ABSTRACT

Introduction

The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of GBS colonization in pregnant women in a public health service.

Methods

A study of 496 pregnant women at 35-37 gestational weeks was conducted from September 2011 to March 2014 in 21 municipalities of the 18th Health Region of Paraná State. Vaginal and anorectal samples of each woman were plated on sheep blood agar, and in HPTH and Todd-Hewitt enrichment broths.

Results

Of the 496 pregnant women, 141 (28.4%) were positive for GBS based on the combination of the three culture media with vaginal and anorectal samples. The prevalence was 23.7% for vaginal samples and 21.9% for anorectal ones. Among the variables analyzed in this study, only urinary infection was a significant factor (0.026) associated with GBS colonization in women.

Conclusions

Based on these results, health units should performs universal screening of pregnant women and hospitals should provide adequate prophylaxis, when indicated.

Keywords: Streptococcus agalactiae., Colonization, Urinary infections, Pregnant women, Public health

INTRODUCTION

Maternal colonization by Group B Streptococcus (GBS) is the main risk factor for neonatal GBS infection. GBS or Streptococcus agalactiae may be part of the human microbiota, mainly colonizing the gastrointestinal and genitourinary tract 1 . About 50 to 75% of newborns exposed to intravaginal GBS become colonized, and 1 to 2% of newborns of carrier mothers will develop early-onset invasive disease 1 , 2 . In the mother, GBS may cause abortion, urinary infection, preterm birth, chorioamnionitis or puerperal endometritis 3 .

A hypothesis of this occurrence might be the hormonal changes occurring during the gestational period and the consequent microbiota imbalance, increasing the chances of GBS infections which can trigger maternal and child complications 1 .

In Brazil, some studies have shown different colonization rates by GBS (24.5%, 16.6%, 27.6%) 4 - 6 . In other countries researches have also shown different rates (3.3% to 22.76%) 7 - 9 .

Variations in prevalence of GBS colonization in women found in literature can be attributed to both, differences in the characteristics of the studied populations and the employed bacteriological methodologies 2 .

Samples for culture obtained up to four weeks before delivery have greater sensitivity and specificity to identify maternal colonization by GBS 10 . Studies have shown a high rate of transmission to newborns during childbirth, as well as increased infection and neonatal mortality rate. Given this pathogenic and relatively frequent role of vaginal colonization by GBS, screening strategies should be adopted between the 35th and 37th gestational weeks 11 .

GBS screening in pregnant women and antimicrobial prophylaxis (when indicated) may reduce neonatal morbidity and mortality; therefore, future studies should evaluate the effects and costs of introducing a universal infection screening program.

In this sense, this study aimed to verify the prevalence of Streptococcus agalactiae colonization in pregnant women from public health services.

METHODS

A cross-sectional study was conducted in 21 municipalities belonging to the 18th Regional Health Department of Paraná State, Brazil. The number of live births in this region in 2010 was 2,848. The sample was calculated using Epidata software by the population proportion method, with the proportion of the expected outcome being 50%, a sample error of 4%, and a 95% confidence level. Thus, the calculated sample was 496 individuals. The following calculation was used for stratification of the number of pregnant women in each municipality: minimum size of the previously calculated/total sample of live births from the 18th Regional Health Department multipled by the total number of live births from each municipality (496/2,848 x number of live births from each municipality).

Inclusion criteria of the study were: pregnant women with gestational age between 35 and 37 weeks, determined from the date of the last menstruation period (DLM) or by the fetal ultrasound performed in the first trimester of gestation. All participants signed the informed consent form. A guardian signed the informed consent form when pregnant women were under the age of 18. Pregnant women who had been using antimicrobials in the last seven days or who used vaginal ointment at the time of collection were excluded from the study.

Data collection was performed by the researcher between September 2011 and March 2014. When tests were scheduled, the researcher went to the municipalities to collect the biological samples and to help women to fill out a form that contained the following information: pregnant woman’s identification, ethnicity, age, educational level, marital status, family income, number of pregnancies, current gestational data, gestational age, occurrence of urinary tract infection during the current gestation, sexually transmitted disease prior to or during the current gestation, prior miscarriage and number of sexual partners.

Biological samples were collected from the distal third of the vagina by the introduction of sterile swabs through the vaginal introitus without speculum. This procedure was repeated three times and the samples were labeled as vaginal swab 1, 2, and 3. Anorectal samples were collected by the introduction of sterile swabs through the anorectal region three times and samples were labeled as anorectal swabs 1, 2, and 3. Vaginal swab 1 and anorectal swab 1 were cultured in HPTH culture medium (Hitchens - Pike - Todd - Hewitt) supplemented with 100 μL of sterile defibrinated sheep blood (Laborclin, São José dos Pinhais, Paraná, Brazil) and incubated at 35 °C for 18 to 24 h. After this period of incubation, the sample was subcultured into blood agar and incubated at 35 °C for 24 to 48 h. Vaginal swab 2 and anorectal swab 2 were cultured in Todd-Hewitt culture medium (Himedia, Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil) supplemented with 8 μg/mL of gentamicin (Inlab, São Paulo, Brazil) and 15 μg/mL of nalidixic acid (Inlab, São Paulo, Brazil), and incubated at 35 °C for 18 to 24 h. The material was then subcultured into blood agar (Himedia, Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil) and incubated at 35 °C for 24 to 48 h. Vaginal swab 3 and anorectal swab 3 were immediately cultured in 1/3 of blood agar medium (Himedia, Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil) and incubated at 35 °C for 18 to 24 h.

Streptococcus identification was carried out in the Clinical Bacteriology laboratory of the Department of Clinical Analysis and Biomedicine (DAB) of the Universidade Estadual de Maringá. Colonies that were suggestive of GBS (beta- and non-hemolytic) were subjected to microscopy (Gram stain), biochemical identification (catalase, bile esculin, and hippurate hydrolysis) and latex agglutination using a streptococcal grouping kit (Oxoid, Hampshire, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Data were entered into the Microsoft Office Excel 2007 program and analyzed using the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) version 7.3. The chi-squared test was used to analyze the relationship between the values with a 5% significance level (p=0.05). Results were presented in tables, and discussed according to the implemented theoretical framework.

The research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Universidade Estadual de Maringá, Process Nº 236/2011.

RESULTS

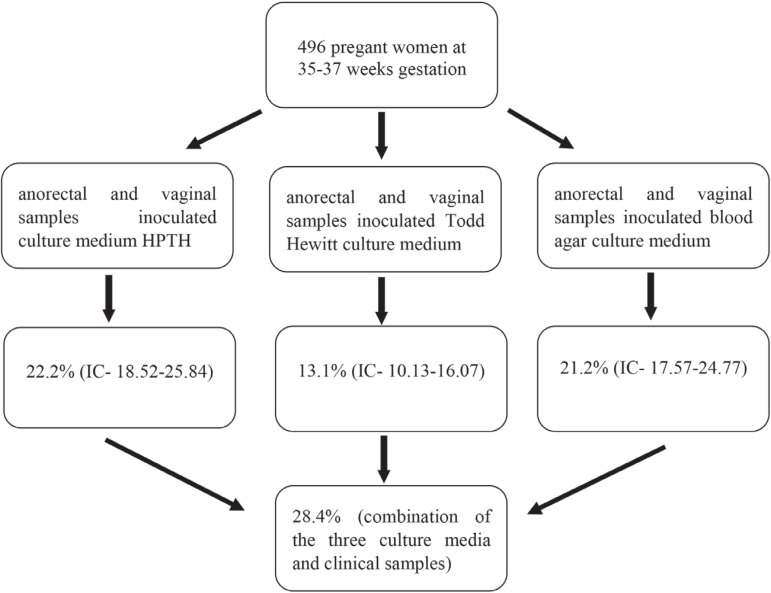

Of the 496 pregnant women at 35-37 gestational weeks who participated in the study, 141 (28.4%) were positive for GBS based on the combination of the three culture media results from the two clinical specimens. The detected GBS colonization rate was 22.2% (IC- 18.52 -25.84) for HPTH medium, 21.2% (IC- 17.57- 24.77) for SBA, and 13.1% (IC- 10.13 – 16.07) for Todd-Hewitt enrichment broth (Figure 1). The prevalence for vaginal samples was 23.7%, and 21.9% for anorectal samples.

Figure 1. – Flowchart of culture results, from vaginal and anorectal specimens, in pregnant women at 35-37 gestational weeks to detect Streptococcus agalactiae by Hitchens-Pike-Todd-Hewitt (HPTH), Todd-Hewitt enrichment broth and sheep blood agar (SBA) culture media.

Regarding socio-demographic data, 72.8% of pregnant women were white, 88.1% had one partner, and the age group ranged from 14 to 41 years old with an average of 24.8 years. Evaluation of the educational level followed the functional illiteracy criterion adopted by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), showing that 65.1% of women had studied more than eight years, and 19.4% had monthly family income of up to two minimum wages (Table 1). No statistically significant relationship was observed between socio-demographic data and GBS colonization (Table 2).

Table 1. - Distribution of pregnant women according to socio-demographic variables, 18th Regional Department of Health, 2015.

| Variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 361 | 72.8 |

| Non-White | 135 | 27.2 |

| Marital Status / Relationship Status | ||

| With a partner | 437 | 88.1 |

| Without a partner | 59 | 11.9 |

| Current age | ||

| < 20 years | 135 | 27.2 |

| ≥ 20 years | 361 | 72.8 |

| Educational level | ||

| Up to 8 years of study | 173 | 34.9 |

| More than 8 years of study | 323 | 65.1 |

| Family Income | ||

| Up to 1 minimum wage | 400 | 80.6 |

| Up to 2 minimum wages | 96 | 19.4 |

|

| ||

| TOTAL | 496 | 100 |

Table 2. - Distribution of pregnant women colonized by GBS according to socio-demographic variables, 18th Regional Department of Health, 2015.

| Variables | n | % | IC 95% | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | 0.635 | |||

| White | 100/361 | 27.70 | 22.95 – 32.46 | |

| Non-White | 41/135 | 30.37 | 22.24 – 38.50 | |

| Marital Status / Relationship Status | 0,485 | |||

| With a partner | 127/437 | 29.06 | 24.69 – 33.43 | |

| Without a partner | 14/59 | 23.73 | 12.06 – 35.43 | |

| Current age | 0,520 | |||

| < 20 years | 35/135 | 25.93 | 18.16 – 33.69 | |

| ≥ 20 years | 106/361 | 29.36 | 24.53 – 34.20 | |

| Educational level | 0,947 | |||

| Up to 8 years of study | 50/173 | 28.90 | 21.86 – 35.95 | |

| More than 8 years of study | 91/323 | 28.17 | 23.11 – 33.23 | |

| Family Income | 0,069 | |||

| Up to 1 minimum wage | 106/400 | 26.50 | 22.05 – 30.95 | |

| Up to 2 minimum wages | 35/96 | 36.46 | 26.31 – 46.61 |

Regarding the gynecological-obstetric characterization, the majority was of multiparous (59.7%) with gestational age of 35th week (43.1%). The age of first gestation ranged from 12 to 39 years; 27.2% were less than 19 years old; 84.7% had no previous abortion; 3.0% reported a sexually transmitted disease in life (among those cited were: HIV, Trichomoniasis, HPV, Syphilis, and Chlamydia); 40.1% reported urinary tract infection in the current pregnancy; and 40.0% had only one sexual partner in life. The predominant type of delivery was vaginal (59.9%) (Table 3). There was only a statistically significant relationship between urinary infection during the current gestation and GBS colonization in women (0.026) (Table 4).

Table 3. - Distribution of pregnant women according to gynecological and obstetric variables, 18th Regional Department of Health, 2015.

| Variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gestational Age | ||

| 35 | 214 | 43.1 |

| 36 | 138 | 27.8 |

| 37 | 144 | 29.1 |

| Number of pregnancies | ||

| Primiparous | 200 | 40.3 |

| Multiparous | 296 | 59.7 |

| Sexually Transmitted Disease | ||

| Yes | 15 | 3.0 |

| No | 481 | 97.0 |

| Urinary Infection during Pregnancy | ||

| Yes | 199 | 40.1 |

| No | 297 | 59.9 |

| Type of delivery* | ||

| Vaginal | 173 | 59.9 |

| Cesarean | 116 | 40.1 |

| Number of partners | ||

| 1 | 198 | 40.0 |

| 2 | 113 | 22.8 |

| 3 or more | 185 | 37.2 |

| Use of condom | ||

| Yes | 23 | 4.6 |

| No | 473 | 95.4 |

| Abortion | ||

| Yes | 76 | 15.3 |

| No | 420 | 84.7 |

|

| ||

| TOTAL | 496 | 100 |

* The values do not total 496 pregnant women because primiparous and abortions were excluded from this sum, because the risk factor for GBS is for women who have had childbirth, regardless of the route.

Table 4. - Distribution of pregnant women colonized by GBS according to gynecological and obstetric variables, 18th Regional Department of Health, 2015.

| Variables | n | % | IC% | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational Age | 0.387 | |||

| 35 | 54/214 | 25.23 | 19.18 - 31.29 | |

| 36 | 43/138 | 31.16 | 23.07 - 39.25 | |

| 37 | 44/144 | 30.56 | 22.68 - 38.43 | |

| Number of pregnancies | 0.783 | |||

| Primiparous | 55/200 | 27.5 | 21.06 - 33.94 | |

| Multiparous | 86/296 | |||

| Sexually Transmitted Disease | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 4/15 | 26.67 | 7.78 - 55.1 | |

| No | 137/481 | 28.48 | 24.34-32.62 | |

| Urinary Infection during Pregnancy | 0.026 | |||

| Yes | 68/199 | 34.17 | 27.33-41.01 | |

| No | 73/297 | 24.58 | 19.51-29.64 | |

| Type of delivery* | 0.963 | |||

| Vaginal | 52/173 | 30.06 | 22.94-37.18 | |

| Cesarean | 36/116 | 31.03 | 22.18-39.88 | |

| Number of partners | 0.961 | |||

| 1 | 55/198 | 27.78 | 21.28-34.27 | |

| 2 | 33/113 | 29.20 | 20.38-38.03 | |

| 3 or more | 53/185 | 28.65 | 21.86-35.43 | |

| Use of condom | 0.649 | |||

| Yes | 8/23 | 34.78 | 13.14-56.42 | |

| No | 133/473 | 28.12 | 23.96-32.28 | |

| Abortion | 0.977 | |||

| Yes | 21/76 | 27.63 | 16.92-38.34 | |

| No | 120/420 | 28.57 | 24.13-33.01 |

* The values do not total 496 pregnant women because primiparous and abortions were excluded from this sum, because the risk factor for GBS is for women who have had childbirth, regardless of the route.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the frequency of colonization by S. agalactiae was 28.4%, and it was higher than that found in national studies conducted in a Primary Health Units (UBS) in São Paulo (17.4%), as well as in private (15.2%) and public (22.5%) centers in Rio Grande do Sul 10 , 12 , 13 . Some studies performed in other countries have also found lower frequencies, ranging from 2.3% to 8.3% 14 - 16 .

Prevalence variations of GBS colonization in women found in the literature can be attributed to both, differences in the characteristics of the studied populations (such as age, parity, ethnic group, socioeconomic level and geographical location) and to the employed diagnostic methods 14 .

According to CDC, the use of vaginal/rectal swabs improves GBS isolation by 40%, compared with vaginal specimens alone 17 . Marconi et al. 18 collected material from the vaginal introitus, the lateral recess of the vagina and the perianal region. Among the patients with positive culture, 28.1% were positive at only one collection site, 24.2% at two sites and 47.5% at the three sites cited. In the present study, the vaginal colonization rate was 23.7%, and the anorectal rate was 21.9%. When the two sites were combined, the rate was of 28.4%. Thus, cultures performed with samples from more than one site allow the identification of the site from which more GBS can be recovered, resulting in more reliable results.

No significant association was found in this study regarding socio-demographic data and GBS colonization in women. The same can be observed in the work of other researchers 7 , 15 .

The Center for Disease Control (CDC) 19 recommends a gestational age from the 35th week for sample collection because there is a greater risk of vertical transmission in this period. Colonization of pregnant women at the beginning of gestation has no predictive value regarding neonatal infection. This period was determined because it is considered that GBS colonization can be transient, and it is relevant to know the colonization frequency in the period near birth 20 . In the present study, the majority (43.1%) of women was in the 35th week of gestation, and 38.3% of these were colonized by GBS; however, the gestational age at the time of collection was not associated with the presence of GBS (p = 0.387).

Socio-demographic and clinical factors were not associated with GBS colonization, but urinary infection at some point in the current gestation was a significant risk factor. A similar result was found in the study by Mitima et al. 21 (p <0.05), but it differs from the study by Kruk et al. 20 , in which urinary infection was not significant in GBS colonization in women (p = 0.191). It was not possible to identify which pathogen caused urinary tract infections in pregnant women because this variable was not reported by the interviewees. It is known that urinary tract infections can cause complications during the gestation period.

CONCLUSION

Although screening is affordable and sample collection is simple, GBS culture is still not routinely performed during prenatal care in many cities in the country. Public policies in the area of maternal and child health have been organized in recent decades focusing on expanding and improving the quality of obstetric care. However, a lack of information regarding the occurrence of infection may be responsible for the lack of attention given by responsible agencies, both in the prenatal screening and in the correct prophylaxis at the time of delivery of colonized women.

Since pregnant women colonization was shown to be frequent in this study, and GBS can cause neonatal sepsis, miscarriage and endometritis, it is recommended that health units perform universal screening of pregnant women and that hospitals perform prophylaxis, when indicated.

Footnotes

FUNDING

This work was partially supported by Araucaria Foundation for the Support of Scientific and Technological Development of the Paraná State, Brazil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nogueira IM, Gonçalves SC, Carreiro VM, Santos A. Estreptococos B como causa de infecções em mulheres grávidas: revisão de literatura. Rev Uningá Rev. 2013;16:36–41. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pogere A, Zoccoli CM, Tobouti NR, Freitas PF, d’Acampora AJ, Zunino JN. Prevalência da colonização pelo estreptococo do grupo B em gestantes atendidas em ambulatório de pré-natal. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2005;27:174–180. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamedi A, Akhlaghi F, Seyedi SJ, Kharazmi A. Evaluation of group B Streptococci colonization rate in pregnant women and their newborn. Acta Med Iran. 2012;50:805–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaves M, Júnior, Pádua RA, Campanerut PA, Pelloso SM, Carvalho MD, Siqueira VL, et al. Preliminary evaluation of Hitchens-Pike-Todd-Hewitt medium (HPTH) for detection of group B Streptococci in pregnant women. J Clin Lab Anal. 2010;24:403–406. doi: 10.1002/jcla.20419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bastos AN, Bastos RV, Dias VC, Bastos LQ, Souza RC, Bastos VQ. Streptococcus agalactiae em gestantes: incidência em laboratório clínico de Juiz de Fora (MG) – 2007 a 2009. HU Rev. 2012;38:129–134. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nomura ML, Passini R, Júnior, Oliveira UM, Calil R. Colonização materna e neonatal por estreptococo do grupo B em situações de ruptura pré-termo de membranas e no trabalho de parto prematuro. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2009;31:397–403. doi: 10.1590/s0100-72032009000800005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hadavand S, Ghafoorimehr F, Rajabi L, Davati A, Zafarghandi N. Frequency of group B Streptococcal colonization in pregnant women aged 35-37 weeks in clinical centers of Shahed University, Tehran, Iran. Iran J Pathol. 2015;10:120–126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ezeonu IM, Agbo MC. Incidence and anti-microbial resistance profile of Group B Streptococcus (GBS) infection in pregnant women in Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2014;8:91–95. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Javanmanesh F, Eshraghi N. Prevalence of positive recto-vaginal culture for Group B Streptococcus in pregnant women at 35-37 weeks of gestation. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2013;27:7–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Função JM, Narchi NZ. Pesquisa do estreptococo do Grupo B em gestantes da Zona Leste de São Paulo. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2013;47:22–29. doi: 10.1590/s0080-62342013000100003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taminato M, Fram D, Torloni MR, Belasco AG, Saconato H, Barbosa DA. Rastreamento de Streptococcus do grupo B em gestantes: revisão sistemática e metanálise. Rev Lat Am Enferm. 2011;19:1470–1478. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692011000600026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiss FS, Rossato JS, Graudenz MS, Gutierrez LL. Prevalência da colonização por Streptococcus agalactiae em uma amostra de mulheres grávidas e não grávidas de Porto Alegre, Estado do Rio Grande do Sul. Sci Med. 2013;23:169–174. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Senger FR, Alves IA, Pellegrini DC, Prestes DC, Souza EF, Corte ED. Prevalência da colonização por Streptococcus agalactiae em gestantes atendidas na rede pública de saúde de Santo Ângelo/RS. Rev Epidemiol Control Infec. 2016;6:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharmila V, Joseph NM, Arun Babu T, Chaturvedula L, Sistla S. Genital tract group B streptococcal colonization in pregnant women: a South Indian perspective. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2011;5:592–595. doi: 10.3855/jidc.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim EJ, Oh KY, Kim MY, Seo YS, Shin JH, Song YR, et al. Risk factors for group B Streptococcus colonization among pregnant women in Korea. Epidemiol Health. 2011;33:e2011010. doi: 10.4178/epih/e2011010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petersen KB, Johansen HK, Rosthoj S, Krebs L, Pinborg A, Hedegaard M. Increasing prevalence of group B streptococcal infection among pregnant women. A4908Dan Med J. 2014;61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Laboratory practices for prenatal group B streptococcal screening seven states, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:506–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marconi C, Rocchetti TT, Rall VL, Carvalho LR, Borges VT, Silva MG. Detection of Streptococcus agalactiae colonization in pregnant women by using combined swab cultures: cross-sectional prevalence study. São Paulo Med J. 2010;128:60–62. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802010000200003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verani JR, McGee L, Schrag SJ. Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease - revised guidelines from CDC, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kruk CR, Feuerschuetteb OH, Silveira SK, Cordazo M, Trapani A., Júnior Epidemiologic profile of Streptococcus agalactiae colonization in pregnant women attending prenatal care in a city of southern of Brazil. Braz J Infect Dis. 2013;17:722–723. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitima KT, Ntamako S, Birindwa AM, Mukanire N, Kivukuto JM, Tsongo K, et al. Prevalence of colonization by Streptococcus agalactiae among pregnant women in Bukavu, Democratic Republic of the Congo. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2014;8:1195–1200. doi: 10.3855/jidc.5030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]