Abstract

Background:

Postoperative bleeding is a common problem in cardiac surgery. We tried to evaluate the effect of topical tranexamic acid (TA) on reducing postoperative bleeding of patients undergoing on-pump coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery.

Materials and Methods:

One hundred and twenty-six isolated primary CABG patients were included in this clinical trial. They were divided blindly into two groups; Group 1, patients receiving 1 g TA diluted in 100 ml normal saline poured into mediastinal cavity before closing the chest and Group 2, patients receiving 100 ml normal saline at the end of operation. First 24 and 48 h chest tube drainage, hemoglobin decrease and packed RBC transfusion needs were compared.

Results:

Both groups were the same in baseline characteristics including gender, age, body mass index, ejection fraction, clamp time, bypass time, and operation length. During the first 24 h postoperatively, mean chest tube drainage in intervention group was 567 ml compared to 564 ml in control group (P = 0.89). Mean total chest tube drainage was 780 ml in intervention group and 715 ml in control group (P = 0.27). There was no significant difference in both mean hemoglobin decrease (P = 0.26) and packed RBC transfusion (P = 0.7). Topical application of 1 g TA diluted in 100 ml normal saline does not reduce postoperative bleeding of isolated on-pump CABG surgery.

Conclusion:

We do not recommend topical usage of 1 g TA diluted in 100 ml normal saline for decreasing blood loss in on-pump CABG patients.

Keywords: Administration, coronary artery bypass, postoperative hemorrhage, topical, tranexamic acid

INTRODUCTION

Diffuse bleeding is a common problem after cardiac operations using cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB). CPB causes platelet dysfunction, decreased clotting factors, and fibrinolysis.[1,2,3] Significant fibrinolysis after CPB is reflected by increased concentrations of plasmin and fibrin degradation products.[4] Nearly 2%–6% of patients need re-exploration for excessive mediastinal bleeding after coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery[5,6,7] which is responsible for 10.3% of all CABG surgery deaths. Almost 25%–40% of significant postbypass bleedings are caused by fibrinolysis.[8] There are several antifibrinolytic drugs such as aminocaproic acid,[9] aprotinin,[10] and tranexamic acid (TA).[11,12,13,14] Their systemic usage has been shown to reduce postbypass bleeding but may be associated with thromboembolic complications and early graft closure.[15,16,17] There are some different reports of topical TA usage for reduction of postbypass bleeding.[18,19,20] We tried to include a larger number of patients to evaluate topical TA effect on postoperative bleeding of on-pump CABG patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This study was randomized and double-blinded clinical trial; questionnaires were filled by different personnel in intensive care unit (ICU) and operating room, and the surgeon was not aware of it. Patients who received TA therapy (intervention group) were compared to patients who used normal saline therapy (control group). Inclusion criteria were patients undergoing CABG surgery alone, interrupting aspirin 3 days[18] and Plavix at least 5 days before surgery, lack of consuming any other anticoagulant drugs such as heparin or warfarin, lack of coagulation and bleeding disorders, and lack of liver and kidney disease.[20] Exclusion criteria were complex surgery, emergency surgery, anticoagulation therapy before surgery, and having hemoglobin lower than 8 g per deciliter before surgery. Written consent form was obtained from patients. This study was registered with IRCT2016071628945N1q number.

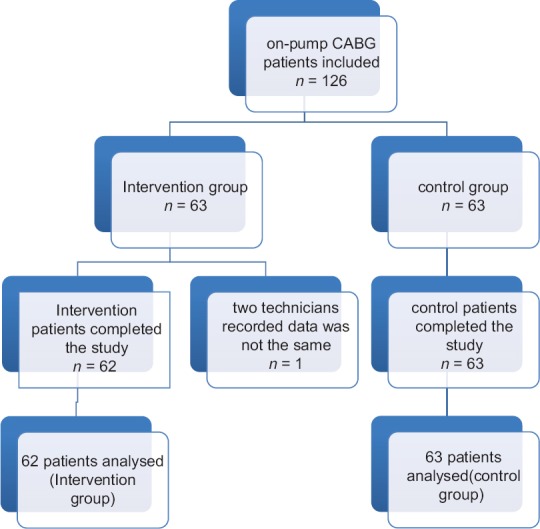

One hundred and twenty-six patients undergone CABG, who had been diagnosed by a cardiologist and based on inclusion and exclusion criteria were included in the study. The patients were divided into two groups of intervention and control (63 cases in control group and 63 cases in intervention group). One hundred and twenty-five patients completed the study; 62 from TA group and 63 from normal saline group. Random assignment was performed by dividing patients into even and odd year of birth; even years were intervention group and odd years were control group [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Patient enrollment flowchart

The anesthetic management and conduct of CPB were standardized. The patients were premedicated using nitrazepam 0.1 mg/kg tablet the night of the operation and morphine 0.15 mg/kg intramuscular ½ h before operation. Induction was done using fentanyl 2–5 ug/kg, propofol 1–2 mg/kg, and pancuronium 0.1 mg/kg. Anesthesia was maintained using sevoflurane 0.5%–1%, pancuronium 0.06 mg/kg, and fentanyl 1–2 ug/kg during CPB time. All patients received heparin 300 units/kg before CPB to achieve target activated clotting time (ACT) of ≥480 s. During CPB, extra heparin was given as needed to maintain the target ACT.[20]

After completion of the operation and suction all fluids and blood in the wound, for intervention group, TA (TRANEXIP, Capiantamin Company) with dose of 1 g diluted in 100 mL of saline, and for the control group, 100 mL of saline was poured into pericardial space and then the chest tube was clamped and the wound was closed and the patient was transferred to the ICU and then chest tubes were opened. The primary outcome measure for our study was the 1st day bleeding amount in the chest bottle, total amount of bleeding in 48 h, and the amount of blood transfusion. Two different technicians collecting the same data separately and the surgeon were not informed about the groups.

Statistical analysis

Analysis was done using descriptive statistics such as mean and standard deviation and analytical statistics such as t-test, Mann–Whitney test, and Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficient by SPSS software version 22. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

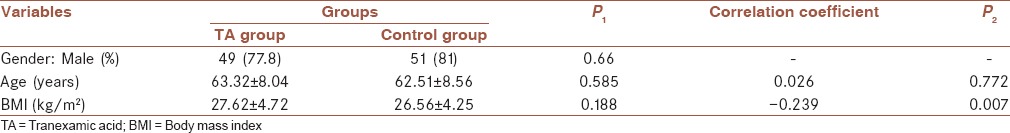

Both groups were matched in terms of age (P = 0.585) and gender (P = 0.66) [Table 1]. One patient was dropped out and finally, 125 patients completed the study. The age range of patients in the intervention group was 41–79 years and control group 40–78 years. In intervention group, 77.8% (n = 49) of patients were male and in control group was 81% (n = 51). Moreover, serious adverse event were not observed in both groups.

Table 1.

Demographic data of the study sample

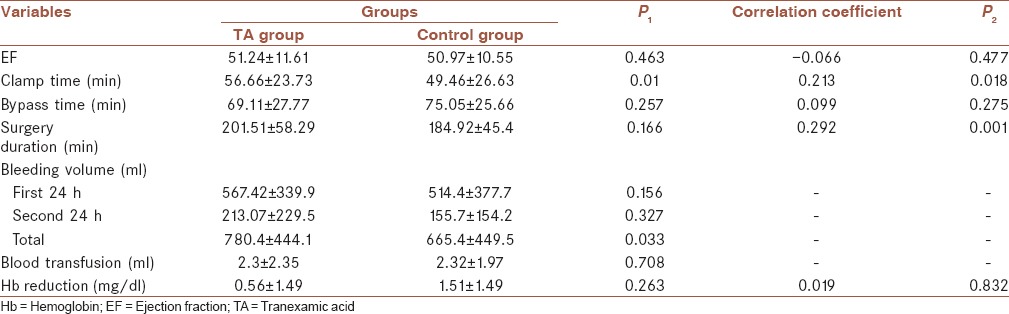

Furthermore, body mass index (BMI) and ejection fraction [Tables 1 and 2] did not show a significant differences between the groups (P = 0.188 and P = 0.463, respectively). As obtained, clamp time was significantly more in intervention group as compared to control group (56.66 vs. 49.46 min) (P = 0.01). Surgery duration and bypass time in both groups were same to each other and no differences were obtained (P = 0.257 and P = 0.166, respectively).

Table 2.

Results of the study sample

In Table 2, it is shown that the mean of bleeding amount in first 24 h after surgery in intervention group was 567.42 ml and in control group was 564.44 ml (P = 0.894). Moreover, the mean of bleeding amount in second 24 h after surgery and totally in intervention group was 213.07 ml and 780.48 ml, respectively, and in control group was 155.71 ml and 665.4 ml, respectively (P = 0.327 and P = 0.033, respectively); it shows that the amount of bleeding had no statistically difference in both groups. Furthermore, the mean of blood transfusion and hemoglobin decreasing did not show a significant correlation between the groups (P = 0.708 and P = 0.263, respectively).

As obtained, the risk factors for massive bleeding in patients undergoing CABG surgery were BMI (correlation coefficient = −0.239, P = 0.007), clamp time (correlation coefficient = 0.213, P = 0.018), and surgery duration (correlation coefficient = 0.292, P = 0.001), which shows that BMI had reverse correlation with bleeding volume, whereas clamp time and surgery duration had positive and significant correlation with bleeding volume.

DISCUSSION

Intravenous use of TA has proved to be effective in decreasing postoperative bleeding of CABG surgery.[11,21,22] On the other hand, Ovrum et al. have shown no significant decrease in blood loss with intravenous TA usage and also have shown possible increased risk of thromboembolic complications including graft closure with antifibrinolytic usage after CABG.[15] The concept of using topical usage of antifibrinolytic agents was studied in several trials to prevent possible thromboembolic complications of their intravenous usage and has published decreased postoperative bleeding with topical usage of TA.[18,20] Bonis et al. poured 1 g TA in 100 mL of saline solution in mediastinal cavity of twenty patients and compared them with twenty control patients and showed significant reduction in postoperative bleeding.[18] Fawzy et al. compared 19 patients receiving 1 g TA diluted in 100 ml normal saline with 19 control group patients and resulted in significant reduction in postoperative blood loss without adding extra risk to the patients.[20] In our study, larger numbers of patients (125 patients) were included and the effectiveness of topical usage of 1 g TA diluted in 100 ml normal saline in preventing post-CABG blood loss was assessed. The amount and concentration of TA used in our study were nearly similar to other studies. The study showed no difference in postoperative blood loss in either first or second 24 h. Furthermore, blood transfusion was not decreased in the study group.

CONCLUSION

We do not recommend topical usage of 1 g TA diluted in 100 ml normal saline for decreasing blood loss in on-pump CABG patients. More studies are needed to clear why there are different results of different studies. Furthermore, it is recommended to apply larger amounts of local TA to assess its effectiveness in decreasing postoperative blood loss.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Islamic Azad University Najafabad Branch, Isfahan, Iran.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the dedicated efforts of Mrs. Najimeh Tarkesh Esfahani, M. Sc of biostatistics, the volunteer patients who participated in this study, and the Clinical Research Development Unit of Isfahan Sina hospital.

REFERENCES

- 1.Despotis GJ, Santoro SA, Spitznagel E, Kater KM, Cox JL, Barnes P, et al. Prospective evaluation and clinical utility of on-site monitoring of coagulation in patients undergoing cardiac operation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;107:271–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rinder CS, Mathew JP, Rinder HM, Bonan J, Ault KA, Smith BR, et al. Modulation of platelet surface adhesion receptors during cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesthesiology. 1991;75:563–70. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199110000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kucuk O, Kwaan HC, Frederickson J, Wade L, Green D. Increased fibrinolytic activity in patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass operation. Am J Hematol. 1986;23:223–9. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830230306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemmer JH, Jr, Stanford W, Bonney SL, Breen JF, Chomka EV, Eldredge WJ, et al. Aprotinin for coronary bypass operations: Efficacy, safety, and influence on early saphenous vein graft patency. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;107:543–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dacey LJ, Munoz JJ, Baribeau YR, Johnson ER, Lahey SJ, Leavitt BJ, et al. Reexploration for hemorrhage following coronary artery bypass grafting: Incidence and risk factors. Northern New England cardiovascular disease study group. Arch Surg. 1998;133:442–7. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.133.4.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sellman M, Intonti MA, Ivert T. Reoperations for bleeding after coronary artery bypass procedures during 25 years. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1997;11:521–7. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(96)01111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehta RH, Sheng S, O’Brien SM, Grover FL, Gammie JS, Ferguson TB, et al. Reoperation for bleeding in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery: Incidence, risk factors, time trends, and outcomes. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:583–90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.858811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kevy SV, Glickman RM, Bernhard WF, Diamond LK, Gross RE. The pathogenesis and control of the hemorrhagic defect in open heart surgery. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1966;123:313–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daily PO, Lamphere JA, Dembitsky WP, Adamson RM, Dans NF. Effect of prophylactic epsilon-aminocaproic acid on blood loss and transfusion requirements in patients undergoing first-time coronary artery bypass grafting. A randomized, prospective, double-blind study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;108:99–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cosgrove DM, 3rd, Heric B, Lytle BW, Taylor PC, Novoa R, Golding LA, et al. Aprotinin therapy for reoperative myocardial revascularization: A placebo-controlled study. Ann Thorac Surg. 1992;54:1031–6. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(92)90066-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horrow JC, Hlavacek J, Strong MD, Collier W, Brodsky I, Goldman SM, et al. Prophylactic tranexamic acid decreases bleeding after cardiac operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1990;99:70–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casati V, Bellotti F, Gerli C, Franco A, Oppizzi M, Cossolini M, et al. Tranexamic acid administration after cardiac surgery: A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Anesthesiology. 2001;94:8–14. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200101000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casati V, Guzzon D, Oppizzi M, Bellotti F, Franco A, Gerli C, et al. Tranexamic acid compared with high-dose aprotinin in primary elective heart operations: Effects on perioperative bleeding and allogeneic transfusions. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;120:520–7. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2000.108016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levi M, Cromheecke ME, de Jonge E, Prins MH, de Mol BJ, Briët E, et al. Pharmacological strategies to decrease excessive blood loss in cardiac surgery: A meta-analysis of clinically relevant endpoints. Lancet. 1999;354:1940–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01264-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ovrum E, Am Holen E, Abdelnoor M, Oystese R, Ringdal ML. Tranexamic acid (Cyklokapron) is not necessary to reduce blood loss after coronary artery bypass operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1993;105:78–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sabzi F, Moradi GR, Dadkhah H, Poormotaabed A, Dabiri S. Low dose aprotinin increases mortality and morbidity in coronary artery bypass surgery(*) J Res Med Sci. 2012;17:74–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aghadavoudi O. Low dose aprotinin increases mortality and morbidity in coronary artery bypass surgery. J Res Med Sci. 2012;17:313. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Bonis M, Cavaliere F, Alessandrini F, Lapenna E, Santarelli F, Moscato U, et al. Topical use of tranexamic acid in coronary artery bypass operations: A double-blind, prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;119:575–80. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(00)70139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pleym H, Stenseth R, Wahba A, Bjella L, Karevold A, Dale O, et al. Single-dose tranexamic acid reduces postoperative bleeding after coronary surgery in patients treated with aspirin until surgery. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:923–8. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000054001.37346.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fawzy H, Elmistekawy E, Bonneau D, Latter D, Errett L. Can local application of tranexamic acid reduce post-coronary bypass surgery blood loss? A randomized controlled trial. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;4:25. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-4-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karski JM, Teasdale SJ, Norman PH, Carroll JA, Weisel RD, Glynn MF, et al. Prevention of postbypass bleeding with tranexamic acid and epsilon-aminocaproic acid. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1993;7:431–5. doi: 10.1016/1053-0770(93)90165-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rousou JA, Engelman RM, Flack JE, 3rd, Deaton DW, Owen SG. Tranexamic acid significantly reduces blood loss associated with coronary revascularization. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;59:671–5. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(94)01010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]