Abstract

Background:

Management of furcation defects is challenging, and constantly newer therapeutic strategies are evolving. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) is successfully used alone and in combination with various agents in the furcation defects. Lately, metformin (MF), a second generation biguanide has gained popularity owing to its osteogenic potential.

Aims and Objectives:

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the clinical and radiographic effectiveness of open flap debridement (OFD) and PRF when compared to OFD + PRF + 1% MF gel in the management of mandibular Grade II furcation defects.

Materials and Methods:

Thirty mandibular grade II furcation defects were stratified into two groups; in one group OFD and PRF is used, and the other group had an additional MF gel with PRF in OFD. Clinical parameters such as plaque index, modified sulcus bleeding index, probing pocket depth (PD), relative vertical attachment level (RVAL), and relative horizontal attachment level (RHAL) were recorded at baseline and at 6 months. Radiovisiography and ImageJ software were used to evaluate the intrabony defect depth.

Results:

The OFD + PRF + MF group showed significantly higher probing PD reduction, RVAL and RHAL gain than the OFD + PRF group.

Conclusions:

PRF when combined with a potential osteogenic agent like MF can provide a better therapeutic benefit to a furcation involved tooth.

Keywords: Furcation defects, metformin, open flap debridement, platelet-rich fibrin

INTRODUCTION

Periodontal diseases encompass a set of inflammatory conditions resulting in the obliteration of the supporting tissues of the teeth, particularly bone, through osteoclastic resorption.[1] A clinician's vision has always been on efforts to regenerate lost alveolar bone. This holds true, especially in furcation areas where the ease of access to instrumentation has always been a challenge.[2] The presence of proximal deep furcation defects may not only affect the response to therapy of an affected tooth adversely but also the prognosis of adjacent teeth.[3,4,5]

To overcome these challenges, newer therapeutic modalities such as Emdogain, PRP, introduction of growth factors, and bone morphogenetic proteins have been initiated.[6,7,8,9] Lately, metformin (MF), an antidiabetic agent, is successfully used as a local drug delivery agent in chronic periodontitis patients.[10] Literature has suggested that MF possesses osteogenic potential and it is also established that MF induces growth of osteoblast precursor cells.[10] Histological studies have supported the role of MF as an anti-inflammatory agent, and thus, it is known to hinder bone resorption in a periodontitis model.[10] A significant improvement in the clinical parameters has been reported when MF is used in conjunction with SRP in chronic periodontitis cases.[10]

The aim of the present study was to assess the clinical as well as radiographic effectiveness of open flap debridement (OFD) + platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) and OFD + PRF + 1% MF gel in the management of mandibular Grade II furcation defects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

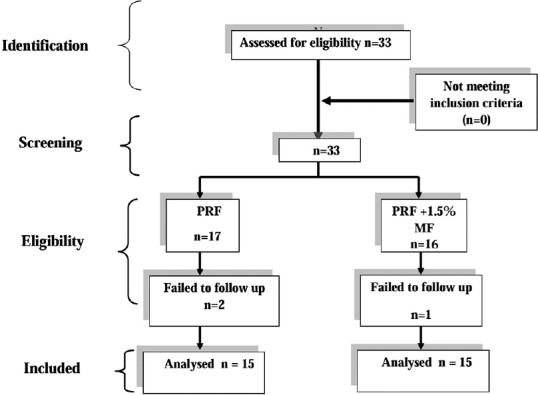

This clinicoradiographic single center, longitudinal, double-blind study was performed for a duration of 6 months. A total of 30 sites in 22 patients having Grade II furcation involved mandibular molars were chosen from the outpatient department of Periodontology. The selected sites were stratified arbitrarily with the toss of coin into two groups. The distribution of study participants, as well as the study design, is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study design; n - Number of participants

Group A: Test group consisted of 15 buccal grade II furcation defects that were managed by OFD followed by PRF and 1% MF gel

Group B: Control group consisted of 15 buccal grade II furcation defects that were managed by OFD followed by PRF only.

After getting the approval from the institutional ethical board, the participants were verbally informed about the study protocol and written informed consent was received. Diagnosis of chronic periodontitis was made according to the American Academy of Periodontology, 1999 World Workshop Consensus.[11] The set criteria for inclusion in the study were:

Buccal Grade II furcation defect in mandibular molars which were endodontically vital[12]

Asymptomatic mandibular first and second molars with a radiolucency in the furcation area on the radiovisiography (RVG)

Probing pocket depth (PD) >5 mm and horizontal PD >3 mm after phase 1 therapy.[13,14]

The exclusion criteria for the study were:

Diabetic patients, patients with cardiac disorders or bleeding disorders, immunocompromised (e.g., HIV individuals) individuals, and patients on long-term medications such as corticosteroids or calcium channel blockers which may affect the bone metabolism

Patients with reported allergies to medications

Pregnant or lactating females

Patients with a habit of tobacco chewing/smoking

Individuals with poor oral hygiene

Teeth with interproximal intrabony defects and gingival recession

Mobility of tooth Grade II or teeth with furcation caries was also excluded.

The enrolled patients signed informed consent form in English as well as in Hindi language to willingly participate in the research. Comprehensive medical and dental histories were taken to assess for any contraindications. The clinical parameters incorporated site-specific plaque index (PI),[15] modified sulcus bleeding index (mSBI),[16] PD from the gingival margin, relative vertical attachment level (RVAL), and relative horizontal attachment level (RHAL) from the apical level of custom-made acrylic stents with grooves to ensure a reproducible placement of a periodontal probe (PCP-UNC 15, Hu Friedy® for vertical measurement) and Naber's probe (Hu Friedy® PQ2N6-for horizontal measurement). All the clinical parameters were examined at baseline and 6 months postoperatively.

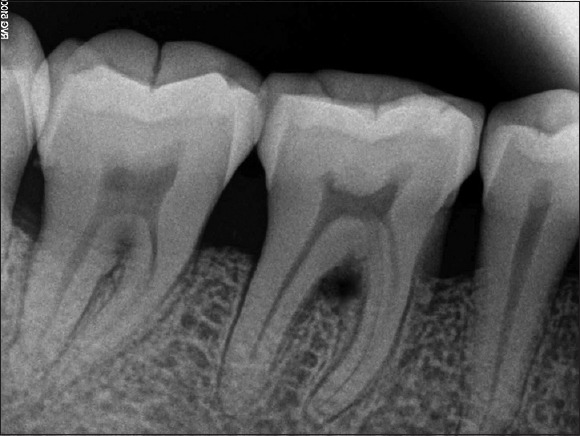

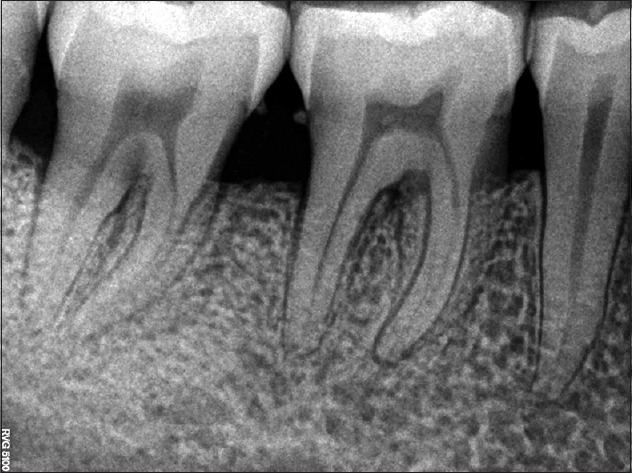

For evaluation of intrabony defect (IBD) depth, distance from the furcation fornix to the base of the defect was taken into consideration. RVG images were obtained preoperatively and 6-month postoperatively. Radiolucency at the furcation site was measured from the furcation fornix, in millimeters.[17] Image J software (1.50i, National Institutes of Health, USA) was used to measure the bone defect depth.

Presurgical phase included phase I therapy after which sites were randomly chosen for test and control group with the toss of a coin.

Surgical phase

The PRF was formed as per the procedure stated by Choukroun et al.[18] Just before the surgical procedure, intravenous blood (by venipuncturing the antecubital vein) was collected in three, 10-ml sterilized test tubes. No anticoagulant was added to the tubes and instantly centrifuged in centrifugation machine (REMI, Mumbai) at 3000 RPM for 10 min. This ensured the formation of structured fibrin clot in the center of the tube, just in the middle of the red corpuscles at the base and acellular plasma (platelet-poor plasma [PPP]) at the top. PRF was separated from RBCs using sterile tweezers and scissors just after the removal of PPP. Then, it was transferred onto sterile gauze compress so as to squeeze out the serum out of a stable PRF membrane. This membrane thus formed is easy to handle and be manipulated by the operator. PRF, thus prepared, was used in two ways in both groups, one to fill the defect (with or without 1% MF gel) and second as a protective barrier membrane over the defect space.[19]

Preparation of 1% metformin gel

MF gel was prepared as described by Mohapatra et al.[20] The necessary ingredients needed for the gel preparation were weighed precisely. Initially, a dry gellan gum powder and distilled water were mixed with a magnetic stirrer at 95°C for a period of 20 min to facilitate the formation of hydrous gellan gum. The temperature was maintained at ≥80°C, and mannitol (required amount) was added to the solution formed. Subsequent to this, MF (weighed quantity) was incorporated in addition to the citric acid, sucralose and preservatives such as propylparaben and methylparaben. It is important to continuously stir the mixture all through the procedure. To this mix, the required amount of liquefied sodium citrate was incorporated. This blend produced a gel once; it was cooled at around 20°C–25°C. Hence, the concentration of final MF gel was adjusted to ~1%.

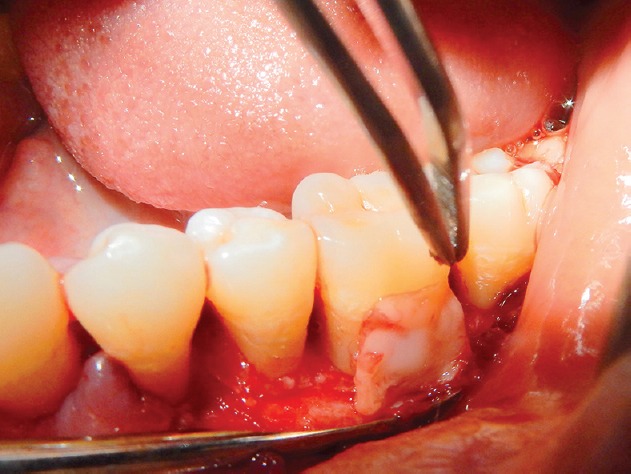

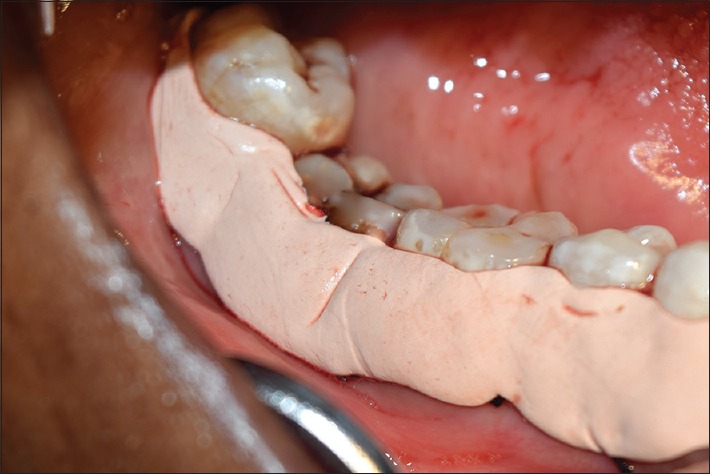

Before surgery, patients rinsed with 0.12% chlorhexidine digluconate (Hexidine® ICPA). Subsequent to administering local anesthesia, intracrevicular incisions were given at buccal and lingual surfaces, and mucoperiosteal flaps were reflected [Figure 2].[13] Thorough defect debridement was done followed by root planing with area-specific curettes (Gracey curettes Hu-friedy®) and furcation curettes (Quetin SQBL 16 Hu-friedy®). The prepared gel of 1% MF was mixed with PRF and placed into the furcation defect following OFD in group A [Figure 3], whereas in group B, PRF alone was placed into the furcation defect. The furcation defects of both the groups were further covered by a PRF membrane to provide protection and space [Figure 4]. The mucoperiosteal flaps were repositioned and sutured with 3-0 non-absorbable silk surgical sutures [Figure 5]. The treated area was covered by means of periodontal dressing [Figure 6]. Postoperative instructions were given. The prescribed medications were 500 mg amoxicillin, 400 mg metronidazole and 400 mg ibuprofen t. i. d all for 7 days. Patients were asked to rinse chlorhexidine digluconate rinses (0.12%) (Hexidine® ICPA), for the next 15 days twice daily. Suture removal was performed 10 days postsurgery. The treated areas were then gently cleansed, and participants were instructed to resume brushing in the operated area with a soft toothbrush. Soft and hard tissue evaluations were done 6 months post-surgery. For hard tissue reevaluation, second RVG images of the same study site were taken, and furcation bone defect measurements were reevaluated [Figures 7 and 8].

Figure 2.

Reflection of mucoperiosteal flap and debridement

Figure 3.

Placement of platelet-rich fibrin and 1% metformin gel mixture

Figure 4.

Application of platelet-rich fibrin membrane to cover the defects

Figure 5.

Repositioning and suturing with interdental sutures

Figure 6.

Application of periodontal dressing

Figure 7.

Preoperative radiovisiography for intrabony defect measurement

Figure 8.

Six-month postoperative radiovisiography depicting intrabony defect fill

Radiographic assessment of intrabony defects

The depth of IBD was evaluated at baseline and 6 months with the help of an image analyzer (Image J®) IBD was measured on the radiograph by computing the vertical distance from the crest of the alveolar bone to the base of the defect. Standardized radiographs were taken using the paralleling technique and holders so as to obtain films as reproducible as possible. All the radiographic images were evaluated in a single reference centre by the masked evaluator.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis for the periodontal parameters was done using a “Paired t-test” (intragroup) and one-way ANOVA (intergroup) for comparative evaluation at two different time intervals for clinical and radiographic parameters. For all the tests, P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

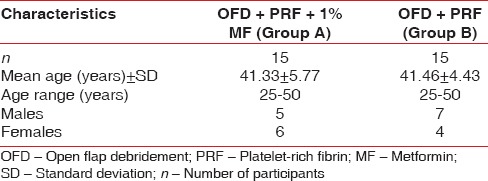

The characteristics of the study groups are represented in Table 1. All the patients completed the study. There were no statistical differences in the mean age and sex among the test and control groups. No undesirable reactions related to the treatment procedure were noted among patients. Satisfactory wound healing was observed at all the sites involved in the study. Results of the study are expressed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

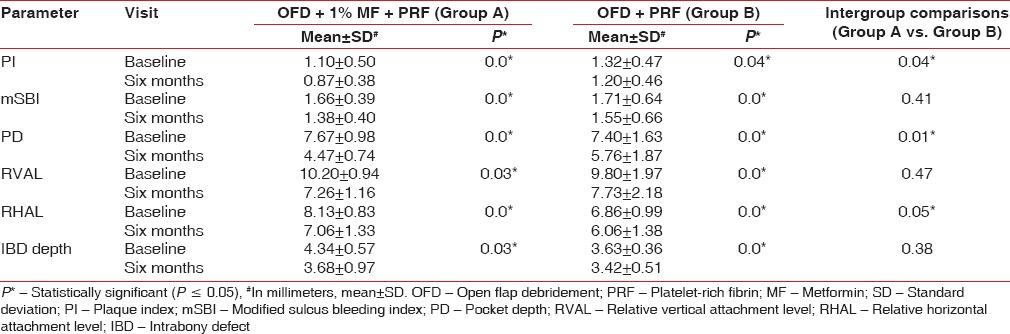

Table 2.

Clinical and radiographic parameters in study groups at baseline and 6 months

Primary outcome measures were RVAL, RHAL, and IBD depth, whereas secondary outcome measures were PI, mSBI, and PD.

A statistically significant reduction in both PI and mSBI was observed at 6 months from baseline in both the study groups. This indicates uniformity in oral hygiene maintenance by all the study participants.

A highly significant improvement in PD was observed in both the study groups at 6 months from baseline. On comparing intergroup data, Group A showed highly significant reduction in PD (P = 0.01) compared to Group B.

The mean score of RVAL at 6 months for Group A showed no significant difference compared to the Group B score. However, the mean scores of RHAL and IBD at 6 months showed significant improvement compared to the baseline scores (P ≤ 0.05) in both the study groups. At 6 months, the mean score of RHAL for Group A showed statistically significant improvement compared to the scores of Group B. On the other hand, at 6 months, the mean score of IBD, 3.68 ± 0.97 for Group A showed no significant improvement over Group B (3.42 ± 0.51) (P > 0.05). None of the treated defects progressed to degree III.

DISCUSSION

The present study investigated the effectiveness of PRF when combined with MF in the management of furcation defects. At baseline all the values were almost identical and statistically nonsignificant. At 6 months, the mean score of PI for Group A showed a significant improvement over Group B, (P ≤ 0.05). The closely monitored regimen of maintenance was identical in both the study participants. The difference in the results at 6 months can clearly be attributed to the complete or partial closure of the furcations.[13,21,22] This improvement is in accordance with the studies of Caffesse et al. and Pradeep et al.[13,22] At 6 months, the mean score of mSBI showed significant improvement from baseline scores in both the study groups. Similar observations were recorded by Thorat et al. and Pradeep et al.[13,23]

Probing depth is not only a sought-after result of periodontal regeneration procedure but also an important factor for patients oral self-care strategy. At 6 months, significant reduction in PD was observed in both the study groups. On intergroup comparisons a highly significant value was obtained favoring Group A (P ≤ 0.01). The observations indicate significant gain in clinical attachment level which is a consequence of improved tissue healing following surgical periodontal treatment.[6,13,24,25]

Similarly, the mean scores of RVAL of both the groups showed significant improvement at 6 months from baseline. However, intergroup comparisons yielded nonsignificant results. Our findings are in agreement with the findings of Bowers et al., Anderegg et al., Selvig et al., Machtei et al., and Black et al.[26,27,28,29,30]

A significant improvement in intergroup comparisons of RHAL at baseline and 6 months was also found. Presurgical RHAL has confirmed a contrary association with furcation closure, increase in horizontal probing depth were more or less associated with diminished percentage of sites demonstrating complete clinical closure.[26] This was further proven by the results of our study. Complete furcation closure was obtained in 90% of early furcation lesions (≤4 mm).[26] We attained almost matching results where Group A containing MF was significantly better compared to Group B in furcation closure. This can be attributed to MF because it is a known activator of proliferation and differentiation of local progenitor cells leading to the formation of new bone matrix. Also, MF significantly reduces the intracellular reactive oxygen species and apoptosis of local progenitor cells which improve the production of type I collagen leading to enhanced healing.[10] Thus, generous bone fill was obtained in Grade II furcations in the Group A. A 6 months evaluation period in our study was based on several studies which revealed that dimensional changes of periodontal tissues ensuing from surgical healing sometimes continue to occur up to 6 months.[31,32]

The IBD depths at 6 months did not differ much in both the groups. The reason for this seems to be because of slow release of growth factors such as platelet-derived growth factor, transforming growth factor beta 1 in the case of PRF, and insulin-like growth factor-1 expression in the case of MF. The release of all these factors has been found to be timebound in different studies. Furthermore, a study by Borges et al. revealed that 80 weeks of MF treatment induces very modest increase in bone mineral density, thus these possible bone sparing and bone formative effects of MF may be linked to the passage of time.[33] Studies indicate that 1% MF worked best and superior to 0.5% and 1.5% concentrations 34 and was retained in the target compartment suggesting a sustained release of drug until 4 weeks, when used as intrapocket gel.[21] Thus, it seems the growth factors obtained from both PRF as well as MF have a wash off period limiting the accuracy over the 6 months period of the study.[35] Another factor to be taken into consideration is that, highest probability of clinical furcation closure and IBD reduction was detected in early class II defects, and in general, the results were proportionate to the extent of furcation involvement – the earlier, less severe the defect, the greater the likelihood of achieving complete clinical furcation closure. Furthermore, anatomical challenges such as short-root trunks architecture of furcation entrance, root divergence, root surface irregularities and curvatures, interradicular root surfaces, and root concavities all affect the regeneration of furcation defects in mandibular molars predominantly first molars possibly affecting the IBD reduction.[26]

In the present study, the efficacy of PRF with MF was assessed for 6 months duration. The evaluative period could have been longer to elucidate the role of MF in inducing bone formation. Latest advances in radiographic techniques like cone-beam computed tomography could have been utilized to assess furcation defects.

CONCLUSIONS

The observations of our study revealed that MF may exhibit a beneficial effect on the alveolar bone by increasing osteoblast differentiation. Although we are unsure about definitive and conclusive remarks regarding the effect of MF, the present findings appear to be meaningful with regards to the beneficial effects of MF on bone tissues in Grade II furcation defects. However, more longitudinal, multicentric, randomized controlled clinical and interventional trials will need to be conducted to know its clinicohistologic and radiographic effects on the healing of the bone, thereby confirming the findings of our study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Van Dyke TE, Serhan CN. Resolution of inflammation: A new paradigm for the pathogenesis of periodontal diseases. J Dent Res. 2003;82:82–90. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leon LE, Vogel RI. A comparison of the effectiveness of hand scaling and ultrasonic debridement in furcations as evaluated by differential dark-field microscopy. J Periodontol. 1987;58:86–94. doi: 10.1902/jop.1987.58.2.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nordland P, Garrett S, Kiger R, Vanooteghem R, Hutchens LH, Egelberg J, et al. The effect of plaque control and root debridement in molar teeth. J Clin Periodontol. 1987;14:231–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1987.tb00972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Claffey N, Egelberg J. Clinical characteristics of periodontal sites with probing attachment loss following initial periodontal treatment. J Clin Periodontol. 1994;21:670–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1994.tb00785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehnevid H, Jansson LE. Effects of furcation involvements on periodontal status and healing in adjacent proximal sites. J Periodontol. 2001;72:871–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.7.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffmann T, Richter S, Meyle J, Gonzales JR, Heinz B, Arjomand M, et al. A randomized clinical multicentre trial comparing enamel matrix derivative and membrane treatment of buccal class II furcation involvement in mandibular molars. Part III: Patient factors and treatment outcome. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:575–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.00947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pradeep AR, Pai S, Garg G, Devi P, Shetty SK. A randomized clinical trial of autologous platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of mandibular degree II furcation defects. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36:581–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nevins M, Camelo M, Nevins ML, Schenk RK, Lynch SE. Periodontal regeneration in humans using recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB (rhPDGF-BB) and allogenic bone. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1282–92. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.9.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Díaz-Sánchez RM, Yáñez-Vico RM, Fernández-Olavarría A, Mosquera-Pérez R, Iglesias-Linares A, Torres-Lagares D, et al. Current approaches of bone morphogenetic proteins in dentistry. J Oral Implantol. 2015;41:337–42. doi: 10.1563/AAID-JOI-D-13-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cortizo AM, Sedlinsky C, McCarthy AD, Blanco A, Schurman L. Osteogenic actions of the anti-diabetic drug metformin on osteoblasts in culture. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;536:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:1–6. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mansouri SS, Ghasemi M, Darmian SS, Pourseyediyan T. Treatment of mandibular molar class II furcation defects in humans with bovine porous bone mineral in combination with plasma rich in growth factors. J Dent (Tehran) 2012;9:41–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pradeep AR, Nagpal K, Karvekar S, Patnaik K, Naik SB, Guruprasad CN, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin with 1% metformin for the treatment of intrabony defects in chronic periodontitis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2015;86:729–37. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.140646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Müller HP, Eger T. Furcation diagnosis. J Clin Periodontol. 1999;26:485–98. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.1999.260801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silness J, Loe H. periodontal disease in pregnancy. ii. correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condtion. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121–35. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mühlemann HR, Son S. Gingival sulcus bleeding – A leading symptom in initial gingivitis. Helv Odontol Acta. 1971;15:107–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prathap S, Hegde S, Kashyap R, Prathap MS, Arunkumar MS. Clinical evaluation of porous hydroxyapatite bone graft (Periobone G) with and without collagen membrane (Periocol) in the treatment of bilateral grade II furcation defects in mandibular first permanent molars. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2013;17:228–34. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.113083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choukroun J, Adda F, Schoeffer C, Vervelle A. PRF: An opportunity in perio-implantology. Implant. 2000;42:55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bajaj P, Pradeep AR, Agarwal E, Rao NS, Naik SB, Priyanka N, et al. Comparative evaluation of autologous platelet-rich fibrin and platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of mandibular degree II furcation defects: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Periodontal Res. 2013;48:573–81. doi: 10.1111/jre.12040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohapatra M, Parikh RK, Gohel MC. Formulation, development and evaluation of patient friendly dosage forms of metformin, part-II: Oral soft gel formulation, development and evaluation of patient friendly dosage forms of metformin. J Pharm. 2008;2:172–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rao NS, Pradeep AR, Kumari M, Naik SB. Locally delivered 1% metformin gel in the treatment of smokers with chronic periodontitis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2013;84:1165–71. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.120298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caffesse RG, Smith BA, Duff B, Morrison EC, Merrill D, Becker W, et al. Class II furcations treated by guided tissue regeneration in humans: Case reports. J Periodontol. 1990;61:510–4. doi: 10.1902/jop.1990.61.8.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thorat M, Pradeep AR, Pallavi B. Clinical effect of autologous platelet-rich fibrin in the treatment of intra-bony defects: A controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38:925–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsao YP, Neiva R, Al-Shammari K, Oh TJ, Wang HL. Effects of a mineralized human cancellous bone allograft in regeneration of mandibular class II furcation defects. J Periodontol. 2006;77:416–25. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lekovic V, Camargo PM, Weinlaender M, Vasilic N, Aleksic Z, Kenney EB, et al. Effectiveness of a combination of platelet-rich plasma, bovine porous bone mineral and guided tissue regeneration in the treatment of mandibular grade II molar furcations in humans. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:746–51. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bowers GM, Schallhorn RG, McClain PK, Morrison GM, Morgan R, Reynolds MA, et al. Factors influencing the outcome of regenerative therapy in mandibular class II furcations: Part I. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1255–68. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.9.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderegg CR, Martin SJ, Gray JL, Mellonig JT, Gher ME. Clinical evaluation of the use of decalcified freeze-dried bone allograft with guided tissue regeneration in the treatment of molar furcation invasions. J Periodontol. 1991;62:264–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.1991.62.4.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Selvig KA, Kersten BG, Wikesjö UM. Surgical treatment of intrabony periodontal defects using expanded polytetrafluoroethylene barrier membranes: Influence of defect configuration on healing response. J Periodontol. 1993;64:730–3. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.8.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Machtei EE, Cho MI, Dunford R, Norderyd J, Zambon JJ, Genco RJ, et al. Clinical, microbiological, and histological factors which influence the success of regenerative periodontal therapy. J Periodontol. 1994;65:154–61. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.2.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Black BS, Gher ME, Sandifer JB, Fucini SE, Richardson AC. Comparative study of collagen and expanded polytetrafluoroethylene membranes in the treatment of human class II furcation defects. J Periodontol. 1994;65:598–604. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.6.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosling B, Nyman S, Lindhe J, Jern B. The healing potential of the periodontal tissues following different techniques of periodontal surgery in plaque-free dentitions. A 2-year clinical study. J Clin Periodontol. 1976;3:233–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1976.tb00042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Westfelt E, Bragd L, Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Nyman S, Lindhe J, et al. Improved periodontal conditions following therapy. J Clin Periodontol. 1985;12:283–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1985.tb02294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borges JL, Bilezikian JP, Jones-Leone AR, Acusta AP, Ambery PD, Nino AJ, et al. A randomized, parallel group, double-blind, multicentre study comparing the efficacy and safety of avandamet (rosiglitazone/metformin) and metformin on long-term glycaemic control and bone mineral density after 80 weeks of treatment in drug-naïve type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13:1036–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pradeep AR, Rao NS, Naik SB, Kumari M. Efficacy of varying concentrations of subgingivally delivered metformin in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2013;84:212–20. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.120025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kassem AA, Issa DA, Kotry GS, Farid RM. Thiolated alginate-based multiple layer mucoadhesive films of metformin forintra-pocket local delivery: In vitro characterization and clinical assessment. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2017;43:120–31. doi: 10.1080/03639045.2016.1224895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]