Abstract

Background/Objectives

The psychological impact of alopecia areata is well documented, but group interaction may help lessen this burden. We aimed to determine factors which draw patients with alopecia areata and their families to group events.

Methods

Surveys were administered at the Annual Alopecia Areata Bowling Social in 2015 and 2016. This event is a unique opportunity for children affected by alopecia areata and their families to meet others with the disease and connect with local support group resources from the Minnesota branch of the National Alopecia Areata Foundation. Data from 2015 and 2016 were combined. Comparisons between subgroups were carried out using Fisher’s exact test for response frequencies and percentages, and two sample t-test for mean values.

Results

An equal number of males and females participated in the study (n = 13, each) with an average age of 41.1 years. There were no significant differences (p > 0.05) in survey responses based on respondent age or gender. Most (23/26, 88.5%) attendees sought to connect with others affected by alopecia areata and met 3 or more people during the event (23/26, 88.5%). Many also attended other support group events (17/26, 65.4%). Almost half of respondents (12/26, 46.2%) came to support a friend or family member. One hundred percent of attendees identified socializing with others with alopecia areata as important.

Conclusions

Group interaction is an important source of therapeutic support in patients and families affected by alopecia areata.

Keywords: Alopecia areata, Pediatrics, Group interaction, Psychology, Survey

Introduction

The psychological sequelae for some patients with alopecia areata (AA) have been well documented in the literature, including increased risk of anxiety, depression, social phobias, paranoid disorders, self-esteem issues, decreased body image, and reduced quality of life. (1–4) Comprehensive therapeutic support for AA may include monitoring and treatment for psychiatric issues due to their prevalence in those diagnosed. (5, 6) Mounting evidence supports that involvement with support groups and other group activities enhances coping strategies, creates a sense of belonging and can improve quality of life. (7) There is little such evidence substantiating the importance of these group events for those with hair and skin disorders. To address this, we organized the Alopecia Areata Bowling Social for children affected by AA and their families.

The Alopecia Areata Bowling Social is an opportunity to connect pediatric patients with AA and their families to others in the local community through an evening of bowling, socializing and accessibility to local support group resources. It is advertised to current members of the Minnesota branch of the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (NAAF) support group as well as to pediatric patients with alopecia areata seen at the University of Minnesota Department of Dermatology Clinics. The event is organized by the University of Minnesota Dermatology Interest Group and supported by the Department of Dermatology. The event includes: bowling, complimentary pizza dinner, interactive games, prizes for all children attending, photo booth, local support group leadership presence, and local support group informational handouts. See Table 1 for event development details. To assess the appeal of this pediatric group event, we administered surveys to parents of children with AA attending the Bowling Social during 2015 and 2016.

Table 1.

Event How To

|

NAAF: National Alopecia Areata Foundation

Materials and Methods

Study Population

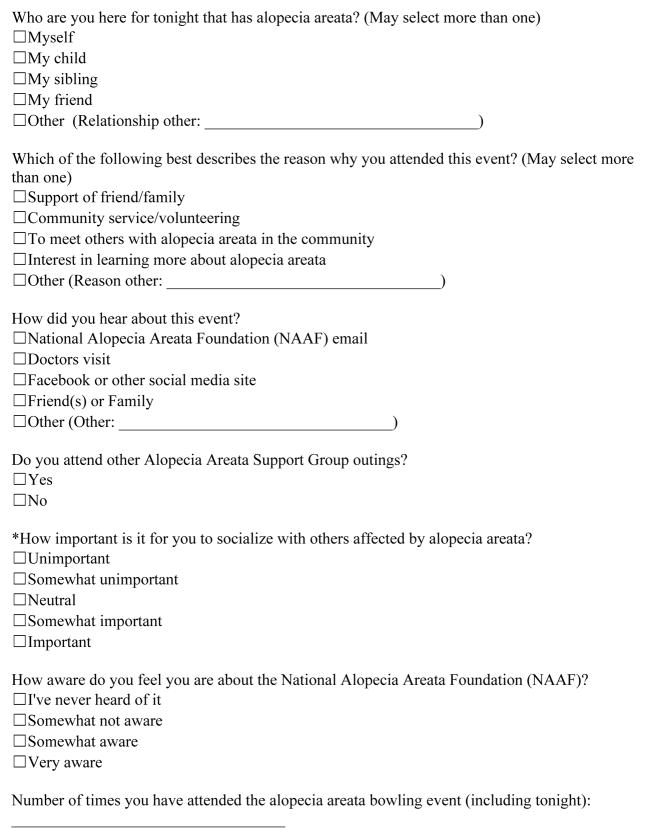

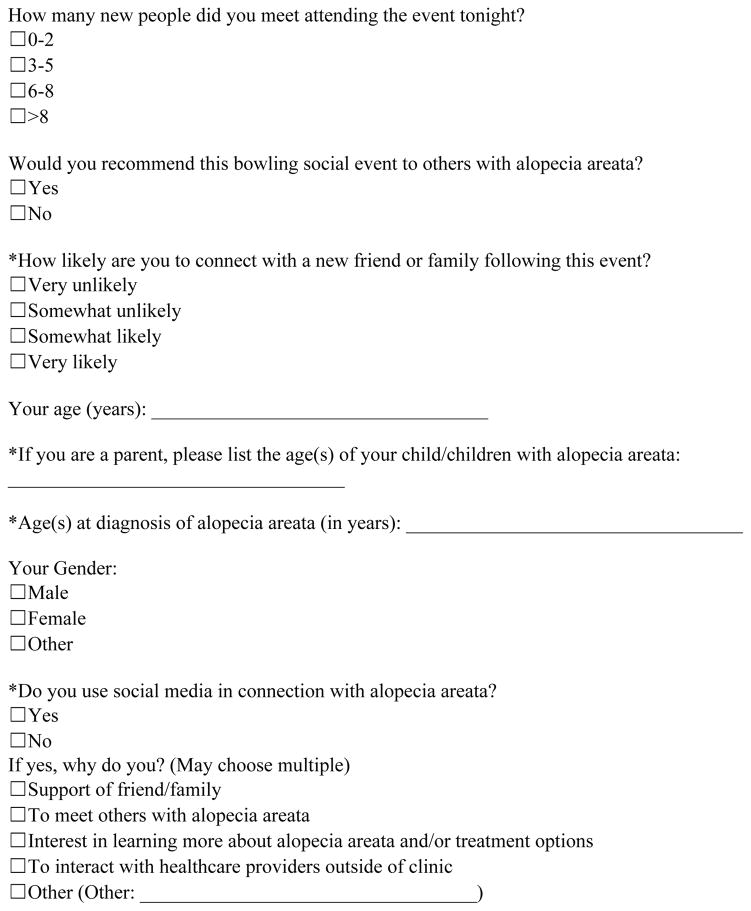

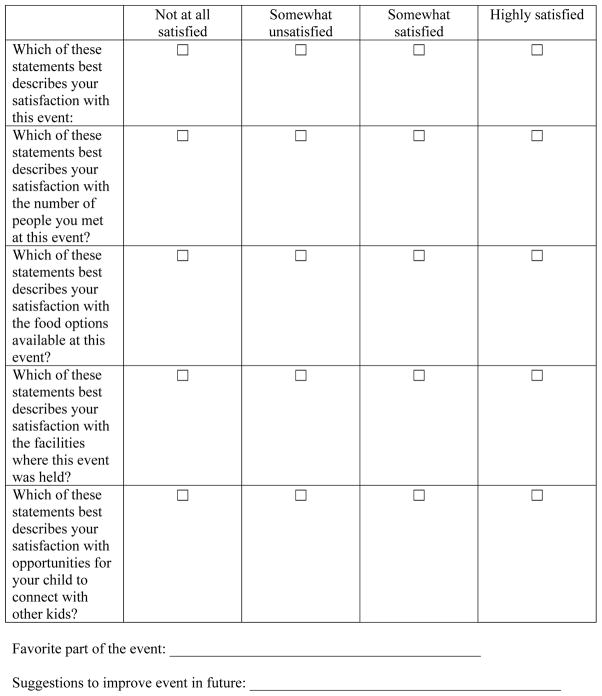

An adult representative (age ≥ 18) from each family attending the Annual Alopecia Areata Bowling Social was invited to participate in the survey. See Figure 1 for full list of survey questions. Of the 18 families present in 2015, 15 responded (83.3%) and in 2016, out of the 12 families present, 11 responded (91.7%); there were a total of 26 respondents between the two years. All respondents were the first or second-degree family member of a child with AA. Participation was voluntary and anonymous.

Figure 1.

Survey Questions.

*Indicates new questions added in 2016.

Data Collection

Survey responses were recorded in the Research Electronic Capture (REDCap) system, a secure web-based application. (8) Responses from both years were combined into an Excel spreadsheet (2011, Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA).

Statistical Methods

Summary statistics and data analysis were provided by the Biostatistics Design and Analysis Center (BDAC) of the University of Minnesota Clinical and Translational Science Institute. Frequencies and percentages were compared between genders using Fisher’s exact test. Mean values were compared between subgroups using the two sample t-test.

This study was given exempt status from the University of Minnesota Human Subjects Institutional Review Board

Results

Demographics

After combining responses from 2015 and 2016, there was an equal number of males and females participating in the survey (n = 13, each). The average age of survey respondents was 41.1 years, ranging from 30–52 years. There was no statistically significant difference between survey responses based on the gender or age of the individual participating (Table 2, Table 3). In 2016, additional questions regarding the age of children at the event were included. Of the children attending (age < 18), the average age was 9.2 years (range 5–16 years, n = 13), and the mean age at diagnosis of AA was 3.5 years (range 8 months–9 years).

Table 2.

Survey Responses by Gender of Adult

| Male | Female | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Variable | x/n (%) | x/n (%) | P-value |

| Attended other AA support group events | 9/13 (69.2%) | 8/13 (61.5%) | 1.00 |

| Attended to support family/friend | 6/13 (46.2%) | 6/13 (46.2%) | 1.00 |

| Attended to meet others with AA | 11/13 (84.6%) | 12/13 (92.3%) | 1.00 |

| Attended to meet others but not support family/friend | 6/12 (50.0%) | 7/13 (53.9%) | 1.00 |

| Number of people met at event: | |||

| 0–2 | 2 (15.4%) | 1 (7.7%) | |

| 3–5 | 7 (53.8%) | 7 (53.8%) | 0.667 |

| 6–8 | 4 (30.8%) | 3 (23.1%) | |

| >8 | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (15.4%) | |

| Mean (range) | Mean (range) | ||

|

| |||

| Number of times attended this event | 2.7 (1–6) | 2.0 (0–4) | 0.246 |

| Age in years* | 40.8 (30–52) | 41.4 (36–48) | 0.747 |

Two people did not provide an age as a single year.

AA: Alopecia areata

Table 3.

Survey Responses by Age of Adult

| Variable | Mean age (range) | n* | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attended other AA support group events: | |||

| Yes | 42.0 (36–52) | 16 | 0.202 |

| No | 39.3 (30–46) | 8 | |

| Attended to support family/friend: | |||

| Yes | 40.9 (36–48) | 12 | 0.873 |

| No | 41.3 (30–52) | 12 | |

| Attended to meet others with AA: | |||

| Yes | 41.1 (33–52) | 21 | 0.988 |

| No | 41.0 (30–48) | 3 | |

| Attended to only meet others with AA: | |||

| Yes | 42.3 (33–52) | 11 | 0.473 |

| No | 40.9 (36–48) | 12 | |

Two people did not provide an age as a single year, hence total n less than 26.

AA: Alopecia areata

Perception of Group Interaction

The majority of attendees (23/26, 88.5%) participated in the group event to meet others with AA and most (23/26, 88.5%) met 3 or more people (Table 2). Most respondents had also participated in other AA support group events (17/26, 65.4%) and several attended the bowling social in support of a friend or family member (12/26, 46.2%, Table 2). To specifically address the importance of interacting with others with AA, we added three survey questions in 2016 (Table 4). All respondents reported that it was important to socialize with others affected by AA and most (9/11, 81.8%) believed they were likely to connect with someone new from this event (Table 4). Additionally, 45.5% (5/11) of parents reported that they used social media (Table 4) to meet others with AA (4/5, 80/0%), support friends/family (2/5, 40.0%), and learn more about AA and/or treatment options (2/5, 40.0%).

Table 4.

Additional 2016 Survey Questions

| Yes† | No§ | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Variable | n (%)* | n (%)* |

| Important to socialize with others with AA | 11 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Likely to connect with someone new from this event | 9 (81.8) | 2 (18.2) |

| Use social media in connection to AA | 5 (45.5) | 6 (54.5) |

Includes responses of “important”, “somewhat important”, “very likely”, “somewhat likely”, and “yes”.

Includes responses of “unimportant”, “somewhat unimportant”, “neutral”, “very unlikely”, “somewhat unlikely”, and “no”.

Response rate for 2016 was 11/12, and 11 is the denominator for the (%).

AA: Alopecia areata

Discussion

For pediatric AA patients and their families, the psychological morbidity of AA may manifest early. Children and adolescents with AA may demonstrate higher levels of anxiety and lower parent-rated psychosocial quality of life levels. (9) In this study, building a foundation of peer support early is self-reported as an important part of coping with the disease. The majority of adult parents (88.5%) endorsed that meeting others with AA was an important reason their family attended and achieved this goal by meeting at least 3 new individuals during the bowling social (88.5%).

Pediatric patients with AA may also have a relative deficiency of peer connections that is in part influenced by the developmental age of their peers. In a recent study by Hankinson et al., (10) younger elementary school aged children were more likely to be uncomfortable around those with AA and afraid to get to know them. These children feared that those with AA were contagious or dying. (10) Too young to understand the situation or the disease, young unaffected children may be less inclined to interact with children with AA. Perhaps from this isolation, patients and families affected by AA seek peer support through other avenues like the Bowling Social and support group events.

The social ramifications of AA do not appear limited to the patient, but affect family members as well. Alfani et al. (11) demonstrated that issues in family relationships are more likely in families affected by AA than in those without an affected family member. The psychosocial strain of the disease may transcend the diagnosed individuals, resulting in additional stress in the larger family structure. To adequately cope, additional support from family members may be an important component. Of those at the Bowling Social, 42.2% indicated they attended in support of a friend or family member. Data from this study support that coping with alopecia could be a family affair.

Limitations

This study was limited by its cross-sectional design making causal relationships unattainable, and did not address the longitudinal impact of group interaction. Survey responses were obtained second-hand from parents of children with AA and not directly from the children themselves; therefore, parents’ perception of the benefits of group interaction may differ from the children’s perception. Population size was also low (n = 26). Additionally, the same family may have participated in the survey during both years, and due to issues of confidentiality, this information was not recorded. Lastly, participants were from the greater Minneapolis, Minnesota area and included those who enjoy support group events and were more likely to attend. Thus, results may not represent the general population affected by AA.

Conclusion

Socializing with others sharing a diagnosis of AA was unanimously identified as important. For patients and families affected by AA, most attended the support group event to meet others with AA. Future studies assessing the effect of group therapeutic support and social media on quality of life will be important in elucidating the psychological impact of these interactions for pediatric AA patients, parents of affected children and other family members.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: University of Minnesota Professional Student Government Grant, University of Minnesota Student Union Association Grants, University of Minnesota Medical School Student Group Funds.

We would like to extended special thanks to the following for their efforts in this project: Jamie Hanson, Solveig Hagen, Katherine Grey, Heather Bemmels, the University of Minnesota Dermatology Interest Group and the National Alopecia Areata Foundation.

This project was supported in part by grants from the University of Minnesota Professional Student Government, University of Minnesota Student Union Association, and University of Minnesota Medical School Student Group Funds.

Footnotes

All authors consent to publication of this work. All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

This study was exempt from the University of Minnesota IRB review. We abided by the principles in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Disclaimer: This project was supported in part by Award Number UL1TR000114 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Minnesota.

References

- 1.Hunt N, McHale S. The psychological impact of alopecia. BMJ. 2005;331(7522):951–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7522.951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tucker P. Bald is beautiful?: the psychosocial impact of alopecia areata. J Health Psychol. 2009;14(1):142–51. doi: 10.1177/1359105308097954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuty-Pachecka M. Psychological and psychopathological factors in alopecia areata. Psychiatr Pol. 2015;49(5):955–64. doi: 10.12740/PP/39064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Hollanda TR, Sodre CT, Brasil MA, et al. Quality of life in alopecia areata: a case-control study. Int J Trichology. 2014;6(1):8–12. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.136748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spano F, Donovan JC. Alopecia areata: Part 2: treatment. Can Fam Physician. 2015;61(9):757–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruiz-Doblado S, Carrizosa A, Garcia-Hernandez MJ. Alopecia areata: psychiatric comorbidity and adjustment to illness. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42(6):434–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goh C, Lane AT, Bruckner AL. Support groups for children and their families in pediatric dermatology. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24(3):302–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bilgic O, Bilgic A, Bahali K, et al. Psychiatric symptomatology and health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with alopecia areata. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(11):1463–8. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hankinson A, McMillan H, Miller J. Attitudes and perceptions of school-aged children toward alopecia areata. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(7):877–9. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alfani S, Antinone V, Mozzetta A, et al. Psychological status of patients with alopecia areata. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92(3):304–6. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]