Abstract

Aim:

The aim of the present study was to assess the periodontal condition and sensitivity of second mandibular molars after the extraction of the adjacent third molar, while also assessing the quality of life of the patients.

Materials and Methods:

Twenty-three healthy patients were assessed in terms of probing depth, gingival height, gingival thickness, dental sensitivity, plaque index and bleeding on probing (adjacent second mandibular molar), before the surgical procedure, as well as 60 and 180 days after the surgery. The following data were also recorded and measured: the position and size of the impacted teeth; the size of the alveoli after surgery and the quality of life of the patient.

Results:

Significant differences were found for probing depth and gingival height before and after 180 days. The plaque index increased significantly after surgery (P = 0.004), as did bleeding on probing. No significant difference was found for the quality of life. The size of the third molar extracted was correlated with bleeding on probing 180 days after the surgery.

Conclusion:

An improvement was noted in the periodontal condition of the second mandibular molars after the extraction, based on the assessments of probing depth and gingival height. The position of the third molar affected the periodontal condition of the second mandibular molar. No alterations were recorded for dental sensitivity or the quality of life after the extraction.

Keywords: Oral surgery, periodontal status, second molar, third molar, tooth impacted

INTRODUCTION

Impacted third molars (3M), as well as other teeth in the same condition, may predispose an individual to other problems, such as pericoronitis,[1,2] orofacial infections,[3] dental caries,[4] periodontitis,[5] resorption of the adjacent tooth, cystic or neoplastic alterations, orthodontic or prosthetic problems, and even temporomandibular joint disorder.[6,7,8] These diseases can lead to certain symptoms that seriously affect the patients quality of life.[1,2,6,9,10]

Periodontal disease and the condition of the gum around the second and third molars has been studied for many years to determine the impact of the presence of third molars on the periodontal condition of second molars.[11] The previous studies have shown that completely erupted second molars (2M) that are in close proximity to an impacted 3M exhibit a greater prevalence of periodontal disease.[5,12] Another study reported an increase in gingival plaque due to the presence of an impacted 3M in the hemiarch, as well as the relative difficulty in maintaining good oral hygiene in the posterior areas of the arch.[13] The accumulation of plaque can lead to the development of periodontal disease and apical migration of the periodontal ligament in the distal root of the 2M.[14]

The pattern of mesioangular impaction of the 3M favors the colonization of the subgingival microbiota, due to the difficulties associated with hygiene, and leads to the appearance of a periodontal pocket in the distal region of the 2M, causing a loss of bone support between the two teeth.[15] In these cases, surgical removal of the 3M may cause a periodontal defect on the distal surface of the adjacent 2M, which is more obvious in the case of third molars that are completely or partially impacted than in completely erupted teeth.[14,16] Thus, the studies have suggested that the periodontal condition of second molars can be influenced by the position of impacted third molars.

The literature suggests that the impaction of a 3M, as well as mesioangular and horizontal positions, could predispose individuals to develop periodontal diseases in the region between the second and third molars. However, it is still not clear if the periodontal condition of the 2M improves after the removal of the adjacent 3M, or if this type of procedure could lead to greater periodontal destruction. Moreover, a recent meta-analysis suggested further researches on variations of surgical 3M removal techniques based on periodontal care M2M.[11] In addition, this seems to be the first study that assessed the sensitivity of the 2M after the extraction of a 3M.

The aim of the present prospective study was to assess the periodontal condition and sensitivity of the mandibular 2Ms of patients submitted to the extraction of the adjacent 3M, by comparing the positioning of the 3M and the periodontal status of the adjacent 2M, as well as to determine the impact on the quality of life of these patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample

The sample size was calculated considering the standard deviation of probing depth as 0.26 mm.[14] The difference to be detected before and after treatment was stipulated as 0.44 mm, with a level of significance of 95% and power of 80%. On adding 10% to the value found (to prevent possible losses), a total of 23 mandibular 2Ms, with their adjacent 3Ms.

The procedures were carried out on patients who had been indicated for the extraction of an impacted or semi-impacted lower 3M and the adjacent 2M was present, they did not present periodontitis. All of the participants were at least 18-year-old and signed an informed statement of consent before the start of this research. This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Jequitinhonha and Mucuri Valleys, in which the work was performed (protocol number 12943713.7.0000.5108). The present study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, revised in 2013.

Assessment and monitoring

All of the patients underwent a clinical examination, in which the periodontal condition of the relevant teeth was determined. With regards to the 2M, the following parameters were assessed: (1) measurement of the probing depth using a manual Williams periodontal probe (Williams probe, Golgran, São Paulo, Brazil) and an electronic probe (Florida probe system, Gainesville, FL 32606, USA), considering the highest value of all faces of the 2M; (2) the height of the keratinized gingiva, using the Williams periodontal probe to measure the vestibular face of the 2M; (3) keratinized gingival thickness on the vestibular face of the 2M, assessed by a digital endodontic spacer (Maillefer, Dentsply, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) and an endodontic ruler (Odous De Deus, Dentsply, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil); (4) dental sensitivity was measured by thermal (Endo-Ice, Maquira, Paraná, Brazil) and evaporative tests (air jet) (5) bleeding during probing; and (6) and the plaque index,[17] in the entire oral cavity.

Periapical radiographs were used to assess the positions of the impacted mandibular 3Ms in relation to the occlusal plane and the anterior mandibular ramus, as per the Pell and Gregory classification.[18] For these radiographs, the distance between the occlusal plane and the root apex of the third molars was measured using an endodontic millimeter ruler.

The alveolar size of the alveolar bone crest level (apex) was measured trans-surgically using a Williams periodontal probe (Williams probe, Golgran, São Paulo, Brazil), which was placed inside the alveoli to perform the measurement. The effect of oral health on the general well-being of the patient was determined using a questionnaire that assessed the quality of life in relation to oral health (14-item Oral Health Impact Profile [OHIP-14]).[19] The OHIP-14 scores range from 0 to 56 points, with higher scores representing a greater impact on the quality of life.

All parameters were assessed by a single calibrated and trained examiner (LEOM) at baseline (T1), before the surgery, and 60 (T2) and 180 (T3) days after the surgery. To confirm the reliability of the measurements taken by the examiner (LEOM), the gingival height, gingival thickness, and probing depth of all faces of the right mandibular 2M were measured in eight patients. After 60 days, the measurements were taken once again, using the same patients and the same locations. The intraclass correlation coefficient test was used to confirm the reproducibility of the results, with a result of 0.968, using the probing depth. The patients assessed in the calibration were not included in the present study.

Surgical procedure

All surgical procedures were performed by the same surgeon, who was an experienced specialist in oral and maxillofacial surgery. The surgical technique used was similar to that described by Leonard in 1992.[20] In brief, local anesthesia was carried out using lidocaine in a solution of 2%, with epinephrine at 1:100.000 (Alphacaine 100, DFL, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). After incision with a number 15 scalpel blade, the soft tissue was displaced to expose the surgical area. Subsequently, the soft tissue was withdrawn and when necessary, low-speed osteotomy was conducted with spherical burs (number 6), mounted on a handpiece device (30,000 rpm). High-speed odontosection was also performed when necessary (350,000 rpm), using a carbide bur 702c (SS White, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) mounted on a high-speed turbine. The osteotomy and odontosection procedures were performed under constant irrigation with sterile sodium chloride solution (0.9%). The extraction was then performed using Seldin elevators and/or curved elevators, careful curettage, bone regularization and surgical cleansing, with abundant irrigation. The suture was conducted using silk yarn (4.0) and isolated points. The suture was removed after 7 days.

Anti-inflammatories (ibuprofen 600 mg every 8 hours for 3 days) and painkillers (paracetamol 750 mg every 8 h for 3 days, if pain is present) were prescribed. All postoperative instructions were explained by the surgeon and printed in a report which was given to the patients.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS 22.0 for Windows software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). The variables were submitted to descriptive analysis of the data. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to confirm the normality of the data distribution, which was abnormal for the variables. Friedman's test was used to assess the alteration of the periodontal profiles of the distal surfaces at T1, T2, and T3 for the variables analyzed, with Wilcoxon's post hoc test. For the variable quality of life, the analysis was performed between T1 and T3 using the Wilcoxon's test. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to determine the influence of the variables related to the mandibular 3M on the periodontal status of the mandibular 2M, with the Mann–Whitney post hoc test. Spearman's correlation was determined to confirm associations between the size of the alveoli immediately after the extraction and the periodontal variables.

RESULTS

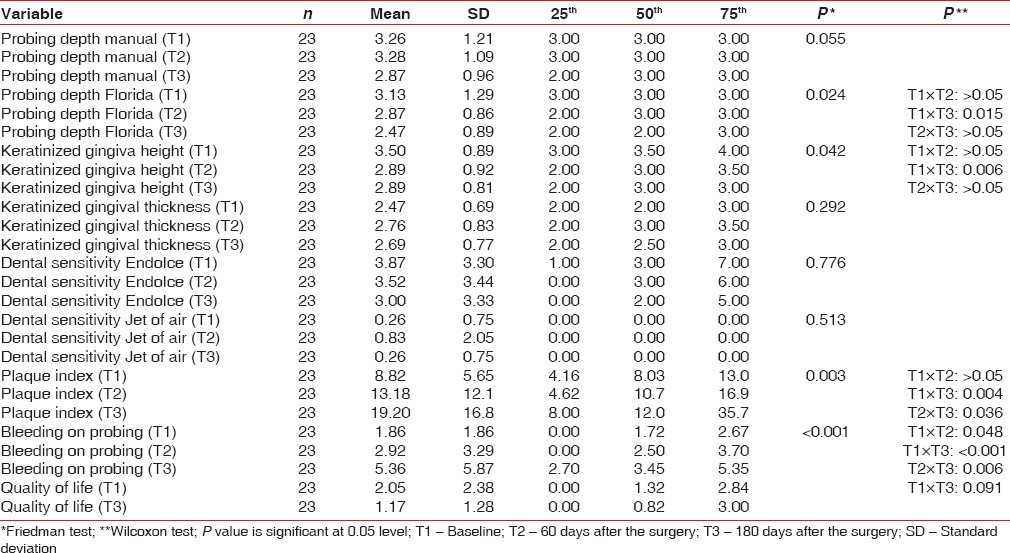

All patients who started T1 continued until T3, 19 females and 4 males with a mean age of 20.38 years. Therefore, no losses were recorded during the present study. There were no complications after the third molar mandibular surgical removal. Most of the 3Ms involved were Class III (n = 10, 43.2%) and type B (n = 10, 43.5%). Table 1 displays the results of the periodontal assessment before and after the extraction of the mandibular 3Ms. Significant differences were recorded for the following variables: probing depth; keratinized gingival height; plaque index; and bleeding during probing in the three time periods assessed.

Table 1.

Status of the mandibular second molar before and after removing the adjacent third molar

A significant decrease in probing depth was recorded between T1 and T3 (P = 0.015). A similar result was also found for gingival height (P = 0.006). With regards to the plaque index, a significant increase was recorded after the extraction (P = 0.004). There was a significant increase in bleeding during probing between T1 and T3 (P = 0.048), between T1 and T2 (P < 0.001), and between T2 and T3 (P = 0.006) [Table 1].

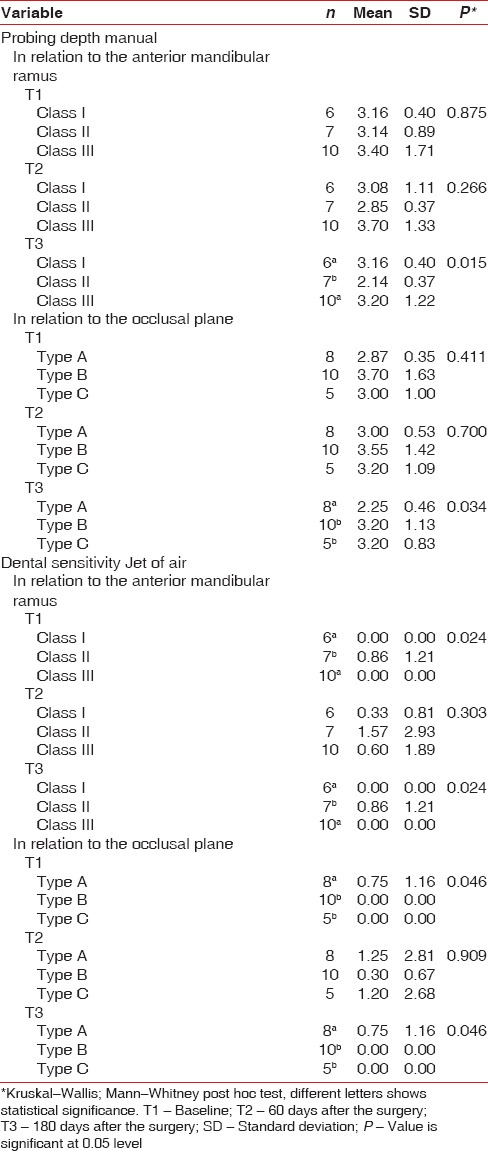

No significant difference was recorded for the effect of oral status on the quality of life 180 days after the extraction [Table 1]. No differences were found between the probing depth with a manual probe (2Ms) and the classification of the position of the 3Ms at T1 and T2 [Table 2].

Table 2.

Modification of the second molar periodontal profile in relation to the adjacent third molar position

However, at T3, it was notable that the 2Ms with adjacent class II and type A 3Ms exhibited a lower mean probing depth than the others. With regards to the dental sensitivity at T1 and T3, it was notable that the 2Ms with adjacent Class II and type A 3Ms exhibited a greater mean sensitivity than the others [Table 2].

No correlation was found between the size of the alveoli after the extraction and the periodontal parameters. The size of the extracted 3Ms exhibited a moderate positive correlation (r = 0.462; P = 0.027) with bleeding on probing after 180 days of surgery.

DISCUSSION

The present study investigated the periodontal condition of mandibular 2Ms, making comparisons before the extraction, as well as 60, 180 days after the extraction, of enclosed or semi-enclosed adjacent 3Ms. A previous study reported that an increase in the periodontal pocket is not common after the extraction of a 3M,[21] which is similar to the results of the present study. Another study demonstrated that there was an improvement in the probing depth on the distal surface of the 2Ms after the extraction of the adjacent 3M.[22] This result was similar to those found in the present study, in which a significant reduction in probing depth was recorded for the 2M 180 days after the surgery (P = 0.015). The assessment of the manual probe confirmed a decrease in probing depth between T1 and T3, although the difference was not statistically significant. It could be suggested that the sensitivity of the Florida probe affected the results, given that the manual probe provided a P value of approximately 0.05. A number of authors have reported that the presence of food particles in areas that are difficult to clean, such as between impacted mandibular 2Ms and 3Ms, can lead to inflammation and alterations in the gingival tissue around the third molar and the sextant.[5,23] This could explain the improvement in the probing depth after the extraction of the 3M.

Two previous studies[24,25] assessed the probing depth, gingival insertion, and gingival height of the distal surfaces of 2Ms after the extraction of the adjacent 3M. No significant results were recorded in these studies, unlike the present study, in which we recorded a decrease in the probing depth and a significant decrease in the gingival height of the 2M 6 months after the surgery. These different results could be explained by the distinct assessment methods used in the three studies.[14] However, a number of authors have previously reported that the extraction of 3Ms can lead to alterations in the periodontal condition of 2Ms, particularly on the distal surface.[24,25]

Krausz et al.[14] assessed the presence of plaque on the distal surface of 2Ms 28 months after the extraction of 3Ms. The authors found a significant decrease in the plaque index when compared with the control group, in which the 3M was not extracted. Different results were reported in another study, which found no significant differences for the plaque inde × 12 months after extracting a 3M.[26] In the present study, the plaque index was assessed in the entire oral cavity, providing results that differed to the previous studies, including a significant increase 6 months after the extraction of the 3M. This result was not expected. This could also explain the significant increase in bleeding on probing, which was also assessed in the entire oral cavity, 2 months and 6 months after the surgery. These results are contrary to those reported by Sammartino et al.[27] who reported no significant differences between the baseline and postoperative assessments, although they are similar to the results reported by Kan et al.[21] even when only assessing the distal surfaces of the 2Ms, with no significant difference in bleeding during probing. The results of the present study confirmed that the larger the tooth extracted, the greater the chances of bleeding around the 2M during probing (Florida probe) 6 months after the surgery.

It has previously been hypothesized that the type of flap used during the extraction of the 3M effects the periodontal condition of the adjacent 2M after surgery. However, several studies have compared different types of flaps in relation to the extraction of a 3M and concluded that the periodontal tissue of the 2M was not significantly different after the extraction of the 3M.[28,29,30] Thus, it is believed that the surgical technique applied in the present study (envelope flap) did not affect the results obtained. Nevertheless, further studies comparing the periodontal condition of different types of flaps are necessary.

The effect of oral health on the quality of life of patients before and after surgery was also addressed in the present study, based on the application of the OHIP-14. No alterations were found after the removal of the 3M. Another study that used this same tool reported that patients exhibited a significant decrease in their OHIP-14 score after the extraction of impacted 3Ms.[30] In other words, oral health had less of an impact on their quality of life 3 months after the surgery. An even more significant improval in the quality of life was recorded 6 months after the treatment. However, in the present study, the OHIP-14 score decreased after 6 months, although this decrease was not statistically significant. This may have been caused by the different populations selected for each study. In a study by McGrath et al.,[31] patients with the previous experience of pericoronitis exhibited a significantly greater decrease in the OHIP-14 score than patients with no such experience. Another two studies also assessed the quality of life of patients after the extraction of a 3M, both of which involved patients with mild pericoronitis symptoms. The results confirmed a significant improval in the quality of life of patients after surgery in both studies.[1,2] The present study included patients with orthodontic indications, without painful symptoms or a history of pericoronitis, which could explain the difference between the results found.

The periodontal conditions of the 2Ms assessed in the present study were also compared with the position of the 3M, considering the Pell and Gregory classification.[18] The probing depth of the 2M, assessed by a manual probe, was lower 180 days after the surgery when the adjacent 3M belonged to class II. The measurements of the periodontal pocket were also lower when the adjacent 3M was type A, confirming that second molars with adjacent third molars of class II or type A are less likely to exhibit an increased probing depth 6 months after extracting the 3M. One possible explanation for this is that the position of the 3M in class II and type A could lead to better postoperative healing, given that it is located just below a gingival layer and in front of the mandibular ramus. Thus, there is no need for a long flap, which could cause the loss of keratinized gingival tissue. However, it was also confirmed that 2Ms are more sensitive to the triple syringe when the 3M is type A and class II, both before the surgery and 180 days after the procedure. Further clinical studies are required to provide concrete evidence of these results. There are no such studies in the literature at present.

The third molars where present, they can cause damage periodontal condition of the mandibular 2Ms.[1,2,5,13,15] This research suggests that the extraction of third molars improve the periodontal status of adjacent second molar. Dentists should make radiographs of third molars frequently to verify level of the third molar relation with the second molar because some angulation positions are more unfavorable for the maintenance of periodontal health and these cases should be indicated for extraction.

Although well delineated, the present study may contain a number of limitations. For instance, dentin sensitivity was assessed by Endo-Ice, which is a rigorous vitality test, although ice water should be used as a congenital diaphragmatic hernia stimulus. The absence of a control group for the comparison of results could also be considered a limitation of this research. Furthermore, the absence of clinical attachment level measurement may limit the results and discussion, since the probing depth can over- or under-estimated the level of bone support. Prospective studies with representative samples are necessary to corroborate or refute the results of the present study.

The periodontal condition on the distal surface of 2Ms improved after the extraction of the 3M, in terms of the probing depth. The position of the 3M before the extraction affected the periodontal condition of the 2M after extraction, particularly when the 3M was class II or type A. There is no impact of the 3M on quality of life or 2M sensitivity.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was financially supported by Foundation for Research Support of the State of Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG, Minas Gerais, Brazil) and Higher Education Personnel Improvement Coordination (CAPES, Brazil).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the Foundation for Research Support of the State of Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG, Minas Gerais, Brazil) and Higher Education Personnel Improvement Coordination (CAPES, Brazil) for the financial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tang DT, Phillips C, Proffit WR, Koroluk LD, White RP., Jr Effect of quality of life measures on the decision to remove third molars in subjects with mild pericoronitis symptoms. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;72:1235–43. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Magraw CB, Golden B, Phillips C, Tang DT, Munson J, Nelson BP, et al. Pain with pericoronitis affects quality of life. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.06.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenstein A, Witherspoon R, Leinkram D, Malandreni M. An unusual case of a brain abscess arising from an odontogenic infection. Aust Dent J. 2015;60:532–5. doi: 10.1111/adj.12266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falci SG, de Castro CR, Santos RC, de Souza Lima LD, Ramos-Jorge ML, Botelho AM, et al. Association between the presence of a partially erupted mandibular third molar and the existence of caries in the distal of the second molars. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41:1270–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blakey GH, Jacks MT, Offenbacher S, Nance PE, Phillips C, Haug RH, et al. Progression of periodontal disease in the second/third molar region in subjects with asymptomatic third molars. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:189–93. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adeyemo WL. Do pathologies associated with impacted lower third molars justify prophylactic removal? A critical review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102:448–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akarslan ZZ, Akdevelioǧlu M, Güngör K, Erten H. A comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of bitewing, periapical, unfiltered and filtered digital panoramic images for approximal caries detection in posterior teeth. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2008;37:458–63. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/84698143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Khateeb TH, Bataineh AB. Pathology associated with impacted mandibular third molars in a group of jordanians. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:1598–602. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.11.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.John MT. Oral health-related quality of life is often poor among patients seeking third molar surgery. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2005;5:158–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McNutt M, Partrick M, Shugars DA, Phillips C, White RP., Jr Impact of symptomatic pericoronitis on health-related quality of life. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:2482–7. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barbato L, Kalemaj Z, Buti J, Baccini M, La Marca M, Duvina M, et al. Effect of surgical intervention for removal of mandibular third molar on periodontal healing of adjacent mandibular second molar: A Systematic review and bayesian network meta-analysis. J Periodontol. 2016;87:291–302. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.150363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodsell JF. An overview of the third molar problem. Quintessence Int Dent Dig. 1977;8:11–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ylipaavalniemi P, Turtola L, Rytömaa I, Helminen S, Jauhiainen L. Effect of position of wisdom teeth on the visible plaque index and gingival bleeding index. Proc Finn Dent Soc. 1982;78:47–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krausz AA, Machtei EE, Peled M. Effects of lower third molar extraction on attachment level and alveolar bone height of the adjacent second molar. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;34:756–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leung WK, Corbet EF, Kan KW, Lo EC, Liu JK. A regimen of systematic periodontal care after removal of impacted mandibular third molars manages periodontal pockets associated with the mandibular second molars. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:725–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lobera-Prado K, Vallcorba-Plana N, Uribarri-Echevarría A, Sanahuja-Figueras C, Gay-Escoda C. Niveles de inserción em distal del segundo molar después de la extracción del tercer molar inferior. Rev Eur Odontoestomatol. 2003;15:129–136. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Löe H. The gingival index, the plaque index and the retention index systems. J Periodontol. 1967;38(Suppl):610–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1967.38.6.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pell GJ, Gregory BT. Impacted mandibular third molars: Classification and modified techniques for removal. Dent Dig. 1933;39:330–338. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slade GD. Derivation and validation of a short-form oral health impact profile. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997;25:284–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1997.tb00941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leonard MS. Removing third molars: A review for the general practitioner. J Am Dent Assoc. 1992;123:77–8. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1992.0041. 81-2, 85-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kan KW, Liu JK, Lo EC, Corbet EF, Leung WK. Residual periodontal defects distal to the mandibular second molar 6-36 months after impacted third molar extraction. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:1004–11. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.291105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montero J, Mazzaglia G. Effect of removing an impacted mandibular third molar on the periodontal status of the mandibular second molar. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:2691–7. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.06.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White RP, Jr, Offenbacher S, Blakey GH, Haug RH, Jacks MT, Nance PE, et al. Chronic oral inflammation and the progression of periodontal pathology in the third molar region. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:880–5. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ziegler RS. Preventive dentistry – New concepts. Preventing periodontal pockets. Va Dent J. 1975;52:11–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kugelberg CF. Periodontal healing two and four years after impacted lower third molar surgery. A comparative retrospective study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;19:341–5. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(05)80077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirtiloǧlu T, Bulut E, Sümer M, Cengiz I. Comparison of 2 flap designs in the periodontal healing of second molars after fully impacted mandibular third molar extractions. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:2206–10. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sammartino G, Tia M, Bucci T, Wang HL. Prevention of mandibular third molar extraction-associated periodontal defects: A comparative study. J Periodontol. 2009;80:389–96. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaves AJ, Nascimento LR, Costa ME, Franz-Montan M, Oliveira-Júnior PA, Groppo FC, et al. Effects of surgical removal of mandibular third molar on the periodontium of the second molar. Int J Dent Hyg. 2008;6:123–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2008.00297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sandhu A, Sandhu S, Kaur T. Comparison of two different flap designs in the surgical removal of bilateral impacted mandibular third molars. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39:1091–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosa AL, Carneiro MG, Lavrador MA, Novaes AB., Jr Influence of flap design on periodontal healing of second molars after extraction of impacted mandibular third molars. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93:404–7. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.122823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGrath C, Comfort MB, Lo EC, Luo Y. Can third molar surgery improve quality of life. A 6-month cohort study? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:759–63. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(03)00150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]