Abstract

The central complex comprises an elaborate system of modular neuropils which mediate spatial orientation and sensory-motor integration in insects such as the grasshopper and Drosophila. The neuroarchitecture of the largest of these modules, the fan-shaped body, is characterized by its stereotypic set of decussating fiber bundles. These are generated during development by axons from four homologous protocerebral lineages which enter the commissural system and subsequently decussate at stereotypic locations across the brain midline. Since the commissural organization prior to fan-shaped body formation has not been previously analysed in either species, it was not clear how the decussating bundles relate to individual lineages, or if the projection pattern is conserved across species. In this study, we trace the axonal projections from the homologous central complex lineages into the commissural system of the embryonic and larval brains of both the grasshopper and Drosophila. Projections into the primordial commissures of both species are found to be lineage-specific and allow putatively equivalent fascicles to be identified. Comparison of the projection pattern before and after the commencement of axon decussation in both species reveals that equivalent commissural fascicles are involved in generating the columnar neuroarchitecture of the fan-shaped body. Further, the tract-specific columns in both the grasshopper and Drosophila can be shown to contain axons from identical combinations of central complex lineages, suggesting that this columnar neuroarchitecture is also conserved.

Keywords: Insect, Development, Central complex, Commissural fascicles, Columnar neuroarchitecture

Introduction

The central complex comprises a modular system of neuropils and is a prominent feature of the central brain in all insects (see Strausfeld 2012). The various modules - protocerebral bridge (PB), fan-shaped body (FB; or upper division of the central body), ellipsoid body (EB; or lower division of the central body), noduli (N) and lateral accessory lobes (LAL) (see Strausfeld 2012; Ito et al. 2014; Wolff et al. 2015) - subserve a range of functions including spatial orientation and memory (Liu et al. 2006; Neuser et al. 2008; Pan et al. 2009), as well as sensory integration for motor control (Ilius et al. 1994; Strauss 2002; Heinze and Homberg 2007; Harley and Ritzmann 2010; Strausfeld and Hirth 2013).

The neuroarchitecture of the largest of these modules, the fan-shaped body, is characterized by layers of dendritic arbors and a stereotypic columnar organization stemming from clusters of neurons located in the pars intercerebralis region of each protocerebral hemisphere (Williams 1975; Homberg 1987; Heinze and Homberg 2008; el Jundi et al. 2010; Young and Armstrong 2010; Pfeiffer and Homberg 2014; Koniszewski et al. 2016). These cell clusters form part of four bilateral lineages called W, X, Y, Z in the grasshopper (Boyan and Williams 1997) and DPMm1/DM1, DPMpm1/DM2, DPMpm2/DM3, CM4/DM4 in Drosophila (Ito et al., 2013; Lovick et al., 2013; Wong et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2013; for simplicity sake, we will refer to the lineages as W, X, Y, Z for both species from here on onward). Based on the finding that their spatial arrangement and developmental characteristics are very similar in flies and locusts, the lineages are assumed to be homologous (Boyan et al., 2015). Developmental studies have revealed that the intricate columnar wiring of the fan-shaped body is established quite rapidly, but at stages which also vary with the lifestyle of the insect. In the grasshopper, it develops fully during embryogenesis (Boyan et al. 2008b, 2015), while in flies, it happens during pupal stages (Renn et al. 1999; Young and Armstrong 2010; Lovick et al., 2013; Riebli et al. 2013; Wolff et al. 2015; Lovick et al., 2017). The columnar neuroarchitecture itself is generated by a sophisticated mechanism of axogenesis known as “fascicle switching” in which a subset of W-Z axons of the embryonic grasshopper (Boyan et al. 2008b) and larval Drosophila (Young and Armstrong 2010; Riebli et al. 2013) brain decussates at stereotypic locations along the brain commissure, resulting in a discrete set of fiber bundles oriented orthogonally to the commissure. The decussating W-Z axons belong to the so-called columnar neurons which interconnect the modules of the central complex (i.e., protocerebral bridge, fan-shaped and ellipsoid bodies, noduli; see Heinze and Homberg 2008; Pfeiffer and Homberg 2014; Wolff et al. 2015). Comparative analyses suggest that the number of columns in a given species may relate to the number of lineages participating (see Strausfeld 2012) and that the mechanism is conserved throughout the Panarthropoda (Loesel et al. 2002; Boyan et al. 2015).

In previous studies, pioneer neurons from the W, X, Y, Z lineages of the grasshopper were shown to project into early embryonic commissural fascicles where they fasciculated with the pioneers of this commissural system (Williams and Boyan 2008). Since the embryonic commissural system itself was only grossly grouped into either anterior (ac) or posterior (pc) fascicles (Boyan et al. 2008b; Boyan and Williams 2011; Boyan et al. 2015) in keeping with the nomenclature applying to the adult ventral nerve cord (see Goodman and Doe 1994), the individual fascicles targeted by pioneers from the central complex lineages could not be specifically identified. Similarly in Drosophila, where axons from W-Z lineages have been shown to project into a primordial commissural system (Riebli et al. 2013), the dynamic topology of the decussating tracts during larval and pupal development has not been studied. It is therefore not clear whether the projections are organized according to lineage, and if so whether the pattern is conserved across species.

In this study, we took advantage of a database in which all the commissures of the adult grasshopper brain have been mapped (Boyan et al. 1993) in order to generate a nomenclature for the commissural fascicles present at mid-embryogenesis, prior to formation of the central complex. We then traced the axonal projections from lineages of the W, X, Y, Z system into the fascicles of this commissural system. Recent adavances in molecular labeling and imaging allow a parallel analysis to be performed in both the embryonic and larval brain of Drosophila. Our study reveals that the columnar neuroarchitecture of the fan-shaped body of both species involves equivalent columns which are generated by axons from homologous lineages projecting in a lineage-specific manner into a common commissural neuroarchitecture and decussating according to a conserved pattern of axogenesis.

Materials and methods

Animals

Grasshopper

S.gregaria eggs from our own culture were incubated in moist aerated containers at 30°C. Embryos were staged at time intervals equal to percentage of embryogenesis according to Bentley et al. (1979). Each data set is supported by repeated preparations. All experiments were performed strictly according to the guidelines for animal welfare as laid down by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

Drosophila

The Drosophila stocks utilized in this study include Oregon RT, R9D11-Gal4, 10xUAS-mCD8::GFP (Bloomington Stock Center, Bloomington, Indiana). Flies were grown at 25°C using standard fly media unless otherwise noted.

Immunolabeling

Grasshopper

Staged embryos were dissected out of the egg into ice-cold 0.1M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and freed from embryonic membranes. Brains were immersion fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C and subsequently washed for one hour in PBT (PBS plus 0.025% Triton X 100). Preparations were then embedded in 5% Agarose/PBS at 55–60°C, the solution allowed to cool, and the resulting block serially sectioned on a Vibratome (Leica VT 1000S) at 50μm thickness. Sections were collected in 0.1M PBS, freed from agarose, positioned onto Superfrost® Plus (Menzel-Gläser) microscope slides, and covered with preincubation medium comprising 1% normal goat serum (NGS), 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), PBT (0.1% Triton X-100 in 0.1M PBS, pH 7.4) for 1 h at room temperature to block unspecific binding sites. Immunohistochemistry was performed directly on this sectioned material. Slices were exposed to primary antibodies for 24 h at 4°C in the dark unless otherwise stated.

Drosophila

For antibody labeling, standard procedures were followed (Ashburner 1989). Briefly, dissected brains were fixed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, containing 4% paraformaldehyde for 25 – 30 min. They were then washed with 1x PBS, pH 7.4, containing 0.1 % Triton X-100 for 3 X 10 min. Samples were then incubated in blocking buffer (2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 1X PBS, pH 7.4, containing 0.1 % Triton X-100) for 1 hour at room temperature. They were then incubated with primary antibody diluted in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. They were subsequently washed 3 X 15 min in 1X PBS, pH 7.4, containing 0.1 % Triton X-100 at room temperature, followed by blocking buffer for 20 min. Samples were incubated with secondary antibody diluted in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C, followed by washes in 1X PBS, pH 7.4, containing 0.1 % Triton X-100 for 3 X 15 min, and mounting in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories).

For labeling of embryos, eggs were dechorionated and fixed in 4% formaldehyde containing PT (1% PBS, 0.3 % Triton X-100) with heptane. Embryos were then devitellinized in methanol and stored in ethanol prior to labeling with antibody, following the standard procedure (Ashburner 1989). Staging of embryos was based on morphological criteria (Campos-Ortega and Hartenstein 1997).

Primary antibodies

Grasshopper

anti-8B7

The monoclonal antibody 8B7 recognizes the Akt2 isoform of protein kinase B. The Akt2 kinase has an N-terminal (PH-) domain, a central kinase domain and a hydrophobic C-terminal domain with regulatory function. In grasshopper, the Akt2 kinase is expressed early in development in neuroblasts and their progeny, later in axonal projections (Seeger et al. 1993). The 8B7 primary antibody (gift of Dr. M. Bastiani) was diluted 1:200 in preincubation medium.

Anti-locustatachykinin (anti-LomTKII or anti-LTK)

The polyclonal anti-LomTK II antiserum (K1-50820091) was a gift from Dr. H. Agricola (Friedrich-Schiller-Universität, Jena). The antibody used is specific against common C terminals of LTK I and LTK II. For a full characterization see Wegerhoff et al. (1996) and Vitzthum and Homberg (1998). The antibody was diluted 1:10,000 in preincubation medium and embryo incubation was also for 24 h at 4°C in the dark.

Drosophila

The following primary antibodies were used: mouse anti-Neurotactin (Nrt, BP106; RRID:AB_528404), mouse anti-Neuroglian (Nrg, BP104; RRID:AB_528402), and rat anti-DNcadherin (DN-Ex #8; RRID:AB_2314331) antibodies from Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa; each diluted 1:10).

DN-cadherin

The antibody (DSHB DN-EX #8), a marker for neuropil, is a mouse monoclonal antibody raised against a peptide encoded by exon 8, amino acid residues 1210–1272 of the Drosophila CadN gene. The antibody detected two major bands, 300 kDa and 200 kDa molecular weights on Western blot of S2 cells only after transfection with a cDNA encoding the DN-cadherin protein (Iwai et al. 1997). In addition, the specificity of this antibody was tested with immunostaining of Drosophila embryos. Signal was hardly detectable in homozygous mutant, l(2)36DaM19 with nonsense mutation causes premature termination of protein translation. In contrast, this antibody gave a signal in mutant embryos with N-cadherin transgene.

Neurotactin

The antibody (DSHB BP106) labels secondary neurons and their axons. It is a mouse monoclonal antibody raised against the first 280 aminoterminal amino acid residues (Hortsch et al. 1990) of the Drosophila Nrt gene. The monoclonal antibody detected the same Drosophila embryonic pattern to that of a polyclonal antisera raised against a fusion protein using part of the Neurotactin cDNA (Hortsch et al. 1990). In addition, another monoclonal antibody, MAb E1C, against Neurotactin gave a similar expression pattern in Drosophila embryos to that of BP106 (Piovant and Léna 1988).

Neuroglian

The antibody (DSHB BP104) labels secondary neurons and axons in the adult brain. It is a mouse monoclonal antibody from a library generated against isolated Drosophila embryonic nerve cords (Bieber et al. 1989). The Nrg antibody was used to purify protein from whole embryo extracts by immunoaffinity chromatography. Protein microsequencing of the purified protein was performed to determine that the 18 N-terminal amino acids that is identical to the sequence determined for the N-terminus of the protein based on a full-length cDNA clone (Bieber et al. 1989).

Secondary antibodies

Grasshopper

After exposure to the primary antibody, sections were washed thoroughly in 0.1M PBS and then placed in preincubation medium (see above) to which the appropriate secondary antibody (for anti-8B7: GAM-Cy3, Sigma, 1:150 dilution; for anti-LTK: GAR-FITC, Dianova, 1:200 dilution) was added for 12 h at 4°C. Sections were then washed overnight in 0.1M PBS at 4°C in the dark, mounted in Vectashield® (Vector laboratories) on slides and coverslipped for microscopy. Specificity of the secondary antibody was confirmed by its application in the absence of the primary (in no case was a staining pattern observed).

Drosophila

For fluorescent staining, the following secondary antibodies were used: Alexa Fluor 546 goat anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) (#A11030; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA; used at 1:500) and Cy5 goat anti-Rat IgG (H+L) (112-175-143; Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA; used at 1:400).

Histology

Grasshopper

DAPI (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, Sigma) is a cell permeable fluorescent probe which binds to the minor groove of double-stranded DNA (Naimski et al. 1980). DAPI was diluted 1:100 in 0.1M PBS. Brain slices were exposed to DAPI for 30 min at room temperature, and this was followed by 6 washing cycles each of 20 min duration in 0.1M PBS.

Cell proliferation marker

Grasshopper

5-bromodeoxyuridine

5-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation was performed in whole embryo culture. Eggs were sterilized in 70% ethanol for 60 s, blotted dry on filter paper, and transferred for dissection into a solution of filtered sterilized insect medium (Mitsuhashi and Maramorosch, Sigma) supplemented with 10% FCS, Penicillin-Streptomycin (5 μl/ml) and 20-Hydroxyecdysone (150 μg/ml). The embryos were then incubated in a cell culture dish containing the above medium together with BrdU (final concentration 10−2 M). The incubation took place at 30°C with gentle agitation over pulses of 15–16 h (this represents approximately 3% of development for each stage examined). After incubation, embryos were restaged, fixed for 1 h in Pipes-FA, washed thoroughly in PBS, and their DNA denatured in a solution of 2 N HCL in PBS for 20 min.

For BrdU immunocytochemistry, embryos were incubated in a blocking solution of 0.4% PBT (PBS plus 0.4% Triton X-100), 5% NGS and 0.2% BSA for 45 min. The primary anti-BrdU antibody (Sigma) was diluted 1:200 in the blocking solution, and embryos maintained in this solution for 24 h at 4°C with gentle agitation. Embryos were then washed in 0.025% PBT (PBS plus 0.025% Triton X-100), and incubated in the secondary antibody (Dako EnVisionTM, goat anti-mouse, dilution 1:4 in PBS) at room temperature under gentle agitation for 15–16 h. Embryos were then washed in PBS, stained with DAB (DAB Fast tablets, Sigma) and the signal intensified by adding 0.02 M NiCl2. The reaction was stopped through several rinses with PBS. Preparations were viewed in 90% glycerol in PBS or embedded in Epon and sectioned at 20μm thickness.

Imaging

Grasshopper

Optical sections of preparations were acquired with a Leica TCS SP5 confocal laser scanning microscope equipped with x20 and x63 oil immersion objectives. Fluorochromes were visualized using an argon laser with excitation wavelengths of 405nm for DAPI, 488nm for FITC, 561nm for Cy3. Z-stacks of confocal images were collated using public domain software (Fiji), contrast and resolution altered where necessary, and false colors applied to the original monochrome images. Fluorescence photomicrographs were captured with a 1.3 MP color CCD camera (Scion Corp.) mounted on a Zeiss Axioskop 2 microscope and using Scion Visicapture™ software. Figure plates were generated with Canvas X™.

Drosophila

Embryos and larval brains labeled with antibody markers were viewed as whole-mounts by confocal microscopy [LSM 700 Imager M2 using Zen 2009 (Carl Zeiss Inc.); lenses: 40× oil (numerical aperture 1.3)]. Complete series of optical sections were taken from preparations between 1.2 and 2-μM intervals.

Nomenclature

Grasshopper

Neuroblasts were identified in the embryonic grasshopper brain according to Williams et al. (2005). The terminology of the tract system (w, x, y, z) is from Williams (1975). For convenience we label the neuroblasts whose progeny generate these tracts with the same name as the associated tract, but capitalized (W, X, Y, Z). The equivalences between the nomenclatures are: W = NB 1-1, X = NB 2-1, Y = NB 3-1, Z = NB 4-1. Nomenclature of embryonic commissural fascicles derives from a database of all commissures in the adult brain (Boyan et al. 1993) but with the letter “e” prior to the commissural name denoting an embryonic equivalent. For the grasshopper, the axes used for anatomical analysis in this study are neuraxes, not body axes. The top of the brain (in the adult head) is neurally anterior, the front of the brain is neurally ventral, the back of the brain is neurally dorsal, and the base of the brain is neurally posterior. Protocerebral bridge and fan-shaped body (upper division) are considered anterior to the ellipsoid body. Planes of section in the brain are defined with respect to the neuraxis, not the body axis: a frontal plane of section is parallel to the neuraxis, a horizontal plane of section is transverse to the neuroaxis.

Drosophila

Two parallel nomenclatures exist for the same type II lineages in the Drosophila brain. According to Pereanu and Hartenstein (2006), Wong et al. (2013) and Hartenstein et al. (2015) W = CM4, X = DPMpm2, Y = DPMpm1, and Z = DPMm1 respectively. A number of other authors (see citations in Riebli et al. 2013) on the other hand, refer to W = DM4, X = DM3, Y = DM2 and Z = DM1. In this study we will employ the CM4, DPMpm2, DPMpm1, DPMm1 system.

For Drosophila, the axes used for anatomical analysis and definition of planes of section are body axes. Note that according to body axis, the protocerebral bridge and fan-shaped body are located posteriorly of the ellipsoid body.

Results

In this study, we focus on a common set of lineages in the grasshopper and Drosophila which generate the w, x, y, z tracts that contribute fibers specifically to the columnar organization of the fan-shaped body. We identify the fascicles targeted by axons from this tract system and ascertain that a lineage-specificity exists which is conserved across these insects. Comparisons of this early projection pattern with that later in development allows us to identify the subset of commissural fascicles from which axons decussate en route across the midline, and we show that these generate a conserved tract-specific columnar neuroarchitecture in the fan-shaped body.

Neuroblasts, lineages, and the primordial commissural system of the protocerebrum

Prior to formation of the central complex, immunolabeling reveals the commissural system to be very similarly organized in both the grasshopper (Fig. 1a) and Drosophila (Fig 1b). A radial array of fiber tracts originating from multiple brain lineages projects axons towards the midline and so generates a system of commissural fascicles. Commissural axons remain within their fascicle of origin en route across the midline, but then diverge either to continue into the contralateral brain, or to descend to more posterior neuromeres (deutocerebrum, tritocerebrum) and then into the ventral nerve cord.

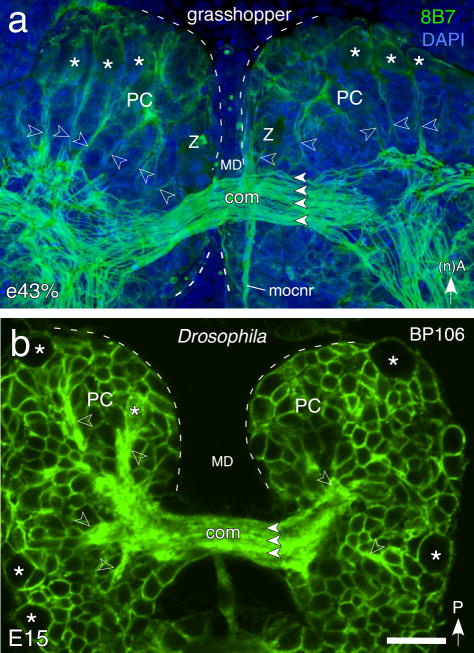

Fig. 1.

Axon scaffold of the early embryonic brain of the grasshopper and Drosophila prior to central complex formation. a. Confocal image of the grasshopper brain at 43% of embryogenesis (e43%) following double-labeling with 8B7 (green) and DAPI (blue) reveals the commissural fascicles (white arrowheads) making up the primary brain commissure (com) crossing the median domain (MD) and linking both protocerebral (PC) hemispheres (dashed white outline). Bilateral anterior cell clusters (white asterisks) generate fiber tracts (open white arrowheads) to the commissural system. Some axons descend directly to more posterior neuromeres (deutocerebrum, tritocerebrum) and then into the ventral nerve cord (not shown). Arrow points to anterior (A) according to the neuraxis (n). b. Confocal image of the brain of Drosophila at E15 following labeling with BP106 (green) reveals fiber tracts (open white arrowheads) from progeny of neuroblasts (white asterisks) and contributing to fascicles (white arrowheads) of the primary brain commissure (com) linking both protocerebral (PC) hemispheres (dashed white outline). Arrow points to posterior (P) according to the body axis. Other abbreviations: mocnr, median ocellar nerve tract. Scale bar represents 35μm in a and 20μm in b

In order to establish how this primordial commissural system ultimately contributes to the neuroarchitecture of the fan-shaped body, we had first to identify those fascicles whose axons could be traced to the W-Z lineages. Each protocerebral hemisphere of the grasshopper and Drosophila contains roughly 100 stem cells or neuroblasts (see Reichert and Boyan 1997). Of these, four - termed W, X, Y, Z - have been identified as generating progeny whose axons project via the w, x, y, z tracts to the protocerebral bridge and then to the midbrain where they form a columnar fiber system within the fan-shaped body (see Boyan and Reichert 2011). Note that W-Z include numerous other populations of neurons whose projections, some of them commissural, are outside the central complex (see Wong et al., 2013, for description of these projections in Drosophila). The location of W-Z in the protocerebrum of the grasshopper (Fig. 2a, b) and Drosophila (Fig. 2c) is stereotypic, and when viewed frontally, forms an almost linear array on either side of the brain midline. Confocal reconstructions of their lineages show these also have a stereotypic orientation in the protocerebrum which is also conserved (Fig. 2b, c).

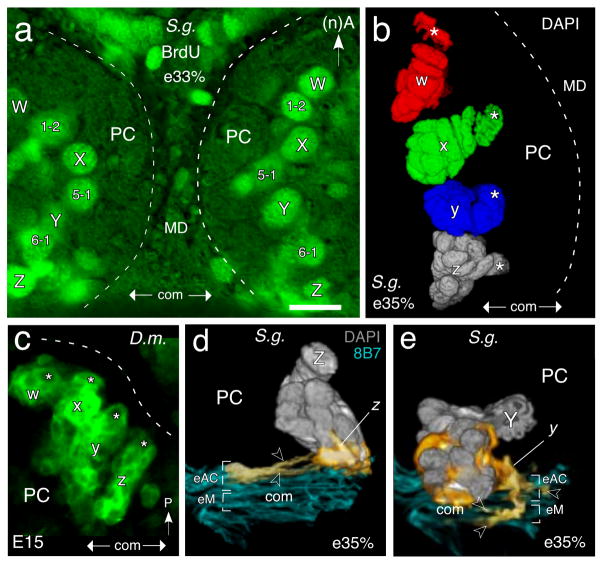

Fig. 2.

Neuroblasts, lineages and initial axon projections involved in fan-shaped body formation. a. Fluorescence photomicrograph of a brain slice from a grasshopper (S. g.) at 33% of embryogenesis (e33%) following BrdU incorporation (green) showing the most medial proliferative neuroblasts in each protocerebral hemisphere (PC, outlined dashed white). Note bilateral symmetry. Fibers from progeny of neuroblasts W, X, Y, Z will generate columns of the fan-shaped body later in embryogenesis. Progeny from identified neuroblasts (1–2, 5–1, 6–1) interspersed amongst the W, X, Y, Z neuroblasts do not contribute fibers to the columnar system of the fan-shaped body and so remain beyond the scope of this study. Approximate location of the primary brain commissure (com) is indicated in each panel. Anterior (A) is to the top according to the neuraxis (n) for the grasshopper (panels a, b, d, e). b. 3D reconstruction from confocal images following DAPI staining shows the W, X, Y, Z neuroblasts (white asterisks) and their lineages (false colors are used) in the left brain hemisphere of S. g. at 35% of embryogenesis (e35%). Lineages have a stereotypic orientation in the PC. c. Confocal image of the left protocerebral hemisphere (PC, outlined dashed white) of Drosophila (D.m.) following labeling of the W, X, Y, Z neuroblasts (white asterisks) and their primary lineages by R9D11-Gal4>UAS-mcd8-GFP at stage E15. Note similarity to the organization in grasshopper (panel b). Posterior (P) is to the top according to the body axis. d, e. Initial projections into the primary brain commissure from central complex lineages prior to formation of the fan-shaped body in the grasshopper. d. 3D reconstruction from confocal images following double-labeling with 8B7 (cyan) and DAPI (grey) reveals initial projections (open white arrowheads, false color yellow) from a Z lineage are into anterior fascicles (eAC) of the early embryonic (e35%) commissural system (com) of the grasshopper. Neuraxes apply for the grasshopper. e. As for d above but showing initial projections (open white arrowheads, false color yellow) from a Y lineage are into three anterior fascicles (eAC) as well as a medial fascicle (eM) of the early embryonic (e35%) commissural system (fasle color cyan) of the grasshopper. Axons in fascicles of eAC will contribute to the fan-shaped body which forms in the region of eM. Scale bar represents 25μm in a, b, 15μm in c, 15μm in d, e. Panels a, b are modified from Boyan and Liu (2016).

The stereotypic location of neuroblasts allows the axon projections associated with each lineage to be identified, and their route into the commissural system of the central brain via the w, x, y, z tracts to be traced. Our reconstructions in the grasshopper show that at 35% of embryogenesis, both the Z lineage (Fig. 2d) and the Y lineage (Fig. 2e) comprise approximately 25 progeny compared with over 100 progeny later (see Williams et al. 2005). Early outgrowing axons from the Z lineage have formed the initial z tract and project together into the central brain where they diverge to innervate two anterior commissural fascicles (according to the neuraxis) and which we propose represent the initial forms of AC III and AC VIII (Fig. 2d). No projections from the Z lineage to other commissural fascicles are seen at this early developmental stage, but the pattern changes subsequently (see Fig. 4 below). Initial fibers from the Y lineage also innervate three anterior fascicles (Fig. 2e) which we propose are the early embryonic (‘e’) forms of AC III, AC VIII and AC IX, as well as a more medial region which may be equivalent to the later eM system - a loose collection of commissural axons (see Boyan et al. 1993). According to the adult plan (c.f. Boyan et al. 1993), axons in eAC VIII and eAC IX will contribute to the columnar neuroarchitecture of the future fan-shaped body. In the adult, these columns traverse the eM system of commissural axons. Projections from both Z and Y lineages are consistent in being an anterior subset of fascicles, and there is a suggestion of lineage specificity within this early anterior system, a feature which is born out when examining later developmental stages (see Fig. 4 below).

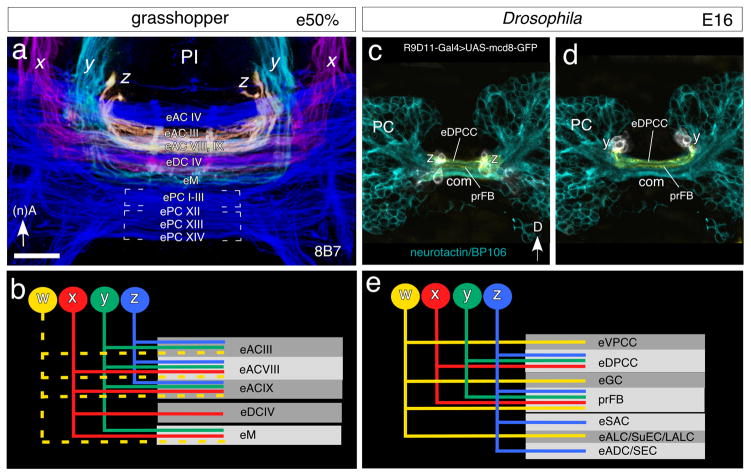

Fig. 4.

Identification of commissures innervated by axons from central complex tracts prior to formation of the fan-shaped body in the grasshopper (a, b) and Drosophila (c – e). a. 3D confocal image following 8B7 labeling shows superimposed axon projections from the z tract (yellow), y tract (cyan) and x tract (magenta) concatenated with the general commissural system (blue), as viewed frontally, and spanning the depths from 80–107μm in the embryonic (e50%) grasshopper brain (c.f. Fig. 3). Colors are false. The projections are localized to anterior commissures: eAC III, eAC VIII, eAC IX; the median commissural system eM; and the dorsal commissure eDC IV. No projections are found in embryonic posterior commissures at this stage. b. Schematic summarizes the pattern of axonal projections from the w, x, y, z system of tracts into identified commisssural fascicles of the grasshopper at e50%. The pattern of projections is lineage specific. Projections from the w tract (dashed yellow) are hypothesized based on the known adult plan (see Boyan et al. 1993). c. Confocal image of the protocerebrum of Drosophila at E16 shows cells of the Z lineage (white) labeled by R9D11-Gal4>UAS-mcd8-GFP with axons (orange) in dorsal fascicles (according to body axis) of the primary brain commissure (com). Fascicles with axons that will contribute to the mature fan-shaped body are indicated (prFB). General label for neurons is via neurotactin/BP106 (cyan). d. As for c above but for cells of the Y lineage (white) with processes (orange) in dorsal fascicles of the primary brain commissure (com). e. Schematic summarizes the pattern of axonal projections from the w, x, y, z system of tracts into identified commisssural fascicles in the brain of Drosophila at E16. Each of the four lineages generates neurons that contribute to different commissural tracts. One tract (prFB), receiving axons from all four lineages, will become incorporated into the fan-shaped body. The other tracts are the embryonic precursors (e) of different commissures (ADC anterior dorsal commissure; ALC antennal lobe commissure; DPCC dorsoposterior commissure of central complex; LALC lateral accessory lobe commissure; SAC superior arch commissure; SEC supraellipsoid body commissure; SuEC subellipsoid body commissure; VPCC ventroposterior commissure of central complex). Scale bar represents 15μm in a, 20μm in c, d

Projections from central complex lineages into the commissural system prior to fan-shaped body formation

The commissural organization of the midbrain is sufficiently established at mid-embryogenesis (Fig. 3) so that direct comparisons with the commissural plan for the adult brain are possible (c.f. Boyan et al. 1993). We traced the axon projections from each of the x, y, z tracts, as being representative of the general w, x, y, z system, into this embryonic commissural system as at 50% of embryogenesis – just prior to formation of the fan-shaped body. Our analysis covers four depths progressively from ventral (Fig. 3a, e, i) to more dorsal (Fig. 3d, h, l) through the brain where commissural fascicles can be shown to be innervated by axons from the x, y, z tracts, and thus are of relevance to fan-shaped body formation. Other commissures more ventral and dorsal in the brain (according to the neuraxis) were also identified, but are not included in this study as their axons do not participate in the establsihment of the tract-specific columnar neuroarchitecture of the fan-shaped body (see Boyan et al. 1993).

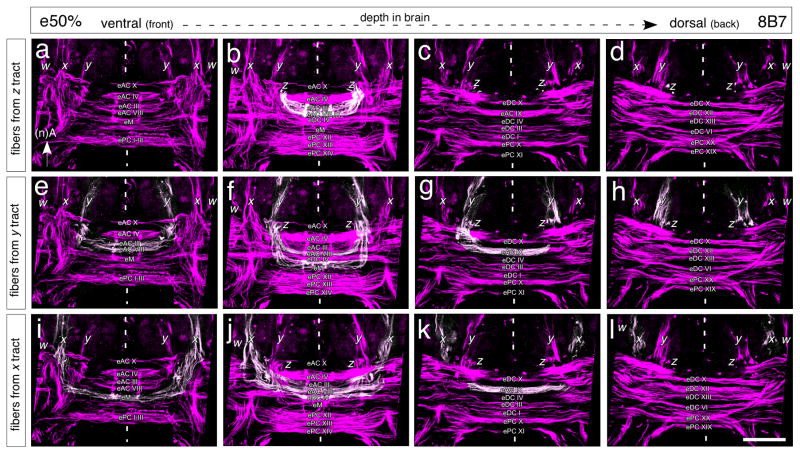

Fig. 3.

Axons from central complex lineages innervate unique combinations of commissural fascicles in the embryonic grasshopper brain. Panels represent concatenated confocal images of brain slices at four depths (a, e, i: 80–88μm; b, f, j: 90–98μm; c, g, k: 100μm; and d, h, l: 107μm) as measured from the ventral surface of the brain (according to the neuraxis) following 8B7 immunolabeling at 50% of embryogenesis (e50%) and prior to formation of the fan-shaped body. Axon projections (white) from the Z (a – d), Y (e – h) and X (i – l) tracts have been individually traced into the commissural system. Nomenclature of commissural fascicles follows that for the adult brain (Boyan et al. 1993). Scale bar represents 40μm

The axons from the bilateral x, y, z tracts innervate a restricted set of midbrain commissures and the projection pattern appears to be distinct for each lineage. Progeny from the Z lineage direct axons into anterior commissures which we propose are the embryonic (‘e’) equivalents of adult AC III, AC VIII and part of AC IX (Fig. 3a – d). Other commissures such as M appear not to be targeted (at least up to this age). The data here confirm the pattern reported for the Z lineage at 35% (c.f. Fig. 2d, e), and suggest that those anterior fascicles represent the initial embryonic forms of AC III and AC VIII. Progeny from the Y lineage also direct axons into the anterior commissures eAC III and eAC VIII, but additionally target eAC IX more extensively, as well as the eM system (Fig. 3e–h). eAC VIII and eAC IX are known to contain axons subsequently involved in fan-shaped body formation (see below). Axons from the X lineage innervate the same set of anterior commissures (eAC III, eAC VIII, eAC IX, and the eM system), but additionally target a fascicle we propose is equivalent to adult eDC IV which is involved in the formation of the noduli, also part of the central complex (see Boyan et al. 1993). We did not analyse the projections from the W lineage, but speculate that on the basis of the adult pattern (see Boyan et al. 1993) these will map onto those from the Z, Y, and X lineages with respect to eAC III, eAC VIII, eAC IX and eM.

The commissures we have identified as being innervated by the x, y, z tracts at 50% of embryogenesis in the grasshopper are shown superimposed in Figure 4a and summarized schematically in Figure 4b. Projections are symmetrical from the bilaterally homologous lineages in the protocerebral hemispheres, a prerequisite for the pattern of axogenesis known as fascicle switching which will generate a columnar system of the fan-shaped body shortly after (see below). We propose that the projections are localized to the anterior commissural group, in particular eAC III, eAC VIII, eAC IX, eM and eDC IV, but the combination of fascicles targeted appears to involve some lineage specificity: fascicles eAC VIII and eAC IX receive axons from all four tracts, eACIII from three (w, y, z), eM from three (w, x, y) and DCIV from one (x). We point out that the eAC VIII and eAC IX tracts, which are the only ones to receive axons from all four lineages, are also those that participate in the decussation process that generates the columnar neuroarchitecture of the FB.

In Drosophila, the large majority of cells forming the central complex are born postembryonically as secondary neurons (Pereanu and Hartenstein, 2010). This implies that most of the primary neurons of W-Z, which are born in the embryo, have axonal projections that will not become part of the central complex. Only a small number of primary W-Z neurons form a commissural fascicle that will be incorporated into the fan-shaped body (“primordium of the fan-shaped body; prFB; Riebli et al., 2013; Hartenstein et al., 2015). 3D-confocal reconstructions of the central brain following immunolabeling using the R9D11-Gal4 line at late embryonic stages (E16) show axons from the primary central complex lineages project into discrete fascicles of the primordial brain commissure (Fig. 4c, d). Identification of the individual fascicles innervated by each lineage as summarized schematically in Figure 4e shows a lineage specificity to exist, and allows some preliminary conclusions as to equivalences with the grasshopper system (c.f. Fig. 4b). Only fascicle prFB, which pioneers the fan-shaped body, receives axons from all four W-Z lineages. Other commissural elements that flank the prFB anteriorly or posteriorly are the eDPCC (receives axons from x, y, z), eVPCC and eGC (axons from z), eSAC and eADC/SEC (axons from w) and eALC/SuEC/LALC (axons from w).

Based on the similarities regarding innervation pattern and location within the commissure (when the axis orientations are transposed), and the fact that both these fascicles contain axons from homologous lineages and which will contribute to the tract-based columnar system of the fan-shaped body, it is now possible to speculate that eAC VIII and eAC IX of the grasshopper and prFB of Drosophila may represent homologous fascicles.

Origins of the columnar neuroarchitecture of the fan-shaped body

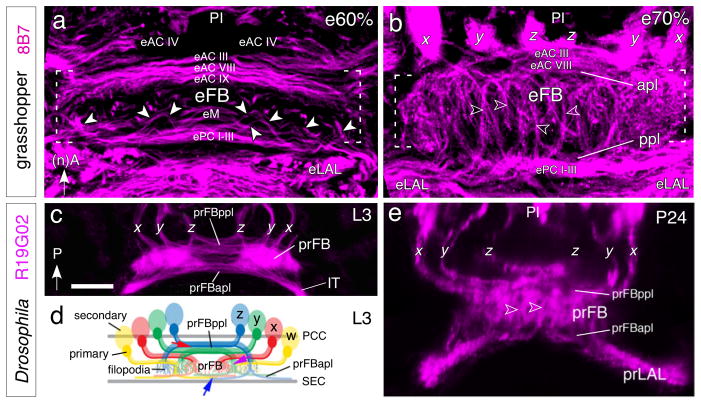

In the grasshopper, the axons of columnar neurons of the central complex enter the anterior surface of the fan-shaped body having first passed the protocerebral bridge where many of them form input (and, in part, output) synapses. Several classes of neurons terminate there (see Williams 1975; Heinze and Homberg 2008), but many continue towards the ellipsoid body, noduli, and lateral accessory lobe, located at the opposite (i.e., the posterior) side of the fan-shaped body (see Williams 1975; Heinze and Homberg 2008). These “trans-fan-shaped body axons” are organized in a metameric pattern of regularly spaced bundles that reflect the columnar organization of the fan-shaped body and ellipsoid body. The formation of these bundles is via axon decussation, and has been termed “fascicle switching” (Boyan et al. 2008b, 2015; Strausfeld 2012). In the grasshopper, the process of decussation begins after 55% of embryogenesis and transforms the previously purely orthogonal primary axon scaffold into a plexus-like neuroarchitecture. A comparison of the commissural organization prior to fascicle switching (at 50% of embryogenesis, Fig. 4a), with that at 60% of embryogenesis, by which stage elements of the fan-shaped body neuroarchitecture are already recognizable in the midline of the brain (Fig. 5a), confirms that axons decussate at stereotypic locations from a restricted subset of anterior commissures which we propose to comprise eAC VIII and eAC IX. These axons then turn posteriorly, passing across the loose commissural system termed eM to the posterior subset of commissures which we propose includes ePC I–III. Posterior commissures ePC I–III form the anterior border of the emerging ellipsoid body of the central complex (Fig. 5a) which in the adult lies between these and more posterior commissures such as PC XII, PC XIII and PC XIV (not visible here but see Boyan et al. 1993). By 70% of embryogenesis (Fig. 5b), decussated axons from the central complex tracts are now oriented more longitudinally in their projection en route across the eM region and both an anterior (apl) and posterior plexus (ppl) have formed.

Fig. 5.

The axon scaffold of the midbrain during formation of the fan-shaped body in the grasshopper (a, b) and Drosophila (c–e). a. At 60% of embryogenesis, 3D confocal image following 8B7 immunolabeling (magenta) reveals axon pathways in the central brain of the grasshopper at the commencement of embryonic fan-shaped body (eFB) formation. Axons (white arrowheads) from w, x, y, z tracts (not in picture) in the pars intercerebralis (PI) are in the process of decussating from anterior commissures eAC VIII and eAC IX across the eM region to innervate the more posterior commissures ePC I–III. These decussated axons form the basis of the tract-specific columns of the FB. The general form of the eFB (white dashed parentheses) is already apparent in the midbrain. Arrow points to anterior according to the neuraxis (nA) for the grasshopper panels. b. At 70%, confocal image shows that decussated axons from the x, y, z tracts (w is not visible in this brain slice) in the PI are now more orthogonal in their projection en route from the anterior plexus (apl) to the posterior plexus (ppl) of commissures. The columns (open white arrowheads) of the FB (white dashed parentheses) are now more apparent and the anterior and posterior commissures forming apl and ppl respectively are further apart in the brain than at 60%. c. Confocal image of the central brain of Drosophila at the late third larval (L3) stage following of the x, y, z tracts by R19G02-Gal4>UAS-mcd8-GFP (magenta) originating from cell clusters in the PI (not shown) and projecting into the commissural system of the developing primordial fan-shaped body (prFB). The primordial anterior plexus (prFBapl) and projections in the isthmus tract (IT) to the primordial lateral accessory lobes (not in picture) are evident. The tracts are organized as schematically shown in panel d. Axons from lineages y and z decussate. Arrow points to posterior (P) according to the body axis and applies to all Drosophila panels. d. Schematic summarizes the projection of axons from secondary w, x, y, z cell clusters into the developing prFB of the central brain at L3. Axons are in the process of decussating from the prFBppl (red arrow) to the prFBapl (blue arrow) thereby forming the initial columnar neuroarchitecture (purple arrow) of the FB. Commissural fascicles of the posterior commissures (PCC) of the central complex and superior ellipsoid body commissure (SEC) delimit the developing prFB. Filopodia from neurons terminating within the prFB are visible. e. Confocal image following R19G02 labeling (magenta) at 24 hrs after puparium formation (P24) shows axons projecting to the FB from secondary lineages in the PI via the x, y, z tracts. Axons have begun to decussate (see above) to form the initial columnar neuroarchitecture of the FB (open white arrowheads) between the prFBppl and the prFBappl. Scale bar in c represents 15μm in a, 20μm in b, c, e

In Drosophila (Figs. 5c–e), a similar process can be observed. As described above, subsets of axons formed by the four primary W-Z lineages converge upon a tight commissural bundle termed the primordium of the fan-shaped body (prFB; Riebli et al. 2013; Hartenstein et al. 2015; Lovick et al., 2017). At late larval stages, the primary axons of the prFB axons are joined by large numbers of axons from neurons which have proliferated secondarily (Fig. 5c, d). All axons form dense tufts of filopodia that greatly increase the volume of the fan-shaped body primordium, and that already foreshadow the columnar architecture of the adult fan-shaped body (Fig. 5c, d). Axons therefore make a 90° turn from their original transverse orientation to a longitudinal orientation and penetrate the fan-shaped body primordium at regular intervals, thus defining the columnar architecture of this structure. Axons destined for the ellipsoid body, noduli and lateral accessory lobes traverse the prFB and on reaching the opposite anterior side, project transversely again (Fig. 5c). During early pupal stages (Fig. 5e), the volume of the fan-shaped body grows rapidly and the decussating bundles increase in length concomitantly. A species comparison suggests that developmentally, the columnar neuroarchitecture present at e60% in the grasshopper approximates to that seen in the late third instar larva in Drosophila, while that present at grasshopper e70% is equivalent to that seen during mid-pupal stages in Drosophila.

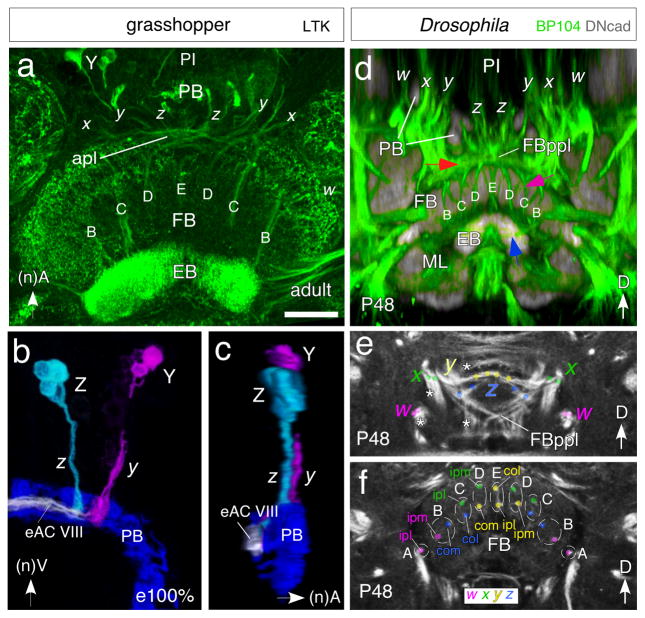

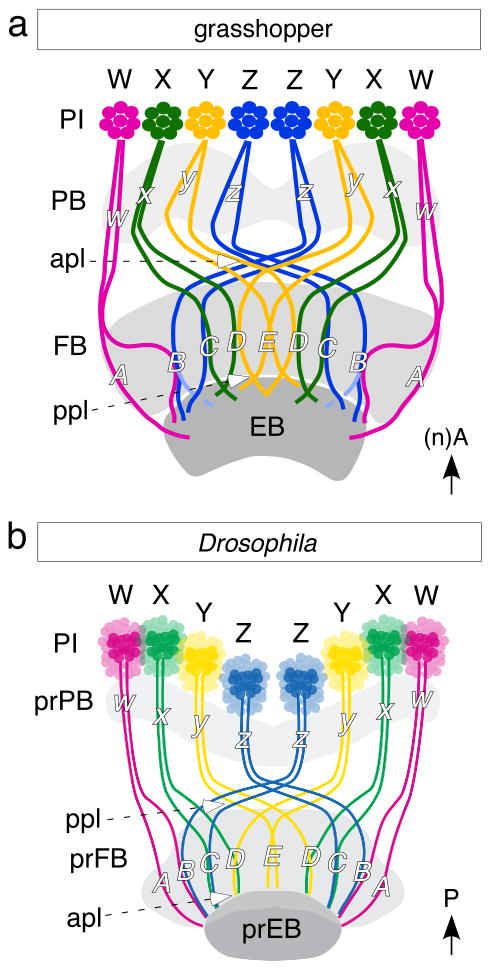

Conserved architecture of the trans-fan-shaped body fiber system

The metameric pattern of trans-fan-shaped body axon bundles is conserved in grasshopper and fly. Immunolabeling against locustatachykinin (LTK) reveals this pattern in the grasshopper brain (Fig. 6a–c). It comprises 9 fiber bundle-doublets termed A, B, C, D, E (Fig. 6a and see Fig. 7a), with each doublet composed of axons from a different combination of lineage-related neurons (see Fig. 7a). Each of the four paired lineages W–Z generates two bundles termed l (lateral) and medial (m) (see Fig. 7). Bundles pair up in such a way that doublet A is formed by the l axons of ipsilateral lineage W; doublet B contains medial axons of ipsilateral W and contralateral Z; doublet C lateral axons of ipsilateral X and contralateral Z; doublet D medial axons of ipsilateral X and contralateral Y; and doublet E lateral axons of ipsilateral and contralateral Y (see also Williams 1975).

Fig. 6.

Equivalent organization of tract-based columns in the FB of the grasshopper (a–c) and Drosophila (d–f). a. Confocal image of the central brain region of the adult grasshopper following locustatachykinin (LTK) immunolabeling reveals bilaterally symmetrical tract-specific columns (B, C, D, E) of the FB. Columns comprise axons from cell clusters in the PI projecting via the w, x, y, z system of tracts (x, y, z are visible here) through the PB into the anterior plexus (apl) from which they decussate to the EB. Neuraxes apply to grasshopper panels. b. 3D reconstruction from confocal optical slices following LTK immunolabeling at 100% of embryogenesis shows axons from a small cluster of LTK-positive cells at the equiavelnt location within each Z and Y lineage projecting through the PB and into fascicle eAC VIII of the commisural system. Axons project contralaterally across the midline where they will decussate to form tract-based columns (not shown). False colors have been applied, white indicates superposition of projections. Preparation is viewed from posterior. c. Same preparation as in b but rotated by 90° to reveal the position of fascicle eAC VIII with respect to the PB and z, y tracts. Axons are concurrent (white) in eAC VIII which is the first commissure posterior to the PB. d. Confocal image following double-immunolabeling (BP104, green; DNcad, grey) at the P48 stage of Drosophila reveals axons from lineages in the PI region projecting via the PB into the posterior plexus of the fan-shaped body (FBppl, red arrow) from which they decussate to form the tract-specific columnar system (B, C, D, E, purple arrow) of the FB. These axons then project further (blue arrow) to the EB. Body axes apply to Drosophila panels. Note the conserved projection pattern with that in the grasshopper (c.f. panel a). e, f. Confocal images following BP104 immunolabeling at the P48 stage of Drosophila reveals axon pathways in the central brain originating from w (magenta), x (green), y (yellow) and z (blue) lineages and that contribute to the columnar architecture of the FB. Both panels show frontal sections: (e) corresponds to a posterior level, illustrating the posterior plexus of the fan-shaped body (FBppl); (f) is more anterior at the level of the fan-shaped body (FB). White asterisks in (e) indicate tracts from the w, x, y, z lineages which do not project to the central complex. Colored dots in (e) and (f) demarcate the two bundles contributed by each of the four lineages to the central complex. Bundles of ipsilateral w (magenta) and x (green) and contralateral y (yellow) and z (blue) lineages approach each other as a result of decussation and form pairs corresponding to the A, B, C, D, E columns of the FB. Axon tracing (color coded) reveals that columns A–E comprise combinations of axons from ispsilateral lateral (ipl)-, ipsilateral medial (ipm)-, contralateral medial (com)- or contralateral lateral (col)- w, x, y or z lineages. Scale bar in a represents 80μm in a, 35μm in b, c, 25μm in d–f

Fig. 7.

Schematics (not to scale) summarize the conserved axonal projection patterns responsible for the tract-specific columns of the FB in the grasshopper (a) and Drosophila (b) In both species, axons originating from cell clusters belonging to the bilateral w, x, y, z lineages of the PI project via the PB to a plexus (apl in grassopper, ppl in Drosophila) and then decussate to form the 9 tract-specific columns (A-E) within the FB. These axons then exit the FB via another plexus (ppl in grasshopper, apl in Drosophila) en route to the EB. The columns comprise the identical combinations of tracts (A, w; B, w/z; C, x/z; D, x/y; E, y/y) in both grasshopper and Drosophila and so are evolutionarily conserved. Note the respective axis orientations.

In Drosophila, bundles of trans-fan-shaped body axons can be followed in mid-pupal brains labeled with the global marker anti-Neuroglian (BP104; Fig. 6d, e). Their pattern is largely identical to that in the grasshopper (c.f. Fig. 6a). Thus, each of the four W-Z lineages emits numerous closely related bundles of axons that project anteriorly (according to body axis), skirting the protocerebral bridge (Fig. 6d). Some bundles bypass the central complex, projecting into commissural or longitudinal systems towards different brain compartments, while others project into the posterior surface of the fan-shaped body, where they can no longer be followed individually. However, each lineage emits a pair of two closely apposed bundles which redistribute in the same manner as described above for grasshopper, forming doublets A-E that pass through the fan-shaped body to then decussate in the anterior plexus on their way towards the lateral accessory lobes.

Discussion

In both the grasshopper Schistocerca gregaria and Drosophila the fan-shaped body with its prominent columnar neuroarchitecture comprises the largest module of the adult central complex (see Strausfeld 2012). In the grasshopper, this columnar neuroarchitecture develops from an initially orthogonal primary axon scaffold during the second half of embryogenesis and is functional at the time of hatching (Boyan et al. 2008b, Boyan and Williams 2011). The neuroarchitecture is generated when subsets of axons from four lineages (termed W, X, Y, Z) in each protocerebral hemisphere innervate the existing commissural system but then decussate from anterior to more posterior lying fascicles at stereotypic locations across the central brain in a process known as “fascicle switching” (Boyan et al. 2008b, 2015). In Drosophila, decussation of axons from four putatively equivalent lineages to those of the grasshopper also occurs (Pereanu and Hartenstein 2006; Ito and Awasaki 2008; Pereanu et al. 2010; Young and Armstrong 2010; Riebli et al. 2013), but during the larval to pupal transition, so that the resulting neuroarchitecture is essentially an adult feature (Renn et al. 1999; Lovick et al. 2017). Species comparisons reveal that fascicle switching is present at some stage of development in the central brain of all arthropods and so may be considered a conserved mode of axogenesis (Strausfeld 2012; Boyan et al. 2015).

A major drawback in our understanding of axon decussation in the insect brain has been the lack of a systematic identification of the embryonic commissural fascicles involved. In the grasshopper, for example, although a map of all commissures for the adult brain has been available for some time (Boyan et al. 1993), the embryonic commissures have to date only been superficially allocated into anterior (ac) and posterior (pc) subsets (Boyan et al. 2008b, 2015), in keeping with the nomenclature for the early ventral nerve cord (see Goodman and Doe 1994). Further, while the pioneers of the w, x, y, z tracts from each protocerebral hemisphere have been shown to project into the primary commissural fascicle of the brain just after its formation early in embryogenesis and then to fasciculate with its pioneers (Williams et al. 2005), the early axons from the W, X, Y, Z lineages remain within the commissural fascicles they originally pioneer. Later ingrowing axons from these same lineages, however, subsequently decussate but the commissural fascicles involved have remained undescribed. In this study we have reconstructed the axon projections from representative lineages of the central complex into the commissural system of the brain at various developmental stages in both the grasshopper and Drosophila (Figs. 3–6). At the same time we have analysed the commissural organization itself at these stages (Figs. 4–6) using the nomenclature applicable to the grasshopper (Boyan et al. 1993) and Drosophila (Pereanu et al. 2010; Lovick et al., 2013). Our analysis leads us to the conclusion that in setting up the columnar neuroarchitecture of the fan-shaped body, comparable choices are being made by subsets of axons from equivalent lineages in both the grasshopper and Drosophila, consistent with a conserved wiring plan for this brain region.

Development of the midline neuroarchitecture

Grasshopper

At early embryonic stages (35%, Fig. 3), axons from central complex lineages are seen to project into subsets of commissural fascicles and we suggest that the innervation pattern indicates there is some lineage specificity present. However it is premature to attempt a definitive identification of these early fascicles beyond their belonging to the anterior subset in the brain. Many axons from other brain regions subsequently project across the brain midline and complement the initial fascicular plan (c.f. Fig. 1). Further, as noted above, the early axons from the w, x, y, z tracts remain within their original fascicles and do not decussate. This pattern of axogenesis is not a feature of all axons from later born cells and is only seen after mid-embryogenesis.

At mid-embryogenesis (50%), the commissural organization is sufficiently developed so as to allow a map to be constructed of at least those fascicles situated at the relevant depth (as seen ventral-dorsally) in the brain where decussation can be shown to commence shortly after (Figs. 4, 6). Our map shows that these fascicles can readily be allocated not only into anterior and posterior groups, but into discrete subsets organized in a recognizeably similar way to those in later stages (Boyan et al. 1993). We propose that the identification of those fascicles being innervated by axons from the w, x, y, z tracts is sufficiently certain so as to allow interpretations of how the midline neuroarchitecture develops in such later stages. Our proposal is that axons of lineages W-Z that contribute to the central complex columns traverse the brain midline within embryonic equivalents of commissures AC VIII, AC IX and M and then decussate to posterior commissures including PC I–III (Fig. 6c). There appear to be differences in the projection pattern into the commissural system from each lineage (Table I), and these may represent a lineage specificity. However, it is clear that the projection patterns we report at 50% of embryogenesis represent a “snapshot” within an ongoing developmental program. Lineage development in the W, X, Y, Z system is not completely synchronous, so that later axons from Z may well appear in eAC IX or eM. We do know from the adult plan, however (see Boyan et al. 1993), that all axons projecting to the protocerebral bridge and then the fan-shaped body from these lineages will innervate a restricted set of anterior commissures which are present at mid-embryogenesis and which we identify above.

Decussation commences shortly before 60% of embryogenesis, at which time the neuroarchitectural outlines of the fan-shaped body become obvious. As the neuropil of the developing fan-shaped body expands, the commissures immediately anterior of the fan-shaped body (AC III, VIII and IX) are deflected upwards and then flow as a “cupola” over it. Those commissures immediately posterior to (below) the fan-shaped body (PC I-III) flow between it and the developing ellipsoid body, thus forming the “floor” of the fan-shaped body and at the same time the “roof” of the ellipsoid body. The “floor” of the ellipsoid body is then formed by posterior commissures such as PC XII, III, IV (Fig. 6a,b). Single cell projections from subsets of LTK-positive neurons of the Z and Y lineages confirm a projection via the protocerebral bridge into AC VIII at the end of embryogenesis (Fig. 7), by which time the neuroarchitecture of the fan-shaped body is firmly established (Boyan et al. 2008a,b; Boyan and Williams 2011).

Drosophila

Axons pioneering the supraesophageal commissure in the mid- to late embryo define four bundles that, with respect to the centrally located medial lobe of the mushroom body, have been named dorso-anterior, dorso-posterior, ventro-anterior, and ventro-posterior commissures (Nassif et al. 1998; Nassif et al. 2003; Pereanu et al. 2010). At the early larval stage, distinct lineages with crossing axon tracts have been identified within these embryonic commissural systems (Hartenstein et al. 2015). Lineage-associated tracts which form the definitive fiber bundles (including commissures) of the Drosophila brain can be followed from larval to adult stages. It is therefore now possible to assign distinctive (adult) commissural identities to the four embryonic commissural systems as summarized in Fig. 4c–e (and see Lovick et al. 2013; Hartenstein et al. 2015). The ventro-anterior system includes the antennal lobe commissure (ALC; defined by lineages BAmd1/BAmd2), as well as the subellipsoid body commissure (SuEC, defined by DALcl1) and the lateral accessory lobe commissure (LALC, defined by CM1; the SuEC and LALC cannot yet be spatially separated in the late embryo/early L1). The ventro-posterior system has the great commissure (GC; defined by multiple commissural lineages, among them tracts of BLAv1/BLAv2 and BLVp1) and the posterior commissure of the postero-lateral protocerebrum (pPLPC; tracts of CM4 and CM3). Components that crystallize within the dorso-anterior system are the anterior-dorsal commissure (ADC; lineage DAMd1), the fronto-medial commissure (FrMC; lineages DALcm1/2 and BAmd1), the supra-ellipsoid body commissure (SEC; BLVp2) and the chiasm of the median bundle. Within the dorso-posterior system form the superior arch commissure (SAC), the superior commissure of the postero-lateral protocerebrum (sPLPC; DPLp1), the posterior commissures of the central complex (VPCC, DPCC), as well as the primordium of the fan-shaped body (prFB).

In contrast to the grasshopper, neural development in Drosophila is biphasic. Most primary neurons born in the embryo differentiate and form a fully functional larval brain. Neuroblasts enter a phase of quiescence that lasts until approximately 24h after larval hatching (Ito and Hotta, 1992; Lovick and Hartenstein, 2015). Subsequently, they start dividing again and generate secondary neurons. The w, x, y, z (CM4, DPMpm2, DPMpm1 and DPMm1, respectively) lineages proliferate as type II lineages, generating approximately 450 neurons each (Bello et al. 2008). Similar to their primary counterparts, secondary W, X, Y, Z lineages form multiple axon tracts (Pereanu and Hartenstein 2006; Cardona et al. 2010; Lovick et al. 2013; Yang et al. 2013), which are likely to correspond to the individual W, X, Y, Z sublineages. For each lineage, one pair of parallel, closely apposed tracts, joins the prFB.

In Drosophila, embryonically formed w, x, y, z axon bundles behave in a way that is comparable to that described for grasshopper. All four lineages generate primary neurons whose axons form multiple tracts that follow different pathways (Fig. 4, and see Hartenstein et al. 2015). As in the grasshopper, primary w, x, y, z tracts join several commissural systems (Fig. 4e). One commissural bundle that is joined by a small subset of fibers of all four lineages represents the so called primordium of the fan-shaped body (prFB; Riebli et al. 2013; Hartenstein et al. 2015; Riebli et al. in prep). Subsequently, during mid to late larval stages, a decussation, similar to that described for the 55% – 60% grasshopper embryo, takes shape in Drosophila (Fig. 5).

We can make several observations with respect to this development. First, the central complex (in particular the fan-shaped body primordium) has acquired a substantial volume at the late larval stage. The volume can be attributed to the secondary tracts described here (made by overall 500–800 neurons), as well as the tufts of filopodia formed by these neurons (Fig. 5d), rather than to additional differentiated neurons/synapses. Second, the decussating w, x, y, z axons (alongside the originally prFB visible already in the early larva, Fig. 5c, d) enter the fan-shaped body primordium at its posterior surface (anterior according to neuraxis in the grasshopper) (Fig. 6e for the 24h pupa). Here, the “decussation” begins (the pattern in the L3 larva is more compressed but similar). As in the grasshopper, the tracts in question comprise doublets (Fig. 7). The z doublet crosses far contralaterally, y crosses to a medial contralateral level. X does not cross the midline but bends medially and stays at a medial, ipsilateral level. W projects directly to a lateral ipsilateral level. In Drosophila, this matrix of tracts comprises the posterior plexus of the fan-shaped body [Fig. 7b;, anterior in the grasshopper (Fig. 7a)]. The pattern of axon projections reveals that once the double tracts reach their appropriate level in the medio-lateral axis, they bend anteriorly to traverse the voluminous fan-shaped body primordium towards its anterior (posterior in the grasshopper) surface (c.f. Fig. 6d). Once anterior, the tracts bend again and form the anterior plexus located dorsal of the ellipsoid body (referred to in the discussion above with respect to the grasshopper as the “floor” of the fan-shaped body). The 9 tract-specific columns (A-E) within the FB comprise the identical combinations of tracts (A, w; B, w/z; C, x/z; D, x/y; E, y/y) in both grasshopper and Drosophila and we propose that these are evolutionarily conserved.

If there is a substantial difference in decussation between Drosophila and the grasshopper it lies in two aspects:

the fact that in Drosophila, primary neurons already form a distinct “nucleus” of decussation that forms a distinct commissural bundle in prFB. Such an early precursor of decussation either does not exist in grasshopper, or can not yet be recognized without appropriate markers. Other than that, the behavior of the decussating fiber systems is very similar in both systems.

the presence in Drosophila of a voluminous, undifferentiated fan-shaped body primordium embedded in the center of the functioning larval brain. The primordium owes its existence to the fact that in holometabolous insects, large numbers of secondary neurons are formed that enter a state of “dormancy”, in which neurons possess simple fibers and filopodia, but do not form differentiated networks. This is different in hemimetabolans, like grasshopper, where all neurons proceed from birth to differentiation along an uninterrupted path. No larval stage where undifferentiated neurons coexist over a long time period with differentiated neurons exists.

Conserved organization of the central brain

In both Drosophila and the grasshopper, the axon scaffold of the embryonic brain comprises an orthogonal system of axonal projections around the stomodeum (see Reichert and Boyan 1997; Ito et al. 2014). Anterior to the stomodeum, this scaffold in Drosophila had earlier been resolved to the level of grouped anterior or posterior commissures, but not individual fascicles (Therianos et al. 1995; Nassif et al. 1998, 2003; Page 2004; Younossi-Hartenstein et al. 2006). Recent studies, using specific Gal-4 lines, on the other hand, have documented a large number of single projections from larval/pupal neurons of the protocerebrum to the protocerebral bridge and then to the fan-shaped body, ellipsoid body and noduli, many of a commissural nature (Illius et al. 1994; Pereanu and Hartenstein 2006; de Velasco et al. 2007; Ito and Awasaki 2008; Pereanu et al. 2010; Young and Armstrong 2010; Riebli et al. 2013; Ito et al. 2014; Wolff et al. 2015). Such commissural elements may now be integrated into a plan equivalent to that developed for the grasshopper.

The conserved nature of fan-shaped body neuroarchitecture in insects such as Drosophila and the grasshopper makes it likely that there is also a high degree of correspondence among their commissural fascicles (Strausfeld 2012; Ito et al. 2014). Our study now enables the development of the fan-shaped body to be understood at the level of individually identified commissural fascicles, and so provides the basis for interspecific comparisons of central complex development involving Drosophila (Renn et al. 1999; Young and Armstrong 2010; Riebli et al. 2013), Tenebrio (Wegerhoff and Breidbach 1992; Wegerhoff et al. 1996) and the sightless dipluran Campodea (Böhm et al. 2012) where similar patterns of axon decussation are found. Equally, mutant analyses in Drosophila may allow the pattern of decussation present in the grasshopper to be understood with greater precision. For example, the topographic decussation of axons at stereotypic locations in both species suggests the presence of choice points across the midbrain similar to that reported for the ventral nerve cord (Kaprielian et al. 2001). Although the mechanism has yet to be identified in the brain, a dysregulation of cell surface adhesion/recognition molecules in a graded manner across the midbrain represents one possibility. In the peripheral nervous system of Drosophila mutant for the cell surface molecule fasciclin III, for example, axons switch fascicles to an incorrect branch of the segmental nerve and so project to inappropriate body wall muscles (Snow et al. 1989; Goodman and Doe 1994), while in the visual system, relative expression levels of adhesion molecules have been found to regulate the wiring of neurite fascicles (Schwabe et al. 2014). Glia have also been shown to direct neuronal axogenesis in the CNS (Jacobs and Goodman 1989; Nordermeer et al. 1998; Hidalgo and Booth 2000) and midline glia are present in the both the grasshopper and Drosophila brain during commissure formation (Boyan et al. 1995; Therianos et al. 1995; Reichert and Boyan 1997; Page 2004; Lovick et al. 2017). In the karussell mutant, for example, dysregulation of midline glia belonging to the pointed group results in commissural axons of the ventral nerve cord decussating between anterior and posterior fascicles, a neuroarchitecture not found in the wild type (Hummel et al. 1999).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. J.L.D. Williams for enlightening discussions and Karin Fischer for excellent technical assistance. Financial support was from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (BO 1434/3-5) and the Graduate School of Systemic Neuroscience, LMU. Y.L. received support from LMU Munich’s Institutional Strategy “LMUexcellent” within the framework of the German Excellence Initiative. V.H. was supported by NIH grant R01 NS054814.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. All experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines for animal welfare as laid down by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

References

- Ashburner M. Drosophila: A laboratory handbook and manual. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bello BC, Izergina N, Caussinus E, Reichert H. Amplification of neural stem cell proliferation by intermediate progenitor cells in Drosophila brain development. Neural Dev. 2008;3:5. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley D, Keshishian H, Shankland M, Torian-Raymond A. Quantitative staging of embryonic development of the grasshopper, Schistocerca nitens. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1979;54:47–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieber AJ, Snow PM, Hortsch M, Patel NH, Jacobs JR, Traquina ZR, Schilling J, Goodman CS. Drosophila neuroglian: a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily with extensive homology to the vertebrate neural adhesion molecule L1. Cell. 1989;59:447–460. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhm A, Szucsich NU, Pass G. Brain anatomy in Diplura (Hexapoda) Front Zool. 2012;9:26. doi: 10.1186/1742-9994-9-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyan GS, Reichert H. Mechanisms for complexity in the brain: generating the insect central complex. Trends Neurosci. 2011;34:247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyan GS, Williams JLD. Embryonic development of the pars intercerebralis/central complex of the grasshopper. Dev Genes Evol. 1997;207:317–329. doi: 10.1007/s004270050119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyan GS, Williams L. Embryonic development of the insect central complex: insights from lineages in the grasshopper and Drosophila. Arthr Struct Dev. 2011;40:334–348. doi: 10.1016/j.asd.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyan GS, Liu Y. Development of the neurochemical architecture of the central Complex. Front Behav Neurosci. 2016;10:1. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2016.00167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyan GS, Williams JLD, Herbert Z. An ontogenetic anaysis of locustatachykinin-like expression in the central complex of the grasshopper Schistocerca gregaria. Arthr Struct Dev. 2008a;37:480–491. doi: 10.1016/j.asd.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyan GS, Williams JL, Herbert Z. Fascicle switching generates a chiasmal neuroarchitecture in the embryonic central body of the grasshopper Schistocerca gregaria. Arthr Struct Dev. 2008b;37:539–544. doi: 10.1016/j.asd.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyan G, Williams L, Liu Y. Conserved patterns of axogenesis in the panarthropod brain. Arthr Struct Devel. 2015;44:101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.asd.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyan G, Williams L, Meier T. Organization of the commissural fibers in the adult brain of the locust. J Comp Neurol. 1993;332:358–377. doi: 10.1002/cne.903320308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyan GS, Therianos S, Williams JLD, Reichert H. Axogenesis in the embryonic brain of the grasshopper Schistocerca gregaria: An identified cell analysis of early brain development. Development. 1995;121:75–86. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Ortega JA, Hartenstein VH. The embryonic development of Drosophila melanogaster. 2. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Cardona A, Saalfeld S, Arganda I, Pereanu W, Schindelin J, Hartenstein V. Identifying neuronal lineages of Drosophila by sequence analysis of axon tracts. J Neurosci. 2010;30:7538–7553. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0186-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Velasco B, Erclik T, Shy D, Sclafani J, Lipschitz H, McInnes R, Hartenstein V. Specification and development of the pars intercerebralis and pars lateralis, neuroendocrine command centers in the Drosophila brain. Dev Biol. 2007;302:309–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el Jundi B, Heinze S, Lenschow C, Kurylas A, Rohlfing T, Homberg U. The locust standard brain: a 3D standard of the central complex as a platform for neural network analysis. Front Syst Neurosci. 2010;3:21. doi: 10.3389/neuro.06.021.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman CS, Doe CQ. Embryonic development of the Drosophila central nervous system. In: Bate M, Martinez-Arias A, editors. The development of Drosophila. Vol. 1. Cold Spring Harbor Press; New York: 1994. pp. 1131–1206. [Google Scholar]

- Harley CM, Ritzmann RE. Electrolytic lesions within central complex neuropils of the cockroach brain affect negotiation of barriers. J Exp Biol. 2010;231:2851–2864. doi: 10.1242/jeb.042499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartenstein V, Younossi-Hartenstein A, Lovick JK, Kong A, Omoto JJ, Ngo KT, Viktorin G. Lineage-associated tracts defining the anatomy of the Drosophila first instar larval brain. Dev Biol. 2015;406:14–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinze S, Homberg U. Maplike representation of celestial e-vector orientations in the brain of an insect. Science. 2007;315:995–997. doi: 10.1126/science.1135531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinze S, Homberg U. Neuroarchitecture of the central complex of the desert locust: intrinsic and columnar neurons. J Comp Neurol. 2008;511:454–478. doi: 10.1002/cne.21842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo A, Booth GE. Glia dictate pioneer axon trajectories in the Drosophila embryonic CNS. Development. 2000;127:393–402. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.2.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homberg U. Structure and functions of the central complex in insects. In: Gupta AP, editor. Arthropod brain: its evolution, development, structure, and functions. Wiley Press; New York: 1987. pp. 347–367. [Google Scholar]

- Hortsch M, Patel NH, Bieber AJ, Traquina ZR, Goodman CS. Drosophila neurotactin, a surface glycoprotein with homology to serine esterases, is dynamically expressed during embryogenesis. Development. 1990;110:1327–1340. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.4.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel T, Schimmelpfeng K, Klämbt C. Commissure formation in the embryonic CNS of Drosophila. II. Function of the different midline cells. Development. 1999;126:771–779. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.4.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilius M, Wolf R, Heisenberg M. The central complex of Drosophila melanogaster is involved in flight control: studies on mutants and mosaics of the gene ellipsoid body open. J Neurogenet. 1994;9:189–206. doi: 10.3109/01677069409167279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Hotta Y. Proliferation pattern of postembryonic neuroblasts in the brain of Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol. 1992;149:134–48. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90270-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Awasaki T. Clonal unit architecture of the adult fly brain. In: Technau GM, editor. Brain Development in Drosophila melanogaster. Springer; New York: 2008. pp. 137–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M, Masuda N, Shinomiya K, Endo K, Ito K. Systematic analysis of neural projections reveals clonal composition of the Drosophila brain. Curr Biol. 2013;23:644–655. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Shinomiya K, Ito M, Armstrong JD, Boyan G, Hartenstein V, Harzsch S, Heisenberg M, Homberg U, Jenett A, Keshishian H, Restifo LL, Rössler W, Simpson JH, Strausfeld NJ, Strauss R, Vosshall LB. A systematic nomenclature for the insect brain. Neuron. 2014;81:755–765. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai Y, Usui T, Hirano S, Steward R, Takeichi M, Uemura T. Axon patterning requires DN-cadherin, a novel neuronal adhesion receptor, in the Drosophila embryonic CNS. Neuron. 1997;19:77–89. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JR, Goodman CS. Embryonic development of axon pathways in the Drosophila CNS. I. A glial scaffold appears before the first growth cones. J Neurosci. 1989;9:2402–2411. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-07-02402.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaprielian Z, Runko E, Imondi R. Axon guidance at the midline choice point. Dev Dynamics. 2001;221:154–181. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koniszewski NDB, Kollmann M, Bigham M, Farnworth M, He B, Büscher M, Hütteroth W, Binzer M, Schachtner J, Bucher G. The insect central complex as model for heterochronic brain development—background, concepts, and tools. Dev Genes Evol. 2016;226:209–219. doi: 10.1007/s00427-016-0542-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Seiler H, Wen A, Zars T, Ito K, Wolf M, Heisenberg M, Liu L. Distinct memory traces for two visual features in the Drosophila brain. Nature. 2006;439:551–556. doi: 10.1038/nature04381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loesel R, Nässel DR, Strausfeld NJ. Common design in a unique midline neuropil in the brains of arthropods. Arthr Struct Dev. 2002;31:77–91. doi: 10.1016/S1467-8039(02)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovick JK, Ngo KT, Omoto JJ, Wong DC, Nguyen JD, Hartenstein V. Postembryonic lineages of the Drosophila brain: I. Development of the lineage-associated fiber tracts. Dev Biol. 2013;384:228–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovick JK, Hartenstein V. Hydroxyurea-mediated neuroblast ablation establishes birth dates of secondary lineages and addresses neuronal interactions in the developing Drosophila brain. Dev Biol. 2015;402:32–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovick JK, Omoto JJ, Ngo KT, Hartenstein V. Development of the anterior visual input pathway to the Drosophila central complex. J Comp Neurol. 2017 doi: 10.1002/cne.24277. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naimski P, Bierzyimageski A, Fikus M. Quantitative fluorescent analysis of different conformational forms of DNA bound to the dye 4′, 6-diamidine-2-phenylindole, and separated by gel electrophoresis. Anal Biochem. 1980;106:471–475. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90550-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassif C, Noveen A, Hartenstein V. Embryonic development of the Drosophila brain I. The pattern of pioneer tracts. J Comp Neurol. 1998;402:10–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassif C, Noveen A, Hartenstein V. Early development of the Drosophila brain III. The pattern of neuropile founder tracts during the larval period. J Comp Neurol. 2003;455:417–434. doi: 10.1002/cne.10482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuser K, Triphan T, Mronz M, Poeck B, Strauss R. Analysis of a spatial orientation memory in Drosophila. Nature. 2008;453:1244–1247. doi: 10.1038/nature07003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noordermeer JN, Kopczynski CC, Fetter RD, Bland KS, Chen WY, Goodman CS. Wrapper, a novel member of the Ig superfamily, is expressed by midline glia and is required for them to ensheath commissural axons in Drosophila. Neuron. 1998;21:991–1001. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80618-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page DT. A mode of arthropod brain evolution suggested by Drosophila commissure development. Evol Develop. 2004;6:25–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142x.2004.04003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y, Zhou Y, Guo C, Gong H, Gong Z, Liu L. Differential roles of the fan-shaped body and the ellipsoid body in Drosophila visual pattern memory. Learn Mem. 2009;16:289–295. doi: 10.1101/lm.1331809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereanu W, Hartenstein V. Neural lineages of the Drosophila brain: a three-dimensional digital atlas of the pattern of lineage location and projection at the late larval stage. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5534–5553. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4708-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereanu W, Kumar A, Jennett A, Reichert H, Hartenstein V. Development-based compartmentalization of the Drosophila central brain. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:2996–3023. doi: 10.1002/cne.22376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer K, Homberg U. Organization and functional roles of the central complex in the insect brain. Ann Rev Entomol. 2014;59:165–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-011613-162031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piovant M, Léna P. Membrane glycoproteins immunologically related to the human insulin receptor are associated with presumptive neuronal territories and developing neurones in Drosophila melanogaster. Development. 1988;103:145–156. doi: 10.1242/dev.103.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichert H, Boyan GS. Building a brain: insights from insects. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:258–264. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)01034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renn SCN, Armstrong JD, Yang M, Wang Z, An X, Kaiser K, Taghert PH. Genetic analysis of the Drosophila ellipsoid body neuropil: organization and development of the central complex. J Neurobiol. 1999;41:189–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riebli N, Viktorin G, Reichert H. Early-born neurons in type II neuroblast lineages establish a larval primordium and integrate into adult circuitry during central complex development in Drosophila. Neural Develop. 2013;8:6. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-8-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwabe T, Borycz JA, Meinertzhagen IA, Clandinin TR. Differential adhesion determines the organization of synaptic fascicles in the Drosophila visual system. Curr Biol. 2014;24:1304–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.04.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]