Abstract

This study presents the measurement properties of 5 scales used in the Healthcare Provider Cultural Competence Instrument (HPCCI). The HPCCI measures a health care provider’s cultural competence along 5 primary dimensions: (1) awareness/sensitivity, (2) behaviors, (3) patient-centered communication, (4) practice orientation, and (5) self-assessment. Exploratory factor analysis demonstrated that the 5 scales were distinct, and within each scale items loaded as expected. Reliability statistics indicated a high level of internal consistency within each scale. The results indicate that the HPCCI effectively measures the cultural competence of health care providers and can provide useful professional feedback for practitioners and organizations seeking to increase a practitioner’s cultural competence.

Keywords: cultural competence, health care, survey instrument, instrument validation, scales

Background

The requisite that health care providers demonstrate cultural competence is well established.1-5 This need only continues to grow as the demographics within the United States change and diversify.5-8 In addition, cultural competence is critical when addressing disparities in health care and health outcomes.9-11

A growing body of research documents the challenges to delivering culturally competent care to all.6,12 For health care facilities striving to provide the very best patient services, the importance of effective measures of cultural competence and subsequent training and development cannot be overstated. Having culturally skilled health care providers strengthens the provider-patient relationship and leads to the likelihood of more positive health outcomes5,13 and greater patient satisfaction.14

Although research evaluating cultural competence curricular modules and training interventions has been undertaken,15,16 the published literature is lacking in critical areas. First, there is no general consensus on what and how to measure cultural competence. Second, most established instruments have been developed specifically for 1 group of practitioners.7,15,17 In addition, most of the instruments currently in use have not been subject to rigorous psychometric confirmation.7,11 The recent publication of the Cultural Competence Health Practitioner Assessment with 129 items (CCHPA-129) is a noteworthy exception.17

The difficulty of measuring cultural competence among health care providers is evident,18,19 but measurement progress has been demonstrated.3,4,17,19 However, there are very few well-established cultural competence measures specifically designed for a full range of health care providers. The CCHPA-129 provides an important addition, but this instrument focuses primarily on doctors and nurses and a few other clinical professionals.17 An instrument that can be used across providers is needed.

Conceptual Understanding of Cultural Competence

Betancourt et al20 has identified 3 different fundamental philosophical approaches to conceptualizing what is necessary for a health care provider to be culturally competent: (1) the awareness/sensitivity approach, (2) the multicultural/categorical approach, and (3) the cross-cultural approach. The first approach, awareness/sensitivity, argues that the most important aspect of cultural competence is the attitude of the practitioner toward the patient, particularly one from a different culture. Internal characteristics like humility, empathy, curiosity, respect, sensitivity and awareness influence the provider’s attitudes toward a patient’s health care experience.20 In this approach, cultural competence involves a general understanding of the dimensions of culture and their impact on patient-provider interactions.

The multicultural/categorical approach contends that cultures around the world differ significantly in language, customs, beliefs, practices, and sometimes in worldviews. To be culturally competent, health care providers should have at least a basic knowledge of the specifics of these dimensions for the patients they will encounter. This perspective is reflected in cultural reference guides such as the Cultural Sensitivity: A Pocket Guide for Health Care Professionals,21,22 endorsed by the Joint Commission on the accreditation of health care organizations. The Pocket Guide is a spiral handbook that provides culturally specific information for a range of ethnic groups.

The third approach, the cross-cultural approach, asserts that cultural competence is not so much about an individual’s attitudes or specific knowledge of particular cultures as much as it is about process-oriented interpersonal tools and skills. These skills can be used to elicit from patients their perspectives on their illness as well as assist in participatory decision making as part of the provider-patient relationship.20

It is very difficult to expect health care providers to be knowledgeable of the large variety of cultural practices and differences that exist within the field. Furthermore, some experts advise against training about characteristics of specific ethnic/racial groups because such an approach can lead to stereotyping.7,20 For these reasons, the approach toward cultural competence that is pursued in the development of the Healthcare Provider Cultural Competence Instrument (HPCCI) is more consistent with the elements advocated in the first and third approaches.

Much of the conceptual formulation of our model of cultural competence was guided by the integration of active learning and processing combined with behavioral action.5 In addition to these elements, we also recognized the need for personal reflection and analysis in developing one’s cultural competence. Although not well recognized and examined in the existing literature, internal review and examination of the alignment between personal values/beliefs and actions is believed by the authors to be a core component of cultural competence.

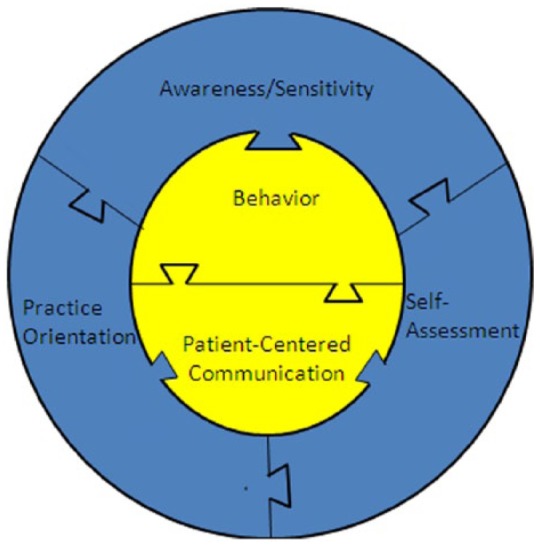

Based on the review of the existing approaches, we identified 4 elements of cultural competence—awareness/sensitivity, behavior, patient-centered communication, and practice orientation for inclusion in the HPCCI. In addition, consistent with the cross-cultural approach,20,22 we included self-assessment of one’s own cultural competence. Our conceptual model (Figure 1) uses the analogy of a jigsaw puzzle.3 Although in the years since this analogy was proposed additional attempts have been made to refine the construct,23-25 the jigsaw analogy is especially useful as it underscores the interconnectedness as well as the importance of the components that make up the construct of cultural competence (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of cultural competency.

As indicated in Figure 1, dimensions of awareness and sensitivity are considered essential pieces of the cultural competence model. Interestingly, in the current analysis, these 2 dimensions loaded onto 1 single factor. This single factor encompasses provider knowledge about, awareness of, and sensitivity to cultural expressions, attitudes, and behaviors of various patient groups, such as differences in language, religion, dietary habits, kinship patterns, and health care practices. It is important to note that this approach is distinct from knowing specifics for each different cultural group that is advocated in the multicultural/categorical approach.20 The challenge for providers within the dimension of awareness and sensitivity is of recognizing group similarities in the context of individual differences. Unfortunately, providers may stereotype patients or apply probabilistic reasoning (ie, “statistically discriminate”) using epidemiological data.26 Because group-based decision making fails to incorporate information about the patient’s unique risk profile or address individual concerns, it may result in suboptimal care for the individual patient.

In addition, central to awareness and sensitivity is the insight that providers’ attributes may be important. A substantial body of research has focused on the role of patient attributes (eg, race, gender, cultural background) in shaping the clinical encounter but less is known about the role of the provider’s attributes.27 This emerging body of scholarship suggests that providers’ social and cultural identities play a role in patient outcomes, including trust, adherence, and satisfaction.28

Included in the current model is the central element of behavior, which Doorenbos and colleagues describe as the “observable outcomes of the diversity experience.”4(p326) The vital nature of this notion is acknowledged in this study by placing behavior at the center of the cultural competence model. Behaviors are viewed as the outward manifestation and demonstration of beliefs and attitudes.

As patient-centered communication is a distinct type or pattern of behavior, this dimension is also placed at the center of the model. Research has focused on patient-centered communication styles in which providers ascertain and incorporate patients’ feelings, beliefs, and expectations into the encounter.29 Studies have found associations between patient-centered communication and patient satisfaction, treatment adherence, and medical outcomes.30-32

The model recognizes a fourth dimension, practice orientation, to capture the attitude toward the power/control relationship between provider and patient in a given provider’s practice.14 The Institute of Medicine defines patient-centered care as “providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.”33 This is in direct contrast to a “doctor knows best” attitude. A patient-centered practice orientation involves awareness of and sensitivity to patient preferences and communication styles, a willingness to adapt to patient preferences, practice behaviors that are customized according to patient needs and values, and responsiveness to individual patient choices and preferences.

Last, the current model identifies the importance of self-assessment as a vital skill for every provider in regard to cultural competence. Self-assessment involves reflecting on one’s, beliefs, values, and attitudes. It is distinct from awareness in that awareness focuses on the patient whereas self-assessment focuses on the provider’s own beliefs, values, and attitudes. There is some evidence that health care providers may hold both conscious and unconscious negative stereotypes about nonwhite patients.34,35 Furthermore, these negative stereotypes may be “habits of the mind” on which providers draw upon especially in circumstances of clinical uncertainty.36 The model suggests that reflection on these issues and active engagement in inclusive practices can further a provider’s cultural competence.

These 5 dimensions were included in the HPCCI: Scale 1, awareness/sensitivity toward cultural competence (11 items)3,4; Scale 2, behaviors demonstrated by health care providers regarding cultural competence (16 items)3,4; Scale 3, patient-centered communication (3 items)29; Scale 4, practice orientation (9 items)14; and Scale 5, self-assessment of cultural competence (9 items). Items from existing instruments were used only if they directly measured the intended dimension and also possessed strong psychometric properties. Items that were used from existing measures were typically modified so that they were applicable to a wide variety of health care providers and not particular to one professional role (eg, nursing). A demographic section and several open-ended questions about previous exposure to cultural competence topics constitute the remaining items of the HPCCI. The authors stayed true to the response format of the previously published scales that were integrated into the present instrument. Consequently, both 5- and 7-response item formats were used.

Method and Descriptive Statistics

As noted earlier, much of the previous literature seeking to establish the validity and reliability of a cultural competence instrument focused on one specific type of health care provider, such as doctors, nurses, or social workers.15 Because 1 of the primary aims of this study was to validate a cultural competence instrument across a broad range of different types of health care providers, broad participation in this study was sought. The sample for the present study was drawn from a large midwestern hospital that offers a comprehensive range of services. The study received institutional review board approval from both the university and the hospital. The hospital’s diversity and inclusion department assisted in recruiting a range of departments that volunteered to have their employees complete the survey. Almost all respondents took the online version of the instrument, with only a small number receiving a hard copy version. As is evident from the information in Table 1, the goal of achieving broad participation from different departments, occupations, and among practitioners with varying levels of education in the hospital was achieved.

Table 1.

Departments, Degrees, and Roles of Survey Respondents.

| No. of participants | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Department | ||

| Neurology | 36 | 14.88 |

| Anesthesia/Radiology | 33 | 13.64 |

| Audiology | 14 | 5.79 |

| Psychiatry | 49 | 20.25 |

| Social Services | 58 | 23.97 |

| Diabetes Center/Endocrinology | 6 | 2.4 |

| Cancer and Blood Disease | 9 | 3.7 |

| The Heart Institute | 4 | 1.65 |

| Other | 24 | 9.92 |

| Blank | 9 | 3.31 |

| ____ | ____ | |

| Total | 242 | 100 |

| Degree | ||

| High school | 5 | 2.07 |

| Associate’s degree | 14 | 5.79 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 45 | 18.6 |

| All masters | 121 | 50 |

| All doctorate | 11 | 4.55 |

| Other | 5 | 2.07 |

| Blank | 41 | 16.94 |

| ____ | ____ | |

| Total | 242 | 100 |

| Role | ||

| Patient care assistant | 11 | 4.55 |

| Audiologist | 12 | 4.96 |

| Social work/counseling | 105 | 43.36 |

| Manager | 3 | 1.23 |

| Mental health specialist | 6 | 2.48 |

| Therapist | 5 | 2.07 |

| Speech language pathologist | 2 | 0.83 |

| Registered nurse | 57 | 23.55 |

| Other | 10 | 4.1 |

| Blank | 31 | 12.81 |

| ____ | ____ | |

| Total | 242 | 100 |

Results

Confirmation of Validity

To establish that the scales had similar psychometric properties to the ones reported in published research, factor analysis for each scale was conducted along with corresponding interitem reliabilities. To be consistent with the validation work conducted by Doorenbos et al,4 this study used principal components factor analysis with oblimin rotation. Table 2 shows a similar pattern of factor loadings for awareness/sensitivity and behavior indicating 2 unique factors. In all cases, except for the first 2 items of the awareness/sensitivity dimension, all of the factor loadings were above .5 and those same 2 items had the lowest factor loadings as reported in the Doorenbos et al study.4 The awareness/sensitivity items have virtually no cross-loadings with the other factor.

Table 2.

Two-Factor Solution Pattern Matrix.

| Awareness/sensitivity | Behavior | |

|---|---|---|

| Scale 1: Awareness and Sensitivitya | ||

| 1. Race is the most important factor in determining a person’s culture | .327 | −.045 |

| 2. People with a common cultural background think and act alike | .220 | .248 |

| 3. Many aspects of culture influence health and health care | .517 | .068 |

| 4. Aspects of cultural diversity need to be assessed for each individual, group, and organization | .628 | .144 |

| 5. If I know about a person’s culture, I do not need to assess their personal preferences for health services | .690 | .029 |

| 6. Spirituality and religious beliefs are important aspects of many cultural groups | .806 | −.186 |

| 7. Individual people may identify with more than 1 cultural group (Original item—Individuals may identify with more than 1 cultural group) | .735 | −.019 |

| 8. Language barriers are the only difficulties for recent immigrants to the United States | .665 | −.149 |

| 9. I understand that people from different cultures may define the concept of “health care” in different ways | .779 | −.162 |

| 10. I think that knowing about different cultural groups helps direct my work with individuals, families, groups, and organizations | .703 | .144 |

| 11. I enjoy working with people who are culturally different from me | .528 | .085 |

| Scale 2: Behaviorb | ||

| 12. I include cultural assessment when I do client or family evaluations | −.017 | .741 |

| 13. I seek information on cultural needs when I identify new clients and families in my practice | .009 | .790 |

| 14. I have resource books and other materials available to help me learn about clients and families from different cultures | −.121 | .652 |

| 15. I use a variety of sources to learn about the cultural heritage of other people | −.122 | .691 |

| 16. I ask clients and families to tell me about their own explanations of health and illness | −.211 | .808 |

| 17. I ask clients and families to tell me about their expectations for health services (Original item—I ask clients and families to tell me about their expectations for care) | −.124 | .741 |

| 18. I avoid using generalizations to stereotype groups of people | .442 | .453 |

| 19. I recognize potential barriers to service that might be encountered by different people | .323 | .625 |

| 20. I act to remove obstacles for people of different cultures when I identify such obstacles | .343 | .652 |

| 21. I remove obstacles for people of different cultures when clients and families identify such obstacles to me (Original item—I act to remove obstacles for people of different cultures when clients and families identify such obstacles to me) | .385 | .468 |

| 22. I welcome feedback from clients and their families about how I relate to others with different cultures (Original item—I welcome feedback from clients about how I relate to others with different cultures) | .426 | .522 |

| 23. I welcome feedback from coworkers about how I relate to others with different cultures | .502 | .470 |

| 24. I find ways to adapt my services to my clients and their families’ preferences (Original item—I find ways to adapt my services to client and family cultural preferences) | .384 | .552 |

| 25. I document cultural assessments | −.093 | .676 |

| 26. I document the adaptations I make with clients and their families (Original item—I document the adaptations I make with clients and families) | −.009 | .738 |

| 27. I learn from my coworkers about people with different cultural heritages | .146 | .632 |

Note. For all questions, respondents were also always given response options of no opinion/not sure or not applicable.

Scale 1: 7-item scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

Scale 2: 7-item scale ranging from never to always.

The second factor, behavior, was clearly differentiated from the awareness/sensitivity factor, with all factor loadings being above .45. Some cross-loadings from a few of the items of the behavior dimension were identified but only 1 was above the .5 level. The item loadings were found to be consistent with and in many cases actually stronger than the results reported by Doorenbos et al4 in their study of nurses.

The remainder of the survey consists of 2 other previously developed scales and 1 additional scale developed for use in this study. Table 3 shows the factor loadings for the remaining 3 dimensions of cultural competence using a 3-factor solution. To remain consistent across the analyses, principal components factor analysis with oblimin rotation was used. The patient-centered communication scale consists of 3 items developed by Cooper and colleagues.29 All 3 items loaded at the .7 level or higher and showed almost no cross-loadings.

Table 3.

Three-Factor Solution Pattern Matrix.

| Patient-centered communication | Practice orientation | Self-assessment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scale 3: Patient-Centered Communicationa | |||

| 28. When there are a variety of treatment options, how often do you give the client and their family a choice when making a decision? | .891 | .055 | −.046 |

| 29. When there are a variety of treatment options, how often do you make an effort to give the client and their family control over their treatment? | .886 | −.040 | .102 |

| 30. When there are a variety of treatment options, how often you ask the client and their family to take responsibility for their treatment? | .721 | .111 | −.074 |

| Scale 4: Practice Orientationb | |||

| 31. The health care provider is the one who should decide what gets talked about during a visit | −.014 | .770 | −.091 |

| 32. It is often best for the client and their family that they do not have a full explanation of the client’s medical condition | .025 | .634 | .034 |

| 33. The client and their family should rely on their health care providers’ knowledge and not try to find out about their condition(s) on their own | .033 | .833 | −.179 |

| 34. When health care providers ask a lot of questions about a client and their family’s background, they are prying too much into personal matters | .033 | .506 | .129 |

| 35. If health care providers are truly good at diagnosis and treatment, the way they relate to client and their family is not that important | .039 | .482 | .357 |

| 36. The client and their family should be treated as if they are partners with the health care provider, equal in power and status | .167 | .442 | .153 |

| 37. When the client and their family disagree with their health provider, this is a sign that the health care provider does not have the client and their family’s respect and trust | −.195 | .318 | .167 |

| 38. A treatment plan cannot succeed if it is in conflict with a client and their family’s lifestyle or values | .004 | .455 | .008 |

| 39. It is not that important to know a client and their family’s culture and background to treat the client’s illness | −.071 | .164 | .340 |

| Scale 5: Self-Assessmentc | |||

| 40. As a health care provider, I understand how to lower communication barriers with clients and their families | .039 | −.099 | .587 |

| 41. I have a positive communication style with clients and their families | −.040 | −.092 | .813 |

| 42. As a health care provider, I am able to foster a friendly environment with my clients and their families | −.024 | .041 | .793 |

| 43. I attempt to demonstrate a high level of respect for clients and their families | −.043 | .105 | .826 |

| 44. As a health care provider, I consistently assess my skills as I work with diverse groups of clients and their families | .030 | −.113 | .715 |

| 45. I attempt to establish a genuine sense of trust with my clients and their families | −.010 | .097 | .791 |

| 46. I make every effort to understand the unique circumstances of each client and her or his family | .003 | .033 | .805 |

| 47. I value the life experience of each of my clients and their families | .047 | .142 | .751 |

| 48. The use of effective interpersonal skills is very important in working with my clients and their families | .018 | .137 | .794 |

Note. For all questions, respondents were also always given response options of not applicable.

Scale 3: 5-item scale ranging from never to very often.

Scale 4: 5-item scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

Scale 5: 5-item scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

A fourth factor is practice orientation, based on Krupat et al14 Although this scale was originally designed to capture practice orientation among physicians, the current study applied this same concept to a much broader range of health care providers. To maintain consistency with the original construction of these items, the wording and response categories were maintained as used in Krupat et al14 These items all loaded on the fourth factor with loadings of greater than .4, except for 2 items. None of the items for this domain loaded on any of the other scales.

Finally, a scale not previously found in the literature, self-assessment, was developed for this study. The self-assessment scale consists of nine items. All elements loaded on a single factor with factor loadings all over .7 except for 1 item. In addition, no cross-loadings were demonstrated. Overall, the assessment of the validity of the scales produced generally strong results and indicated that the scales served as genuine and recognizable components within the cultural competence construct.

Confirmation of Reliability

To measure the reliability of the items within each scale, a Cronbach’s alpha was calculated. For each of the 5 scales within this survey, the reliability coefficients were at levels indicative of a high degree of internal consistency. The following alphas were calculated: awareness/sensitivity, .791; behavior, .926; patient-centered communication, .764; practice orientation, .722; and self-assessment, .920.

Discussion

Managers often say that one cannot manage what one cannot measure. Given the consensus among health care leaders and researchers on the growing importance of cultural competence among health care providers, it is vital that effective ways to measure this important construct exist. One of the central motivating questions for this study was whether the concept of cultural competence is one that is universal and thus measurable across different health care providers or if it focuses more narrowly on specific sets of behaviors or knowledge that would be more appropriately measured separately by occupational groupings. If what it means to be culturally competent differs across the wide variety of health care professionals, then the measurement aspect of the task alone could stifle progress in developing culturally competent health care providers. Furthermore, a finding that measurement of cultural competence must be done separately across health care professionals would imply that said professionals need different cultural competence training as well, further challenging health care administrators’ task of increasing cultural competence of their patient contact staff.

Therefore, the health care industry cannot hope to train a broad range of professionals to be more culturally competent if broadly applicable measurement instruments do not exist. If separate, position-based, measures of cultural competence are used, some professions with small numbers of employees are sure to be left out. Moreover, the administrative burden of implementing multiple assessments could well impede effectively measuring this important construct. The HPCCI represents a step toward the important goal of establishing a measure of cultural competence, viewed as a set of critical dimensions, which is relevant to a wide variety of health care providers.

The finding that the current combination of scales can be used across a wide variety of health care providers is very encouraging. Having a valid, reliable, and generalizable measure of cultural competence is an important step in establishing a rigorous empirical connection between cultural competence and intended health care outcomes.

Limitations

This study has established the usefulness of the HPCCI across a variety of health care practitioners. However, the results are based on 1 hospital with employees who volunteered to participate in cultural competence training. The sampling strategy used in the study was a convenience sample, one driven by organizational realities. The hospital hosting this study was embarking on a cultural competence training initiative for a broad spectrum of nonphysician health care providers across many different departments within the institution. Participation in the program was driven by departmental leadership agreeing to release time for the employees to attend training. To assess the effectiveness of training such a diverse group with the same course content, it was necessary to develop and validate an instrument that could capture the level of cultural competence for all participants. This convenience sample limits the study’s generalizability. Likewise, the sample did not include physicians. Significantly, participants in the study included a broad range of health care providers with considerable patient contact. Future research with this instrument needs to be conducted in other health care settings with wider representation of roles.

Another limitation is that all of the scales are self-reports. This limitation is particularly of concern for the measure of behavior, a central component of cultural competence. Having outsider recorders for behavior verification is ideal. However, the cost and practical obstacles of such an endeavor puts this method beyond the ability of most health care institutions. As such, a psychometrically sound self-reported measure of behavior is a useful tool.

Another concern is the likelihood of social desirability bias.7 Social desirability bias may have resulted in respondents inflating their proficiencies. Interestingly, Paez et al37 found a statistically significant correlation between physician self-report measures of cultural competence and their patients’ satisfaction and willingness to share more information with the doctor. Consistent with this finding, we believe that self-report measures are a useful tool. These measures could be supplemented with observations and other more direct measures as time and other resources become available.

A final limitation is the use of response categories “strongly agree” to strongly disagree” . A growing body of research suggests that the agree-disagree (AD) response categories may be subject to potential for acquiescence bias and enhanced cognitive burden.39 However, a recent study examined systematic measurement error related to the AD format and concluded that “AD items are on par or better than CS (construct specific) worded items.”38 (p2) As the article by Revilla et al notes, “these scales [AD] remain popular with researchers due to practical considerations (e.g., ease of item preparation, speed of administration, and reduced administration costs).”40 (p73)

Despite the aforementioned limitations, the findings suggest that the HPCCI is an effective and psychometrically supported instrument that measures cultural competence for a broad range of health care professionals. The HPCCI can be used as a whole or one or more of the scales may be used for specific investigation. This instrument can be used to evaluate training programs to increase health care practitioners’ cultural competence. A valid, comprehensive cultural competence instrument that is relevant and appropriate for a variety of professional groups can greatly facilitate a health care organization’s efforts to measure and enhance the cultural competence of its employees.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors would like to acknowledge grant support from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, and Farmer School of Business and the Department of Management at Miami University.

References

- 1. Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE. Cultural Competence in Healthcare: Emerging Frameworks and Practical Approaches. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brach C, Fraserirector I. Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? a review and conceptual model. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57:181-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Doorenbos AZ, Schim SM. Cultural competence in hospice. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2004;21:28-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Doorenbos AZ, Schim SM, Benkert R, Borse NN. Psychometric evaluation of the cultural competence assessment instrument among healthcare providers. Nurs Res. 2005;54:324-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schim SM, Doorenbos AZ. A three-dimensional model of cultural congruence: framework for intervention. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2010;6:256-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Long JA, Chang VW, Ibrahim SA, Asch DA. Update on the health disparities literature. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:805-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gozu A, Beach MC, Price EG, et al. Self-administered instruments to measure cultural competence of health professionals: a systematic review. Teach Learn Med. 2009;19:180-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare. Washington, DC: National Academic Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lasser KE, Murillo J, Lisboa S, et al. Colorectal cancer screening among ethnically diverse, low-income patients: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:906-912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Philis-Tsimikas A, Fortmann A, Lleva-Ocana L, et al. Peer-led diabetes education programs in high-risk Mexican Americans improve glycemic control compared with standard approaches: a Project Dulce promotora randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1926-1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Saha S, Korthuis PT, Cohn JA, Sharp VL, Moore RD, Beach MC. Primary care provider cultural competence and racial disparities in HIV care and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:622-629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Benkert R, Tanner C, Guthrie B, Oakley D, Pohl J. Cultural competence in nurse practitioner students: a consortium’s experience. J Nurs Educ. 2005;44:225-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Giger J, Davidhizar RE, Purnell L, Harden JT, Phillips J, Strickland O. American Academy of Nursing Expert Panel report developing cultural competence to eliminate health disparities in ethnic minorities and other vulnerable populations. J Transcult Nurs. 2007;18:95-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Krupat E, Rosenkranz SL, Yeager CM, Barnard K, Putnam SM, Inui TS. The practice orientations of physicians and patients: the effect of doctor-patient congruence on satisfaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;39:49-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Beach MC, Price EG, Gary TL, et al. Cultural competence: a systematic review of health care provider educational interventions. Med Care. 2005;43:356-373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Prescott-Clements L, Schuwirth L, van der Vleuten C, et al. The cultural competence of health care professionals: conceptual analysis using the results from a national pilot study of training and assessment. Eval Health Prof. 2013;36:191-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harris-Haywood S, Goode T, Gao Y, et al. Psychometric evaluation of a cultural competency assessment instrument for health professionals. Med Care. 2014;52:e7-e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schim SM, Doorenbos AZ, Miller J, Benkert R. Development of a cultural competence assessment instrument. J Nurs Meas. 2003;11:29-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kumas-Tan Z, Beagan B, Loppie C. Measures of cultural competence: examining hidden assumptions. Acad Med. 2007;82:548-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Ananeh-Firempong O. Defining cultural competence: a practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Rep. 2003;118(4):293-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Galanti GA. Cultural Sensitivity: A Pocket Guide for Health Care Professionals. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: Joint Commission Resources; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Paez KA, Allen JK, Carson KA, Cooper LA. Provider and clinic cultural competence in a primary care setting. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:1204-1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Betancourt JR. Cultural competence and medical education: many names, many perspectives, one goal. Acad Med. 2006;81:499-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Saha S, Beach MC, Cooper LA. Patient centeredness, cultural competence and healthcare quality. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100:1275-1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tucker CM, Herman KC, Ferdinand LA, Beato C, Adams D, Cooper LA. Providing patient-centered culturally sensitive healthcare: a formative model. Couns Psychol. 2007;35(5):679-705. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Balsa AI, McGuire TG, Meredith LS. Testing for statistical discrimination in healthcare. Health Serv Res. 2005;40:227-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Flocke SA, Gilchrist V. Physician and patient gender concordance and the delivery of comprehensive clinical preventive services. Med Care. 2005;43:486-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goode TD, Dunne MC, Bronheim SM. The Evidence Base for Cultural and Linguistic Competency in Health Care. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:907-915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Epstein RM, Franks P, Fiscella K, Shields CG, Meldrum SC, Kravitz RL. Measuring patient-centered communication in patient-physician consultations: theoretical and practical issues. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:1516-1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rao JK, Weinberger M, Kroenke K. Visit-specific expectations and patient-centered outcomes: a literature review. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:1148-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Williams S, Weinman J, Dale J. Doctor-patient communication and patient satisfaction: a review. Fam Pract. 1998;15:480-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Institute on Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=10027. Published 2013. Accessed September 29, 2013.

- 34. van Ryn M, Burgress D, Malat J, Griffin J. Physicians’ perceptions of patients’ social and behavioral characteristics and race disparities in treatment recommendations for men with coronary artery disease. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:351-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Green AR, Carney DR, Pallin DJ. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for black and white patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1231-1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gerrity MS, White KP, DeVellis RF, Dittus RS. Physicians’ reactions to uncertainty: refining the constructs and scales. Mot Emot. 1995;19:175-191. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Paez KA, Allen JK, Beach MC, Carson KA, Cooper LA. Physician cultural competence and patient ratings of the patient-physician relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:495-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wilson DC, Davis D, Dykema J, Schaeffer NC. Response scales and the measurement of racial attitudes: agree-disagree versus construct specific formats. Conference Papers—American Political Science Association, August 2013; 1-25. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Saris WE, Revilla M, Krosnick JA, Shaeffer EM. Comparing questions with agree/disagree response options to questions with item-specific response options. Surv Res Methods. 2010;4:61-79. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Revilla MA, Saris WE, Krosnick JA. Choosing the number of categories in agree–disagree scales. Sociol Methods Res. 2014;43:73-97. [Google Scholar]