Abstract

Insulin replacement therapy is the standard of care for patients with type 1 and advanced type 2 diabetes mellitus. Porcine and bovine pancreatic tissue was the source of the hormone for many years, followed by semisynthetic human insulin obtained by modification of animal insulin. With the development of recombinant DNA technology, recombinant (biosynthetic) human insulin became available in large amounts by biosynthesis in microorganisms (Escherichia coli, yeast) providing reliable supplies of the hormone worldwide at affordable costs. The purity and pharmaceutical quality of recombinant human insulin was demonstrated to be superior to animal and semisynthetic insulin and patients with diabetes could be safely and effectively transferred from animal or semisynthetic human insulin to recombinant human insulin with no change expected in insulin dose. The decision for change remains a clinical objective, follow-up after any change of insulin product is recommended to confirm clinical efficacy. This review provides a summary and retrospective assessment of early clinical studies with recombinant insulins (Insuman®, Humulin®, Novolin®).

Keywords: Recombinant human insulin, clinical studies, Insuman formulations, NPH insulin, premix insulins, review

Insulin preparations extracted from bovine or porcine pancreatic tissue have served as the mainstay of diabetes therapy since 1923, when commercial production was established in Europe and the US.1 Animal insulin sources became a limiting factor to provide sufficient supply of insulin for the increasing clinical demand of insulin worldwide. When the molecular structure of human insulin was elucidated, attempts were made at total chemical synthesis but failed to provide a clinically relevant supply.2,3 A next step towards obtaining clinically suitable human insulin was processing of animal insulin by exchange of amino acids and extensive purification.4–6 The modified material was addressed as ‘semisynthetic human insulin’ and all pharmaceutical formulations (regular, neutral protamine Hagedorn [NPH], premixed insulins) were manufactured from such semisynthetic insulin. At the time when semisynthetic human insulin was introduced to the market, there was an intensive and partly acrimonious discussion about this change in insulin source and about the clinical relevance of the need for ‘human insulin’. When clinical studies confirmed the comparable efficacy of this new type of insulin, the discussion subsequently focused on the improvements related to further purification, in particular, in decreasing the formation of insulin-directed antibodies due to therapy, and reducing the risk of local and systemic allergic reactions.

‘Recombinant human insulin’ became available in large amounts by recombinant DNA technology using fermentation in microorganisms (bacteria or yeast). Recombinant insulin has a superior level of purity and consistent quality compared with semisynthetic insulin. The process of biosynthesis was initially developed by Genentech and rapidly applied on an industrial scale by Eli Lilly,2,6 followed by pharmaceutical and clinical process development at Novo Nordisk and Sanofi (formerly Hoechst AG/Hoechst Marion Roussel/Aventis). These companies are the lead manufacturers of recombinant human insulin (see Table 1), the human insulin profiles and clinical aspects have been described and reviewed extensively.7–9 Since its first introduction to clinical therapy in 1982, recombinant human insulin represents the standard of care,10–12 even after the introduction of insulin analogues.12 The standard of care in diabetes therapy is addressed by international treatment guidelines.10–12 Many clinical studies with recombinant human insulins submitted for regulatory approval have not been published in detail. Bioequivalence studies performed with recombinant Insuman® (Sanofi, Paris, France) have been reported recently.13 “Scientific Summaries and Public Assessment Reports” of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for marketed human insulins including Insuman14 are found at the EMA website, and approval information at the website of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).15

Table 1: Overview of Original Recombinant Human Insulins.

| Manufacturer | Sanofi | Novo Nordisk | Eli Lilly |

|---|---|---|---|

| Approval | 1997 EU: Insuman® (HR1799, HPR) | 1991 US | 1982 US, EU*** |

| Production (Host cell) | Bacteria (Escherichia coli) | Yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) | Bacteria (Escherichia coli) |

| Lead trade name | Insuman® | Novolin® (US) | Humulin® (US) |

| Formulations: Regular: Basal: Premixed: |

Insuman® Rapid Insuman® Basal Insuman® Comb 15/25/30/50 |

Novolin® R Novolin® N Novolin® 70/30* |

Humulin® R Humulin® N Humulin® 70/30 |

*In EU Actraphane® 30/70; **in EU Huminsulin 30/70; ***national approval.

In this review, we report on unpublished pivotal clinical studies with recombinant Insuman documenting the efficacy and safety of semisynthetic and recombinant Insuman, and comparing recombinant Insuman with marketed formulations of Humulin® (Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, Indiana, US). Furthermore, the use of insulin formulations in clinical practice is discussed to review the place of recombinant human insulin in routine clinical practice of today.

Clinical Studies with Recombinant Human Insulins

The initial clinical studies with recombinant human insulins (Humulin, Novolin®, Insuman) explored the change from animal insulin to semisynthetic insulin and to recombinant human insulin formulations. Clinical studies in patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes included paediatric and pregnant subjects.16,17 Clinical pharmacology studies using the euglycaemic clamp technique were performed to demonstrate bioquivalence between the insulin formulations.13 The clinical studies of 6 to 12 months duration focused on clinical efficacy and safety. Safety aspects comprised the incidence of hypoglycaemia, the perception of decreasing glucose levels (hypoglycaemic awareness) and the level of manifestations of antigenicity (hypersensitivity reactions). Special interest was directed at the antigenicity response (insulin-directed antibodies, and antibodies to Escherichia coli or Saccharomcyes cerevisiae proteins) remaining after extensive purification of the preproinsulin.18–23 Clinical study objectives were incidence and severity of hypoglycaemia,24–26 injection-site reactions and adverse events (AEs) profile. Glycaemic targets (glycated haemoglobin [HbA1c], fasting blood glucose [FBG]) were usually defined individually for each subject by the investigators. Insulin dose titration did not yet follow a fasting treat-to-target concept at that time.27

Humulin and Novolin

The pharmaceutical formulations of recombinant human insulins provided by the key manufacturers include soluble regular insulin, crystalline NPH insulin and premixed formulations (soluble insulin and NPH insulin in fixed ratios). The formulations were found to be bioequivalent and similar in efficacy and safety to those of semisynthetic insulin.7–9,13,19 Bioequivalence studies comparing porcine insulin with recombinant human insulin showed small differences in the time–action profile, but were comparable in clinical efficacy.19

Clinical studies with semisynthetic and recombinant insulin derived from baker’s yeast (Novolin, Novo Nordisk, Copenhagen, Denmark) showed similar profiles in efficacy and safety and established that patients with diabetes can be safely and effectively transferred from semisynthetic human insulin to recombinant human insulin with no change expected in the insulin dose.28–31

Clinical pharmacology studies with recombinant human insulin produced by fermentation in E. coli (Humulin, Eli Lilly, Indianapolis) established bioequivalence of semisynthetic and recombinant Humulin formulations.14,32,33 Extensive clinical studies were performed in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes14,33–36 to confirm consistent clinical efficacy when transferring patients to the recombinant formulations.14,33,34

Insuman

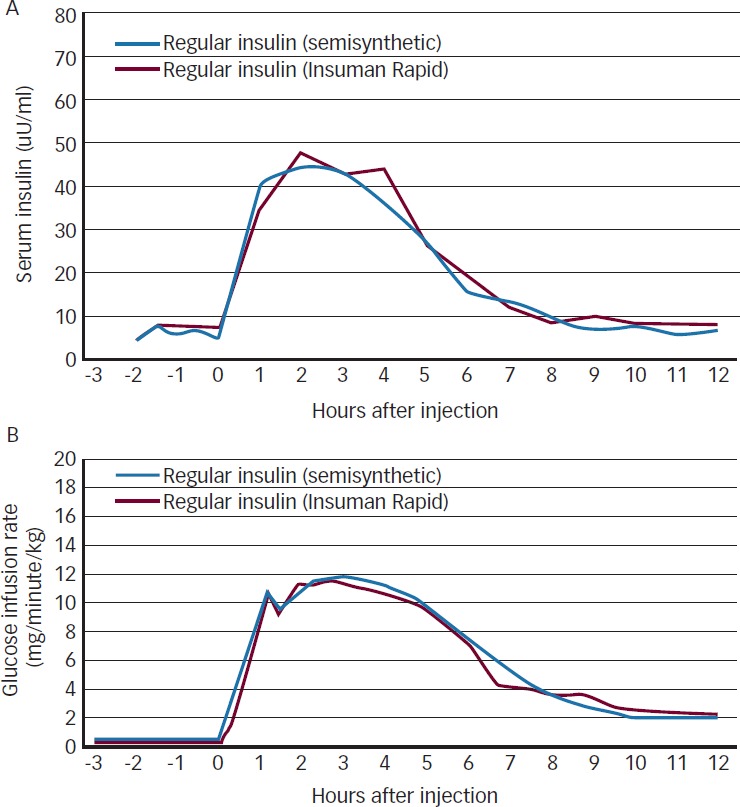

Recombinant Insuman was approved in Europe in 1997 and launched in 1999. The early clinical studies are summarised in the EMA approval documents.37 The formulations comprise regular soluble insulin (Insuman Rapid), an intermediate-acting insulin suspension that contains isophane insulin (Insuman Basal), and premixed combinations of regular insulin and intermediate-acting insulins (Insuman Comb).13,38 During early studies, the bioequivalence of formulations based on semisynthetic insulin and recombinant Insuman was established (see Figure 1),39 subsequently bioequivalence studies for comparison with marketed recombinant insulin formulations were performed13 and followed by the clinical studies reviewed here.

Figure 1: Comparison of Pharmacokinetic (A) and Pharmacodynamic (B) Profiles of Semisynthetic Regular Insulin and Recombinant Regular Insulin (Insuman Rapid) after a Single Dose Injection of 0.3 U/kg in 12 Healthy Subjects Using the Euglycaemic Clamp Technique39.

Two pivotal clinical studies with recombinant Insuman were conducted in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes investigating the efficacy and safety of the change from semisynthetic insulin to recombinant Insuman,40 and in comparison with recombinant insulin formulations of Huminsulin®.41 An overview of the patient characteristics and the key efficacy and safety results of the two studies are provided in Table 2.

Table 2: Summary of Results from Two Pivotal Clinical Studies Conducted with Recombinant Human Insulin Formulations of Insuman® in Patients with Diabetes.

| Parameter | Study 140 | Study 241 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human insulin used | Insuman® (Recombinant) N=288 | Human insulin (Semisynthetic) N=289 | Insuman® (Recombinant) N=236 | Huminsulin® (Recombinant) N=234 |

| Formulations used | NPH (crystalline, basal) in free combination with or without regular insulin Premixed (25/75, 30/70) in fixed combination | NPH (crystalline, basal), in free combination with or without regular insulin or premixed Premixed (30/70) in fixed combination | ||

| Number of patients in Monotherapy (NPH or regular) Free combination (basal-bolus) Premixed combination (± other insulin) |

0 213 (74%) 75 (26%) |

0 212 (73%) 77 (27%) |

67 (28%) 29 (12%) 140 (59%) |

59 (25%) 25 (11%) 150 (64%) |

| Study design | Randomised, double-blind | Randomised, open-label | ||

| Study duration | 24 weeks | 54 weeks | ||

| Number of patients with diabetes: Type 1 Type 2 |

192 (67%) 96 (33%) |

196 (68%) 93 (32%) |

Only insulin-naÏve type 2 diabetes patients were included | |

| Age (years) | 41.9 ± 15.5 | 42.1 ± 15.6 | 58.3 ± 10.0 | 58.5 ± 9.9 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.9 ± 3.6 | 24.7 ± 3.7 | 28.9 ± 4.7 | 28.5 ± 5.2 |

| Duration of diabetes (years) | 11.1 ± 8.9 | 11.7 ± 9.6 | 9.9 ± 6.3 | 10.4 ± 6.9 |

| HbA1c at baseline (%) | 11.51 ± 2.73 | 11.57 ± 2.89 | 9.7 ± 1.9 | 9.9 ± 2.0 |

| HbA1c at study end (%) | 10.57 ± 2.40 | 10.72 ± 2.49 | 8.0 ± 1.6 | 8.1 ± 1.7 |

| HbA1c change from baseline to endpoint | -0.94 ± 2.45 | -0.85 ± 2.70 | -1.76 ± 0.09 | -1.80 ± 0.09 |

| Fasting blood glucose at baseline (mmol/l) | 8.83 ± 3.00* | 8.70 ± 3.53* | 12.40 ± 3.50 | 12.46 ± 3.72 |

| Fasting blood glucose at study end (mmol/l) | 8.11 ± 3.85* | 8.52 ± 4.53* | 8.52 ± 2.57 | 8.75 ± 3.12 |

| Total insulin dose at baseline, U/day (U/kg) | 35.6 ± 12.7 (0.55 ± 0.19) |

36.2 ± 15.2 (0.58 ± 0.23) |

20.0 ± 11.7 (0.26 ± 0.17) |

20.8 ± 12.5 (0.27± 0.17) |

| Total insulin dose at study end, U/day (U/kg) | 38.5 ± 8.5 (0.60 ± 0.11) |

39.6 ± 9.6 (0.64 ± 0.14) |

42.3 ± 31.6 (0.53 ± 0.34) |

38.1 ± 22.6 (0.49 ± 0.27) |

| Change in bodyweight, kg (baseline to study endpoint) | +0.3 ± 3.0 | +0.3 ± 2.7 | +3.5 ± 4.7 | +3.2 ± 5.3 |

| Number of patients with hypoglycaemia Symptomatic overall Symptomatic nocturnal Severe |

150 (52%) Not reported 7 (2.4%) |

132 (46%) Not reported 11 (3.8%) |

95 (40%) 18 (8%) 3 (1.3%) |

104 (44%) 16 (7%) 2 (0.9%) |

| Number of patients reporting adverse events Type 1 Type 2 Serious (all patients) |

87 (45%) 44 (46%) 20 (6.9%) |

78 (40%) 51 (55%) 25 (8.7%) |

- 131 (56%) 33 (14%) |

- 138 (59%) 31 (13%) |

| Number of patients with injection-site reactions | 5 (1.7%) | 4 (1.4%) | 7 (3.0%) | 1 (0.4%) |

Data are mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless not indicated elsewhere *In this study, little emphasis was placed to collect fasting blood glucose (FBG) and in many centres, patients were generally seen in late morning or afternoon in keeping routine clinical practice. Therefore, results for FBG only reflect 33% of patients in each group. HbA1c = glycated haemoglobin; NPH = neutral protamine Hagedorn.

In a first multinational, randomised, double-blind 24-week study including 575 adult patients with diabetes (87% with type 1, 33% type 2), patients were stratified either to a free combination of NPH insulin (crystalline, basal), with or without regular insulin, or to a fixed combination of Insuman Comb 25/75 and randomised to either recombinant or semisynthetic insulin preparations in each group. Of the randomised patients, 96% had been treated with insulin prior to the study and 37% of patients had a history of diabetic late complications, and 42% had frequent mild hypoglycaemic episodes during the year before start of the study. The glycaemic target was to achieve a FBG value of 140 mg/dl or lower.

Both recombinant and semisynthetic human insulin achieved a similar decrease of HbA1c and FBG after 24 weeks. Subgroups analyses by age, gender, type of diabetes, prior insulin treatment and presence of diabetic late complications demonstrated similar outcomes. There has been an intense discussion about perception of hypoglycaemia in patients previously treated with animal insulins after changing to semisynthetic or recombinant human insulins.24,25 In this study no difference in incidence of symptomatic hypoglycaemia and in calculated episodes per patient-year were found, as well as no change in the perception of hypoglycaemia.

Antigenicity has always been a concern when using animal insulins. However, early studies showed that antigenicity decreased markedly when changing from animal insulins to recombinant insulins. In this study, the level of insulin antibodies related to insulin exposure before treatment was very low, and there was no relevant increase after treatment with semisynthetic insulin or recombinant Insuman. In addition, there was a very low level of antibodies detected to E. coli proteins in patients treated with recombinant insulin. The absence of such proteins is particularly relevant for the pharmaceutical quality of recombinant insulins after intensive purification. The number of patients with AEs, serious AEs and with local and systemic reactions to insulin injection also did not differ between the insulin treatments.

In a second multinational, randomised, open-label 54-week study in 473 insulin-naive subjects with type 2 diabetes the efficacy and safety of recombinant Insuman was compared with recombinant Huminsulin formulations. Huminsulin formulations were selected as a comparator based on bioequivalence confirmed with Insuman.13 Treatments comprised regular insulin, crystalline NPH insulin and premixed insulins (Insuman Comb 25 and 50, Huminsulin 30/70). Selection of treatment regimen was at the discretion of the investigators and individual dose titration was applied to achieve the best possible glycaemic control for each subject.

The primary study objective was an evaluation of antigenicity and measurement of antibodies to human insulin and E. coli proteins.20–23 Further safety aspects included hypoglycaemia assessment, local or general manifestations of insulin allergy and clinical AEs during treatment.

As expected for insulin-naive type 2 subjects, the insulin antibody binding increased in both treatment groups while on insulin treatment, with no relevant difference between groups. In both groups, increased insulin antibody binding was not associated with deterioration of metabolic control or a marked increase on the insulin dose or hypoglycaemia incidence. At study endpoint, 52% and 49% of Insuman- and Huminsulin-treated subjects, respectively, had detectable insulin antibody binding. Similar results were found for E. coli antibody binding status. Only two Insuman and eight Huminsulin subjects had an increase in their E. coli protein antibody titre from baseline to endpoint.

Randomised patients had a poor glycaemic control at baseline. As a result of insulin treatment, a clinically relevant decrease from baseline to endpoint was observed in HbA1c and FBG in both treatment groups, with no statistically significant difference (see Table 2). Throughout the entire treatment phase, 40% and 44% of Insuman and Huminsulin patients reported at least one episode of symptomatic hypoglycaemia, respectively, and only a few subjects in both treatment groups reported moderate or severe hypoglycaemia during the study. The frequency and spectrum of non-serious and serious AEs were comparable in both treatment groups. Hypersensitivity events of mild or moderate intensity were reported in 12 Insuman and in one Huminsulin subject, respectively. These events were associated with pre-existing skin disorders, allergic reactions to concomitant medication or allergic diathesis. None of the 12 Insuman subjects discontinued treatment because of a hypersensitivity event. Injection-site haemorrhage occurred occasionally and was attributed to poor injection technique. Injection-site reactions42 were reduced dramatically when educational training for regular changes in injection sites along with improved injection techniques were initiated during the study. None of the subjects in either treatment group discontinued treatment because of injection site reactions.

In summary, both studies demonstrated improvements in glycaemic control and good tolerability with Insuman in type 1 and type 2 diabetes patients comparable to comparator treatment. In addition,no difference in immunogenicity between Insuman and Huminsulin or semisynthetic insulin was found, an important characteristic of recombinant insulin formulations.20–23

Clinical Use of Recombinant Human Insulin Formulations

The change from semisynthetic synthesis to recombinant rDNA technology1,2 has enabled a worldwide human insulin supply of consistent high quality. The range of different insulin formulations derived from recombinant human insulin allows for an individual patient�s tailored treatment using different regimens that have been proved effective and safe in the long term (see Table 3). Hypoglycaemia associated with insulin treatment remains one of the major challenges during therapy; to minimise the risk, close monitoring and guidance for the patient is recommended, particularly during initial and any later dose titration. Self-monitoring of fasting and post-prandial blood glucose are helpful tools to avoid or reduce hypoglycaemia and to maintain blood glucose values in the target range. Therefore, patient education and guidance is a general task of insulin therapy to ensure a continued adherence to therapy and good metabolic control.

Table 3: Clinical Parameters of Recombinant Human Insulin Formulations.

| Insulin Type | Onset of Action (Minute) | Peak Effect (Hours) | Duration of Action* (Hours) | Injection to Meal Interval (Minute) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular (rapid-acting) | Within 30 | 2.5–5 | 8–12 | 15–30 |

| NPH (intermediate-acting) | 60–90 | 4–12 | ~20 | None |

| Premixed (rapid and intermediate-acting compound) 25/75 and 30/70 50/50 |

Within 30–60 Within 30 |

2–4 1.5–4 |

~19 ~19 |

30–45 15–30 |

*Clinical duration of action depends on the insulin dose administered. Note early onset of action with regular insulin and delayed onset of action with basal insulin. NPH = neutral protamine Hagedorn.

Regular Human I nsulin

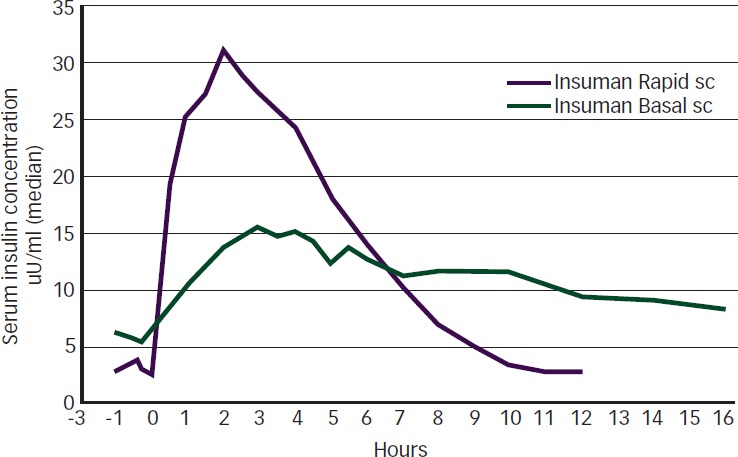

In this review, the use of formulations of recombinant insulin, in particular that of Insuman, is considered with references to daily clinical practice, in diabetes therapy of today. The clinical evidence for an injection-to-meal interval of about 30 minutes (prandial insulin) is based on the time-action profile of regular insulin,13,39 to match subcutaneous insulin absorption with ingestion of carbohydrates (see Figure 2).43,44 This ensures efficacy, albeit at the disadvantage of having to follow a more restrictive lifestyle. Subsequent studies have shown some advantage for insulin analogues in reducing the injection-to-meal interval, at the expense of increasing the cost of therapy.

Figure 2: Comparison of Serum Insulin Concentrations after Subcutaneous Singledose Injection (0.3 U/kg) of Two Insuman Formulations in 24 Healthy Subjects from Two Clamp Studies43,44.

sc = subcutaneous

In clinical emergency, Insuman Rapid may be injected or infused intravenously under strict glucose control. When using continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (insulin pumps), there is a clear clinical preference for fast-acting insulin analogues in the paediatric population. Studies with a specific formulation (Insuman Infusat) in external portable insulin pumps have shown improved stability to minimise loss of efficacy, which may result from mechanical and thermal stress. A limited number of studies have been performed for the use of Insuman Infusat in external insulin pumps, and with Insuman Implantable in intraperitoneal insulin pumps.45,46

Neutral Protamine Hagedorn Insulin

Intermediate-acting NPH insulin has been used extensively for basal insulin supply, the clinical efficacy has been well documented47,48 and the associated quality of life has not been found to be worse when compared with long-acting insulin glargine.49 There has been a discussion about once- or twice-daily injections, in the morning and at dinner time/bedtime.50 Limitations of clinical utility when using NPH insulin are the duration of action and more frequent hypoglycaemia episodes than with long-acting insulin analogues. Another limitation is the need for re-suspension immediately before each injection.

In several clinical trials, where human NPH insulin was used as the comparator for insulin glargine47,45,51,52 comparable glycaemic control was found, whereas the incidence of nocturnal hypoglycaemia was reduced with insulin glargine. Decreased incidence of hypoglycaemia was also described with other long-acting analogue insulins (detemir, degludec). NPH insulin in vials or insulin pens needs to be re-suspended immediately before the injection. This requires patient guidance and instruction to ensure consistent adherence to this procedure. Twice-daily injections of NPH insulin, in the morning and at dinner time/bedtime, are recommended by some clinicians because the time-action profile of NPH insulin does not adequately cover the 24-hour period (see Figure 2). The recommendation for twice-daily injection is valid for premixed insulins, which contain a 70-75% fraction of NPH insulin.

Premixed Insulins

In the early clinical period of using semisynthetic insulins from vials, patients used to perform the mixing themselves using two separate vials of regular insulin and NPH insulin. In several studies, premixed insulins were compared with self-mixed insulins, and formulations were developed for the use in cartridges containing a ratio of soluble to NPH insulin over a range which varied from 15/85 to 50/50.

Today, the ratio of 30/70 is most frequently used both in pens with cartridges and disposable insulin pens.38 Premixed insulins are recommended for patients with a regular lifestyle and consistent insulin requirement. When compared with premixed insulin analogues, they retain the advantages of low cost and established efficacy. The availability of reliable and affordable insulin pens has contributed markedly to patient convenience in countries with limited resources.53

Use in Pregnancy and Gestational Diabetes

Human insulin is the standard of care in pregnant women.17,54 In the early clinical studies in pregnancy, the change from animal insulins to recombinant insulin was addressed and subsequently implemented.17 Consistent glucose monitoring and dose adaptation is important throughout pregnancy and counselling needs to be established within the programme of pregnancy care for mothers with diabetes. Gestational diabetes develops during pregnancy and may disappear after parturition. The condition of gestational diabetes has received much attention, because there are established treatment options with insulin during pregnancy, which have considerable efficacy in preventing foetal macrosomia,55 in a similar manner as for women with established diabetes prior to pregnancy. The use of human insulin and Insuman formulations during pregnancy has been monitored in pharmacovigilance programmes (periodic safety updates, risk-management plan) and found to be safe.

Use in Paediatrics

The change from animal insulins to recombinant human insulin is well documented in the paediatric population7,16 and is found to be an advantage because the decrease in manifestations of antigenicity is particularly relevant in children. The preference for use in children has been included in guidelines.10 Consistent glucose monitoring is required because of the widely varying dose requirement and distinct changes in insulin requirement during the growth period of children.

The Place of Recombinant Human Insulin in Diabetes Therapy

When considering efficacy, there is clearly an established place for human insulin formulations in the therapy of type 1 (multiple daily injections) and type 2 diabetes. This is clearly addressed in current guidelines.10–12 The need for action is particularly urgent in type 2 diabetes.10 When comparing cost of therapies, recombinant human insulin formulations are the choice for countries in patients with limited resources. In countries with more ample resources, combination therapy is now extensively investigated, e.g. adding glucagon-like peptide 1 agonists or dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors,56,57 and by once-daily injection of prandial insulin.27,56–58

Convenience of using insulins analogue is well established, and there is a certain advantage in reducing hypoglycaemic episodes.24,25,48 The established regiments of basal, premixed and basal-bolus therapy can be implemented with the available range of human insulin formulations when access to insulin analogues and reimbursement are not available.

The essential conditions for improving therapy are glucose monitoring, its frequent implementation, continuing patient education about insulin injection technique42 and how to re-suspend NPH premixed insulins before each injection. Although adherence to recommendations for storage conditions is helpful, there is, however, no difference from the analogue insulins in this respect. In light of worldwide awareness that early implementation of insulin therapy can prevent or delay diabetes complications, access to affordable insulin therapy is the predominant factor when considering recombinant human insulin formulations.

Conclusions

As the burden of diabetes is predicted to increase dramatically in the next decades, the demand of insulin in sufficient amounts and at affordable costs remains a challenge, particularly in developing countries. For that reason, recombinant human insulin formulations are considered to be effective alternatives to insulin analogues in countries with limited healthcare systems and limited resources. Continuing patient education support programmes on disease management and correct use of human insulins are essential (e.g. re-suspension of NPH and premixed formulations, injection technique, adequate storage) for a key role of recombinant human insulins in diabetes treatment. In developing countries, improving access to human insulin can support initiatives for earlier insulin therapy, to improve glycaemic control in the communities, and finally to delay or reduce diabetes complications in the long term.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing assistance for this manuscript was provided by Catherine Amey at Touch Medical Media and was funded by Sanofi US. The contents of this paper and opinions expressed within are those of the authors, and it was the decision of the authors to submit the manuscript for publication. The authors were responsible for the conception of the article and contributed to the writing, including critical review and editing of each draft, and approval of the submitted version.

Funding Statement

Support: The publication of this article was supported by Sanofi US.

References

- 1.Walsh G. Therapeutic insulins and their large-scale manufacture. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;67:151–9. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1809-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chance RE, Frank BH. Research, development, production, and safety of biosynthetic human insulin. Diabetes Care. 1993;16(Suppl. 3):133–42. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.3.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayer JP, Zhang F, DiMarchi RD. Insulin structure and function. Biopolymers. 2007;88:687–713. doi: 10.1002/bip.20734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruttenberg MA. Human insulin: facile synthesis by modification of porcine insulin. Science. 1972;177:623–6. doi: 10.1126/science.177.4049.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obermeier R, Geiger R. A new semisynthesis of human insulin. Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol Chem. 1976;357:759–67. doi: 10.1515/bchm2.1976.357.1.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ladisch MR, Kohlmann KL. Recombinant human insulin. Biotechnol Prog. 1992;8:469–78. doi: 10.1021/bp00018a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brogden RN, Heel RC. Human insulin. A review of its biological activity, pharmacokinetics and therapeutic use. Drugs. 1987;34:350–71. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198734030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Home PD, Thow JC, Tunbridge FK. Insulin treatment: a decade of change. Br Med Bull. 1989;45:92–110. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Everett J, Kerr D. Changing from porcine to human insulin. Drugs. 1994;47:286–96. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199447020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. IDF (2012) International Diabetes Federation Clinical Guidelines Task Force: Global Guideline for Type 2 Diabetes 2012. Available at: http://www.idf.org/sites/default/files/IDF-Guideline-for-Type-2-Diabetes.pdf (accessed 9 July 2015).

- 11.Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB. et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1364–79. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canadian Diabetes Association 2008 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Diabetes in Canada. Can J Diabetes. 2008;32:S1–S201. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandow J, Landgraf W, Becker R, Seipke G. Equivalent recombinant human insulin preparations and their place in therapy. Eur Endocrinology. 2015;11:10–6. doi: 10.17925/EE.2015.11.01.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeLawter DE, Moss JM. Human insulin: a double-blind clinical study of its effectiveness. South Med J. 1985;78:633–5. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198506000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products: Search Insulin. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.SearchAction&SearchType=BasicSearch&searchTerm=insulin (accessed 7 September 2015).

- 16.Mann NP, Johnston DI, Reeves WG, Murphy MA. Human insulin and porcine insulin in the treatment of diabetic children: comparison of metabolic control and insulin antibody production. Br Med J. 1983;287:1580–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.287.6405.1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jovanovic-Peterson L, Kitzmiller JL, Peterson CM. Randomized trial of human versus animal species insulin in diabetic pregnant women: improved glycemic control, not fewer antibodies to insulin, influences birth weight. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:1325–30. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(11)91710-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Markussen J, Damgaard U, Pingel M. et al. Human insulin (Novo): chemistry and characteristics. Diabetes Care. 1983;6(Suppl. 1):4–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pedersen C, Hoegholm A. A comparison of semisynthetic human NPH insulin and porcine NPH insulin in the treatment of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 1987;4:304–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1987.tb00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deckert T. The immunogenicity of new insulins. Diabetes. 1985;34(Suppl. 2):94–6. doi: 10.2337/diab.34.2.s94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Haeften TW. Clinical significance of insulin antibodies in insulin-treated diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 1989;12:641–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.12.9.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lauritano AA, Clements RS Jr, Bell D. Insulin antibodies in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: effect of treatment with semisynthetic human insulin. Clin Ther. 1989;11:268–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schernthaner G. Immunogenicity and allergenic potential of animal and human insulins. Diabetes Care. 1993;16(Suppl. 3):155–65. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.3.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cryer PE, Davis SN, Shamoon H. Hypoglycemia in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1902–12. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.6.1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cryer PE. Hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2010;39:641–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seaquist ER, Anderson J, Childs B. et al. Hypoglycemia and diabetes: a report of a workgroup of the American Diabetes Association and the Endocrine Society. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1384–95. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Owens DR. Stepwise intensification of insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes management-exploring the concept of the basal-plus approach in clinical practice. Diabetic Med. 2013;30:276–88. doi: 10.1111/dme.12019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fletcher JA, Barnett AH, Pyke DA. et al. Transfer from animal insulins to semisynthetic human insulin: a study in four centres. Diabetes Res. 1990;14:151–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davidson JA, Ramirez LC, Raskin P, Selam JL. Transfer of patients with diabetes from semisynthetic human insulin to human insulin prepared by recombinant DNA technology using baker’s yeast: a double-blind, randomized study. Clin Ther. 1991;13:557–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raskin P, Clements RS Jr. The use of human insulin derived from baker’s yeast by recombinant DNA technology. Clin Ther. 1991;13:569–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aronoff S, Goldberg R, Kumar D. et al. Use of a premixed insulin regimen (Novolin 70/30) to replace self-mixed insulin regimens. Clin Ther. 1994;16:41–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beyer J, Enzmann F, Lauerbach M. et al. Treatment with human insulin (recombinant DNA) in diabetic subjects pretreated with pork or beef insulin: first results of a multicenter study. Diabetes Care. 1982;5(Suppl. 2):140–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.5.2.s140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galloway JA, Root MA, Bergstrom R. et al. Clinical pharmacologic studies with human insulin (recombinant DNA) Diabetes Care. 1982;5(Suppl. 2):13–22. doi: 10.2337/diacare.5.2.s13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garber AJ, Davidson JA, Krosnick A. et al. Impact of transfer from animal-source insulins to biosynthetic human insulin (rDNA E coli) in patients with diabetes mellitus. Clin Ther. 1991;13:627–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bell DS, Cutter GR, Lauritano AA. Efficacy of a premixed semisynthetic human insulin regimen. Clin Ther. 1989;11:795–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brodows R, Chessor R. A comparison of premixed insulin preparations in elderly patients. Efficacy of 70/30 and 50/50 human insulin mixtures. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:855–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.6.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. WC500033779 Insuman scientific discussion, updated 2005. Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Scientific_Discussion/human/000201/WC500033779.pdf] (access 9 July 2015).

- 38.Gualandi-Signorini AM, Giorgi G. Insulin formulations – a review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2001;5:73–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Study 1006 (1995). Comparison of the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of HOE31 HGT (biosynthetic human insulin) and HOE31 H (semi-synthetic human insulin) using the euglycaemic clamp technique. Clinical Study report A1 HOE 31 HGT/2/D/111 [data on file].

- 40. Study 302 (1995). Comparison of the efficacy and safety of different biosynthetic and semisynthetic human insulin formulations in a 24-week therapeutic trial. Clinical Study report B1 HOE 36 HGT/2/MN/302/DM [data on file].

- 41. Study 3002 (2000). Comparison of safety and efficacy of recombinant human insulin of Hoechst Marion Roussel and of Eli Lillly in type 2 Diabetic patients requiring insulin treatment (HR1799A/3002). Clinical study report No. F2000CLN0624; 2000, [data on file].

- 42.Kalra S, Balhara YS, Baruah MP. et al. The first Indian recommendations for best practices in insulin injection technique. Indian J Endocr Metab. 2012;16:876–85. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.102929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Study HR1799A-1001 (1997). Comparisons of the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of biosynthetic regular human insulin (Hoechst Marion Roussel) and biosynthetic regular human insulin (Eli Lilly) by using the euglycemic clamp technique. Clinical study report [data on file].

- 44. Study HR1799A-1003 (1997). Comparisons of the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of biosynthetic basal human insulin (Hoechst Marion Roussel) and biosynthetic basal human insulin (Eli Lilly) by using the euglycemic clamp technique. Clinical study report [data on file].

- 45.Jeandidier N, Selam JL, Renard E. et al. Decreased severe hypoglycemia frequency during intraperitoneal insulin infusion using programmable implantable pumps. Evadiac Study Group. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:780. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.7.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Selam JL. External and implantable insulin pumps: current place in the treatment of diabetes. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2001;109(Suppl. 2:):S333–40. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duckworth W, Davis SN. Comparison of insulin glargine and NPH insulin in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a review of clinical studies. J Diab Complications. 2007;21:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yki-Jarvinen H, Ryysy L, Nikkila K. et al. Comparison of bedtime insulin regimens in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:389–96. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-5-199903020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hermanns N, Kulzer B, Kohlmann T. et al. Treatment satisfaction and quality-of-life between type 2 diabetes patients initiating long- vs. intermediate-acting basal insulin therapy in combination with oral hypoglycemic agents – a randomized, prospective, crossover, open clinical trial. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2015;13:77–90. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0279-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cusi K, Cunningham GR, Comstock JP. Safety and efficacy of normalizing fasting glucose with bedtime NPH insulin alone in NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:843–51. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.6.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosenstock J, Schwartz SL, Clark CM Jr. et al. Basal insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes: 28-week comparison of insulin glargine (HOE 901) and NPH insulin. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:631–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Massi Benedetti M, Humburg E, Dressler A, Ziemen M. A one- year, randomised, multicentre trial comparing insulin glargine with NPH insulin in combination with oral agents in patients with type 2 diabetes. Horm Metab Res. 2003;35:189–96. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tschiedel B, Almeida O, Redfearn J, Flacke F. Initial experience and evaluation of reusable insulin pen devices among patients with diabetes in emerging countries. Diabetes Therapy. 2014;5:545–55. doi: 10.1007/s13300-014-0081-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kitzmiller JL, Block JM, Brown FM. et al. Managing preexisting diabetes for pregnancy: summary of evidence and consensus recommendations for care. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1060–79. doi: 10.2337/dc08-9020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Agarwal MM, Punnose J. Recent advances in the treatment of gestational diabetes. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2004;13:1103–11. doi: 10.1517/13543784.13.9.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barnett A, Begg A, Dyson P. et al. Insulin for type 2 diabetes: choosing a second-line insulin regimen. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:1647–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01909.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cefalu WT, Bailey CJ, Bretzel RG. et al. Insulin therapy in people with type 2 diabetes: opportunities and challenges. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:1499–508. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Raccah D, Bretzel RG, Owens D, Riddle M. When basal insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus is not enough—what next? Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2007;23:257–64. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]