Abstract

Crops are regularly exposed to frequent irradiance fluctuations, which decrease their integrated CO2 assimilation and affect their phenotype.

The environment of the natural world in which plants live and have evolved and within which photosynthesis operates is one characterized by change. The time scales over which change occurs can range from seconds (or less) all the way to the geological scale. All of these changes are relevant for understanding plants and the vegetation they create. In this update review, we will focus on how photosynthesis responds to fluctuations in irradiance with time constants up to the range of tens of minutes. Photosynthesis is a highly regulated process, in which photochemistry as well as the electron and proton transport processes leading to the formation of ATP and reducing power (reduced ferredoxin and NADPH) need to be coordinated with the activity of metabolic processes (Foyer and Harbinson, 1994). Light, temperature, the supply of the predominant substrate for photosynthetic metabolism (CO2), and the demand for the products of photosynthetic metabolism are all factors that are involved in short-term alterations of steady-state photosynthetic activity. The coordinated regulation of metabolism with the formation of the metabolic driving forces of ATP and reducing power is subject to various constraints that limit the freedom of response of the system. Of these constraints, the most prominent are the need to limit the rate of formation of active oxygen species by limiting the lifetime of excited states of chlorophyll a and the potential of the driving forces for electron transport (Foyer and Harbinson, 1994; Foyer et al., 2012; Rutherford et al., 2012; Murchie and Harbinson, 2014; Liu and Last, 2017), limiting the decrease of lumen pH to avoid damaging the oxygen evolving complex of PSII (Krieger and Weis, 1993), and adjusting stomatal conductance (gs) to optimize photosynthetic water-use efficiency (Lawson and Blatt, 2014).

The processes that regulate electron and proton transport, enzyme activation, and CO2 diffusion into the chloroplast under steady-state conditions also react in a dynamic and highly concerted manner to changes in irradiance, balancing between light use and photoprotection. This overview of the physiological control underlying dynamic photosynthesis is specific to the C3 photosynthetic pathway. Much less is known about the dynamic regulation of the C4 and Crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) pathways, though given their C3 heritage, we expect that they share much of the regulation of C3 photosynthesis. We note here that in comparison to C3 plants, some C4 species, including maize (Zea mays), show a very slow photosynthetic induction after an irradiance increase (Furbank and Walker, 1985; Chen et al., 2013) and that this phenomenon deserves further attention.

If we grant that the regulation of photosynthesis at steady-state is in some way optimal and represents an ideal balance between light-use efficiency and photoprotection and an ideal balance between CO2 diffusion into the leaf with the loss of water vapor from the leaf, then significance to photosynthesis under a fluctuating irradiance is the loss of optimal regulation. The faster the response to change, the less is the loss of efficiency, whether that be in terms of water use efficiency (WUE) or light use efficiency.

Since its birth one hundred years ago (Osterhout and Haas, 1918), research on the dynamics of photosynthesis and the limitations it produces in a fluctuating irradiance has come a long way (Box 1). While it has been apparent for some time that sunflecks occur in all kinds of canopies (e.g. Pearcy et al., 1990), research on sunfleck photosynthesis was until recently driven by its importance for forest understory shrubs and trees. The ecophysiological importance of sunflecks, photosynthetic responses, and plant growth focused on the importance of these responses for understory plants growing in shade (Pearcy et al., 1996; Way and Pearcy, 2012). Attention has more recently shifted to crop stands grown in full sunlight and the fact that the slow response of photosynthesis to sunflecks is a limitation to crop growth in the field (e.g. Lawson et al., 2012; Carmo-Silva et al., 2015). The importance of improved photosynthesis as a route to improving crop yields (Ort et al., 2015) has given new impetus into better understanding the physiology and the genetics of photosynthetic responses to fluctuating light and improving upon them (e.g. Kromdijk et al., 2016).

FLUCTUATING IRRADIANCE IN CANOPIES

Sunflecks

Most studies have focused on irradiance fluctuations at the bottom of canopies or in forest understories. In these situations, a shade environment with little diurnal variation prevails, and most incoming irradiance arrives due to transmission and scattering by leaves higher up in the canopy. Also, gaps in the canopy, which move in response to wind, allow brief but significant increases in irradiance (Pearcy, 1990). Smith and Berry (2013) proposed a detailed classification of these fluctuations, resulting in the terms sunfleck (<8 min and peak irradiance lower than above-canopy irradiance), sun patch (>8 min), sun gap (>60 min), and clearing (>120 min).

In addition to the length of the fluctuation, classifying a fluctuation as a sunfleck depends on the irradiance increasing above a specific threshold during the fluctuation. Often, fixed thresholds are used, but their values vary greatly (60–300 µmol m−2 s−1; Pearcy, 1983, 1990; Tang et al., 1988; Roden and Pearcy, 1993; Barradas et al., 1998; Naumburg and Ellsworth, 2002). Thresholds may be adjusted depending on canopy structure, position within the canopy where measurements are taken, and angle of measurement (Pearcy, 1990; Barradas et al., 1998). An alternative approach is to use the fraction of irradiance transmitted by the canopy instead of absolute irradiance to calculate the threshold (Barradas et al., 1998). However, this approach requires an additional measurement of irradiance above the canopy.

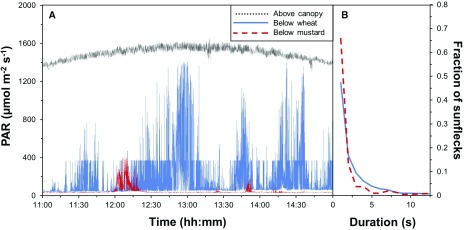

Short-lived sunflecks with low peak irradiance are particularly abundant in the lower layers of canopies and forest understories. Pearcy et al. (1990) reported that 79% of sunflecks were ≤1.6 s long in a soybean (Glycine max) canopy, and the same distribution was reported for aspen (Populus tremuloides; Roden and Pearcy, 1993). Peressotti et al. (2001) reported that most sunflecks in wheat (Triticum aestivum), maize, and sunflower (Helianthus annuus) were ≤1 s long. Most sunflecks in bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) and rice (Oryza sativa) canopies were ≤5.0 s long (Barradas et al., 1998; Nishimura et al., 1998). These results agree with our measurements in durum wheat (Triticum durum) and white mustard (Sinapis alba; Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Sunflecks in two crop canopies. A, Irradiance fluctuations above and below a durum wheat and white mustard canopy, logged at 1 s resolution. B, Fraction of the total number of sunflecks as a function of sunfleck duration; calculations based on data displayed in A. Photosynthetically active irradiance (PAR; 400–700 nm) was logged using two LI-190R quantum sensors (Li-Cor Biosciences) and an LI-1400 (Li-Cor) data logger. Data were recorded 10 cm above the ground for measurements below canopies and just above canopies for 6 h (11:00–17:00) on two consecutive days (May 26 and 27, 2017) in Wageningen, The Netherlands (51.97 °N, 5.67 °E, 12 m above sea level). The two days were cloudless with average wind speeds of 3.5 m s−1 and 4.2 m s−1, respectively. In the absence of sunflecks, the irradiance measured below the canopy was 2.4% and 3.7% of above-canopy PAR for white mustard and wheat, respectively, indicating full canopy closure. To detect sunflecks, a baseline was constructed by interpolating PAR values in the absence of sunflecks and defining a sunfleck as the absolute change in PAR with respect to the baseline >10 µmol m−2 s−1 (this was larger than the measurement error).

Canopy structure is assumed to affect sunfleck distribution (Pearcy, 1990), but this has so far only been systematically tested by Peressotti et al. (2001), who compared sunflecks in different crop canopies and found only small differences between wheat, maize, and sunflower. Our data, on the other hand, revealed bigger differences between crops despite similar meteorological conditions (Fig. 1): in durum wheat, 2,606 sunflecks (83% of total irradiance) were detected within 6 h, while only 213 (22%) were observed in white mustard (Fig. 1A). In white mustard, sunflecks tended to be shorter and weaker, though for both crops most sunflecks were <5 s long (Fig. 1B). For most sunflecks, the average irradiance increase was <350 µmol m−2 s−1, and peak irradiance was always below the irradiance measured above the canopy (Fig. 1A). However, a large proportion of short sunflecks may not always contribute much to integrated irradiance, partly because of their short duration and partly because of their low peak irradiance (Pearcy, 1990). For example, in a soybean canopy, the peak irradiance in sunflecks less than 1.6 s long was two to three times less than that of longer sunflecks, and contributed only 6.7% of the total irradiance, while sunflecks lasting up to 10 s contributed only 33% of the total irradiance (Pearcy et al., 1990).

Sunflecks can also be caused by the penumbra effect (Smith et al., 1989), a “soft shadow” that occurs when a light source is partially blocked. In canopies, a penumbra is produced by small canopy elements that partially obscure the solar disc as viewed from a lower leaf. When combined with rapid leaf movements, the penumbra causes sunflecks on leaves that are otherwise shaded. Due to the penumbra effect, it was estimated that a gap in a canopy must have an angular size greater than 0.5° in order for the sunfleck to reach full solar irradiance (Pearcy, 1990). The frequent, short sunflecks discussed above are probably caused by penumbra (Smith and Berry, 2013) and contribute to a substantial fraction of total irradiance in forest understories (Pearcy, 1990).

Due to wind-induced movements, the structure of canopies is not static. Wind has two effects: (1) movement of the whole plant or “swaying” (de Langre, 2008; Tadrist et al., 2014; Burgess et al., 2016) and (2) fluttering of single leaves, especially in trees (Roden and Pearcy, 1993; Roden, 2003; de Langre, 2008). Plant swaying alters the spatial distribution of canopy gaps and the exposure of leaves to these gaps, adding sunflecks and shadeflecks to the baseline irradiance that would occur in the absence of wind. Fluttering allows individual leaves to have a more uniform diurnal distribution of absorbed irradiance and to maintain a high photosynthetic induction state (Roden, 2003). Fluttering further increases the number of sunflecks at the bottom of the canopy (Roden and Pearcy, 1993). Leaves flutter at a wide frequency range (1–100 Hz; Roden and Pearcy, 1993; Roden, 2003; de Langre, 2008), whereas plant swaying occurs at 0.1 to 10 Hz (de Langre, 2008; Burgess et al., 2016). Wind thus introduces rapid irradiance fluctuations in the entire canopy. Without wind, sunflecks and shadeflecks can still be caused by gaps in the canopy structure and by penumbra, but high wind speeds have been correlated with increasing irradiance fluctuations (Tang et al., 1988).

Shadeflecks

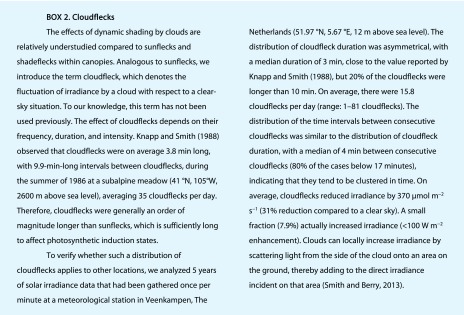

As long as the total irradiance intercepted by a canopy remains the same, the existence of sunflecks necessitates the existence of shadeflecks (i.e. transient excursions below a baseline that is the average irradiance (Pearcy, 1990; Pearcy et al., 1990; Barradas et al., 1998; Lawson et al., 2012). It is important to distinguish between sunflecks and shadeflecks, as the dynamic responses of photosynthesis are different for increasing and decreasing irradiance and involve different potentially limiting processes (see below). A shadefleck should not be seen as a “period between sunflecks,” but rather as a brief period of low irradiance with respect to a baseline of intermediate or high irradiance, which tends to occur in the top and middle layers of a canopy. A special type of shadefleck is a cloudfleck (Box 2; Knapp and Smith, 1988).

THE REGULATION OF PHOTOSYNTHESIS IN FLUCTUATING IRRADIANCE

Responses and Regulation of Electron and Proton Transport

The shorter term physiological responses of photosynthesis begin with light-driven redox state and pH changes occurring within and close to the thylakoid membranes. Photochemistry, the primary chemical event of photosynthesis, provides the redox driving forces for electron and proton transport, which result in the feed-forward activation of metabolic processes that produce CO2 assimilation. Metabolism, when limiting, will down-regulate electron transport via feed-back mechanisms. This balance between feed-forward and feed-back regulation is at the heart of photosynthetic regulation, including responses to changing irradiance.

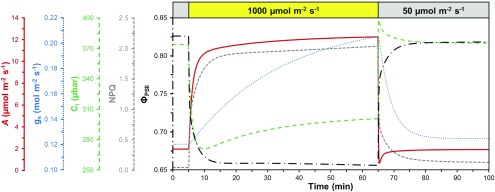

In a leaf initially subject to a subsaturating irradiance, a sudden increase in irradiance results in an increase in the rate of photochemistry and then an increase in the rate of linear electron flow (LEF) from water to ferredoxin within milliseconds. For every electron passing along the LEF, three protons are translocated from the stroma into the thylakoid lumen, which changes the electric (Δψ) and pH (ΔpH) gradients across the thylakoid membrane. Together, Δψ and ΔpH constitute the proton motive force (pmf). The pmf is further modulated by cyclic electron flux around PSI (Strand et al., 2015; Shikanai and Yamamoto, 2017) and alternative noncyclic electron flux (Asada, 2000; Bloom et al., 2002), making the pmf more flexible to changing metabolic demands for ATP and NADPH (Kramer and Evans, 2011) and adjustments in lumen pH resulting in regulatory responses of thylakoid electron transport and nonphotochemical quenching (NPQ). The acidification of the lumen upon increases in irradiance partially drives the fastest component of NPQ (Fig. 2), qE. This form of NPQ acts to reduce the lifetime of excited singlet states of chlorophyll a (1chl*) in PSII. When the rate of PSII excitation and 1chl* formation exceeds the potential for photochemical dissipation of 1chl* via electron transport (e.g. during irradiance increases), the lifetime of 1chl* in PSII tends to increase, potentially increasing the rate of formation of triplet chlorophylls in the PSII pigment bed and reaction center, resulting in the formation of reactive singlet oxygen (Müller et al., 2001). Up-regulating NPQ activity counteracts the tendency for increased 1chl* lifetime and moderates the increase in singlet oxygen formation (Müller et al., 2001). The protein PsbS senses the low pH in the lumen (Li et al., 2000, 2002) and may mediate conformational changes in trimeric light harvesting complex II (LHCII) antenna complexes that allow the light harvesting complex (LHC) to more efficiently dissipate excitons formed in PSII as heat (Ruban, 2016). The presence of the carotenoid zeaxanthin further amplifies qE (Niyogi et al., 1998). Zeaxanthin is formed from violaxanthin via antheraxanthin by the enzyme violaxanthin de-epoxidase upon acidification of the thylakoid lumen and is reconverted to violaxanthin as lumen pH increases (Demmig-Adams, 1990).

Figure 2.

Schematic depiction of dynamic reactions of leaf photosynthetic processes to irradiance fluctuations. The leaf is initially adapted to shade (50 µmol m−2 s−1), then exposed to strong irradiance (1,000 µmol m−2 s−1) for 60 min, after which it is shaded again for 35 min. Displayed are net photosynthesis rate (A; red line, continuous), stomatal conductance (gs; blue line, dots), substomatal CO2 partial pressure (Ci; green line, long dashes), nonphotochemical quenching (NPQ; gray line, short dashes), and the electron transport efficiency of PSII (ΦPSII; black line, long dashes and dots). These values are representative of Arabidopsis Col-0, grown in climate chambers at a constant irradiance of 170 µmol m−2 s−1.

Since after drops in irradiance NPQ relaxes only slowly (Fig. 2), LEF is transiently limited by an overprotected and quenched PSII, potentially limiting photosynthesis (Zhu et al., 2004). In Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), the ΔpH component of the pmf was increased in plants overexpressing K+ efflux antiporter proteins, accelerating NPQ induction and relaxation kinetics and diminishing transient reductions in LEF and CO2 assimilation upon transitions from high to low irradiance (Armbruster et al., 2014). In tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), the simultaneous overexpression of PsbS, violaxanthin de-epoxidase and zeaxanthin epoxidase increased the rate of NPQ relaxation, which subsequently increased growth in the field by 14% to 20% (Kromdijk et al., 2016). These results prove that slow NPQ relaxation is an important limitation in naturally fluctuating irradiance. Further, the results of Kromdijk et al. (2016) are a powerful testament to the fact that irradiance fluctuations strongly diminish growth in the field; they provide a glimpse into growth accelerations that would be possible if the rate constants of other processes responding to fluctuating irradiance were enhanced.

Chloroplast Movement

Another potential limitation to electron transport under fluctuating irradiance is the movement of chloroplasts in response to blue irradiance. At high blue irradiance, chloroplasts move toward the anticlinal walls of the mesophyll cells, while at low blue irradiance, they move to the periclinal walls (Haupt and Scheuerlein, 1990), resulting in decreases and increases of absorptance, respectively (Gorton et al., 2003; Williams et al., 2003; Tholen et al., 2008; Loreto et al., 2009). In leaves of some species, chloroplast movements can change irradiance absorptance by >10%, although in other species the effect is <1% (Davis et al., 2011). The reduction in absorptance in high irradiance has a photoprotective effect, and significant reductions in photoinhibition have been demonstrated for Arabidopsis (Kasahara et al., 2002; Davis and Hangarter, 2012). Furthermore, chloroplast movements alter the area of chloroplasts exposed to the intercellular spaces, changing mesophyll conductance (gm). Importantly, chloroplasts move within minutes (Brugnoli and Björkman, 1992; Dutta et al., 2015; Łabuz et al., 2015), so the effects of their movement on absorptance and gm (Box 3) should be relevant under naturally fluctuating irradiance. In particular, slow chloroplast movement toward the low irradiance position (time constants of 6–12 min; Davis and Hangarter, 2012; Łabuz et al., 2015), which lead to increased absorptance, would transiently decrease absorptance after drops in irradiance, thus limiting electron transport and photosynthesis (i.e. similar to the effect of slow qE relaxation, see above). However, experimental evidence of this possible limitation is currently lacking.

Enzyme Activation and Metabolite Turnover

The activity of several key enzymes in the Calvin Benson cycle (CBC) is regulated in an irradiance-dependent manner, much of which depends on the thioredoxin (TRX) system (Geigenberger et al., 2017). There is a multitude of TRX types and isoforms. For example, Arabidopsis chloroplasts contain 10 different TRX isoforms (Michelet et al., 2013). Chloroplastic TRXs may be reduced by ferredoxin-dependent or NADPH-dependent thioredoxin reductases (Nikkanen et al., 2016; Thormählen et al., 2017). In the chloroplast, f-type TRXs control the activation state of Fru-1,6-bisphosphatase (FBPase), sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase (SBPase), and Rubisco activase (Rca; Michelet et al., 2013; Naranjo et al., 2016). While oxidized FBPase maintains a basal activity of 20% to 30%, the oxidized form of SBPase is completely inactive (Michelet et al., 2013). In Pisum sativum, the activities of phosphoribulokinase (PRK) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase are controlled by the redox-regulated protein CP12, which binds the enzymes together in low irradiance and thereby inactivates them even if they are reduced (i.e. active; Howard et al., 2008). However, this type of regulation by CP12 is not universal, as in several species, the complex formed by CP12, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, and PRK was mostly absent in darkness or the enzymes existed both in the bound and free form (Howard et al., 2011). Apart from the action of CP12, PRK activity is also regulated by TRX m and f (Schürmann and Buchanan, 2008).

Within the first minute after a switch from low to high irradiance, SBPase, FBPase, and PRK are believed to limit photosynthesis via the slow regeneration of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP; Sassenrath-Cole and Pearcy, 1992, 1994; Sassenrath-Cole et al., 1994; Pearcy et al., 1996). These enzymes activate and deactivate quickly, with time constants (τ) of ∼1 to 3 min for activation and ∼2 to 4 min for deactivation (Supplemental Table S1). Compared to limitation by either Rubisco or gs (see below), which often (co)-limit photosynthetic induction for 10 to 60 min, the limitation due to activation of SBPase, FBPase, and PRK appears negligible but is relatively understudied. Due to their relatively quick deactivation in low irradiance, it may be that in the field the activation states of these enzymes are a stronger limitation of CO2 assimilation than Rubisco or gs (Pearcy et al., 1996), as the majority of sunflecks in canopies are short and narrowly spaced (see above). More research into this potentially large limitation is needed, e.g. by using plants with increased concentrations of CBC enzymes (e.g. Simkin et al., 2015), as well as “always-active” FBPase and PRK (Nikkanen et al., 2016).

The dependence of the activation state of Rubisco upon irradiance resembles that of an irradiance response curve of photosynthesis (Lan et al., 1992). In low irradiance, 30% to 50% of the total pool of Rubisco is active (Pearcy, 1988; Lan et al., 1992; Carmo-Silva and Salvucci, 2013). The remainder is activated with a τ of 3 to 5 min after switching to high irradiance (Pearcy, 1988; Woodrow and Mott, 1989; Kaiser et al., 2016; Taylor and Long, 2017). Activation of Rubisco active sites requires the binding of Mg2+ and CO2 to form a catalytically competent (carbamylated) enzyme, after which RuBP and another CO2 or O2 molecule have to bind for either carboxylation or oxygenation to occur (Tcherkez, 2013). Rubisco activates more quickly at higher CO2 partial pressures, both in folio (Kaiser et al., 2017) and in vitro (Woodrow et al., 1996), a phenomenon that is not well understood and whose kinetics cannot be explained by carbamylation.

Several types of sugar phosphates can bind to Rubisco catalytic sites and block their complete activation (Bracher et al., 2017). Removal of these inhibitors requires the action of Rca (Salvucci et al., 1985), whose activity depends on thioredoxin and ATP. Rca light-activates with a τ of ∼4 min in spinach (Spinacia oleracea; Lan et al., 1992). In Arabidopsis, Rca is present in two isoforms, of which the larger, α-isoform is redox regulated and the smaller, β-isoform is regulated by the α-isoform (Zhang and Portis, 1999; Zhang et al., 2002). In transgenic plants only containing the β-isoform, photosynthetic induction after a transition from low to high irradiance was faster than in the wild type, as Rca activity was constitutively high and independent of irradiance (Carmo-Silva and Salvucci, 2013; Kaiser et al., 2016). Modifying the composition of Rca (Prins et al., 2016) or its concentration, either transgenically (Yamori et al., 2012) or through classical breeding (Martínez-Barajas et al., 1997), might enhance photosynthesis and growth in fluctuating irradiance (Carmo-Silva et al., 2015).

After the fixation of CO2 into RuBP, the triose phosphates may be transported out of the chloroplast and converted into sugars, after which the phosphate is transported back into the chloroplast and recycled via the chloroplast ATPase and the CBC (Stitt et al., 2010). The enzyme Suc phosphate synthase can transiently limit photosynthesis after a transition from low to high irradiance, but this has so far only been shown in elevated CO2 (Stitt and Grosse, 1988). After decreases in irradiance, pools of CBC intermediates can transiently enhance photosynthesis (“postillumination CO2 fixation”), while the turnover of Gly in the photorespiratory pathway may be visible as a transient decrease in photosynthesis (“postillumination CO2 burst”). After very short (≤1 s) sunflecks, postillumination CO2 fixation enhances total sunfleck carbon gain greatly, such that the CO2 fixed directly after a sunfleck exceeds the CO2 fixed during the sunfleck (Pons and Pearcy, 1992). The negative effect of postillumination CO2 fixation on the carbon balance of a sunfleck seems less pronounced in comparison (Leakey et al., 2002). For more details on both phenomena, see Kaiser et al. (2015).

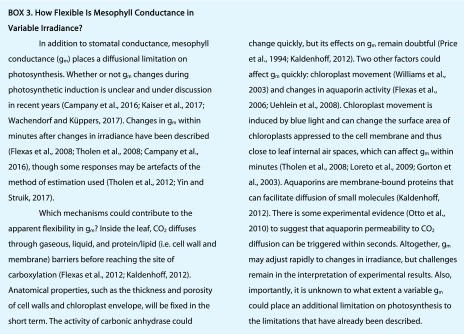

CO2 Diffusion into the Chloroplast

Diffusion of CO2 to the site of carboxylation is mediated by gs and gm. Stomata tend to decrease their aperture in low irradiance, when evaporative demand and demand for CO2 diffusion are small. Vast differences exist between species (15- to 25-fold) for steady-state gs in low and high irradiance (e.g. McAusland et al., 2016), for rates of stomatal opening after irradiance increases (τ = 4–29 min) and for rates of stomatal closure after irradiance decreases (τ = 6–18 min; Vico et al., 2011). Often, initial gs after a switch from low to high irradiance is small enough, and stomatal opening is slow enough (Fig. 2), to transiently limit photosynthesis (McAusland et al., 2016; Wachendorf and Küppers, 2017). Manipulating gs to respond more quickly to irradiance could greatly enhance photosynthesis and WUE in fluctuating irradiance (Lawson and Blatt, 2014; Vialet-Chabrand et al., 2017b). Mesophyll conductance will further affect the CO2 available for photosynthesis (Tholen et al., 2012; Yin and Struik, 2017), and steady-state gm affects CO2 diffusion as strongly as does gs (Flexas et al., 2008, 2012). Mesophyll conductance may be variable under fluctuating irradiance (Campany et al., 2016), as some of the processes determining gm are flexible (Price et al., 1994; Flexas et al., 2006; Uehlein et al., 2008; Otto et al., 2010; Kaldenhoff, 2012). The possibility that transient gm changes limit photosynthesis in fluctuating irradiance is discussed in Box 3.

Limiting CO2 diffusion into the chloroplast after a switch from low to high irradiance may transiently limit photosynthesis in two ways: via a transiently low availability of the substrate CO2 for carboxylation and by decreasing the rate of Rubisco activation (Mott and Woodrow, 1993). While the former limitation is visible through a concomitant increase in A and chloroplast CO2 partial pressure (Cc) along the steady-state A/Cc relationship (Küppers and Schneider, 1993), the latter can be calculated by log-linearizing CO2 assimilation after an increase in irradiance, after correcting for changes in Ci (Woodrow and Mott, 1989). The apparent τ for Rubisco activation calculated from gas exchange in folio correlates well with Rubisco activation in vitro (Woodrow and Mott, 1989; Hammond et al., 1998) and with Rca concentrations (Mott and Woodrow, 2000; Yamori et al., 2012). Additionally, Rubisco activation during photosynthetic induction can be approximated by “dynamic A/Ci curves” which are achieved by measuring the rate of photosynthetic induction at several Ci levels and plotting maximum rates of carboxylation (Vcmax) as a function of time (Soleh et al., 2016). It was recently shown that the apparent τRubisco derived from dynamic A/Ci curves was in agreement with values derived using the procedure described by Woodrow and Mott (1989) and Taylor and Long (2017). Apparent τRubisco decreases with increases in Ci (Mott and Woodrow, 1993; Woodrow et al., 1996) and with relative air humidity (Kaiser et al., 2017) during photosynthetic induction. The latter phenomenon was caused by humidity effects in initial gs, leading to faster depletion of Cc and transiently lower Cc after an increase in irradiance (Kaiser et al., 2017). The mechanism behind this slowing down of Rubisco activation due to lower Cc is as yet unresolved.

PHENOTYPING FOR FASTER PHOTOSYNTHESIS IN FLUCTUATING IRRADIANCE

High-throughput phenotyping for natural variation (including mutant screens, e.g. Cruz et al., 2016) gained importance following the analyses of Lawson et al. (2012), Lawson and Blatt (2014), and Long et al. (2006). These studies highlighted the response times of photosynthesis to changing irradiance as limitations to carbon gain, including the slow response of gs (Tinoco-Ojanguren and Pearcy, 1993), which can also diminish WUE (Lawson and Blatt, 2014), stressing their value as routes for improving assimilation. Kromdijk et al. (2016) consequently showed that improved relaxation of qE type NPQ improved tobacco yield under field conditions. While they used transgenics, the modifications used—increased amounts of PsbS, violaxanthin de-epoxidase and zeaxanthin epoxidase—could have occurred naturally. In fact, altering gene expression patterns has been a major route to improving the usefulness of plants for agriculture (Swinnen et al., 2016), either through natural variation in the gene pool of natural ancestors or through mutations occurring during domestication. Naturally occurring variation in a trait can be used to analyze the genetic architecture of the trait, and this can be used to increase the efficiency of improving the trait by breeding. Knowing how a trait is genetically determined increases the options for its improvements by breeding beyond those emerging from the physiological or biochemical approaches of the kind used by Kromdijk et al. (2016). Variation for the kinetics of photosynthetic responses to changing irradiance is also another resource for further conventional physiological and biochemical analyses of the regulation and limitations acting on photosynthesis under these conditions.

If variation for a quantitative trait, such as photosynthetic responses, is identified in a genetically diverse population, and the genetic diversity has been mapped by means of e.g. single nucleotide polymorphisms, it is possible to correlate genetic with phenotypic variation (e.g. Harbinson et al., 2012; Rungrat et al., 2016) and to identify the QTL (quantitative trait loci) whose variation correlates with phenotypic variation. Different types of mapping populations can be used for QTL identification: genome-wide association study and linkage mapping using recombinant inbred lines (RIL). These strategies have their own advantages and disadvantages (Bergelson and Roux, 2010; Harbinson et al., 2012; Korte and Farlow, 2013; Rungrat et al., 2016). Once identified, QTL are invaluable as markers for conventional plant breeding approaches and as a starting point for identifying the causal gene for the QTL. It is obviously advantageous to maximize the chances of finding an association by including as much genetic diversity as possible in a mapping population. In the case of crop plants, domestication results in a loss of genetic diversity (Doebley et al., 2006; Shi and Lai, 2015), so there is much to be gained by including field races and wild types in the construction of mapping populations or RILs. The phenotypic data required for QTL mapping requires measurements upon hundreds or thousands of individuals depending on the mapping approach adopted, the precision of the phenotyping procedure compared to the variability of the trait, and the heritability of the trait. In photosynthesis, which even in stable environments can change diurnally, quick measurements are needed (Flood et al., 2016). Measuring this many plants quickly places considerable demands on the design of high-throughput systems. Currently, the measuring technologies that are best suited to automated high-throughput phenotyping of plant photosynthetic traits, including those in unstable irradiance, are chlorophyll fluorescence imaging (Barbagallo et al., 2003; Furbank and Tester, 2011; Harbinson et al., 2012; Rungrat et al., 2016) and thermal imaging for measuring stomatal responses (Jones, 1999; Furbank and Tester, 2011; McAusland et al., 2013). While it is based on fluorescence from PSII, chlorophyll fluorescence allows the measurement of many useful photosynthetic parameters such as the electron transport efficiency of PSII, NPQ, and its components (of which qE is most commonly reported), Fv/Fm, qP, Fv′/Fm′, and similar parameters (Baker et al., 2007; Furbank and Tester, 2011; Harbinson et al., 2012; Murchie and Harbinson, 2014). Chlorophyll fluorescence procedures are well developed, and the phenomenology and correlations of fluorescence-derived physiological parameters are well understood (e.g. Baker et al., 2007; Baker, 2008; Murchie and Harbinson, 2014). Biomass accumulation can also be used as a measure of plant fitness, and while this is not high-throughput nor specific for a photosynthetic process, it is simple to apply, requires no specific technology, and gives a useful measure of the extent to which a plant can successfully adapt to fluctuating irradiance.

While the technologies and procedures for phenotyping and QTL identification are promising, the application of this approach to photosynthesis is still limited, especially in the case of photosynthetic responses to fluctuating irradiance. QTL for qE have been identified using low throughput phenotyping (Jung and Niyogi, 2009). van Rooijen et al. (2017) have identified a gene (YS1) underlying longer-term responses to an irradiance change using a genome-wide association study analysis of an Arabidopsis mapping population (Li et al., 2010). This work demonstrates that phenotyping combined with further genetic analysis can be used for identifying QTLs and genes linked to variation in a photosynthetic trait, opening the door to a new approach to understanding photosynthetic responses to fluctuating irradiance. If a QTL can be found for a trait, such as faster responses to fluctuating light, then by implication there is an association with genetic markers. This association can be used in marker-assisted breeding to accelerate the transfer of the QTL into a genotype that lacks the trait but has otherwise desirable properties.

CONCLUSION

Average rates of photosynthesis decrease under fluctuating irradiance when compared to a constant environment. Whereas part of this decrease is explained by the nonlinear response of photosynthesis to irradiance, further decreases are the result of slow changes in enzyme activities, stomatal conductance, and NPQ. Changes in mesophyll conductance and irradiance absorbance (caused by chloroplast movements) may add to these limitations, but this awaits experimental verification. Whereas much of the earlier research focused on Rubisco activity and dynamic stomatal conductance, recent experimental and modeling studies suggest other processes (and enzymes) to be limiting (Hou et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2016). Therefore, both models and experiments should widen their scope. This requires extending the toolbox of the dynamic photosynthesis experimentalist to include rapid gas exchange systems, chlorophyll fluorescence, and spectroscopic techniques and the design of new measurement protocols and mathematical models to provide the necessary parameters. There is also the realization that the growth environment of plants should approximate that experienced in the field (Poorter et al., 2016). Recent developments of lighting technology (LEDs) enable this. Increasingly, plants are grown under more fluctuating conditions (Külheim et al., 2002; Leakey et al., 2003; Athanasiou et al., 2010; Alter et al., 2012; Vialet-Chabrand et al., 2017a), but the complex nature of natural irradiance fluctuations and the scarcity of measurements in the field mean that to date no standard exists for defining relevant fluctuating growth conditions in the laboratory.

Our review of the literature indicates that the fluctuating regime strongly depends on whether fluctuations are caused by wind and gaps in the canopy (i.e. sunflecks) or by intermittent cloudiness (i.e. cloudflecks; Box 2). Whereas the former consists of fluctuations at the scale of seconds over a low irradiance background, cloudflecks are fluctuations at the scale of minutes over a high irradiance background. Furthermore, the variation across species, canopy structure, and location seems to be small, but further characterization of cloudflecks and sunflecks is needed. Both fluctuating regimes are relevant to crops in the field, but the relative importance of processes limiting photosynthesis could depend on the specific irradiance pattern.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Table S1. Time constants of irradiance-dependent activation and deactivation of FBPase, PRK, and SBPase, based on fits to published data.

Footnotes

Much of the work leading up to this review was performed under the Dutch national program “Biosolar Cells.” During the elaboration of this review, A.M. was financed by the research program “Crop sciences: improved tolerance to heat and drought” with project number 867.15.030 by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research. J.H. would like to acknowledge financial support from the EU Marie Curie ITN “Harvest” (grant 238017).

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Alter P, Dreissen A, Luo FL, Matsubara S (2012) Acclimatory responses of Arabidopsis to fluctuating light environment: comparison of different sunfleck regimes and accessions. Photosynth Res 113: 221–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster U, Carrillo LR, Venema K, Pavlovic L, Schmidtmann E, Kornfeld A, Jahns P, Berry JA, Kramer DM, Jonikas MC (2014) Ion antiport accelerates photosynthetic acclimation in fluctuating light environments. Nat Commun 5: 5439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asada K. (2000) The water-water cycle as alternative photon and electron sinks. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 355: 1419–1431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athanasiou K, Dyson BC, Webster RE, Johnson GN (2010) Dynamic acclimation of photosynthesis increases plant fitness in changing environments. Plant Physiol 152: 366–373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker NR. (2008) Chlorophyll fluorescence: a probe of photosynthesis in vivo. Annu Rev Plant Biol 59: 89–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker NR, Harbinson J, Kramer DM (2007) Determining the limitations and regulation of photosynthetic energy transduction in leaves. Plant Cell Environ 30: 1107–1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbagallo RP, Oxborough K, Pallett KE, Baker NR (2003) Rapid, noninvasive screening for perturbations of metabolism and plant growth using chlorophyll fluorescence imaging. Plant Physiol 132: 485–493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barradas VL, Jones HG, Clark JA (1998) Sunfleck dynamics and canopy structure in a Phaseolus vulgaris L. canopy. Int J Biometeorol 42: 34–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergelson J, Roux F (2010) Towards identifying genes underlying ecologically relevant traits in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Rev Genet 11: 867–879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom AJ, Smart DR, Nguyen DT, Searles PS (2002) Nitrogen assimilation and growth of wheat under elevated carbon dioxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 1730–1735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracher A, Whitney SM, Hartl FU, Hayer-Hartl M (2017) Biogenesis and metabolic maintenance of Rubisco. Annu Rev Plant Biol 68: 29–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugnoli E, Björkman O (1992) Chloroplast movements in leaves: influence on chlorophyll fluorescence and measurements of light-induced absorbance changes related to ΔpH and zeaxanthin formation. Photosynth Res 32: 23–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess AJ, Retkute R, Preston SP, Jensen OE, Pound MP, Pridmore TP, Murchie EH (2016) The 4-dimensional plant: effects of wind-induced canopy movement on light fluctuations and photosynthesis. Front Plant Sci 7: 1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campany CE, Tjoelker MG, von Caemmerer S, Duursma RA (2016) Coupled response of stomatal and mesophyll conductance to light enhances photosynthesis of shade leaves under sunflecks. Plant Cell Environ 39: 2762–2773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmo-Silva AE, Salvucci ME (2013) The regulatory properties of Rubisco activase differ among species and affect photosynthetic induction during light transitions. Plant Physiol 161: 1645–1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmo-Silva E, Scales JC, Madgwick PJ, Parry MAJ (2015) Optimizing Rubisco and its regulation for greater resource use efficiency. Plant Cell Environ 38: 1817–1832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JW, Yang ZQ, Zhou P, Hai MR, Tang TX, Liang YL, An TX (2013) Biomass accumulation and partitioning, photosynthesis, and photosynthetic induction in field-grown maize (Zea mays L.) under low- and high-nitrogen conditions. Acta Physiol Plant 35: 95–105 [Google Scholar]

- Cruz JA, Savage LJ, Zegarac R, Hall CC, Satoh-Cruz M, Davis GA, Kovac WK, Chen J, Kramer DM (2016) Dynamic environmental photosynthetic imaging reveals emergent phenotypes. Cell Syst 2: 365–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis PA, Caylor S, Whippo CW, Hangarter RP (2011) Changes in leaf optical properties associated with light-dependent chloroplast movements. Plant Cell Environ 34: 2047–2059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis PA, Hangarter RP (2012) Chloroplast movement provides photoprotection to plants by redistributing PSII damage within leaves. Photosynth Res 112: 153–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Langre E. (2008) Effects of wind on plants. Annu Rev Fluid Mech 40: 141–168 [Google Scholar]

- Demmig-Adams B. (1990) Carotenoids and photoprotection in plants: a role for the xanthophyll zeaxanthin. Biochim Biophys Acta 1020: 1–24 [Google Scholar]

- Doebley JF, Gaut BS, Smith BD (2006) The molecular genetics of crop domestication. Cell 127: 1309–1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta S, Cruz JA, Jiao Y, Chen J, Kramer DM, Osteryoung KW (2015) Non-invasive, whole-plant imaging of chloroplast movement and chlorophyll fluorescence reveals photosynthetic phenotypes independent of chloroplast photorelocation defects in chloroplast division mutants. Plant J 84: 428–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Barbour MM, Brendel O, Cabrera HM, Carriquí M, Díaz-Espejo A, Douthe C, Dreyer E, Ferrio JP, Gago J, et al. (2012) Mesophyll diffusion conductance to CO2: an unappreciated central player in photosynthesis. Plant Sci 193-194: 70–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Ribas-Carbó M, Diaz-Espejo A, Galmés J, Medrano H (2008) Mesophyll conductance to CO2: current knowledge and future prospects. Plant Cell Environ 31: 602–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Ribas-Carbó M, Hanson DT, Bota J, Otto B, Cifre J, McDowell N, Medrano H, Kaldenhoff R (2006) Tobacco aquaporin NtAQP1 is involved in mesophyll conductance to CO2 in vivo. Plant J 48: 427–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood PJ, Kruijer W, Schnabel SK, van der Schoor R, Jalink H, Snel JFH, Harbinson J, Aarts MGM (2016) Phenomics for photosynthesis, growth and reflectance in Arabidopsis thaliana reveals circadian and long-term fluctuations in heritability. Plant Methods 12: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foyer CH, Harbinson J (1994) Oxygen metabolism and the regulation of photosynthetic electron transport. In Foyer CH, Mullineaux P, eds, Causes of Photooxidative Stress and Amelioration of Defense Systems in Plants. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp 1–42 [Google Scholar]

- Foyer CH, Neukermans J, Queval G, Noctor G, Harbinson J (2012) Photosynthetic control of electron transport and the regulation of gene expression. J Exp Bot 63: 1637–1661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furbank RT, Tester M (2011) Phenomics—technologies to relieve the phenotyping bottleneck. Trends Plant Sci 16: 635–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furbank RT, Walker DA (1985) Photosynthetic induction in C4 leaves: an investigation using infra-red gas analysis and chlorophyll a fluorescence. Planta 163: 75–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geigenberger P, Thormählen I, Daloso DM, Fernie AR (2017) The unprecedented versatility of the plant thioredoxin system. Trends Plant Sci 22: 249–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorton HL, Herbert SK, Vogelmann TC (2003) Photoacoustic analysis indicates that chloroplast movement does not alter liquid-phase CO2 diffusion in leaves of Alocasia brisbanensis. Plant Physiol 132: 1529–1539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z, Wang F, Xiang X, Ahammed GJ, Wang M, Onac E, Zhou J, Xia X, Shi K, Yin X, et al. (2016) Systemic induction of photosynthesis via illumination of the shoot apex is mediated sequentially by phytochrome B, auxin and hydrogen perodixe in tomato. Plant Physiol 172: 1259–1272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond ET, Andrews TJ, Mott KA, Woodrow IE (1998) Regulation of Rubisco activation in antisense plants of tobacco containing reduced levels of Rubisco activase. Plant J 14: 101–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbinson J, Prinzenberg AE, Kruijer W, Aarts MGM (2012) High throughput screening with chlorophyll fluorescence imaging and its use in crop improvement. Curr Opin Biotechnol 23: 221–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haupt W, Scheuerlein R (1990) Chloroplast movement. Plant Cell Environ 13: 595–614 [Google Scholar]

- Hou F, Jin LQ, Zhang ZS, Gao HY (2015) Systemic signalling in photosynthetic induction of Rumex K-1 (Rumex patientia × Rumex tianschaious) leaves. Plant Cell Environ 38: 685–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard TP, Lloyd JC, Raines CA (2011) Inter-species variation in the oligomeric states of the higher plant Calvin cycle enzymes glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and phosphoribulokinase. J Exp Bot 62: 3799–3805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard TP, Metodiev M, Lloyd JC, Raines CA (2008) Thioredoxin-mediated reversible dissociation of a stromal multiprotein complex in response to changes in light availability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 4056–4061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones HG. (1999) Use of thermography for quantitative studies of spatial and temporal variation of stomatal conductance over leaf surfaces. Plant Cell Environ 22: 1043–1055 [Google Scholar]

- Jung HS, Niyogi KK (2009) Quantitative genetic analysis of thermal dissipation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 150: 977–986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser E, Kromdijk J, Harbinson J, Heuvelink E, Marcelis LFM (2017) Photosynthetic induction and its diffusional, carboxylation and electron transport processes as affected by CO2 partial pressure, temperature, air humidity and blue irradiance. Ann Bot 119: 191–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser E, Morales A, Harbinson J, Heuvelink E, Prinzenberg AE, Marcelis LFM (2016) Metabolic and diffusional limitations of photosynthesis in fluctuating irradiance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Sci Rep 6: 31252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser E, Morales A, Harbinson J, Kromdijk J, Heuvelink E, Marcelis LFM (2015) Dynamic photosynthesis in different environmental conditions. J Exp Bot 66: 2415–2426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaldenhoff R. (2012) Mechanisms underlying CO2 diffusion in leaves. Curr Opin Plant Biol 15: 276–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara M, Kagawa T, Oikawa K, Suetsugu N, Miyao M, Wada M (2002) Chloroplast avoidance movement reduces photodamage in plants. Nature 420: 829–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp AK, Smith WK (1988) Effect of water stress on stomatal and photosynthetic responses in subalpine plants to cloud patterns. Am J Bot 75: 851–858 [Google Scholar]

- Korte A, Farlow A (2013) The advantages and limitations of trait analysis with GWAS: a review. Plant Methods 9: 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer DM, Evans JR (2011) The importance of energy balance in improving photosynthetic productivity. Plant Physiol 155: 70–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger A, Weis E (1993) The role of calcium in the pH-dependent control of Photosystem II. Photosynth Res 37: 117–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kromdijk J, Głowacka K, Leonelli L, Gabilly ST, Iwai M, Niyogi KK, Long SP (2016) Improving photosynthesis and crop productivity by accelerating recovery from photoprotection. Science 354: 857–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Külheim C, Agren J, Jansson S (2002) Rapid regulation of light harvesting and plant fitness in the field. Science 297: 91–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Küppers M, Schneider H (1993) Leaf gas exchange of beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) seedlings in lightflecks: effects of fleck length and leaf temperature in leaves grown in deep and partial shade. Trees (Berl West) 7: 160–168 [Google Scholar]

- Łabuz J, Hermanowicz P, Gabryś H (2015) The impact of temperature on blue light induced chloroplast movements in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Sci 239: 238–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan Y, Woodrow IE, Mott KA (1992) Light-dependent changes in ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase activase activity in leaves. Plant Physiol 99: 304–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson T, Blatt MR (2014) Stomatal size, speed, and responsiveness impact on photosynthesis and water use efficiency. Plant Physiol 164: 1556–1570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson T, Kramer DM, Raines CA (2012) Improving yield by exploiting mechanisms underlying natural variation of photosynthesis. Curr Opin Biotechnol 23: 215–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leakey ADB, Press MC, Scholes JD (2003) Patterns of dynamic irradiance affect the photosynthetic capacity and growth of dipterocarp tree seedlings. Oecologia 135: 184–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leakey ADB, Press MC, Scholes JD, Watling JR (2002) Relative enhancement of photosynthesis and growth at elevated CO2 is greater under sunflecks than uniform irradiance in a tropical rain forest tree seedling. Plant Cell Environ 25: 1701–1714 [Google Scholar]

- Li XP, Björkman O, Shih C, Grossman AR, Rosenquist M, Jansson S, Niyogi KK (2000) A pigment-binding protein essential for regulation of photosynthetic light harvesting. Nature 403: 391–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Huang Y, Bergelson J, Nordborg M, Borevitz JO (2010) Association mapping of local climate-sensitive quantitative trait loci in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 21199–21204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XP, Müller-Moulé P, Gilmore AM, Niyogi KK (2002) PsbS-dependent enhancement of feedback de-excitation protects photosystem II from photoinhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 15222–15227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Last RL (2017) A chloroplast thylakoid lumen protein is required for proper photosynthetic acclimation of plants under fluctuating light environments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114: E8110–E8117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long SP, Zhu XG, Naidu SL, Ort DR (2006) Can improvement in photosynthesis increase crop yields? Plant Cell Environ 29: 315–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loreto F, Tsonev T, Centritto M (2009) The impact of blue light on leaf mesophyll conductance. J Exp Bot 60: 2283–2290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Barajas E, Galán-Molina J, Sánchez de Jiménez E (1997) Regulation of Rubisco activity during grain-fill in maize: possible role of Rubisco activase. J Agric Sci 128: 155–161 [Google Scholar]

- McAusland L, Davey PA, Kanwal N, Baker NR, Lawson T (2013) A novel system for spatial and temporal imaging of intrinsic plant water use efficiency. J Exp Bot 64: 4993–5007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAusland L, Vialet-Chabrand S, Davey P, Baker NR, Brendel O, Lawson T (2016) Effects of kinetics of light-induced stomatal responses on photosynthesis and water-use efficiency. New Phytol 211: 1209–1220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelet L, Zaffagnini M, Morisse S, Sparla F, Pérez-Pérez ME, Francia F, Danon A, Marchand CH, Fermani S, Trost P, et al. (2013) Redox regulation of the Calvin-Benson cycle: something old, something new. Front Plant Sci 4: 470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott KA, Woodrow IE (1993) Effects of O2 and CO2 on nonsteady-state photosynthesis. Further evidence for ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase limitation. Plant Physiol 102: 859–866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott KA, Woodrow IE (2000) Modelling the role of Rubisco activase in limiting non-steady-state photosynthesis. J Exp Bot 51: 399–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller P, Li XP, Niyogi KK (2001) Non-photochemical quenching. A response to excess light energy. Plant Physiol 125: 1558–1566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murchie EH, Harbinson J (2014) Non-photochemical fluorescence quenching across scales: from chloroplasts to plants to communities. In Demmig-Adams B, Garab G, Adams W III, Govindjee, eds, Non-photochemical Quenching and Energy Dissipation in Plants. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 553–582 [Google Scholar]

- Naranjo B, Diaz-Espejo A, Lindahl M, Cejudo FJ (2016) Type-f thioredoxins have a role in the short-term activation of carbon metabolism and their loss affects growth under short-day conditions in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Exp Bot 67: 1951–1964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumburg E, Ellsworth DS (2002) Short-term light and leaf photosynthetic dynamics affect estimates of daily understory photosynthesis in four tree species. Tree Physiol 22: 393–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikkanen L, Toivola J, Rintamäki E (2016) Crosstalk between chloroplast thioredoxin systems in regulation of photosynthesis. Plant Cell Environ 39: 1691–1705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura S, Koizumi H, Tang Y (1998) Spatial and temporal variation in photon flux density on rice (Oryza sativa L.) leaf surface. Plant Prod Sci 1: 30–36 [Google Scholar]

- Niyogi KK, Grossman AR, Björkman O (1998) Arabidopsis mutants define a central role for the xanthophyll cycle in the regulation of photosynthetic energy conversion. Plant Cell 10: 1121–1134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ort DR, Merchant SS, Alric J, Barkan A, Blankenship RE, Bock R, Croce R, Hanson MR, Hibberd JM, Long SP, et al. (2015) Redesigning photosynthesis to sustainably meet global food and bioenergy demand. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 8529–8536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterhout WJV, Haas ARC (1918) Dynamical aspects of photosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 4: 85–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto B, Uehlein N, Sdorra S, Fischer M, Ayaz M, Belastegui-Macadam X, Heckwolf M, Lachnit M, Pede N, Priem N, et al. (2010) Aquaporin tetramer composition modifies the function of tobacco aquaporins. J Biol Chem 285: 31253–31260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearcy RW. (1983) The light environment and growth of C3 and C4 tree species in the understory of a Hawaiian forest. Oecologia 58: 19–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearcy RW. (1988) Photosynthetic utilisation of lightflecks by understory plants. Aust J Plant Physiol 15: 223–238 [Google Scholar]

- Pearcy RW. (1990) Sunflecks and photosynthesis in plant canopies. Annu Rev Plant Physiol 41: 421–453 [Google Scholar]

- Pearcy RW, Krall JP, Sassenrath-Cole GF (1996) Photosynthesis in fluctuating light environments. In Baker NR, ed, Photosynthesis and the Environment. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 321–346 [Google Scholar]

- Pearcy RW, Roden JS, Gamon JA (1990) Sunfleck dynamics in relation to canopy structure in a soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) canopy. Agric For Meteorol 52: 359–372 [Google Scholar]

- Peressotti A, Marchiol L, Zerbi G (2001) Photosynthetic photon flux density and sunfleck regime within canopies of wheat, sunflower and maize in different wind conditions. Ital J Agron 4: 87–92 [Google Scholar]

- Pons TL, Pearcy RW (1992) Photosynthesis in flashing light in soybean leaves grown in different conditions. II. Lightfleck utilization efficiency. Plant Cell Environ 15: 577–584 [Google Scholar]

- Poorter H, Fiorani F, Pieruschka R, Wojciechowski T, van der Putten WH, Kleyer M, Schurr U, Postma J (2016) Pampered inside, pestered outside? Differences and similarities between plants growing in controlled conditions and in the field. New Phytol 212: 838–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price GD, von Caemmerer S, Evans JR, Yu JW, Lloyd J, Oja V, Kell P, Harrison K, Gallagher A, Badger MR (1994) Specific reduction of chloroplast carbonic anhydrase activity by antisense RNA in transgenic tobacco plants has a minor effect on photosynthetic CO2 assimilation. Planta 193: 331–340 [Google Scholar]

- Prins A, Orr DJ, Andralojc PJ, Reynolds MP, Carmo-Silva E, Parry MAJ (2016) Rubisco catalytic properties of wild and domesticated relatives provide scope for improving wheat photosynthesis. J Exp Bot 67: 1827–1838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roden JS. (2003) Modeling the light interception and carbon gain of individual fluttering aspen (Populus tremuloides Michx) leaves. Trees (Berl West) 17: 117–126 [Google Scholar]

- Roden JS, Pearcy RW (1993) Effect of leaf flutter on the light environment of poplars. Oecologia 93: 201–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruban AV. (2016) Nonphotochemical chlorophyll fluorescence quenching: mechanism and effectiveness in protecting plants from photodamage. Plant Physiol 170: 1903–1916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rungrat T, Awlia M, Brown T, Cheng R, Sirault X, Fajkus J, Trtilek M, Furbank B, Badger M, Tester M, et al. (2016) Using phenomic analysis of photosynthetic function for abiotic stress response gene discovery. Arabidopsis Book 14: e0185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford AW, Osyczka A, Rappaport F (2012) Back-reactions, short-circuits, leaks and other energy wasteful reactions in biological electron transfer: redox tuning to survive life in O(2). FEBS Lett 586: 603–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvucci ME, Portis ARJ Jr, Ogren WL (1985) A soluble chloroplast protein catalyzes ribulosebisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase activation in vivo. Photosynth Res 7: 193–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassenrath-Cole GF, Pearcy RW (1992) The role of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate regeneration in the induction requirement of photosynthetic CO2 exchange under transient light conditions. Plant Physiol 99: 227–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassenrath-Cole GF, Pearcy RW (1994) Regulation of photosynthetic induction state by the magnitude and duration of low light exposure. Plant Physiol 105: 1115–1123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassenrath-Cole GF, Pearcy RW, Steinmaus S (1994) The role of enzyme activation state in limiting carbon assimilation under variable light conditions. Photosynth Res 41: 295–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schürmann P, Buchanan BB (2008) The ferredoxin/thioredoxin system of oxygenic photosynthesis. Antioxid Redox Signal 10: 1235–1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Lai J (2015) Patterns of genomic changes with crop domestication and breeding. Curr Opin Plant Biol 24: 47–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shikanai T, Yamamoto H (2017) Contribution of cyclic and pseudo-cyclic electron transport to the formation of proton motive force in chloroplasts. Mol Plant 10: 20–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simkin AJ, McAusland L, Headland LR, Lawson T, Raines CA (2015) Multigene manipulation of photosynthetic carbon assimilation increases CO2 fixation and biomass yield in tobacco. J Exp Bot 66: 4075–4090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith WK, Berry ZC (2013) Sunflecks? Tree Physiol 33: 233–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith WK, Knapp AK, Reiners WA (1989) Penumbral effects on sunlight penetration in plant communities. Ecology 70: 1603–1609 [Google Scholar]

- Soleh MA, Tanaka Y, Nomoto Y, Iwahashi Y, Nakashima K, Fukuda Y, Long SP, Shiraiwa T (2016) Factors underlying genotypic differences in the induction of photosynthesis in soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr]. Plant Cell Environ 39: 685–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M, Grosse H (1988) Interactions between sucrose synthesis and CO2 fixation I. Secondary kinetics during photosynthetic induction are related to a delayed activation of sucrose synthesis. J Plant Physiol 133: 129–137 [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M, Lunn J, Usadel B (2010) Arabidopsis and primary photosynthetic metabolism - more than the icing on the cake. Plant J 61: 1067–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strand DD, Livingston AK, Satoh-Cruz M, Froehlich JE, Maurino VG, Kramer DM (2015) Activation of cyclic electron flow by hydrogen peroxide in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 5539–5544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinnen G, Goossens A, Pauwels L (2016) Lessons from domestication: targeting cis-regulatory elements for crop improvement. Trends Plant Sci 21: 506–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadrist L, Saudreau M, de Langre E (2014) Wind and gravity mechanical effects on leaf inclination angles. J Theor Biol 341: 9–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, Izumi W, Tsuchiya T, Iwaki H (1988) Fluctuation of photosynthetic photon flux density within a Miscanthus sinensis canopy. Ecol Res 3: 253–266 [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SH, Long SP (2017) Slow induction of photosynthesis on shade to sun transitions in wheat may cost at least 21% of productivity. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 372: 1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tcherkez G. (2013) Modelling the reaction mechanism of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase and consequences for kinetic parameters. Plant Cell Environ 36: 1586–1596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tholen D, Boom C, Noguchi K, Ueda S, Katase T, Terashima I (2008) The chloroplast avoidance response decreases internal conductance to CO2 diffusion in Arabidopsis thaliana leaves. Plant Cell Environ 31: 1688–1700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tholen D, Ethier G, Genty B, Pepin S, Zhu X-G (2012) Variable mesophyll conductance revisited: theoretical background and experimental implications. Plant Cell Environ 35: 2087–2103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thormählen I, Zupok A, Rescher J, Leger J, Weissenberger S, Groysman J, Orwat A, Chatel-Innocenti G, Issakidis-Bourguet E, Armbruster U, et al. (2017) Thioredoxins play a crucial role in dynamic acclimation of photosynthesis in fluctuating light. Mol Plant 10: 168–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinoco-Ojanguren C, Pearcy RW (1993) Stomatal dynamics and its importance to carbon gain in two rainforest Piper species: II. Stomatal versus biochemical limitations during photosynthetic induction. Oecologia 94: 395–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehlein N, Otto B, Hanson DT, Fischer M, McDowell N, Kaldenhoff R (2008) Function of Nicotiana tabacum aquaporins as chloroplast gas pores challenges the concept of membrane CO2 permeability. Plant Cell 20: 648–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rooijen R, Kruijer W, Boesten R, van Eeuwijk FA, Harbinson J, Aarts MGM (2017) Natural variation of YELLOW SEEDLING1 affects photosynthetic acclimation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Comm 8: 1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vialet-Chabrand S, Matthews JSA, Simkin AJ, Raines CA, Lawson T (2017a) Importance of fluctuations in light on plant photosynthetic acclimation. Plant Physiol 173: 2163–2179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vialet-Chabrand SRM, Matthews JSA, McAusland L, Blatt MR, Griffiths H, Lawson T (2017b) Temporal dynamics of stomatal behavior: modeling and implications for photosynthesis and water use. Plant Physiol 174: 603–613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vico G, Manzoni S, Palmroth S, Katul G (2011) Effects of stomatal delays on the economics of leaf gas exchange under intermittent light regimes. New Phytol 192: 640–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachendorf M, Küppers M (2017) The effect of initial stomatal opening on the dynamics of biochemical and overall photosynthetic induction. Trees (Berl West) 31: 981–995 [Google Scholar]

- Way DA, Pearcy RW (2012) Sunflecks in trees and forests: from photosynthetic physiology to global change biology. Tree Physiol 32: 1066–1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams WE, Gorton HL, Witiak SM (2003) Chloroplast movements in the field. Plant Cell Environ 26: 2005–2014 [Google Scholar]

- Woodrow IE, Kelly ME, Mott KA (1996) Limitation of the rate of ribulosebisphosphate carboxylase activation by carbamylation and ribulosebisphosphate carboxylase activase activity: development and tests of a mechanistic model. Aust J Plant Physiol 23: 141–149 [Google Scholar]

- Woodrow IE, Mott KA (1989) Rate limitation of non-steady-state photosynthesis by ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase in spinach. Aust J Plant Physiol 16: 487–500 [Google Scholar]

- Yamori W, Masumoto C, Fukayama H, Makino A (2012) Rubisco activase is a key regulator of non-steady-state photosynthesis at any leaf temperature and, to a lesser extent, of steady-state photosynthesis at high temperature. Plant J 71: 871–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X, Struik PC (2017) Simple generalisation of a mesophyll resistance model for various intracellular arrangements of chloroplasts and mitochondria in C3 leaves. Photosynth Res 132: 211–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Kallis RP, Ewy RG, Portis AR Jr (2002) Light modulation of Rubisco in Arabidopsis requires a capacity for redox regulation of the larger Rubisco activase isoform. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 3330–3334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Portis AR Jr (1999) Mechanism of light regulation of Rubisco: a specific role for the larger Rubisco activase isoform involving reductive activation by thioredoxin-f. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 9438–9443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu XG, Ort DR, Whitmarsh J, Long SP (2004) The slow reversibility of photosystem II thermal energy dissipation on transfer from high to low light may cause large losses in carbon gain by crop canopies: a theoretical analysis. J Exp Bot 55: 1167–1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]