Abstract

Background

Latinas are disproportionately affected by perinatal depression (PND) as well as by adverse life events (ALEs), an independent predictor of PND. Dysregulation of the hypothalamic-adrenal-pituitary (HPA) axis has been seen both in women with PND and with a history of ALEs in non-Latinas. Though some evidence suggests that HPA axis dysregulation may mediate the link between ALEs and PND, this has received little attention and there are no studies that have examined these pathways in Latinas. The primary aim of the present study was to explore, in a Latina sample, associations between ALEs, PND, and HPA axis stress reactivity to a physical stressor-the cold pressor test (CPT). The secondary aim was to explore whether HPA axis reactivity and PND were associated with pain sensitivity to the CPT.

Methods

Thirty-four Latinas were enrolled in their third trimester of pregnancy and interviewed at 4 and 8 weeks postpartum. Depression status was determined using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (≥ 10). At 8 weeks postpartum, 27 women underwent laboratory-induced pain testing using the cold pressor test (CPT). Plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and cortisol (CORT) were sampled pre- and post-CPT to generate a stress reactivity score (post-pre). Pain sensitivity and ALEs were also assessed.

Results

At enrollment, 26% of women were depressed and 18% were depressed at 8 weeks postpartum. Forty-eight percent reported at least one childhood ALE. There was a significant and positive association between any childhood ALE and prenatal depression scores (p = 0.025). Infant-related ALEs were significantly associated with greater ACTH reactivity to the CPT (p = 0.030). Women with a history of any childhood ALE exhibited a blunted CORT response to the CPT (p = 0.045). Women with a history of PND at 4 weeks had greater ACTH stress reactivity to the CPT (p = 0.027). No significant effects of PND were seen for pain sensitivity measures in response to the CPT, though there was a positive and significant correlation between pain tolerance and CORT response to the CPT in the whole sample.

Conclusions

Given the associations between ALEs and PND and their individual effect on HPA axis stress reactivity, future studies on perinatal depression should include a larger sample of Latinas to test mediating effects of HPA axis reactivity on associations between ALEs and PND.

Keywords: Latina, adverse life events, HPA axis, perinatal depression, pain sensitivity

Introduction

Latinos are the prevailing ethnic minority group in the United States (Census, 2013). With the highest fertility rate in the U.S. (Passel, 2013), Latinas accounted for 24% of live births in 2010, with 56% of those being from immigrant women (Livingston & Cohn, 2012). Given this population’s rate of growth, research regarding prenatal and postpartum depression (PPD), also referred to as perinatal depression, is essential (Lara-Cinisomo, Wisner, & Meltzer-Brody, 2015). Latinas suffer high rates of perinatal depression compared to non-Latinas yet there has been little research designed to understand the risk factors or pathophysiology that might contribute to this increased risk.

Perinatal depression (PND) is characterized as a major depressive episode occurring in pregnancy or in the first postpartum year (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Gavin et al., 2005). While PND is seen in up to 12–19% of women in the general population (Gavin et al., 2005), the occurrence of PND in Latinas living in the US has been estimated at 30–53% (Ceballos, Wallace, & Goodwin, 2016; Kieffer et al., 2013; Kuo et al., 2004; Lucero, Beckstrand, Callister, & Sanchez Birkhead, 2012; Mukherjee, Trepka, Pierre-Victor, Bahelah, & Avent, 2016; Zayas, Jankowski, & McKee, 2003). Although the causes of perinatal depression remain elusive, adverse life events (ALEs), such as childhood abuse and intimate partner violence, are potent risk factors for perinatal depression (Alvarez-Segura et al., 2014; Buist & Janson, 2001; Faisal-Cury, Menezes, d’Oliveira, Schraiber, & Lopes, 2013; Meltzer-Brody et al., 2013; Plaza et al., 2012; Rodríguez et al., 2010).

There is growing evidence that exposure to ALEs, including those in early life, can lead to long-term dysregulation in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis response to stress (Heim, Newport, Mletzko, Miller, & Nemeroff, 2008; Klaassens et al., 2009; Shea, Walsh, MacMillan, & Steiner, 2005), and this dysregulation may manifest as either a blunted or exaggerated stress response (McEwen, 1998). Briefly, in response to a perceived stressor, the hypothalamus releases corticotropic-releasing hormone (CRH), which then triggers the anterior pituitary to secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) into the blood stream (Tsigos & Chrousos, 2002). The adrenal cortex is subsequently stimulated by ACTH to produce and release cortisol. Activation of the HPA axis is tempered by a negative feedback loop, which involves cortisol suppressing the further release of CRH and ACTH by binding to glucocorticoid receptors in the hypothalamus and pituitary gland (Blume, Douglas, & Evans, 2011). This negative feedback loop reestablishes homeostasis to ultimately regulate cortisol release in response to stress.

Dysregulation in the HPA axis has been implicated in PND (Bloch, Daly, & Rubinow, 2003; E. Q. Cox et al., 2015; de Rezende et al., 2016; Glynn, Davis, & Sandman, 2013; Groer & Morgan, 2007; Magiakou et al., 1996; Parry et al., 2003; Yim, Tanner Stapleton, Guardino, Hahn-Holbrook, & Dunkel Schetter, 2015). For example, Jolley et al. showed that at 6 and 12 weeks postpartum, women with depression had higher ACTH levels and lower CORT levels compared to nondepressed postpartum women during physical stress testing (Jolley, Elmore, Barnard, & Carr, 2007). Although the research on the association of ALEs to HPA axis function during the perinatal period is extremely limited to date, one study found that perinatal women with histories of childhood ALEs exhibited HPA axis dysregulation. Results showed that mothers with histories of childhood abuse had lower CORT reactivity to a psychosocial and physical stressor during the postpartum period (Brand et al., 2010). Results also showed, however, that current maternal depressive symptoms, recent stressful events, and a history of PTSD moderated the effects of childhood ALEs on CORT reactivity to the stressors (Brand et al., 2010).

Latinas in the U.S. and abroad are at substantially greater risk of experiencing ALEs due to poverty, discrimination, and lifetime histories of abuse (Garcia-Esteve et al., 2014; Kuo et al., 2004; Lucero et al., 2012) and as noted previously are at substantially greater risk to develop PND. Nonetheless, few studies have examined the association between ALEs and perinatal depression in Latinas and none has investigated the role that HPA axis dysregulation may play in the elevated risk for perinatal depression seen in Latinas. Previously, we developed a conceptual model of risk for postpartum depression in Latinas that hypothesized HPA axis dysregulation may serve as a pathophysiological mediator of risk linking ALEs to vulnerability to develop depression in the perinatal period (Lara-Cinisomo, Girdler, Grewen, & Meltzer-Brody, 2016). Consequently, the primary aim of this exploratory study was to examine univariate relationships between ALEs, PND, and HPA axis stress reactivity to a physical stressor – the hand cold pressor test (CPT) in a sample of Latinas during the perinatal period.

A secondary aim of the study was to explore whether HPA axis responses to the CPT predicted sensitivity to that test. While the CPT activates stress-responsive axes, including the HPA and sympathetic nervous system axes (Godfrey et al., 2014; Santa Ana et al., 2006; Schwabe, Haddad, & Schachinger, 2008), and is commonly used as a physical stressor in laboratory studies, it is also a potent noxious stimulus (Girdler et al., 2005; Gordon, Johnson, Nau, Mechlin, & Girdler, 2017; Light et al., 1999). Consistent with a stress-induced, endogenous pain regulatory mechanism (Choi, Chung, & Lee, 2012; Geva, Pruessner, & Defrin, 2014; Hannibal & Bishop, 2014; Paananen et al., 2015), studies in non-clinical samples generally find a positive correlation between cortisol levels and tolerance to noxious stimuli, including the CPT (Mechlin, Maixner, Light, Fisher, & Girdler, 2005; Sudhaus et al., 2015). Additionally, reduced diurnal variation of cortisol, a reflection of HPA axis dysregulation, is correlated with increased pain sensitivity in response to the CPT (Godfrey et al., 2014).

It is well established that clinical pain and somatic symptoms are associated features of depression (Corruble & Guelfi, 2000; Simon, VonKorff, Piccinelli, Fullerton, & Ormel, 1999). While 30–77% of women experience pain following childbirth (Fitzgerald, 2013), problematic and persistent pain can increase a woman’s risk for PND. Recent evidence suggests that problematic postpartum pain (e.g., vaginal, cesarean, back, etc.) and PND occur together at higher-than-expected rates (Bair, Robinson, Katon, & Kroenke, 2003). Within the perinatal period, pain sensitivity is an important factor to consider in women with respect to understanding perinatal mood disturbance because heightened pain sensitivity, particularly related to breastfeeding, has also been implicated in premature weaning (Indraccolo, Bracalente, Di Iorio, & Indraccolo, 2012), which has itself been associated with PPD (Hatton et al., 2005). The possibility exists that dysregulation in the HPA axis response to stress represents a potential shared mechanism linking depression, including perinatal depression, to heightened pain sensitivity. This is supported, in part, by studies showing that elevated depressive symptoms are associated with attenuated CORT response to psychological stress (Burke, Davis, Otte, & Mohr, 2005).

To address our study aims, we examined relationships between PND assessed longitudinally from third trimester of pregnancy to 4 and 8 weeks postpartum, and the relationship of depression to ALEs, as well as to HPA axis stress reactivity and sensitivity to the CPT assessed at 8 weeks postpartum. The primary objective of this exploratory, laboratory-based study was to examine evidence for associations between ALEs, HPA axis response to physical stress and PND in Latinas. The secondary aim was to assess whether there was evidence for HPA-axis endogenous pain regulation of sensitivity to the CPT and whether there were differences by PND status. The results of this study are intended to generate mediational hypotheses to test in a larger sample of Latinas.

Material and Methods

Sixty-five prospective participants were screened during routine prenatal visits at a local hospital and nearby community centers by trained English- and Spanish-speaking female research assistants (RA) and 34 were enrolled. To be eligible to participate, women had to self-identify as Latinas; have a singleton pregnancy; be able to read, write, and speak English or Spanish; and be willing to be followed until eight weeks postpartum. This exploratory study was conducted within the context of a larger program of research involving a birth cohort of Latinas - the Study of Exposure to stress, Postpartum mood, Adverse life events, and Hormonal function among Latinas (SEPAH Latina). Because one of the primary aims of SEPAH Latina was to examine breastfeeding practices, oxytocin mechanisms and PND (results reported elsewhere –(Lara-Cinisomo, Plott, Grewen, & Meltzer-Brody, 2016; Lara-Cinisomo, McKenney, Di Florio, & Meltzer-Brody, in press), we intentionally recruited women who intended to breastfeed ≥2 months. Exclusion criteria included reported maternal or infant disorder that might interfere with breastfeeding, maternal substance use, and current or past severe psychiatric disorder other than unipolar depression or anxiety (e.g., bipolar disorder).

The study was approved by the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board. Women gave written consent prior to enrollment and were compensated after each interview. For this study, women were assessed three times: 1) in the third trimester of pregnancy during the enrollment session where demographic information was collected; 2) at four weeks postpartum via phone interview; and 3) at eight weeks postpartum during a laboratory visit.

Measures

Perinatal Depression

Depression status was assessed at each time point using the English- and Spanish validated Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS; (J. L. Cox, Holden, & Sagovsky, 1987; L. s. Garcia-Esteve, Ascaso, Ojuel, & Navarro, 2003). The EPDS is a 10-item instrument widely used to assess depression post-delivery and has also been shown to be valid during the prenatal period (Kozinszky & Dudas, 2015). Responses are based on a 4-point scale (0, 1, 2, and 3) and responses are summed to produce a total score, with a maximum score of 30. Depression was operationally defined using the cutoff for minor and major depression (EPDS ≥10; (J. L. Cox, Chapman, Murray, & Jones, 1996; Gaynes et al., 2005), which has been shown to be a reliable cut point for Latinas (Howell et al., 2012). The Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID) (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1997) was used at enrollment to collect depression histories.

Adverse life events

Adverse life events were ascertained at enrollment using the SCID, which captures childhood and adult-related ALEs as well as infant-related adversity such as loss of an infant and premature birth, and intimate partner violence. Additionally, a trained RA or the Principal Investigator administered a structured ALEs interview at 8 weeks postpartum. This interview captured childhood abuse, including sexual and physical abuse, as well as other ALEs before 18 years of age (J. Leserman et al., 1997; Jane Leserman et al., 2007). This instrument has been shown to reliably assess ALEs and to be associated with PND (Pedersen et al., 2016).

Physical Stressor, pain assessment and collection of biomarkers

At 8 weeks postpartum, women were invited to the hospital where they participated in a controlled laboratory experiment that began at 9:00 a.m. for all participants. As part of the larger aims of the SEPAH Latina study, women were instructed to allow for at least a 90-minute window between the at-home morning feeding and the scheduled laboratory visit to ensure the child would be hungry during an observed feeding session. The laboratory protocol was modeled after a recent prospective study of PPD, lactation and neuroendocrine function in non-Latina women (Stuebe, Grewen, & Meltzer-Brody, 2013) and extended this work to include HPA axis modulation of pain sensitivity. Participants were seated in a comfortable chair where a trained nurse placed an intravenous (IV) catheter in an antecubital vein; the IV remained in place for the duration of the laboratory experiments and the nurse remained in the room, behind a curtain during the entire laboratory protocol. Participants remained in the chair and read home improvement magazines for the 10-minute habituation period. The first condition involved an infant feeding session where women were asked to either breast- or bottle-feed their infant for at least 10 minutes (results reported elsewhere; Lara-Cinisomo et al., in press).

Plasma ACTH and serum CORT were collected via IV by a trained nurse 10 minutes following the infant feeding session and these levels constituted the pre-stressor rest levels for the current report. After a ten-minute rest, women participated in the CPT to assess pain sensitivity and HPA axis function. The CPT is one of the most frequently used procedures to measure pain sensitivity in a laboratory setting (Koenig et al., 2014; McGinley & Friedman, 2015). Participants submerge their hand in ice water, eliciting a strong sympathetic nervous system stress response and activation of the HPA axis. To maximally activate the HPA axis, participants were video-recorded using a video camera propped on a tripod in front of them (Schwabe et al., 2008). Participants submerged their hand in a container filled with ice and water set at 3.5°C (38.5°F) and maintained at that temperature using a water-circulating device. To prevent tissue damage, a maximum time limit of 5 minutes was imposed. Participants were instructed to report when the sensations in their hand first became painful, allowing us to determine pain threshold measured in seconds and when they were no longer willing or able to tolerate the pain to capture pain tolerance measured in seconds. The RA showed a visual analog scale (VAS) that ranged from 0 “No pain intensity” to 100 “Strongest imaginable pain intensity of any kind” to the women and asked them to verbally rate pain intensity before removing their hands from the ice bath. Participants also verbally reported levels of pain unpleasantness using a VAS ranging from 0 “No unpleasantness” to 100 “Most unpleasant pain of any kind imaginable.” The RA recorded participant ratings using pencil/pen on the laboratory protocol sheet. Plasma ACTH pg/ml and serum CORT ug/dl were collected again 20 minutes after the onset of the CPT stressor. This time point was selected based on the consistent evidence that CORT peaks within 10–30 minutes following stress onset (Arvat et al., 2000; S. M. Smith & Vale, 2006).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed to characterize the sample. Logistic regressions were conducted to test the probability of prenatal depression predicting current postpartum depression. Fisher’s exact tests were conducted to assess associations between categorical variables, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were conducted to determine associations between categorical predictors (e.g., any childhood ALE coded as yes/no) and continuous outcomes (e.g., ACTH, depression scores). Pearson correlations were conducted to assess the association between pain measures and hormone levels. We conducted correlations and ANOVAs to assess associations between ALEs and neuroendocrine function. We used ANOVA to explore reactivity in ACTH and CORT to the CPT in the entire sample, by depression status, and by type of ALE. HPA stress reactivity was defined as post-CPT ACTH or CORT concentration minus baseline, pre-CPT concentrations. Where significant differences in reactivity emerged, paired t-tests were conducted to examine the source of the difference. Given the skewedness of plasma ACTH levels in the sample, the log of ACTH is used in our analysis. Although multiple tests were conducted in this exploratory study, we did not control for Type 1 error rate because of the pilot nature of the research. P-values less 0.05 were interpreted as significant. Due to the limited sample size, these models did not control for any other participant characteristics. All comparisons among means are thus performed without any a priori expectation, therefore no adjustment for multiple significant testing was employed (Bender & Lange, 2001). All of the analyses were conducted using SPSS 23 (IBM_Corp., 2015).

Neuroendocrine Assays

ACTH Radioimmunoassay

Plasma ACTH levels were measured using a commercially available double antibody radioimmunoassay kit and protocol available from MPBiomedicals, Orangeburg, NY. Samples do not require extraction. Samples were incubated with anti-ACTH and hACTH-125I at 4°C for 24 hours. Following a brief incubation with a second antibody precipitating reagent, the 125I-ACTH bound to the antibody complex were separated from free by a 40-minute centrifugation at 1700xg. Radioactivity in the pellet was measured using a Perkin Elmer 1470 Wizard gammacounter, which calculates the pg/ml content of ACTH in each sample from the standard curve. The ACTH assay has a sensitivity of 5.7 pg/ml with a standard range of 10 to 1000pg/ml. The intra- and inter- assay variation is 4.1% and 3.9%, respectively.

Cortisol Radioimmunoassay

Serum cortisol levels were assessed using a commercially available coated tube radioimmunoassay kit and protocol from MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH. The cortisol assay has a sensitivity of .07 ug/dl with a standard range of 1 to 60 ug/dl. The intra- and inter-assay variation is 4.7 and 7.6%, respectively.

Results

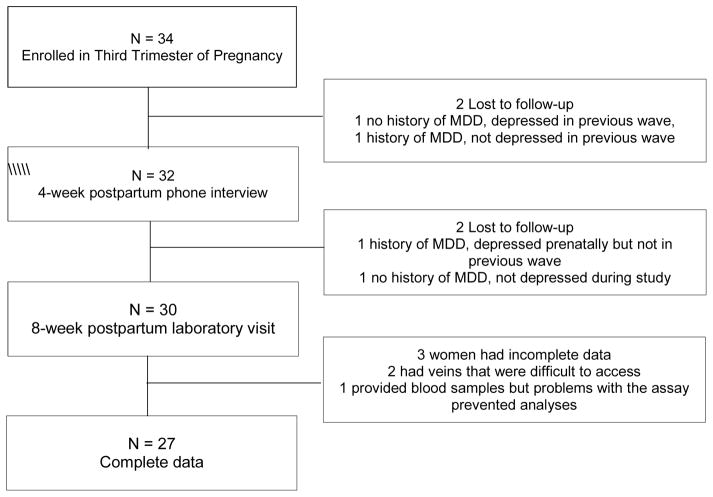

As Figure 1 shows, 34 women were enrolled, two women were lost to follow-up at 4 weeks and two were lost prior to the 8-week postpartum laboratory visit. Of the four lost to follow-up, one woman had PND at enrollment. Thirty women attended the laboratory visit at 8 weeks postpartum. Two nondepressed women had difficult-to-access veins, which prohibited us from drawing blood. Of the 28 whose blood was drawn, one sample was excluded from the hormone analyses because there were extraction issues during assaying; this woman had PND. Because the focus of this report is on the univariate relationships involving PND, ALEs, hormones, and pain sensitivity, all analyses were restricted to these 27 women with complete data.

Figure 1.

Participant flow chart

Of the 27 women with complete data, 82% percent were Spanish speaking and 85% were immigrant. More than three quarters were married or cohabitating (85%) and most were multiparous (63%). At enrollment, seven of the 27 women (26%) met the cutoff for minor or major depression (EPDS ≥10); five women met the criteria at 4 weeks postpartum (18%) and five women met the criteria at 8 weeks postpartum (18%). According to the SCID, more than half (56%) had a history of major depression and 15% of those had a history of postpartum onset. Results from the logistic regressions indicate that prenatal depression determined at enrollment using the EPDS was significantly predictive of PND at 4 weeks and 8 weeks (β = 3.23, p = 0.012, respectively). Depression at 4 weeks was also predictive of PND at 8 weeks (β = 4.43, p = 0.003). There was a marginally significant association between depression history based on the SCID and prenatal depression (β = −1.87, p = 0.058), but none with depression at 4 weeks (β = 0.000, p = 1.000) or 8 weeks (β = −1.03, p = 0.318).

Perinatal Depression and Adverse Life Events (ALEs)

Fourteen of the 27 women (52%) reported at least one childhood ALE. Physical abuse was the most commonly reported type of childhood ALE (n = 7), followed by sexual abuse (n = 6), and childhood verbal abuse (n = 4). Four women reported death of a parent and two experienced parent abandonment prior to the age of 18. With regard to adulthood ALEs, seven women reported a history of intimate partner violence (IPV) and four women reported infant-related adversity experienced in adulthood (e.g., infant demise). With regard to lifetime ALEs, five women reported more than one form of childhood and adulthood abuse.

As summarized in Table 1, women who reported at least one form of childhood ALE had, on average, higher mean EPDS depression scores over the three assessment periods (pre-, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks postpartum). However, the relationship between a history of childhood ALEs and greater depressive symptomatology was greatest for prenatal depression scores (F (1, 25) = 5.69, p = 0.025). A marginally significant association for depression scores at 8 weeks postpartum was found (F (1, 25) = 3.35, p = 0.08), while a history of childhood abuse did not predict depression symptom scores at 4 weeks postpartum (F (1, 25) = 0.001, p = 0.974). A similar pattern was observed among women who reported at least one infant-related ALEs and PND, though no significant associations were observed.

Table 1.

Adverse Life Events (ALE) by Mean Perinatal Depression Score based on the EPDS (Standard Deviations reported in parenthesis) (n = 27).

| Prenatal depression score | 4 week postpartum depression score | 8 week postpartum depression score | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any Childhood ALE | |||

| No (n = 13) | 3.92 (3.28) | 5.08 (4.59) | 2.85 (3.85) |

| Yes (n = 14) | 7.86 (5.04)* | 5.14 (5.84) | 6.00 (4.98) |

| Any Adulthood ALE | |||

| No (n = 21) | 6.57 (5.03) | 5.90 (5.38) | 5.00 (5.04) |

| Yes (n = 6) | 3.83 (2.14) | 2.33 (3.39) | 2.67 (2.58) |

| Any infant-related ALE | |||

| No (n = 23) | 5.57 (4.18) | 4.57 (4.60) | 4.30 (4.87) |

| Yes (n = 4) | 8.25 (7.18) | 8.25 (7.85) | 5.50 (3.70) |

| Total (N = 27) | 5.96 (4.65) | 5.11 (5.18) | 4.48 (4.67) |

Notes:

p < 0.05

HPA axis response to the CPT

There was a significant positive correlation between ACTH reactivity (post ACTH – pre ACTH) (r = 0.98, p = 0.000, not shown) and CORT reactivity to the CPT (post CORT – pre CORT) (r = 0.71, p = 0.000, not shown). As Table 2 shows, the mean pre-CPT ACTH levels of 4.49 (SD = 0.51) and the mean post-CPT levels of 4.47 (SD = 0.57), indicate no ACTH response to the CPT in the sample as a whole (t (26) = 1.22, p= 0.233). In the sample as a whole, the mean pre-CPT CORT levels was 8.13 (SD = 5.13) and the post-CPT CORT levels was 8.53 (SD = 6.47), a difference that was not statistically significant in the sample as a whole (t (26) = −0.46, p = 0.652).

Table 2.

Mean (+SEM) HPA axis measures at baseline and in response to CPT by depression status (n=27)

| Prenatal Depressed (n = 7) | Prenatal Nondepressed (n = 20) | 4 weeks Postpartum Depressed (n = 5) | 4 weeks Postpartum Nondepressed (n = 22) | 8 weeks Postpartum Depressed (n = 5) | 8 weeks Postpartum Nondepressed (n = 22) | All women at 8 weeks Postpartum (n = 27) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LogACTH (pg/ml) | |||||||

| Pre-CPT | 4.68 (0.36) | 4.43 (0.06) | 4.87 (0.48) | 4.41 (0.05) | 4.96 (0.45) | 4.39 (0.06) | 4.49 (0.10) |

| Post-CPT | 4.72 (0.39) | 4.37 (0.06) | 4.94 (0.53) | 4.36 (0.05) | 4.99 (0.51) | 4.35 (0.05) | 4.47 (0.11) |

| Reactivity to CPT | 0.042 (0.05) | −0.052 (0.02) | 0.08 (0.07)a | −0.05 (0.02) | 0.03 (0.07) | −0.04 (0.02) | −0.03 (0.02) |

| Cortisol (ug/dL) | |||||||

| Pre-CPT | 9.49 (2.87) | 7.66 (0.92) | 10.04 (4.12) | 7.70 (0.84) | 10.42 (4.04) | 7.61 (0.84) | 8.13 (0.99) |

| Post-CPT | 7.85 (2.30) | 8.77 (1.50) | 9.12 (3.12) | 8.40 (1.39) | 9.14 (3.11) | 8.40 (1.39) | 8.53 (1.24) |

| Reactivity to CPT | −1.63 (0.83) | 1.11 (1.11) | −0.93 (1.11) | 0.70 (1.04) | −1.28 (1.20) | 0.78 (1.03) | 0.40 (0.88) |

Notes:

Depressed at 4 weeks postpartum > Not Depressed at 4 weeks postpartum, p < .05.

Mothers’ self-reported ALEs and HPA axis stress reactivity

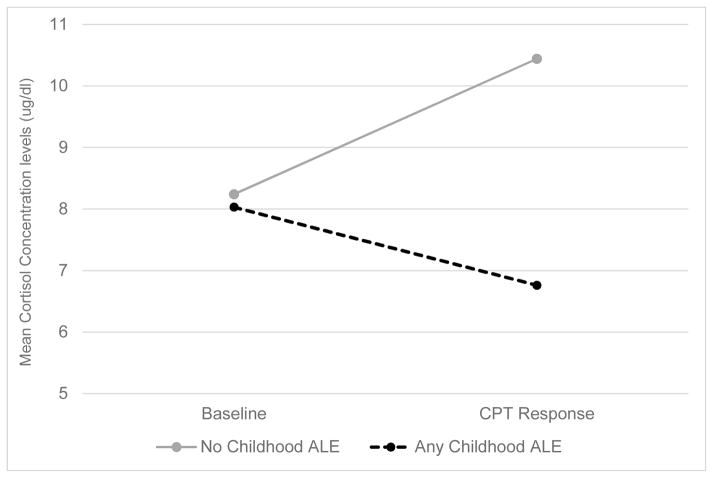

Table 3 shows that with the exception of women with a history of an infant-related ALE, ACTH levels decline from pre to post-CPT. Additional analysis revealed that any infant-related ALE was associated with greater ACTH reactivity (F (1, 25) = 5.29, p = 0.030). Subsequent analyses indicated that this difference resulted because women without infant-related ALEs exhibited a significant decrease in ACTH reactivity from pre- to post-CPT (t (22) = −2.39, p = 0.026) while women with infant-related ALEs showed a nonsignificant increase (t (3) = 0.99, p = 0.393). There was also a pattern of reduced post-CPT ACTH levels in all women who experienced any form of ALE, though only a history of any childhood ALE proved significant. Specifically, there was also a significant association between any childhood ALE and CORT reactivity to the CPT since those with any childhood ALE exhibited blunted CORT reactivity (F (1, 25) = 4.41, p = 0.045). Subsequent t-tests indicated that women with any childhood ALE exhibited a marginally significant decrease in CORT response to the CPT (t (13) = −1.96, p = 0.072) while there was no significant change in women with no history of childhood ALEs (t (12) = 1.41, p = 0.185) (see Figure 2).

Table 3.

Mean (+SEM) HPA axis measures at baseline and in response to CPT by ALE (n=27)

| Any childhood ALE | Any adulthood ALE | Any infant-related ALE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 13) | Yes (n = 14) | No (21) | Yes (6) | No (23) | Yes (4) | |

| LogACTH (pg/ml) | ||||||

| Pre-CPT | 4.39 (0.09) | 4.59 (0.17) | 4.51 (0.13) | 4.43 (0.10) | 4.44 (0.07) | 4.82 (0.59) |

| Post-CPT | 4.36 (008) | 4.56 (0.20) | 4.49 (0.14) | 4.36 (0.08) | 4.39 (0.07) | 4.92 (0.66) |

| Reactivity to CPT | −0.03 (0.04) | −0.03 (0.03) | −0.02 (0.03) | −0.07 (0.05) | −0.05 (0.02) | 0.09 (0.00)* |

| Cortisol (ug/dl) | ||||||

| Pre-CPT | 8.24 (1.00) | 8.03 (1.71) | 8.49 (1.14) | 6.88 (2.09) | 8.63 (1.12) | 5.28 (1.15) |

| Post-CPT | 10.44 (2.15) | 6.76 (1.23) | 9.04 (1.52) | 6.77 (1.70) | 9.14 (1.42) | 5.06 (0.86) |

| Reactivity to CPT | 2.02 (1.56) | −1.27 (0.65)* | 0.54 (1.02) | −0.11 (1.81) | 0.51 (1.03) | −0.22 (0.61) |

Notes:

p < .05

Figure 2.

Mean serum CORT Concentration Levels at Baseline and in Response to the CPT by History of Any Childhood ALE Measured at 8 weeks Postpartum (n= 27)

Perinatal Depression Status and HPA axis stress reactivity

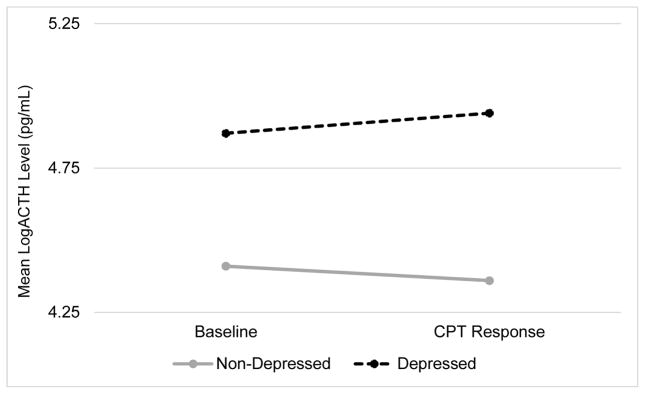

When comparing women with versus without PND at 4 weeks postpartum, those with PND had greater ACTH stress reactivity to the CPT than those without PND (F (1, 25) = 5.55, p = 0.027) at 8 weeks postpartum when stress reactivity was assessed. As Figure 3 illustrates, this is because women without PND exhibited a significant decrease in ACTH in response to the CPT (t (21) = −2.45, p = 0.023) while those with PND showed no response (t (4) = p = 1.11, p = 0.329). Though only marginally significant differences were found in ACTH reactivity by prenatal depression (F (1, 25) = 3.55, p = 0.071) and none were observed by PND at 8 weeks (F (1, 25) = 1.54, p = 0.226), a similar pattern was observed in those without PND in pregnancy and at 8 weeks postpartum who tended to exhibit blunted ACTH reactivity (t (19) = −2.29, p = 0.034 and t (21) = −1.80, p = 0.087, respectively), while those with PND showed no ACTH reactivity to the CPT (t (6) = 0.77, p = 0.472 and t (4) = 0.436, p = 0.685, respectively).

Figure 3.

Mean Log transformed plasma ACTH Concentration Levels at Baseline and in Response to the CPT by 4 week PND Measured at 8 weeks Postpartum (n= 27)

Regarding CORT, Table 2 shows a general pattern of blunted reactivity to the CPT in those with PND at any time point relative to those without PND. Women with PND showed a decrease in CORT from pre- to post CPT (t (20) = 1.00, t (21) = 0.67, t (21) = 0.76, ps > 0.330) while those without PND showed an increase from pre- to post-CPT (t (6) = −1.97, t (4) = −0.83, t (4) = −1.07, ps > 0.097), though these differences were not statistically significant.

Relationship of PND to pain sensitivity to the CPT

Pain tolerance was positively and significantly correlated with pain threshold in the full sample (r = 0.428, p < 0.026, not shown). As Table 4 shows, on average, pain threshold was reported at 17.22 (SD = 8.59) seconds and pain tolerance was reported at 39.44 (SD = 53.75) seconds after the onset of the CPT stressor. Women who had suffered depression at any study time point showed a pattern of lower mean pain threshold (F (1, 25) = 2.41, 0.97, 0.21, ps > 0.133) and tolerance times compared to non-depressed women, though these differences were not statistically significant (F (1, 25) =0.96, 0.46, 0.34, ps > 0.336).

Table 4.

Mean (SD) Pain outcomes measured at postpartum week 8 as a function of depression status over the course of the study (N = 27)

| Prenatal Depressed (n = 7) | Prenatal Nondepressed (n = 20) | 4 weeks Postpartum Depressed (n = 5) | 4 weeks Postpartum Nondepressed (n = 22) | 8 weeks Postpartum Depressed (n = 5) | 8 weeks Postpartum Nondepressed (n = 22) | All women at 8 weeks (n = 27) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPDS | 12.43 (3.21) | 3.70 (2.36) | 14.00 (1.58) | 3.09 (3.10) | 12.00 (1.87) | 2.77 (3.13) | 4.48 (4.67) |

| Pain Threshold | 13.00 (9.29) | 18.70 (8.05) | 13.80 (10.28) | 18.00 (8.23) | 15.60 (9.07) | 17.59 (8.65) | 17.22 (8.59) |

| Pain Tolerance | 22.29 (12.87) | 45.45 (61.28) | 24.60 (14.28) | 42.82 (58.94) | 26.60 (13.44) | 42.36 (59.11) | 39.44 (53.75) |

| Pain Intensity | 59.29 (25.24) | 65.00 (19.80) | 69.00 (23.02) | 62.27 (20.86) | 73.00 (24.90) | 61.36 (21.01) | 63.52 (20.98) |

| Pain Unpleasantness | 55.00 (24.32)a | 74.90 (23.19) | 55.00 (23.98) | 73.09 (24.09) | 63.00 (24.29) | 71.27 (25.03) | 69.74 (24.67) |

Notes:

prenatal depressed < prenatal nondepressed p = 0.065

Also shown in Table 4, on average, at the point of pain tolerance, women reported a mean pain intensity rating of 63.52 (SD = 20.98) and pain unpleasantness rating of 69.74 (SD = 24.67) based on a 0 to 100 visual analogue scales. While not statistically significant, results shown in Table 4 suggest a pattern of higher pain intensity ratings in response to the CPT (F (1, 25) = 0.38, 0.41, 1.27, ps > 0.271), but lower mean pain unpleasantness ratings F (1, 25) = 3.73, 2.30, 0.45, ps > 0.065) among depressed versus non-depressed women.

Pain sensitivity and relationship to HPA axis measures

Cortisol reactivity to the CPT stressor showed the most consistent relationships with pain sensitivity. In keeping with endogenous pain regulation by HPA axis reactivity, there was a positive and significant correlation between pain tolerance and CORT reactivity to the CPT (r = 0.453, p = 0.018) (see Table 5). Although the correlations between CORT reactivity and pain threshold, intensity, and unpleasantness are in directions consistent with analgesic effects, they did not reach statistical significance (r = 0.21, −0.15, −0.16, respectively; p > 0.294).

Table 5.

Pearson Correlations with Pain Measures and Stress Hormones measured at 8 weeks postpartum (N = 27)

| LogACTH Baseline | LogACTH +20 Response | LogACTH Reactivity | CORT Baseline | CORT +20 Response | CORT Reactivity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain Threshold (seconds) | 0.040 | −0.018 | −0.258 | −0.175 | 0.009 | 0.210 |

| Pain Tolerance (seconds) | 0.052 | 0.059 | 0.055 | −0.016 | 0.306 | 0.453* |

| Pain Intensity Rating (0–100) | 0.128 | 0.099 | −0.085 | 0.117 | −0.016 | −0.154 |

| Pain Unpleasantness Rating (0–100) | −0.010 | −0.055 | −0.217 | −0.062 | −0.159 | −0.156 |

Notes:

p < .05

Discussion

This is the first study to examine associations between ALEs, HPA axis stress reactivity, and PND in a sample of Latinas. As expected, we found that women with a history of any childhood ALE had generally higher depressive symptom scores at each of the pre- and postnatal time points but particularly so during the prenatal period. These findings support previous studies highlighting the vulnerability to PND in women with early life abuse histories (Alvarez-Segura et al., 2014; Buist & Janson, 2001; Faisal-Cury et al., 2013; Meltzer-Brody et al., 2013; Plaza et al., 2012; Rodríguez et al., 2010).

A history of childhood ALEs has also been shown to predict HPA axis dysregulation in adulthood (Heim et al., 2008), and while our results support these previous findings, they are novel in the focus on Latina women in the perinatal period. We observed that women with a history of ALEs, including infant-related adversity and childhood abuse, exhibited greater ACTH reactivity and blunted CORT reactivity, respectively, to the CPT in comparison to women without such a history. These findings are consistent with other studies in women with childhood abuse (Heim, Newport, Bonsall, Miller, & Nemeroff, 2001), but this has not been tested in women with infant-related adversity. While there is evidence of the deleterious effects infant-related ALEs can have on women’s mental health (Reynolds, 1997), less is known about the physiological consequences of such events on stress reactivity. This is among the first studies to explore these associations. Future studies should examine links between infant-related ALEs and neuroendocrine function in mothers.

The significant effects that we obtained demonstrating greater ACTH but blunted CORT stress reactivity in those with a history of ALEs mirror the pattern of results when HPA axis stress reactivity was examined as a function of PND status. Those with PND at four weeks postpartum had significantly greater ACTH reactivity to the CPT and, although not significant, there was a general pattern for blunted CORT stress reactivity in women with depression at any time point in the study. This HPA axis profile is worth comment. First, the greater ACTH reactivity, which represents the central drive by the pituitary on the adrenal cortex, in combination with blunted CORT reactivity, suggests possible impairment in negative feedback mechanisms regulating homeostasis of the HPA axis (Kumar et al., 2006). This HPA axis pattern was common to both those with perinatal depression and those with a history of ALEs suggesting a potential shared mechanism of risk that links a history of ALEs to PND. Second, it is noteworthy that in the analyses as a function of ALEs and in the analyses as a function of PND, where significant differences in ACTH reactivity emerged, they were driven by the non-affected groups who showed a significant decrease in ACTH in response to the CPT stressor. These findings support previous findings with non-Latina mothers (Jolley et al., 2007), where women without PND exhibited a decreased ACTH response to stress. It is interesting to speculate that the perinatal period provides a unique context for HPA axis reactivity given the adaptive state of high cortisol in pregnancy and the naturally-occurring reduction of that hormone and that reduced central drive on the adrenal cortex in response to stress may be adaptive during pregnancy and in the immediate postpartum period. This is an emerging area of inquiry that requires further investigation, particularly within the context of PND.

This study further documented in a sample of postpartum Latina women the expected relationship between greater CORT reactivity to the CPT stressor and increased pain tolerance, when analyzed in the sample as a whole, which is congruent with the expected HPA axis endogenous pain regulatory effect (Godfrey et al., 2014; Mechlin et al., 2005). To the extent that greater cortisol reactivity to the CPT would be expected to be associated with decreased sensitivity to painful stimuli, the pattern of blunted cortisol reactivity to the CPT seen in women with depression at all time points relative to their non-affected counterparts may have contributed to their general pattern of enhanced sensitivity to cold pressor pain (reflected in their nonsignificant pattern of lower pain threshold and tolerance times and higher pain intensity ratings). While speculative, the diminishment of endogenous pain regulation by blunted cortisol reactivity to stress may represent an additional form of HPA axis dysregulation in Latina women with perinatal depression that would have relevance not only to affect but to the experience of somatic symptomatology in the postpartum period. This interpretation is consistent with the evidence that dysregulation of the HPA axis is associated with altered sensory response to pain (Kuehl, Michaux, Richter, Schächinger, & Anton, 2010).

Further exploration of pain processing in PND is recommended given the observed pattern of lower pain threshold and tolerance and reported higher pain intensity to the CPT in women with PND compared to non-depressed women. The trends are congruent with previous studies showing that depressed populations report higher pain intensity (Mok & Lee, 2008). We also found that women with PND reported marginally significant lower pain unpleasantness ratings than nondepressed women, which was not expected. The dissociations between pain intensity and pain unpleasantness in those with depression is intriguing. One possible explanation for lower pain unpleasantness ratings in those with depression might result from the fact that the unpleasantness dimension of pain perception reflects the affective or emotional properties of pain, and depressed women might experience less emotional responsiveness than nondepressed women (Sloan, Strauss, Quirk, & Sajatovic, 1997), whereas pain intensity reflects the sensory, discriminatory properties of pain (W. B. Smith, Gracely, & Safer, 1998). An alternative explanation could be found in neurological activation of emotional processing regions in the brain. For example, depressed women might exhibit less activation in regions, such as the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (Berna et al., 2010), the amygdala, and the anterior cingulate cortex (Berna et al., 2010), which have been implicated in pain and emotion processing, and depression. Recent neuroimaging studies revealed dysregulation in related brain regions in mothers with PPD (Moses-Kolko et al., 2010). Further examination using neuroimaging strategies might help elucidate the dissociation found between pain intensity and pain unpleasantness in our depressed Latina mothers.

Conclusions

This study is the first to explore relationships among ALEs, PND and HPA axis responses to a cold pressor test in a birth cohort of Latinas. Our findings showed significant univariate relationships, even in this small sample, between: 1) ALEs and PND; 2) ALEs and HPA axis stress reactivity; and 3) PND and HPA stress reactivity, providing supportive evidence for testing a mediational model of PND development in Latinas (Lara-Cinisomo et al., 2016). Our secondary analyses involving pain sensitivity to the CPT in this sample, while not yielding statistically significant findings, are worth examining in a larger sample given the consistent pattern of results for heightened pain sensitivity during the postpartum period in Latinas with prenatal and postpartum depression. However, this study is not without limitations. First, our sample size was very small. As Table 2 shows, the depressed groups had large standard errors compared to the nondepressed groups. This speaks to our small sample size and high Type II error rates, which prevented us from detecting significant effects. Still, while its small sample size limits definitive conclusions, the study’s findings are meant to serve a heuristic value for future research in this vulnerable population. A second notable limitation was the limited number of neuroendocrine sampling points following the onset of the CPT, which hampered our ability to examine the full neuroendocrine response to the stressor. Third, our study lacked information regarding medication use, which might have affected neuroendocrine results.

Implications for Practice

This first-of-its-kind study shows interesting findings, including those suggesting that information taken during a clinical history, such as ALEs and depressive symptom levels, are predictive of HPA axis reactivity in Latina women during the postpartum period. Our finding that cortisol reactivity to stress served as an endogenous modulator of pain sensitivity in this sample suggests that the blunted cortisol reactivity to stress observed in those with a history of ALEs or with PND may have implications for modulation of clinical pain sensitivity in Latina women during the perinatal period. While this needs to be empirically tested, if confirmed, it could influence breastfeeding practices in those women with PND. As such, our findings demonstrate the potential for future research with this highly vulnerable population, which should include larger numbers of Latinas with or without a history of adverse events to better estimate the association between pain sensitivity, HPA axis function and PND to increase the duration of breastfeeding and improve maternal outcomes. A larger sample of Latinas will also provide investigators with the necessary statistical power to test the hypotheses generated here. The proposed lines of research will allow investigators to explore multi-variable models that integrate variables, such as the timing of ALEs, stress reactivity, breastfeeding practices, and PND to test various causal pathways. Future studies might explore the interaction between these factors, as well as the modifying effect of predictors (e.g., ALEs) on PND to better inform treatment approaches and clinical care.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funders

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (5T32MH093315-03; Drs. Girdler & Rubinow, PIs and MH085165-01A1; Dr. Meltzer-Brody), the Foundation of Hope for Research and Treatment of Mental Illness, and the North Carolina Translational and Clinical Sciences (NC TraCS) Institute for their support of this research.

The authors wish to thank the mothers and their infants who participated in this innovative study. This study could not have been possible without their impressive commitment to our work. The authors would also like to acknowledge the hard work of our impressive research assistants and technical staff: Kathryn McKenney, Sierra Pierce, Mala Elam, and Chihiro Christmas.

Biographies

Sandraluz Lara-Cinisomo, EdM, PhD was a T32 NIH Fellow in reproductive mood disorders at the UNC Chapel Hill when this work was completed. She has recently joined the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign faculty. Her research interests include perinatal mood disorders in Latina and military populations.

Karen Grewen, PhD is an Associate Professor of Psychiatry, Neurobiology and Psychology at UNC Chapel Hill. Dr. Grewen examines the effects of social affiliation and stress on endocrine, neural, and cardiovascular activity, with a focus on potential biologic mediators.

Susan Girdler, PhD is Professor in the Department of Psychiatry, Director for the UNC Chapel Hill Psychiatry Stress and Health Research Program and Co-Director of the first NIH-funded T32 in Reproductive Mood Disorders. Dr. Girdler’s research interests include the adrenergic and neuroendocrine basis of reproductive mood disorders.

Jayme Wood, BS MA is a master’s student in Bioarchaeology and Forensic Anthropology at the University College London and was a research assistant in the study while attending the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Samantha Meltzer-Brody, MD, MPH is a clinician and NIH-funded investigator at UNC Chapel Hill where she is an Associate Professor, Associate Chair of Faculty Development in the Department of Psychiatry, and Director of the UNC Perinatal Psychiatry Program of the UNC Center for Women’s Mood Disorders.

Footnotes

Author Disclosures Statement

Samantha Meltzer-Brody received a Research grant from Astra Zeneca. No other competing financial interests exist.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alvarez-Segura M, Garcia-Esteve L, Torres A, Plaza A, Imaz ML, Hermida-Barros L, … Burtchen N. Are women with a history of abuse more vulnerable to perinatal depressive symptoms? A systematic review. Archives of women’s mental health. 2014;17(5):343–357. doi: 10.1007/s00737-014-0440-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Arvat E, Di Vito L, Lanfranco F, Maccario M, Baffoni C, Rossetto R, … Ghigo E. Stimulatory effect of adrenocorticotropin on cortisol, aldosterone, and dehydroepiandrosterone secretion in normal humans: Dose-response study. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2000;85(9):3141–3146. doi: 10.1210/jc.85.9.3141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bair M, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K. Depression and Pain Comorbidity: A Literature Review. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2003;163:2433–2445. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender R, Lange S. Adjusting for multiple testing—when and how? Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2001;54(4):343–349. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00314-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berna C, Leknes S, Holmes EA, Edwards RR, Goodwin GM, Tracey I. Induction of Depressed Mood Disrupts Emotion Regulation Neurocircuitry and Enhances Pain Unpleasantness. Biological psychiatry. 2010;67(11):1083–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch M, Daly RC, Rubinow DR. Endocrine factors in the etiology of postpartum depression. COMPREHENSIVE PSYCHIATRY. 2003;44(3):234–246. doi: 10.1053/comp.2003.50014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blume J, Douglas SD, Evans DL. Immune suppression and immune activation in depression. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2011;25(2):221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand SR, Brennan PA, Newport DJ, Smith AK, Weiss T, Stowe ZN. The impact of maternal childhood abuse on maternal and infant HPA axis function in the postpartum period. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35(5):686–693. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buist A, Janson H. Childhood sexual abuse, parenting and postpartum depression—a 3-year follow-up study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25(7):909–921. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(01)00246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke HM, Davis MC, Otte C, Mohr DC. Depression and cortisol responses to psychological stress: A meta-analysis. PSYCHONEUROENDOCRINOLOGY. 2005;30(9):846–856. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneune.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos M, Wallace G, Goodwin G. Postpartum Depression among African-American and Latina Mothers Living in Small Cities, Towns, and Rural Communities. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2016:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s40615-016-0295-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Census, U. S. Hispanics by the Numbers. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.infoplease.com/spot/hhmcensus1.html.

- Choi JC, Chung MI, Lee YD. Modulation of pain sensation by stress-related testosterone and cortisol. Anaesthesia. 2012;67(10):1146–1151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2012.07267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corruble E, Guelfi J-D. Pain complaints in depressed inpatients. Psychopathology. 2000;33(6):307–309. doi: 10.1159/000029163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox EQ, Stuebe A, Pearson B, Grewen K, Rubinow D, Meltzer-Brody S. Oxytocin and HPA stress axis reactivity in postpartum women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;55:164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JL, Chapman G, Murray D, Jones P. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in non-postnatal women. Journal of affective disorders. 1996;39(3):185–189. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(96)00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science. 1987;150(6):782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rezende MG, Garcia-Leal C, de Figueiredo FP, Cavalli RdC, Spanghero MS, Barbieri MA, … Del-Ben CM. Altered functioning of the HPA axis in depressed postpartum women. Journal of affective disorders. 2016;193:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faisal-Cury A, Menezes PR, d’Oliveira AFPL, Schraiber LB, Lopes CS. Temporal relationship between intimate partner violence and postpartum depression in a sample of low income women. Maternal and child health journal. 2013;17(7):1297–1303. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1127-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. User’s guide for the Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders SCID-I: clinician version. American Psychiatric Pub; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Esteve L, Giménez A, Gurrutxaga ML, García P, Terrén C, Gelabert E. Maternity, Migration, and Mental Health: Comparison Between Spanish and Latina Immigrant Mothers in Postpartum Depression and Health Behaviors. In: Lara-Cinisomo S, Wisner KL, editors. Perinatal Depression among Spanish-Speaking and Latin American Women. Springer; New York: 2014. pp. 15–37. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Esteve Ls, Ascaso C, Ojuel J, Navarro P. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in Spanish mothers. Journal of affective disorders. 2003;75(1):71–76. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;106(5 Pt 1):1071–1083. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaynes BN, Gavin N, Meltzer-Brody S, Lohr KN, Swinson T, Gartlehner G, … Miller WC. Perinatal depression: prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomes. Evidence report/technology assessment (Summary) 2005;(119):1–8. doi: 10.1037/e439372005-001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geva N, Pruessner J, Defrin R. Acute psychosocial stress reduces pain modulation capabilities in healthy men. PAIN. 2014;155(11):2418–2425. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girdler SS, Maixner W, Naftel HA, Stewart PW, Moretz RL, Light KC. Cigarette smoking, stress-induced analgesia and pain perception in men and women. Pain. 2005;114(3):372–385. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn LM, Davis EP, Sandman CA. New insights into the role of perinatal HPA-axis dysregulation in postpartum depression. Neuropeptides. 2013;47(6):363–370. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey KM, Strachan E, Dansie E, Crofford LJ, Buchwald D, Goldberg J, … Afari N. Salivary Cortisol and Cold Pain Sensitivity in Female Twins. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2014;47(2):180–188. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9532-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon JL, Johnson J, Nau S, Mechlin B, Girdler SS. The Role of Chronic Psychosocial Stress in Explaining Racial Differences in Stress Reactivity and Pain Sensitivity. Psychosomatic medicine. 2017;79(2):201–212. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groer MW, Morgan K. Immune, health and endocrine characteristics of depressed postpartum mothers. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32(2):133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannibal KE, Bishop MD. Chronic Stress, Cortisol Dysfunction, and Pain: A Psychoneuroendocrine Rationale for Stress Management in Pain Rehabilitation. PHYSICAL THERAPY. 2014;94(12):1816–1825. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20130597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton DC, Harrison-Hohner J, Coste S, Dorato V, Curet LB, McCarron DA. Symptoms of Postpartum Depression and Breastfeeding. Journal of Human Lactation. 2005;21(4):444–449. doi: 10.1177/0890334405280947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Newport DJ, Bonsall R, Miller AH, Nemeroff CB. Altered pituitary-adrenal axis responses to provocative challenge tests in adult survivors of childhood abuse. The American journal of psychiatry. 2001;158(4):575–581. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Newport DJ, Mletzko T, Miller AH, Nemeroff CB. The link between childhood trauma and depression: Insights from HPA axis studies in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33(6):693–710. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell EA, Balbierz A, Wang J, Parides M, Zlotnick C, Leventhal H. Reducing postpartum depressive symptoms among black and Latina mothers: a randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2012;119(5):942. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318250ba48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM_Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23 (Version 23) Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Indraccolo U, Bracalente M, Di Iorio R, Indraccolo SR. Pain and breastfeeding: a prospective observational study. Clinical and experimental obstetrics & gynecology. 2012;39(4):454–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolley SN, Elmore S, Barnard KE, Carr DB. Dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in postpartum depression. Biological Research for Nursing. 2007;8(3):210–222. doi: 10.1177/1099800406294598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer EC, Caldwell CH, Welmerink DB, Welch KB, Sinco BR, Guzmán JR. Effect of the healthy MOMs lifestyle intervention on reducing depressive symptoms among pregnant Latinas. American journal of community psychology. 2013;51(1–2):76–89. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9523-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaassens ER, van Noorden MS, Giltay EJ, van Pelt J, van Veen T, Zitman FG. Effects of childhood trauma on HPA-axis reactivity in women free of lifetime psychopathology. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry. 2009;33(5):889–894. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig J, Jarczok MN, Ellis RJ, Bach C, Thayer JF, Hillecke TK. Two-Week Test–Retest Stability of the Cold Pressor Task Procedure at two different Temperatures as a Measure of Pain Threshold and Tolerance. Pain Practice. 2014;14(3):E126–E135. doi: 10.1111/papr.12142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozinszky Z, Dudas RB. Validation studies of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for the antenatal period. Journal of affective disorders. 2015;176:95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehl LK, Michaux GP, Richter S, Schächinger H, Anton F. Increased basal mechanical pain sensitivity but decreased perceptual wind-up in a human model of relative hypocortisolism. Pain. 2010;149(3):539–546. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M, Waldrop-Valverde D, Kumar AM, Fernandez JB, Gonzalez L, Ownby RL. Neuroendocrine Abnormalities in Drug Abusers and HIV-Infected Individuals: Cortisol Response to Cold Pressor Challenge. American Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2006;2(3):126–140. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo WH, Wilson TE, Holman S, Fuentes-Afflick E, O’Sullivan MJ, Minkoff H. Depressive symptoms in the immediate postpartum period among Hispanic women in three U.S. cities. Journal of immigrant health. 2004;6(4):145–153. doi: 10.1023/B:JOIH.0000045252.10412.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Cinisomo S, Girdler SS, Grewen K, Meltzer-Brody S. A Biopsychosocial Conceptual Framework of Postpartum Depression Risk in Immigrant and US-born Latina Mothers in the United States. Women’s Health Issues. 2016;26(3):336–343. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Cinisomo S, McKenney KM, Di Florio A, Meltzer-Brody S. Associations between postpartum depression, breastfeeding and oxytocin levels in Latina mothers. Breastfeeding Medicine. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2016.0213. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Cinisomo S, Plott J, Grewen K, Meltzer-Brody S. The Feasibility of Recruiting and Retaining Perinatal Latinas in a Biomedical Study Exploring Neuroendocrine Function and Postpartum Depression. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2016:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10903-016-0391-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Cinisomo S, Wisner KL, Meltzer-Brody S. Advances in Science and Biomedical Research on Postpartum Depression do not Include Meaningful Numbers of Latinas. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2015;17(6):1593–1596. doi: 10.1007/s10903-015-0205-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leserman J, Li Z, Drossman DA, Toomey TC, Nachman G, Glogau L. Impact of sexual and physical abuse dimensions on health status: development of an abuse severity measure. Psychosomatic medicine. 1997;59(2):152–160. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199703000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leserman J, Pence BW, Whetten K, Mugavero MJ, Thielman NM, Swartz MS, Stangl D. Relation of lifetime trauma and depressive symptoms to mortality in HIV. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164(11):1707–1713. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light KC, Girdler SS, Sherwood A, Bragdon EE, Brownley KA, West SG, Hinderliter AL. High stress responsivity predicts later blood pressure only in combination with positive family history and high life stress. Hypertension. 1999;33(6):1458–1464. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.6.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston G, Cohn DV. U.S. Birth Rate Falls to a Record Low; Decline Is Greatest among Immigrants. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lucero NB, Beckstrand RL, Callister LC, Sanchez Birkhead AC. Prevalence of postpartum depression among Hispanic immigrant women. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2012;24(12):726–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2012.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magiakou MA, Mastorakos G, Rabin D, Dubbert B, Gold PW, Chrousos GP. Hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone suppression during the postpartum period: Implications for the increase in psychiatric manifestations at this time. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 1996;81(5):1912–1917. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.5.8626857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Stress, adaptation, and disease - Allostasis and allostatic load. 1998;840:33–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinley JJ, Friedman BH. Autonomic responses to lateralized cold pressor and facial cooling tasks. Psychophysiology. 2015;52(3):416–424. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechlin MB, Maixner W, Light KC, Fisher JM, Girdler SS. African Americans show alterations in endogenous pain regulatory mechanisms and reduced pain tolerance to experimental pain procedures. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67(6):948–956. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188466.14546.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer-Brody S, Bledsoe-Mansori SE, Johnson N, Killian C, Hamer RM, Jackson C, … Thorp J. A prospective study of perinatal depression and trauma history in pregnant minority adolescents. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2013;208(3):211, e211. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mok LC, Lee IFK. Anxiety, depression and pain intensity in patients with low back pain who are admitted to acute care hospitals. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008;17(11):1471–1480. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses-Kolko EL, Perlman SB, Wisner KL, James J, Saul AT, Phillips ML. Abnormally Reduced Dorsomedial Prefrontal Cortical Activity and Effective Connectivity With Amygdala in Response to Negative Emotional Faces in Postpartum Depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167(11):1373–1380. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09081235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Trepka MJ, Pierre-Victor D, Bahelah R, Avent T. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Antenatal Depression in the United States: A Systematic Review. Maternal and child health journal. 2016;20(9):1780–1797. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-1989-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paananen M, O’Sullivan P, Straker L, Beales D, Coenen P, Karppinen J, … Smith A. A low cortisol response to stress is associated with musculoskeletal pain combined with increased pain sensitivity in young adults: a longitudinal cohort study. ARTHRITIS RESEARCH & THERAPY. 2015;17(1):355. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0875-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry B, Sorenson D, Meliska C, Basavaraj N, Zirpoli G, Gamst A, Hauger R. Hormonal basis of mood and postpartum disorders. Current women’s health reports. 2003;3(3):230–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passel JS, Livingston G, D’Vera C. Explaining Why Minority Births Now Outnumber White Births. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2012/05/17/explaining-why-minority-births-now-outnumber-white-births/

- Pedersen C, Leserman J, Garcia N, Stansbury M, Meltzer-Brody S, Johnson J. Late pregnancy thyroid-binding globulin predicts perinatal depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;65:84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaza A, Garcia-Esteve L, Torres A, Ascaso C, Gelabert E, Luisa Imaz M, … Martín-Santos R. Childhood physical abuse as a common risk factor for depression and thyroid dysfunction in the earlier postpartum. Psychiatry research. 2012;200(2–3):329–335. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds JL. Post-traumatic stress disorder after childbirth: the phenomenon of traumatic birth. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1997;156(6):831–835. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez MA, Valentine J, Ahmed SR, Eisenman DP, Sumner LA, Heilemann MV, Liu H. Intimate Partner Violence and Maternal Depression During the Perinatal Period: A Longitudinal Investigation of Latinas. Violence Against Women. 2010;16(5):543–559. doi: 10.1177/1077801210366959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santa Ana EJ, Saladin ME, Back SE, Waldrop AE, Spratt EG, McRae AL, … Brady KT. PTSD and the HPA axis: differences in response to the cold pressor task among individuals with child vs. adult trauma. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31(4):501–509. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwabe L, Haddad L, Schachinger H. HPA axis activation by a socially evaluated cold-pressor test. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33(6):890–895. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea A, Walsh C, MacMillan H, Steiner M. Child maltreatment and HPA axis dysregulation: relationship to major depressive disorder and post traumatic stress disorder in females. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30(2):162–178. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, VonKorff M, Piccinelli M, Fullerton C, Ormel J. An international study of the relation between somatic symptoms and depression. N Engl J Med. 1999;1999(341):1329–1335. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910283411801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan DM, Strauss ME, Quirk SW, Sajatovic M. Subjective and expressive emotional responses in depression. Journal of affective disorders. 1997;46(2):135–141. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(97)00097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Vale WW. The role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in neuroendocrine responses to stress. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2006;8(4):383–395. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2006.8.4/ssmith. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith WB, Gracely RH, Safer MA. The meaning of pain: cancer patients’ rating and recall of pain intensity and affect. Pain. 1998;78(2):123–129. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00122-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuebe AM, Grewen K, Meltzer-Brody S. Association Between Maternal Mood and Oxytocin Response to Breastfeeding. Journal of Women’s Health (2002) 2013;22(4):352–361. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhaus S, Held S, Schoofs D, Bültmann J, Dück I, Wolf OT, Hasenbring MI. Associations between fear-avoidance and endurance responses to pain and salivary cortisol in the context of experimental pain induction. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;52:195–199. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsigos C, Chrousos GP. Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, neuroendocrine factors and stress. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53(4):865–871. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00429-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim IS, Tanner Stapleton LR, Guardino CM, Hahn-Holbrook J, Dunkel Schetter C. Biological and psychosocial predictors of postpartum depression: systematic review and call for integration. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2015;11:99–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-101414-020426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayas LH, Jankowski KRB, McKee DM. Prenatal and Postpartum Depression among Low-Income Dominican and Puerto Rican Women. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2003;25(3):370–385. doi: 10.1177/0739986303256914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]