Abstract

Section 3025 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 established the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP), an initiative designed to penalize hospitals with excess 30-day readmissions. This study investigates whether readmission penalties under HRRP impose significant reputational effects on hospitals. Data extracted from 2012 to 2013 news stories suggest that the higher the actual penalty, the higher the perceived cost of the penalty, the more likely it is that hospitals will state they have no control over the low-income patients they serve or that they will describe themselves as safety net providers. The downside of being singled out as a low-quality hospital deserving a relatively high penalty seems to be larger than the upside of being singled out as a high-quality hospital facing a relatively low penalty. Although the financial burden of the penalties seems to be low, hospitals may be reacting to the fact that information about excess readmissions and readmission penalties is being released widely and is scrutinized by the news media and the general public.

Keywords: hospital readmissions, penalty, Medicare, quality, news media

Introduction

Nearly one out of every five Medicare patients discharged from a hospital returns to a hospital within a month.1 The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) estimates that reducing the 30-day hospital readmission rate for Medicare patients may generate substantial savings given that three out of every four readmissions are considered to be preventable.1 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) estimates that the costs of readmissions are as high as US$17 billion each year.2

Effective October 1, 2012, Section 3025 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 established the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP), an initiative designed to penalize hospitals with excess 30-day readmissions.1 In the first year of the program, Medicare payments to hospitals were subject up to a 1% penalty if a hospital had risk-adjusted excess 30-day readmissions for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure, and pneumonia during the previous 3 years. During the first year of the program, roughly 70% of hospitals received a penalty (2217 hospitals) with an average 0.28% reduction in Medicare payments overall.3 Penalties of less than 1% were assessed to 1910 hospitals, and penalties of one hundredth of a percent were assessed to 49 hospitals. About two million Medicare beneficiaries are readmitted every year within 30 days of hospital discharge.3

Although the size of the HRRP penalty has been relatively small for most hospitals, 30-day readmission rates and the associated penalty for each hospital has been widely disseminated in the news media. Optimal penalty theory suggests that the expected total penalty (ie, economic and reputational penalties) should equal the social cost of the activity or behavior being penalized.4 The low dollar value of the HRRP penalty for most hospitals suggests that for the program to be effective, the reputational penalty would have to be much larger than the economic penalty.

A hospital may react to the reputational effects of the program differently depending on whether or not it was penalized. For example, many hospitals have publicly criticized the program for being “unfair” because, they argue, it disproportionately affects safety net hospitals and it fails to recognize that external factors outside the control of the hospital drive readmission rates.5,6 John Lynch, the medical director at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri called the penalties “the price that many hospitals will pay for taking care of underserved populations.”5,6 Other hospitals have blamed high readmission rates on internal factors, such as having inadequate nursing staff levels and being related to the past behavior of physician groups.7,8

Some hospitals have taken a more proactive stance by stating that reducing readmissions was a top priority at their institution and that they had already developed new programs to reduce readmission rates through improvement in transitional care, including implementing telehealth services and hiring case managers to keep track of patients after a hospital discharge.9,10 Greg Baxter, chief medical officer at Elliot Hospital in Manchester, New Hampshire stated, “The dollar impact is less impressive than the call to action to meet or exceed an increasing level of performance.”11

The purpose of this study is to investigate whether readmission penalties under HRRP impose significant reputational effects on hospitals and whether these effects vary based on the size of the penalty. We do this by analyzing news media coverage of the readmission penalties assessed to hospitals across the United States and how hospitals responded when they were singled out in specific news stories about the penalties.

Study Data and Methods

To analyze the effects of hospital readmission penalties on the reputation and response of hospitals, we used the LexisNexis Academic database to identify news stories between August 2012 and July 2013 that addressed hospital readmission penalties. The search terms used included “hospital,” “readmission,” and “penalty.” We identified 305 news stories that met these criteria. Each investigator (the three authors of this article) then read the news stories and identified whether a specific hospital was mentioned either in the main narrative or a table accompanying the news story. Themes within different categories of relevance were identified by randomly selecting 10% of the articles and then developing a list of themes within each category that was used for consistent coding. The category selection process involved using preselected themes based on our knowledge of HRRP and its potential effects obtained from news stories, the academic literature and technical reports, as well as by the reading of 10% of the articles identified to reassess and refine preselected themes.

The categories used in the final coding (themes are listed in parentheses) included how the size of the readmission penalty was related to the perceived size of the penalty (the hospital is mentioned in the story as having received a high/large or low/small readmission penalty), external factors driving the penalty (the hospital describes its readmission penalty as unfair or beyond the hospital’s control; the hospital considers the penalty to be costly; the hospital has no control over low-income patients; and hospital describes itself as being a safety net provider), and the degree to which a hospital is being proactive about the problem (the hospital is trying to improve transitional care; reducing readmissions is a top priority; the hospital has already reduced readmissions substantially and, as a result, the future penalty will be lower; and the hospital decided not to issue any comments about the penalty assessed in the news story where it was mentioned). Once a list of hospitals referenced in the articles was developed, yes/no responses on whether a theme was part of a given story mentioning a hospital were recorded by each independent coder. The final selection of responses to a given theme was based on whether at least two of the three coders selected the theme for a particular hospital.

Other themes considered included whether the hospital described the readmission penalty as being related to past behavior from a physician group, being a teaching hospital, having inadequate nursing staff levels, lacking community resources, and having a large number of patients with behavioral health problems. We also considered whether the hospital perceived to have control over uninsured patients and whether the hospital had a low mortality rate. Less than 1% of the news stories analyzed mentioned that hospitals were facing any of these issues.

We analyzed data on 304 instances in 83 news stories in which a theme was mentioned for a given hospital. We used these data to estimate logistic regression models and evaluate the relation between the actual readmission penalty assessed to a given hospital and the themes that are related to the size of the penalty and the reaction of the hospital to the penalty. A 1% penalty is is likely to be more significant (and detrimental) to a hospital located in a market where other hospitals faced lower penalties than in a market where everyone else paid the same 1% maximum penalty. As such, although the actual financial penalty can be mapped to an absolute dollar amount, the reputational penalty and hospital reactions are relative concepts that depend on how every other hospital in the local market fared.

Data for readmission penalties were obtained by subtracting the payment factor for each hospital (provided by CMS) by 1 and then multiplying this figure by 100. The logistic regression models were adjusted by hospital ownership structure (for-profit status, non-profit/government), number of staffed beds per 100 patients, and number of hospital discharges per 1000 patients. State random effects were also included in all logistic regression models.

Study Findings

The specific definition of the themes analyzed and the descriptive statistics for the study sample are reported in Table 1. Almost 41% of the hospitals mentioned in the news stories evaluated were thought to have received a perceived high or large readmission penalty whereas 29.61% of the hospitals were thought to have received a perceived low or small readmission penalty. About 2.30% of hospitals described the readmission penalty as unfair or beyond the hospital’s control, 2.96% described it as costly, 2.30% mentioned that the hospital had no control over low-income patients, and 1.64% described itself as being a safety net provider of hospital services. Almost 35% of hospitals stated that they were trying to improve transitional care, 5.59% stated that reducing readmissions was a top priority, and 10.53% mentioned that they had already reduced readmissions substantially and, thus, expected future penalties to be lower. Only 3.29% of hospitals mentioned in news stories had representatives stating that they did not want to comment on the story.

Table 1.

Definition of Themes and Descriptive Statistics for the Study Sample—News Stories on Hospital Readmission Penalties from September 2012 to August 2013.

| Categories/themes | % |

|---|---|

| Perception of size of readmission penalty | |

| Hospital mentioned to have received a high/large readmission penalty | 40.79 |

| Hospital mentioned to have received low/small readmission penalty | 29.61 |

| External factors drive penalty | |

| Hospital describes readmission penalty as unfair or beyond the hospital’s control | 2.30 |

| Hospital describes readmission penalty as costly | 2.96 |

| Hospitals has no control over low-income patients | 2.30 |

| Hospital describes itself as being a safety net hospital | 1.64 |

| Hospital is being proactive | |

| Hospital is trying to improve transitional care | 34.54 |

| Reducing readmissions is a top priority | 5.59 |

| Hospital has already reduced readmissions substantially and future penalty expected to be lower | 10.53 |

| Hospital has no comment | |

| Hospital representatives did not want to comment on the story | 3.29 |

Source. Authors’ own estimates from an analysis of news stories on hospital readmission penalties from September 2012 to August 2013.

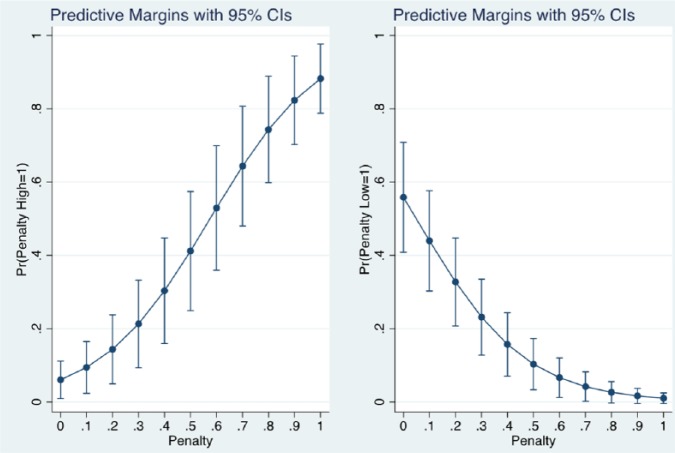

Table 2 reports the results of logistic regression models of how the size of the penalty is related to the hospital-specific themes coded in the news stories. The penalty variable ranges from a 0 to a 1% fine and, as such, we scaled it by 10 to ease interpretation (ie, a unit change represents a 10 percentage point shift in the penalty). The actual magnitude of the penalty was related positively to a hospital being perceived as receiving a high or large penalty (odds ratio [OR] = 1.62, 95% confidence interval [CI] = [1.42, 1.84]) and negatively related to a hospital being perceived as receiving a low or small penalty (OR = 0.61, 95% CI = [0.53, 0.72]). Moreover, high perceived penalties were more variable with the actual 0 to 1 penalty range than low perceived penalties. The predicted probability of a high perceived penalty under the minimum penalty received (no actual penalty) was .06 compared with a predicted probability of a high perceived penalty under the maximum penalty received (full penalty) of .88. However, the predicted probability of a low perceived penalty under the minimum penalty received (no actual penalty) was .56 compared with a predicted probability of a low perceived penalty under the maximum penalty received (full penalty) of .01. This result is shown in Figure 1 for the full range of predicted probabilities for high and low penalties.

Table 2.

Hospital Readmission Penalties and Categories/Themes in News Stories.

| Predicted probability for penalty of size |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categories/themes | Odds ratio (95% CI) | .00 | .25 | 1.00 |

| Perception of size of readmission penalty | ||||

| Hospital mentioned to have received a high/large readmission penalty | 1.62 [1.42, 1.84] | .06 | .20 | .88 |

| Hospital mentioned to have received low/small readmission penalty | 0.61 [0.53, 0.72] | .56 | .25 | .01 |

| External factors drive penalty | ||||

| Hospital describes readmission penalty as unfair or beyond the hospital’s control | 1.28 [0.99, 1.66] | .01 | .01 | .06 |

| Hospital describes readmission penalty as costly | 1.27 [1.00, 1.62] | .00 | .01 | .04 |

| Hospitals has no control over low-income patients | 1.57 [1.09, 2.25] | .00 | .01 | .11 |

| Hospital describes itself as being a safety net hospital | 1.40 [1.01, 1.95] | .00 | .01 | .08 |

| Hospital is being proactive | ||||

| Hospital is trying to improve transitional care | 0.96 [0.89, 1.04] | .39 | .36 | .30 |

| Reducing readmissions is a top priority | 1.04 [0.86, 1.25] | .02 | .02 | .03 |

| Hospital has already reduced readmissions substantially and future penalty expected to be lower | 1.10 [1.00, 1.22] | .07 | .09 | .17 |

| Hospital has no comment | ||||

| Hospital representatives did not want to comment on the story | 0.99 [0.77, 1.27] | .01 | .01 | .01 |

Source. Authors’ own estimates from an analysis of news stories on hospital readmission penalties from September 2012 to August 2013.

Note. Hospital readmission penalties are rescaled by 10 in the random effects logistic regression analysis. Odds ratios are adjusted for the number of hospital beds, total number of hospital discharges, and hospital ownership (for-profit vs. other). CI = confidence interval.

Figure 1.

Hospital mentioned to have received a high/low penalty by magnitude of the penalty.

Source. Authors’ own estimates based on analysis of news stories.

Note. CI = confidence interval.

The actual penalty assessed to hospitals seems to be related to external factors, that is, the higher the actual penalty, the more likely that a hospital would describe the readmission penalty as costly (OR = 1.27, 95% CI = [1.00, 1.62]), that the hospital has no control over low-income patients (OR = 1.57, 95% CI = [1.09, 2.25]), and that the hospital would describe itself as a safety net provider (OR = 1.40, 95% CI = [1.01, 1.95]).

We also estimated the logistic regression models with a binary penalty variable (defined as being assessed a penalty vs. no penalty, and being assessed a penalty at or above the average of 0.28 or below the average; logistic regression results not shown). Hospitals assessed a penalty above the average penalty imposed to all hospitals were more likely to state that they were already reducing readmissions substantially and, thus, future penalties were expected to be lower (OR = 2.55, 95% CI = [1.14, 5.71]). Last, although the logistic regression coefficients for most of the other factors evaluated in the study had the expected sign, they were not statistically significant at P < .05.

Discussion

Although the size of the HRRP penalty was relatively small for most hospitals during the first year of operation of the new program, 30-day readmission rates and the associated penalty assessed to each hospital have been widely disseminated in the news media. This type of media exposure at the local, state, and national levels for a given hospital may impose significant reputational effects that go beyond the size of the readmission penalty assessed.

Our analysis of news stories from the first year of operation of HRRP suggests that the higher the actual penalty, the higher the perceived cost of the penalty, the more likely it is that the hospital would state it has no control over the low-income patients it serves, and the more likely it is that a hospital will describe itself as a safety net provider of hospital services. Moreover, hospitals that were assessed an above-average penalty were more likely to state that they were already reducing readmissions substantially and, as a result of these efforts, they expected the future penalty to be lower.

Our results also showed some evidence of asymmetries in the impact of the actual penalty. Actual penalties were more strongly related to high perceived penalties than to low perceived penalties in the sense that the marginal impact of the actual penalty was higher, in absolute terms, for larger compared to smaller perceived penalties. What this may mean is that hospitals react more strongly to news emphasizing a high or large penalty compared with stories emphasizing a low or small penalty. In other words, the downside of being singled out as a low-quality hospital deserving a relatively high penalty is larger than the upside of being singled out as a high-quality hospital facing a relatively low penalty.

Conclusion

Optimal penalty theory suggests that the expected total penalty of HRRP should take into account both the economic and reputational effects of the penalty on hospitals. An efficient penalty would be one where the expected total penalty equals the social cost of the activity or behavior being punished. The results from this study suggest that although at first the monetary value of hospital readmission penalties seems to be relatively low, hospitals are reacting to the fact that information about excess readmissions and readmission penalties is being released widely and is scrutinized by the news media and the general public. High penalties elicit a stronger reaction than low penalties and some hospitals that were assessed high penalties have argued that the reason for these high penalties is due to factors beyond their control (ie, that they serve low-income patients or are safety net providers).

Readmission penalties were designed to incentivize hospitals to improve the quality of care that may be reflected in excess hospital readmissions for selected health conditions. If the financial and reputational penalties are set too high or too low, then this may lead to suboptimal behavior on the part of hospitals (eg, hospitals may allocate too many resources to avoid being penalized given the high costs of penalties or, in the other extreme, they may ignore the penalties altogether). The fact that hospitals tend to react more to negative than positive results suggests that the penalties are having an effect and this effect is larger than what would be expected if there was only a financial component to the penalty program.

The size of the readmission penalties under HRRP continues to increase (from 2% in Fiscal Year 2014 to 3% in Fiscal Year 2015 and beyond) and the number of health conditions being tracked to assess the penalty is also expected to increase from pneumonia, AMI, and stroke, to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), elective total hip arthroplasty (THA), and total knee arthroplasty (TKA). What this means is that the expected total penalty will continue to increase for hospitals due to both financial and reputational factors. To fully assess the effects of the readmission penalties, there is a need to collect more news media data for the second and third years of HRRP. Our findings are likely to be stronger if data were analyzed for subsequent years of the program.

Last, it is unclear whether this hospital readmission penalty structure is efficient, that is, if the full (financial and reputational) penalty is equal to the social cost of the activity being penalized. This is a difficult but important question to answer in the sense that a lower than optimal full readmission penalty is unlikely to lead to meaningful changes in hospital behavior while a higher than optimal full readmission penalty may be inefficient if it shifts the focus of the hospital to “excessive” compliance instead of delivering high-quality, cost-effective care. In the end, the success of this key ACA initiative hinges in our ability to continuously monitor and effectively revise the incentive structure of this and other programs that are designed to work together to reduce hospital readmissions.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Medicare Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. Health Affairs. http://www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=102. Accessed September 20, 2014.

- 2. Rau J. Hospitals face pressure from Medicare to avert readmissions. The New York Times. November 26, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/27/health/hospitals-face-pressure-from-medicare-to-avert-readmissions.html. Accessed September 20, 2014.

- 3. Rau J. Medicare to penalize 2,217 hospitals for excess readmissions. Kaiser Health News, 2012. http://kaiserhealthnews.org/news/medicare-hospitals-readmissions-penalties/. Accessed November 22, 2014.

- 4. Becker GS. Crime and punishment: an economic approach. J Polit Econ. 1968;76 http://ideas.repec.org/a/ucp/jpolec/v76y1968-p169.html. Accessed September 20, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Doyle J. Hospitals Are Punished over Readmissions Barnes-Jewish Gets the Maximum Penalty, Which Cuts Certain Medicare Payments by About $2.2 Million. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: St. Louis Post-Dispatch; 2012:A8. [Google Scholar]

- 6. McKinney M. Preparing for impact. Many hospitals will struggle to escape or absorb readmissions penalty. Mod Healthc. 42:6-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hundreds of UMASS Memorial Medical Center Nurses to Picket Nov. 8 to Call for Safer Staffing Levels to Ensure Quality Patient Care. Worcester, MA: PR Newswire; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Betts S. Pen Bay Medical Center working to cut down high readmission rates after Medicare penalty. Bangor Daily News. August 25, 2012. http://bangordailynews.com/2012/08/25/health/pen-bay-medical-center-working-to-cut-down-high-readmission-rates-after-medicare-penalty/. Accessed November 22, 2014.

- 9. Finding healing: how to reduce hospital readmission rates. Bangor Daily News. September 24, 2012. http://bangordailynews.com/2012/09/24/opinion/editorials/finding-healing-how-to-reduce-hospital-readmission-rates/. Accessed November 22, 2014.

- 10. Messina J. Fix patients the first time: New York hospitals face steep revenue cuts for readmissions that are preventable. Crain’s New York Business. November 11, 2012. http://www.crainsnewyork.com/article/20121111/health_care/311119990/fix-patients-the-first-time. Accessed November 22, 2014.

- 11. Solomon D. Medicare Targets Readmission Costs. The New Hampshire Union Leader. November 17, 2012. http://www.unionleader.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20121118/NEWS12/121119190&template=printart. Accessed November 22, 2014.