Abstract

Aims

To assess the safety and efficacy of monotherapy with once‐weekly subcutaneous (s.c.) semaglutide vs sitagliptin in Japanese people with type 2 diabetes (T2D).

Methods

In this phase IIIa randomized, open‐label, parallel‐group, active‐controlled, multicentre trial, Japanese adults with T2D treated with diet and exercise only or oral antidiabetic drug monotherapy (washed out during the run‐in period) received once‐weekly s.c. semaglutide (0.5 or 1.0 mg) or once‐daily oral sitagliptin 100 mg. The primary endpoint was number of treatment‐emergent adverse events (TEAEs) after 30 weeks.

Results

Overall, 308 participants were randomized and exposed to treatment, with similar baseline characteristics across the groups. In total, 2.9% of participants in both the semaglutide 0.5 mg and the sitagliptin group prematurely discontinued treatment, compared with 14.7% in the semaglutide 1.0 mg group. The majority of discontinuations in the semaglutide 0.5 and 1.0 mg groups were attributable to adverse events (AEs). More TEAEs were reported in semaglutide‐ vs sitagliptin‐treated participants (74.8%, 71.6% and 66.0% in the semaglutide 0.5 mg, semaglutide 1.0 mg and sitagliptin groups, respectively). AEs were mainly mild to moderate. Gastrointestinal AEs, most frequently reported with semaglutide, diminished in frequency over time. The mean glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c [baseline 8.1%]) decreased by 1.9% and 2.2% with semaglutide 0.5 and 1.0 mg, respectively, vs 0.7% with sitagliptin (estimated treatment difference [ETD] vs sitagliptin −1.13%, 95% confidence interval [CI] −1.32; −0.94, and −1.44%, 95% CI −1.63; −1.24; both P < .0001). Body weight (baseline 69.3 kg) was reduced by 2.2 and 3.9 kg with semaglutide 0.5 and 1.0 mg, respectively (ETD −2.22 kg, 95% CI −3.02; −1.42 and −3.88 kg, 95% CI −4.70; −3.07; both P < .0001).

Conclusions

In Japanese people with T2D, more TEAEs were reported with semaglutide than with sitagliptin; however, the semaglutide safety profile was similar to that of other glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists. Semaglutide significantly reduced HbA1c and body weight compared with sitagliptin.

Keywords: GLP‐1, sitagliptin, type 2 diabetes

1. INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes (T2D) and prediabetes increased significantly from the 1980s to the 2000s in the Japanese population, with increasing obesity and declining physical activity.1

Achieving glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) targets is a challenge for many patients with T2D.2 Avoidance of weight gain and hypoglycaemia are important considerations in selecting appropriate treatment and individualizing treatment goals.3, 4 Unlike most other T2D therapies, glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1) receptor agonists (RAs) can achieve glycaemic control and reduce body weight, with a low risk of hypoglycaemia.5

Semaglutide is a GLP‐1 analogue in development for the treatment of T2D, with a 94% homology to native GLP‐1.6 A half‐life of ~1 week makes it appropriate for once‐weekly administration.6, 7

Sitagliptin, a once‐daily dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 (DPP‐4) inhibitor, is a widely used oral antidiabetic drug (OAD), and the most commonly used DPP‐4 inhibitor in Japan.8 DPP‐4 inhibitors achieve glycaemic control by inhibiting DPP‐4‐dependent inactivation of both GLP‐1 and gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP), thereby enhancing GLP‐1 and GIP receptor signalling, and thus are distinct from GLP‐1 RAs, which stably activate GLP‐1 receptor signalling.9

Semaglutide has been evaluated in the “Semaglutide Unabated Sustainability in Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes” (SUSTAIN) programme, consisting of six phase III global clinical trials that evaluated the efficacy and safety (including cardiovascular outcomes) of semaglutide vs a range of comparators, including sitagliptin.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 Two additional phase III clinical trials in the SUSTAIN programme investigated the effect of semaglutide in Japanese populations.16, 17

In the present trial we evaluated the safety and efficacy of 30 weeks of treatment with once‐weekly semaglutide (0.5 and 1.0 mg) vs once‐daily sitagliptin (100 mg), both as monotherapy, in Japanese adults with T2D who were previously stable on diet/exercise or OAD monotherapy.17

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Trial design

This was a phase III randomized (1:1:1), open‐label, parallel‐group, active‐controlled, single‐country (Japan), multicentre trial (NCT02254291; Figure S1). This trial was conducted to meet the “Guideline for Clinical Evaluation of Oral Hypoglycaemic Agents” issued by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare,18 which advises that new drugs are assessed as monotherapy to investigate their isolated effects. A specific comparator is not stipulated in the guideline; however, sitagliptin was chosen as an active comparator because it is widely available in Japan,8 and has a well‐known efficacy and safety profile. The trial was conducted in compliance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines19 and the Declaration of Helsinki.20 Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.2. Trial population

Japanese men and women were eligible for inclusion if they were aged ≥20 years, diagnosed with T2D, and treated with either diet and exercise therapy in addition to OAD monotherapy if their HbA1c levels were 6.5% to 9.5% (48–80 mmol/mol; hereafter called OAD monotherapy), or treated with diet and exercise therapy only if their HbA1c levels were 7.0% to 10.5% (53–91 mmol/mol) for at least 30 days before screening.

Key exclusion criteria were: treatment with glucose‐lowering agents (except for pre‐trial OAD in participants treated with OAD monotherapy) in the 60 days before screening (except for short‐term use of insulin in connection with intercurrent illness of ≤7 days); history of chronic or idiopathic acute pancreatitis; screening calcitonin value ≥50 ng/L; personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2; impaired renal function (estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 per modification of diet in renal disease formula [4‐variable version]); acute coronary or cerebrovascular event within 90 days before randomization; or heart failure, New York Heart Association class IV. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table S1.

2.3. Randomization and masking

Participants were randomly assigned using an interactive voice/web response system in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive once‐weekly subcutaneous (s.c.) semaglutide (0.5 or 1.0 mg) or once‐daily oral sitagliptin 100 mg. Randomization was stratified according to pre‐trial treatment at screening (diet and exercise therapy or OAD monotherapy).

2.4. Drug administration

After an 8‐week washout (OAD monotherapy group) or 2‐week screening period (diet and exercise only group), participants received s.c. semaglutide 0.5 or 1.0 mg once weekly or sitagliptin 100 mg once daily for 30 weeks, followed by a 5‐week follow‐up period (Figure S1). Participants in the semaglutide arms followed a fixed dose‐escalation regimen of semaglutide 0.5 mg (maintenance dose reached after 4 weeks of 0.25 mg semaglutide once weekly) or semaglutide 1.0 mg (maintenance dose reached after 4 weeks of 0.25 mg semaglutide, followed by 4 weeks of 0.5 mg semaglutide).

In case of a safety concern or unacceptable intolerability, the trial product could be discontinued at the investigator’s discretion and was not to be reinitiated. Participants discontinuing trial product prematurely were asked to continue with the scheduled site contact (if necessary, in order to retain the participant in the trial, site visits were replaced by phone contacts after discontinuation) and, as a minimum, were asked to attend the visits for end of treatment and follow‐up at the time of the scheduled completion of the trial.

2.5. Trial endpoints and assessments

The primary endpoint was the number of treatment‐emergent adverse events (TEAEs) during 30 weeks of treatment.

Supportive secondary efficacy endpoints included change from baseline to week 30 in: HbA1c; fasting plasma glucose (FPG); self‐measured plasma glucose (SMPG [measurements performed with capillary blood were automatically calibrated to plasma‐equivalent glucose values, shown on the display of the blood glucose (BG) meter and documented by the trial participant]; mean 7‐point profile and mean postprandial increment, over all meals); body weight; body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference; fasting blood lipid levels (free fatty acids [FFAs], total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, VLDL cholesterol and triglycerides); and systolic and diastolic blood pressure (BP). Other efficacy endpoints included the proportion of participants reaching HbA1c targets of ≤6.5% (American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists [AACE]),21 <7.0% (American Diabetes Association [ADA] and Japan Diabetes Society [JDS])22, 23 and <7.0% without severe or BG‐confirmed symptomatic hypoglycaemia (defined as an episode that was severe according to ADA classification22 or BG‐confirmed by plasma glucose <3.1 mmol/L, with symptoms consistent with hypoglycaemia) and no weight gain, and proportion of participants achieving weight loss of ≥5% or ≥10% at week 30.

Supportive secondary safety endpoints included: the number of treatment‐emergent severe or BG‐confirmed symptomatic hypoglycaemic episodes during 30 weeks of treatment; change from baseline to week 30 in laboratory and physical examination variables; and occurrence of anti‐semaglutide antibodies. An external Event Adjudication Committee (EAC) validated selected adverse events (AEs), according to predefined diagnostic criteria, in an independent, blinded manner (Table S2). Events were adjudicated according to Food and Drug Administration guidance and requirements.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Trial sample size was determined based on the “Guideline for Clinical Evaluation of Oral Hypoglycaemic Agents.”18 With the planned number of randomized participants of 306, a total of 81 participants randomized to each group were expected to complete treatment, assuming a treatment discontinuation rate of 20%. Together with the other trials in the SUSTAIN programme, ≥300 Japanese participants were expected to complete ≥6 months of treatment with semaglutide monotherapy.

Randomized participants receiving at least 1 dose of trial product comprised the full analysis set and the safety analysis set.

A TEAE was defined as an event with onset from first exposure to the follow‐up visit scheduled 5 weeks (+1 week visit window) after the last trial product dose.

Main efficacy evaluations were based on assessments collected in the period where participants were treated with trial product, without rescue medication (“on‐treatment without rescue medication” period). Supportive analyses of efficacy and safety were based on assessments collected in the period where participants, after randomization, were considered trial participants and where data were to be collected systematically (“in‐trial” period). Continuous efficacy endpoints assessed over time were analysed using a mixed model for repeated measurements (MMRM) with treatment and pre‐trial treatment at screening as fixed factors and baseline value as a covariate, all nested within visits. With the exception of HbA1c, body weight, FPG, SMPG, BMI, waist circumference and BP, values were log‐transformed before analysis. Efficacy continuous endpoints assessed at baseline and week 30 were analysed using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model. For the HbA1c target endpoints (<7% and ≤6.5%) and weight loss response endpoints (≥5% and ≥10%), missing data at week 30 were imputed from the MMRM, used for the corresponding continuous endpoint, and subsequently classified. Treatment comparison was based on a logistic regression model including the same fixed factors and associated baseline value(s) as covariate, except for the weight‐loss response of ≥10%, which was compared using a Fisher’s exact test, as no participants achieved this response in the sitagliptin group.

The sensitivity of the main results of HbA1c and body weight was assessed using complete case analyses (MMRM‐based), ANCOVA using the last observation carried forward (LOCF) imputation, and comparator‐based multiple imputation.

Data collected throughout the trial, regardless of whether participants discontinued treatment prematurely or initiated rescue medication, were also analysed (“in‐trial” analysis; MMRM based); thus, the amount of missing data was expected to be small.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participant disposition and baseline characteristics

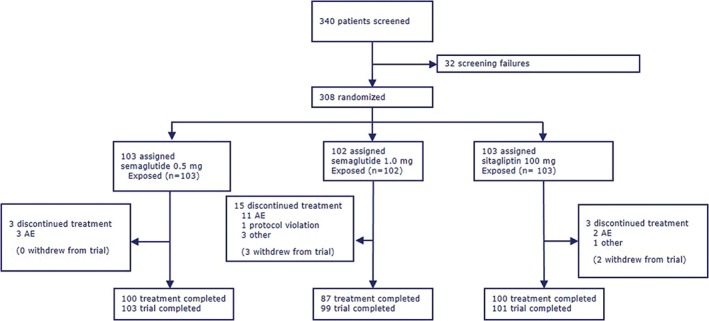

In total, 308 adults with T2D were randomized to receive 1 of the 2 semaglutide maintenance doses or sitagliptin, all of whom were exposed to trial product (Figure 1). A higher proportion of participants discontinued treatment prematurely in the semaglutide 1.0 mg group (14.7%) compared with the semaglutide 0.5 mg and sitagliptin groups (each 2.9%). All semaglutide 0.5 mg‐treated participants completed the trial, whereas 3 participants in the semaglutide 1.0 mg group and 2 in the sitagliptin group withdrew prematurely. Rescue medication was provided to 1 participant in the semaglutide 0.5 mg group and 5 participants in the sitagliptin group.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through the trial. Numbers in brackets within treatment discontinuation category denote subjects who also withdrew from trial, as those who discontinued treatment had the option to continue follow‐up. Trial completers were participants who were exposed, did not withdraw from trial and who attended a follow‐up

Baseline characteristics were generally well balanced between the three groups (Table 1). The majority (76.3%) of participants were men, mean HbA1c was 8.1%, mean diabetes duration was 8.0 years, and the proportion of participants randomized while on pre‐trial OAD treatment was 29.9%. Mean body weight was 69.3 kg, although participants in the semaglutide 1.0 mg group were 3.0 kg heavier than in the semaglutide 0.5 mg group (70.8 vs 67.8 kg).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of trial populations

| Semaglutide 0.5 mg | Semaglutide 1.0 mg | Sitagliptin 100 mg | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. | |

| Age, years | 58.8 | 10.4 | 58.1 | 11.6 | 57.9 | 10.1 | 58.3 | 10.7 |

| Male/female, % | 76.7/23.3 | ‐ | 73.5/26.5 | ‐ | 78.6/21.4 | ‐ | 76.3/23.7 | ‐ |

| HbA1c, % | 8.2 | 1.0 | 8.0 | 0.9 | 8.2 | 0.9 | 8.1 | 0.9 |

| FPG, mmol/L | 9.2 | 2.1 | 9.2 | 1.8 | 9.5 | 2.0 | 9.3 | 2.0 |

| Diabetes duration, years | 8.0 | 5.2 | 7.8 | 6.9 | 8.1 | 6.7 | 8.0 | 6.3 |

| Body weight, kg | 67.8 | 11.7 | 70.8 | 16.4 | 69.4 | 12.9 | 69.3 | 13.8 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.1 | 3.8 | 26.1 | 5.2 | 25.1 | 3.6 | 25.4 | 4.3 |

| Previously treated with: | ||||||||

| Diet and exercise therapy, % | 69.9 | ‐ | 70.6 | ‐ | 69.9 | ‐ | 70.1 | ‐ |

| OAD therapy, % | 30.1 | ‐ | 29.4 | ‐ | 30.1 | ‐ | 29.9 | ‐ |

| Biguanides | 11.7 | ‐ | 12.7 | ‐ | 11.7 | ‐ | 12.0 | ‐ |

| SU | 4.9 | ‐ | 2.0 | ‐ | 4.9 | ‐ | 3.9 | ‐ |

| α‐GI | 1.9 | ‐ | 2.9 | ‐ | 1.9 | ‐ | 2.3 | ‐ |

| TZDs | 1.9 | ‐ | 2.0 | ‐ | 2.9 | ‐ | 2.3 | ‐ |

| DPP‐4 inhibitors | 7.8 | ‐ | 6.9 | ‐ | 5.8 | ‐ | 6.8 | ‐ |

| Other BG‐lowering drugsa | 1.9 | ‐ | 2.9 | ‐ | 2.9 | ‐ | 2.6 | ‐ |

Abbreviations: α‐GI, α‐glucosidase inhibitor; BG, blood glucose; BMI, body mass index; DPP‐4, dipeptidyl peptidase‐4; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; OAD, oral antidiabetic drug; s.d., standard deviation; SU, sulphonylurea; TZD, thiazolidinedione.

Excluding insulin. Summary is based on the full analysis set.

3.2. Primary endpoint

Overall, the proportion of participants reporting TEAEs during the trial (primary endpoint) was higher with semaglutide (0.5 mg: 74.8%; 1.0 mg: 71.6%) than with sitagliptin (66.0%) (Table 2). AEs were mainly mild or moderate in severity (Table 2). The proportion of participants discontinuing treatment because of AEs was relatively low for semaglutide 0.5 mg and sitagliptin (2.9% and 1.9%, respectively), but higher for semaglutide 1.0 mg (10.8%) (Figure S2). Serious AEs (SAEs) were reported by 5.8%, 2.0% and 1.9% of participants treated with semaglutide 0.5 mg, 1.0 mg and sitagliptin, respectively. Events were distributed among multiple system organ classes, with no clustering (Table S3). No deaths were reported in the trial (Table 2).

Table 2.

Treatment‐emergent adverse events overview

| Semaglutide 0.5 mg | Semaglutide 1.0 mg | Sitagliptin 100 mg | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | E | R | N | (%) | E | R | N | (%) | E | R | |

| Number of participants | 103 | 102 | 103 | |||||||||

| AEs: total | 77 | (74.8) | 228 | 331.8 | 73 | (71.6) | 197 | 312.6 | 68 | (66.0) | 186 | 267.4 |

| Fatal | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Serious | 6 | (5.8) | 7 | 10.2 | 2 | (2.0) | 2 | 3.2 | 2 | (1.9) | 3 | 4.3 |

| Severity of AEs | ||||||||||||

| Severe | 2 | (1.9) | 2 | 2.9 | 1 | (1.0) | 1 | 1.6 | 2 | (1.9) | 5 | 7.2 |

| Moderate | 13 | (12.6) | 23 | 33.5 | 9 | (8.8) | 12 | 19.0 | 10 | (9.7) | 10 | 14.4 |

| Mild | 73 | (70.9) | 203 | 295.4 | 68 | (66.7) | 184 | 292.0 | 67 | (65.0) | 171 | 245.8 |

| Leading to premature treatment discontinuation | 3 | (2.9) | 5 | 7.3 | 11 | (10.8) | 15 | 23.8 | 2 | (1.9) | 4 | 5.8 |

Abbreviations: E, number of events; N, number of participants experiencing at least one event; R, event rate per 100 years of exposure.

TEAEs include events with onset from first exposure to the follow‐up visit scheduled 5 weeks (+1 week visit window) after the last trial product dose.

The most frequently reported AEs were gastrointestinal (GI) events; namely constipation (14.6% and 11.8% for semaglutide 0.5 and 1.0 mg, respectively, vs 3.9% with sitagliptin), nausea (10.7% and 12.7%, vs none with sitagliptin) and diarrhoea (6.8% and 8.8%, vs 1.9% with sitagliptin; Table S4). GI events diminished over time (Figure S3).

3.3. Secondary efficacy endpoints

3.3.1. Glycaemic control

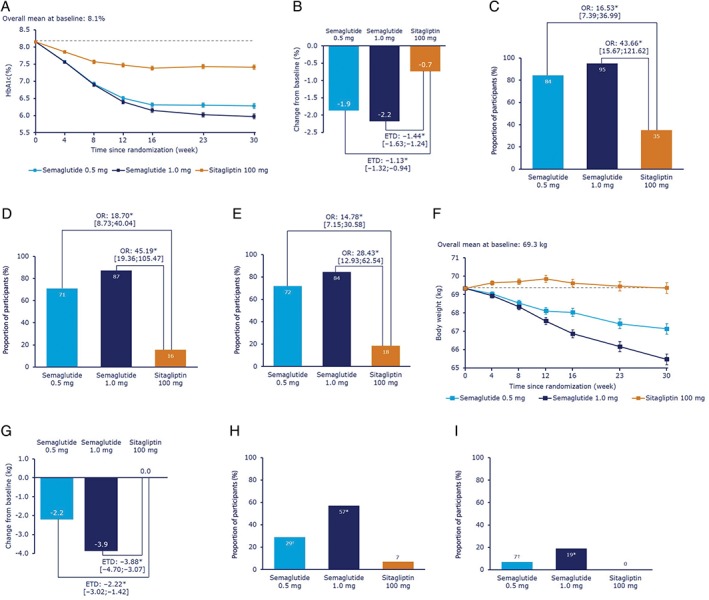

At week 30, mean HbA1c (baseline 8.1%) decreased by 1.9% and 2.2% with semaglutide 0.5 and 1.0 mg, respectively, vs 0.7% with sitagliptin (estimated treatment difference [ETD] vs sitagliptin −1.13%, 95% confidence interval [CI] −1.32; −0.94 and −1.44%, 95% CI −1.63; −1.24; both P < .0001 [Figure 2A,B and Table 3]). Statistical sensitivity analyses for change in HbA1c at week 30 supported the main analysis result (Figure S4A). The cumulative distribution of changes in HbA1c from baseline to week 30 indicated that greater proportions of participants treated with semaglutide 0.5 and 1.0 mg achieved improvements in glycaemic control compared with sitagliptin‐treated participants; nearly all participants treated with semaglutide attained improvements in glycaemic control (Figure S5A).

Figure 2.

Efficacy variables. Semaglutide 0.5 mg once weekly and 1.0 mg once weekly, compared with sitagliptin 100 mg once daily: mean HbA1c over time (A); change in mean HbA1c after 30 weeks (B); proportion of participants achieving HbA1c < 7.0% at 30 weeks (C); proportion of participants achieving HbA1c ≤ 6.5% at 30 weeks (D); proportion of participants achieving HbA1c < 7.0% with no severe or BG‐confirmed symptomatic hypoglycaemia and no weight gain at week 30 (E); mean body weight over time (F); change in mean body weight after 30 weeks (G); proportion of participants achieving ≥5% (H) or ≥10% (I) weight loss after 30 weeks. *Indicates significance (P < .0001); †indicates significance (P < .05). Values in A, B, F and G are estimated mean (± standard errors) from a MMRM using “on‐treatment without rescue medication” data from subjects in the full analysis set. Dotted line in A and F is the overall mean value at baseline. Values in C, D, H and I are proportions using “on‐treatment without rescue medication” data from subjects in the full analysis set. Missing data are imputed from a MMRM and subsequently classified.Abbreviations: BG, confirmed; BG <3.1 mmol/L; MMRM, mixed model for repeated measurements; OR, odds ratio.

Table 3.

Key outcomes by treatment group at week 30

| Semaglutide 0.5 mg | Semaglutide 1.0 mg | Sitagliptin 100 mg | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endpoint | Mean at baseline (±s.d.) | Change from baseline (s.e.) | ETD vs sitagliptin (95% CI) | P value vs sitagliptin | Change from baseline (s.e.) | ETD vs sitagliptin (95% CI) | P value vs sitagliptin | Change from baseline (s.e.) |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.1 (±0.9) | −1.9 (0.1) | −1.13 (−1.32; −0.94) | <.0001 | −2.2 (0.1) | −1.44 (−1.63; −1.24) | <.0001 | −0.7 (0.1) |

| Body weight (kg) | 69.3 (±13.8) | −2.2 (0.3) | −2.22 (−3.02; −1.42) | <.0001 | −3.9 (0.3) | −3.88 (−4.70; −3.07) | <.0001 | 0.0 (0.3) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.4 (±4.3) | −0.8 (0.1) | −0.84 (−1.13; −0.54) | <.0001 | −1.4 (0.1) | −1.44 (−1.74; −1.14) | <.0001 | 0.0 (0.1) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 89.7 (±10.8) | −2.4 (0.4) | −2.38 (−3.40; −1.37) | <.0001 | −3.8 (0.4) | −3.78 (−4.82; −2.74) | <.0001 | −0.1 (0.4) |

| BP (mmHg) | ||||||||

| Systolic | 129.1 (±14.8) | −5.3 (1.1) | −2.54 (−5.64; 0.55) | .1067 | −8.8 (1.2) | −6.01 (−9.16; −2.85) | .0002 | −2.8 (1.1) |

| Diastolic | 77.6 (±10.3) | −1.5 (0.7) | 0.12 (−1.97; 2.21) | .9072 | −3.6 (0.8) | −1.99 (−4.13; 0.16) | .0690 | −1.6 (0.8) |

| Pulse rate, bpm | 71.9 (±10.8) | 4.5 (0.8) | 3.41 (1.22; 5.59) | .0024 | 6.1 (0.8) | 4.94 (2.69; 7.19) | <.0001 | 1.1 (0.8) |

| Semaglutide 0.5 mg | Semaglutide 1.0 mg | Sitagliptin 100 mg | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | P value vs sitagliptin | N | (%) | P value vs sitagliptin | N | (%) | |

| HbA1c targets | ||||||||

| <7.0% | 87 | (84) | <.0001 | 97 | (95) | <.0001 | 36 | (35) |

| ≤6.5% | 73 | (71) | <.0001 | 89 | (87) | <.0001 | 16 | (16) |

| HbA1c target <7% with no severe or BG‐confirmed symptomatic hypoglycaemia and no weight gain at week 30 | 74 | (72) | <.0001 | 86 | (84) | <.0001 | 19 | (18) |

| Body weight reduction | ||||||||

| ≥5% | 30 | (29) | .0002 | 58 | (57) | <.0001 | 7 | (7) |

| ≥10% | 7 | (7) | .0141 | 19 | (19) | <.0001 | 0 | (0) |

Abbreviations: BG, blood glucose; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; bpm, beats per minute; CI, confidence interval; ETD, estimated treatment difference; MMRM, mixed model for repeated measurements; s.d., standard deviation; s.e., standard error.

Baseline is observed mean for the entire trial population. P values are 2‐sided testing the null hypothesis of no treatment difference. Changes from baseline (s.e.) and ETD are estimated values from MMRM. “On‐treatment without rescue medication” data from participants in the full analysis set, with the exception of pulse rate values, which are observed means using “on‐treatment” data from subjects in the safety analysis set. For treatment target endpoints, missing data are imputed from the MMRM and subsequently classified.

At week 30, the ADA‐ and JDS‐defined target (HbA1c <7.0%) was achieved by 84% and 95% of 0.5 and 1.0 mg semaglutide‐treated participants, respectively, vs 35% in the sitagliptin group (both P < .0001). At week 30, the AACE target (HbA1c ≤6.5%) was achieved by 71% and 87% of 0.5 and 1.0 mg semaglutide‐treated participants, respectively, vs 16% in the sitagliptin group (both P < .0001; Figure 2C,D and Table 3). Similarly, the proportion of participants achieving HbA1c <7.0% with no severe or BG‐confirmed symptomatic hypoglycaemia and no weight gain at week 30 was greater with semaglutide than with sitagliptin (72% and 84% vs 18%, respectively; P < .0001 for both; Figure 2E and Table 3).

Reductions in mean FPG were significantly greater with semaglutide than with sitagliptin: 2.8 and 3.3 mmol/L with semaglutide 0.5 and 1.0 mg, respectively, vs 1.3 mmol/L with sitagliptin (ETD −1.47 mmol/L [95% CI −1.78; −1.16] and −1.99 mmol/L [95% CI −2.30; −1.67], respectively; both P < .0001).

Mean 7‐point SMPG values significantly decreased with both semaglutide doses vs sitagliptin (ETD −1.66 mmol/L [95% CI −2.09; −1.23] and −2.24 mmol/L [95% CI −2.68; −1.80], respectively; both P < .0001). Similarly, there was a significant reduction in the SMPG postprandial increment with semaglutide vs sitagliptin (ETD −0.78 mmol/L [95% CI −1.27; −0.29] and −1.44 mmol/L [95% CI −1.95; −0.94], respectively; P = .0020 and P < .0001).

3.3.2. Body weight

At week 30, body weight (baseline 69.3 kg) was reduced by 2.2 and 3.9 kg with semaglutide 0.5 and 1.0 mg, respectively, vs no reduction with sitagliptin (ETD −2.22 kg, 95% CI −3.02; −1.42, and −3.88 kg, 95% CI −4.70; −3.07; both P < .0001 [Figure 2F and G and Table 3]). Sensitivity analyses for change in body weight at week 30 supported the main analysis result (Figure S4B). The cumulative distribution of changes in body weight from baseline to week 30 indicated that greater proportions of participants treated with semaglutide 0.5 and 1.0 mg achieved reductions in weight compared with sitagliptin‐treated participants; most semaglutide‐treated participants achieved weight loss (Figure S5B).

A weight loss of ≥5% was achieved by 29% and 57% of 0.5 and 1.0 mg semaglutide‐treated participants, respectively, vs 7% in the sitagliptin group (P < .0002 and P < .0001, respectively). A weight loss of ≥10% was achieved by 7% and 19% of 0.5 and 1.0 mg semaglutide‐treated participants, respectively, vs 0% in the sitagliptin group (P .0141 and P < .0001, respectively) (Figure 2H and I, and Table 3).

3.3.3. Other efficacy endpoints

Treatment with semaglutide 0.5 and 1.0 mg reduced BMI and waist circumference, compared with sitagliptin (P < .0001 for both). In addition, decreases in BP were generally greater with semaglutide 1.0 mg than with sitagliptin. The difference in systolic BP with semaglutide 1.0 mg, vs sitagliptin, was significant (ETD −6.01 mmHg, 95% CI −9.16; −2.85; P = .0002); there was no significant difference in diastolic BP (Table 3).

Total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol were significantly reduced with both semaglutide doses, whereas VLDL cholesterol and triglycerides were significantly reduced with semaglutide 1.0 mg vs sitagliptin. There was no significant difference in change in HDL cholesterol or FFA levels between semaglutide and sitagliptin (Figure S6).

3.4. Supportive secondary safety endpoints

No severe episodes of hypoglycaemia were reported in any treatment group. One hypoglycaemic episode, classified as “severe or BG‐confirmed symptomatic,” was reported in the semaglutide 1.0 mg group (Table S5). This event was symptomatic and plasma glucose level was 2.6 mmol/L.

No EAC‐confirmed pancreatitis events were reported. Mean levels of pancreatic enzymes (lipase and amylase) increased for both semaglutide doses vs sitagliptin. One participant treated with semaglutide 1.0 mg experienced cholelithiasis (Table S5), which did not lead to premature treatment discontinuation. There were 2 EAC‐confirmed cardiovascular events in the semaglutide 0.5 mg group (Table S5; 1 event of silent myocardial infarction; 1 of percutaneous revascularization).

Pulse (baseline 71.9 bpm) increased in all 3 groups (ETD 3.41 bpm [95% CI 1.22; 5.59] and 4.94 bpm [95% CI 2.69; 7.19] for semaglutide 0.5 and 1.0 mg vs sitagliptin, respectively; P = .0024 and P < .0001 [Table 3]).

Overall, 2 EAC‐confirmed malignant neoplasms were reported; 1 with semaglutide 1.0 mg (malignant low‐grade bladder cancer tumour) and 1 with sitagliptin (malignant pancreatic carcinoma stage IV). The participant in the semaglutide 1.0 mg arm completed treatment; the sitagliptin‐treated participant discontinued treatment. No malignant neoplasms were reported with semaglutide 0.5 mg (Table S5). No EAC‐confirmed thyroid neoplasms or medullary thyroid carcinomas were reported. Calcitonin levels were similar between groups with no apparent change during the trial.

Nervous system disorders were reported by 12 participants (11.7%) in the semaglutide 0.5 mg group, none in the semaglutide 1.0 mg group and 5 (4.9%) in the sitagliptin group (Table S5), and were composed of single unrelated AEs.

One semaglutide 1.0 mg‐treated participant developed anti‐semaglutide antibodies; however, there was no cross‐reaction with endogenous GLP‐1. At follow‐up, the participant tested antibody‐negative and therefore no in vitro neutralizing effect was assessed.

There were 4 reported events of diabetic retinopathy in the semaglutide 0.5 mg group, 2 events in the semaglutide 1.0 mg group, and 4 events in the sitagliptin group.

There were no clinically relevant changes in other safety laboratory assessments, physical examinations or electrocardiograms.

4. DISCUSSION

The results of the present trial showed that, in Japanese participants with T2D, more participants receiving semaglutide reported TEAEs than with sitagliptin. This was driven mainly by GI AEs, a well‐known side effect of GLP‐1 RAs. The discontinuation rate was low and similar between semaglutide 0.5 mg and sitagliptin, but was higher with semaglutide 1.0 mg, owing to a larger proportion of participants experiencing GI AEs. The slightly higher rate of constipation vs nausea and diarrhoea than reported in global trials may have been influenced by other factors, such as differences in diet, cultural differences in how constipation is defined or reported, or AE‐reporting bias among participants. The frequency of GI AEs diminished over time, as observed with other GLP‐1 RAs and other studies with semaglutide.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 24, 25 Dose escalation of GLP‐1 RAs has also previously been shown to partially ameliorate GI AEs, as reflected in the design of this trial.26

In general, the AE profile of semaglutide was similar to that of other GLP‐1 RAs5; for example, in addition to GI AEs, a commonly reported TEAE was increased levels of pancreatic enzymes for both semaglutide doses vs sitagliptin (although no pancreatitis events were reported). Pancreatitis cases have previously been reported in exenatide‐treated patients and in other clinical development programmes for GLP‐1 RAs and other incretin‐based drugs,27, 28 although retrospective analyses suggest there is no increased risk of acute cases.29, 30, 31, 32 In addition, reduced appetite was frequently reported in semaglutide‐treated participants. This is a class effect, as GLP‐1 receptors are expressed in the hypothalamus, the region of the brain that regulates satiety and appetite. Effectively, this is thought to be the mechanism that enables GLP‐1 RAs to lower energy intake, thereby reducing body weight,33, 34 although to a varying degree. The increase in pulse rate reported with semaglutide treatment has also been previously reported in, for example, liraglutide‐ and exenatide‐treated participants,24, 35 although the potential mechanisms behind this haemodynamic effect are unclear.36

Compared with sitagliptin 100 mg monotherapy, both semaglutide 0.5 and 1.0 mg monotherapy significantly improved glycaemic control (change in HbA1c: −1.9%, −2.2% vs −0.7%, respectively) and reduced body weight (−2.2 kg, −3.9 kg vs 0.0 kg, respectively). These improvements were sustained over 30 weeks of treatment, and were supported by the sensitivity analyses. Furthermore, significantly greater proportions of participants receiving semaglutide achieved the ADA and JDS target of HbA1c <7.0% vs sitagliptin (84% and 95% of 0.5 and 1.0 mg semaglutide‐treated participants, respectively, vs 35% in the sitagliptin group). Importantly, a higher proportion of participants treated with semaglutide than with sitagliptin achieved this target with no severe or BG‐confirmed symptomatic hypoglycaemia and no weight gain at week 30 (72% and 84% vs 18%, respectively). Semaglutide’s efficacy relating to body weight was also evident compared with sitagliptin, with greater proportions of participants achieving body weight loss of ≥5% (29% and 57% vs 7%, respectively) and ≥10% (7% and 19% vs 0%, respectively).

These findings are consistent with the global SUSTAIN trials, in which semaglutide was associated with clinically meaningful and superior reductions in HbA1c and body weight vs placebo (SUSTAIN 1 and SUSTAIN 5 [add‐on to insulin]),10, 14 sitagliptin (SUSTAIN 2)11 – all multinational trials that included Japan, exenatide ER (SUSTAIN 3),12 and insulin glargine (SUSTAIN 4).13 The findings also align with trials of liraglutide in participants with T2D, where significant reductions in HbA1c and body weight were observed, either compared with placebo or a thiazolidinedione, all when added to a sulphonylurea24 ; or compared with placebo or a sulphonylurea, all on a background of metformin.25 In addition, similar results have been observed with other GLP‐1 RAs, such as albiglutide37 and dulaglutide,38 either compared with placebo or active comparators such as sitagliptin or insulin glargine, as monotherapy or add‐on therapy to other antidiabetic agents.

In the present trial, semaglutide also resulted in marked improvements in cardiometabolic risk compared with sitagliptin, and included reductions in BMI, waist circumference and BP, and improvements in most lipid level profiles. In SUSTAIN 6, semaglutide was associated with a significant 26% reduction in cardiovascular risk (primary composite outcome of death from cardiovascular causes, non‐fatal myocardial infarction or non‐fatal stroke) compared with placebo in a standard‐of‐care setting.15

Baseline characteristics, although similar across the 3 treatment groups, differed slightly from the global SUSTAIN trials. In this trial population, baseline body weight and BMI were markedly lower than in participants from various ethnic groups in the global trials, reflecting an overall leaner population.

Furthermore, more marked reductions in HbA1c were reported in this trial than in the SUSTAIN 1 to 5 trials.10, 11, 12, 13, 14 The reasons for this difference between the present trial and SUSTAIN 1 to 5 are unclear; however, these results are in line with a recent meta‐analysis in which GLP‐1 analogues were associated with greater HbA1c reductions and a higher proportion of participants achieving HbA1c target ≤7% in Asian (including Japanese) vs non‐Asian populations.39

Participants in this trial had a mean baseline diabetes duration of 8.0 years, similar to the global SUSTAIN 2 trial (6.6 years), but early initiation of treatment may be beneficial in Asian people to provide sustained glycaemic control and avoid long‐term diabetes complications. Although body weight was reduced with semaglutide in this trial, greater reductions were reported in the SUSTAIN 1 to 5 trials (3.5–4.3 kg with semaglutide 0.5 mg; 4.5–6.4 kg with semaglutide 1.0 mg).10, 11, 12, 13, 14 Both baseline body weight and BMI were lower in this trial population, by ~20 kg and 7 kg/m2, respectively; thus, the body weight reductions of 3.3% and 5.7% with semaglutide 0.5 and 1.0 mg, respectively, should be considered in this context. It might be expected that Japanese participants would lose less body mass overall than a heavier and/or obese cohort, as ~80% of weight lost with semaglutide treatment is fat mass.40 This, together with the influence of the Japanese diet, may have affected the overall change in body weight in this trial.

These efficacy results might also be considered in the context that, in East Asia, T2D is characterized by significant β‐cell dysfunction with less adiposity and less insulin resistance than in Western populations. Consequently, incretin‐based drugs may show more efficacy in Asian populations, mostly because of amelioration of β‐cell dysfunction.41, 42

The open‐label design of this trial is a limitation, increasing the risk of bias. The relatively short trial duration is also a limitation, as the full potential of semaglutide with regard to durability, efficacy and safety may not have been observed over 30 weeks. In addition, approximately three‐quarters of the total trial population was male and, as such, may not accurately reflect the T2D population in Japan. Differential results between men and women with T2D, however, would not be expected. Furthermore, the authors acknowledge that GLP‐1 RAs are not usually considered for monotherapy; neither is sitagliptin the most frequently used monotherapeutic oral agent in Japan. Thus, in clinical practice, both semaglutide and sitagliptin would probably be given in combination with metformin, and the applicability of the results should be interpreted in this context, whereby the treatment regimens described may not reflect mainstream practice in the T2D population in Japan. Nevertheless, the SUSTAIN programme as a whole covered a broad spectrum of patients with T2D10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 ; for example, SUSTAIN 2, which included patients from Japan, investigated semaglutide vs sitagliptin as an add‐on to metformin.11 It should be noted that, in line with regulatory requirements, this trial was designed to assess these treatments as monotherapy, in order to investigate the safety and efficacy of each in isolation. Finally, the collection of body composition data would have been useful, to clarify whether the observed body weight loss with semaglutide was caused by loss of fat or lean body mass. A recently published study involving semaglutide treatment in obese participants has, however, demonstrated that semaglutide is associated with a 3‐fold greater loss of fat over lean body mass compared with placebo.40

Despite these limitations, the significant reductions in HbA1c and body weight observed in this trial indicate the potential for semaglutide as a treatment option in Japanese participants with T2D. This is important given that many other treatments are either weight‐neutral or associated with weight gain.43, 44, 45

In conclusion, in Japanese participants with T2D, more TEAEs were reported with semaglutide (0.5 and 1.0 mg) than with sitagliptin, but semaglutide was well tolerated, with a safety profile similar to that of other GLP‐1 RAs. Semaglutide had a greater effect on glycaemic control, body weight reduction and other efficacy variables vs sitagliptin 100 mg monotherapy.

ORCID

Yutaka Seino http://orcid.org/0000‐0002‐1099‐7989

Supporting information

Figure S1. Trial design.

Figure S2. Cumulative incidence of premature discontinuation of treatment due to adverse events over time.

Figure S3. Time course of constipation (A), nausea (B) and diarrhoea (C) from baseline to 35 weeks.

Figure S4. Statistical sensitivity analyses for estimated treatment differences in HbA1c (A) and body weight (B) at week 30.

Figure S5. Cumulative distribution of change from baseline in HbA1c (A) and body weight (B) to week 30.

Figure S6. Estimated treatment ratios for lipid levels from baseline to 30 weeks.

Table S1. Key inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table S2. Events types predefined for Event Adjudication Committee review.

Table S3. Treatment‐emergent serious adverse events (by system organ class).

Table S4. Most frequent treatment‐emergent adverse events (≥5% of subjects in any group).

Table S5. Additional treatment‐emergent adverse events of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all the participants, investigators and trial‐site staff who were involved in the conduct of the trial. We also thank Sayeh Tadayon and Hrvoje Vrazic (Novo Nordisk) for their review and input to the manuscript, and Sola Neunie, MSc, CMPP (AXON Communications) for medical writing and editorial assistance, who received compensation from Novo Nordisk.

Conflict of interest

Y.S. has received honoraria for consulting and/or speakers bureau from Kao; Kyowa Hakko Kirin; Taisho Pharmaceutical; Becton, Dickinson and Company; Novo Nordisk; MSD; Intarcia Therapeutics; Johnson & Johnson; GlaxoSmithKline; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; Sanofi; Taisho Toyama Pharmaceutical; Eli Lilly & Company; Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma; Ono Pharmaceutical; Kowa; Astellas Pharma; Boehringer Ingelheim; AstraZeneca; Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma; Daiichi Sankyo; Terumo; Arkray; and clinical commissioned/joint research grants from Arkray Marketing; Kowa; Hayashibara; Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim; Eli Lilly & Company; Terumo; Taisho Toyama Pharmaceutical; MSD K.K.; Ono Pharmaceutical; Novo Nordisk; Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma; Arklay. Y. T. has received honoraria for speakers bureau from Astellas Pharma; AstraZeneca K.K.; Bayer Yakuhin; Daiichi Sankyo; Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma; Eli Lilly Japan K.K.; Kowa; MSD K.K.; Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma; Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim; Novo Nordisk; Ono Pharmaceutical; Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusho; Sanofi K.K.; Shionogi & Company; Taisho Toyama Pharmaceutical; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and grants from Astellas Pharma; AstraZeneca K.K.; Bayer Yakuhin; Daiichi Sankyo; Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma; Eli Lilly Japan K.K.; Kowa; MSD K.K.; Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma; Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim; Novo Nordisk; Ono Pharmaceutical; Pfizer Japan; Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusho; Sanofi K.K., Shionogi & Company; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company. T. O. is a lecturer and clinical study investigator for Novo Nordisk. D. Y. has received consulting and/or speaker fees from MSD K.K.; Novo Nordisk; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; Taisho Toyama Pharmaceutical; and clinical commissioned/joint research grants from Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim; Eli Lilly & Company; Taisho Toyama Pharmaceutical; MSD K.K.; Ono Pharmaceutical; Novo Nordisk; Arklay; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company. NA has no conflicts of interest. T.N. is an employee of Novo Nordisk and holds shares in the company. J. Z. is an employee of Novo Nordisk and holds shares in the company. S. K. has received honoraria for speakers bureau from Astellas Pharma; AstraZeneca K.K.; Daiichi Sankyo; Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma; Eli Lilly Japan K.K.; Kissei Pharmaceutical; Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma; Novo Nordisk; Novartis Pharma K.K.; Ono Pharmaceutical; Sanofi K.K.; Taisho Toyama Pharmaceutical; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and grants from WebMD Global LLC.

Author contributions

Y.S.: study design, study conduct/data collection, writing the manuscript; Y.T.: study conduct/data collection, data analysis, writing the manuscript; T.O.: data collection; D.Y.: study conduct/data collection, data analysis, writing the manuscript; N.A.: study conduct/data collection, reviewing the manuscript; T.N.: study design, data analysis, writing the manuscript; J.Z.: study design, study conduct/data collection, data analysis, writing the manuscript; S.K.: study conduct/data collection, data analysis, writing the manuscript.

Seino Y., Terauchi Y., Osonoi T. et al. Safety and efficacy of semaglutide once weekly vs sitagliptin once daily as monotherapy in Japanese people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:378–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.13082

Funding information This trial was supported by Novo Nordisk A/S; NCT02254291.

REFERENCES

- 1. Mukai N, Doi Y, Ninomiya T, et al. Trends in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes and prediabetes in community‐dwelling Japanese subjects: the Hisayama Study. J Diabetes Invest. 2014;5(2):162–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stark Casagrande S, Fradkin JE, Saydah SH, Rust KF, Cowie CC. The prevalence of meeting A1c, blood pressure, and LDL goals among people with diabetes, 1988–2010. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(8):2271–2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Handelsman Y, Bloomgarden ZT, Grunberger G, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology – clinical practice guidelines for developing a diabetes mellitus comprehensive care plan – 2015. Endocr Pract. 2015;21(suppl 1):1–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient‐centered approach: update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(1):140–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Prasad‐Reddy L, Isaacs D. A clinical review of GLP‐1 receptor agonists: efficacy and safety in diabetes and beyond. Drugs Context. 2015;4:212283 https://doi.org/10.7573/dic.212283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kapitza C, Nosek L, Jensen L, et al. Semaglutide, a once‐weekly human GLP‐1 analog, does not reduce the bioavailability of the combined oral contraceptive, ethinylestradiol/levonorgestrel. J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;55(5):497–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marbury TC, Flint A, Segel S, Lindegaard M, Lasseter KC. Abstracts of the 50th EASD Annual Meeting, September 15–19, 2014, Vienna, Austria. Diabetologia. 2014;57(suppl 1):S358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Inukai K, Hirata T, Sumita T, et al. Clinical characteristics of Japanese type 2 diabetic patients responsive to sitagliptin. J Diabetes Mellitus. 2014;4:172–178. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Seino Y, Yabe D. Glucose‐dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and glucagon‐like peptide‐1: incretin actions beyond the pancreas. J Diabetes Investig. 2013;4(2):108–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sorli C, Harashima SI, Tsoukas GM, et al. Efficacy and safety of once‐weekly semaglutide monotherapy versus placebo in patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 1): a double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled, parallel‐group, multinational, multicentre phase 3a trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(4):251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ahrén B, Masmiquel L, Kumar H, et al. Efficacy and safety of once‐weekly, subcutaneous semaglutide versus oral sitagliptin as add‐on to metformin and/or thiazolidinediones in subjects with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 2): a 56‐week randomised, controlled clinical trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(5):341–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ahmann AJ, Capehorn M, Charpentier G, et al. Efficacy and safety of once‐weekly semaglutide vs exenatide ER after 56 weeks in subjects with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 3). American Diabetes Association – 76th Annual Scientific Sessions; New Orleans, LA, USA, 2016;65(suppl 1):A49. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aroda VR, Bain SC, Cariou B, et al. Efficacy and safety of once‐weekly semaglutide versus once‐daily insulin glargine as add‐on to metformin (with or without sulphonylureas) in insulin‐naive patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 4): a randomised, open‐label, parallel‐group, multicentre, multinational, phase 3a trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(5):355–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rodbard H, Lingvay I, Reed J, et al. Efficacy and safety of semaglutide once‐weekly vs placebo as add‐on to basal insulin alone or in combination with metformin in subjects with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 5). Diabetologia. 2016;59(suppl 1):S364–S365. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;10(375):1834–1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. ClinicialTrials.gov . A trial comparing the safety and efficacy of semaglutide once weekly in monotherapy or in combination with one OAD in Japanese subjects with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN™). 2014. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02207374. Accessed September 20, 2017.

- 17. ClinicialTrials.gov . A trial comparing the safety and efficacy of semaglutide once weekly versus sitagliptin once daily in Japanese subjects with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN™). 2014. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02254291. Accessed September 20, 2017.

- 18. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare . Guideline for Clinical Evaluation of Oral Hypoglycaemic Agents. 2010. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency, Tokyo, Japan. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000208194.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19. European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products . International Conference on Harmonisation‐World Health Organization guideline for good clinical practice [EMEA Web site] ICH harmonised tripartite guideline good clinical practice. 2016. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500002874.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2017.

- 20. World Medical Association . Declaration of Helsinki ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Last amended by the 59th WMA General Assembly, Seoul, Republic of Korea. 2008. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/. Accessed September 20, 2017.

- 21. Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. Consensus statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm – 2017 executive summary. Endocr Pract. 2017;23:207–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. American Diabetes Association . Standards of medical care in diabetes – 2016. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(suppl 1):S1–S112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. The Japan Diabetes Society . Evidence‐based practice guideline for the treatment for diabetes in Japan 2013. http://www.jds.or.jp/modules/en/index.php?content_id=44. Accessed September 20, 2017.

- 24. Marre M, Shaw J, Brändle M, et al. Liraglutide, a once‐daily human GLP‐1 analogue, added to a sulphonylurea over 26 weeks produces greater improvements in glycaemic and weight control compared with adding rosiglitazone or placebo in subjects with Type 2 diabetes (LEAD‐1 SU). Diabet Med. 2009;26(3):268–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nauck M, Frid A, Hermansen K, et al. Efficacy and safety comparison of liraglutide, glimepiride, and placebo, all in combination with metformin, in type 2 diabetes: the LEAD (liraglutide effect and action in diabetes)‐2 study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(1):84–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nauck MA, Petrie JR, Sesti G, et al. A phase 2, randomized, dose‐finding study of the novel once‐weekly human GLP‐1 analog, semaglutide, compared with placebo and open‐label liraglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(2):231–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ahmad SR, Swann J. Exenatide and rare adverse events. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(18):1970–1971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cefalu WT, Buse JB, Del Prato S, et al. Beyond metformin: safety consideration in the decision making process for selecting a second medication for type 2 diabetes management. Reflections from a diabetes care editors' expert forum. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(9):2647–2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Garg R, Chen W, Pendergrass M. Acute pancreatitis in type 2 diabetes treated with exenatide or sitagliptin: a retrospective observational pharmacy claims analysis. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(11):2349–2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dore DD, Seeger JD, Arnold CK. Use of a claims‐based active drug safety surveillance system to assess the risk of acute pancreatitis with exenatide or sitagliptin compared to metformin or glyburide. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(4):1019–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dore DD, Bloomgren GL, Wenten M, et al. A cohort study of acute pancreatitis in relation to exenatide use. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13(6):559–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wenten M, Gaebler JA, Hussein M, et al. Relative risk of acute pancreatitis in initiators of exenatide twice daily compared with other antidiabetic medication: a follow‐up study. Diabet Med. 2012;29(11):1412–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Flint A, Raben A, Astrup A, Holst JJ. Glucagon‐like peptide 1 promotes satiety and suppresses energy intake in humans. J Clin Invest. 1998;101(3):515–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Secher A, Jelsing J, Baquero AF, et al. The arcuate nucleus mediates GLP‐1 receptor agonist liraglutide‐dependent weight loss. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(10):4473–4488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kothare PA, Linnebjerg H, Isaka Y, et al. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, tolerability, and safety of exenatide in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;48(12):1389–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gustavson SM, Chen D, Somayaji V, et al. Effects of a long‐acting GLP‐1 mimetic (PF‐04603629) on pulse rate and diastolic blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13(11):1056–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Blair HA, Keating GM. Albiglutide: a review of its use in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Drugs. 2015;75(6):651–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jendle J, Grunberger G, Blevins T, Giorgino F, Hietpas RT, Botros FT. Efficacy and safety of dulaglutide in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a comprehensive review of the dulaglutide clinical data focusing on the AWARD phase 3 clinical trial program. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016;32(8):776–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kim YG, Hahn S, Oh TJ, Park KS, Cho YM. Differences in the HbA1c‐lowering efficacy of glucagon‐like peptide‐1 analogues between Asians and non‐Asians: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16(10):900–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Blundell J, Finlayson G, Buhl Axelsen M, et al. Effects of once‐weekly semaglutide on appetite, energy intake, control of eating, food preference and body weight in subjects with obesity. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19(9):1242–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Seino Y, Kuwata H, Yabe D. Incretin‐based drugs for type 2 diabetes: focus on East Asian perspectives. J Diabetes Investig. 2016;7(suppl 1):102–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yabe D, Seino Y. Type 2 diabetes via β‐cell dysfunction in East Asian people. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4(1):2–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Riddle MC, Rosenstock J, Gerich J, Insulin Glargine 4002 Study Investigators . The treat‐to‐target trial: randomized addition of glargine or human NPH insulin to oral therapy of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(11):3080–3086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kahn SE, Haffner SM, Heise MA, et al. Glycemic durability of rosiglitazone, metformin, or glyburide monotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(23):2427–2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group . Intensive blood‐glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet. 1998;352(9131):837–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Trial design.

Figure S2. Cumulative incidence of premature discontinuation of treatment due to adverse events over time.

Figure S3. Time course of constipation (A), nausea (B) and diarrhoea (C) from baseline to 35 weeks.

Figure S4. Statistical sensitivity analyses for estimated treatment differences in HbA1c (A) and body weight (B) at week 30.

Figure S5. Cumulative distribution of change from baseline in HbA1c (A) and body weight (B) to week 30.

Figure S6. Estimated treatment ratios for lipid levels from baseline to 30 weeks.

Table S1. Key inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table S2. Events types predefined for Event Adjudication Committee review.

Table S3. Treatment‐emergent serious adverse events (by system organ class).

Table S4. Most frequent treatment‐emergent adverse events (≥5% of subjects in any group).

Table S5. Additional treatment‐emergent adverse events of interest.