Abstract

Suicidal behavior imposes a tremendous cost, with current US estimates reporting approximately 1.3 million suicide attempts and more than 40,000 suicide deaths each year. Several recent research efforts have identified an association between suicidal behavior and the expression level of the spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase 1 (SAT1) gene. To date, several SAT1 genetic variants have been inconsistently associated with altered gene expression and/or directly with suicidal behavior. To clarify the role SAT1 genetic variation plays in suicidal behavior risk, we present a whole-gene sequencing effort of SAT1 in 476 bipolar disorder subjects with a history of suicide attempt and 473 subjects with bipolar disorder but no suicide attempts. Agilent SureSelect target enrichment was used to sequence all exons, introns, promoter regions, and putative regulatory regions identified from the ENCODE project within 10 kb of SAT1. Individual variant, haplotype, and collapsing variant tests were performed. Our results identified no variant or assessed region of SAT1 that showed a significant association with attempted suicide, nor did any assessment show evidence for replication of previously reported associations. Overall, no evidence for SAT1 sequence variation contributing to the risk for attempted suicide could be identified. It is possible that past associations of SAT1 expression with suicidal behavior arise from variation not captured in this study, or that causal variants in the region are too rare to be detected within our sample. Larger sample sizes and broader sequencing efforts will likely be required to identify the source of SAT1 expression level associations with suicidal behavior.

Keywords: Suicidal Behavior, Bipolar Disorder, Next-generation sequencing, Spermine / Spermidine N1-Acetyltransferase 1

Introduction

Suicidal behavior, which encompasses both suicide attempts and completed suicides, is responsible for approximately 650,000 emergency room visits each year within the United States [Chang et al., 2011] and is a leading cause of death worldwide, claiming in excess of 800,000 lives each year as reported by the World Health Organization [WHO, 2014]. Accumulating evidence exists of a genetic component contributing to the risk of suicidal behavior, which has an estimated heritability of 30-50% [Mann et al., 2009].

Several genetic studies have been undertaken to explain this heritability, and numerous potential risk loci have been identified. However, few findings have been consistently replicated. Among the most well-established findings is the spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase (SAT1) gene, which has been observed to have altered expression within the brains of suicide completers as compared to controls within several cohorts [Sequeira et al., 2006; Guipponi et al., 2009; Klempan et al., 2009; Le-Niculescu et al., 2013; Niculescu et al., 2015a; Niculescu et al., 2015b; Pantazatos et al., 2015]. Common genetic variation has been explored within the SAT1 gene and has been associated with suicidal behavior [Sequeira et al., 2006; Fiori and Turecki, 2010] and altered expression of the gene [Fiori et al., 2009], although these findings have been inconsistent [Guipponi et al., 2009]. The numerous sources of evidence in support of a role for SAT1 in suicidal behavior risk places this gene in a unique position among suicide candidate genes, warranting further detailed examination to understand the basis of these existing associations. SAT1 locus studies performed thus far have generally focused on only a handful of common genetic variants and/or have been performed within very small cohorts, leaving the contribution of SAT1 genetic variation to suicidal behavior risk unclear.

Functionally, SAT1 serves as a key enzyme within the polyamine processing pathway, which includes the regulation of polyamine compounds such as spermidine, spermine, and putrescine. Polyamines play many essential roles within gene regulation, cellular maintenance, cell function, cell fate determination, and oxidative stress response [Pegg, 2009]. Initial interest in SAT1 within psychiatric disease arose due to observations that polyamine levels demonstrate transient shifts within the brain in response to stressful stimuli [Gilad et al., 1995].

One potential relationship to suicidal behavior lies in the observation that intracellular polyamine concentrations significantly alter the function of neuronal ion channels, including excitatory glutamatergic receptors [Pegg, 2009]. In addition, recent evidence has demonstrated that treatment with lithium significantly alters SAT1 gene transcription levels in subjects at risk for suicidal behavior as well as normal controls, but not in subjects who died from suicide [Squassina et al., 2013]. Therefore, SAT1 has some biological plausibility in suicidal behavior risk.

In this study, we present the first complete gene sequencing effort of the SAT1 gene locus in a sample of individuals with bipolar disorder (BP). This population contains 476 BP individuals with a past history of suicide attempt (“attempters”) and 473 BP individuals with no past suicide attempts (“non-attempters”). We employed next generation targeted sequencing to capture all coding and many regulatory regions of the SAT1 locus. This design was implemented to provide a detailed examination of genetic variation within or near SAT1, including rare and potentially functional variants that likely would not have been captured as part of the majority of the existing study designs. As a result, this study provides the largest and most comprehensive examination of genetic variation of SAT1 in attempted suicide performed to date.

Materials and Methods

Study Subjects

This study is composed of 949 unrelated individuals of European-American descent who had been previously diagnosed with BP. This sample was taken from the same population utilized and described in our past genome wide association study (GWAS) [Willour et al., 2012]. Briefly, these subjects were ascertained as part of the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH) Genetics Initiative Bipolar Disorder Collaborative study as described elsewhere [Nurnberger et al., 1994; Potash et al., 2007; Zandi et al., 2007]. All included subjects were diagnosed following RDC, DSM-III-R, or DSM-IV criteria with 948 subjects meeting criteria for bipolar disorder, type 1 (BP1) and one subject meeting criteria for schizoaffective disorder, bipolar-type (SA-BP). All subjects were interviewed using the Diagnostic interview for Genetic Studies (DIGS) versions 1-4 [Nurnberger et al., 1994], which include questions about past suicide attempts and intent to die. Attempters were defined as any individual with at least one self-reported suicide attempt with moderate to serious intent to die (476 subjects). Non-attempters were defined as any individual with no self-reported past suicide attempt (473 subjects). Within these groups, there were 252 female and 224 male attempters and 251 female and 222 male non-attempters. Individuals were only included for analysis after being provided a description of the study followed by completion of an institutional review board-approved written informed consent document.

Sequencing

A custom SureSelect target enrichment (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara CA) assay was designed via the SureDesign Custom Design tool using custom scripts to select the gene region from University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) Table Browser data tracks [Karolchik et al., 2004] for Ensembl, UCSC, GENCODE genes v17, and RefSeq gene tracks. The assay was designed to capture the entire SAT1 locus of all alternative transcripts as represented in any of the datasets plus 2 kb upstream of all transcriptional start sites to capture transcriptional promoter elements. In addition, any region with overlapping signals for DNase hypersensitivity and ChIP-Seq identified transcription factor binding sites from the ENCODE project version 2 [ENCODE Project Consortium et al., 2012] within 10 kb up- or downstream of the largest merged SAT1 transcript was targeted for sequencing.

Sample preparation for sequencing was performed according to established Agilent protocols and utilizing a Sciclone Caliper robotic system (PerkinElmer, Waltham MA) at the University of Iowa Genomics Division. Briefly, shearing of 3 μg of high quality genomic DNA was performed in a Covaris E220 ultrasonicator (Covaris, Woburn MA) with quality assessment of the sheared fragments in an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100. DNA fragments were end-repaired, polyadenylated, and ligated to identifying adapters in order to generate sequencing libraries prior to hybridization. Multiplex sequencing of 16 samples per lane was performed using a HiSeq 2000 (Illumina, San Diego CA) following standard Illumina protocols.

Data preparation

A customized pipeline was generated to process samples and quality control the data. Briefly, samples were aligned to the human reference genome version hg19/GRCh37 using the Burrows-Wheeler aligner (BWA) version 0.6.2 [Li and Durbin, 2009]. Further processing was accomplished via SAMtools version 0.1.18 [Li et al., 2009], BAMtools version 2.2.3 [Barnett et al., 2011], and Picard version 1.88 (http://picard.sourceforge.net). Base score recalibration and realignment of sequence around suspected insertion/deletion (indel) sites was performed by the Genome Alignment Tool Kit (GATK) version 3.1.1 [McKenna et al., 2010]. Finally, genotypes of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and indels were generated via the haplotypecaller gVCF method of the GATK in all 949 samples simultaneously.

Genotyping was followed by rounds of variant recalibration in the GATK using recommended best practices. Variant calls with depth ≤ 10, genotyping quality score ≤ 20, heterozygote X-chromosome calls in males, and Y-chromosome calls in females were removed from the dataset. Variants were removed from the dataset if they violated Hardy Weinberg equilibrium (p< 1 × 10-6) via PLINK version 1.07 [Purcell et al., 2007], if they had missing calls for > 10% of the subjects, or if they failed the variant recalibration assessment.

Individual subject samples were subjected to rigorous quality control as part of the original GWAS study from which all of the samples were derived [Willour et al., 2012]. Subject data for the present study were assessed by comparing genotypes against existing GWAS genotypes. Three subjects were removed due to poor matchup with their GWAS genotypes, leaving the remaining samples with a GWAS call match rate of 99.8%. Subjects were also checked for expected sex using the plink version 1.07 “--check-sex” algorithm with no deviations identified.

All variants identified in the SAT1 gene were annotated for position and function using Annovar (version March 22, 2015) [Wang et al., 2010] and RegulomeDB (version 1.1) [Boyle et al., 2012]. Rare variants predicted to have functional effects were classified for analyses separately within translated (“coding”) and untranslated/non-coding regions (“regulatory”) of the SAT1 gene. Variants in coding and regulatory regions were placed in categories to define the level of evidence for the variant having a functional effect. “Coding disruptive” and “coding broad” classifications were applied to the coding functional variants following the example of recent exome analyses in schizophrenia [Fromer et al., 2014; Purcell et al., 2014]. Coding disruptive variants are composed of all stopgain, essential splice site, and frameshift variants. Coding broad variants include all disruptive variants plus any variant predicted to be damaging by any of six different bioinformatic packages included in ANNOVAR [Wang et al., 2010] annotation: SIFT [Ng and Henikoff, 2003], Polyphen2 HDIV and HVAR [Adzhubei et al., 2010], LRT [Chun and Fay, 2009], MutationTaster [Schwarz et al., 2010], and VEST version 3 [Carter et al., 2013].

Regulatory variants were similarly classified into two functional categories using RegulomeDB annotations [Boyle et al., 2012]. As suggested in the literature, regulatory functional classifications were defined based on scores of ≤ 2 being “likely to affect binding” (defined as “regulatory narrow”). Scores of 3-6 represent variants that are “less likely to affect binding” and were grouped with all regulatory narrow variants to make a broad regulatory variant group (scores 1-6; “regulatory broad”) [Boyle et al., 2012].

Statistical analysis

We examined all detected variants within the SAT1 regions independently using Firth's penalized logistic regression via the R logistf version 1.21 package [Heinze and Puhr, 2010]. All tests were performed using the count of minor alleles as the basis of the association test and were corrected for the covariates of sex and the first three principal component analysis (PCA) components for each subject.

Additional tests were used to collectively assess rare variants with two minor allele frequency (MAF) thresholds: MAF ≤ 0.05 (MAF05) and MAF ≤ 0.01 (MAF01). These rare variants were also required to have a bioinformatically predicted functional effect, as described above. Identified rare functional variants were assessed as a single group across a given genetic region (“gene burden”). Gene burden tests were performed via collapsing rare functional variants by subject using the CMC collapsing method [Li and Leal, 2008], leading to each subject having rare functional variation present or absent for each assessed gene/region. The gene burden tests were assessed using the Firth's penalized logistic regression package version 1.21 for R [Heinze and Puhr, 2010], suitable for small sample sizes typical in comparisons of rare variants. All gene burden tests included the covariates of sex and the first three components from each subject as generated from a PCA based on GWAS data available for all subjects.

Secondary analyses were also performed to assess additional features of interest within the SAT1 gene locus and to assess subpopulations of the dataset. A focused gene burden test was performed on a 4.3 kb promoter/upstream LD-block identified using Haploview v4.2 [Barrett et al., 2005] via the “confidence interval” analysis method initially published by Gabriel et al. [Gabriel et al., 2002]. This 4.3 kb block closely corresponds to the region of SAT1 where the majority of the past suicidal behavior and SAT1 expression associations with genetic variation have been identified [Sequeira et al., 2006; Fiori et al., 2009; Fiori and Turecki, 2010].

A haplotype analysis of all variants in the same 4.3 kb block was also performed by Haploview with default settings, including a 10,000 permutation test within Haploview to provide corrected p-values of the haplotype analyses. Briefly, all haplotypes with a frequency of > 0.01 were considered, the data were specified to be on the X-chromosome, and specified as a case/control sample.

Finally, we performed male- and female-specific assessments within all the described analyses to identify any sex-specific results. All assessments were corrected for multiple testing using the conservative Bonferroni method. Using this approach, the single variant threshold is 7.5 × 10-4 (67 total variants identified) and the region-based threshold is 6.25 × 10-3 (8 total primary tests). For single variant tests, we also employed a second method of correction for multiple testing due to the strong LD structure of SAT1 by correcting for the number of LD blocks in the region. This resulted in a significance threshold of 0.017 (3 blocks).

Power Analysis

Study power was calculated via Quanto version 1.2.4. This analysis was performed using the parameters of matched case-control, an alpha of 7.5 × 10-4, estimated population risk of suicidal behavior of 4.6%, log-additive inheritance for allele frequencies of 0.01 to 0.25, and estimating sample power for a relative risk of 1 to 10.

Results

Single Variant Testing

An overview of all 67 detected unique variant sites within the SAT1 locus and their frequencies within our dataset are shown within Figure 1 along with all association results in Table S1. None of the identified signals survived correction for multiple testing.

Figure 1.

Single variant association tests identified one variant with a nominal p-value < 0.05 within the SAT1 locus. The top signal identified was rs191760162:G>A (odds ratio = 11, nominal p = 0.031). This variant is very rare (MAF = 0.0034 within our dataset), was only identified within suicide attempters, and is within the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of the SAT1 gene.

Sex-specific tests were also performed within individual variants because a number of the existing associations with SAT1 reported in the literature arise from male-only cohorts [Sequeira et al., 2006; Fiori et al., 2009; Fiori and Turecki, 2010]. A sex-specific assessment of all individual variants did not identify any variants associated at nominal significance (p<0.05). The strongest variant signal identified within the sex-specific assessment was rs191760162, the same variant identified as the top overall signal. rs191760162 was predominantly found in females with a history of suicide attempt (4 female attempters; odds ratio = 8.9, nominal p = 0.058), was seen in only a single male attempter, and not seen in non-attempters.

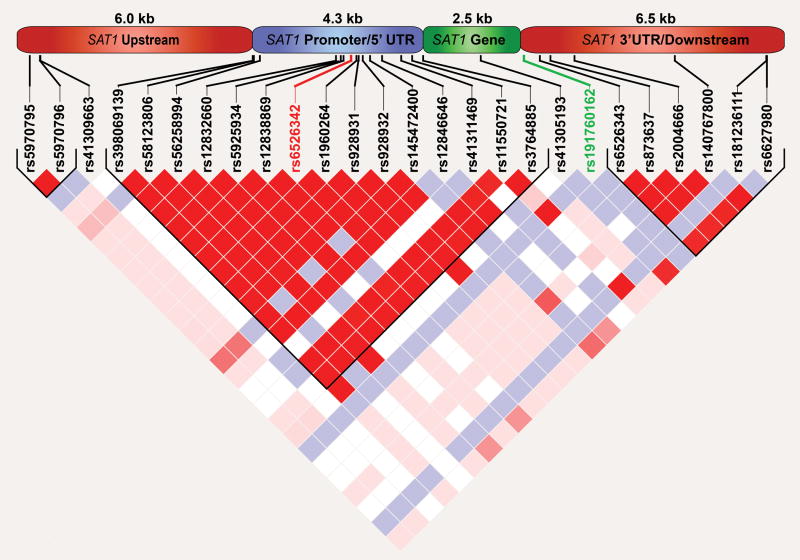

The placement of rs191760162 was assessed in relation to the linkage disequilibrium (LD) structure of the entire sequenced area via haploview v4.2 [Barrett et al., 2005] to ascertain any relationship it might have to previously identified variants associated with suicidal behavior in the SAT1 locus. This variant fell outside of an upstream LD block of approximately 4.3 kb that encompassed the previously associated rs6526342:C>A SNP and rs6151267 indel (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Previously Associated Variants

Variants within the SAT1 locus that were previously associated with suicidal behavior and/or SAT1 expression were also examined within our dataset for replication (Table 1). rs6526342 [Sequeira et al., 2006; Fiori et al., 2009] showed no evidence for association with attempted suicide within our dataset, neither in the all-subject analysis (OR = 0.99, p = 0.92) nor the sex-specific (male OR = 1.3, p = 0.29; female OR = 0.89, p = 0.44) analyses. For rs6526342, it is also important to note that our male-specific finding with OR > 1 implicates the “A” allele (minor allele) as the risk allele, which is opposite in direction to the previously reported findings that were assessed in an all-male sample.

Table 1. Covered Variants Previously Associated with Suicidal Behavior and/or SAT1 Expression.

| SNP ID (DBSNP 142) | Chr | Locus (hg19/GRCh37) | Attempter MAF | Non-Attempter MAF | Attempter Versus Non-Attempter Logistic Regression Results by Subject Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All OR | All pval | Male OR | Male pval | Female OR | Female pval | |||||

| rs6526342 [Sequeira et al., 2006, Fiori et al., 2009] | X | 23799738 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.99 | 0.92 | 1.3 | 0.29 | 0.89 | 0.44 |

| rs928931 [Fiori et al., 2009] | X | 23799933 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.97 | 0.82 | 1.3 | 0.34 | 0.89 | 0.44 |

Chr = chromosome; OR = Odds ratio; MAF = Minor allele frequency; pval = uncorrected p-value

The second variant that has been reported to be associated with suicidal behavior is the indel, rs6151267 [Fiori and Turecki, 2010]. This site did not pass the required quality thresholds we imposed on our dataset due to limitations in next-generation sequencing alignment techniques, which preclude confidently resolving highly repetitive or simple sequence regions such as those around rs6151267. However, two variants previously identified to be in strong LD with rs6151267 (rs928931:T>C and rs928932:G>A) were successfully captured with high quality reads. These two variants reside within 100 bp rs6151267 indel, and neither variant showed any evidence for association with attempted suicide in any population group assessed in our study (Table S1).

Region-based and Haplotype Assessments

Primary analyses of the coding and regulatory regions of SAT1 encompassing all rare (MAF ≤ 0.05 and MAF ≤ 0.01) variants predicted to have functional consequences yielded no results that could survive correction for multiple testing (Table 2). Likewise, no signals were detected within all sex-specific analyses or within promoter-only analyses focused on the 4.3 kb upstream LD block of the SAT1 locus where previous associations have been made with suicidal behavior (Table 2).

Table 2. Gene-Burden Results.

| Assessed Region | All Odds Ratio* | All Gene-Burden Pval | Male Odds Ratio* | Male Gene-Burden Pval | Female Odds Ratio* | Female Gene-Burden Pval | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAF 05 | MAF 01 | MAF 05 | MAF 01 | MAF 05 | MAF 01 | MAF 05 | MAF 01 | MAF 05 | MAF 01 | MAF 05 | MAF 01 | |

| SAT1 Whole Gene Coding Broad | 2.1 | 1.5 | 0.42 | 0.69 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 1.3 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.86 |

| SAT1 Whole Gene Coding Disruptive | 2.8 | 2.8 | 0.51 | 0.51 | - | - | - | - | 2.2 | 2.2 | 0.61 | 0.61 |

| SAT1 Whole Gene Reg Broad | 1.2 | 1.4 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 0.97 | 0.47 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 0.19 | 0.34 |

| SAT1 Whole Gene Reg Narrow | 1.1 | 0.96 | 0.84 | 0.95 | 1.9 | - | 0.43 | - | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.85 | 0.95 |

| SAT1 4.3 kb LD block Coding Broad | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.37 | 0.37 | - | - | - | - | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.32 | 0.32 |

| SAT1 4.3 kb LD block Coding Disruptive | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| SAT1 4.3 kb LD block Reg Broad | 1.3 | 1.4 | 0.27 | 0.56 | 0.90 | 0.17 | 0.80 | 0.19 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 0.17 | 0.19 |

| SAT1 4.3 kb LD block Reg Narrow | 2.2 | 2.2 | 0.62 | 0.62 | - | - | - | - | 2.7 | 2.7 | 0.53 | 0.53 |

Odds ratios are corrected for sample covariates. Any result denoted by a dash “-” represents a region that had no rare functional variation within the given population of our data sample, and thus could not be analyzed for that group. MAF= Minor allele frequency; Reg = regulatory; Pval = p-value corrected for covariates but uncorrected for multiple comparisons (uncorrected p-value < 0.0063 required for significance).

A haplotype analysis was also performed of this 4.3 kb upstream haplotype block using Haploview v4.2 [Barrett et al., 2005]. This analysis identified 5 common haplotypes (>1% frequency) for the 4.3 kb region within our dataset that accounted for the configurations in 98.4% of our subjects. None of the haplotypes showed any trend toward association within attempted suicide in any of the subject groups assessed (all attempters versus non-attempters and male-/female-specific assessments; Table S2).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study represents the largest and most comprehensive sequencing effort performed on the SAT1 gene locus to date. The study was designed to aid in answering the question of whether common and rare genetic variations within the SAT1 locus are significantly contributing to suicidal behavior risk. The lack of any significant signals after correction for multiple testing within a broad range of analyses performed, regardless of subject or variant set assessed, offers compelling evidence that genetic variation of moderate to high effect within the SAT1 gene is not a significant contributor to attempted suicide risk. There are a number of possible explanations for why we have not identified an association of variation within the SAT1 locus that bear consideration in light of these results.

Study Population and Size

Previous studies that have identified significant associations of SAT1 variants with suicidal behavior have been performed in notably different samples compared with the BP case-only attempter/non-attempter population examined in the current study. The closest match to our design was an examination of suicide attempters from varied psychiatric backgrounds compared with normal controls [Sokolowski et al., 2013], which found suggestive associations within the SAT1 locus after relaxing the false discovery rate threshold used for their primary analyses. The remaining genetic associations were identified within a French-Canadian cohort with a known founder effect and with a primary psychiatric background of major depressive disorder [Sequeira et al., 2006; Fiori and Turecki, 2010; Fiori et al., 2010]. These sample differences necessitate caution in drawing conclusions from direct comparisons of results.

Study size must also be considered carefully. Our study was well powered to detect associations of the magnitude (OR = 2.6-2.7) and within the MAF range (0.075-0.25) for the previously reported SAT1 variants [Sequeira et al., 2006; Fiori and Turecki, 2010]. We estimated 80% power to detect a signal of OR = 2.0 at an MAF of 0.070 within our dataset. Despite this power, it is possible that population differences between studies could lead to weaker signals within the associated regions. In addition, it is possible that very rare functional variants within the SAT1 locus may be present but would not be detectable without a much larger sample size.

Linkage Disequilibrium of the Region

Prior studies note a strong LD structure in the vicinity of the promoter and transcriptional start site of the SAT1 gene, where observed suicidal behavior association signals were concentrated [Fiori et al., 2009]. We also detected this LD region covering an area of approximately 4.3 kb that encompassed the first exon of SAT1 and the upstream promoter region of the gene (Figure 2). The capture of this region allowed a detailed examination of sites previously associated with suicidal behavior and provided a reference for the strongest signals detected within our own analyses.

Unfortunately, technological limitations in the alignment of repetitive or low complexity regions such as those inhabited by the previously associated indel, rs6151267, prevented us from confidently examining this variant directly. However, an association of rs6151267 with suicidal behavior within the 4.3 kb LD region would be reflected in the association signals of variants in high LD in the vicinity, as was observed by Sequeira et al [Fiori et al., 2009]. Several nearby variants were very well represented within our study within this LD block, but none showed any evidence of association with attempted suicide, reducing the likelihood that an association is present at rs6151267 within our data.

In addition, the top single variant signal detected in this study, rs191760162, was identified outside of the previously implicated 4.3 kb LD block, suggesting that this site is unlikely to have been tagged by, or be otherwise related, to the previously associated sites. The positioning of rs191760162 does make it a potential candidate for altering regulatory sites and gene expression, however. Specifically, rs191760162 sits within a predicted binding motif for the poorly described zinc finger transcription factor, ZNF35, within the 3′ UTR region of the SAT1 transcript as demonstrated by available ENCODE [ENCODE Project Consortium et al., 2012] evidence in the regulomeDB [Boyle et al., 2012] dataset. This variant is also predicted to be within an active transcriptional region via chromatin state assessment as part of the Roadmap Epigenetics Project [Bernstein et al., 2010]. However, cautious interpretation of rs191760162 and its potential functional consequences is warranted without replication in additional samples and assessment in combination with expression data for SAT1.

Other Explanations for Observed Expression Changes

The lack of significant variant associations with attempted suicide within the SAT1 locus suggests other potential causes for the previously associated changes in expression. Recent work by Lopez et al. has suggested that these changes may be associated with altered regulation by several miRNAs suspected to regulate SAT1 expression [Lopez et al., 2014]. In addition, epigenetic alterations within SAT1, dysregulation of any of the many regulatory genes or small molecular inducers of SAT1, alterations within distant trans-regulatory sites/enhancers for SAT1, and/or environmental factors could also explain differences in its expression behavior. Indeed, it was recently reported by Niola et al. that expression changes noted within the SAT1 gene secondary to application of lithium within cell lines were not found to be associated with genetic variation in the SAT1 locus within these cell lines, implicating other effectors of the altered expression [Niola et al., 2014].

Study Limitations

Our study had several limitations that must be considered in the interpretation of our findings. First, though the entire gene transcript locus was covered by our sequencing probes, only part of the complete upstream LD block investigated in previous studies was captured by our design due to a focus on capturing regions with multiple lines of evidence for functionality within the ENCODE dataset. There is the possibility that variants within regions not covered by our design are relevant to the regulation of SAT1 expression and to suicidal behavior.

In addition, the subjects we used differed in the suicidality phenotype from the majority of previous positive SAT1 association studies [Sequeira et al., 2006; Fiori et al., 2009; Fiori and Turecki, 2010]. Many of the previous variant associations were made via comparisons of suicide completers to psychiatric controls or normal controls as opposed to our attempter versus non-attempter design. We attempted to control for this discrepancy by sequencing only individuals with high suicidal intent. However, it remains to be clarified whether all underlying genetic risk factors of those that die from suicide are shared and detectable within those who attempt suicide.

Conclusion

This study has provided a detailed examination of the SAT1 gene locus, and found evidence to suggest that genetic variation of moderate to high effect size within the SAT1 locus may not significantly contribute to attempted suicide risk. This finding also suggests that expression changes observed in SAT1 that have been associated with suicidal behavior may arise from other sources, yet to be clarified. Therefore, this study aids in directing focus toward other potential regulatory sources of the SAT1 gene and broader sequencing efforts to elucidate the source of the many associations observed in SAT1 expression and suicidal behavior.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant R01MH079240 (Dr. Willour). Additional funds were provided by the University of Iowa Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP) training grant 5 T32 GM007337 (Eric Monson) and American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP) PDF-0-067-12 (Dr. Breen). We also wish to acknowledge the support of the University of Iowa Interdisciplinary Graduate Program in Genetics (Eric Monson, Sophia Gaynor, Dr. Willour, and Dr. Potash).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: All authors declare no conflicts of interest in the funding or direction of this research.

References

- Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7(4):248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett DW, Garrison EK, Quinlan AR, Stromberg MP, Marth GT. BamTools: a C++ API and toolkit for analyzing and managing BAM files. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(12):1691–1692. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(2):263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein BE, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Costello JF, Ren B, Milosavljevic A, Meissner A, Kellis M, Marra MA, Beaudet AL, Ecker JR, Farnham PJ, Hirst M, Lander ES, Mikkelsen TS, Thomson JA. The NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Mapping Consortium. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(10):1045–1048. doi: 10.1038/nbt1010-1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle AP, Hong EL, Hariharan M, Cheng Y, Schaub MA, Kasowski M, Karczewski KJ, Park J, Hitz BC, Weng S, Cherry JM, Snyder M. Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res. 2012;22(9):1790–1797. doi: 10.1101/gr.137323.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter H, Douville C, Stenson PD, Cooper DN, Karchin R. Identifying Mendelian disease genes with the variant effect scoring tool. BMC Genomics. 2013;14(Suppl 3):S3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-S3-S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang B, Gitlin D, Patel R. The depressed patient and suicidal patient in the emergency department: evidence-based management and treatment strategies. Emerg Med Pract. 2011;13(9):1–23. quiz 23-24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun S, Fay JC. Identification of deleterious mutations within three human genomes. Genome Res. 2009;19(9):1553–1561. doi: 10.1101/gr.092619.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium EP, Bernstein BE, Birney E, Dunham I, Green ED, Gunter C, Snyder M. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489(7414):57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiori LM, Mechawar N, Turecki G. Identification and characterization of spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase promoter variants in suicide completers. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(5):460–467. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiori LM, Turecki G. Association of the SAT1 in/del polymorphism with suicide completion. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;153B(3):825–829. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiori LM, Wanner B, Jomphe V, Croteau J, Vitaro F, Tremblay RE, Bureau A, Turecki G. Association of polyaminergic loci with anxiety, mood disorders, and attempted suicide. PLoS One. 2010;5(11):e15146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromer M, Pocklington AJ, Kavanagh DH, Williams HJ, Dwyer S, Gormley P, Georgieva L, Rees E, Palta P, Ruderfer DM, Carrera N, Humphreys I, Johnson JS, Roussos P, Barker DD, Banks E, Milanova V, Grant SG, Hannon E, Rose SA, Chambert K, Mahajan M, Scolnick EM, Moran JL, Kirov G, Palotie A, McCarroll SA, Holmans P, Sklar P, Owen MJ, Purcell SM, O'Donovan MC. De novo mutations in schizophrenia implicate synaptic networks. Nature. 2014;506(7487):179–184. doi: 10.1038/nature12929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel SB, Schaffner SF, Nguyen H, Moore JM, Roy J, Blumenstiel B, Higgins J, DeFelice M, Lochner A, Faggart M, Liu-Cordero SN, Rotimi C, Adeyemo A, Cooper R, Ward R, Lander ES, Daly MJ, Altshuler D. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science. 2002;296(5576):2225–2229. doi: 10.1126/science.1069424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilad GM, Gilad VH, Casanova MF, Casero RA., Jr Polyamines and their metabolizing enzymes in human frontal cortex and hippocampus: preliminary measurements in affective disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 1995;38(4):227–234. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)00256-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guipponi M, Deutsch S, Kohler K, Perroud N, Le Gal F, Vessaz M, Laforge T, Petit B, Jollant F, Guillaume S, Baud P, Courtet P, La Harpe R, Malafosse A. Genetic and epigenetic analysis of SSAT gene dysregulation in suicidal behavior. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009;150B(6):799–807. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinze G, Puhr R. Bias-reduced and separation-proof conditional logistic regression with small or sparse data sets. Stat Med. 2010;29(7-8):770–777. doi: 10.1002/sim.3794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karolchik D, Hinrichs AS, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Sugnet CW, Haussler D, Kent WJ. The UCSC Table Browser data retrieval tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Database issue):D493–496. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klempan TA, Rujescu D, Merette C, Himmelman C, Sequeira A, Canetti L, Fiori LM, Schneider B, Bureau A, Turecki G. Profiling brain expression of the spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase 1 (SAT1) gene in suicide. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009;150B(7):934–943. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le-Niculescu H, Levey DF, Ayalew M, Palmer L, Gavrin LM, Jain N, Winiger E, Bhosrekar S, Shankar G, Radel M, Bellanger E, Duckworth H, Olesek K, Vergo J, Schweitzer R, Yard M, Ballew A, Shekhar A, Sandusky GE, Schork NJ, Kurian SM, Salomon DR, Niculescu AB., 3rd Discovery and validation of blood biomarkers for suicidality. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(12):1249–1264. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Leal SM. Methods for detecting associations with rare variants for common diseases: application to analysis of sequence data. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83(3):311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(14):1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, Genome Project Data Processing S The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(16):2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez JP, Fiori LM, Gross JA, Labonte B, Yerko V, Mechawar N, Turecki G. Regulatory role of miRNAs in polyamine gene expression in the prefrontal cortex of depressed suicide completers. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17(1):23–32. doi: 10.1017/S1461145713000941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ, Arango VA, Avenevoli S, Brent DA, Champagne FA, Clayton P, Currier D, Dougherty DM, Haghighi F, Hodge SE, Kleinman J, Lehner T, McMahon F, Moscicki EK, Oquendo MA, Pandey GN, Pearson J, Stanley B, Terwilliger J, Wenzel A. Candidate endophenotypes for genetic studies of suicidal behavior. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(7):556–563. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, Garimella K, Altshuler D, Gabriel S, Daly M, DePristo MA. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20(9):1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng PC, Henikoff S. SIFT: Predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3812–3814. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niculescu AB, Levey D, Le-Niculescu H, Niculescu E, Kurian SM, Salomon D. Psychiatric blood biomarkers: avoiding jumping to premature negative or positive conclusions. Mol Psychiatry. 2015a;20(3):286–288. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niculescu AB, Levey DF, Phalen PL, Le-Niculescu H, Dainton HD, Jain N, Belanger E, James A, George S, Weber H, Graham DL, Schweitzer R, Ladd TB, Learman R, Niculescu EM, Vanipenta NP, Khan FN, Mullen J, Shankar G, Cook S, Humbert C, Ballew A, Yard M, Gelbart T, Shekhar A, Schork NJ, Kurian SM, Sandusky GE, Salomon DR. Understanding and predicting suicidality using a combined genomic and clinical risk assessment approach. Mol Psychiatry. 2015b doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niola P, Gross JA, Lopez JP, Chillotti C, Deiana V, Manchia M, Georgitsi M, Patrinos GP, Alda M, Turecki G, Del Zompo M, Squassina A. Lithium-induced differential expression of SAT1 in suicide completers and controls is not correlated with polymorphisms in the promoter region of the gene. Psychiatry Res. 2014;220(3):1167–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurnberger JI, Jr, Blehar MC, Kaufmann CA, York-Cooler C, Simpson SG, Harkavy-Friedman J, Severe JB, Malaspina D, Reich T. Diagnostic interview for genetic studies. Rationale, unique features, and training. NIMH Genetics Initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(11):849–859. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950110009002. discussion 863-844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantazatos SP, Andrews SJ, Dunning-Broadbent J, Pang J, Huang YY, Arango V, Nagy PL, John Mann J. Isoform-level brain expression profiling of the spermidine/spermine N1-Acetyltransferase1 (SAT1) gene in major depression and suicide. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;79:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegg AE. Mammalian polyamine metabolism and function. IUBMB Life. 2009;61(9):880–894. doi: 10.1002/iub.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potash JB, Toolan J, Steele J, Miller EB, Pearl J, Zandi PP, Schulze TG, Kassem L, Simpson SG, Lopez V, Consortium NGIBD. MacKinnon DF, McMahon FJ. The bipolar disorder phenome database: a resource for genetic studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(8):1229–1237. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06122045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, Sham PC. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(3):559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell SM, Moran JL, Fromer M, Ruderfer D, Solovieff N, Roussos P, O'Dushlaine C, Chambert K, Bergen SE, Kahler A, Duncan L, Stahl E, Genovese G, Fernandez E, Collins MO, Komiyama NH, Choudhary JS, Magnusson PK, Banks E, Shakir K, Garimella K, Fennell T, DePristo M, Grant SG, Haggarty SJ, Gabriel S, Scolnick EM, Lander ES, Hultman CM, Sullivan PF, McCarroll SA, Sklar P. A polygenic burden of rare disruptive mutations in schizophrenia. Nature. 2014;506(7487):185–190. doi: 10.1038/nature12975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz JM, Rodelsperger C, Schuelke M, Seelow D. MutationTaster evaluates disease-causing potential of sequence alterations. Nat Methods. 2010;7(8):575–576. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0810-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sequeira A, Gwadry FG, Ffrench-Mullen JM, Canetti L, Gingras Y, Casero RA, Jr, Rouleau G, Benkelfat C, Turecki G. Implication of SSAT by gene expression and genetic variation in suicide and major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(1):35–48. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolowski M, Ben-Efraim YJ, Wasserman J, Wasserman D. Glutamatergic GRIN2B and polyaminergic ODC1 genes in suicide attempts: associations and gene-environment interactions with childhood/adolescent physical assault. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(9):985–992. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squassina A, Manchia M, Chillotti C, Deiana V, Congiu D, Paribello F, Roncada P, Soggiu A, Piras C, Urbani A, Robertson GS, Keddy P, Turecki G, Rouleau GA, Alda M, Del Zompo M. Differential effect of lithium on spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase expression in suicidal behaviour. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16(10):2209–2218. doi: 10.1017/S1461145713000655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(16):e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Preventing suicide: A global imperative. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mental_health/suicide-prevention/world_report_2014/en/

- Willour VL, Seifuddin F, Mahon PB, Jancic D, Pirooznia M, Steele J, Schweizer B, Goes FS, Mondimore FM, Mackinnon DF, Bipolar Genome Study C, Perlis RH, Lee PH, Huang J, Kelsoe JR, Shilling PD, Rietschel M, Nothen M, Cichon S, Gurling H, Purcell S, Smoller JW, Craddock N, DePaulo JR, Jr, Schulze TG, McMahon FJ, Zandi PP, Potash JB. A genome-wide association study of attempted suicide. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(4):433–444. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandi PP, Avramopoulos D, Willour VL, Huo Y, Miao K, Mackinnon DF, McInnis MG, Potash JB, Depaulo JR. SNP fine mapping of chromosome 8q24 in bipolar disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144B(5):625–630. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.