Abstract

Endometriosis is a fascinating disease that we strive to better understand. Molecular techniques are shedding new light on many important aspects of this disease: from pathogenesis to the recognition of distinct disease variants like deep infiltrating endometriosis. The observation that endometriosis is a cancer precursor has now been strengthened with the knowledge that mutations that are present in endometriosis-associated cancers can be found in adjacent endometriosis lesions. Recent genomic studies, placed in context, suggest that deep infiltrating endometriosis may represent a benign neoplasm that invades locally but rarely metastasises. Further research will help elucidate distinct aberrations which result in this phenotype. With respect to identifying those patients who may be at risk of developing endometriosis-associated cancers, a combination of molecular, pathological, and inheritance markers may define a high-risk group that might benefit from risk-reducing strategies.

Keywords: endometriosis, ovarian cancer, molecular mechanisms, biomarkers

Introduction

Endometriosis is a common and complex disease, affecting approximately 6–10% of women of reproductive age. The disease has a significant impact on women, as it is prevalent in greater than one-third of women with infertility and two-thirds of women with chronic pelvic pain [1]. Endometriosis is defined by the presence of ectopic endometrium (including glands and stroma) in extrauterine locations such as the rectovaginal septum, peritoneal surfaces, or ovaries [2]. The disease varies considerably in its presentation and severity. Patients experience a wide range of symptoms from asymptomatic disease to significant dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, and infertility [3]. Interestingly, symptom severity does not necessarily correlate with the clinical extent of disease, and disease progression can be highly unpredictable. These gynaecologic disorders rarely cause mortality; however, they may have a significant impact on a patient’s quality of life, and some cases may represent risk factors for gynaecologic malignancies such as cancer.

While practicing physicians are very familiar with the clinical features of endometriosis, emerging molecular technologies are enhancing our understanding of the disease in order to improve knowledge and treatment management. The purpose of this review paper is to discuss some of the recent progress that has been made as a result of the study of the molecular biology of endometriosis. Some of the key questions relating to the etiology, progression, and malignant transformation of endometriosis are now being clarified. In this review, we provide some interesting perspectives on this emerging information.

Risk factors and etiology of endometriosis

Significant risk factors for the development of endometriosis include conditions that increase the chances of retrograde menstruation and genetic/hereditary factors. Risk factors for endometriosis include early menarche, nulliparity, dysfunctional uterine bleeding, aberrant estrogen levels [4–7], and low body mass index [5]. Factors such as adequate exercise may be preventative against development of endometriosis [8]. It is known that the incidence of endometriosis in women with first-degree relatives who also have the disease may be up to ten times higher than that of the general population [9, 10]. There is likely to be a multifactorial genetic predisposition for endometriosis, and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have indicated single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) profiles which may increase the risk of endometriosis in individuals [11]. In 2012, Nyholt et al [12] identified 18 genomic regions harboring 38 putative endometriosis-associated SNPs in a GWAS involving 4,604 cases of endometriosis. Among the significant aberrations identified were SNPs associated with the WNT4 gene, known to be critical in reproductive tract differentiation and development in mammalian females [13, 14] as well as steroidigenesis [15], VEZT, shown to be downregulated in gastric cancers [16], and GREB1, an estrogen-regulated gene shown to be important in several hormone-responsive cancers [17, 18]. Another GWAS on 2,109 cases of endometriosis in 2013 performed by Albertsen et al also showed that SNPs associated with WNT4 were associated with the development of endometriosis [19], confirming results previously seen by Uno et al in 2010 [20] and Painter et al in 2011 [21]. A recent GWAS meta-analysis by Uimari et al in 2017 indicated certain cellular control pathways which were enriched in endometriosis; MAPK-related pathways controlling cell survival, migration, division, and gene expression, as well pathways involved in extracellular matrix structure [22]. Also in 2017, Sapkota et al identified five novel loci in sex steroid hormone pathways associated with endometriosis risk (FN1, CCDC170, ESR1, SYNE1 and FSHB) [23]. While GWAS data can provide an insight into genomic aberrations that predispose to endometriosis, further genetic and functional investigation is necessary in order to fully understand the underlying mechanisms responsible for the disease phenotype [24].

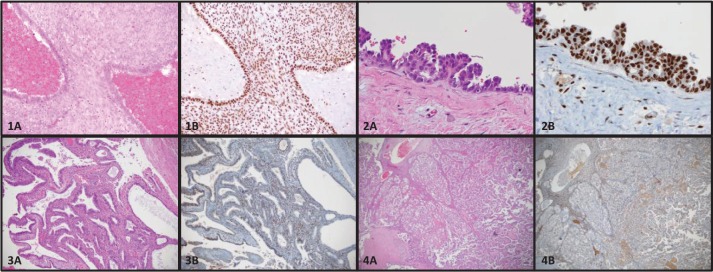

There are several theories pertaining to the origin of endometriotic lesions. Ectopic implants of endometrial tissue may arise by retrograde menstruation (the reflux of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity), resulting in the implantation and proliferation endometrial glands and stroma on extrauterine surfaces [25]. An alternate theory of coelomic metaplasia focuses on the de novo formation of endometrial glands and stroma by abnormal tissue differentiation from non-endometrial tissues [26]. Other common theories of origin suggest a lymphatic or haematogenous spread of endometrial tissue by dissemination through endothelial channels [27]. Based on recent molecular studies, it is interesting to speculate on the origins of endometriosis. Although there may be more than one possible explanation, current evidence supports the theory that endometriosis arises from the establishment, proliferation, and differentiation of a stem cell [28], or the implantation of endometrial cells secondary to retrograde menstruation. Stem cells can be extracted from menstrual blood and these cells show both mesenchymal and embryonic cell markers [29]. Presumably these stem cells have the capacity to give rise to both cell types (endometrial glands and stroma). Alternatively, retrograde menstruation and implantation of both endometrial glandular and stromal cells could give rise to endometriosis. Figure 1 (1A and 1B) shows an example of both glands and stroma in a typical endometriosis lesion.

Figure 1. Photomicrographs of endometriosis and EAOC stained by hematoxylin and eosin (A) or immunohistochemistry for BAF250a (B). 1) Typical endometriosis lesion (1A) maintaining BAF250a expression (1B). 2) Atypical endometriosis lesion (2A) demonstrating cellular hyperplasia maintaining BAF250a expression (2B). 3) Endometrioid ovarian carcinoma (3A) with BAF250a loss (3B). 4) Clear cell ovarian carcinoma (4A) with BAF250a loss (4B).

In a recent study of deep infiltrating endometriosis, mutations found in glandular epithelium were not found in surrounding stroma in both of the two cases analysed [30]. This suggests that the stroma could result from metaplastic change induced by the glandular epithelium. It is of interest in the development of patient-derived xenografts that the stromal tumour component is induced and derived from the mouse tissues [31, 32]. Eutopic endometrial cells with significant changes in their transcriptomes have been reported in women with endometriosis compared to women without endometriosis, indicating abnormalities that may predispose endometrial tissue to implant in extrauterine locations [33].

Interestingly, Barrett’s oesophagus is a disease that has been extensively studied and shares a number of important features with endometriosis, including an increased risk of cancer [34]. Barrett’s oesophagus was traditionally thought to result from the metaplastic transformation of squamous epithelium. Inflammation and cell injury from acid reflux results in the formation of glandular epithelium replacing the normal stratified squamous epithelium. Evidence now suggests that the ongoing inflammation imposes selection pressure for mucin-producing cells and that these cells can better resist the acidic environment [35]. Further research by a number of investigators suggests that the cell of origin may in fact reside in the submucosal glands of the oesophagus supporting the theory that transdifferentiation (metaplastic change) of the basal squamous cells may not give rise to the columnar epithelium [36–38]. This information provides little support for the theory that endometriosis is a metaplastic change of either peritoneum or embryonic rest cells, particularly when the differentiation of a single cell must result in two different cell types [39]. Knowing that deep-infiltrating endometriosis lesions display a unique somatic mutation signature and that distinct lesions have demonstrated clonal relatedness [30], we postulate that cases of extra-peritoneal endometriosis seem even less likely to have arisen from metaplastic changes and instead are likely the result of lymphatic or haematogenous spread. Further functional analyses are required to better understand the origin and establishment of endometriosis lesions.

Endometriosis as a cancer precursor: the historical perspective

A number of gynaecologic cancers of specific histotypes are thought to originate from endometriosis. In 1927, Sampson first published a report of a malignancy associated with endometriosis wherein he described specific criteria for endometriosis-associated ovarian cancers (EAOCs) [27]. First, there must be a clear example of endometriosis in association or close proximity to the cancer. In addition, no other primary tumour site must exist and the histology of the tumour must be consistent with an endometrial origin. Endometriosis is frequently described in association with clear cell and endometrioid ovarian cancers. A study by Vercellini et al in 1993 had showed a 26.3% history of endometriosis in women with endometrioid ovarian cancers (EnOC), 21.1% in clear cell ovarian cancers (CCC) [40]. The occurrence of synchronous endometriosis in ovarian cancer lesions was shown to be 40.6% in CCC, and 23.1% in EnOC in 1997 [41]. In a large Canadian database of ovarian cancers, endometriosis was identified in the final pathology reports in 51% of CCC and 43% of EnOC [42].

In 1953, RB Scott amended Sampson’s original criteria, to add an additional criterion stating that the endometriosis associated with cancers must show a morphologic progression from benign to malignant in a contiguous fashion. This transformation was further characterised by LaGrenade and Silverberg in 1988 who described what appeared to be a premalignant precursor, so-called atypical ovarian endometriosis [see Figure 1 (2A)] [43]. Atypical endometriosis [AE, see Figure 1 (2A and 2B)] may be seen relatively frequently associated with endometriosis-associated cancers. Reported rates of AE vary from 20% to 80% depending on the series [42–44]. Reasons for such variation in reported rates is that there is a lack of agreement on pathological criteria for the diagnosis of AE, and the diagnosis is uncommon, noted in only about 2–3% of endometriomas [45]. Stamp et al found that with more careful pathology review on archived formalin fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections, the diagnosis of AE was made twice as frequently on pathology review compared to the final diagnosis on the original reports. Moreover, these same authors searched the pathology records of a large tertiary hospital database spanning 15 years, and only 8 cases of AE were found in ovarian endometriomas without an associated cancer [42].

While endometriosis is a common disease, the overall risk of an endometriosis-associated cancer remains low. In a large epidemiological study, the overall frequency of ovarian cancer arising in a patient with a diagnosis of endometriosis was 0.3–0.8%, a risk that was 2–3 times higher than controls [46]. Interestingly, these epidemiological studies show an association with specific histological subtypes of ovarian cancer. This information supports the historical pathological observations that clear cell ovarian and endometrioid ovarian carcinomas may arise from endometriosis. Other neoplasms such as seromucinous borderline [47, 48], low-grade serous ovarian carcinomas [49], adenosarcomas [50, 51] and endometrial stromal sarcomas [52] may also arise from endometriosis [49, 53–55]. CCC and EnOC together represent the second and third most common epithelial ovarian cancers (approximately 20% of all cases) [56] and the only subtypes wherein a direct clonal relationship between endometriosis, as a direct precursor, and the cancer has been made [54, 57]. Better understanding of the precursor lesions which lead to these cancer types will improve their prevention and diagnosis.

Disease characteristics and clinical overview

The clinical diagnosis of endometriosis is challenging, as signs and symptoms may vary considerably and there is a lack of reliable diagnostic serum biomarkers [58]. Elevated levels of the biomarker CA-125 are not specific since they can indicate the presence of various gynaecologic pathologies, such as endometriosis, ovarian cancers or inflammation [59]. In some cases, levels of the serum biomarker HE4 can be used to distinguish endometriosis from ovarian and endometrial cancers [60]. In many patients, endometriosis is clinically suspected based on history and examination, and treated empirically with hormonal therapy (e.g., estrogen-progestin contraceptives or progestin-only therapies) without surgery [61]. A reliable diagnostic serum biomarker would represent a major advance for clinically diagnosing endometriosis [58].

Surgery with histological confirmation of ectopic endometrial glands and stroma remains [see Figure 1 (1A)] the gold standard for diagnosis [62, 63]. Surgery is generally reserved for patients who fail medical therapy, or who desire pregnancy, and is usually performed by laparoscopy [64–68]. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists are also used in severe cases. Other potential treatment options include hormone receptor (estrogen or progesterone) modulators, immune modulators, aromatase inhibitors, and anti-angiogenic drugs [69–71]. There are a number of excellent clinical reviews published on endometriosis. These manuscripts offer very comprehensive discussions of the clinical features of endometriosis and its treatment, and are therefore not further discussed in this review [64, 69, 72, 73].

There are three subtypes of endometriosis described in patients that can be clinically identified: ovarian endometriosis (endometriomas), superficial peritoneal endometriosis, and deep infiltrating endometriosis. Endometriotic lesions have been shown to have altered estrogen biosynthesis and are estrogen dependent. Estrogen dysregulation appears to be linked to increased aromatase expression and activity [74]. Additionally, resistance to the anti-proliferative effects of progesterone is associated with a shift in estrogen receptor isoform expression resulting in estrogen-mediated inhibition of progesterone receptor expression [75]. Furthermore, epigenetic alterations related to alterations in hormonal signaling pathways have also been reported [76]. In addition to imbalances in hormone regulation, oxidative stress caused by high iron levels has been reported to lead to increased levels of somatic mutations [77, 78]. Vercellini’s ‘incessant menstruation hypothesis’ [79] cites retrograde transport of blood, endometrial tissue, and carcinogens as potentially leading to the genesis of both endometriosis, as well as serous, endometrioid, and clear cell ovarian cancers. High levels of oxidative stress and iron exposure are the consequence of the inflammatory response that may arise from either retrograde menstruation or the endometriosis itself. Oxidative stress leads to increased angiogenesis, endometriosis proliferation, and selective iron-mediated DNA damage leading to potential oncogene mutations [80]. Local and systemic inflammatory responses likely play a key role in the cause of chronic pain and infertility [81–85]. Thus, inflammatory responses, along with the known hormonal dysregulation in endometriotic implants, may drive carcinogenesis [86]. While some EAOCs arise with obviously associated endometriosis, this is not always the case. Interestingly, many EAOC lack identifiable endometriotic precursor lesions as they may be destroyed by the resulting EAOC or simply not detected due to sampling limitations. We suspect, based on the frequency of adhesion formation in cases of EAOC, that the incidence of pre-existing endometriosis in such cases is very high.

Development of EAOC from endometriosis

The concept that endometriosis is the precursor lesion of some ovarian cancer subtypes has been supported by a number of lines of investigation. Initially as mentioned above, the association was noted by pathological methods, though epidemiological, and genetic studies have been valuable [25, 27, 40, 43, 44, 49, 87–92]. Jiang et al described some of the first studies suggesting a molecular basis linking endometriosis with cancer development in 1998. They demonstrated the same loss of heterozygosity (LOH) events in endometriosis lesions and adjacent endometrioid ovarian cancers in 82% of cases examined (n = 11) [87]. Similar evidence was reported by Prowse et al in 2006, who demonstrated common LOH events in both endometrioid and clear cell OCs and their associated endometriosis lesions, including both adjacent and contralateral endometriosis [90]. Additionally, LOH resulting in PTEN loss may be an early driver event in the genesis of in EAOC from endometriosis [93, 94]. Over the last 7 years, sequencing and immunohistochemical studies have provided confirmatory evidence that mutations found in endometriosis-associated cancers are found in adjacent endometriosis. These sequencing studies clearly demonstrate a clonal relationship between benign and malignant counterparts confirming that the cancers have fact arisen from the endometriotic lesions [42, 54, 57, 95].

Somatic mutations and other genomic aberrations are found in endometriosis that have been implicated in the development of cancer. Mutations in TP53 [96, 97] KRAS [30, 98], PTEN [94], PIK3CA [99, 100], and ARID1A gene regions [54, 57] have been described. Loss of expression of mismatch repair enzymes [101], microsatellite instability [102], and tissue-specific gene copy-number changes [103, 104], may also be seen in endometriosis lesions. LOH in endometriosis at known oncogenic loci is also frequently seen [94, 105–110]. SNPs that are associated with oncogenic transformation (seen in GWAS datasets) have been identified in cases of endometriosis [12, 19–21].

A high degree of inflammation, like that which is found in endometriosis, is a risk factor for the development of other cancers, similar to what is seen in some cases of Barrett’s oesophagus [111]. Dysregulation of gene expression in the complement pathway has been shown in endometriosis compared to normal tissues by Surwanyashi et al in 2014. The same authors also demonstrated linkages between upregulation of the complement pathway and upregulation of KRAS and PTEN-regulated pathways, both frequently involved in oncogenesis and maintenance of the cancer phenotype in vitro [112]. The complement pathway has been linked with supporting tumour growth through various mechanisms [113]. In 2015, Edwards et al demonstrated that 85% of atypical endometriosis lesions demonstrated a cancer-like immunological gene signature, compared to 30% of typical endometriosis lesions [114]. In 2015, a meta-analysis reported by Lee et al including over 15,000 ovarian cancer patients, evaluated the 38 putative endometriosis-associated SNPs identified by Nyholt in 2012 [12]. Eight of these were associated with significant risk for ovarian cancer (rs7515106, rs7521902, rs742356, rs4858692, rs1603995, rs4241991, rs6907340, and rs10777670) [115]. Also in 2015, Lu et al demonstrated shared genetic risk between endometriosis and epithelial ovarian cancer, particularly clear-cell and endometrioid histotypes using genome wide association (GWAS) datasets [89].

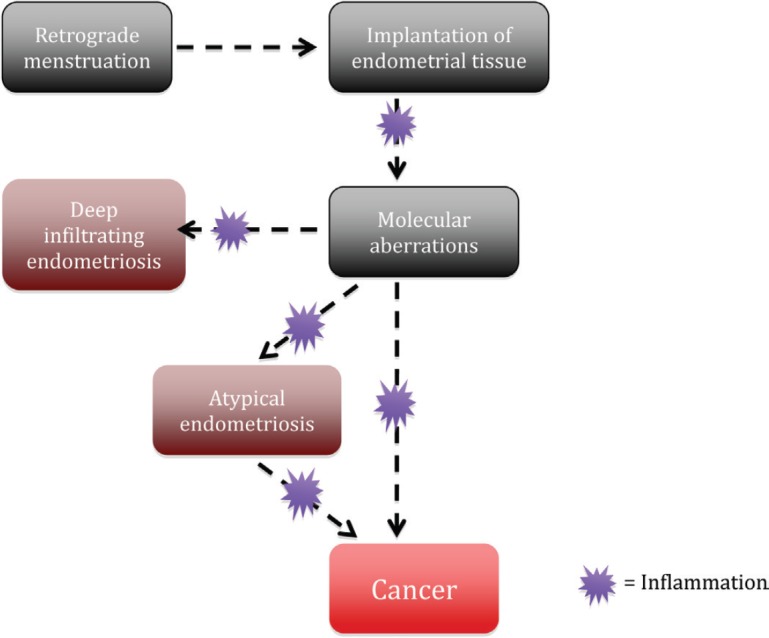

ARID1A is a tumour suppressor gene that was found to be mutated in a considerable number of EAOC [57]. Investigators were initially very excited to find that up to 42–61% of CCC and 21–33% EnOC show loss of the corresponding ARID1A gene protein expression (BAF250a) on IHC [see Figure 1 (3B)] [42, 57, 116]. ARID1A regulates important cellular functions (proliferation and genomic stability) as a tumour suppressor gene; therefore, it was thought that it might play a role in the transformation of endometriosis to cancer [117]. In 2015, Anglesio et al demonstrated that clear-cell ovarian carcinomas shared many mutations with associated concurrent endometriosis lesions, including mutations in ARID1A. Shared mutations in PIK3CA were also detected between endometriosis and clear-cell lesions, an event occurring in early progression mechanisms in other cancer types [54]. This study clearly demonstrated described mutations in contiguous endometriosis shared by EAOC, and even some distant lesions contained the same (PIK3CA and ARID1A) mutations. Studies examining BAF250a expression by IHC show that in just over half of the reported cases of EAOC, loss of BAF250a expression is seen the majority of the time (67–80%) in areas of contiguous endometriosis or atypical endometriosis (see Figure 1), and that a loss of Baf250a protein expression seemed to be an early molecular event in the development of Baf250a-negative EAOC [42, 95, 118]. Interestingly, ARID1A mutations are not sufficient on their own to cause cancer [119]. In support of this observation, Borrelli et al described partial loss of BAF250a in normal endometrium in the absence of cancer [120]. An important study recently reported that that 65% of cancer-causing genomic aberrations are random DNA repair abnormalities [121]. Taking this information into context, one can conclude that BAF250a loss in endometriosis could represent an EAOC precursor lesion; however, ARID1A mutations are neither a necessary driver mutation nor a significant determinant of the malignant phenotype. The presence of mutations in endometriosis is a sign of broader genomic disruption leading to the development of EAOC. Figure 2 shows a schematic of the establishment and evolution of endometriosis lesions to EAOC. Studies have been done comparing patient outcomes in EAOC based on the presence or absence of BAF250a expression. Based on the available evidence, it has yet to be determined as to whether there are differences in prognosis or treatment outcomes related to BAF250a loss in EAOC [122, 123]. There are few identifiable proteomic changes in a panel of proteins evaluated by reverse phase protein array (RPPA) suggesting that BAF250a loss does not define a specific proteomic signature [124]. Additionally, the presence or absence of an endometriosis precursor lesion in EAOC has not been associated with a change in overall disease outcome [125].

Figure 2. Potential process of the establishment and evolution of endometriosis lesions to EAOCs.

Endometriosis as a neoplasm

Deep infiltrating endometriosis is an interesting rare subtype of endometriosis which was recently subjected to genomic evaluation. Deep endometriosis has a propensity to locally invade surrounding structures (bowel, bladder, ureter) but rarely metastasises. Anglesio et al demonstrated the presence of somatic mutation events in 79% of 24 cases, with 26% of all cases screened harbouring statistically significant somatic mutations in known cancer driver genes such as KRAS, PIK3CA, ARID1A, and PPP2R1A. In the analysis of a smaller subset of samples, mutations in KRAS found to be present in the epithelial component of endometriosis lesions were absent in the stroma. Additionally, one patient was found to have the same KRAS mutation in three spatially distinct endometriosis lesions. While these molecular events are commonly found in EAOCs, this study demonstrated their presence in deep infiltrating endometriosis. While traditionally oncogenic driver mutations (like KRAS) were present in a quarter of samples, they did not appear to indicate the likelihood of the lesion to progress into a gynaecologic cancer nor appear to be required for the development of the deep-infiltrating lesions. This suggests that additional or different molecular mechanisms may be at play in the development of endometriosis, and future research using a broad array of molecular technologies (epigenetic, splicing aberrations, complex chromosomal rearrangements, transcriptome, proteome and post-translational changes) to investigate the functional biology of endometriosis is warranted. Novel molecular technologies may also help explain the biology of clonally identical lesions in the same patient. Finally, the unusual presence of endometriosis in lymph nodes has been described, with some cases showing BAF250a loss [120]. Thus, one might expect that these very unusual cases are molecularly distinct as they mimic locally metastatic cancers. Perhaps even the deep-infiltrating subtype of endometriosis, which demonstrates unequivocal invasion of surrounding tissues, may be more appropriately considered a neoplasm than a benign condition. Better understanding of the molecular pathology of this disease may provide useful strategies to diagnose and treat complex cases, with the goal of reducing morbidity and disease complications like infertility.

Prevention strategies for EAOCs

Endometriosis is highly prevalent in women of reproductive age, causing dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, infertility and in some instances even cancer. With our rapidly advancing knowledge of neoplastic diseases and modern technologies, the application of molecular science will hopefully provide us with an opportunity to identify the etiology of endometriosis, and the patients with endometriosis who are at risk of developing cancer. In order to separate patients at risk of EAOC from those who will continue to have benign disease, the application of highly sensitive and specific novel molecular biomarkers should be explored. Likely a combination of epidemiological, pathological and molecular risk stratification will be required. The finding of atypical endometriosis in the absence of cancer is rare and the risk of developing cancer in such cases is unknown. Pearce et al [53] showed that women with a history of endometriosis in higher-risk genetic groups had up to a 4–9% lifetime risk of developing ovarian cancer after statistical adjustment for oral contraceptive use and parity. This high-risk group represented 1.8% of the total study population of over 5,000 women with ovarian cancer. This type of risk stratification could serve to identify a baseline population for further follow-up and molecular testing.

Additional research should be directed to the discovery of biomarkers that identify cases of endometriosis with oncogenic potential, the goal being to identify premalignant lesions and then study subsequent interventions in order to reduce the incidence of EAOCs and improve patient outcomes. Various technologies may be useful in the quest for biomarker discovery. Proteomic analysis by mass spectrometry of endometrial fluid from women with and without endometriosis has been used to putatively examine differential protein signatures between normal and gynaecologic disease conditions [126–128]. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) can now be detected in blood and the presence of cancer-specific mutations may prove to be clinically useful for the diagnosis of both primary and recurrent disease, determining prognosis, and predicting treatment responses [129, 130]. Thus, studying ctDNA could also play a role in the early detection of genomic dysregulation of cancer precursor lesions now known to be present in some patients with endometriosis [131]. In rare cases of atypical endometriosis not associated with cancer, biomarker research could theoretically identify those cases with true oncogenic potential. Future research efforts should also focus on establishing model systems of endometriosis (such as cell lines or xenografts). These studies could offer important insights into the risk factors, subtype-specific molecular traits, novel therapeutic testing, and the factors responsible for the development of EAOCs.

While we work with these new technologies to identify biomarkers of EAOC risk, it is important to highlight current interventions that are known to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer, including EnOC and CCC. Regular use of the oral contraceptive pill for 5 years results in a 20–30% reduction in EnOC and CCC risk [132]. Similarly, tubal ligation is at least as effective as the oral contraceptive in reducing the risk of EAOCs, showing a reduction in EnOC and CCC risk of almost 50% [133]. As the fallopian tube is the likely conduit for key factors resulting in the etiology and propagation of endometriosis, tubal occlusion is an important consideration for those women looking for permanent contraception. In these women, opportunistic salpingectomy also has the potential to reduce their risk of serous ovarian cancers and should be considered [134–137]. The latter strategy has been shown to be cost-effective [138–140].

Further research is needed to determine the role of risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) to prevent EAOCs. One recent cost-effectiveness study suggests that BSO could be used in patients who have an overall lifetime risk of ovarian cancer higher than 4% [141]. In these cases, compliance with hormone replacement therapy must be high in order to mitigate the potential long-term adverse health effects of premature menopause [142].

Conclusion

For those women who are having surgery for endometriomas close to menopause, unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy may be considered if the endometrioma cannot be completely removed by cystectomy as most cases of EAOC arise from endometriomas. Finally, understanding the molecular biology of endometriosis will be the key to better treatments for endometriosis and guide future early detection and prevention strategies to further reduce the incidence and mortality of EAOCs.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

Supporting research performed by the authors was funded in part through the Cararresi Foundation (OvCaRe Research Grant), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the British Columbia Cancer Foundation (BCCF), and the VGH-UBC Hospital Foundation.

References

- 1.Gynecologists ACoOa. Management of endometriosis. Clinical Management Guidelines of Obstetricians/Gynecologists. 2010;116(1):223–236. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapron C, Chopin N, Borghese B, et al. Deeply infiltrating endometriosis: pathogenetic implications of the anatomical distribution. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(7):1839–1845. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tosti C, Pinzauti S, Santulli P, et al. Pathogenetic mechanisms of deep infiltrating endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2015;22(9):1053–1059. doi: 10.1177/1933719115592713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darrow SL, Vena JE, Batt RE, et al. Menstrual cycle characteristics and the risk of endometriosis. Epidemiology. 1993;4(2):135–142. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199303000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Signorello LB, Harlow BL, Cramer DW, et al. Epidemiologic determinants of endometriosis: a hospital-based case-control study. Ann Epidemiol. 1997;7(4):267–741. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(97)00017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cramer DW, Missmer SA. The epidemiology of endometriosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;955:11–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb02761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Candiani GB, Danesino V, Gastaldi A, et al. Reproductive and menstrual factors and risk of peritoneal and ovarian endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1991;56(2):230–234. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)54477-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kvaskoff M, Bijon A, Clavel-Chapelon F, et al. Childhood and adolescent exposures and the risk of endometriosis. Epidemiology. 2013;24(2):261–269. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3182806445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matalliotakis IM, Arici A, Cakmak H, et al. Familial aggregation of endometriosis in the yale series. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;278(6):507–511. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0644-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Treloar SA, O’Connor DT, O’Connor, et al. Genetic influences on endometriosis in an Australian twin sample. Fertil Steril. 1999;71(4):701–710. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(98)00540-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahmioglu N, Nyholt DR, Morris AP, et al. Genetic variants underlying risk of endometriosis: insights from meta-analysis of eight genome-wide association and replication datasets. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(5):702–716. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmu015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nyholt DR, Low SK, Anderson CA, et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis identifies new endometriosis risk loci. Nat Genet. 2012;44(12):1355–1359. doi: 10.1038/ng.2445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaaskelainen M, Prunskaite-Hyyrylainen R, Naillat F, et al. WNT4 is expressed in human fetal and adult ovaries and its signaling contributes to ovarian cell survival. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;317(1–2):106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vainio S, Heikkila M, Kispert A, et al. Female development in mammals is regulated by Wnt-4 signalling. Nature. 1999;397(6718):405–409. doi: 10.1038/17068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyer A, Lapointe E, Zheng X, et al. WNT4 is required for normal ovarian follicle development and female fertility. FASEB J. 2010;24(8):3010–3025. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-145789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo X, Jing C, Li L, et al. Down-regulation of VEZT gene expression in human gastric cancer involves promoter methylation and miR-43c. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;404(2):622–627. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rae JM, Johnson MD, Scheys JO, et al. GREB 1 is a critical regulator of hormone dependent breast cancer growth. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;92(2):141–149. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-1483-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghosh MG, Thompson DA, Weigel RJ. PDZK1 and GREB1 are estrogen-regulated genes expressed in hormone-responsive breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60(22):6367–6375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albertsen HM, Chettier R, Farrington P, et al. Genome-wide association study link novel loci to endometriosis. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e58257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uno S, Zembutsu H, Hirasawa A, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies genetic variants in the CDKN2BAS locus associated with endometriosis in Japanese. Nat Genet. 2010;42(8):707–710. doi: 10.1038/ng.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Painter JN, Anderson CA, Nyholt DR, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a locus at 7p15.2 associated with endometriosis. Nat Genet. 2011;43(1):51–54. doi: 10.1038/ng.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uimari O, Rahmioglu N, Nyholt DR, et al. Genome-wide genetic analyses highlight mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(4):780–793. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sapkota Y, Steinthorsdottir V, Morris AP, et al. Meta-analysis identifies five novel loci associated with endometriosis highlighting key genes involved in hormone metabolism. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15539. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fung JN, Rogers PA, Montgomery GW. Identifying the biological basis of GWAS hits for endometriosis. Biol Reprod. 2015;92(4):87. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.114.126458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sampson JA. Peritoneal endometriosis due to the menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1927;14:422–469. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(15)30003-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferguson BR, Bennington JL, Haber SL. Histochemistry of mucosubstances and histology of mixed mullerian pelvic lymph node glandular inclusions. evidence for histogenesis by mullerian metaplasia of coelomic epithelium. Obstet Gynecol. 1969;33(5):617–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sampson JA. Metastatic or embolic endometriosis, due to the menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the venous circulation. Am J Pathol. 1927;3(2):93–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lagana AS, Vitale SG, Salmeri FM, et al. Unus pro omnibus, omnes pro uno: a novel, evidence-based, unifying theory for the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Med Hypotheses. 2017;103:10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2017.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodrigues MC, Lippert T, Nguyen H, et al. Menstrual blood-derived stem cells: in vitro and in vivo characterization of functional effects. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;951:111–121. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-45457-3_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anglesio MS, Papadopoulos N, Ayhan A, et al. Cancer-associated mutations in endometriosis without cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(19):1835–1848. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hidalgo M, Amant F, Biankin AV, et al. Patient-derived xenograft models: an emerging platform for translational cancer research. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(9):998–1013. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schneeberger VE, Allaj V, Gardner EE, et al. Quantitation of murine stroma and selective purification of the human tumor component of patient-derived xenografts for genomic analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0160587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao L, Gu C, Ye M, et al. Identification of global transcriptome abnormalities and potential biomarkers in eutopic endometria of women with endometriosis: a preliminary study. Biomed Rep. 2017;6(6):654–662. doi: 10.3892/br.2017.902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jansen M, Wright N. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology Series. Stem Cells, Pre-neoplasia and Early Cancer of the Upper Gastrointestinal Tract. Vol. 908. Switzerland: Springer; 2016. p. 486. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Evans JA, McDonald SA. The complex, clonal, and controversial nature of barrett’s esophagus. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;908:27–40. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-41388-4_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garman KS. Origin of barrett’s epithelium: esophageal submucosal glands. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;4(1):153–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lorinc E, Oberg S. Submucosal glands in the columnar-lined oesophagus: evidence of an association with metaplasia and neosquamous epithelium. Histopathology. 2012;61(1):53–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2012.04180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lorinc E, Oberg S. Hyperplasia of the submucosal glands of the columnar-lined oesophagus. Histopathology. 2015;66(5):726–731. doi: 10.1111/his.12604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang DH, Souza RF. Transcommitment: paving the way to barrett’s Metaplasia. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;908:183–212. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-41388-4_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vercellini P, Parazzini F, Bolis G, et al. Endometriosis and ovarian cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169(1):181–182. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90159-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jimbo H, Yoshikawa H, Onda T, et al. Prevalence of ovarian endometriosis in epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997;59(3):245–250. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(97)00238-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stamp JP, Gilks CB, Wesseling M, et al. BAF250a expression in atypical endometriosis and endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016;26(5):825–832. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.LaGrenade A, Silverberg SG. Ovarian tumors associated with atypical endometriosis. Hum Pathol. 1988;19(9):1080–1084. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(88)80090-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fukunaga M, Nomura K, Ishikawa E, et al. Ovarian atypical endometriosis: its close association with malignant epithelial tumours. Histopathology. 1997;30(3):249–255. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1997.d01-592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bedaiwy MA, Hussein MR, Biscotti C, et al. Pelvic endometriosis is rarely associated with ovarian borderline tumours, cytologic and architectural atypia: a clinicopathologic study. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15(1):81–88. doi: 10.1007/s12253-008-9072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wei JJ, William J, Bulun S. Endometriosis and ovarian cancer: a review of clinical, pathologic, and molecular aspects. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2011;30(6):553–568. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e31821f4b85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maeda D, Shih Ie M. Pathogenesis and the role of ARID1A mutation in endometriosis-related ovarian neoplasms. Adv Anat Pathol. 2013;20(1):45–52. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e31827bc24d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Samartzis EP, Noske A, Dedes KJ, et al. ARID1A mutations and PI3K/AKT pathway alterations in endometriosis and endometriosis-associated ovarian carcinomas. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(9):18824–18849. doi: 10.3390/ijms140918824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pearce CL, Templeman C, Rossing MA, et al. Association between endometriosis and risk of histological subtypes of ovarian cancer: a pooled analysis of case-control studies. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(4):385–394. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70404-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kondi-Pafiti A, Spanidou-Carvouni H, Papadias K, et al. Malignant neoplasms arising in endometriosis: clinicopathological study of 14 cases. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2004;31(4):302–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang C, Oh HK, Kim D. Mullerian adenosarcoma arising from rectal endometriosis. Ann Coloproctol. 2014;30(5):232–236. doi: 10.3393/ac.2014.30.5.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Masand RP, Euscher ED, Deavers MT, et al. Endometrioid stromal sarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 63 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37(11):1635–1647. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pearce CL, Stram DO, Ness RB, et al. Population distribution of lifetime risk of ovarian cancer in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(4):671–676. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anglesio MS, Bashashati A, Wang YK, et al. Multifocal endometriotic lesions associated with cancer are clonal and carry a high mutation burden. J Pathol. 2015;236(2):201–209. doi: 10.1002/path.4516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu HC, Lin CY, Chang WC, et al. Increased association between endometriosis and endometrial cancer: a nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25(3):447–452. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Anglesio MS, Carey MS, Kobel M, et al. Clear cell carcinoma of the ovary: a report from the first Ovarian Clear Cell Symposium, June 24th, 2010. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121(2):407–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wiegand KC, Shah SP, Al-Agha OM, et al. ARID1A mutations in endometriosis-associated ovarian carcinomas. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(16):1532–1543. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Berker B, Seval M. Problems with the diagnosis of endometriosis. Womens Health (Lond) 2015;11(5):597–601. doi: 10.2217/whe.15.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moss EL, Hollingworth J, Reynolds TM. The role of CA125 in clinical practice. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58(3):308–312. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.018077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huhtinen K, Suvitie P, Hiissa J, et al. Serum HE4 concentration differentiates malignant ovarian tumours from ovarian endometriotic cysts. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(8):1315–1319. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Leyland N, Casper R, Laberge P, et al. Endometriosis: diagnosis and management. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2010;32(7 Suppl 2):S1–32. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34589-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wykes CB, Clark TJ, Khan KS. Accuracy of laparoscopy in the diagnosis of endometriosis: a systematic quantitative review. BJOG. 2004;111(11):1204–1212. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hori Y, Committee SG. Diagnostic laparoscopy guidelines : this guideline was prepared by the SAGES guidelines committee and reviewed and approved by the Board of Governors of the society of American gastrointestinal and endoscopic surgeons (SAGES), November 2007. Surg Endosc. 2008;22(5):1353–1383. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9759-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Burney RO, Giudice LC. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(3):511–519. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Eskenazi B, Warner ML. Epidemiology of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1997;24(2):235–258. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8545(05)70302-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rogers PA, D’Hooghe TM, Fazleabas A, et al. Defining future directions for endometriosis research: workshop report from the 2011 World Congress of Endometriosis in Montpellier, France. Reprod Sci. 2013;20(5):483–499. doi: 10.1177/1933719113477495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Burghaus S, Haberle L, Schrauder MG, et al. Endometriosis as a risk factor for ovarian or endometrial cancer – results of a hospital-based case-control study. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:751. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1821-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wykes CB, Clark TJ, Chakravati S, et al. Efficacy of laparoscopic excision of visually diagnosed peritoneal endometriosis in the treatment of chronic pelvic pain. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;125(1):129–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bedaiwy MA, Alfaraj S, Yong P, et al. New developments in the medical treatment of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2017;107(3):555–565. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Streuli I, de Ziegler D, Borghese B, et al. New treatment strategies and emerging drugs in endometriosis. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2012;17(1):83–104. doi: 10.1517/14728214.2012.668885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Streuli I, de Ziegler D, Santulli, et al. An update on the pharmacological management of endometriosis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2013;14(3):291–305. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2013.767334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2004;364(9447):1789–1799. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kobayashi H. Ovarian cancer in endometriosis: epidemiology, natural history, and clinical diagnosis. Int J Clin Oncol. 2009;14(5):378–382. doi: 10.1007/s10147-009-0931-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bukulmez O, Hardy DB, Carr BR, et al. Inflammatory status influences aromatase and steroid receptor expression in endometriosis. Endocrinology. 2008;149(3):1190–1204. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Han SJ, O’Malley BW. The dynamics of nuclear receptors and nuclear receptor coregulators in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(4):467–484. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmu002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Guo SW. Epigenetics of endometriosis. Mol Hum Reprod. 2009;15(10):587–607. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gap064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kobayashi H, Imanaka S, Nakamura H, et al. Understanding the role of epigenomic, genomic and genetic alterations in the development of endometriosis (review) Mol Med Rep. 2014;9(5):1483–1505. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kobayashi H, Yamada Y, Kanayama S, et al. The role of iron in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2009;25(1):39–52. doi: 10.1080/09513590802366204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vercellini P, Crosignani P, Somigliana E, et al. The ‘incessant menstruation’ hypothesis: a mechanistic ovarian cancer model with implications for prevention. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(9):2262–2273. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Toyokuni S. Role of iron in carcinogenesis: cancer as a ferrotoxic disease. Cancer Sci. 2009;100(1):9–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.01001.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ota H, Igarashi S, Sasaki M, et al. Distribution of cyclooxygenase-2 in eutopic and ectopic endometrium in endometriosis and adenomyosis. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(3):561–566. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.3.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lin YJ, Lai MD, Lei HY, et al. Neutrophils and macrophages promote angiogenesis in the early stage of endometriosis in a mouse model. Endocrinology. 2006;147(3):1278–1286. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ahn SH, Edwards AK, Singh SS, et al. IL-17A contributes to the pathogenesis of endometriosis by triggering proinflammatory cytokines and angiogenic growth factors. J Immunol. 2015;195(6):2591–2600. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang X, Xu H, Lin J, et al. Peritoneal fluid concentrations of interleukin-17 correlate with the severity of endometriosis and infertility of this disorder. BJOG. 2005;112(8):1153–1155. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McKinnon BD, Bertschi D, Bersinger NA, et al. Inflammation and nerve fiber interaction in endometriotic pain. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015;26(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Worley MJ, Welch WR, Berkowitz RS, et al. Endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer: a review of pathogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(3):5367–5379. doi: 10.3390/ijms14035367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jiang X, Morland SJ, Hitchcock A, et al. Allelotyping of endometriosis with adjacent ovarian carcinoma reveals evidence of a common lineage. Cancer Res. 1998;58(8):1707–1712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Scott RB. Malignant changes in endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1953;2(3):283–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lu Y, Cuellar-Partida G, Painter JN, et al. Shared genetics underlying epidemiological association between endometriosis and ovarian cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(20):5955–5964. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Prowse AH, Manek S, Varma R, et al. Molecular genetic evidence that endometriosis is a precursor of ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2006;119(3):556–562. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.McMeekin DS, Burger RA, Manetta A, et al. Endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the ovary and its relationship to endometriosis. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;59(1):81–86. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1995.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sainz de la Cuesta R, Eichhorn JH, Rice LW, et al. Histologic transformation of benign endometriosis to early epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;60(2):238–244. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Worley MJ, Jr., Liu S, Hua Y, et al. Molecular changes in endometriosis-associated ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(13):1831–1842. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sato N, Tsunoda H, Nishida M, et al. Loss of heterozygosity on 10q23.3 and mutation of the tumor suppressor gene PTEN in benign endometrial cyst of the ovary: possible sequence progression from benign endometrial cyst to endometrioid carcinoma and clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. Cancer Res. 2000;60(24):7052–7056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chene G, Ouellet V, Rahimi K, et al. The ARID1A pathway in ovarian clear cell and endometrioid carcinoma, contiguous endometriosis, and benign endometriosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;130(1):27–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bischoff FZ, Heard M, Simpson JL. Somatic DNA alterations in endometriosis: high frequency of chromosome 17 and p53 loss in late-stage endometriosis. J Reprod Immunol. 2002;55(1–2):49–64. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0378(01)00131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sainz de la Cuesta R, Izquierdo M, Canamero M, et al. Increased prevalence of p53 overexpression from typical endometriosis to atypical endometriosis and ovarian cancer associated with endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;113(1):87–93. doi: 10.1016/S0301-2115(03)00367-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Vestergaard AL, Thorup K, Knudsen UB, et al. Oncogenic events associated with endometrial and ovarian cancers are rare in endometriosis. Mol Hum Reprod. 2011;17(12):758–761. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gar049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Laudanski P, Szamatowicz J, Kowalczuk O, et al. Expression of selected tumor suppressor and oncogenes in endometrium of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(8):1880–1890. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yamamoto S, Tsuda H, Takano M, et al. PIK3CA mutation is an early event in the development of endometriosis-associated ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma. J Pathol. 2011;225(2):189–194. doi: 10.1002/path.2940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Grassi T, Calcagno A, Marzinotto S, et al. Mismatch repair system in endometriotic tissue and eutopic endometrium of unaffected women. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(2):1867–1877. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Fuseya C, Horiuchi A, Hayashi A, et al. Involvement of pelvic inflammation-related mismatch repair abnormalities and microsatellite instability in the malignant transformation of ovarian endometriosis. Hum Pathol. 2012;43(11):1964–1972. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yang W, Zhang Y, Fu F, et al. High-resolution array-comparative genomic hybridization profiling reveals 20q13.33 alterations associated with ovarian endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013;29(6):603–607. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2013.788632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mafra F, Mazzotti D, Pellegrino R, et al. Copy number variation analysis reveals additional variants contributing to endometriosis development. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016;34(1):117–124. doi: 10.1007/s10815-016-0822-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ali-Fehmi R, Khalifeh I, Bandyopadhyay S, et al. Patterns of loss of heterozygosity at 10q23.3 and microsatellite instability in endometriosis, atypical endometriosis, and ovarian carcinoma arising in association with endometriosis. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2006;25(3):223–229. doi: 10.1097/01.pgp.0000192274.44061.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Xu B, Hamada S, Kusuki I, et al. Possible involvement of loss of heterozygosity in malignant transformation of ovarian endometriosis. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;120(2):239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Obata K, Hoshiai H. Common genetic changes between endometriosis and ovarian cancer. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2000;50(Suppl 1):39–43. doi: 10.1159/000052877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Thomas EJ, Campbell IG. Molecular genetic defects in endometriosis. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2000;50(Suppl 1):44–50. doi: 10.1159/000052878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jiang X, Hitchcock A, Bryan EJ, et al. Microsatellite analysis of endometriosis reveals loss of heterozygosity at candidate ovarian tumor suppressor gene loci. Cancer Res. 1996;56(15):3534–3539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Silveira CG, Abrao MS, Dias JA, Jr., et al. Common chromosomal imbalances and stemness-related protein expression markers in endometriotic lesions from different anatomical sites: the potential role of stem cells. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(11):3187–3197. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kapoor H, Agrawal DK, Mittal SK. Barrett’s esophagus: recent insights into pathogenesis and cellular ontogeny. Transl Res. 2015;166(1):28–40. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Suryawanshi S, Huang X, Elishaev E, et al. Complement pathway is frequently altered in endometriosis and endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(23):6163–6174. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Rutkowski MJ, Sughrue ME, Kane AJ, et al. Cancer and the complement cascade. Mol Cancer Res. 2010;8(11):1453–1465. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-10-0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Edwards RP, Huang X, Vlad AM. Chronic inflammation in endometriosis and endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer: New roles for the “old” complement pathway. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4(5):e1002732. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2014.1002732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lee AW, Templeman C, Stram DA, et al. Evidence of a genetic link between endometriosis and ovarian cancer. Fertil Steril. 2015;105(1):35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Yamamoto S, Tsuda H, Takano M, et al. Loss of ARID1A protein expression occurs as an early event in ovarian clear-cell carcinoma development and frequently coexists with PIK3CA mutations. Mod Pathol. 2012;25(4):615–624. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wu RC, Wang TL, Shih Ie M. The emerging roles of ARID1A in tumor suppression. Cancer Biol Ther. 2014;15(6):655–664. doi: 10.4161/cbt.28411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nishikimi K, Kiyokawa T, Tate S, et al. ARID1A expression in ovarian clear cell carcinoma with an adenofibromatous component. Histopathology. 2015;67(6):866–871. doi: 10.1111/his.12721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Guan B, Rahmanto YS, Wu RC, et al. Roles of deletion of Arid1a, a tumor suppressor, in mouse ovarian tumorigenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(7):dju146. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Borrelli GM, Abrao MS, Taube ET, et al. (Partial) Loss of BAF250a (ARID1A) in rectovaginal deep-infiltrating endometriosis, endometriomas and involved pelvic sentinel lymph nodes. Mol Hum Reprod. 2016;22(5):329–337. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaw009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tomasetti C, Vogelstein B. Cancer etiology. variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions. Science. 2015;347(6217):78–81. doi: 10.1126/science.1260825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Katagiri A, Nakayama K, Rahman MT, et al. Loss of ARID1A expression is related to shorter progression-free survival and chemoresistance in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2012;25(2):282–288. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Lowery WJ, Schildkraut JM, Akushevich L, et al. Loss of ARID1A-associated protein expression is a frequent event in clear cell and endometrioid ovarian cancers. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2012;22(1):9–14. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e318231f140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wiegand KC, Hennessy BT, Leung S, et al. A functional proteogenomic analysis of endometrioid and clear cell carcinomas using reverse phase protein array and mutation analysis: protein expression is histotype-specific and loss of ARID1A/BAF250a is associated with AKT phosphorylation. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:120. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Minlikeeva AN, Freudenheim JL, Eng KH, et al. History of comorbidities and survival of ovarian cancer patients, results from the ovarian cancer association consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(9):1470–1473. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ametzazurra A, Matorras R, Garcia-Velasco JA, et al. Endometrial fluid is a specific and non-invasive biological sample for protein biomarker identification in endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(4):954–965. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Casado-Vela J, Rodriguez-Suarez E, Iloro I, et al. Comprehensive proteomic analysis of human endometrial fluid aspirate. J Proteome Res. 2009;8(10):4622–4632. doi: 10.1021/pr9004426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Yang H, Lau WB, Lau B, et al. A mass spectrometric insight into the origins of benign gynecological disorders. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2015;36(3):450–470. doi: 10.1002/mas.21484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Di Meo A, Bartlett J, Cheng Y, et al. Liquid biopsy: a step forward towards precision medicine in urologic malignancies. Mol Cancer. 2017;16(1):80. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0644-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Perakis S, Speicher MR. Emerging concepts in liquid biopsies. BMC Med. 2017;15(1):75. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0840-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Offin M, Chabon JJ, Razavi P, et al. Capturing genomic evolution of lung cancers through liquid biopsy for circulating tumor DNA. J Oncol. 2017;2017:4517834. doi: 10.1155/2017/4517834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Collaborative Group on Epidemiological Studies of Ovarian C. Beral V, Doll R, et al. Ovarian cancer and oral contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of data from 45 epidemiological studies including 23,257 women with ovarian cancer and 87,303 controls. Lancet. 2008;371(9609):303–314. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60167-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Gaitskell K, Green J, Pirie K, et al. Tubal ligation and ovarian cancer risk in a large cohort: Substantial variation by histological type. Int J Cancer. 2016;138(5):1076–1084. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Chene G, de Rochambeau B, Le Bail-Carval K, et al. Current surgical practice of prophylactic and opportunistic salpingectomy in France. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2016;44(7–8):377–384. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Chene G, Caloone J, Moret S, et al. Is endometriosis a precancerous lesion? Perspectives and clinical implications. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2016;44(2):106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Cibula D, Widschwendter M, Majek O, et al. Tubal ligation and the risk of ovarian cancer: review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17(1):55–67. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmq030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Kwon JS. Ovarian cancer risk reduction through opportunistic salpingectomy. J Gynecol Oncol. 2015;26(2):83–86. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2015.26.2.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Tai RWM, Choi SKY, Coyte PC. The cost-effectiveness of salpingectomies for family planning in the prevention of ovarian cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2017;S1701–S2163(17):30493–30500. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2017.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Dilley SE, Havrilesky LJ, Bakkum-Gamez J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of opportunistic salpingectomy for ovarian cancer prevention. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;146(2):373–379. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Kwon JS, McAlpine JN, Hanley GE, et al. Costs and benefits of opportunistic salpingectomy as an ovarian cancer prevention strategy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(2):338–345. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Manchanda R, Legood R, Antoniou AC, et al. Specifying the ovarian cancer risk threshold of ‘premenopausal risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy’ for ovarian cancer prevention: a cost-effectiveness analysis. J Med Genet. 2016;53(9):591–599. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-103800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Parker WH, Feskanich D, Broder MS, et al. Long-term mortality associated with oophorectomy compared with ovarian conservation in the nurses’ health study. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(4):709–716. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182864350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]