Abstract

Background

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) secondary to rupture of a blister aneurysm (BA) results in high morbidity and mortality. Endovascular treatment with the pipeline embolization device (PED) has been described as a new treatment strategy for these lesions. We present the first reported case of PED retraction and foreshortening after treatment of a ruptured internal carotid artery (ICA) BA.

Case description

A middle-aged patient presented with SAH secondary to ICA BA rupture. The patient was treated with telescoping PED placement across the BA. After 5 days from treatment, the patient developed a new SAH due to re-rupture of the BA. Digital subtraction angiography revealed an increase in caliber of the supraclinoid ICA with associated retraction and foreshortening of the PED that resulted in aneurysm uncovering and growth.

Conclusions

PED should be oversized during ruptured BA treatment to prevent device retraction and aneurysm regrowth. Frequent imaging follow up after BA treatment with PED is warranted to ensure aneurysm occlusion.

Keywords: Blister aneurysm, subarachnoid hemorrhage, pipeline, embolization, foreshortening

Introduction

A middle-aged patient presented with subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) secondary to internal carotid artery (ICA) blister aneurysm (BA) rupture. The patient was treated with telescoping pipeline embolization device (PED) placement across the BA. After 5 days from treatment, the patient developed a new SAH due to re-rupture of the BA. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) revealed an increase in caliber of the supraclinoid ICA with associated retraction and foreshortening of the PED that resulted in aneurysm uncovering and growth. This is the first reported case of PED retraction and foreshortening after treatment of a ruptured ICA BA.

Case description

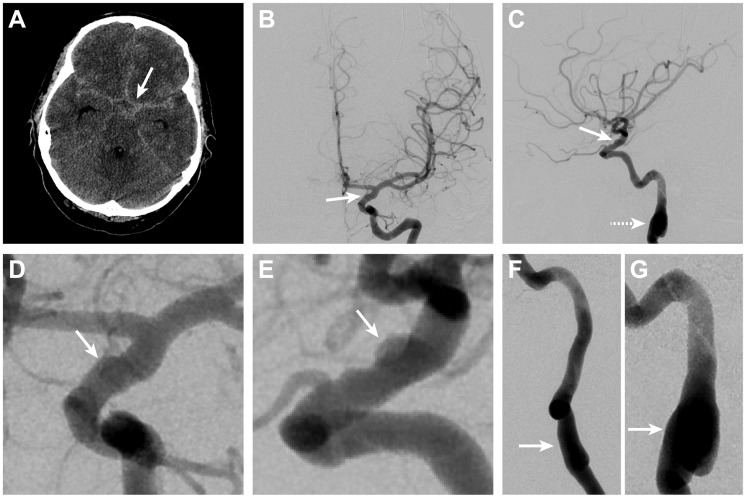

A middle-aged patient with no known past medical history developed a severe headache due to SAH (Figure 1). At presentation, the patient’s Hunt and Hess Scale score was 2, Glasgow Coma Scale score was 15, and modified Fisher Grade score was 3. A DSA identified a left ICA BA (Figure 1) and bilateral cervical ICA dissections (Figure 1), which raised suspicion for an undiagnosed connective tissue disorder. A multidisciplinary discussion regarding treatment options was held between an open cerebrovascular neurosurgeon and a neurointerventional surgeon, and the decision was made to proceed with endovascular treatment using a PED flow diversion device.

Figure 1.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage due to rupture of a left ICA blister aneurysm.

Non-contrast head CT shows diffuse SAH in the basal cisterns (arrow, A). Left ICA DSA in the anteroposterior (B) and lateral projections (C) shows irregularity with an associated pseudoaneurysm (arrows, B and C) on the dorsal wall of the left ICA, which is consistent with a BA. Magnified DSA views in the anteroposterior (D) and lateral (E) projections better demonstrate the BA (arrows, D and E). Irregularity that is consistent with prior dissection (arrows, F and G) was also present in the right (F) and left (G) cervical internal carotid arteries on DSA, which suggests the presence of an underlying connective tissue disorder.

BA: blister aneurysm; CT: computed tomography; DSA: digital subtraction angiography; ICA: internal carotid artery; SAH: subarachnoid hemorrhage

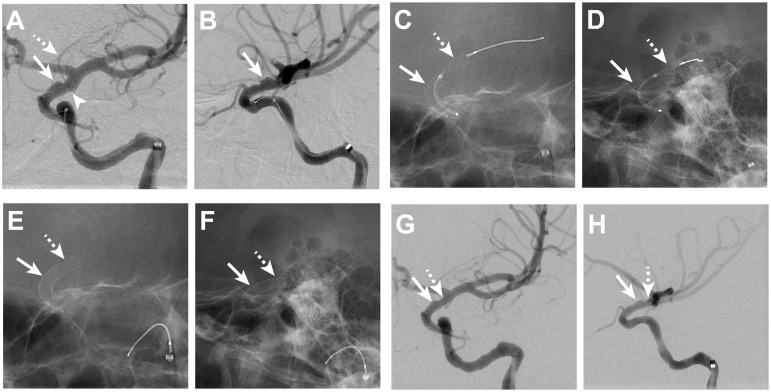

On DSA, the left ICA diameter proximal to the BA was 3.6 mm. There were two telescoping PEDs placed in the ICA across the BA. The distal aspect of the first PED (3.75 mm × 12 mm) was placed 2 mm distal to the edge of the BA and 1 mm proximal to the origin of the anterior choroidal artery (Figure 2). The second PED (3.75 mm × 10 mm) was placed 5 mm distal to the distal edge of the first PED (just proximal to the ICA terminus), and the proximal aspect of the second PED terminated within the first PED proximal to the BA (Figure 2). Dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin 81 mg and clopidogrel 75 mg daily) was initiated at the time of treatment with a 24-hour intravenous eptifibatide bridge.

Figure 2.

ICA blister aneurysm treatment with telescoping PED.

Left ICA DSA images from oblique anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) projections show the BA (arrows, A and B) arising from the dorsal wall of the left ICA. The distal aspect of the BA terminates at the aneurysm edge just proximal to the origin (arrowhead, A) of the left anterior choroidal artery (dashed arrow, A). Fluoroscopic images in oblique anteroposterior (C) and lateral (D) projections show the first PED (arrows, C and D) deployed across the BA while a second PED (dashed arrows, C and D) is being deployed distal to the termination of the first PED. The second PED (dashed arrows, E and F) terminates at the left ICA apex, which is 6 mm distal to the distal aspect of the first PED (arrow, E and F) after deployment. DSA following telescoping PED placement demonstrates persistent filling of the aneurysm (arrows, G and H); the distal most aspect of the telescoped PEDs is indicated by the dashed arrow (G, H).

BA: blister aneurysm; DSA: digital subtraction angiography; ICA: internal carotid artery; PED: pipeline embolization device

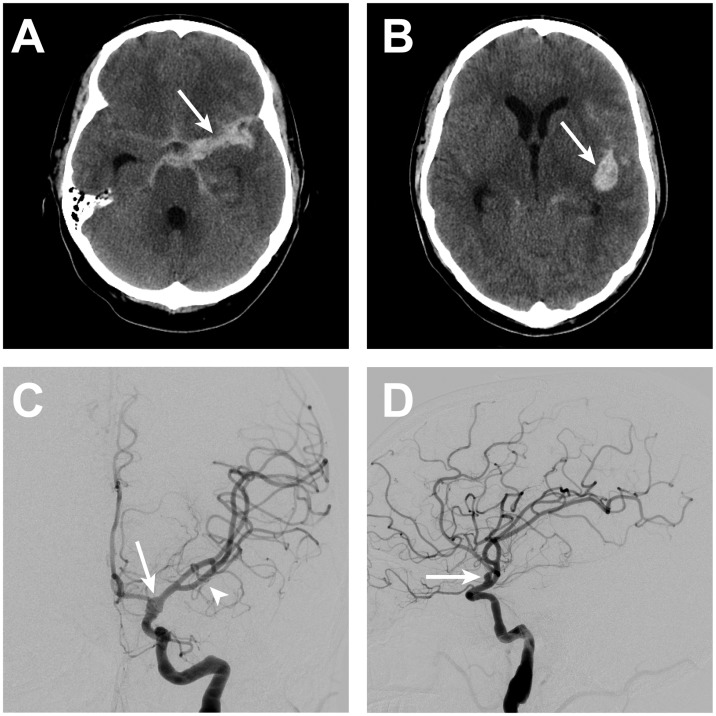

The patient initially did well, but he became unresponsive 5 days after treatment. A head CT showed new SAH (Figure 3). Antiplatelet medications were ceased, and platelets were administered. A second DSA revealed an increased diameter of the supraclinoid ICA, which measured 5.2 mm proximal to the BA, and increased BA size (Figure 3). The two PEDs had retracted by 6 mm, and there was increased growth of the BA. BA growth was felt to be due to either uncovering of the distal aspect of the ICA BA (Figure 4) or growth of the aneurysm despite flow diversion.

Figure 3.

ICA blister aneurysm re-rupture.

After 5 days from BA treatment with telescoping PED, the patient suffered aneurysm re-rupture that resulted in new SAH within the basal cisterns (arrow, A) and the left Sylvian fissure (arrow, B). Left ICA DSA in the anteroposterior (C) and lateral (D) projections demonstrated an increase in size of the left ICA blister aneurysm/pseudoaneurysm (arrows, C and D). Mass effect on the left middle cerebral artery vessels from the Sylvian fissure hemorrhage is apparent on the DSA with superior and medial displacement of these vessels (arrowhead, C).

BA: blister aneurysm; DSA: digital subtraction angiography; ICA: internal carotid artery; PED: pipeline embolization device; SAH: subarachnoid hemorrhage

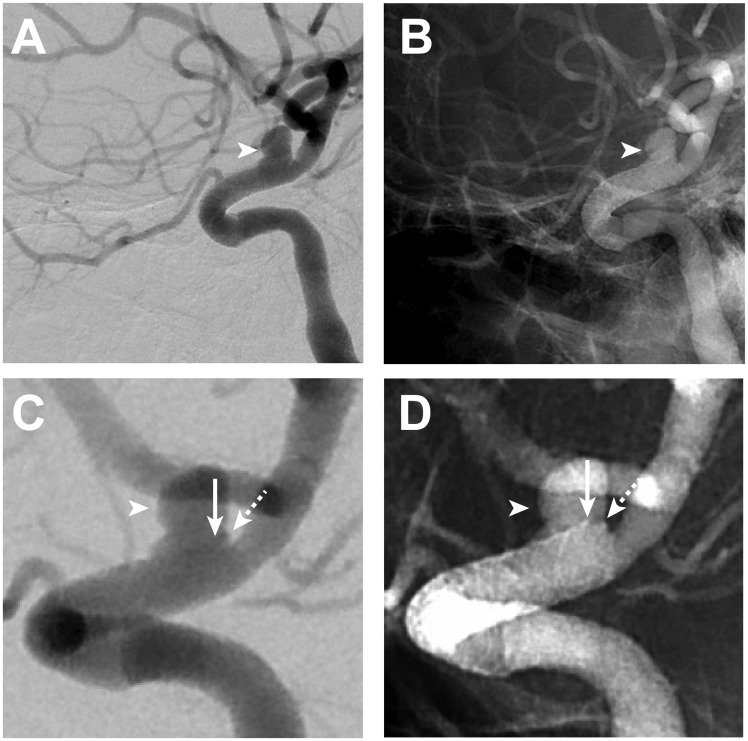

Figure 4.

ICA blister aneurysm growth after re-rupture.

All left ICA DSA images (A–D) are in an oblique lateral projection. Left ICA DSA performed after BA re-rupture (A–D) shows an interval increase in size of the left ICA blister aneurysm/pseudoaneurysm (arrowheads, A–D) compared with the left ICA DSA performed immediately after telescoping PED placement (see Figure 2). Magnified subtracted (C) and unsubtracted images (D) on the second DSA better demonstrate PED retraction and foreshortening by approximately 7 mm with the superior aspect of the distal PED construct. The PED is slightly obliqued on these views, such that the distal end of the PED projects with a portion of the distal edge of the PED located 1 mm proximal to the distal edge of the BA (arrows, C and D) and the other portion of the distal PED to be aligned with the distal end of the BA (dashed arrows, C and D).

BA: blister aneurysm; DSA: digital subtraction angiography; ICA: internal carotid artery; PED: pipeline embolization device

An additional multidisciplinary discussion was held to discuss treatment options, which included placement of additional flow diversion devices, parent vessel occlusion with associated direct left external carotid artery to left middle cerebral artery bypass, and open surgical wrapping. Parent vessel occlusion followed by immediate external carotid artery to middle cerebral artery bypass grafting was felt to be the best treatment option given the failed flow diversion treatment. The patient underwent a successful balloon test occlusion followed by endovascular parent vessel occlusion (Figure 5) for BA treatment. He was then transferred to the operating room, where an uncomplicated direct left external carotid artery to middle cerebral artery bypass surgery was performed to provide additional blood flow to the left anterior circulation in the event that the patient developed vasospasm.

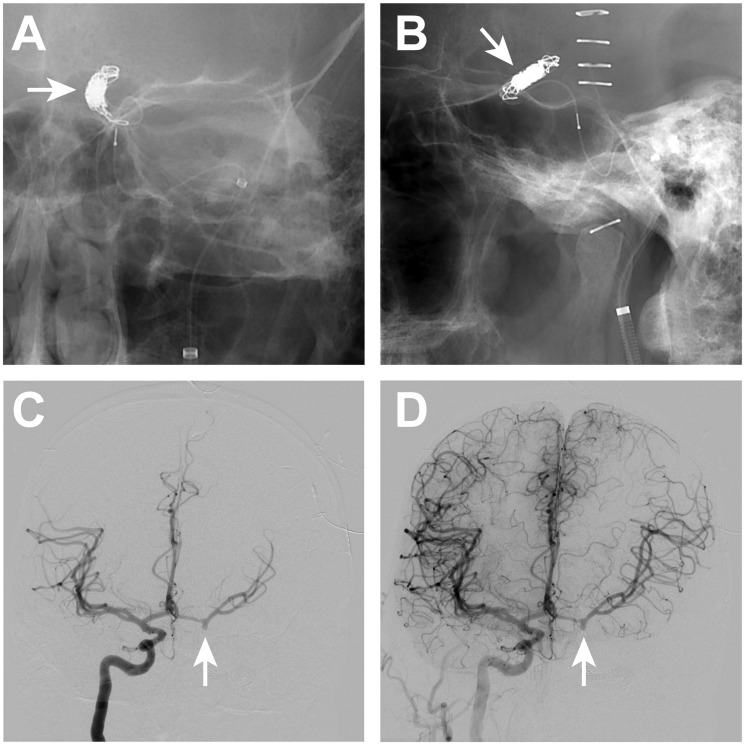

Figure 5.

Endovascular coil sacrifice of the left ICA for recurrent blister aneurysm treatment.

Endovascular occlusion of the supraclinoid left ICA within and just distal to the previously placed telescoping PEDs was performed following re-rupture of the left ICA BA. The coil mass (arrows, A and B) are present on anteroposterior and lateral radiographic images after occlusion. Right ICA DSA (C, D) performed after coil sacrifice of the left ICA shows robust filling of the left anterior circulation across a patent anterior communicating artery complex. There is filling of the distal left ICA to the margin of the coil mass (arrows, C and D) following right ICA DSA, but there no retrograde filling of the left ICA BA.

BA: blister aneurysm; DSA: digital subtraction angiography; ICA: internal carotid artery; PED: pipeline embolization device

The patient developed severe vasospasm 2 days after ICA coil sacrifice, which resulted in cerebral infarction despite aggressive endovascular treatment with intra-arterial nicardipine and cerebral angioplasty of the contralateral right supraclinoid ICA, A1 segment of the right anterior cerebral artery, and M1 segment of the right middle cerebral artery. The patient survived, but he was left with neurologic deficits that included both a receptive and expressive aphasia and right hemiplegia.

Discussion

BAs arise from the ICA or basilar artery. BAs are a rare cause of SAH and have high morbidity and mortality. BAs may be treated by surgical or endovascular techniques. Surgical BA treatment includes clipping, arterial wrapping, or aneurysm trapping with or without arterial bypass. Although some surgical series have shown favorable outcomes after surgical treatment, others have found high rates of intra-operative vessel rupture and poor outcomes.1

Endovascular BA treatments include deconstructive and reconstructive strategies. Deconstructive treatment is performed by parent vessel occlusion, and reconstructive approaches include primary coiling, stent-assisted coiling, or endovascular flow diversion.1–8 The PED is increasingly being used in an off-label manner for the treatment of ruptured cerebral aneurysms, and additional series have described PEDs for the treatment of ruptured BA.1,3–8

BA regrowth after PED treatment has been described on three prior occasions.8–10 In these prior reports, two right vertebral artery BAs and one ICA BA were treated with PEDs. Aneurysm regrowth was identified 5 days, 6 months, and 9 months after treatment, respectively.8–10 In these cases, no patient suffered a second SAH and BA regrowth was identified on during vasospasm treatment8 or routine follow up.9,10 The positioning of the PEDs in two of these cases was stable,9,10 and PED foreshortening was observed in a single vertebral artery BA.8 By contrast, our patient suffered a second SAH due to PED retraction 5 days after treatment. The cause of PED retraction is most likely due to the increased caliber of the parent ICA. However, the cause of this ICA caliber change is not clear. We postulate that there may have been a component of ICA vasospasm at the time of initial PED placement that led to the smaller diameter of this vessel. Moreover, it is likely that our patient likely had an underlying connective tissue disorder that may have resulted in changes in ICA vessel caliber following PED placement with associated foreshortening of the PED construct. Neurointerventionalists should be cognizant of the possibly dynamic nature of BA to ensure that these aneurysms remain adequately protected after endovascular treatment.

Conclusions

Our experience has implications for BA treatment with PED. First, caution is required when treating patients with a known or suspected underlying connective tissue disorder as the arteries in these patients may be prone to caliber changes that may significantly alter the positioning of PED after placement. Next, PED deployment should ensure a robust length on either side of the BA to prevent against aneurysm uncovering should the PED retract. Third, PED oversizing should be considered to ensure adequate anchoring in the event that the visualized vessel may be in vasospasm and artifactually narrowed at the time of treatment. Lastly, the rapidity with which the PED retracted and the BA re-grew in our patient and the prior demonstration of more delayed aneurysm recurrence suggests that frequent and close follow up imaging within 1–3 days may important to ensure BA obliteration. Future studies should further define the most optimal technique and follow up for BA treatment with a PED.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Szmuda T, Sloniewski P, Waszak PM, et al. Towards a new treatment paradigm for ruptured blood blister-like aneurysms of the internal carotid artery? A rapid systematic review. J Neurointerv Surg 2016; 8: 488–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rouchaud A, Brinjikji W, Cloft HJ, et al. Endovascular treatment of ruptured blister-like aneurysms: A systematic review and meta-analysis with focus on deconstructive versus reconstructive and flow-diverter treatments. Am J Neuroradiol 2015; 36: 2331–2339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nerva JD, Morton RP, Levitt MR, et al. Pipeline embolization device as primary treatment for blister aneurysms and iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms of the internal carotid artery. J Neurointerv Surg 2015; 7: 210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linfante I, Mayich M, Sonig A, et al. Flow diversion with pipeline embolic device as treatment of subarachnoid hemorrhage secondary to blister aneurysms: Dual-center experience and review of the literature. J Neurointerv Surg 2017; 9: 29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu YC, Chugh C, Mehta H, et al. Early angiographic occlusion of ruptured blister aneurysms of the internal carotid artery using the pipeline embolization device as a primary treatment option. J Neurointerv Surg 2014; 6: 740–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gong D, Yan B, Dowling R, et al. Successful treatment of growing basilar artery dissecting aneurysm by pipeline flow diversion embolization device. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2014; 23: 1713–1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Consoli A, Nappini S, Renieri L, et al. Treatment of two blood blister-like aneurysms with flow diverter stenting. J Neurointerv Surg 2012; 4: e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McTaggart RA, Santarelli JG, Marcellus ML, et al. Delayed retraction of the pipeline embolization device and corking failure: pitfalls of pipeline embolization device placement in the setting of a ruptured aneurysm. Neurosurgery 2013; 72(Suppl. 2 Operative): onsE245–E250. discussion onsE50–E51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerolus M, Kasliwal MK, Lopes DK. Persistent aneurysm growth following pipeline embolization device assisted coiling of a fusiform vertebral artery aneurysm: a word of caution!. Neurointervention 2015; 10: 28–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lang ST, Assis Z, Wong JH, et al. Rapid delayed growth of ruptured supraclinoid blister aneurysm after successful flow diverting stent treatment. J Neurointerv Surg. . Epub ahead of print 2016. DOI: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2016-012506.rep. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]