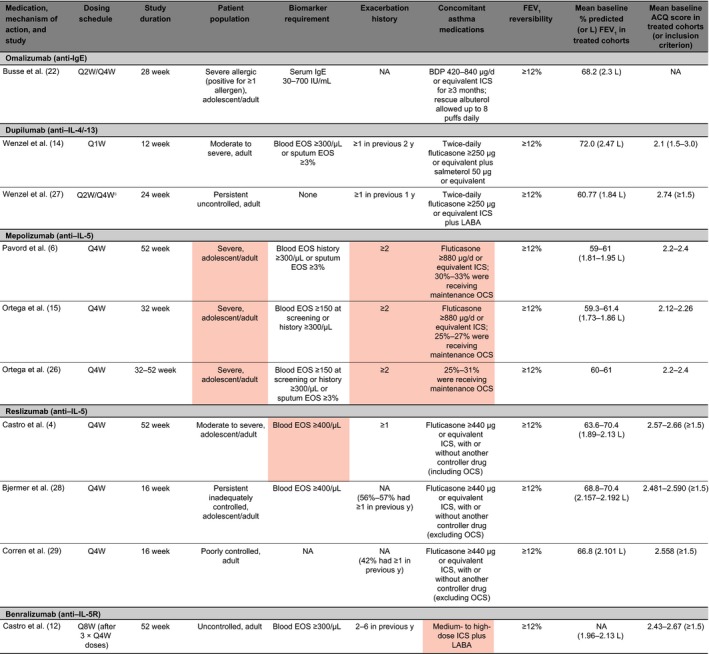

Our graph of exacerbation rates as a function of eosinophil counts using a negative binomial regression model (Figure 3) showed a pattern similar to that seen in the DREAM study with mepolizumab.6 Our analysis not only confirms findings from our previous study demonstrating that blood eosinophil counts predict a significant response to omalizumab in patients with severe allergic asthma,5 but also expands those findings to include a wider range of eosinophil counts, rather than applying specific cut points. Other studies of biologic therapies have examined efficacy based on eosinophil cut points; however, the studies varied considerably in the patient populations examined, study durations, and dosing schedules (Figure 4).4, 6, 12, 14, 15, 22, 26, 27, 28, 29 Dupilumab14 was dosed on a weekly basis over a 12‐week period in patients with persistent asthma and blood eosinophil counts ≥300/μL or sputum eosinophils ≥3%. Patients in this study also were required to have ≥1 asthma exacerbation in the year before screening. Reslizumab4, 13, 28, 29 was dosed every 4 weeks in patients with blood eosinophil counts ≥400/μL and a history of asthma exacerbations. Inadequately controlled asthma, as measured by the Asthma Control Questionnaire, also was a requirement for study entry for both dupilumab and reslizumab. The mepolizumab DREAM6 and MENSA15 studies included patient populations enriched for severe asthma, high blood eosinophil counts at baseline (≥150/μL) or within a year of enrollment (≥300/μL), and ≥2 asthma exacerbations in the year before screening. Response to mepolizumab increased with baseline blood eosinophil count6, 15 and with the number of asthma exacerbations in the preceding year.6 In another recent study, 52 weeks of treatment with the anti–IL‐5 receptor monoclonal antibody benralizumab was examined in patients with blood eosinophil counts ≥300/μL and ≥2 exacerbations in the year before screening.12

Figure 4.

Comparison of key asthma biologic trials in adults with or without adolescents. Red shading indicates characteristics of more severe asthma. ACQ, Asthma Control Questionnaire; BDP, beclomethasone dipropionate; EOS, eosinophil count; FEV 1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; IgE, immunoglobulin E; IL, interleukin; LABA, long‐acting beta‐agonist; NA, not applicable/available; OCS, oral corticosteroid; Q1W, every week; Q2W, every 2 weeks; Q4W, every 4 weeks; Q8W, every 8 weeks; y, years

Of note, a substantial proportion of patients in the biologic trials summarized above were recruited from countries other than the United States. The prevalence among patients with asthma in the United States of unstable disease, defined by high T2 biomarker counts and multiple exacerbations in a 12‐month period despite treatment with ICS and LABA, is uncertain.

The treatment effects of the various biologic agents in patient populations not enriched by these clinical markers of severity have yet to be elucidated. However, a recent 24‐week trial of dupilumab in 776 patients who were included without enrichment for eosinophil levels (but were required to have ≥1 systemic corticosteroid burst therapy or ≥1 hospital admission or emergency department/urgent care visit that required systemic steroids in the previous year) showed that the subgroup of patients with baseline eosinophil count <300/μL who received dupilumab 200 mg or 300 mg every 2 weeks had exacerbation risk reductions vs placebo of 67.6% (P = .0081) and 59.9% (P = .0152), respectively.27

Given the variability in study design, patient inclusion criteria, study duration, dosing schedules, and biomarker requirements across the various biologic therapies for asthma, it is difficult to directly compare their efficacy. However, the findings of this post hoc study demonstrating an improved and comparable response to omalizumab in patients with a history of asthma hospitalization or emergency department visits, and in those with high baseline blood eosinophil counts, are particularly noteworthy given that the trials for omalizumab were not enriched for these factors, unlike the studies of other biologic therapies; enrichment inherently allows for greater efficacy because patients with more severe asthma and more frequent exacerbations have more room for improvement. This finding also is important within the concept of an eosinophilic asthma phenotype, because omalizumab is not thought to work directly through inhibition of eosinophils. However, omalizumab has been reported to reduce airway eosinophils30, 31, 32, 33, 34 as well as peripheral blood eosinophils.35, 36 The efficacy of omalizumab also was demonstrated regardless of LABA use.

This analysis has limitations that should be considered. First, this is a post hoc analysis using pooled data from two separate pivotal clinical trials and, thus, consideration of these results should be in the context of other evidence related to omalizumab and predictors of response. In addition, other markers of T2‐driven disease, such as FeNO and periostin, were not well known at the time of the omalizumab pivotal trials and data were not collected. Further, because of evolving changes in practice standards, the omalizumab allergic asthma pivotal trials had a substantially smaller proportion of patients receiving a LABA than is typically seen in current practice; however, these patients were being treated with ICS recommended as primary controller therapy by all guidelines at the time. In addition, the observation period of this study was relatively short (16 weeks), with consequently low numbers of exacerbations. Lastly, the number of historical asthma exacerbations was not available in the pivotal trial data set. However, prior asthma hospitalization is a similar measure of historical disease severity. Despite the post hoc nature of these analyses, the consistency of the results from these two clinical trials is noteworthy.

In summary, our findings suggest that patients with clinical markers of greater asthma severity or high baseline blood eosinophil count have a more pronounced reduction of asthma exacerbations requiring systemic steroid therapy when treated with omalizumab than patients with asthma who do not have these markers. However, in contrast to other biologic agents (eg, anti–IL‐5 therapies), omalizumab does significantly reduce exacerbation rates regardless of baseline eosinophil levels. Our results reaffirm that patients with prior exacerbations and higher blood eosinophil levels are at greater risk for more exacerbations.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

T. Casale's university employer has received grants and consulting fees from Genentech, Inc., and Novartis. B.E. Chipps has received honoraria for serving as a consultant and speaker from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Genentech, Inc., Meda, Merck, and Novartis. K. Rosén, B. Trzaskoma, and T.A. Omachi are employees of Genentech, Inc., and receive stock options from Roche. T. Haselkorn serves as a consultant to Genentech, Inc., and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. S. Greenberg was an employee of Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation at the time of this work and held restricted stock units from Novartis. N.A. Hanania has received honoraria for serving as a consultant or on advisory boards, and his institution received research grant support from Genentech, Inc., and Novartis.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in the conception and design of the study, in the analysis and interpretation of the data, in the preparation or critical revision of the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Medical writing support for this manuscript was provided by Margit Rezabek and Linda Wagner of Excel Scientific Solutions and funded by Genentech, Inc., and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Casale TB, Chipps BE, Rosén K, et al. Response to omalizumab using patient enrichment criteria from trials of novel biologics in asthma. Allergy. 2018;73:490–497. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.13302

Funding information

The pivotal studies were designed and funded by Genentech, Inc., South San Francisco, CA, USA, and Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland. The current analysis also was funded by Genentech, Inc., and Novartis Pharma AG

Edited by: Marek Sanak

REFERENCES

- 1. Xolair [package insert]. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech USA, Inc.; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. European Medicines Agency . Xolair summary of product characteristics. 2016. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000606/WC500057298.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2016.

- 3. Busse W, Spector S, Rosén K, Wang Y, Alpan O. High eosinophil count: a potential biomarker for assessing successful omalizumab treatment effects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:485‐486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Castro M, Zangrilli J, Wechsler ME, et al. Reslizumab for inadequately controlled asthma with elevated blood eosinophil counts: results from two multicentre, parallel, double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:355‐366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hanania NA, Wenzel S, Rosén K, et al. Exploring the effects of omalizumab in allergic asthma: an analysis of biomarkers in the EXTRA study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:804‐811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pavord ID, Korn S, Howarth P, et al. Mepolizumab for severe eosinophilic asthma (DREAM): a multicentre, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:651‐659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Flood‐Page P, Swenson C, Faiferman I, et al. International Mepolizumab Study Group. A study to evaluate safety and efficacy of mepolizumab in patients with moderate persistent asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:1062‐1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nair P, Pizzichini MM, Kjarsgaard M, et al. Mepolizumab for prednisone‐dependent asthma with sputum eosinophilia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:985‐993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kips JC, O'Connor BJ, Langley SJ, et al. Effect of SCH55700, a humanized anti‐human interleukin‐5 antibody, in severe persistent asthma: a pilot study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1655‐1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leckie MJ, ten Brinke A, Khan J, et al. Effects of an interleukin‐5 blocking monoclonal antibody on eosinophils, airway hyper‐responsiveness, and the late asthmatic response. Lancet. 2000;356:2144‐2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Haldar P, Brightling CE, Hargadon B, et al. Mepolizumab and exacerbations of refractory eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:973‐984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Castro M, Wenzel SE, Bleecker ER, et al. Benralizumab, an anti‐interleukin 5 receptor α monoclonal antibody, versus placebo for uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma: a phase 2b randomised dose‐ranging study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:879‐890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Castro M, Mathur S, Hargreave F, et al. Res‐5‐0010 Study Group. Reslizumab for poorly controlled, eosinophilic asthma: a randomized, placebo‐controlled study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:1125‐1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wenzel S, Ford L, Pearlman D, et al. Dupilumab in persistent asthma with elevated eosinophil levels. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2455‐2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ortega HG, Liu MC, Pavord ID, et al. for the MENSA Investigators. Mepolizumab treatment in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1198‐1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zeiger RS, Schatz M, Li Q, et al. High blood eosinophil count is a risk factor for future asthma exacerbations in adult persistent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2:741‐750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zeiger RS, Schatz M, Li Q, et al. The association of blood eosinophil counts to future asthma exacerbations in children with persistent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3:283‐287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Deo SS, Mistry KJ, Kakade AM, Niphadkar PV. Role played by Th2 type cytokines in IgE mediated allergy and asthma. Lung India. 2010;27:66‐71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jackson DJ, Makrinioti H, Rana BM, et al. IL‐33–dependent type 2 inflammation during rhinovirus‐induced asthma exacerbations in vivo . Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:1373‐1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Licona‐Limón P, Kim LK, Palm NW, Flavell RA. TH2, allergy and group 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:536‐542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Spellberg B, Edwards JE Jr. Type 1/type 2 immunity in infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:76‐102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Busse W, Corren J, Lanier BQ, et al. Omalizumab, anti‐IgE recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of severe allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:184‐190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Soler M, Matz J, Townley R, et al. The anti‐IgE antibody omalizumab reduces exacerbations and steroid requirement in allergic asthmatics. Eur Respir J. 2001;18:254‐261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reddel HK, Taylor DR, Bateman ED, et al. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Task Force on Asthma Control and Exacerbations. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: asthma control and exacerbations: standardizing endpoints for clinical asthma trials and clinical practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:59‐99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bousquet J, Wenzel S, Holgate S, Lumry W, Freeman P, Fox H. Predicting response to omalizumab, an anti‐IgE antibody, in patients with allergic asthma. Chest. 2004;125:1378‐1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ortega HG, Yancey SW, Mayer B, et al. Severe eosinophilic asthma treated with mepolizumab stratified by baseline eosinophil thresholds: a secondary analysis of the DREAM and MENSA studies. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4:549‐556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wenzel S, Castro M, Corren J, et al. Dupilumab efficacy and safety in adults with uncontrolled persistent asthma despite use of medium‐to‐high‐dose inhaled corticosteroids plus a long‐acting β2 agonist: a randomised double‐blind placebo‐controlled pivotal phase 2b dose‐ranging trial. Lancet. 2016;388:31‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bjermer L, Lemiere C, Maspero J, Weiss S, Zangrilli J, Germinaro M. Reslizumab for inadequately controlled asthma with elevated blood eosinophil levels: a randomized phase 3 study. Chest. 2016;150:789‐798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Corren J, Weinstein S, Janka L, Zangrilli J, Garin M. Phase 3 study of reslizumab in patients with poorly controlled asthma: effects across a broad range of eosinophil counts. Chest. 2016;150:799‐810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Djukanović R, Wilson SJ, Kraft M, et al. Effects of treatment with anti‐immunoglobulin E antibody omalizumab on airway inflammation in allergic asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:583‐593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Riccio AM, Dal Negro RW, Micheletto C, et al. Omalizumab modulates bronchial reticular basement membrane thickness and eosinophil infiltration in severe persistent allergic asthma patients. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2012;25:475‐484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Takaku Y, Soma T, Nishihara F, et al. Omalizumab attenuates airway inflammation and interleukin‐5 production by mononuclear cells in patients with severe allergic asthma. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2013;161(suppl 2):107‐117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. van Rensen EL, Evertse CE, van Schadewijk WA, et al. Eosinophils in bronchial mucosa of asthmatics after allergen challenge: effect of anti‐IgE treatment. Allergy. 2009;64:72‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fahy JV, Fleming HE, Wong HH, et al. The effect of an anti‐IgE monoclonal antibody on the early‐ and late‐phase responses to allergen inhalation in asthmatic subjects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:1828‐1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Massanari M, Holgate ST, Busse WW, Jimenez P, Kianifard F, Zeldin R. Effect of omalizumab on peripheral blood eosinophilia in allergic asthma. Respir Med. 2010;104:188‐196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Noga O, Hanf G, Brachmann I, et al. Effect of omalizumab treatment on peripheral eosinophil and T‐lymphocyte function in patients with allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1493‐1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]