Abstract

Even though guidelines strongly recommend that patients receive a statin for secondary prevention after an acute myocardial infarction (MI), many elderly patients do not fill a statin prescription within 30 days of discharge. This paper assesses whether patterns of statin use by Medicare beneficiaries post-discharge may be due to a mix of high-quality and low-quality physicians. Our data come from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Chronic Condition Data Warehouse (CCW) and include 100% of Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for an acute myocardial infarction in 2008 or 2009. Our study sample included physicians treating at least 10 Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries during their MI institutional stay. Physician-specific statin fill rates (the proportion of each physician’s patients with a statin within 30 days post-discharge) were calculated to assess physician quality. We hypothesized that if the observed statin rates reflected a mix of high-quality and low-quality physicians, then physician-specific statin fill rates should follow a u-shaped or bimodal distribution. In our sample, 62% of patients filled a statin prescription within 30 days of discharge. We found that the distribution of statin fill rates across physicians was normal, with no clear distinctions in physician quality. Physicians, especially cardiologists, with relatively younger and healthier patient populations had higher rates of statin use. Our results suggest that physicians were engaging in patient-centered care, tailoring treatments to patient characteristics.

Keywords: statins, prevention, cardiovascular disease, acute myocardial infarction, Medicare, physician quality

There is growing concern in the medical community regarding quality measures and guidelines that do not account for the art of prescribing and the complexity of the patient.1,2 Pressure exists from payers and regulating agencies for physicians to conform to guidelines, and some have argued that one way to reduce costs is to require adherence to clinical guidelines.3 However, restricting flexibility in the treatment decision may in the end jeopardize patient-centered care.4 Cooper and Strauss discuss their concern for the potential tyranny of guidelines in a recent paper, stating that “guidelines are expressions of the optimal pathway for the average patient, but, of course, most patients are not average (pp.233).”5 Finding the correct balance between following guidelines and patient-centered care is relatively uncharted territory and open to scientific inquiry.

We were struck with this very tension in our own study of treatments prescribed to a population of elderly patients who experienced an acute myocardial infarction (MI). Current guidelines recommend that patients with an acute MI receive a statin for secondary prevention.6,7 The evidence for statin use is so strong that some have labeled it “effective care,” such that all patients should be receiving it unless significant contraindications exist, such as hypersensitivity, unexplained persistent elevations of serum transaminases, or pregnant or nursing mothers.8,9 As these conditions affect a small percentage of the population, treatment rates substantially less than 100% could be thought by some as underuse or ineffective care delivery. Indeed, prescribing a statin post-acute MI is now a Joint Commission core measure and a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) inpatient quality reporting measure.

However, studies have reported statin rates far less than 100%. According to the Dartmouth Atlas 2013 Medicare prescription drug use, 76.9% of survivors filled a statin prescription within 6 months of post-MI discharge.9 We found that only 62% of our study cohort (Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized in 2008-2009 for an acute MI) had a statin available within 30 days of discharge, either through a new statin prescription or through pills remaining from a prescription prior to their MI.10 This discordance between guidelines and practice prompted us to question whether these observed statin rates suggested that only 62% of physicians were providing high-quality care, or, whether physicians, who in general were providing quality care, believed that some patients might not sufficiently benefit from a statin post-discharge.

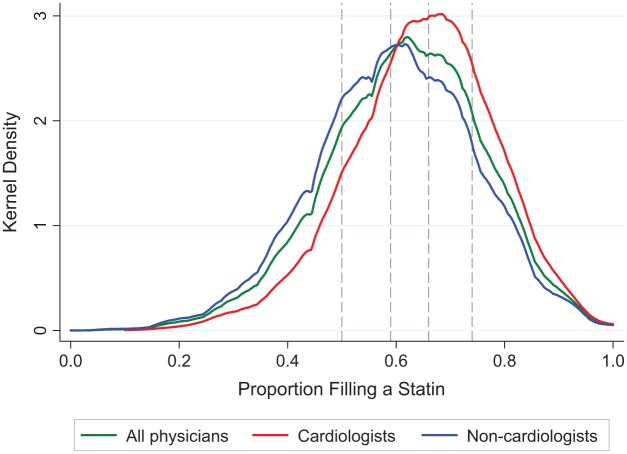

To test this, we plotted the distribution of statin fill rates for the physicians in our sample. If it is the case that only 62% of physicians were prescribing statins (thus providing high-quality care) and 38% of physicians were providing low-quality care by not prescribing statins, then we would expect the distribution of fill rates across physicians to consist of 2 spikes, one at 0% and another at 100% (ie, 62% of physicians prescribe statins to 100% their patients and 38% of physicians prescribe statins to none of their patients). A more moderate version of this story (that the observed statin rates are due to a mix of high-quality and low-quality physicians) could be evidenced by a bimodal distribution of physician-specific statin fill rates, with means near 0% and 100%. If it was the case instead that 62% of every physician’s patients received a statin, then the distribution of fill rates across physicians would be observed as a single spike at 62%. Another potential scenario would be one where the physician-specific fill rates were normally distributed with a mean of 62%, implying that most of the patients for each physician received a statin, with some physicians having a higher or lower fill rate. A normal distribution could further imply that patient-centered care was being provided if the patients of doctors with lower fill rates were clinically different from patients of doctors with higher fill rates. In other words, it could be that some doctors had lower fill rates because their patient population was sicker and older than those with higher fill rates. This could be tested empirically by comparing patient characteristics across quintiles of the statin fill rate distribution.

Methods

The Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse (CCW) provided Medicare claims files, enrollment information and Part D events for all patients hospitalized with an acute MI in 2008 or 2009. For this analysis, we started with a previously constructed patient population.10 This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board.

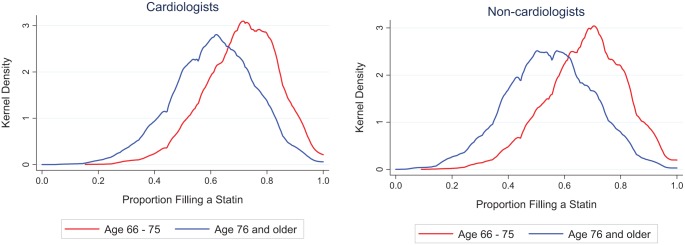

From Medicare claims, we identified every unique physician (from their National Provider Identifier) that our patient sample encountered while institutionalized. Each of the patients was assigned to every physician with whom they had a visit during their institutional stay, so that a single patient may be associated with multiple physicians. We then determined the proportion of patients for each physician that had a statin available in the 30-days post-discharge (either through a new prescription or an existing one with remaining pills) and designated this as the statin “fill rate” for each physician. Only physicians who saw at least 10 patients over our 2-year study period were included in the analysis, so that fill rates could be calculated with sensitivity. We calculated and designated fill rates for (1) all physicians and (2) cardiologists and non-cardiologists (identified by specialty codes reported on the claims). In addition to the full patient population, we also calculated fill rates for “younger” patients (66-75 years old) and “older” patients (aged 76 and older) by physician specialty (cardiologists and non-cardiologists). This age cutoff was chosen to mirror current guidelines.6

Kernel density plots were drawn to visualize the distribution of statin fill rates across physicians. A bandwidth of 0.025 was chosen for the half-width of the kernel. Physicians (and their associated patients) were then grouped into quintiles based on their statin fill rate. These quintiles were created for the full sample (all physicians and all patients). Patient characteristics, such as age, gender, severity of acute MI (measured as an anterior wall MI or non-ST-segment elevation MI (non-STEMI)), comorbidity (documented chronic kidney disease, diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, or stroke in the year prior to acute MI) were compared across the quintiles using a Cochran–Armitage trend test. All analyses were done using Stata Version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas).

Results

Our sample included 38,822 physicians (20,574 cardiologists and 18,248 non-cardiologists) and 123,432 patients (50,431 patients 66-75 years old and 73,001 patients aged 76 and older). The ranges of statin fill rates (and median) for physicians grouped by quintile were 0% to 50% (42%) in the first/lowest quintile, 50% to 59% (55%) in the second quintile, 60% to 66% (63%) in the third quintile, 67% to 74% (70%) in the fourth quintile, and 75% to 100% (79%) in the highest/fifth quintile (see Table 1). Even for physicians in the highest quintile (ie, most likely to have had patients receive a statin within 30 days of discharge) half had statin fill rates much nearer the lower bound of that quintile (ie, within 5 percentage points of the minimum, which was 75%) than the maximum for that quintile (100%). The distribution of physician-specific statin fill rates was normal, with very few physicians in either tails (see Figure 1). Cardiologists were on average more likely to have had patients fill statins (65%) than non-cardiologists (60%). Stratifying by patient age, statin fill rates were again normally distributed (regardless of physician specialty) although the means of the distributions were not equal (see Figure 2). Older patients were less likely to have a statin than younger patients. For cardiologists, 71% of patients aged 66 to 75 and 66% of patients 76 and older had a statin available within 30 days of discharge. The means for non-cardiologists were lower: 68% (aged 66-75) and 55% (aged 76 and older). Regardless of specialty, there seemed to be more agreement in how to treat the younger patients, as the standard deviation for these distributions was smaller. Even so, the shape of all our statin fill rate distributions remained normal (rather than spiked or bimodal).

Table 1.

Proportion of Patients in Each Physician-Specific, Statin Fill Rate Quintile, by Patient Characteristics.

| Quintile |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowest |

Highest |

Cochran–Armitage trend test | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Median statin fill rate | 42% | 55% | 63% | 70% | 79% | |

| Chronic kidney disease in the year prior to admission | 22% | 20% | 18% | 17% | 16% | P < .0001 |

| Non-serious myopathy in the year prior to admission | 16% | 16% | 15% | 14% | 13% | P < .0001 |

| Diabetes in the year prior to admission | 42% | 40% | 39% | 38% | 37% | P < .0001 |

| Hypertension in the year prior to admission | 84% | 83% | 82% | 81% | 79% | P < .0001 |

| Heart failure in the year prior to admission | 35% | 30% | 28% | 26% | 23% | P < .0001 |

| Stroke in the year prior to admission | 6% | 5% | 5% | 4% | 4% | P < .0001 |

| Anterior wall MI diagnosed at admission | 5% | 7% | 8% | 8% | 9% | P < .0001 |

| Non-STEMI diagnosed at admission | 80% | 76% | 74% | 73% | 71% | P < .0001 |

| Male | 42% | 44% | 46% | 47% | 49% | P < .0001 |

| Age 66 to 70 at admission | 20% | 22% | 24% | 24% | 26% | P < .0001 |

| Age 71 to 75 at admission | 21% | 22% | 23% | 23% | 24% | P < .0001 |

| Age 76 to 80 at admission | 20% | 21% | 22% | 22% | 22% | P < .0001 |

| Age 81 to 85 at admission | 20% | 19% | 18% | 18% | 17% | P < .0001 |

| Age 85 and older at admission | 20% | 16% | 14% | 13% | 11% | P < .0001 |

Note. MI=myocardial infarction, Non-STEMI = non-ST-segment elevated MI.

Figure 1.

Kernel density plot of physician-specific, statin fill rates, by physician specialty, and quintile cutoffs for the full sample of physicians.

Figure 2.

Kernel density plot of physician-specific, statin fill rates for cardiologists and non-cardiologists, by patient age.

Patient characteristics for each statin fill rate quintile are reported in Table 1, along with results of the Cochran–Armitage trend tests. Our results suggest that patients of physicians with low statin fill rates were significantly different than patients of physicians with high fill rates. For example, for the physicians in the lowest statin fill rate quintile, 22% of their patients had chronic kidney disease documented in the year prior to their acute MI, compared with 16% of patients for the physicians in the highest quintile. The patients of physicians in the higher fill rate quintiles were younger, had fewer comorbidity, and more serious MI (all Ps < .0001).

Conclusions

Although guidelines strongly recommend statin use in patients after an acute MI,6 only 62% of patients in our cohort (65% of cardiologists’ patients) received one within 30 days of institutional discharge. Our data suggested that this is not due to a mix of high-quality and low-quality physicians, which would have been evidenced by a u-shaped or bimodal distribution in physician-specific statin fill rates. Instead, the normally distributed fill rates (along with the differences in patient characteristics across quintiles) suggest that physicians were engaging in patient-centered care, sorting their patients into treatments and prescribing statins to those they thought would experience the most cardiovascular disease risk reduction benefit with the fewest adverse effects.

There are limitations to our study. First, we included only physicians with at least 10 patients. Thus, our results are not generalizable to all physicians who treated acute MI patients in 2008-2009. However, we felt that this was a necessary inclusion criterion to ensure that our calculated statin fill rates were sufficiently sensitive. The mean and median statin fill rate for this smaller sample of physicians was no different than the rate of statin use for the full sample.

Also, our measure of medication use required that the patients covered by Medicare Part D used their benefits. The availability of $4 generic statins may have resulted in some individuals paying for their medications with cash, bypassing Part D altogether, and being inappropriately labeled in our analyses as an individual with no statin. This will only affect the distribution of the physician-specific statin fill rates if these patients are not randomly distributed across physicians. It could be argued that certain physicians may be located in areas where the majority of their patients are lower income. However, the poorest patients (who may also tend to have more comorbidity) would qualify for the low-income subsidy, and their medications under Part D would cost less than $4 so that they would have no incentive to pay $4 in cash for their statin. Thus, only the individuals with out-of-pocket costs greater than $4 would be incentivized to pay cash for their statin. Paying cash, though, would not accrue their total drug costs under Part D and could adversely affect their future benefit phases. In addition, we do observe $4 statins in our Part D events; 5% of our study patients paid exactly $4 and an additional 5% paid less than $4. Although we do not know how many patients paid cash for their statins, we do observe a number of patients paying $4, suggesting that when given the option to pay cash, some individuals are still choosing to obtain their medications through Medicare.

Finally, we are aware that estimating physician-specific statin utilization rates using “filled claims” may not reflect prescribing intent. It is possible that the normal distribution we observe across physicians reflects the distribution in patient adherence to statins across the patients treated by each physician. It could be the case that 100% of physicians are prescribing statins to 100% of their patients, but that 38% of the patients are choosing to not fill a prescribed statin in such a way to make the distribution of physician-specific fill rates appear normal.

Previous work has shown that patient characteristics do affect the propensity to fill a prescription (ie, primary adherence), both in a population-based outpatient sample11 and for those who experienced an acute MI.12 For example, Jackevicius et al. found that patients with diabetes were more than 1.26 times more likely to fill their prescriptions post-MI. In our sample, physicians in the first quintile had the greatest proportion of diabetic patients, and thus the observed fill rate in this quintile may be higher than if the proportion of diabetic patients across physicians was uniform. However, Jackevicius et al. also report that patients with heart failure are 0.45 times as likely to fill their prescriptions post-discharge as those without heart failure. The first quintile (which had the highest proportion of diabetics per physician) also had the highest proportion of heart failure patients. Thus, any bias in fill rates from the diabetics (who were more likely to fill the prescriptions) would be counterbalanced by the greater proportion of heart failure patients (who were much less likely to fill the prescriptions). All of our patient characteristics were distributed across the quintiles linearly (significantly increasing or decreasing across the quintiles) and a number of them were reported in the papers by Jackevicius et al. and Fischer et al. as factors influencing primary adherence. This would imply that the impact of primary adherence would be greatest at the tails, and not toward the major bulk in the distribution of physician-specific fill rates. In addition, it has been reported that more than 90% of MI patients fill their statin prescriptions within 30 days of discharge.12 Thus, even with patient factors driving primary adherence, the effect would be most pronounced in the tails and limited by the fact that only 10% of MI patients fail to fill their statin prescription within 30 days of discharge. In conclusion, the true distribution of physician-specific statin-prescribing rates is likely similar to ours, and suggests that, at least in this sample, there is no clear distinction in physician quality, and that physicians play a substantial role in tailoring prescribing decisions to the individual characteristics of their patients. This conclusion is corroborated by a recent Canadian study that found that statin rates post-acute MI correlated strongly with expected life expectancy.13

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Dr. Schroeder has received research grants to her institution from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Dr. Chapman has received research grants to his institution from NIH, AHRQ, and PCORI. Dr. Robinson has received research grants to her institution from the following entities: NIH, AHRQ, PCORI, Amarin, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo, Esperion, Genentech/Hoffman-La Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Regeneron/Sanofi, Zinfandel/Takeda. She has also served as a consultant for Amgen, Pfizer, Sanofi, Regeneron, and Merck. Dr. Brooks has received funding from PCORI, NIH, and AHRQ. None of these entities funded any part of this current work (other than that stated in the Funding section).

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grant (1R21HS019574-01) under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.

References

- 1. Kamerow D. How can we treat multiple chronic conditions? BMJ. 2012;344:e1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tinetti ME, Bogardus ST, Jr., Agostini JV. Potential pitfalls of disease-specific guidelines for patients with multiple conditions. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(27):2870-2874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kocher R, Sahni NR. Hospitals’ race to employ physicians—the logic behind a money-losing proposition. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(19):1790-1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Solomon J, Raynor DK, Knapp P, Atkin K. The compatibility of prescribing guidelines and the doctor-patient partnership: a primary care mixed-methods study. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62(597):e275-e281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cooper RA, Straus DJ. Clinical guidelines, the politics of value, and the practice of medicine: physicians at the crossroads. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8(4):233-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25, pt B):2889-2934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smith SC, Jr., Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ACCF Secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2011;124(22):2458-2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wallace E, Smith SM, Fahey T. Variation in medical practice: getting the balance right. Fam Pract. 2012;29(5):501-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Munson JC, Morden NE, Goodman DC, Valle LF, Wennberg JE. The Dartmouth Atlas of Medicare Prescription Drug Use. 2013. Lebanon, NH: Dartmouth Institute For Health Policy & Clinical Practice. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brooks JM, Cook EA, Chapman CG, et al. Geographic variation in statin use for complex acute myocardial infarction patients: evidence of effective care? Med Care. 2014;52(suppl 3):S37-S44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fischer MA, Stedman MR, Lii J, et al. Primary medication non-adherence: analysis of 195,930 electronic prescriptions. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(4):284-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jackevicius CA, Li P, Tu JV. Prevalence, predictors, and outcomes of primary nonadherence after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;117:1028-1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ko DT, Austin PC, Tu JV, Lee DS, Yun L, Alter DA. Relationship between care gaps and projected life expectancy after acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7(4):581-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]