Abstract

Background and purpose

Implementation of contextually appropriate, evidence-based, expert-recommended stroke prevention guideline is particularly important in Low-Income Countries (LMICs), which bear disproportional larger burden of stroke while possessing fewer resources. However, key quality characteristics of guidelines issued in LMICs compared with those in High-Income Countries (HICs) have not been systematically studied. We aimed to compare important features of stroke prevention guidelines issued in these groups.

Methods

We systematically searched PubMed, AJOL, SciELO, and LILACS databases for stroke prevention guidelines published between January 2005 and December 2015 by country. Primary search items included: “Stroke” and “Guidelines”. We critically appraised the articles for evidence level, issuance frequency, translatability to clinical practice, and ethical considerations. We followed the PRISMA guidelines for the elaboration process.

Results

Among 36 stroke prevention guidelines published, 22 (61%) met eligibility criteria: 8 from LMICs (36%) and 14 from HICs (64%). LMIC-issued guidelines were less likely to have articulation of recommendations (62% vs. 100%, p = 0.03), involve high quality systematic reviews (21% vs. 79%, p = 0.006), have a good dissemination channels (12% vs 71%, p = 0.02) and have an external reviewer (12% vs 57%, p = 0.07). The patient views and preferences were the most significant stakeholder considerations in HIC (57%, p = 0.01) compared with LMICs. The most frequent evidence grading system was American Heart Association (AHA) used in 22% of the guidelines. The Class I/III and Level (A) recommendations were homogenous among LMICs.

Conclusions

The quality and quantity of stroke prevention guidelines in LMICs are less than those of HICs and need to be significantly improved upon.

Keywords: Stroke, Primary prevention, Secondary prevention, Guideline, Practice guideline, Developing countries

1. Introduction

Stroke continues to be an important public health problem worldwide. Between 1990 and 2013, stroke disease and mortality burdens increased due to demographic and epidemiological transitions in developing countries [3]. Using the World Bank's classification system, Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) contribute over 87% of stroke mortality [4]. Immediate post-stroke mortality and long-term disability significantly worsens an already poor economy in these countries. Focus therefore, should be on approaches enabling healthcare systems to improve control of vascular risk factors [5,6]. However, published data on stroke are limited in LMICs, making it difficult to recognize and evaluate the risk factors and significant issues (eg, renal disease, diet, infections) comprising the total disease burden, and to strategically implement intervention and mitigation on whole populations [7]. Of note is the fact that differences in post-stroke care accessibility may account for a portion of the higher LMIC stroke burden [8].

Developing improved standards of care is one of the World Health Organization's (WHO) goals as part of the Global Action Plan [9,10]. However, LMICs display wide variations in stroke care delivery [2]. The differences in care quality are explainable by knowledge and skill gaps in professionals, limited resources, or locally different available levels of stroke care [2,11]. The preferred approach of achieving this may be through primary stroke-prevention strategies involving efforts of national, provincial, and local governments and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), as well as eleemosynary organizations in cooperation with international agencies [12].

In this study, we aimed to outline available LMIC stroke-prevention guidelines and compare them with similar HIC guidelines. We analyzed availability in various countries. For LMICs, we compared the re-issue frequency, guideline quality, as well as the strength and level of evidence-based recommendations. Additionally, we compared the time lag between a study and the resulting guideline relative to HIC landmark studies supporting specific recommendations. The comparison of guidelines between LIMCs and HICs are mainly focused on (a) Guidelines Published; (b) Guideline Re-issue Frequency; (c) Guideline age relative to landmark clinical studies; (d) Rigor of evidence-based recommendations, Level of Evidence (LOE), and (e) Recommendations based on local population evidence.

2. Methods

We systematically searched PubMed, AJOL, SciELO, and LILACS using as primary search terms “stroke” and “guidelines”, for publication dates between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2015. Secondary search terms included “clinical practice”, “translation”, and “prevention”. Tertiary search items included, “World Health Organization”, “United States”, “American”, “International”, “European”, “African”, “Asian”, “Japanese”, “South American”, “Society”, “Association”, “League”, and “Group” (searches included usual abbreviations). Since there is no specific public database for LMIC stroke prevention guidelines, we also similarly searched the World Stroke Organization (WSO) [13] and for HIC guidelines in the National Institute of Clinical Excellence [14] and Open Clinical [15]. The most recent search was May 31, 2016. We also searched websites of stroke organizations in specific countries (eg, US, Canada, UK, Australia, New Zealand, Malaysia, etc.). Finally, we manually searched references of literature recently found in the above-described digital search. We followed the PRISMA guidelines to elaboration of the systematic review [16].

Firstly, in our evaluation we screened titles, “scientific rationale”, “scientific statements”, “recommendations”, “consensus statements”, “healthcare professional's statements”, “performance”, “guidance”, “policy statements”, “scientific advisory statements”, “stroke management” articles, and “stroke prevention” articles mentioning “ischemic cerebrovascular disease” or “stroke”. We did this to ensure we had identified documents appropriately.

Secondly, we applied the following inclusion criteria:

Clinical Practice Guidelines – ischemic stroke prevention,

Ischemic Stroke-Prevention – included in the body of the guideline or as a guideline chapter,

Written For A Specific Country,

Elaboration – specific country elaboration for physicians/associations,

- Exclusion Criteria Included:

- Guideline Compliance

- Implementation or Adherence

- Abstract, letter, or comment about stroke, ischemic prevention guidelines

- Analysis of Published Guidelines

- Previous Versions of The Guideline (only the most recent version was included).

Thirdly, we summarized the evidence into several tables for ease of understanding. Guideline quality was assessed using the Institute of Medicine (IOM) consensus report standards [17]. Every IOM standard was scored using a previously described system between 0 and 3 [18]. Where 0 = the standard was not mentioned, 1 = standard with low confidence, 2 = standard with moderate confidence and 3 = standard with high confidence was followed by the guideline developers. We chose as a positive domain or standard a score ≥ 2. Guideline data was extracted to understand the classification system used, to qualify evidence, for strength of recommendations, and to examine expertise level of Task Force members. From these searches, we expanded our study to include selection methods, the best recommendations, and summarized the evidence by specific geographical areas.

We reviewed all the citations for the chosen recommendations – publication year, country/countries, target populations for a specific studies, and the projected revision date for each guideline. We also examined guidelines regarding stakeholder involvement, translatability into clinical practice, ethical, social, and legal considerations. Finally, we added a new evaluation criterion-mitigation planning. It is our strong opinion that guidelines lacking mitigation plans cannot be effectively implemented anywhere.

We performed a descriptive analysis of the number of available guidelines. Based on the main findings on evidence tables, we performed 2 × 2 matrices (HIC/LMIC and yes/no) to extract the data and compared results in the HICs with those in LMICs using Chi-square or Fisher's exact Test for the categorical variables using STATA 11.2.

3. Results

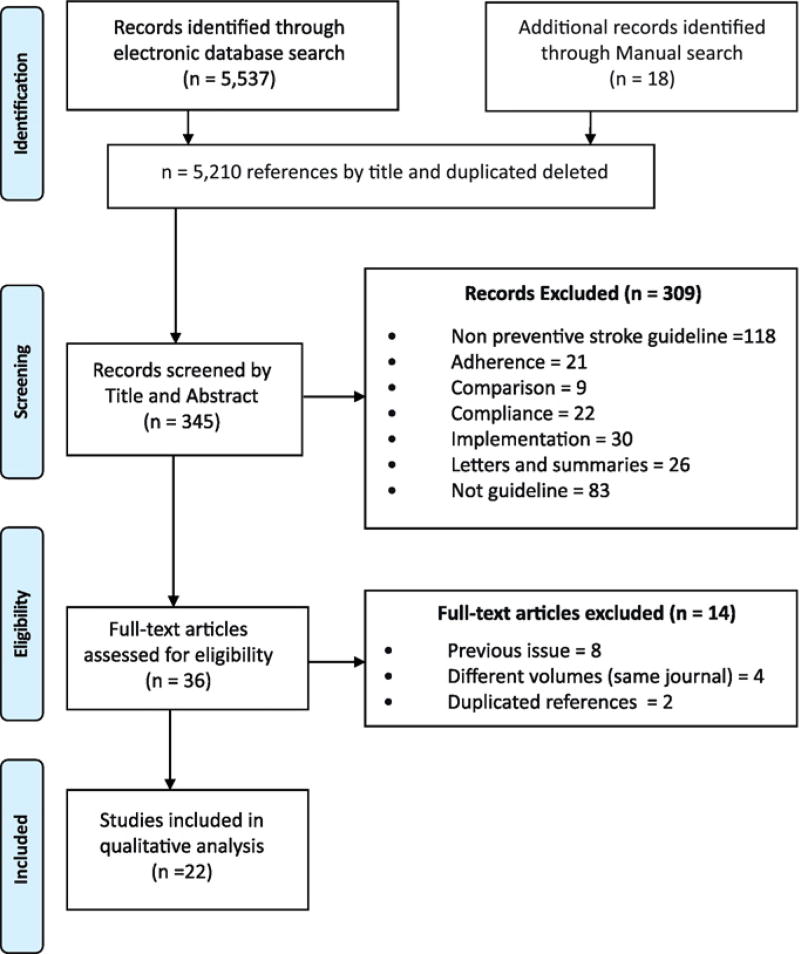

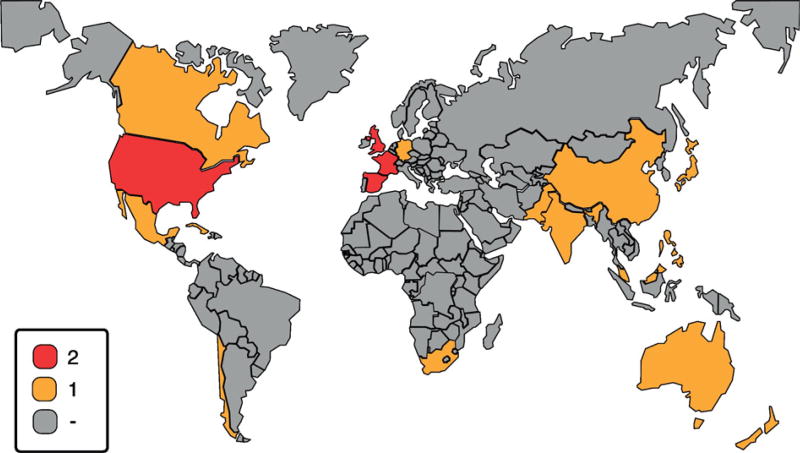

We identified 5537 titles through our search. Additionally, we found an additional 18 titles manually. After applying inclusion criteria by title in the screening phase, we discarded 5210 articles as irrelevant. We assessed for eligibility 345 individual documents by applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria using the PRISMA methodology. Then we narrowed the field to 36 relevant stroke-prevention guidelines for full textual evaluation. After disallowing previous versions of the same guideline, duplicated references and different chapters in the same guideline published in the same journal volume, only 22 guidelines qualified for inclusion in our final analysis (Fig.1). Of these, 14 guidelines were published in HICs and 8 in LMICs. We consolidated the key features for each guideline including publication year, previous reviews of the same guideline in the search timeframe, and the prevention type. Of these, 14 guidelines were published in HICs and 8 in LMICs. The results were identified by country/countries with 3/22 guidelines from Lower-Middle countries (14%) and 5/22 from Upper-Middle countries (22%) (Fig.2). We evaluated the “trustworthiness” of each guideline using the IOM [17] standards (Table 1) which determine whether the development of the guideline was based on best practices.

Fig. 1.

Identification of stroke prevention guidelines.

Fig. 2.

Worldwide stroke prevention guideline availability Guideline availability by country, red color denotes at least two guidelines published in the researched period. The yellow color means one guideline publication and the gray zones represent absence of a stroke prevention guideline for the 2005–2015 period. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Table 1.

Criteria for trustworthy clinical practice guidelines (IOM).

| Guideline | Stand'd 1 Funding identified |

Stand'd 2 COI Mgmt |

Stand'd 3 Multi-discipline |

Stand'd 4 System reviews |

Stand'd 5 Evidence rating |

Stand'd 6 Rec'md strength |

Stand'd 7 External review |

Stand'd 8 Re-issue date |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Clinical Guidelines for Stroke Management | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations: Update 2014 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 3 | Stroke in General | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 4 | New Zealand Clinical Guidelines 2010 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5 | National Clinical Guideline for Stroke | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 6 | Vascular Prevention after Stroke or TIA | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 7 | Management of Patients with Stroke or TIA | – | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 8 | Guidelines for the Prevention of Stroke/TIA AHA/ASA | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| 9 | Singapore MOH Clinical Practice Guidelines on Stroke/TIA | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | – |

| 10 | Guidelines for Management of IS/TIA 2008 | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – |

| 11 | Guidelines for the Primary Prevention of Stroke – AHA/ASA | – | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – |

| 12 | New S3 guideline “Stroke-Prevention” of the German Society of Neurology | – | – | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – |

| 13 | Guidelines for Preventive Treatment – Ischemic Stroke and TIA (I)(II) | – | – | – | – | Yes | Yes | – | – |

| 14 | Action Plan, Brain Attack | – | – | Yes | – | – | – | – | – |

| 15 | Guidelines Secondary Prevention Cerebrovascular Disease | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – |

| 16 | Clinical Practice Guidelines Management of Ischemic Stroke | Yes | – | – | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| 17 | Chinese Guidelines for the Secondary Prevention of IS/TIA 2010 | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | – |

| 18 | Clinical Practice Guidelines, Cerebrovascular Disease | – | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – |

| 19 | South African Guideline for Management of IS/TIA 2010 | Yes | – | – | – | Yes | Yes | – | – |

| 20 | Guidelines for Prevention, Treatment & Rehabilitation of Stroke | – | – | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | – |

| 21 | Ischemic Stroke Care – Official Guidelines – Pakistan Society of Neurology | – | – | – | – | Yes | – | Yes | – |

| 22 | Stroke Management | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Best practice guidelines should yield positive evaluation scores for a maximum total score of 8. After rating each guideline according to the IOM system of standards, 5 of 14 HIC guidelines (36%) scored 8 while none from LMICs (p = 0.250), did. Guidelines from 86% of HICs scored at least 4 compared with only 37,5% of those from LMICs (p = 0.250). We did not found significant differences in compliance with the Conflict of Interest standard where 72% of HIC standards had no conflicts. This was true for only 38% in the LMIC (p = 0.187). Systematic reviews met the IOM system of standards in eleven HIC guideline (79%) and 13% for LMIC (p = 0.006). Updating HIC guidelines was specified for 57% and but only in a single LMIC 13% (p = 0.07). We observed a trend for external reviews in HIC 57% and 12% for LMICs (p = 0.07). For the remaining standards of both groups we did not find significant differences between LMICs and HICs, in transparency 55%, multidisciplinary approach 64%, strength of recommendations 91%.

We used different systems for assessing the strength and evidence quality for individual guidelines. We established the type of studies supporting evidence and the task force involved in the guideline development (Table.2) We use some of these assessment systems more frequently than others. In order of usage frequency, the systems were [a] Grading of Recommendations Assessment Development & Evaluation (GRADE) 18% [19] and [b] American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) 22%. The guideline from India did not include an evaluation system because it had not yet been implemented. India plans to incorporate the GRADE system for the next issue of its guideline. In the LMICs, half used the AHA/ASA system. The South African guideline used the AHA/ASA for the appraisal of evidence, but evaluated the recommendations using the European Stroke Organization (ESO) system. Recommendations Class I or Class III Level A or Grade 1 A were supported chiefly from Meta-analysis or systematic reviews of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCT) or well performed RCT.

Table 2.

Quality of studies for high level of evidence, system of graduation and task force.

| N | Country | Support of recommendations | System | Members of Task Force |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Australia | Several Level I or II studies | NHMRC | Physiatrists, pharmacists, neurologists, geriatricians, physiotherapists, rehabilitation, speech pathology, vascular surgeon |

| 2 | Canada | Meta-analysis of RCT or >2RCT | CSBPR | Stroke neurologists, family physicians, internists, nurses, emergency physicians, rehabilitation specialists, pharmacists, stroke survivors, education experts |

| 3 | Japan | 1a meta-analysis, or 1 RCT | NCGS | Stroke neurologists, healthcare professionals, non-stroke physicians |

| 4 | New Zealand | Several Level I studies | NHMRC | Stroke specialist, stroke nurse, economics, general practitioner, stroke physician, neurologist, geriatrician, PT/OT |

| 5 | UK | NS | NICE | Physicians, neurologist, stroke neurologist |

| 6 | France | Grade A (meta-analysis or RCT) | NS | Neurologists, general practitioners, cardiologists, endocrinologists, geriatricians, vascular surgeons, rehabilitation |

| 7 | Scotland | Meta-analysis, systematic review, or RCT | SIGN | Stroke care doctor, pharmacist, speech and language therapist lead stroke nurse consultant vascular surgeonl |

| 8 | US | Level A (multiple RCT or meta-analysis) | AHA/ACC | Cardiology, epidemiology/biostatistics, internal medicine, neurology, nursing, radiology, and surgery |

| 9 | Singapore | Meta-analysis, systematic review, or RCT | SIGN | Neurology, neurosurgery, neuroradiology, rehabilitation, family medicine, nursing, OT, and a lay patient advocate |

| 10 | Europe | Adequate RCT, systematic review of RCT | EFNS | Stroke neurologists |

| 11 | US | Level A (multiple RCT or meta-analysis) | AHA/ASA | Stroke neurologist |

| 12 | Germany | NS | NS | Neurology, stroke neurology |

| 13 | Spain | Systematic review of RCT homogenous | CEBM | Neurologist, stroke neurologists |

| 14 | Chile | NS | NS | Pre-hospital services, public health, neurology, neurosurgery, rehabilitation, emergency medicine |

| 15 | Mexico | ≥1 meta-analysis systematic review or RCT | SIGN | Vascular neurologists, internists, general physicians |

| 16 | Malaysia | ≥1 meta-analysis, systematic review, or RCT | US/CPTF | Neurologists, cardiologist, Neuroradiologist |

| 17 | China | NS | AHA/ASA | Neurology, cardiology, endocrinology, intensive care, respiratory, intervention, and epidemiology |

| 18 | Cuba | Meta-analysis of RCT | AHQRS | Neurology, Intensive care specialist, epidemiology, medicine, primary care physician, geriatrician |

| 19 | South Africa | Requires ≥ 1, Class I or ≥2, Class II studies | ESO | Neurologist, vascular neurologists, geriatricians |

| 20 | Philippines | Data derived from multiple RCT | AHA/ASA | Neurologists, internists, neurosurgeons, vascular surgeons and physiatrists |

| 21 | Pakistan | NS | AHA/ASA | Neurologists |

| 22 | India | NS | NS | NS |

Appendix material includes the following information:

Available Guidelines for Stroke Prevention for 2005–2015 (A-1)

Main Recommendations LOE A, for Primary Stroke Prevention in LMIC (B-1)

Recommendations LOE A, Secondary Stroke Prevention in LMIC (C-1)

Stakeholder Populations (6Ps) Targeted by the Guidelines (D-1)

Translatability, Ethical, Legal, & Socio-economic (ELSE) Considerations (E-1)

Components of the Cardiovascular Quadrangle Addressed (F-1).

4. Discussion

We identified 22 published stroke prevention guidelines dated between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2015. Most of these guidelines were developed in HICs. A previous survey published in 2011 identified 70 stroke guidelines including a variety of different topic areas such as primary and secondary stroke prevention, pre-hospital care, emergency management, inpatient care, and rehabilitation guidelines [2]. After reviewing the guidelines, we observed that most of them followed the continuum of care mentioned above. Some HICs tended to combine primary and secondary stroke prevention in the same document (eg, ESO, Spain). The developing countries (eg, the Philippines, Malaysia, and South Africa, etc.), also treated primary and secondary prevention in the continuum of care guidelines.

The first guidelines were developed in North America in the early 1990s. These early guidelines became models for the world [20]. Our review showed that later guideline development was approximately evenly distributed between Asia, Europe, and North America for HICs. Contrariwise, for non-HICs, 3 guidelines originated in the Philippines, Pakistan, and India. In terms of World Bank economic regions, there was only one guideline from Sub-Sahara Africa (Republic of South Africa) and another single one from Latin America (Mexico).

The guideline development is an expensive, demanding, [2] and continuous [20] process. It requires a multidisciplinary group of experts [21] to spend time and resources [22]. Generating guidelines from the scratch in developing countries is burdensome. LMICs can more efficaciously used their health care resources in more critical areas, such as country-specific studies of prevalence, incidence rates, risk factors, healthcare system limitations, and introduction of minimal standards of care [12]. One strategy proposed by the World Stroke Organization is to adapt high quality clinical practice guidelines from HICs to developing countries [23]. Another strategy is to share systematic reviews and expertise between countries or using public databases such as the Cochrane Library available at no charge to LMICs [2,24]. WHO and World Stroke Organization (WSO) have addressed this issue by developing guidelines and implementation tools for resource-limited countries. General guidelines covering non-communicable diseases such as cancer, asthma, diabetes, and stroke can thereafter be tailored according to differing regional needs [25].

Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) require issuing revised stroke guidelines or updating existing guidelines every 2–3 years [26]. Following these SOPs, we can anticipate obtaining more focused and rigorous guidelines [26]. SOP-compliant guidelines do not necessarily lead to successful implementations [27].

An important implementation barrier is the evidence level upon which individual guidelines are based [28]. Higher quality guidelines facilitate acceptance [29]. As expected, LMICs have less rigorous guidelines compared to HICs. This lack of rigor has a negative impact on implementation and subsequent outcomes. Our primary findings involved the quality of the systematic reviews, articulation of recommendations, external reviewers and guideline updating procedures. Most guideline developers did not specify the standards they used; neither the IOM system of standards nor the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation instrument (AGREE) standards were specified [30].

Today, it is important to comply with modern SOPs in guideline development. In early European studies of guideline, quality pertaining to other chronic conditions (diabetes, hypertension, etc.) showed that the applicability, editorial independence, and stakeholder involvement were the least followed [29]. The introduction of new guidelines requires a fostering environment that involves both patients and physicians in the decision making process [29].

Guideline adoption in developing countries is minimally efficacious in only 50% of LMICs [31]. This low level of efficaciousness explains the “staircase effect” that resulting from limited resources, less reliable diagnostic testing, fewer available competent providers, or poorer patient adherence [31,32]. It is important to involve the stakeholders in the guideline development process [33]. This knowledge translation [31] strengthens the healthcare delivery systems. Translating guidelines into policies and subsequently introducing them in the clinical practice contribute to improving people's health [32].

Different grading systems are used throughout the world – this multiplicity can be confusing. Challenges arise when efforts are expended to adapt, adopt, and combine guidelines. The majority of guidelines examined in this study originated in the United States. Guidelines originating in HICs result in superior AHA/ASA systems. GRADE methodology is most frequently used elsewhere. Canada and several US-based professional associations, eg, American Academy of Neurology (AAN) [34] and American College of Chest Physician (ACCP) [35] are starting to introduce the GRADE system.

The GRADE system has been progressively adopted worldwide. Most of the WHO systematic reviews & Cochrane Reviews are following this system [32,36]. For LICs, the need to create guidelines might forced them to accelerate systematic reviews [32,37]. LMICs find the effort needed to improve their standards to HIC levels is prohibitive [32]. The advantages of using the GRADE system explicitly addressed the quality and strength of evidence [36]. GRADE system methodologies discussed study design, quality, consistency, and directedness based on outcome quality. These guideline methodologies also consider risks, benefits, costs, and applicability in order to strengthen recommendations [38]. GRADE favors translating evidence into practice because it considers different factors (e.g., effect size modifiers, location, and expert resources) [38]. Going forward, we must adopt a new standard of excellence. All new or re-issued guidelines need to include mitigation plans with the means and procedures for monitoring mitigation progress. Often mitigation is completed using review by external organizations such as the Joint Commission of Hospital Accreditation.

During data analysis from LOE (A) recommendations, we found several minor variations among guidelines. We selected the best option for summarizing evidence for each identified risk factor. LMIC guidelines were developed based on statistical evidence obtained in HICs. Now in LMICs more studies are being conducted locally. Among the primary stroke prevention guidelines, two guidelines from Asian countries were included. These guidelines were based on locally generated data. Regarding secondary stroke prevention; studies for hypertension, diabetes, lipid control, anti-coagulants, and anti-platelet were performed in China, South Africa, Mexico, some countries in the Middle East, and South America.

There are concerns about how to translate the evidence into practice and to determine whether a recommendation derived from HIC studies based on specific local populations can be generalized to another, different population having different risk factors [22]. A great pressure has been exerted on LMICs to implement the best evidence-based changes in their own country-specific policies. These policy changes require the development of high quality of systematic reviews following HIC leadership. This partnership has allowed 30+ LMICs to develop systematic reviews [37].

Guidelines were updated periodically in 12 of the 22 countries studied (54%). In fact, all of these 11 countries had issued guidelines prior to 2005. Additionally, guideline schedules were specified in six HIC guidelines (27%) but in only one LMIC guideline (4%). The US primary and secondary ischemic stroke prevention guidelines are reissued every 3 years. In the present study, we were able to identify the update period for only seven countries. The renewal period for these eight countries ranged between 3 and 7 years.

A more extensive search through the Ministry of Health in individual LMICs might well have revealed unpublished guidelines. Thirdly, we evaluated quality using only the IOM standards though other instruments such as AGREE are available. Currently, the most frequently used quality evaluation strategy is the AGREE instrument [30], but the IOM can be used in guideline and recommendation development efforts.

5. Conclusions

The availability of stroke prevention guidelines in LMICs comprises just a third of the total guidelines available in HICs. This disparity may well be a reflection of fewer available LMIC resources. LMIC guidelines typically are limited to brief summaries of complete documents not available in their entirety. One of our recommendations is that HIC journals should promote LMIC guideline publication (Box 1). Research, especially the high-quality ones, in LMICs is quite limited. This scarcity is based on the number of high-quality, local-context LMIC publications. We found that LMIC guidelines are primarily limited to acute stroke treatment. This aspect is profoundly incomplete because mitigation by primary and secondary prevention strategies should be included. Duplicating efforts in LMICs to achieve parity with HIC guidelines is inadvisable.

Box 1. Recommendations to improve the quality of stroke guidelines in LMICs.

- Governmental healthcare policy makers to focus on primary and secondary prevention by allocating resources to the epidemiological studies of non-communicable diseases.

- Local medical associations and Ministries of Health should consider adapting high quality HIC guidelines (ADAPTE Working Group) to their local context [1] or creating partnerships with experts from HICs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

WF is supported by South Carolina Translational Research Discovery Grant [UL1TR001450]; American Heart Association [14SDG1829003]; and National Institute of Health [P2CHD086844]; MO and BO are supported by [U01 NS079179] and [U54 HG007479] from the National Institutes of Health and the GACD. They are members of the GACD Control Unique to Cerebrovascular diseases in Low and Middle Income Countries (GACD-COUNCIL) initiative.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2017.02.040.

References

- 1.Fervers B, Burgers JS, Haugh MC, Latreille J, Mlika-Cabanne N, Paquet L, et al. Adaptation of clinical guidelines: literature review and proposition for a framework and procedure. Int. J. Qual. Health Care. 2006;18(3):167–176. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzi108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindsay MP, Culebras A, Hacke W, Jowi J, Lalor E, Mehndiratta MM, et al. Development and implementation of stroke guidelines: the WSO Guidelines Subcommittee takes the first step (Part one of a two-part series on the work of the WSO Stroke Guidelines Subcommittee) Int. J. Stroke. 2011;6(2):155–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2010.00572.x. Epub 2011/03/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feigin VL, Mensah GA, Norrving B, Murray CJ, Roth GA. Atlas of the Global Burden of Stroke (1990–2013): The GBD 2013 Study. Neuroepidemiology. 2015;45(3):230–6. doi: 10.1159/000441106. Epub 2015/10/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strong K, Mathers C, Bonita R. Preventing stroke: saving lives around the world. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(2):182–7. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(07)70031-5. Epub 2007/01/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;133:e38–e360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feigin VL, Lawes CM, Bennett DA, Barker-Collo SL, Parag V. Worldwide stroke incidence and early case fatality reported in 56 population-based studies: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(4):355–69. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(09)70025-0. Epub 2009/02/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ovbiagele B, Nguyen-Huynh MN. Stroke epidemiology: advancing our understanding of disease mechanism and therapy. Neurotherapeutics. 2011;8(3):319–29. doi: 10.1007/s13311-011-0053-1. Epub 2011/06/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnston SC, Mendis S, Mathers CD. Global variation in stroke burden and mortality: estimates from monitoring, surveillance, and modelling. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(4):345–54. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(09)70023-7. Epub 2009/02/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206–52. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. Epub 2003/12/06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. [accessed June 7, 2016];Cardiovascular Disease: Strategic Priorities 2016. http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/priorities/en/ Available from: http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/priorities/en/

- 11.World Health Organization. [accessed May 20, 2016];Media Centre: Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs) 2016. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en/; http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en/

- 12.Feigin VL, Krishnamurthi R, Bhattacharjee R, Parmar P, Theadom A, Hussein T, et al. New Strategy to Reduce the Global Burden of Stroke. Stroke. 2015;46(00) doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008222. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.115.008222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Stroke Organization. [accessed May 20, 2016];Clinical Practice Guideline 2012. http://www.world-stroke.org/education/clinical-practice-guideline Available from: http://www.world-stroke.org/education/clinical-practice-guideline.

- 14.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. [accessed May 20, 2016];Improving Health and Social Care Through Evidence-based Guidance 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk.

- 15.Open Clinical. [accessed May 20, 2016];Clinical Practice Guidelines 2013. [updated July 08, 2013]. http://www.openclinical.org/guidelines.html Available from: http://www.openclinical.org/guidelines.html.

- 16.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. Epub 2009/07/28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Institute of Medicine. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust 2015. [updated Aug 19, 2015]. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2011/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines-We-Can-Trust/Standards.aspx (accessed May 20; 6)]. Available from: http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2011/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines-We-Can-Trust/Standards.aspx.

- 18.Bennett K, Gorman DA, Duda S, Brouwers M, Szatmari P. Practitioner review: on the trustworthiness of clinical practice guidelines - a systematic review of the quality of methods used to develop guidelines in child and youth mental health. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Schünemann HJ. What is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ Br. Med. J. 2008;336(7651):995–998. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39490.551019.BE. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39490.551019.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shinohara Y. For readers (stroke specialists and general practitioners) of the Japanese guidelines for the management of stroke. Preface. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2011;20(4 Suppl):S1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2011.05.002. Epub 2011/08/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inzitari D, Carlucci G. Italian Stroke Guidelines (SPREAD): evidence and clinical practice. Neurol. Sci. 2006;27(Suppl 3):S225–7. doi: 10.1007/s10072-006-0622-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shekelle PG, Woolf SH, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Developing guidelines. BMJ Br. Med. J. 1999;318(7183):593–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7183.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Stroke Organization. [accessed May 20, 2016];Stroke Guidelines 2012. http://www.world-stroke.org/education/stroke-guideline-development-or-adaptation Available from: http://www.world-stroke.org/education/stroke-guideline-development-or-adaptation.

- 24.Cochrane Library. [accessed June 07, 2016];Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016. [updated 2016; cited Accessed June 07, 2016 June 07, 2016]. http://www.cochranelibrary.com Available from: http://www.cochranelibrary.com.

- 25.World Health Organization. [accessed May 20, 2016];Implementation tools Package of Essential Noncommunicable (PEN) disease interventions for primary health care in low-resource settings 2016. [updated 2016]. http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/publications/implementation_tools_WHO_PEN/en/ Available from: http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/publications/implementation_tools_WHO_PEN/en/

- 26.Ntaios G, Bornstein NM, Caso V, Christensen H, De Keyser J, Diener HC, et al. The European Stroke Organisation Guidelines: a standard operating procedure. Int. J. Stroke. 2015;10(Suppl A100):128–35. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12583. Epub 2015/07/07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCluskey A, Vratsistas-Curto A, Schurr K. Barriers and enablers to implementing multiple stroke guideline recommendations: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013;13:323. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-323. Epub 2013/08/21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baradaran-Seyed Z, Nedjat S, Yazdizadeh B, Nedjat S, Majdzadeh R. Barriers of clinical practice guidelines development and implementation in developing countries: a case study in iran. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2013;4(3):340–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knai C, Brusamento S, Legido-Quigley H, Saliba V, Panteli D, Turk E, et al. Systematic review of the methodological quality of clinical guideline development for the management of chronic disease in Europe. Health Policy. 2012;107(2–3):157–67. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collaboration A. Development and validation of an international appraisal instrument for assessing the quality of clinical practice guidelines: the AGREE project. Qual. Saf. Health care. 2003;12(1):18–23. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.1.18. Epub 2003/02/07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tugwell P, Robinson V, Grimshaw J, Santesso N. Systematic reviews and knowledge translation. Bull. World Health Organ. 2006;84(8):643–51. doi: 10.2471/blt.05.026658. Epub 2006/08/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.English M, Opiyo N. Getting to grips with GRADE-perspective from a low-income setting. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011;64(7):708–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moher D, Weeks L, Ocampo M, Seely D, Sampson M, Altman DG, et al. Describing reporting guidelines for health research: a systematic review. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011;64(7):718–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Culebras A, Messe SR, Chaturvedi S, Kase CS, Gronseth G. Summary of evidence-based guideline update: prevention of stroke in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2014;82(8):716–24. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000000145. Epub 2014/02/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lansberg MG, O'Donnell MJ, Khatri P, Lang ES, Nguyen-Huynh MN, Schwartz NE, et al. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e601S–36S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2302. Epub 2012/02/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):383–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garner P, Kale R, Dickson R, Dans T, Salinas R. Implementing research findings in developing countries. BMJ Br. Med. J. 1998;317(7157):531–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7157.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, Eccles M, Falck-Ytter Y, Flottorp S, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ Br. Med. J. 2004;328(7454):1490. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490. Epub 2004/06/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.