Abstract

Hippocampal functioning contributes to our ability to generate multifaceted, imagistic event representations. Patients with hippocampal damage produce event narratives that contain fewer details and fewer imagistic features. We hypothesized that impoverished memory representations would influence language at the word level, yielding words lower in imageability and concreteness. We tested this by examining language produced by patients with bilateral hippocampal damage and severe declarative memory impairment, and brain-damaged and healthy comparison groups. Participants described events from the real past, imagined past, imagined present, and imagined future. We analyzed the imageability and concreteness of words used. Patients with amnesia used words that were less imageable than those of comparison groups across time periods, even when accounting for the amount of episodic detail in narratives. Moreover, all participants used words that were relatively more imageable when discussing real past events than other time periods. Taken together, these findings suggest that the memory that we have for an event affects how we talk about that event, and this extends all the way to the individual words that we use.

Keywords: Declarative memory, Word use, Language production, Hippocampal amnesia

1. Introduction

When we look back at the events and experiences of our daily lives, we can generate a vivid imagistic representation of specific events, with rich detail and multisensory features that produce the feeling of re-experiencing the event. The relational binding of the perceptual, sensory, temporal, and spatial components of events reflects the flexible (re)construction and (re)instantiation of declarative (episodic) memories; this phenomenon has been linked to the hippocampus and other medial temporal lobe structures (MTL) (e.g., Eichenbaum and Cohen, 2001). The hippocampus and MTL have also been implicated in integration and retrieval of the perceptual details that constitute rich, vivid episodic memories across (e.g., Schacter and Addis, 2009; St-Laurent et al., 2014). Patients with hippocampal amnesia produce autobiographical narratives of past and future events that contain significantly fewer episodic details and that are described and rated as less vivid than those of healthy comparison participants (e.g., Hassabis et al., 2007; Kurczek et al., 2015; Race et al., 2011).

The hippocampus and hippocampal-dependent declarative memory have also been implicated in language use and processing. Hippocampal amnesic patients have a range of sentence and discourse level deficits in both production and in comprehension (e.g., Duff and Brown-Schmidt, 2012; 2017; MacKay et al., 1998), even extending to nonverbal aspects of language: amnesic patients gesture less than healthy comparison participants during narrative production (Hilverman et al., 2016). Hippocampal functioning has also been linked to semantic processing and knowledge. Hippocampal theta oscillations are modulated by the amount of linguistic context in a sentence, suggesting a role for the hippocampus in relating incoming words to stored semantic knowledge during sentence comprehension (Piai et al., 2016). Furthermore, hippocampal amnesic patients perform significantly worse than comparison participants on measures of semantic richness and vocabulary depth for previously acquired, highly familiar words (Klooster and Duff, 2015). In a case of developmental amnesia, abnormal extrinsic feature knowledge for object concepts and typicality judgments for nonliving concepts have been reported (Blumenthal et al., 2017). Despite these demonstrations of hippocampal involvement in language processing, it is unknown if these disruptions following hippocampal damage and declarative memory impairment extend to the individual words used to describe representations in memory. Exploratory analyses conducted on a previously published data set suggested that this was the case (Hilverman et al., 2016). Accordingly, we tested this hypothesis by examining the imageability and concreteness of words used in a narrative task by amnesic patients and comparison participants.

There are reasons to expect that the hippocampus and hippocampal-dependent declarative memory affect the words used when describing events. Features of words reflect characteristics of what the word describes. For example, a word’s imageabilty measures the degree to which the word invokes an image in one’s mind. A word’s concreteness measures the degree to which the word can be seen or felt. These properties are known to affect memory for words; words higher in imageability and concreteness (e.g., house, book) are typically easier to remember than words lower in imageability and concreteness (e.g., truth, democracy) (Begg and Paivio, 1969; Paivio et al., 1994). But less is known about the reverse relationship: how does the vividness and integrity of the memory representation being described affect the words used to describe it? One possibility is that the vividness and detail of declarative memory representations in turn affect the imageabilty and concreteness of the specific words used to describe those same memories.

A link between memory and word use is evident in the language use of people with dementia and with Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). Studies comparing the language production of people with dementia to healthy older adults have found a reduction in word specify for people with dementia, with increased use of indefinite nouns and low imageability verbs (Bird et al., 2000; Maxim and Bryan, 1994). A similar pattern is found in AD; a comparison of the language production of Ronald Reagan – later diagnosed with AD – and George H.W. Bush – aging normally – uncovered that Reagan used words lower in imageabilty and used more indefinite nouns (e.g., anything, someone; Berisha et al., 2015). Patients with AD and individuals with hippocampal amnesia have similarities in their memory impairment and in MTL pathology. If the ability to generate rich imagistic and multisensory mental representations – supported by the hippocampus – influences word use, then, like patients with AD, patients with hippocampal amnesia should have impairments in word use as a result of their memory impairment. Here we examine if the hippocampus – via declarative memory - supports the production of highly imageable words.

Patients with amnesia are known to produce narratives that contain fewer details (Kurczek et al., 2013; Race et al., 2011). However, the specific words that are used are not necessarily related to the number of episodic details. Similar representations can be communicated with the same amount of episodic details using words that vary considerably in their imageability and concreteness. For example, one could say, “I was on a jetski on a nice summer day and water was hitting my face as I went across the lake” or “I was riding a jetski on a bright summer day and water was spraying my face as I sped across the lake”. In both cases, the number of details is the same, but the imageability and concreteness of the words used are much greater in the second version.

If the integrity of hippocampally-generated representations is responsible, in part, for the use of imagistic lexical items, then amnesic patients would be expected to use words that are less imageable and concrete than comparison participants, even when their narratives contain the same number of details. Moreover, we might expect that participants will use words that are more imageable when describing a past event that they actually experienced compared with an imagined event. Alternatively, memory representations may only affect discourse-level features of narratives like the number of episodic features, with little effect on the specific words that are used to communicate these narratives. We investigated this by analyzing properties of the words produced by patients with hippocampal amnesia and healthy comparison participants as they constructed narratives.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were six (one female) individuals with bilateral hippocampal damage, five (two female) brain-damaged comparison individuals with bilateral vmPFC damage and no memory impairment, and eleven (three female) healthy, demographically-matched comparison individuals (NC). These participants were recruited from the Patient Registry of the University of Iowa’s Division of Behavioral Neurology and Cognitive Neuroscience and were characterized neuropsychologically and neuroanatomically according to established protocols (Tranel, 2009). The Institutional Review Board at the University of Iowa approved all procedures for Human Subjects Research.

At the time of data collection, the participants with hippocampal damage (HC) were in the chronic epoch of amnesia, with time-post-onset ranging from 8 to 28 years (see Table 1). Hippocampal patients were, on average, 53.2 years old (range 45–61 years), and had, on average, 15 years of education (range 12–16 years). Etiologies included anoxia/hypoxia (n = 4) resulting in bilateral hippocampal damage, as well as herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE; n = 2), resulting in extensive bilateral medial temporal lobe damage affecting the hippocampus, amygdala, and surrounding cortices (see Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Demographic, neuroanatomical, and neuropsychological characteristics of participants with hippocampal (AM) and vmPFC (BDC) damage.

| Group | Subject | Sex | Age | Hand | Ed | Etiology | WAIS III FSIQ | WMS III GMI | BNT | TT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM | 1606 | M | 61 | R | 12 | Anoxia | 91 | 66 | 32 | 44 |

| 1846 | F | 46 | R | 14 | Anoxia | 84 | 57 | 43 | 41 | |

| 1951 | M | 61 | R | 16 | HSE | 106 | 57 | 49 | 44 | |

| 2308 | M | 53 | L | 16 | HSE | 98 | 45 | 52 | 44 | |

| 2363 | M | 53 | R | 18 | Anoxia | 98 | 73 | 58 | 44 | |

| 2563 | M | 54 | L | 16 | Anoxia | 102 | 75 | 52 | 44 | |

| Mean | 54.6** | 15.3 | 96.5 | 62.1 | 47.7 | 43.5 | ||||

| BDC | 318 | M | 73 | R | 14 | Meningioma Resection | 143 | 109 | 60 | 44 |

| 2352 | F | 64 | R | 14 | SaH; ACoA | 106 | 109 | 54 | 44 | |

| 2391 | F | 67 | R | 12 | Meningioma Resection | 109 | 132 | 57 | 43 | |

| 2577 | M | 73 | R | 11 | SaH; ACoA | 84 | 96 | 55 | 44 | |

| 3350 | M | 61 | R | 18 | Meningioma Resection | 118 | 108 | 52 | N/A | |

| Mean | 67.6** | 13.8 | 109.4 | 102.7 | 54.2 | 43.7 |

Note: M = Male; F = Female; R = Right-handed; Ed = years of education; WAIS-III FSIQ = Weschler Adult Intelligence Scale-III Full Scale Intelligence Quotient; WMS-III GMI = Weschler Memory Scale-III General Memory Index; BNT = Boston Naming Test; TT = Token Test.

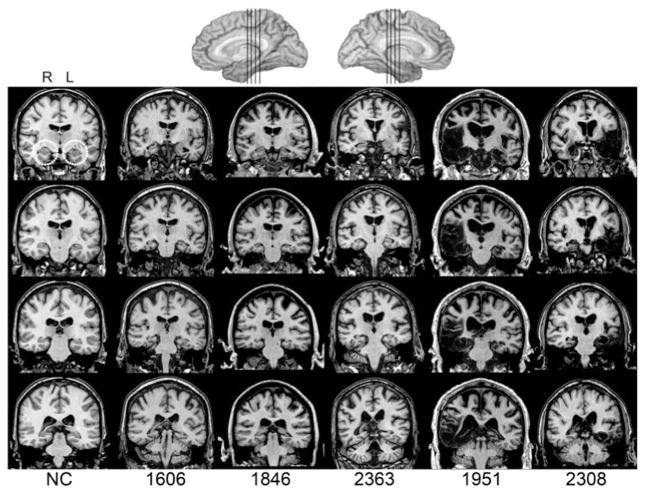

Fig. 1.

Magnetic resonance scans of hippocampal patients. Images are coronal slices through four points along the hippocampus from T1-weighed scans. Volume changes can be noted in the region of the hippocampus bilaterally for patients 1606, 1846, and 2363 and significant bilateral damage to the MTL, including hippocampus, can be observed for 1951 and 2308. R = right; L = left; NC = a healthy comparison brain.

The brain-damaged comparison (BDC) participants had an average chronicity of 18.4 years (range 10–38 years; Table 1). They were, on average, 67.6 years old (range 61–73 years), which was significantly older than the patients with amnesia (t(9) = 3.85, p = 0.003); for this reason, we included two healthy comparison groups, with a demographically matched healthy comparison for each patient. The BDC participants had, on average, 14 years of education, which did not significantly differ from that of the patients with amnesia (t(9) = 1.07, p = 0.31). On the neuropsychological battery, the HC participants did not differ significantly from the BDC participants on measures of intelligence (FSIQ (t(9) = 1.67, p = 0.13)) or language comprehension (Token Test (t(9) = 0.72, p = 0.49)) or language production/naming (Boston Naming Test (t(9) = 1.85, p = 0.1)). The only significant difference between patient groups, besides age, was their performance on the Weschler Memory Scale; consistent with bilateral hippocampal damage and amnesia, the HC group performed significantly worse (t(9) = −6.61, p < 0.001).

Eleven healthy comparison participants were matched pairwise on sex, age, and education separately to the each of the participants with amnesia and BDC groups (NC_AM; n = 6; age – mean = 54.3; SD = 5.8; p = 0.29; education – mean = 16.2; SD = 1.6; p = 0.43) and vmPFC (NC_BDC; n = 5; age – mean = 69.8; SD = 4.7; p = 0.51; education – mean = 6.8 l; SD = 2.6; p = 0.11) group.

2.2. Procedures

The current study is a reanalysis of data reported by Kurczek et al. (2015). In that study, participants were given a neutral cue word (bird, clock, farm, garden, hotel, lake, radio, restaurant, river, snow, teacher, truck) and asked to produce 12 narratives, including three unique narratives of autobiographical events occurring in each of four time periods (Real Past, Imagined Past, Imagined Present, and Future). The cue words were chosen so that they did not vary systematically on measures of valence (p = 0.21), arousal (p = 0.26), frequency (p = 0.43), or imaginability (p = 0.53). Instructions were given orally to participants and written instructions in bullet point format were also provided and were available within view of participants, reducing memory demands of the task. Participants were told that their Real Past narratives needed to be autobiographical events that had happened to them personally, rather than something that happened to someone else. For Imagined Past, Imagined Present and Future events, participants were asked to construct events that had not happened to them before. Participants were instructed to choose Real Past events that had happened only once and that had occurred before they were 25 years old. They were asked to construct Imagined Past events that met these criteria as well. For Future events, there was no limit for how far into the future the event could be set. These constraints encouraged participants to draw disproportionately from their episodic memory for which they had specific (but infrequent) autobiographical experiences.

Once participants had selected an event that fit the criteria, participants were asked to provide a title, time, and location for the event. Participants then were asked to provide a one- to two-minute overview of what happened or might have happened during the event (i.e., the event that lasted a few minutes to a few hours). Participants were subsequently asked to select a specific moment from the event they described and were prompted to produce a narrative of the setting and experience of that specific moment. They were given 90 s to do so. Participants were encouraged to use the full-allotted time. If a participant indicated they could not think of anything else, the experimenter encouraged the participant to keep thinking and would remind the participant of the instructions. We restricted analyses to these 90 s descriptions of a specific moment of the (re)constructed event. In the original analysis of these data, Kurczek et al. (2015) found that the patients with hippocampal amnesia produced narratives that contained significantly fewer episodic details, across all time periods, consistent with the literature (Race et al., 2011). Sessions were video- and audio-taped for analysis.

2.3. Coding

Explanations were transcribed and all spoken words were coded as either function words or content words. Function words included prepositions (e.g., in, under), pronouns (e.g., she, me), auxiliary verbs (e.g., do, have), articles (e.g., the, an), and particles (e.g., well, um).

To examine the lexical properties of the words produced, we used the MRC Psycholinguistic database, a Machine Useable Dictionary that provides linguistic properties for 150,937 words. For each content word in our dataset, we extracted imageability, concreteness, and Brown verbal frequency. The scales for imageability and concretenesss were derived by merging three sets of norms: an extension of Paivio et al. (1968), Toglia and Battig (1978) and Gilhooly and Logie (1980). Brown verbal frequency provides a frequency count of more than 190,000 words of spoken English, based on a published corpus of spontaneous conversation (Brown, 1984). For more information about these measures, see the MRC Psycholinguistic database website (http://websites.psychology.uwa.edu.au/school/MRCDatabase/uwa_mrc.htm).

To assess a potential relation between lexical properties of individual words and the number of episodic detail in the narratives we used the previously reported (Kurczek et al., 2015) coding of episodic and semantic content following the Autobiographical Interview (AI) scoring procedures outlined by Levine et al. (2002). Consistent with established conventions, details were defined as unique occurrences, observations or thoughts, which each independently convey information, and each detail was classified as either internal or external. Internal details pertained directly to the prompted task/main event described and contained elements of episodic reconstruction and re-experiencing (e.g., reference to event, time, place, perceptual and emotional/though information). External details were those considered to be extraneous to the main event as well as semantic and other details and repetitions. The main variable of interest was the proportion of internal-to-total details per narrative, a measure of episodic re- experiencing. We have previously reported that these same patients with hippocampal amnesia produce significantly fewer episodic details in their autobiographical narratives than comparison groups (Kurczek et al., 2015).

2.4. Experimental design and statistical analyses

We analyzed the distribution of word types produced using mixed effects regression models to account for the random variance in the data associated with participant and components of the design not directly related to our questions, increasing statistical power. For example, because hundreds of observations (words) were produced by each participant, including a random intercept for participant accounts for the imageability of the words produced by a particular individual while still allowing for a general pattern that is associated with a particular participant group. Each model predicted the feature of interest, standardized for normality, as a function of group (amnesic, BDC, NC). We assessed the effect of time period in the models by including it as a fixed effect (real past, imagined past, imagined present, imagined future) and also including the interaction of time period and group. Group and time period were effect coded, such that each effect was calculated with respect to the grand mean of all participants; this increased potential power to detect interactions with time period while also ensuring that main effects can be interpreted across time periods. Random effect structure was determined by using model comparison to find the maximal random effect structure supported by the data. All models included random intercepts for the patient-comparison pair, and a random slope for time period was included in the models in which a likelihood ratio test comparing models with and without the slope was significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Word count

On average, healthy comparison participants produced 195.75 (sd = 61.87) words, BDCs produced 168.78 (sd = 72.31) words, and patients with amnesia produced 152.11 (sd = 76.48) words for each narrative. A mixed effect model was used to predict word count, log-transformed and standardized, and including a random slope for time period on a random intercept for participant. Patients with amnesia produced fewer words in their narratives relative to the grand mean (β = −0.52, t(22.1) = −3.47, p = 0.002). Brain-damaged comparisons produced a number of words that did not, on average, differ from the grand mean (β = −0.03, t(14.1) = 0.11; p = 0.91). There was also one main effect of time period that was significant; all participants produced more words when talking about Real Past events compared to the grand mean (β = 0.27, t(121.3) = 3.23, p = 0.002). This effect was not present for Imagined Past events (β = −0.08, t(63.1) = −0.89; p = 0.38) nor Imagined Present events (β = 0.03, t(39.2) = 0.30, p = 0.76). The patients with amnesia group did not significantly interact with time period (PE: β = 0.13, t(219.3) = 1.07, p = 0.28; IPastE: β = 0.12, t(199.8) = 1.037, p = 0.30; IPresentE: β = 0.13, t(171.2) = 1.10, p = 0.27). The brain-damaged comparisons group also did not interact with time period PE: (β = 0.03, t(131.3) = 0.28, p = 0.77; IPastE: β = −0.17, t(71.5) = −1.34, p = 0.18; IPresentE: β = −0.04, t(45.4) = −0.33, p = 0.74).

3.2. Word type

Prior analyses of features of words used have focused exclusively on content words – words that carry meaning (e.g., run, dog) – rather than function words – words that serve a grammatical purpose but lack meaning on their own (e.g., the, to). Function words tend to be high in frequency and low in imageabilty. To assess whether function word use was comparable across groups, we calculated the rate of function word use, the number of function words used divided by the total number of words. Healthy participants used function words for 41.2% of all words, BDCs 40.7% of all words, and patients with amnesia 43.5% of all words. A mixed effect model predicting the logit-transformed percentage of function words, and including a random slope for time period, revealed that patients with amnesia used function words at a higher rate relative to the grand mean (β = 0.53, t(66) = 3.39, p < 0.002). Additionally, brain-damaged comparison participants used function words at a lower rate relative to the grand mean (β = −0.33, t(66) = −2.02, p = 0.05). In order to ensure that this difference in rate of function word use did not influence findings, we restricted our later analyses to only content words.

None of the time periods predicted rate of function word use (PE: β = −0.09, t(24) = −0.53, p = 0.60; IPastE: β = −0.09, t(16) = −0.53, p = 0.60; IPresentE: β = −0.07, t(37) = −0.42, p = 0.68). For the interaction of group and time period, there was a marginal interaction for the patients with amnesia; these patients used fewer function words when describing past events relative to the grand mean (β = −0.38, t(58) = −1.68, p < 0.1). The remaining interactions of the patients with amnesia group and time period were not significant (IPastE: β = 0.08, t(54) = 0.37, p = 0.72; IPresentE: β = −0.13, t(57) = −0.58, p = 0.56). The brain-damaged comparison group did not significantly interact with any of the time periods (PE: β = 0.09, t(58) = 0.39, p = 0.72; IPastE: β = 0.02, t(53) = 0.08, p = 0.92; IPresentE: β = 0.16, t(57) = 0.68, p = 0.50).

3.3. Unique words

We next assessed the number of unique content words that were used by each participant group to assess whether any effects of imageabilty or concreteness might be due to differences in the number of unique words. Patients with amnesia on average produced 98.48 (sd = 27.57) unique words, brain-damaged comparisons produced 97.08 (sd = 28.32) words, and healthy comparisons produced 110.86 (sd = 27.11) words. We analyzed these data with a model that predicted the number of unique words, standardized, as a function of group, time period, and their interaction, along with a random intercept for participant pair with a random slope on the intercept for time period. The main effects of group were not significant for patients with amnesia (β = −0.12, t(19) = −0.47, p = 0.64) nor brain-damaged comparisons (β = −0.19, t(19) = −0.70, p = 0.49). There was a significant main effect of time period for the Real Past Events (β = 0.20, t(23) = 2.32, p = 0.03); participants used more unique words when discussing Real Past events relative to the grand mean. This was not significant for Imagined Past Events (β = 0.13, t(44 = −1.51, p = 0.13) nor Imagined Present Events (β = −0.05, t(53) = −0.65, p = 0.52). None of the interactions of group and time period were significant for the patients with amnesia (PE: β = 0.17, t(24) = 0.37, p = 0.20; IPastE: β = 0.004, t(47) = 0.04, p = 0.97; IPresentE: β = 0.02, t(55) = 0.19, p = 0.85). Similarly, none of the interactions of group and time period were significant for the brain-damaged comparisons (PE: β = 0.03, t(23) = 0.23), p = 0.82); IPastE: β = −0.02, t(43) = −0.67, p = 0.51; IPresentE: β = −0.12, t(52) = −1.01, p = 0.31).

3.4. Imageability

Imageability was log-transformed for normality and standardized. A mixed effect model was used to predict imageability, including a random intercept and slope for time period for matched participant pair. Three covariates were included in this analysis. First, word count, log-transformed and standardized, was included in the model to account for differences in length of the narratives. Second, verbal frequency, log-transformed and standardized, was included in the model. Because word frequency and imageability are highly correlated (r > 0.8), this covariate ensured that any effects that we uncovered were above and beyond simple frequency effects. Third, proportion of episodic features from Kurczek et al. (2015), standardized, was included in the model to account for differences in the number of episodic details contained in the narratives. Proportion of episodic detail did not predict imageability rating in any of the individual groups.1 See Fig. 2 for a scatterplot of the proportion of episodic details and the mean imageabilty of words used in a narrative.

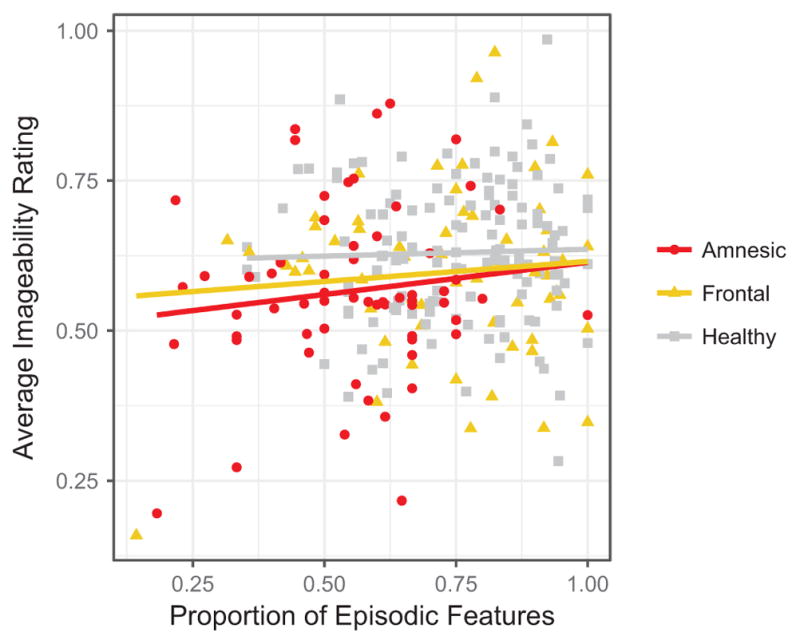

Fig. 2.

Proportion of episodic features – taken from Kurzcek et al. (2015) – and average imageability rating in each narrative by group. Proportion of episodic features did not significantly predict imageabilty.

As expected, log-transformed verbal frequency predicted imageability (β = −0.58, t(19417) = −86.94, p < 0.001); words high in frequency tended to be low in imageability. Log-transformed word count did not significantly predict imageability (β = 0.002, t(179) = 0.32, p = 0.75). The proportion of episodic features did not significantly predict imageability (B = 0.003, t(800) = 0.44, p = 0.66). Critically, there was a main effect of group; patients with amnesia used words that were significantly less imageable compared to the grand mean (β = −0.02, t(161) = −2.04, p < 0.05; Fig. 3). The effect of group on imageability was not significant for the BDC group (β = 0.01, t(123) = 1.17, p = 0.24). There was also a main effect of time period; participants tended to use words that were more imageable when describing Real Past events relative to the grand mean (β = 0.04, t(17) = 3.09, p = 0.007). This effect was not present for Imagined Past events (β = −0.008, t(129) = −0.75, p = 0.45) nor Imagined Present events (β = −0.01, t(229) = −0.71, p = 0.48). None of the interactions of group and time period were significant for the patients with amnesia (PE: β = 0.009, t(113) = 0.56, p = 0.58; IPastE: β = 0.02, t (1288) = 1.54, p = 0.12; IPresentE: β = −0.01, t(1522) = −0.69, p = 0.49). Similarly, none of the interactions of group and time period were significant for the brain-damaged comparisons (PE: β = −0.005, t(93) = −0.33), p = 0.74); IPastE: β = −0.02, t(699) = −1.75, p = 0.08); IPresentE: β = 0.01, t(1376) = 0.67, p = 0.50).

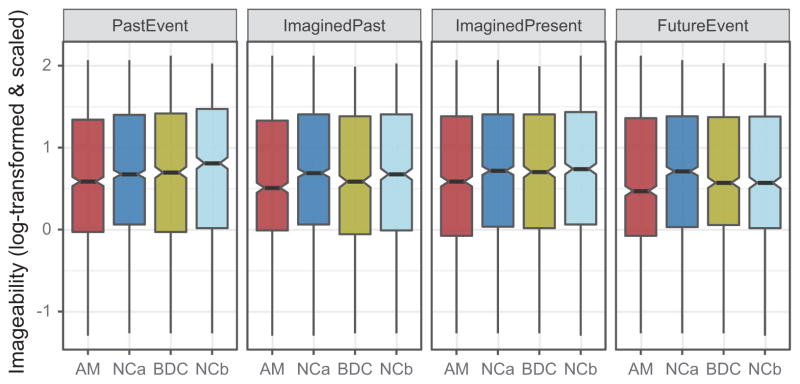

Fig. 3.

Boxplot of word imageability by group for all time periods. Across time periods, patients with amnesia produce words that are significantly less imageable than the grand mean. Past events also yield words that are significantly higher in imageability compared to the grand mean. The upper and lower hinges correspond to the first and third quartiles. (AM = amnesic participants; NCa = healthy comparison participants matched to amnesic participants; BDC = brain-damaged comparison participants; NCb = healthy comparison participants matched to brain-damaged participants.).

3.5. Concreteness

A model of the same structure was used to predict concreteness, log-transformed, with a random slope for time period on the intercept for matched participant pair. We again included covariates for word count and verbal frequency, both log-transformed and standardized, as well as the proportion of episodic features.2

As expected, log-transformed verbal frequency predicted concreteness (β = −0.59, t(17823) = −87.6, p < 0.001). Log-transformed word count did not significantly predict concreteness (β = 0.004, t (423) = 0.57, p = 0.57). The proportion of episodic features did predict concreteness (B = 0.02, t(922) = 2.38, p = 0.02); narratives with a higher proportion of episodic features contained words higher in concreteness. Group did not predict concreteness for patients with amnesia (B = −0.01, t(362) = 0.76, p = 0.45) nor brain-damaged comparison participants (B = 0.003, t(298) = 0.24, p = 0.81; Fig. 4). There were no main effects of time period for events in the real past (β = 0.02, t(26) = 1.66, p = 0.11), imagined past (β = 0.01, t(37) = 1.23, p = 0.23), or imagined present (β = −0.008, t(81) = −0.71, p = 0.48). None of the interactions of group and time period were significant for the patients with amnesia (PE: β = −0.005, t(122) = −0.30, p = 0.76; IPastE: β = 0.01, t(912) = 0.66, p = 0.51; IPresentE: β = 0.004, t(1697) = 0.30, p = 0.77). Similarly, none of the interactions of group and time period were significant for the brain-damaged comparisons (PE: β = 0.01, t(99) = 0.89, p = 0.37; IPastE: β = −0.02, t(559) = −1.25, p = 0.21; IPresentE: β = 0.01, t(1293) = 0.39, p = 0.69).

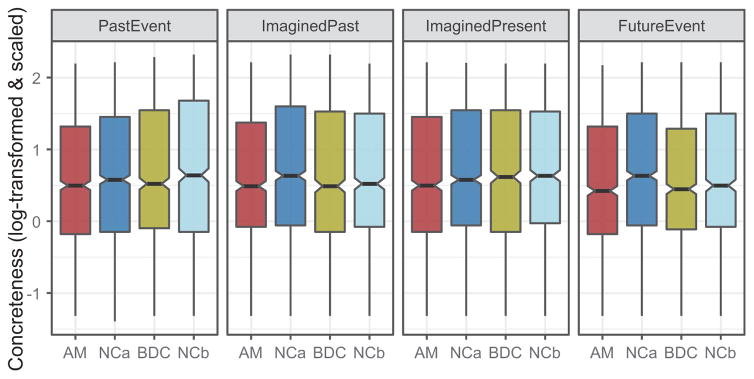

Fig. 4.

Boxplot of word concreteness by group for all time periods. Across time periods, patients with amnesia produce words that are not reliably different in concreteness from the grand mean. The upper and lower hinges correspond to the first and third quartiles (AM = amnesic participants; NCa = healthy comparison participants matched to amnesic participants; BDC = brain-damaged comparison participants; NCb = healthy comparison participants matched to brain-damaged participants.).

3.6. Imageability over time

Although our previous analyses accounted for the total number of words produced in each narrative, it is possible that imageability of words changes throughout the narrative (i.e., more imageable words are produced either earlier or later in the narratives). To ensure that any differences in imageability ratings were not due to specific groups using words that were more imageable earlier or later in the narratives we analyzed the imageability rating as a function of word number in each narrative. A model was used predicting imageability, log-transformed, with a fixed effect of word number, log-transformed, group, and their interaction. There was a random intercept for time period and a random intercept for participant pair. Word number did not significantly predict imageability (B = −0.003, t(36559) = −0.394, p = 0.69), nor did it interact with participant status for patients with amnesia (B = −0.004, t(41068) = −0.36, p = 0.71) or brain-damaged comparisons (B = −0.006, t(27870) = −0.56, p = 0.58). Group did not predict imageability for patients with amnesia (B = −0.042, t(36237) = −0.78, p = 0.43) nor did it for the BDC group (B = 0.023, t(29871) = 0.43, p = 0.67).

4. Discussion

We tested the hypothesis that the integrity of hippocampal declarative memory representations affects the imageabilty and concreteness of the individual words used to describe events in memory during narrative tasks. We found that patients with amnesia produced words that were less imageable than healthy and brain-damaged comparison groups, even when accounting for word frequency, the amount of language produced, and the amount of episodic detail in the narrative. This pattern was not reliable for concreteness. These findings suggest a potential mechanism for changes in word use with cognitive decline associated with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, specifically that this pattern may be directly related to the functioning of the hippocampal dependent declarative memory.

It is important to distinguish the potentially distinct contributions of the hippocampus and of declarative memory to the findings reported here, and to the lexical properties of individual words and their use more broadly. The hippocampus, and its hallmark processing features of relational binding and representational flexibility, have long been linked to the formation and subsequent retrieval of highly detailed declarative (episodic) memory (Eichenbaum and Cohen, 2001). Hippocampal activation has been linked to the retrieval of highly detailed and vivid episodic (past and future) memories, and hippocampal damage has been shown to significantly reduce the number of perceptual details in narratives of episodic events (e.g., Addis et al., 2004; Hassabis et al., 2007; Kurczek et al., 2015; Race et al., 2011; Schacter and Addis, 2009; St-Laurent et al., 2014). We, and others, have also pointed to a multitude of ways that these same processing features of the hippocampus make direct contributions to language use and processing. The data from the current study provide support for a direct relationship between declarative memory – and its associated perceptual features –and word use. When declarative (episodic) memory representations are impoverished – or less vividly imageable – the words used to convey those mental representations in language are also impoverished – or less vividly imageable.

The most compelling evidence for this interpretation is the difference in imageability of words used to describe real past events versus imagined events; words were more imageable for real past events across all participant groups. Although patients with amnesia were less likely to use highly imageable words overall, like comparison participants, they produced more imageable words, than average, for the real past events. This suggests that the perceptual quality of the declarative memory representation of real past events – the only type of narrative that participants have actually experienced – differed, and this was evident in words used to describe those events. If, however, the hippocampus was making direct contributions to word retrieval and use independently of its mediating role in declarative memory, we might expect less imageable word use to be a static characteristic of the language of patients with amnesia rather than one modulated by the nature of the declarative memory representation. Thus, these data speak to the influence of declarative memory on lexical retrieval. Hippocampal processes, as constrained by the current design and analyses, seem to affect the integrity and vividness of the event representation being discussed, and in turn, these representations were described using less imageable words. Future studies that examine other types of language production are warranted to further test this interpretation. For example, researchers have argued that discourse tasks such as picture description may place fewer demands on declarative memory than autobiographical narrative tasks (Race et al., 2011).

That said, these data do not rule out the possibility that the hippocampus may play a direct or functional role in individual word use and retrieval as well. For example, Klooster and Duff (2015) reported that many of the same patients with amnesia studied here perform significantly worse on measures of vocabulary depth and semantic richness than healthy comparison participants, even for highly familiar words acquired long before the onset of their amnesia. The interpretation of this finding was that the hippocampus may strengthen the representations of individual words and their relations to other, semantically related, words. Such an interpretation leaves open the possibility of a more direct route between hippocampal processing and word use. Furthermore, a role for the hippocampus has been articulated in relating incoming words to each other and to stored semantic knowledge during sentence comprehension in order to build meaning across words (Piai et al., 2016). However, Piai et al. (2016) suggest that the hippocampus, as measured by theta power increases during sentence processing, likely does not make direct contributions to lexical retrieval in their task given the lack of a relationship between theta power and picture naming latencies. While direct evidence for a role of the hippocampus in lexical retrieval awaits further study, the findings reported here – that patients with hippocampal damage and declarative memory impairment produce words that are less imageable than healthy and brain-damaged comparison participants – raise interesting questions regarding the complex and potentially interdependent relationship between the hippocampus, declarative memory, and the lexical properties of individuals words and their use during language production.

The link between the hippocampus and declarative memory is well-established, as is the link between declarative memory and episodic features. Here, we found that, even when accounting for number of episodic details in the narratives, the imageabilty of the words used in these narratives was lower in patients with amnesia relative to that of the comparison groups. These findings suggest that the number of episodic details and the lexical properties of individuals word, while both related to declarative memory representations, may differ in their sensitivity in measuring episodic re-experiencing. For example, examination of the episodic details contained in narratives across time periods has not previously distinguished real and imagined events (e.g,. Kurczek et al., 2015; Race et al., 2011). Our findings suggest that imageability of the specific words used may provide a more sensitive index of the degree of episodic re-experiencing, or integrity of the underlying mental representation, than the number of episodic details. The imageability of specific words used in narrative production may also influence subjective ratings of narrative richness and episodic re-experiencing independently of the number of episodic details. These speculations warrant further investigation. In the meantime, these data provide initial evidence that the nature of the declarative memory representation being described affects the words used to describe it, above and beyond the number of episodic details present in the narrative.

These findings extend the scope of observed disruption in language use in patients with hippocampal amnesia. Previous work has reported a range of sentence and discourse deficits in language use and processing in patients with hippocampal amnesia across production and comprehension tasks (e.g., Brown-Schmidt and Duff, 2016; Duff and Brown-Schmidt, 2012; 2017; MacKay et al., 1998; see also Piai et al., 2016). The novel findings here – that patients with amnesia use words that are less imageable in their verbal narratives of past and imagined events with relatively more imageable words for real, past events –highlight the potential difference in accounting for direct hippocampal contributions to language and hippocampal contributions to language through its mediating role in support of declarative memory. For example, there are a number of other works that specifically implicate hippocampal declarative memory in contributing to language use. Patients with amnesia gesture at lower rates when describing past events (Hilverman et al., 2016) and are impaired at producing definite reference (e.g., the angle vs. an angle) to explicitly signal that something is mutually known (Duff et al., 2011). These are examples where disruptions in language use are most parsimoniously interpreted as resulting from impoverished declarative memory representations.

Other studies on hippocampal contributions to language suggest a more direct link between the processing features of the hippocampus (e.g., relational binding, representational compositionality and flexibility) and aspects of language use and processing. For example, when binding the temporal, order-of-mention information to the first- and second-mentioned characters in order to disambiguate a pronoun (e.g., Melissa and Debbie attended the conference. She…), healthy listeners show a strong preference for interpreting the pronoun as the first mentioned character, while patients with hippocampal amnesia, who are impaired at binding the temporal order of the constituent elements of an event, do not show this preference (Kurczek et al., 2013). The work by Piai et al. (2016) is another example of direct hippocampal contributions to language processing. That said, it is difficult to parse and rule out the influence declarative (episodic) memory may play in a given task. While future work that attempts to control for such influence and distinct contribution is warranted, the data here are consistent with the broader literature pointing to a role for the hippocampus in language, either contributing directly or through its mediating role in support of declarative memory.

These findings provide strong support for a functional role of hippocampal dependent declarative memory in language production. Despite the lack of aphasia or semantic dementia – and the traditional view of amnesia as an impairment specific to the domain of memory, leaving language intact– examining more nuanced properties of language use in individuals with amnesia suggests a pattern of disruption. Understanding these disruptions will inform our understanding of how memory representations contribute to and support language across contexts and levels. The memory that we have for an event affects how we talk about that event, and this extends all the way to the words that we use.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [NIDCD R01-DC011755] and an NSF-GRF awarded to CH. We thank Joel Bruss for making the anatomical figure and Jake Kurczek for providing the data from Kurczek et al. (2015).

Footnotes

We analyzed this with models predicting mean imageabilty as a function of proportion of episodic features with a random intercept for participant for each group separately. This was not significant for the amnesic group (B = −0.05, t(57) = −0.54, p = 0.6), BDC group (B = 0.07, t(58) = 0.77, p = 0.4), or healthy group (B = 0.05, t(130) = 0.67, p = 0.5).

We analyzed this with models predicting mean concreteness as a function of proportion of episodic features with a random intercept for participant for each group separately. This was not significant for the amnesic group (B = 0.02, t(57) = 0.28, p = 0.78) or healthy group (B = 0.05, t(129) = 0.64, p = 0.5). Proportion of episodic details marginally predicted concreteness for the BDC group (BDC group (B = 0.16, t(58) = 1.76 p = 0.08).

References

- Addis D, Moscovitch M, Crawley A, McAndrews M. Recollective qualities modulate hippocampal activation during autobiographical memory retrieval. Hippocampus. 2004;14(6):752–762. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg I, Paivio A. Concreteness and imagery in sentence meaning. J Verbal Learn Verbal Behav. 1969;8:821–827. [Google Scholar]

- Berisha V, Wang S, Lacross A, Liss J. Tracking discourse complexity preceding Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis: a case study comparing the press conferences of presidents Ronald Reagan and George Herbert Walker Bush. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;45:959–963. doi: 10.3233/JAD-142763. http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-142763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird H, Lambon Ralph Ma, Patterson K, Hodges JR. The rise and fall of frequency and imageability: noun and verb production in semantic dementia. Brain Lang. 2000;73(1):17–49. doi: 10.1006/brln.2000.2293. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/brln.2000.2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal A, Duke D, Bowles B, Rosenbaum RS, Köhler S. Abnormal semantic knowledge in a case of developmental amnesia. Neuropsychologia. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.06.018. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brown-Schmidt S, Duff M. Memory and common ground processes in language use. Top Cognit Sci. 2016;8:722–736. doi: 10.1111/tops.12224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff MC, Brown-Schmidt S. The hippocampus and the flexible use and processing of language. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6:69. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00069. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2012.00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff MC, Brown-Schmidt S. The Hippocampus from Cells to Systems. Springer International Publishing; 2017. Hippocampal Contributions to Language Use and Processing; pp. 503–536. [Google Scholar]

- Duff MC, Gupta R, Hengst Ja, Tranel D, Cohen NJ. The use of definite references signals declarative memory: evidence from patients with hippocampal amnesia. Psychol Sci. 2011;22(5):666–673. doi: 10.1177/0956797611404897. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0956797611404897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H, Cohen NJ. From Conditioning to Conscious Recollection: Memory Systems of the Brain. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gilhooly KJ, Logie RH. Age-of-acquisition, imagery, concreteness, familiarity, and ambiguity measures for 1944 words. Behav Res Methods Instrum. 1980;12:395–427. [Google Scholar]

- Hassabis D, Kumaran D, Vann SD, Maguire Ea. Patients with hippocampal amnesia cannot imagine new experiences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:1726–1731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610561104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0610561104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilverman C, Cook S, Duff MC. Hippocampal declarative memory supports gesture production: evidence from amnesia. Cortex. 2016;85:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2016.09.015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2016.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klooster NB, Duff MC. Remote semantic memory is impoverished in hippocampal amnesia. Neuropsychologia. 2015;79:42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.10.017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurczek J, Brown-Schmidt S, Duff M. Hippocampal contributions to language: Evidence of referential processing deficits in amnesia. J Exp Psychol: Gen. 2013;142(4):1346–1354. doi: 10.1037/a0034026. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0034026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurczek J, Wechsler E, Ahuja S, Jensen U, Cohen NJ, Tranel D, Duff M. Differential contributions of hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex to self-projection and self-referential processing. Neuropsychologia. 2015;73:116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.05.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B, Svoboda E, Hay JF, Winocur G, Moscovitch M. Aging and autobiographical. Mem: Dissociating Epis Semant Retr. 2002;17(4):677–689. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037//0882-7974.17.4.677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKay DG, Stewart R, Burke DM. H.M. revisited: relations between language comprehension, memory, and the hippocampal system. J Cognit Neurosci. 1998;10(3):377–394. doi: 10.1162/089892998562807. http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/089892998562807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxim J, Bryan K. Language of the elderly: A clinical perspective. Whurr Pub Ltd; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Paivio A, Walsh M, Bons T. Concreteness effects on memory: when and why? J Exp Psychol: Learn Mem Cognit. 1994;20(5):1196–1204. [Google Scholar]

- Paivio A, Yuille JC, Madigan SA. Concreteness, imagery, and meaningfulness values for 925 nouns. J Exp Psychol. 1968 doi: 10.1037/h0025327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piai V, Anderson KL, Lin JJ, Dewar C, Parvizi J, Dronkers NF. Direct Brain Recordings Reveal Hippocampal Rhythm Underpinnings of Language Processing. 2016 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603312113. < http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1603312113>. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Race E, Keane MM, Verfaellie M. Medial temporal lobe damage causes deficits in episodic memory and episodic future thinking not attributable to deficits in narrative construction. J Neurosci: Off J Soc Neurosci. 2011;31(28):10262–10269. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1145-11.2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1145-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacter DL, Addis DR. On the nature of medial temporal lobe contributions to the constructive simulation of future events. Philos Trans R Soc B. 2009;364:1245–1253. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0308. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2008.0308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Laurent M, Moscovitch M, Jadd R, Mcandrews MP. The perceptual richness of complex memory episodes is compromised by medial temporal lobe damage. Hippocampus. 2014;24:560–576. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22249. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hipo.22249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toglia MP, Battig WF. Handbook of semantic word norms. Lawrence Erlbaum; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Tranel D. The Iowa-Benton school of neuropsychological assessment. Neuropsychol Assess Neuropsychiatr Neuromedical Disord. 2009:66–83. [Google Scholar]