Abstract

Diabetes Mellitus, characterized by persistent hyperglycaemia, is a heterogeneous group of disorders of multiple aetiologies. It affects the human body at multiple organ levels thus making it difficult to follow a particular line of the treatment protocol and requires a multimodal approach. The increasing medical burden on patients with diabetes-related complications results in an enormous economic burden, which could severely impair global economic growth in the near future. This shows that today’s healthcare system has conventionally been poorly equipped towards confronting the mounting impact of diabetes on a global scale and demands an urgent need for newer and better options. The overall challenge of this field of diabetes treatment is to identify the individualized factors that can lead to improved glycaemic control. Plants are traditionally used worldwide as remedies for diabetes healing. They synthesize a diverse array of biologically active compounds having antidiabetic properties. This review is an endeavour to document the present armamentarium of antidiabetic herbal drug discovery and developments, highlighting mechanism-based antidiabetic properties of over 300 different phytoconstituents of various chemical categories from about 100 different plants modulating different metabolic pathways such as glycolysis, Krebs cycle, gluconeogenesis, glycogen synthesis and degradation, cholesterol synthesis, carbohydrate metabolism as well as peroxisome proliferator activated receptor activation, dipeptidyl peptidase inhibition and free radical scavenging action. The aim is to provide a rich reservoir of pharmacologically established antidiabetic phytoconstituents with specific references to the novel, cost-effective interventions, which might be of relevance to other low-income and middle-income countries of the world.

Keywords: antidiabetics, diabetes mellitus, hyperglycaemia, metabolism, phytoconstituents

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is the most common endocrine disorder resulting from a defect in insulin secretion, insulin resistance or both. It is the third leading cause of morbidity and mortality, after heart attack and cancer. In 2015, about 415 million people had diabetes in the world and 78 million people in the Southeast Asia (SEA) region; by 2040 this will rise to 140 million. India is one of the epicentres of the global DM pandemic. There were 69.1 million cases of diabetes in India in 2015.1,2 DM characterized by persistent hyperglycaemia is a heterogeneous group of disorders of multiple aetiologies that affect the human body at multiple organ levels, thus making it difficult to follow a particular line of treatment. The treatment protocol requires a multimodal approach which should be personalized so that it varies from person to person.3 In general, DM is classified into two categories: type 1 and type 2. In type 1 diabetes (T1DM), hormone insulin is not produced due to the destruction of pancreatic β cells, while type 2 diabetes (T2DM) is characterized by a progressive impairment of insulin secretion by pancreatic β cells and by a relative decreased sensitivity of target tissues to the action of this hormone. T2DM leads to other pathological consequences like cardiovascular disorders, nephropathy, neuropathies and the patient becomes prone to a number of infections too.4 The increasing medical burden on patients with diabetes-related complications also results in an enormous economic burden, which could severely impair global economic growth in the near future. This shows that today’s health system has conventionally been poorly equipped to confront the mounting impact of diabetes on a global scale and demands an urgent need for newer and better options. The overall challenge of this field of diabetic treatment is to identify the individualized factors that can lead to improved glycaemic control.

Besides conventional oral and injectable medications, diabetes treatments include diet modification, regular exercising, lifestyle changes, weight regulation and other alternatives or add on therapies such as herbal therapy.5,6 Herbal drugs are prescribed widely as drugs of choice because of their effectiveness, few side effects and relatively low cost.7

In present day modern science, concoctions or crude extract based studies are losing their significance and the focus has, for the better, shifted towards discovery and exploitation of specific compounds for their therapeutic actions. Knowledge about specific compounds from various herbal (plant) parts makes the experimental studies easier and helps to focus on better understanding the mechanism of action and future therapeutic potential. Since diabetes is a multifaceted disease with an effect on almost all the organs,4 exploitation of plant resources for better therapeutic molecules needs a boost in research and development. Another advantage of exploiting plant-based resources is the time and money saving since it will surpass the need for drug design and screening. This review documents the present armamentarium of antidiabetic herbal drug discovery and developments, highlighting the mechanism-based antidiabetic properties of over 300 different phytoconstituents of various chemical categories from about 100 different plants modulating different metabolic pathways. The aim is to provide a rich reservoir of pharmacologically established antidiabetic phytoconstituents with specific references to the novel, cost-effective interventions, which might be of relevance to other low-income and middle-income countries of the world.

Materials and methods

This review article is a compilation of the current knowledge and future expectation of various chemical categories of phytoconstituents with their mode of actions on a single platform, which have been shown to display potent hypoglycaemic activity against DM. We have searched the literature using PubMed, SCOPUS, MEDLINE, and Google scholar with the key words ‘diabetes, antidiabetic phytoconstituents, metabolism, their mode of action on metabolic pathways, and induction’ to prepare this review article. The literature search included only articles written in the English language. The references lists of all listed articles were searched manually to obtain relevant and additional information. Review and original research articles published between 1984 and 2017 (in English) were included in this review as a reference. The selection of phytoconstituents in this review was on the basis of their antidiabetic activity and ethanopharmacological use.

Carbohydrate metabolism: problem statement

Metabolism in the living system is concerned with managing the material and energy resources within cells involving complex molecules like carbohydrates, lipids and proteins as chief substrates. After a normal meal, the transient increase in plasma glucose, amino acids, triglycerols and chylomicrons is responded to by increased secretion of insulin from pancreatic islet cells, thus enhancing the synthesis of triacylglycerols, glycogen and protein. During this period virtually all tissues use glucose as a fuel.8 Problems with glucose and carbohydrate metabolism are quite rare in cultures adhering to a primitive diet, one low in refined foods, starches and sugars. Although hereditary predispositions, viral and bacterial afflictions of the pancreas and autoantibodies to pancreatic islets do contribute to the development of this disorder, diet, lifestyle and obesity are by far the most significant risk factors.9 In the following section various pathways in which glucose is involved, either as a substrate or liberated as a product, are discussed and the corresponding plant-derived drugs that inhibit or activate the steps in these pathways are listed.

Therapy and management of DM

A combination of side effects, contraindications and lack of effect of synthetic drugs on disease progression highlight the need for newer therapies that minimize the frequency and severity of DM exacerbations.10 The plant kingdom historically has been the driving force for the development of novel drugs. Herbal products have been thought to be inherently safe because of their natural origin and traditional use rather than systemic studies designed to detect adverse effects. Approximately 80% of the world’s population relies on biomedicines for their health and wellbeing.11,12 According to ethnobotanical information based on Indian Pharmacopoeia, about 1200 plants with antidiabetic properties have been cited. Of these, around 400 plants and their products have been documented to have antidiabetic properties after significant investigation.13 There are unique theories for concepts of aetiology, systems of diagnosis and treatment for plant-derived drugs, which are vital to using them in practice. The mechanisms of action of plant-derived drugs involve regulating glycaemic metabolism, decreasing cholesterol levels, eliminating free radicals, increasing secretion of insulin and improving microcirculation.14 With the background that phytoconstituents form the mainstay of therapy and management of DM, this paper reviews the common Indian antidiabetic plants and their constituents.

Phytoconstituents and their antidiabetic effects

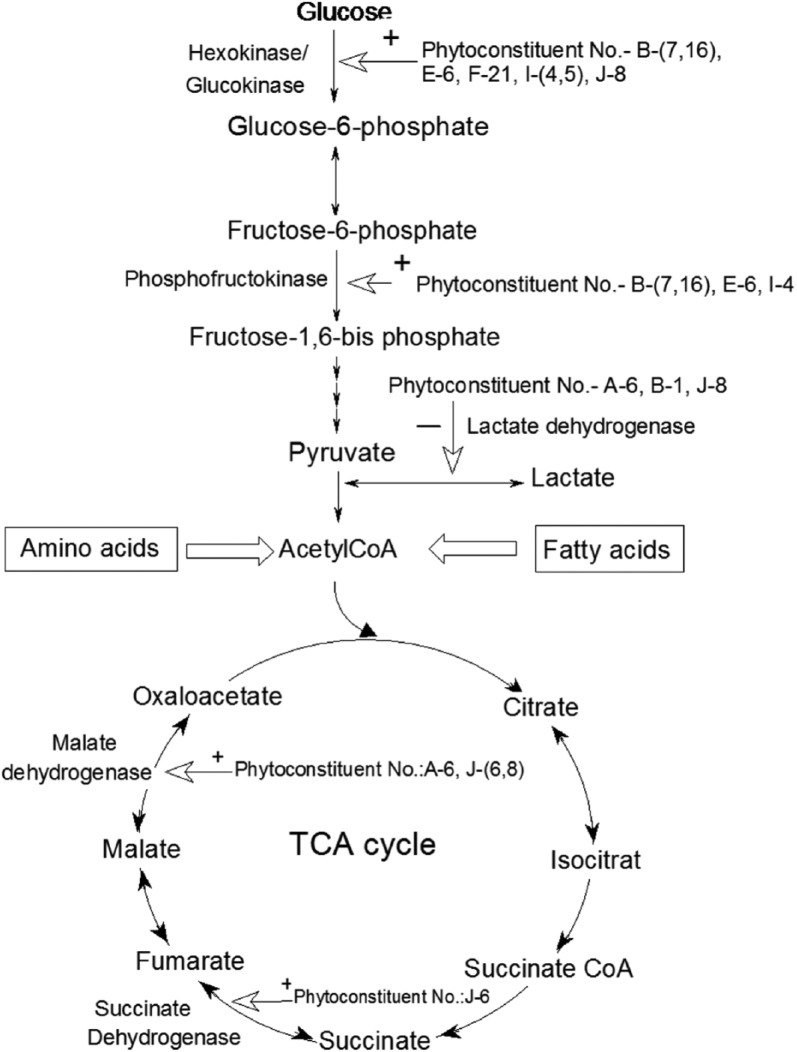

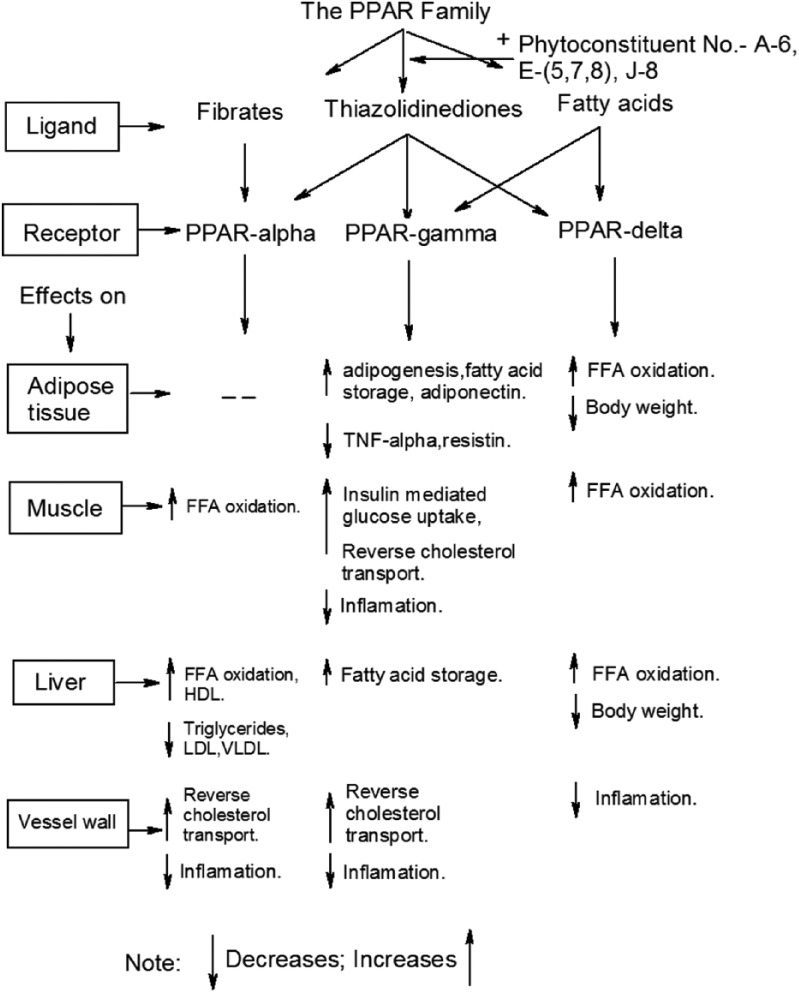

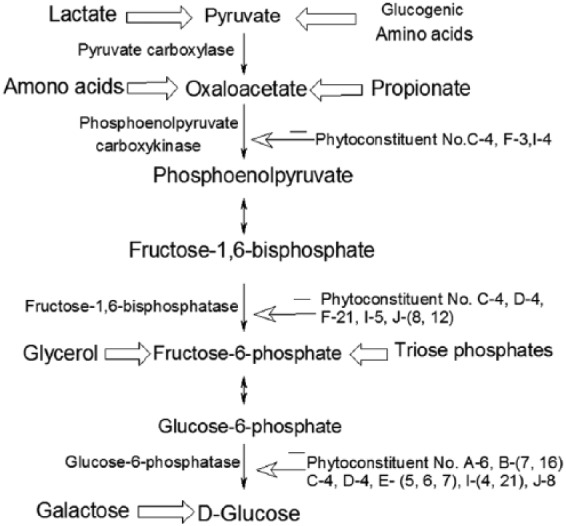

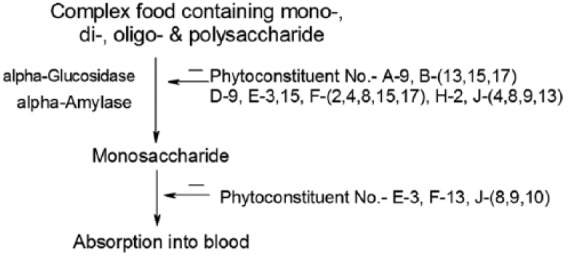

Plants contain numerous chemical compounds having medicinal values and include alkaloids, amino acids, amines and carboxylic acid derivatives, anthranoids, carbohydrates, glycosides, flavanoids, minerals, vitamins and inorganic compounds, peptidoglycans, polyphenol and its derivatives, saponins, and so on.15 These compounds are extracted from different parts of the various plants (root, stem, leaf, flower, fruit, etc.) (Table 1). This review aims to document and summarize the present knowledge about the mechanism-based action of antidiabetic plants, with emphasis on their phytoconstituents that target the various metabolic pathways in humans. The review has been organized according to various categories of phytoconstituents, targeted metabolic pathways and plant sources in Table 1 (A–J), which are also shown in Figures 1–4 at different steps with arrows and phytoconstituent numbers (A-1, B-6, J-2, etc.). Figures 1–4 clearly show the action of various phytoconstituents discussed in this review (Table 1) at different steps of various metabolic pathways.

Table 1.

Chemical categorization of various phytoconstituents having hypoglycaemic potential that regulate intermediates of different metabolic pathways.

| Sl. No. | Phytoconstituents | Targeted metabolic pathways | Plant source | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Alkaloids | |||

| 1 | Barberin | Glucose transport, carbohydrate digestion and absorption, DPP-IV inhibition | Tinospora cordifollia, Barberisaristata | Singh et al.,16 Al masri et al.17 |

| 2 | Catharanthine, vindoline, vindolinene vinblastine, vincristine | Free radical scavenging action | Cathanthrus roseus, Vinca rosea | Chattopadhyay,18 Jarald et al.,19 Kar et al.20 |

| 3 | Sotolon [4,5-dimethyl-3-hydroxy-2(5H)-furanone], trigonelline, gentianine, carpaine compounds | Glucose transport, carbohydrate digestion and absorption | Trigonella foenum graecum | Hui et al.,6 Khosla et al.21 |

| 4 | Ginkgolides | Insulin secretion | Ginkgo biloba | Pinto et al.,22 |

| 5 | Allylpropyl disulfide | Glycogen synthesis, insulin secretion | Allium sativum | Sheela et al.,23 Kumari and Augusti24 |

| 6 | Aegelin, marmesin, marmelosin | Regeneration of pancreatic β cells and insulin secretion | Aegle marmelos | Kamalakkannan and Prince,25 Ponnachan et al.26 |

| 7 | Harmine, pinoline | Insulin secretion and β-cell regeneration | Tribulus terrestris | Cooper et al.,27 Kirtikar and Basu28 |

| 8 | Betaine, achyranthine, β-ecdysone | Carbohydrate digestion and absorption | Achyranthus aspera | Akhtar and Iqbal29 |

| 9 | Castanospermine, epifagomine, fagomine | Carbohydrate digestion and absorption, insulin secretion | Xanthocercis zambesiaca | Akhtar30 |

| 10 | Castanospermine, australine | DPP-IV inhibition | Castanospermum australe | Bharti et al.,11 Orwa et al.31 |

| B | Amino acids, amines and carboxylic acid derivatives | |||

| 1 | Allicin, apigenin, alliin | Cholesterol synthesis, glycogen synthesis | Allium sativum | Gholap and Kar,32 Kumar and Reddy33 |

| 2 | Gurmarin, betaine, choline, trimethylamine | Regeneration of pancreatic β cells and insulin secretion | Gymnema sylvestre | Sugihara et al.,34 Preuss et al.35 |

| 3 | (–) Hydroxycitric acid | Insulin secretion | Garcinia cambogia, Gymnema sylvestre | Preuss et al.,35 Hayamizu et al.36 |

| 5 | Ferulic acid | Free radical scavenging activity, insulin secretion | Curcuma longa | Ohnishi et al.37 |

| 6 | Leucine, isoleucine, alanin | Insulin secretion | Aloe vera | Ajabnoor38 |

| 7 | Mallic acid, chlorogenic acid | Krebs cycle | Caralluma edulis, Syzygium cumini, Acacia Arabica | Wadood and Shah39 |

| 8 | 4-Hydroxyisoleucine, n-hydroxyisoleucine | Glucose transport, carbohydrate metabolism | Trigonella foenum graecum | Hui et al.,6 Khosla et al.21 |

| 9 | Polypeptide-P | Insulin secretion, glycogen synthesis | Momordica charantia | Chao and Huang,40 Sarkar et al.41 |

| 10 | S-methyl cysteine sulfoxide, S-allyl cysteine sulfoxide | Glycolysis, cholesterol synthesis | Alium sepa | Kumari and Augusti,24 Roman-Ramos et al.42 |

| 11 | Nitrosamines | Carbohydrate digestion and absorption | Areca catechu | Mannan et al.43 |

| 12 | Brevifolin carboxylic acid, ethyl brevifolin carboxylate | Carbohydrate digestion and absorption | Phyllanthus amarus | Ali et al.44 |

| 13 | Lectins, mistletoe lectin I, II, III, viscotoxin B, cycliton | Insulin secretion, glycogen synthesis | Viscum album | Adaramoye et al.,45 Eno et al.,46 Gray and Flatt47 |

| 14 | Furfural, caprylic acid | Insulin secretion, glycogen synthesis | Agaricus campestris | Manohar et al.,48 Gray and Flatt49 |

| 15 | Procyanidins | Antihyperglycaemic | Grape seed | Pinent et al.50 |

| 16 | Bis (2-ethyl hexyl) phthalate (DEHP) | Insulin secretion, glycogen synthesis | Cassia auriculata | Abesundara et al.51 |

| 17 | Raisin | Insulinonematic activity | Vitis vinifera | Rankin et al.52 |

| C | Anthranoids | |||

| 1 | Aloin, barbaloin, isobarbaloine, aloetic acid, aloe-emodin, emodin, cinnamic acid, crysophanic acid | Insulin secretion and synthesis | Aloe vera, Cassia tora | Ajabnoor38 |

| 2 | Vicine | Insulin secretion | Momordica charantia | Chao and Huang,40 Sarkar et al.41 |

| 3 | Torachrysone, toralactone, rhein, alaternin | Insulin secretion | Cassia tora | Nam and Choi53 |

| 4 | Camphor, eugenol, trans-β-ocimene, geraniol, α-pinene, limonene, p-cymene, 1,8-cineole, thujone | Insulin secretion, regeneration of pancreatic β cells | Ocimum canum, Coriandrum sativum, Artemisia roxburghiana, Syzygium aromaticum | Hannan et al.,54 Hussain et al.,55 Broadhurst et al.56 |

| D | Carbohydrates | |||

| 1 | Glucomannan | Insulin secretion, carbohydrate digestion | Aloe vera | Van de Venter et al.57 |

| 2 | Caryophylline | Insulin secretion, carbohydrate digestion and absorption | Ocimum sanctum, Syzygium aromaticum | Van de Venter et al.57 |

| 3 | Protein-bound polysaccharide | Insulin secretion, carbohydrate digestion and absorption | Alpinia galangal, Aloe vera, Ocimum sanctum | Van de Venter et al.57 |

| 4 | Guar gum, pectin and pectin fibres, mucilaginous fibre | Glucose transport, carbohydrate metabolism, stabilizing agents | Trigonella foenum graecum, Citrus sinensis, Coccinia indica | Kar et al.,20 Nandini et al.58 |

| 5 | Cellulose, mannose | Carbohydrate digestion and absorption | Aloe vera | Van de Venter et al.57 |

| 6 | D-threitol, D-arabinitol, palmitic acid | Carbohydrate digestion and absorption | Hericium erinaceus | Khan et al.,59 Liang et al.60 |

| 7 | L-arabino-D-xylan, cinnzeylanin, cinnzeylanol, D-glucan | Carbohydrate digestion and absorption | Cinnamomum zeylanicum | Solomon and Blannin61 |

| 8 | Mucopolysaccharide | Carbohydrate metabolism, cholesterol synthesis | Opuntia ficus indica | Godard et al.62 |

| 9 | Inulin, laevulin | Glucose transport, carbohydrate digestion and absorption | Taraxacum officinale | Godard et al.,62 Onal et al.63 |

| 10 | Fructo-oligosaccharide | Decrease glycosuria and AGEs | Aureobasidium pullulans | Bharti et al.12 |

| E | Glycosides | |||

| 1 | Gymnemic acid, gymnemosides | Regeneration of pancreatic β cells and insulin secretion | Gymnema sylvestre | Sugihara et al.,34 Preuss et al.35 |

| 2 | Vin α-ginsenoside R3 | Insulin secretion | Panax quinquefolium | Vuksan et al.64 |

| 3 | Astragalin, scopolin, skimmin, roscoside II | Regeneration of pancreatic β cells and insulin secretion | Morus alba | Gulubova and Boiadzhiev65 |

| 4 | C-glycosides | Glucose transport, carbohydrate metabolism | Trigonella foenum graecum | Gupta et al.,66 Kluwer67 |

| 5 | Momordin, momordicine, charantin | Insulin secretion, glycogen synthesis | Momordica charantia | Chao and Huang,40 Sarkar et al.41 |

| 6 | Tinosporine, cordifolide, tinosporide, cordifole, columbin | Cholesterol synthesis, glycolysis | Tinospora cordifollia, Tinospora crispa | Hui et al.,6 Kar et al.,20 Van de Venter et al.,57 Noor and Ashcroft68 |

| 7 | Momorcharaside A and B, momorcharin A and B | Insulin secretion, glycogen synthesis | Momordica charantia | Chao and Huang,40 Sarkar et al.41 |

| 8 | Cucurbitacin B, isocucurbitacin B | Insulin secretion, glycogen synthesis | Helicteres isora | Lemus et al.69 |

| 9 | Momordin-a, luffin-a | Insulin secretion, glycogen synthesis | Luffa cylindnica | Lemus et al.69 |

| 10 | Kotalanol, salacinol | Insulin secretion, glycogen synthesis | Salacia reticulate, Salacia oblonga | Huang et al.70 |

| 11 | Arbutin, eriolin | Insulin secretion, glycogen synthesis | Arctostaphylos uvaursi | Moon et al.71 |

| 12 | Citrullol, colocynthin, elaterin, elatericin B, colosynthetin | Insulin secretion, glycogen synthesis | Cifrullus colocynthis | González-Tejero et al.,72 Ziyyat et al.73 |

| 13 | Leucocyanidin, pelarogonidin | Insulin secretion, glycogen synthesis | Ficus bengalensis | Singh et al.,74 Cherian et al.,75 Kumar et al.76 |

| 14 | Taraxacin | Insulin secretion | Taraxacum officinale | Broadhurst et al.56 |

| F | Flavanoids | |||

| 1 | Chrysin, isoquercitrin | Insulin secretion | Morus alba | Roman-Ramos et al.42 |

| 3 | Epigallocatechin-gallate, gallocatechin, epicatechin, (+) catechin, (−) epicatechin | Free radical scavenging activity, insulinonematic activity | Camellia sinensis, Punica granatum, Satureja khuzestanica, Bauhinia forficata | Hii and Howell,77 Waltner-Law et al.,78 Vessal et al.,79 Li et al.80 |

| 4 | Myrciaphenones A and B, myrciacitrins I and II | Insulin secretion | Myrcia multiflora | Chattopadhyay,18 Ngueyem et al.81 |

| 5 | α-Cephalin, myricetin-3’-glucoside, ambrettolide | Insulin secretion | Abelmoschus moschatus | Chattopadhyay,18 Ngueyem et al.81 |

| 6 | Cytrus bioflavonoids (hesperidin, naringin) | Glycogen synthesis, glycolysis, gluconeogenesis | Camellia sinensis | Jung et al.82 |

| 7 | Flavanols, flavones, flavanones | Insulin secretion | Panax notoginseng | Liu et al.,83 Vuksan et al.64 |

| 8 | Quercetin, quercetrin, apigenin, rutin, apigenin-7-O-glucoside | Insulin secretion | Urtica dioica, Bauhinia varigtla, Ginkgo biloba | Hussain et al.,55 Jellin et al.84 |

| 9 | Naringenin | Insulin secretion | Camellia sinensis | Waltner-Law et al.78 |

| 10 | Soy isoflavones (genistein, diadzein) | Lipid and glucose metabolism, PPAR activation | Glycin max, Curcuma longa | Howes et al.,85 Mezei et al.86 |

| 11 | Proanthocyanidins | Insulinonematic activity | Vitis vinifera | Gray and Flatt,49 Pinent et al.,50 Rankin et al.52 |

| 12 | α-Terpineol, hexanol | Insulin secretion | Agaricus campestris | Gray and Flatt,49 Pinent et al.,50 Rankin et al.52 |

| 13 | Kaempferitrin | Glycolysis | Bauhinia candicans, Bauhinia forficata | Lemus et al.,69 Jorge et al.87 |

| 15 | (+) Catechin, (−) epicatechin, chiorogenic acid, liquiritigenin, isoliquiritigerin | Insulinomematic activity | Phylanthus embelica, Acacia Arabica, Pterocarpus marsupium, Phylanthus embelica | Grover and Vats,7 Kar et al.,20 Wadood and Shah,39 Van de Venter et al.57 |

| 16 | Silymarin, silybin, silychristin, silidianin | HMG Co A suppression | Silybum marianum | Huseini et al.88 |

| 17 | Kaempferol, isorhamnetin | Free radical scavenging activity | Ginkgo biloba | Jellin et al.84 |

| 18 | Amarogentin, swerchirin, chirantin, gentiopicrin | Insulin secretion, glycogen synthesis | Swertia chirayita | Van de Venter et al.57 |

| 19 | Tribulusamides A and B, kaempferol-3-β-D-(6’P-coumaroyl)glucoside, kaempferol-3-glucoside | Insulin secretion, free radical scavenging activity | Tribulus terrestris | Cooper et al.,27 Kirtikar and Basu28 |

| 20 | Shamimin | Insulin secretion | Biophytum sensitivum | Puri and Baral,89 Puri et al.90 |

| 21 | Leucopelargonidin, dulcitol | Insulin secretion | Casearia esculenta | Prakasam et al.91 |

| 22 | Matteuorien, matteuorienin matteuorienate A, B, C | Insulin secretion | Matteuccia orientalis | Shane-McWhorter92 |

| G | Minerals, vitamins and inorganic compounds | |||

| 1 | Zinc | Insulin secretion | Aloe vera | Wijesekara et al.,93 |

| 3 | Vitamin A,E | Free radical scavenging activity | Cucurbita pepo | Bharti et al.12 |

| H | Peptidoglycans | |||

| 1 | Fenugreekine | Glucose transport, carbohydrate digestion and absorption | Trigonella foenum graecum | Khosla et al.21 |

| 2 | Gluten, taraxacerin | Glucose transport, carbohydrate digestion and absorption | Taraxacum officinale | Hussain et al.,55 Yarnell and Abascal94 |

| 3 | Glucosamines | Insulin secretion, carbohydrate digestion and absorption | Aloe vera | Ajabnoor38 |

| I | Polyphenol and its derivatives | |||

| 1 | Curcumin, turmerone, germacrone, zingiberene | Carbohydrate digestion and absorption, insulin secretion | Curcuma longa | Kar et al.,20 Zhang et al.95 |

| 2 | Ellagic acid and its derivatives | Carbohydrate digestion and absorption, insulin secretion | Potentilla candican, Phyllanthus niruri, Caesalpinia ferrea, Arctostaphylos uvaursi | Ueda et al.96 |

| 3 | Ellagic acid, corosolic acid, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, 3-O-methylprotocatechuic acid, caffeic acid, p-coumaric acid, kaempferol | Carbohydrate digestion and absorption, insulin secretion | Lagerstroemia speciosa, Acacia Arabica | Naisheng et al.97 |

| 4 | Tannins, gallotannic acid | Regeneration of pancreatic β cells and insulin secretion | Syzygium aromaticum | Hannan et al.54 |

| 5 | Wedelolactone, dimethyl wedelolactone | Insulin secretion, carbohydrate digestion and absorption | Eclipta alba | Ananthi et al.98 |

| 6 | Carvacrol, linalool | Insulin secretion, carbohydrate digestion and absorption | Ocimum sanctum | Hannan et al.,54 Broadhurst et al.56 |

| 7 | Mangiferin | α-Glucosidase-inhibiting activity | Salacia | Yoshikawa et al.99 |

| J | Saponins | |||

| 1 | Stigmasterol, quercitol, gymnenic acid IV | Regeneration of pancreatic β cells, insulin secretion | Gymnema sylvestre | Sugihara et al.,34 Preuss et al.35 |

| 2 | Quinquenoside L3 and L9 | Regeneration of pancreatic β cells and insulin secretion | Panax quinquefolium | Vuksan et al.64 |

| 3 | Andrographolide | Regeneration of pancreatic β cells, insulin secretion | Andrographis paniculata | Yu et al.100 |

| 4 | 3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | Regeneration of pancreatic β cells and insulin secretion | Myrtus communis | Alipour et al.101 |

| 5 | 3-Hepatadecanone, 8-hexadecenoic acid hexadecenoic acid | Regeneration of pancreatic β cells and insulin secretion | Asparagus adscendens | Mathews et al.102 |

| 6 | Ginsenosides Rg2, panaxan A, B, C, D, E | Regeneration of pancreatic β cells, free radical scavenging | Panax ginseng | Ma et al.,103 Attele et al.104 |

| 7 | Lactucain C | Regeneration of pancreatic β cells, insulin secretion | Lactuca indica | Hou et al.105 |

| 9 | e-Glucoside, mangiferin, salacinol, kotalanol, epigallocatechin | Regeneration of pancreatic β cells, insulin secretion | Salacia reticulate, Salacia oblonga | Krishnakumar et al.106 |

| 10 | Allo-aromadendrene, T-cadinol, α-gurjunene, β-eudesmol, β-ubebene, aromadendrene | Regeneration of pancreatic β cells and insulin secretion | Artemisia pallens | Ruikar et al.107 |

| 11 | Diosgenin | Glucose transport, carbohydrate metabolism | Trigonella foenum graecum | Khosla et al.21 |

| 12 | Sotolon [3.hydroxy-4,5-dimethyl-2(5H)-furanone], Trigonellin | Regeneration of pancreatic β cells, insulin secretion | Trigonella foenum-graecum | Khosla et al.21 |

| 13 | Ursolic acid, mulberrofuran-U | Regeneration of pancreatic β cells and insulin secretion | Morus insignis, Myrtus communis | Basnet et al.108 |

| 14 | Kotalagenin-16-acetate, diterpene, triterpens | Carbohydrate digestion and absorption | Salacia oblongaq, Croton cajucara | Krishnakumar et al.,106 Silva et al.109 |

| 15 | Muinol, azorellanol, mulin-11,3-dien-20-oic-acid, mulinolic acid | Regeneration of pancreatic β cells and insulin secretion | Azorella compacta | Borquez et al.,110 Fuentes et al.111 |

PPAR, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor.

Figure 1.

Phytoconstituent regulation of glycolysis and Krebs cycle with sources and fate of acetyl coenzyme A.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the gluconeogenesis pathway with major substrate precursors and regulation by phytoconstituents.

Figure 3.

Regulation of carbohydrate metabolism by phytoconstituents.

Figure 4.

Mechanism of action of the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR) family and their regulation by phytoconstituents.

The PPARs are ligand-activated nuclear receptors (α, δ and γ isoforms of PPAR) that can be activated by a range of fatty acids and derivatives, and they function as regulators in the biosynthesis, metabolism and storage of fats. PPAR ligands have displayed the importance of these receptors in the regulation of lipid and glucose homeostasis.

Alkaloids

A large number of alkaloids have been isolated from numerous medicinal plants and investigated by the researchers for their possible antidiabetic activity.112 Glycolysis is the hub of carbohydrate metabolism because virtually all sugars (whether arising from the diet or from catabolic reactions in the body) ultimately can be converted to glucose via a series of 10 reactions with three regulatory steps catalysed by the enzymes hexokinase, phosphofructokinase and pyruvate kinase. The alkaloid berberine, extracted from Tinospora cordifolia, enhances the activity of hexokinase and phosphofructokinase, resulting in glucose transport, carbohydrate digestion and absorption.16

Carbohydrates are the major constituents of the normal diet of humans. Starch and sucrose are its major forms, which supply about 70–80% of the energy requirement to the body. Their digestion starts in the mouth and continues even in the small intestine producing glucose, which is absorbed into the bloodstream through the walls of the intestine, and finally it is transported to different parts of the body through the liver. The digested products are mainly glucose with small amounts of fructose and galactose. Starch is first decomposed into oligosaccharides by the enzyme α-amylase, found in saliva and pancreatic juices. A membrane-bound enzyme α-glucosidase, in the epithelium of the small intestine, catalyses the cleavage of glucose from disaccharides and oligosaccharides. Hence, α-glucosidase inhibition is one of the effective treatments for diabetes since it will delay the time of absorption of glucose.3 There are a number of phytoconstituents known to suppress the activity of α-glucosidase and inhibit the absorption of glucose in both the small intestine and kidney, so that the concentration of glucose in the blood remains constant after a meal. The α-glucosidase inhibitors slow the digestion of starch in the small intestine, so that glucose enters the bloodstream more slowly and can be matched to an impaired insulin response or production. Gluconeogenesis is a ubiquitous multistep process occurring in the liver and kidney in which pyruvate or a related three-carbon compound like lactate, alanine, is converted to glucose. Seven of the 10 enzymatic reactions of gluconeogenesis are the reverse of glycolysis with four regulatory steps that are catalysed by the enzymes pyruvate carboxylase, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase and glucose-6-phosphatase. During gluconeogenesis a phytoconstituent barberine reduces the activity of glucose-6-phosphatase enzyme which affects the conversion of d-glucose from glucose-6-phosphate.

Catharanthine, vindoline and vindolinine, obtained from Catharanthus roseus lower the blood sugar level and show free radical scavenging action.18,19 Glucose takes part in the glycation of the membrane lipid and its peroxidation to produce free radicals. In DM, the glucose concentration is very high and so is the amount of free radicals in the body which are highly reactive. To prevent their deleterious effect, our body has a defence system comprising several enzymes, which include superoxide dispiutase, catalase, reduced glutathione and glutathione-S-transferases.113 Catharanthine, vindoline and vindolinine activate these free radical scavenging enzymes and prevent our body from their adverse effects. Vinblastine and vincristine are isolated from Vinca rosea, which also activate free radical scavenging enzymes.20,57 Sotolon [4,5-dimethyl-3-hydroxy-2(5H)-furanone], trigonelline, gentianine and carpaine compounds are extracted from Trigonella foenum graecum and downregulate the activity of fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase and check the dephosphorylation of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate.21,66,67,84 Ginkgolides found in the Ginkgo biloba plant have been reported to have an antihyperglycaemic effect on in vitro models.22 The mangiferin, a xanthone glucoside found in the leaves of Mangifera indica, has antidiabetic and antihyperlipidaemic properties.114 The Allium sativum plant is a rich source of alkaloid allylpropyl disulfide that is involved in glycogen synthesis and insulin secretion.23 Glycogen synthesis is a multistep process, but allylpropyl disulfide checks the conversion of pyruvate into lactate by reducing the activity of the lactate dehydrogenase enzyme.

Aegelin, marmesin and marmelosin are the major alkaloids from the plant Aegle marmelos25,26 that causes regeneration of pancreatic β cells and insulin secretion. Insulin produced by the pancreatic β cells is one of the most important peptide hormones coordinating the utilization of fuels by tissues whose metabolic effects are anabolic, favoring, for example, the synthesis of glycogen, triacylglycerols and protein. The aim of this holistic approach by these botanicals is to repair pancreatic β cells and maintain the proper amount of insulin by increasing the expression of the insulin gene, increasing the secretion of insulin and inhibiting their degradation. Patients with T1DM have virtually no functional β cells (implicated due to genetic, autoimmune, environmental or viral factors) which leads to gradual depletion of the cellular population. They can neither respond to variations in circulating fuels nor maintain a basal secretion of insulin. Patients with T1DM must rely on exogenous insulin to control hyperglycaemia and ketoacidosis. The β carbolines (harmine, nor-harmine, pinoline) are believed to promote insulin secretion by β-cell regeneration and are the extracts of Tribulus terrestris.27,28 Carbohydrate digestion and absorption is affected by betaine, achyranthine and β ecdysone isolated from Achyranthes aspera.29 Castanospermine, epifagomine and fagomine are the chief phytoconstituents of Xanthocercis zambesiaca that are actively involved in carbohydrate digestion, absorption and insulin secretion.30 Berberine, found in the plant Berberis aristata, has been shown to have dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV)-inhibiting activity.17 The seed extract of Castanospermum australe contains three alkaloids, namely castanospermine, 7-deoxy-6-epi-castanospermine and australine, which have been shown to have DPP-IV inhibition activity and are effective in controlling the hyperglycaemic state in experimental rats.11,31

Amino acids, amines and carboxylic acid derivatives

The compounds allicin, apigenin and alliin extracted from Allium sativum target cholesterol and glycogen synthesis pathways.32,33 Cholesterol is the most abundant sterol in our body and is essential for normal functioning of the cells. If the cholesterol level exceeds the normal value, the chances of cardiovascular diseases increase. Cholesterol synthesis is approximately a 30-step process with acetyl coenzyme A (CoA) as its precursor. Regeneration of pancreatic β cells and insulin secretion are activated by gurmarin, betaine, choline, gymnemic acid IV and trimethylamine isolated from Gymnema sylvestre.32,34,35 (–) Hydroxycitric acid and 2-heptyl acetate, 2-methyl butyl acetate and isoamyl acetate are carboxylic acid derivatives from Garcinia cambogi and Gymnema sylvestre respectively that induce insulin secretion.35,36 Erulic acid from Curcuma longa activates free radical scavenging activity and insulin secretion.37 Aloe vera extracts contain leucine, isoleucin and alanine, which trigger insulin secretion.38

Some plant extracts of Caralluma edulis, Syzygium cumini and Acacia Arabica contain malic acid and chiorogenic acid that check the steps of Krebs cycle.39 The Krebs cycle is the central pathway for energy production in the mitochondrial matrix. Here pyruvate gets oxidized to CO2 and H2O via acetyl CoA with the synthesis of energy equivalent Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (NADH), which ultimately is oxidized to produce energy via the electron transport chain. Out of seven enzymes involved in the cycle, only two, succinate dehydrogenase and malate synthase, are regulated by these botanicals. The compound polypeptide-P in Momordica charantia extract is shown to regulate insulin secretion and glycogen synthesis.40,41 The compounds S-methyl cysteine sulfoxide and S-allyl cysteine sulfoxide derived from Allium cepa act on glycolysis and cholesterol synthesis.24,42 Contrarily, the nitrosamines, nitrosated derivatives found in Areca catechu, are a great hyperglycaemia risk factor in the Asian population.43 The compounds brevifolin carboxylic acid and ethyl brevifolin carboxylate extracted from Phyllanthus amarus are also involved in carbohydrate digestion and absorption.44 Viscum album extracts have been shown to have antihyperglycaemic effects and insulin-releasing effects in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats and glucose-sensitive insulin-releasing pancreatic cell lines.45–47 Coriander, a common household food ingredient used worldwide, has been shown to have significant insulin-like activity and helps in insulin secretion too.115 The compounds furfural and captylic acid from Agaricus campestris,48,49 and bis-(2-ethyl) hexyl phthalate from Cassia auriculata, enhance insulin secretion and glycogen synthesis.51 The raisins from Vitis vinifera have insulin-mimetic activity.52 Procyanidins, extracted from grape seeds, have insulin-mimetic properties.50

Anthranoids

Anthranoid compounds like aloin, barbaloin, isobarbaloine, aloetic acid, aloe-emodin, emodin, cinnamic acid and crysophanic acid from Aloe vera and Cassia tora initiate insulin secretion/synthesis.38 Momordica charantia is a rich source of vicine which acts on insulin secretion and glycogen synthesis.40,41 Extracts from Cassia tora also stimulate insulin release.53 Compounds like camphor, eugenol, trans-β-ocimene, geraniol, α-pinene, limonene, p-cymene, 1,8-cineole and thujone, which help in pancreatic β-cell restoration and insulin secretion, are reported to be found in Ocimum sanctum, Coriandrum sativum, Artemisia roxburghiana and Syzygium aromaticum.54–56

Carbohydrates

Plants like Aloe vera, Ocimum sanctum, Alpinia galangal, among others, contain polysaccharides which have a considerable hypoglycaemic effect. Glucomannan, caryophylline, protein-bound polysaccharide, cellulose and mannose from these plants are either directly or indirectly involved in insulin secretion, carbohydrate digestion and absorption.57 Guar gum, pectin and pectin fibres and mucilaginous fibre are secretory and excretory products of Trigonella foenum graecum, Citrus sinensis and Coccinia indica that initiate insulin secretion, carbohydrate digestion and absorption.20,58 Hericium erinaceus contain many β-glucan polysaccharides such as D-threitol and D-arabinitol which have antihyperglycaemic action.59,60 Carbohydrate digestion and absorption are also regulated by L-arabino-D-xylan, cinnzeylanin, cinnzeylanol and D-glucan, which are extracted from Cinnamomum zeylanicum blume.61 Opuntia ficus indica, Myrtus cummunis and Taraxacum officinale probably inhibit α-glucosidase, leading to slow absorption of carbohydrates.62,63 Fructo-oligosaccharide extract of plant and microbial origin significantly decreases glycosuria, advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and plasma triglycerides, as well as very low density lipoproteins.9

Glycosides

Gymnemic acid and gymnemosides from Gymnema sylvestre,34,35 and astragalin, scopolin, skimmin and roscoside II from Morus alba65 are mainly involved in the restoration of pancreatic β cells and insulin secretion. Some major glycosides that control the process of insulin secretion and glycogen synthesis are vin α-ginsenoside R3 from Panax quinquefolium,64 momordin, momordicine, charantin, momorcharaside A and B, and momorcharin A and B from Momordica charantia,40,41 cucurbitacin B and isocucurbitacin B from Helicteres isora,69 momordina and luffina from Luffa cylindnica,69 kotalanol and salacinol from Salacia reticulate and Salacia oblonga,70 arbutin and eriolin from Arctostaphylos uvaursi,71 citrullol, colocynthin, elaterin, elatericin B and colosynthetin from Cifrullus colocynthis,72,73 leucopelargonidin, leucocyanidin and pelarogonidin from Ficus bengalensis,74–76 and taraxacin from Taraxacum officinale.56 Tinospora cordifolli and T. crispa are the major sources of tinosporine, cordifolide, tinosporide, cordifole and columbin that regulate cholesterol synthesis and glycolysis.6,20,57,68 Glucose transport and carbohydrate metabolism are the targeted pathways of C-glycosides which are extracted from the plant Trigonella foenum graecum.66,67

Flavonoids

Flavonoids are poly-hydroxy poly-phenolic compounds which have a wide ranging herbal presence. Flavonoids are classified into categories like flavanols, flavones and flavanones, and have numerous medicinal effects including antidiabetic properties. Chrysin and isoquercitrin isolated from Morus alba are involved in insulin secretion.42 Free radical scavenging and insulinonematic activity have been shown by epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), epigallocatechin (EGC), epicatechin, catechin and quercetin extracted from Camellia sinensis, Punica granatum, Satureja khuzestanica and Bauhinia forficate.77–80 Myrcia multiflora and Abelmoschus moschatus are important sources of myrciaphenones A and B, and myrciacitrins I and II.18,81 Citrus bioflavonoids (hesperidin and naringin) are extracts of Camellia sinensis which target glycogen synthesis, glycolysis and gluconeogenesis.82 Flavanoids such as quercetin, quercetrin, apigenin, rutin, apigenin-7-O-glucoside and naringenin are important phytoconstituents of Panax notoginseng,83,64 Urtica dioica, Bauhinia varigtla55,84 and Camellia sinensis78 which are actively involved in the restoration of pancreatic β-cell and insulin secretion. Soy isoflavones (genistein and diadzein) are major chemical constituents of Glycin max and Curcuma longa and are involved in lipid and glucose metabolism by activation of peroxisome proliferator activated receptors (PPARs).85,86 The PPARs bind DNA as heterodimers with the retinoid X receptors to the peroxisome proliferator response elements identified in the promoter region of a number of genes involved in lipid and carbohydrate metabolism.11,12 The three human isoforms of PPAR, α, δ and γ, show distinct patterns of tissue distribution and ligand preference, and control different biological activities (Figure 4). PPARα is a regulator of fatty acid catabolism and peroxisome proliferation in the liver, while PPARγ plays a key role in adipogenesis. All three isoforms are expressed in macrophages where they are implicated in the control of cholesterol efflux. The use of synthetic PPAR ligands has demonstrated the importance of these receptors in the regulation of lipid and glucose homeostasis and today PPARs are established molecular targets for the treatment of T2DM and cardiovascular disease.11,12,116 Phytoconstituents like aegelin, marmesin, marmelosin, momordin, momordicine, charantin, momorcharaside A and B, momorcharin A and B, cucurbitacin B, isocucurbitacin B and β-sitosterol (Table 1) increase the expression of PPARγ and decrease insulin resistance. The thiazolidinediones class of drugs (troglitazone, pioglitazone, etc.) is known to consist of activators of PPARγ, which are used pharmacologically as insulin sensitizers. With the growing understanding of PPAR biology, it has become evident that novel herbal drugs modulating PPAR activity could improve current diabetes treatment.11,12,116

Bauhinia candicans and Bauhinia forficata produce kaempferitrin that affects glycolysis.69,87 Proanthocyanidins, α-terpineol and hexanol obtained from Vitis vinifera and Agaricus campestris have insulinomimetic activity.49,50,52 The compounds catechin, epicatechin, chiorogenic acid, liquiritigenin and isoliquiritigerin have been extracted from a number of plants, namely, Phylanthus embelica, Acacia Arabica, Pterocarpus marsupium and Phylanthus embelica.7,20,39,57 Insulinomimetic activity was also shown by the potential applications of silymarin, silybin, silychristin and silidianin (extracts of Silybum marianum) along with 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl Coenzyme A (HMG CoA) suppression activity.88 Insulin secretion and glycogen synthesis are also targeted by amarogentin, swerchirin, chirantin and gentiopicrin (extracts of Swertia chirayita),57 shamimin (extracts of Biophytum sensitivum),89,90 leucopelargonidin and dulcitol (extracts of Casearia esculenta),91 isorhamnetin, quercetin and kaempferol (extracts of Matteuccia orientalis) and anthocyanosides (bioflavonoids found in bilberry).92 Among all the reported flavonoids in Table 1, some have potential antidiabetic effects, like quercetin, naringenin, chrysin,20 citrus bioflavonoids like hesperidin and naringin,117 anthocyanidins,92 soy isoflavones genistein or daidzein,86 kaempferitrin [kaempferol-3,7-O-(alpha)-l-dirhamnoside],69,87 green tea flavonoid, EGCG and epicatechin.78

Minerals and vitamins

Zinc has been shown to be associated with proper functioning of pancreatic β cells and maturation of insulin secretory granules. A high serum level of zinc has been related to improved insulin sensitivity. The antioxidant property of zinc has been related to the prevention of oxidative stress.93 It has been shown that oxidative stress plays an important role in DM and reactive oxygen/nitrogen species (ROS/RNS: superoxides, hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl anions, singlet oxygen and nitric oxide) are believed to be important independent risk factors that are developed in DM and known as autooxidative glycosylation (a process which is relevant at elevated blood glucose level).118 Once they have formed, they react with cellular components such as DNA, or the cell membrane and cellular damage starts due to a chain reaction. Cells may function poorly or die if this occurs. Many phytoconstituents have antioxidant properties that inhibit the formation of free radicals and lipid peroxidation or neutralize them in cells to prevent the propagation reaction from continuing. Tocopherol and carotenoids, the two common natural vitamins, from the seeds of Cucurbita pepo (pumpkin) have been shown to have antidiabetic effects on experimental diabetic rats.12 Vitamin D has a strong relation with pathogenesis of T2DM. Vitamin D level and β-cell functioning are positively correlated. Vitamin D deficiency leads to T2DM and people with T2DM are also prone to vitamin D deficiency and related pathologies.119,120 Vitamin D supplementation improves fasting plasma glucose and insulin level.121

Peptidoglycans

A few phytoconstituents of this category like fenugreekine (extract of Trigonella foenum graecum),21 inulin, taraxacosides (extract of Taraxacum officinale)55,94 and glucosamines (extract of Aloe vera)38 are efficiently involved in glucose transport, carbohydrate digestion and absorption.

Polyphenol and its derivatives

Polyphenolic phytochemicals are ubiquitous in plants, in which they function in various protective roles. It is suggested that polyphenols, and particularly curcuminoids might be of value as a complement to pharmaceutical treatment, but also prebiotic treatment, in conditions proven to be rather therapy resistant, such as Crohn’s disease, long-stay patients in intensive care units, but also for conditions such as cancer, liver cirrhosis, chronic renal disease, chronic obstructive lung disease, diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. Curcuma longa is the chief source of curcumin, turmerone, germacrone and zingiberene which improve glucose metabolism.20,95 There are so many plants such as Potentilla candican, Phyllanthus niruri, Caesalpinia ferrea and Arctostaphylos uvaursi which produce ellagic acid, helpful in carbohydrate digestion and absorption, and insulin secretion.96 A number of phytoconstituents like corosolic acid, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, 3-O-methylprotocatechuic acid, caffeic acid, p-coumaric acid and kaempferol are actively involved in carbohydrate digestion and absorption, and insulin secretion. These phytoconstituents are extracted from Lagerstroemia speciosa and Acacia arabica.97 Compounds like wedelolactone and dimethyl wedelolactone, extracted from Eclipta alba, are involved in insulin secretion and carbohydrate digestion.98 Phytoconstituents of Ocimum sanctum (carvacrol, linalool) regulate insulin secretion, carbohydrate digestion and absorption.54,56 Mangiferin extracted from Salacia species has α-glucosidase-inhibiting activity, making it an effective antihyperglycaemic agent.99

Saponins

Saponins are bioactive compounds present naturally in many plants and known to possess potent antihyperglycaemic activity.26 Stigmasterol, quercitol, gymnenic acid IV (extract of Gymnema sylvestre),34,35 quinquenoside L3 and L9 (extract of Panax quinquefolium),64 andrographolide (extract of Andrographis paniculata),100 myrtucommulone and limonene (extract of Myrtus communis),101 3-hepatadecanone and 8-hexadecenoic acid (extract of Asparagus adscendens)102 and ginsenosides Rg2 and panaxan A, B, C, D, E (extract of Panax quinquefolium)103,104 are efficiently involved in the restoration of pancreatic β-cell and insulin secretion. Lactucain C obtained from Lactuca indica was found to produce significant antihyperglycaemic activity.105 Salacinol, kotalanol and EGC obtained from Salacia reticulate and Salacia oblonga were found to possess significant antihyperglycaemic activity.70,106 Several polyphenols obtained from the plant of Artemisia pallens exhibit potent antioxidant and hypoglycaemic activity.107,122 Diosgenin from Trigonella foenum graecum regulates glucose transport and carbohydrate metabolism but the exact action mechanism of the constituents is not properly understood.21 Sotolon [3-hydroxy-4,5-dimethyl-2(5H)-furanone] and trigonellin are other compounds of Trigonella foenum graecum which restore pancreatic β cells for proper insulin secretion.21 Ursolic acid and mulberrofuran-U of Morus insignis have antihyperglycaemic activity in both types of diabetes.108 Kotalagenin-16-acetate, diterpene and triterpens are a few saponins extracted from the plants Salacia oblongaq and Croton cajucara.106,109 They are either directly or indirectly involved in carbohydrate digestion and absorption. Extract of Azorella compacta contains muinol, azorellanol, mulin-11, 3-dien-20-oic-acid and mulinolic acid,110,111 which restore pancreatic β cells and increase insulin secretion.

Conclusion

Diabetes is a disorder of carbohydrate, fat and protein metabolism attributed to the diminished production of insulin or mounting resistance to its action. In spite of all the advances in therapeutics, diabetes still remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the world. The most commonly used drugs of modern medicine such as aspirin, antimalarials, anticancers, digitalis, among others, originated from plant sources. Considering the safety, efficacy and time tested utility in humans under different traditional systems of medicines, plant sources are regarded as safe. Thus, plants offer a natural alternative or an adjunct to conventional agents with fewer side effects. However, for concrete evidence and application as drugs in the stricter norms of drug development, more studies are required to evaluate their activities and associated benefits in the prevention or treatment of diabetes in humans. Several plant-derived drugs have been scientifically validated as potent antidiabetics and include flavonoids (queretin, neringerin and chrysin), alkaloids (berberin, catharenthine and vindolin), glycosides and saponins (triterpenoid and steroidal glycosides such as charantin, lactucain C, β-sitosterol and gymnemic acid), glycolipids, dietary fibres, imidazole compounds, polysaccharides, peptidoglycans, carbohydrates and amino acids. Among these, the alkaloids, flavonoids and saponins show diverse effects. Most of the plants having antihyperglycaemic activity also show other functions that are beneficial to patients with DM. Taken together, the data on botanical compounds compiled in this review provide a lead with respect to diabetes management, showing the regulatory effects on various steps of different metabolic pathways that may have therapeutic and other applications. Although recent progress has been made in understanding the underlying mechanisms and diverse activities of these plant-derived drugs, further studies are required to firmly establish the mechanisms of actions.

Future prospects

Using biotechnological tools, the future would be better equipped to offer personalized approaches to preventive diabetology. Advances in plant genomics would facilitate individualized diets customized to a person’s genetic profile to maximize health and wellbeing. A futuristic doctor’s desk reference would contain information on individual genetic profiles to be matched with specific phytochemical interventions. Simultaneously, toxicity to specific ingredients would be minimal, as recommendations would be based on an individual’s genetic profiles and susceptibility data. Armed with a cornucopia of phytoconstituents, and a dazzling array of genomic evidence, preventive diabetology is all set to trace the footprints of ancient wisdom. Also, these drugs are absolutely natural and very economical, which could make them applicable for the masses at large. In addition, many herbal remedies used today have not undergone careful scientific assessment and some have the potential to cause serious toxic effects and major drug–drug interactions.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Department of Biotechnology, National Institute of Technology, Raipur, India, and the Department of Biochemistry, Patna University, Patna, India for providing facilities, space and resources.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

ORCID iD: Awanish Kumar  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8735-479X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8735-479X

Contributor Information

Sudhanshu Kumar Bharti, Department of Biochemistry, Patna University, Patna, Bihar, India.

Supriya Krishnan, Department of PMIR, Patna University, Patna, Bihar, India.

Ashwini Kumar, Department of Biotechnology, National Institute of Technology, Raipur, Chhattisgarh, India.

Awanish Kumar, Department of Biotechnology, National Institute of Technology, GE Road, Raipur, Chhattisgarh, 492010, India.

References

- 1. Unnikrishnan R, Anjana RM, Mohan V. Diabetes mellitus and its complications in India. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2016; 12: 357–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. International Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes atlas. 7th ed. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kumar A, Bharti SK, Kumar A. Therapeutic molecules against type 2 diabetes: what we have and what are we expecting? Pharmacol Rep 2017; 69: 959–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kumar A, Bharti SK, Kumar A. Type 2 diabetes mellitus: the concerned complications and target organs. Apollo Med 2014; 11: 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bharti SK, Krishnan S, Gupta AK. Herbal formulation to combat type 2 diabetes mellitus. Germany: LAMBERT Academic Publishing, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hui H, Tang G, Go VL. Hypoglycemic herbs and their action mechanisms. Chin Med 2009; 12: 4–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grover JK, Vats V. Shifting paradigm from conventional to alternate medicine: an introduction on traditional Indian medicine. Asia Pac Biotech News 2000; 5: 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ruderman MB, Tornheim K, Goodman MN. Fuel homeostasis and intermediary metabolism of carbohydrate, fat and protein. In: Becker KL, Bilezikian JP, Bremner WJ, et al. (eds) Principles and practice of endocrinology and metabolism. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 2001, pp.1257–1271. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bharti SK, Krishnan S, Kumar A, et al. Antidiabetic activity and molecular docking of fructooligosaccharides produced by Aureobasidium pullulans in poloxamer-407-induced T2DM rats. Food Chem 2013; 136: 813–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Park K. Park’s textbook of preventive and social medicine. 22th ed. Jabalpur: M/S Banarasidas Bhanot, 2013, pp.302–309. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bharti SK, Krishnan S, Kumar A, et al. Antihyperglycemic activity with DPP-IV inhibition of alkaloids from seed extract of Castanospermum australe: investigation by experimental validation and molecular docking. Phytomedicine 2012; 20: 24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bharti SK, Kumar A, Sharma NK, et al. Tocopherol from seeds of Cucurbita pepo against diabetes: validation by in vivo experiments supported by computational docking. J Formos Med Assoc 2013; 112: 676–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alarcon-Aguilara FJ, Roman-Ramos R, Perez-Gutierrez S, et al. Study of the anti-hyperglycemic effect of plants used as antidiabetics. J Ethnopharmacol 1998; 61: 101–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Luo J, Fort DM, Carlson TJ, et al. Cryptolepis sanguinolenta: an ethnobotanical approach to drug discovery and the isolation of a potentially useful new antihyperglycaemic agent. Diabet Med 1998; 15: 367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bharti SK, Krishnan S, Kumar A. Phytotherapy for diabetes mellitus: back to nature. Minerva Endocrinol 2016; 41: 143–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Singh SS, Pandey SC, Srivastava S, et al. Chemistry and medicinal properties of Tinospora cordifolia (Guduchi). Indian J Pharmacol 2003; 35: 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Al masri IM, Mohammad MK, Tahaa MO. Inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV) is one of the mechanisms explaining the hypoglycemic effect of berberine. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2009; 24: 1061–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chattopadhyay RR. A comparative evaluation of some blood sugar lowering agents of plant origin. J Ethnopharmacol 1999; 67: 367–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jarald EE, Sheeja E, Motwani S, et al. Comparative evaluation of antihyperglycaemic and hypoglycaemic activity of various parts of Catharanthus roseus Linn. Res J Med Plant 2008; 2: 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kar A, Choudhary BK, Bandyopadhyay NG. Comparative evaluation of hypoglycaemie activity of some Indian medicinal plants in alloxan diabetic rats. J Ethnopharmacol 2003; 84: 105–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Khosla P, Gupta DD, Nagpal RK. Effect of Trigonella foenum graecum (Fenugreek) on serum lipids in normal and diabetic rats. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 1995; 27: 89–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pinto MDS, Kwon YI, Apostolidis E, et al. Potential of Ginkgo biloba L. leaves in the management of hyperglycemia and hypertension using in vitro models. Bioresour Technol 2009; 100: 6599–6609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sheela CG, Kumud K, Augusti KT. Anti-diabetic effects of onion and garlic sulfoxide amino acids in rats. Planta Med 1995; 61: 356–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kumari K, Augusti KT. Lipid lowering effect of S-methyl cysteine sulfoxide from Allium cepa Linn in high cholesterol diet fed rats. J Ethnopharmacol 2007; 109: 367–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kamalakkannan N, Prince PSM. The effect of Aegle marmelos fruit extract in streptozotocin diabetes: a histopathological study. J Herb Pharmacol 2005; 5: 87–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ponnachan PT, Paulose CS, Panikkar KR. Effect of leaf extract of Aegle marmelose in diabetic rats. Indian J Exp Biol 1993; 31: 345–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cooper EJ, Hudson AL, Parker CA, et al. Effects of the beta-carbolines, harmane and pinoline, on insulin secretion from isolated human islets of Langerhans. Eur J Pharmacol 2003; 482: 189–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kirtikar KR, Basu BD. Indian medicinal plants, vol. 1 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Akhtar MS, Iqbal J. Evaluation of the hypoglycaemic effect of Achyranihes aspera in normal and alloxan-diabetic rabbits. J Ethnopharmacol 1991; 31: 49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Akhtar MS. Hypoglycaemic activities of some indigenous medicinal plants traditionally used as antidiabetic drugs. J Pak Med Assoc 1992; 42: 271–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Orwa C, Mutua A, Kindt R, et al. Agroforestree database: a tree reference and selection guide version 4.0. Kenya: World Agroforestry Centre, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gholap S, Kar A. Hypoglycaemic effects of some plant extracts are possibly mediated through inhibition in corticosteroid concentration. Pharmazie 2004; 59: 876–878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kumar GR, Reddy KP. Reduced nociceptive responses in mice with alloxan induced hyperglycemia after garlic treatment. Indian J Exp Biol 1999; 37: 662–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sugihara Y, Nojima H, Matsuda H, et al. Antihyperglycemic effects of gymnemic acid IV, a compound derived from Gymnema sylvestre leaves in streptozotocin-diabetic mice. J Asian Nat Prod Res 2000; 2: 321–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Preuss HG, Bagchi D, Bagchi M, et al. Effects of a natural extract of (-)-hydroxycitric acid (HCA-SX) and a combination of HCA-SX plus niacin-bound chromium and Gymnema sylvestre extract on weight loss. Diabetes Obes Metab 2004; 6: 171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hayamizu K. Effect of Garcinia cambogia extract on serum leptin and insulin in mice. Fitoterapia 2003; 74: 267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ohnishi M, Matuo T, Tsuno T, et al. Antioxidant activity and hypoglycemic effect of ferulic acid in STZ-induced diabetic mice and KK-Ay mice. Biofactors 2004; 21: 315–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ajabnoor MA. Effect of aloes on blood glucose levels in normal and alloxan diabetic mice. J Ethnopharmacol 1990; 28: 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wadood AN, Shah SA. Effects of Acacia arabica and Caralluma edulis on blood glucose levels of normal and alloxan diabetic rabbits. J Pak Med Assoc 1989; 39: 208–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chao CY, Huang CJ. Bitter gourd (Momordica charantia) extract activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and upregulates the expression of the acyl CoA oxidase gene in H4IIEC3 hepatoma cells. J Biomed Sci 2003; 10: 782–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sarkar S, Pranava M, Marita R. Demonstration of the hypoglycemic action of Momordica charantia in a validated animal model of diabetes. Pharmacol Res 1996; 33: l–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Roman-Ramos R, Flores-Saenz JL, Alarcon-Aguilar FL. Anti-hyperglycemic effect of some edible plants. J Ethnopharmacol 1995; 48: 25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mannan N, Boucher BJ, Evans SJW. Increased waist size and weight in relation to consumption of Areca catechu (betel-nut); a risk factor for increased glycaemia in Asians in East London. Br J Nutr 2000; 83: 267–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ali H, Houghton PJ, Soumyanath A. α-Amylase inhibitory activity of some Malaysian plants used to treat diabetes; with particular reference to Phyllanthus amarus. J Ethnopharmacol 2006; 107: 449–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Adaramoye O, Amanlou M, Habibi-Rezaei M, et al. Methanolic extract of African mistletoe (Viscum album) improves carbohydrate metabolism and hyperlipidemia in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Asian Pac J Trop Med 2012; 5: 427–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Eno AE, Ofem OE, Nku CO, et al. Stimulation of insulin secretion by Viscum album (mistletoe) leaf extract in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Afr J Med Med Sci 2008; 37: 141–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gray AM, Flatt PR. Insulin-secreting activity of the traditional antidiabetic plant Viscum album (mistletoe). J Endocrinol 1999; 160(3): 409–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Manohar V, Talpur NA, Echard BW, et al. Effects of a water-soluble extract of maitake mushroom on circulating glucose/insulin concentrations in KK mice. Diabetes Obes Metab 2002; 4: 43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gray AM, Flatt PR. Insulin-releasing and insulin-like activity of Agaricus campestris (mushroom). J Endocrinol 1998; 157: 259–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pinent M, Blay M, Blade MC, et al. Grape seed-derived procyanidins have an antihyperglycemic effect in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats and insulinomimetic activity in insulin-sensitive cell lines. Endocrinology 2004; 145: 4985–4990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Abesundara KJM, Mastui T, Matsumoto K. α-Glucoidase inhibitory activity of some Sri Lanka plant extracts, one of which, Cassia auriculata, exerts a strong antihyperglycemic effect in rats comparable to the therapeutic drug acarbose. J Agric Food Chem 2004; 52: 2541–2545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rankin JW, Andreae MC, Oliver Chen CY, et al. Effect of raisin consumption on oxidative stress and inflammation in obesity. Diabetes Obes Metab 2008; 10: 86–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nam J, Choi H. Effect of butanol fraction from Cassia tora L. seeds on glycemic control and insulin secretion in diabetic rats. Nutr Res Pract 2008; 2: 240–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hannan JM, Marcnah L, Au L, et al. Ocimum sanctum leaf extracts stimulate insulin secretion from perfused pancreas, isolated islets and clonal pancreatic β-cells. J Endocrinol 2006; 189: 127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hussain Z, Waheed A, Qurshi RA, et al. The effect of medicinal plants of Islamabad and Murree region of Pakistan on insulin secretion from INS-1 cells. Phytother Res 2004; 18: 73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Broadhurst CL, Polansky MM, Anderson RA. Insulin-like biological activity of culinary and medicinal plant aqueous extracts in-vitro. J Agric Food Chem 2000; 48: 849–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Van de, Venter M, Roux S, Bungu LC, et al. Antidiabetic screening and scoring of 11 plants traditionally used in South Africa. J Ethnopharmacol 2008; 119: 81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nandini CD, Sambaiah K, Salimath PV. Dietary fibres ameliorate decreased synthesis of heparan sulphate in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. J Nutr Biochem 2003; 14: 203–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Khan MA, Tania M, Liu R, et al. Hericium erinaceus: an edible mushroom with medicinal values. J Complement Integr Med 2013; 10(1): 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Liang B, Guo Z, Xie F, et al. Antihyperglycemic and antihyperlipidemic activities of aqueous extract of Hericium erinaceus in experimental diabetic rats. BMC Complement Altern Med 2013; 13: 253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Solomon TP, Blannin AK. Effects of short-term cinnamon ingestion on in vivo glucose tolerance. Diabetes Obes Metab 2007; 9: 895–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Godard MP, Ewing BA, Pischel I, et al. Acute blood glucose lowering effects and long-term safety of OpunDiaTM supplementation in pre-diabetic males and females. J Ethnopharmacol 2010; 130: 631–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Onal S, Timur S, Okutucu B, et al. Inhibition of alpha-glucosidase by aqueous extracts of some potent antidiabetic medicinal herbs. Prep Biochem Biotechnol 2005; 35: 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Vuksan V, Sievenpiper JL, Koo VY, et al. American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius L) reduces postprandial glycemia in nondiabetic subjects and subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160: 1009–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Gulubova R, Boiadzhiev TS. Morphological changes in the endocrine pancreas of the rabbit after the administration of a Morus alba extract. Eksp Med Morfol 1975; 14: 166–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Gupta D, Raju J, Baquer NZ. Modulation of some gluconeogenic enzyme activities in diabetic rat liver and kidney: effect of antidiabetic compounds. Indian J Exp Biol 1999; 37: 196–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kluwer WC. The review of natural products by facts and comparisons. St Louis, MO: Facts & Comparisons®, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Noor H, Ashcroft SJH. Insulinotropic activity of Tinospora crispa extract: effect on β-cell Ca2+ handling. Phytother Res 1998; 12: 98–102. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Lemus I, Garcia R, Dclvillar E, et al. Hypoglycemic activity of four plants used in Chilean popular medicine. Phytother Res 1999; 13: 91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Huang TH, He L, Qin Q, et al. Salacia oblonga root decreases cardiac hypertrophy in Zucker diabetic fatty rats: inhibition of cardiac expression of angiotensin II type 1 receptor. Diabetes Obes Metab 2008; 10: 574–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Moon YH, Nam SH, Kang J, et al. Enzymatic synthesis and characterization of arbutin glucosides using glucansucrase from Leuconostoc mesenteroides. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2007; 27: 559–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. González-Tejero MR, Casares-Porcel M, Sánchez-Rojas CP, et al. Medicinal plants in the Mediterranean area: synthesis of the results of the project Rubia. J Ethnopharmacol 2008; 116: 341–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ziyyat A, Lcgssyer A, Mekhfi HR, et al. Phytotherapy of hypertension and diabetes in oriental Morocco. J Ethnopharmacol 1997; 58: 45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Singh RK, Mehta S, Jaiswal D, et al. Antidiabetic effect of Ficus bengalensis aerial roots in experimental animals. J Ethnopharmacol 2009; 123: 110–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Cherian S, Sheela CG, Augusti KT. Insulin sparing action of leucopelergonidin derivative isolated from Ficus bengalensis Linn. Indian J Exp Biol 1995; 33: 608–611. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kumar RV, Augusti KT. Insulin sparing action of leucocyanidin derivative isolated from Ficus bengalensis Linn. Indian J Biochem Biophys 1994; 31: 73–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Hii SCT, Howell SL. Effects of epicatechin on rat islets of Langerhans. Diabetes 1984; 33: 291–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Waltner-Law ME, Wang XL, Law BK, et al. Epigallocatechin gallate: a constituent of green tea, represses hepatic glucose production. J Biol Chem 2002; 277: 34933–34940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Vessal M, Hemmati M, Vasei M. Hypoglycemic effects of quercetin in streptozocin-induced diabetic rats: comparative biochemistry and physiology. Toxicol Pharmacol 2003; 135: 357–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Li Y, Qi Y, Huang TH, et al. Pomegranate flower: a unique traditional antidiabetic medicine with dual PPAR-alpha/-gamma activator properties. Diabetes Obes Metab 2008; 10: 10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ngueyem TA, Brusotti G, Caccialanza G, et al. The genus Bridelia: a phytochemical and ethnopharmacological review. J Ethnopharmacol 2009; 124: 339–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Jung UJ, Lee MK, Jeong KS, et al. The hypoglycemic effects of hesperidin and naringin are partly mediated by hepatic glucose-regulating enzymes in C57BL/KsJ-db/db mice. J Nutr 2004; 134: 2499–2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Liu KZ, Li JB, Lu HL, et al. Effects of Asiragalus and saponins of Panax notoginseng on MMP-9 in patients with type 2 diabetic. Macroangiopathy 2004; 29: 264–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Jellin JM, Batz F, Hitchens K. Pharmacist’s letter/prescriber’s letter natural medicines comprehensive database. Stockton, CA: Therapeutic Research Faculty, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 85. Howes JB, Tran D, Brillante D, et al. Effects of dietary supplementation with isoflavones from red clover on ambulatory blood pressure and endothelial function in postmenopausal type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2003; 5: 325–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Mezei O, Banz WJ, Steger RW, et al. Soy isoflavones exert hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effects through the PPAR pathways in obese Zucker rats and murine RAW 264.7 cells. J Nutr 2003; 133: 1238–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Jorge AP, Horst H, de Sousa E, et al. Insulinomimetic effects of kaempferitrin on glycaemia and on glucose uptake in rat soleus muscle. Chem Biol Interact 2004; 149: 89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Huseini HF, Larijani B, Heshmat R, et al. The efficacy of Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn (Silymarin) in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Phytother Res 2006; 20: 1036–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Puri D, Baral N. Hypoglycemic effect of Biophytum sensitivum in the alloxan diabetic rabbits. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 1998; 42: 401–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Puri D. The insulinotropic activity of a Nepalese medicinal plant Biophytum sensitivum: preliminary experimental study. J Ethnopharmacol 2001; 78: 89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Prakasam A, Sethupathy S, Pugalendia KV. Antiperoxidative and antioxidant effects of Casearia esculenta root extract in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Yale J Biol Med 2005; 78: 15–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Shane-McWhorter L. Biological complementary therapies: a focus on botanical products in diabetes. Diabetes Spectr 2001; 14: 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- 93. Wijesekara N, Chimienti F, Wheeler MB. Zinc, a regulator of islet function and glucose homeostasis. Diabetes Obes Metab 2009; 11(Suppl. 4): 202–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Yarnell E, Abascal K. Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale and T. mongolicum). Integ Med 2009; 8: 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- 95. Zhang D, Fu M, Gao SH, et al. Curcumin and diabetes: a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013; 2013: 636053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Ueda H, Kawanishi K, Moriyasu M. Effects of ellagic acid and 2-(2,3,6-trihydroxy-4-carboxyphenyl) ellagic acid on sorbitol accumulation in vitro and in vivo. Biol Pharm Bull 2004; 27: 1384–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Naisheng B, Kan H, Roller M, et al. Active compounds from Lagerstroemia speciosa, insulin-like glucose uptake-stimulatory/inhibitory and adipocyte differentiation-inhibitory activities in 3T3-L1 cells. J Agric Food Chem 2008; 56: 11668–11674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Ananthi J, Prakasam A, Pugalendi KV. Antihyperglycemic activity of Eclipta alba leaf on alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Yale J Biol Med 2003; 76: 97–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Yoshikawa M, Nishida N, Shimoda H, et al. Polyphenol constituents from Salacia species: quantitative analysis of mangiferin with alpha-glucosidase and aldose reductase inhibitory activities. Yakugaku Zasshi 2001; 121: 371–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Yu BC, Hung CR, Chen WC, et al. Antihyperglycemic effect of andrographolide in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Planta Med 2003; 69: 1075–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Alipour G, Dashti S, Hosseinzadeh H. Review of pharmacological effects of Myrtus communis L. and its active constituents. Phytother Res 2014; 28: 1125–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Mathews JN, Flatt PR, Abdel-Wahab YH. Asparagus adseendens (Shweta musali) stimulates insulin secretion, insulin action and inhibits starch digestion. Br J Nutr 2006; 95: 576–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Ma SW, Benzie IF, Chu TT, et al. Effect of Panax ginseng supplementation on biomarkers of glucose tolerance, antioxidant status and oxidative stress in type 2 diabetic subjects: results of a placebo-controlled human intervention trial. Diabetes Obes Metab 2008; 10: 1125–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Attele AS, Zhou YP, Xie JT, et al. Antidiabetic effects of Panax ginseng. Diabetes 2002; 51: 1851–1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Hou CC, Lin SJ, Cheng JT, et al. Hypoglycemic dimeric guianolides and a lignan glycoside from Lactuca indica. J Nat Prod 2003; 66: 625–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Krishnakumar K, Augusti KT, Vijavammal PL. Hypoglycaemic and anti-oxidant activity of Salacia oblonga wall extract in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 1999; 43: 510–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Ruikar AD, Khatiwora E, Ghayal NA. Studies on aerial parts of Artemisia pallens wall for phenol, flavonoid and evaluation of antioxidant activity. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2011; 2: 302–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Basnet P, Kadota S, Terashima S. Two new 2-arylbenzofuran derivatives from hypoglycaemic activity-bearing fractions of Morus insignis. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1993; 41: 1238–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Silva RM, Santos FA, Rao VS, et al. Blood glucose and triglyceride lowering effect of trans-dehydrocrotonin, a diterpene from Croton cajucara Benth in rats. Diabetes Obes Metab 2001; 3: 452–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Borquez J, Loyola LA, Morales G, et al. Azorellane diterpenoids from Laretia acaulis inhibit nuclear factor-kappa B activity. Phytother Res 2007; 21: 1082–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Fuentes NL, Sagua H, Morales G, et al. Experimental antihyperglycemic effect of diterpenoids of Laretia acaulis and Azorella compacta Phil (Umbelliferae) in rats. Phytother Res 2005; 19: 713–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Aniszewski T. Alkaloids: chemistry, biology, ecology, and applications. 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2015, pp. 1–475. [Google Scholar]

- 113. Wanders RJA, van Grunsven EG, Jansen GA. Lipid metabolism in peroxisomes: enzymology, functions and dysfunction of the fatty acid α and β oxidation system in humans. Biochem Soc Trans 2000; 28: 141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Muruganandan S, Srinivasan K, Gupta S, et al. Effect of mangiferin on hyperglycemia and atherogenicity in streptozotocin diabetic rats. J Ethnopharmacol 2005; 97: 497–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Gray AM, Flatt PR. Insulin-releasing and insulin-like activity of the traditional anti-diabetic plant Coriandrum sativum (coriander). Br J Nutr 1999; 81: 203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Huang THW, Teoha AW, Lina BL, et al. The role of herbal PPAR modulators in the treatment of cardiometabolic syndrome. Pharmacol Res 2009; 60: 195–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Babu PS, Prince PSM. Antihyperglycaemic and antioxidant effect of hyponid, an ayurvedic herbomineral formulation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J Pharm Pharmacol 2004; 56: 1435–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Panigrahy SK, Bhatt R, Kumar A. Reactive oxygen species: sources, consequences and targeted therapy in type-II diabetes. J Drug Target 2017; 25: 93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Kayaniyil S, Vieth R, Retnakaran R, et al. Association of vitamin D with insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction in subjects at risk for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2010; 33: 1379–1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Al-Timimi DJ, Ali AF. Serum 25(OH) D in diabetes mellitus type 2: relation to glycaemic control. J Clin Diagn Res 2013; 7: 2686–2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Talaei A, Mohamadi M, Adgi Z. The effect of vitamin D on insulin resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2013; 5: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Subramoniam A, Pushpangadan P, Rajasekharan S. Effects of Artemisia pallens Wall. on blood glucose levels in normal and alloxan-induced diabetic rats. J Ethnopharmacol 1996; 50: 13–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]