Abstract

Thrombosed giant aneurysm of the V1 segment of the vertebral artery is rare, and there is controversy regarding the optimal method of treatment in this portion. Here, we report a thrombosed giant aneurysm of the V1 segment of the vertebral artery with a good clinical course with endovascular proximal artery occlusion of the vertebral artery.

A 59-year-old woman presented with a large mass in the left side of the neck. Echographic examination revealed a mass measuring 42 × 38 × 48 mm in the left neck. Angiography showed a thrombosed giant aneurysm of the V1 segment of the left vertebral artery. Endovascular proximal artery occlusion of the vertebral artery was performed, and the aneurysm lessened gradually. Although a number of procedures have been developed to treat extracranial vertebral artery aneurysms, endovascular proximal artery occlusion is a good option to treat aneurysms in this portion.

Keywords: Endovascular treatment, giant aneurysm, vertebral artery

Introduction

Extracranial vertebral artery aneurysms are rare,1 with most cases being caused by trauma.2 Other etiologies are rare and varied, and include atherosclerosis, vasculitis,3 and connective tissue diseases.4 Although there have been reports of treatment by bypass surgery and ligation of the vertebral artery5 as well as endovascular procedures,6 there are as yet no established procedures for the treatment of aneurysms arising in this portion of the vertebral artery.

Here, we describe a case of a thrombosed giant V1 segment of the vertebral artery treated successfully by endovascular proximal artery occlusion of the vertebral artery.

Case presentation

A 59-year-old woman without any relevant medical or traumatic history visited our hospital due to swelling in the left anterior neck. Echographic examination showed a mass measuring 42 × 38 × 48 mm in the left lower neck. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a thrombosed giant aneurysm in the left neck (Figure 1). A diagnosis of extracranial vertebral artery aneurysm was made. She had no serological abnormalities. Left subclavian angiography showed a fusiform aneurysm located in the V1 segment of the left vertebral artery (Figure 2(a)). The vertebral artery structure was normal at the proximal site of the aneurysm. After confirming tolerance by balloon test occlusion, this aneurysm was treated by endovascular proximal artery occlusion.

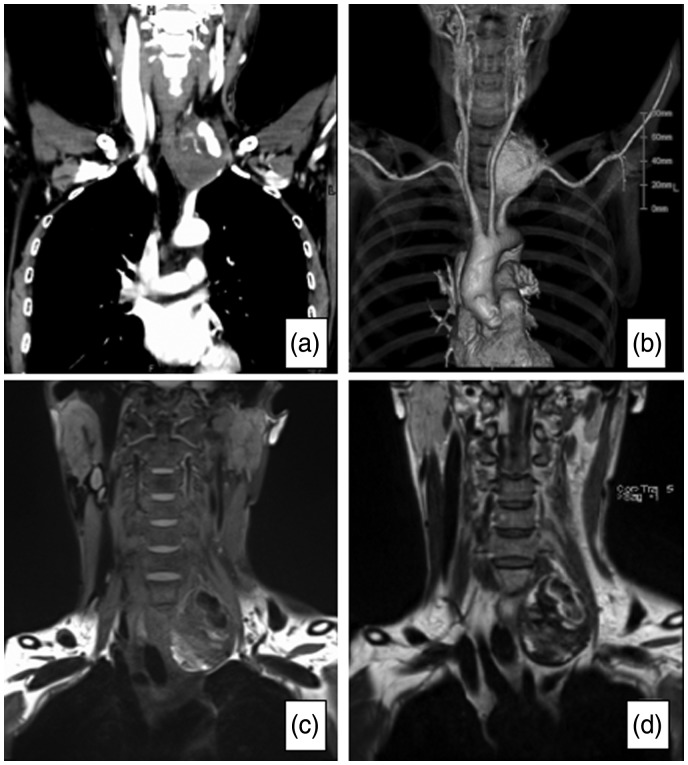

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced CT (a) and 3D CTA (b) showing a thrombosed aneurysm of the V1 segment of left vertebral artery. Coronal MRI T1WI (c) and T2WI (d) showing a 42 × 39 × 48 mm thrombosed aneurysm at the left lower neck.

CT: computed tomography; CTA: computed tomography angiography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging

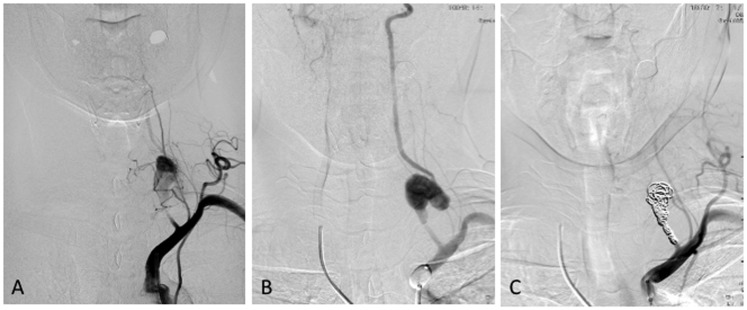

Figure 2.

(a) Left subclavian angiogram showing the giant aneurysm of the V1 segment and normal structure of vertebral artery at proximal site of the V1 segment. The aneurysm was filled with contrast agent partially. (b) Right vertebral angiogram with the occlusion of the left subclavian artery. (c) Left subclavian angiogram showing complete obliteration of the aneurysm.

The procedure was performed under local anesthesia. A 6F balloon-guiding catheter (Cello; Medtronic, Irvine, CA, USA) was placed in the proximal segment of the left subclavian artery, and a microcatheter (SL10; Striker, Natick, MA, USA) was positioned in the proximal site of the aneurysm. Keeping the balloon-guiding catheter inflated, the internal space of the proximal site of the aneurysm was embolized with coils (Axium; Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland) (Figure 2). The balloon-guiding catheter was deflated after confirming obliteration of the aneurysm by right-side vertebral angiography.

The patient was discharged 1 week after treatment without neurological deficits. A month after treatment, echographic examination showed the ‘to and fro’ image in the aneurysm. However, this had disappeared on the examination 2 months later. MRI showed that the aneurysm gradually decreased in size (Figure 3).

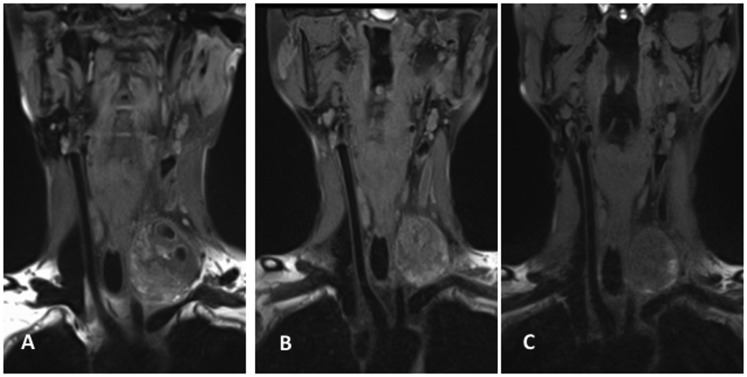

Figure 3.

Coronal MR T1WI showing the reduction of aneurysm size. (a) Pretreatment, (b) 1 year after treatment, (c) 2 years after treatment.

MR: magnetic resonance

Discussion

We described a rare case of vertebral V1 segment thrombosed giant aneurysm that was treated successfully with proximal occlusion by endovascular treatment. The main point of interest of this case is the method used for treatment for thrombosed giant aneurysm located in the V1 segment of the vertebral artery.

Rupture of this part of the aneurysm can be fatal due to sudden obstruction of airway occlusion and intrathoracic bleeding, because the origin of the vertebral artery lies in the thoracic cavity. There are two choice of treatment in such cases (i.e. direct surgery and interventional radiology; IVR). Occlusion test of the affected side must be performed. In cases without tolerance to occlusion, a revascularization procedure is required prior to occlusion. For cases in which the aneurysm is located at the origin of the vertebral artery, the procedure could be more invasive, because direct surgery requires thoracotomy. To approach the origin of the left subclavian artery, it is necessary to get off the clavicle and first rib, and the upper site of median sternotomy is needed to open the thoracic cavity.7 Direct surgery is invasive with a high risk of postoperative complications. In contrast, IVR was less invasive in this case, when the normal structure of vertebral artery remains at the proximal site of the fusiform aneurysm. The treatment procedure could consist of proximal occlusion or distal and proximal occlusion (i.e. internal trapping). In this case, the internal cavity of the aneurysm was thrombosed, there was a risk of distal embolic complications. Therefore, we planned proximal occlusion. Furthermore, the aneurysm was large, and a large mass of the coil could be left in the neck if treated with internal trapping.

Aneurysms in the internal carotid artery (IC) cavernous portion might be similar situation, because of difficulty to treat with direct surgery. In general, such aneurysms are treated with proximal occlusion when treated by direct surgery.8,9 The backward vascular flow of the distal site may prevent occlusion of the aneurysm. In the present case, the preoperative occlusion test showed that backward flow from the distal site was weak when the proximal site of the V1 segment was occluded. In addition, the aneurysm became the terminal end of the collateral flow, and the flow could be stagnant and thrombus formation was established. Finally, the aneurysm was occluded completely.

Extracranial vertebral artery aneurysms are very rare because of their anatomical structure. The most common etiology is trauma,2 while others include hereditary diseases, such as Ehler–Danlos syndrome,4,5 vasculitis,3 and arteriosclerosis. Our patient had no previous history of illness or trauma, and serological examination did not indicate any abnormalities. She complained only of a mass in the left neck. However, a few reports indicated that some patients complain of radiculopathy10 and dysphasia11 because the enlarged aneurysms compress the brachial plexus and laryngeal recurrent nerve, which run close to the dorsal part of the V1 segment. The aneurysm in our patients was large, and we chose proximal occlusion as an effective procedure to reduce the mass effect from the long-term viewpoint.

This case showed that proximal occlusion can be an effective procedure in cases in which the normal structure of the vertebral artery is maintained at the proximal site.

Conclusion

We reported a rare case of thrombosed giant aneurysm of the extracranial vertebral artery. In this case the aneurysm was fusiform of the V1 segment and the structure of the vertebral artery at the proximal site was normal. Therefore, we chose endovascular treatment (i.e. proximal occlusion). After the operation, the patient was followed up for 2 years with no signs of recurrence, and the aneurysm has gradually decreased in size. This case demonstrates that the endovascular proximal occlusion procedure can be effective in cases of thrombosed giant aneurysm in this segment of the vertebral artery.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Hiramatsu H, Matsui S, Yamashita S, et al. Ruptured extracranial vertebral artery aneurysm associated with neurofibromatosis type 1. Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2012; 52: 446–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foreman PM, Griessenauer CJ, Falola M, et al. Extracranial traumatic aneurysms due to blunt cerebrovascular injury. J Neurosurg 2014; 120: 1437–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao S, Rao S, Dhindsa-Castanedo L, et al. Rapidly evolving large extracranial vertebral artery pseudoaneurysm in Behçet's disease: Case report and review of the literature. Mod Rheumatol 2015; 25: 476–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sultan S, Morasch M, Colgan MP, et al. Operative and endovascular management of extracranial vertebral artery aneurysm in Ehlers–Danlos syndrome: A clinical dilemma-case report and literature review. Vasc Endovascular Surg 2002; 36: 389–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morasch MD, Phade SV, Naughton P, et al. Primary extracranial vertebral artery aneurysms. Ann Vasc Surg 2013; 27: 418–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shang EK, Fairman RM, Foley PJ, et al. Endovascular treatment of a symptomatic extracranial vertebral artery aneurysm. J Vasc Surg 2013; 58: 1391–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morimoto K, Matsuda H, Fukuda T, et al. Hybrid repair of proximal subclavian artery aneurysm. Ann Vasc Dis 2015; 8: 87–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohtaki S, Mikami T, Iihoshi S, et al. [Strategy for the treatment of large-giant aneurysms in the cavernous portion of the internal carotid artery]. No Shinkei Geka 2013; 41: 107–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elhammady MS, Wolfe SQ, Farhat H, et al. Carotid artery sacrifice for unclippable and uncoilable aneurysms: Endovascular occlusion vs common carotid artery ligation. Neurosurg 2010; 67: 1431–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peyre M, Ozanne A, Bhangoo R, et al. Pseudotumoral presentation of a cervical extracranial vertebral artery aneurysm in neurofibromatosis type 1: case report. Neurosurg 2007; 61: e658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ota N, Tanikawa R, Eda H, et al. Radical treatment for bilateral vertebral artery dissecting aneurysms by reconstruction of the vertebral artery. J Neurosurg 2016; 125: 953–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]