Abstract

Severe thrombocytopenia (platelets <50 ×109/L) is associated with very poor outcome of patients with myelofibrosis (MF). Since patients with primary myelofibrosis (PMF) differ from patients with post-essential thrombocythemia (PET-MF) and post-polycythemia vera myelofibrosis (PPV-MF), we aimed to evaluate the significance of low platelets among these patients. We present clinical characteristics and outcome of patients with either PMF, PPV-MF, or PET-MF, and thrombocytopenia who presented to our institution between 1984 and 2015. Of 1269 patients (877 PMF, 212 PPV-MF, 180 PET-MF), 11% and 14% had platelets either <50 ×109/L or between 50-100 ×109/L, respectively. Patients with platelets <50 ×109/L were most anemic and transfusion dependent, had highest blast count and unfavorable karyotype. In general, their overall and leukemia free survival was the shortest with median time of 15 and 13 months, respectively; with incidence of acute leukemia almost twice as high as in the remaining patients (6.9 vs 3.6 cases per 100 person-years). Nevertheless, this observation remains mostly significant for patients with PMF, as those with PEV/PVT-MF have already significantly inferior prognosis with platelets <100 × 109/L.

Keywords: primary myelofibrosis, post-essential thrombocythemia myelofibrosis, post-polycythemia vera myelofibrosis, thrombocytopenia, outcome

Introduction

Myelofibrosis (MF) is a Philadelphia chromosome negative myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) that includes primary myelofibrosis (PMF), post-polycythemia vera myelofibrosis (PPV-MF) and post-essential thrombocythemia myelofibrosis (PET-MF), with an incidence of 1.46 per 100,000 cases annually (1). The clinical picture of MF is variable, but mostly includes signs of ineffective and extramedullary hematopoiesis, such as anemia, leucoerythroblastic picture, symptomatic organomegaly (spleen, liver) causing abdominal pain, early satiety, and debilitating constitutional symptoms (2). The exact etiology of MF is unknown (3), however defective stem cell niche has been postulated (4). Activation of JAK/STAT pathway via somatic point mutations in JAK2V617F and MPLW515L, as well as abnormalities in calreticulin gene, has been demonstrated to be associated with MF (5–7). Therapeutic options in MF mostly represent supportive care (e.g., steroids, immunomodulatory drugs, JAK inhibitors) (8–10), with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (11) being the only curative strategy. Thrombocytopenia (platelets <100 ×109/L) is sometimes seen in patients with MF, and its negative prognostic impact has been incorporated in the Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System Plus (DIPSS-Plus) (12, 13). Recently, several reports showed additional significant negative impact of severe thrombocytopenia (<50 ×109/L) on prognosis of these patients (14, 15). Little is known about the impact of severe thrombocytopenia on the outcome of patients with PMF vs PPV-MF vs PET-MF, which we have aimed to evaluate here.

Method

In a retrospective cohort analysis we evaluated the clinical characteristics, therapy and outcome in patients with MF (separately for PMF, PPV-MF and PET-MF) with thrombocytopenia, who presented to our institution between years of 1984-2015. PMF was diagnosed according to 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, and PPV/PET-MF was diagnosed according to The International Working Group for Myelofibrosis Research and Treatment (IWG-MRT) criteria (16, 17). All relevant clinical and outcome data were collected from the patient’s medical charts at the time of presentation. Bone marrow fibrosis grading was assessed according to European Consensus criteria (18). Cytogenetic results were interpreted according to the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature, and unfavorable cytogenetic included complex karyotype or single or two abnormalities including +8, −7/7q-,i(17q), −5/5q-, 12p-, inv(3) or 11q23 rearrangement (12). Molecular testing was performed by real time PCR-based sequencing, using a next generation sequencing platform in our CLIA certified molecular diagnostic laboratory, as previously reported (19). Clinicopathological parameters (categorical and continuous variables) were analyzed by the Fisher’s exact, Kruskal–Wallis or Mann–Whitney U tests, as appropriate. Survival analyses were carried out with the Kaplan–Meier method and compared with the log-rank test. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the time of referral to the date of last-follow-up or death, whichever came first, and leukemia free survival (LFS) was calculated from the time of referral to the date of progression to acute leukemia or death from any cause. Sub-analysis of OS censored for stem cell transplantation (SCT) was also performed. All statistical computations were performed using SPSS, version 24.0 (Chicago, IL). The study was conducted using retrospective chart review protocol approved by institutional review board.

Results

Among all 1281 patients who presented to MDACC between January 1st 1984 and December 31st 2015, 1269 (99%: 877 PMF, 212 PPV-MF and 180 PET-MF) had available laboratory data and represent our study cohort. Fifty three percent of patients (n=678 [432 PMF, 139 PPV-MF, 107 PET-MF]) presented within 3 months of their original MF diagnosis, therefore referred to in this report as newly diagnosed. Eleven percent of patients (n=145) had platelets below 50 ×109/L (therefore titled “plt 50” group), 14% (n=179) had platelets between 50-100 ×109/L (“plt 50-100”), and 75% (n=948) had platelets >100 ×109/L (“plt 100”) at the presentation, respectively. The baseline characteristics and demographics are shown in Table 1, and comparison between plt 50 and plt 50-100 groups stratified by diagnosis in Table 2. Patients with PET-MF were represented more frequently in the group with plt 100, however, this wasn’t statistically significant, and the overall distribution of patients with different diagnoses and platelet counts was similar (Supplemental Figure 1.)

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of patients stratified based on platelet count

| All, N= 1269 | plt 1-50, N=145 | plt 51-100, N=178 | plt 101+, N=948 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DX PMF PPV-MF PET-MF |

877 (69) 212 (17) 180 (14) |

118 (81) 17 (12) 10 (7) |

137 (78) 32 (18) 7 (4) |

622 (66) 163 (17) 163 (17) |

|

| Males, N (%) | 771 (61) | 91 (63) | 127 (71) | 553 (58) | 0.002 |

| Median age, years (range) | 65 (17-94) | 68 (27-88) | 89 (17-89) | 65 (20-94) | <0.001 |

| Age below 65 yrs, N (%) | 638 (50) | 58 (40) | 67 (38) | 513 (54) | <0.001 |

| Median hgb (g/dL) | 10 (4-19) | 9 (5-16) | 10 (5-17) | 11 (4-19) | <0.001 |

| Hgb < 10 (g/dL), N (%) | 548 (43) | 98 (68) | 92 (52) | 358 (38) | <0.001 |

| Median WBC (×109/L) | 9.7 (0-361) | 6.7 (0-228) | 7.2 (2-200) | 10.4 (1-361) | 0.4 |

| WBC > 25 (×109/L), N (%) | 122 (17) | 27 (19) | 30 (17) | 165 (17) | 0.92 |

| PRBC transfusions, N (%) | 324 (26) | 90 (62) | 67 (38) | 167 (18) | <0.001 |

| Fibrosis grade ≥2, N (%) | 1011 (80) | 111 (77) | 141 (79) | 759 (80) | 0.78 |

| Spleen > 5 cm [BCM], N (%) | 631 (50) | 73 (50) | 94 (53) | 464 (49) | 0.65 |

| Splenectomy, N (%) | 153 (12) | 20 (14) | 18 (10) | 115 (12) | 0.44 |

| Symptoms, N (%) | 919 (72) | 106 (73) | 137 (77) | 676 (71) | 0.203 |

| Abnormal karyotype, N (%) | 427 (34) | 67 (46) | 68 (39) | 292 (31) | <0.001 |

| Unfavorable karyotype, N (%) | 145 (11) | 39 (27) | 21 (12) | 85 (9) | <0.0001 |

| Complex karyotype, N (%) | 55 (4) | 16 (11) | 9 (5) | 30 (3) | <0.001 |

| Mol. Mut. JAK2+ | 702 (55) | 66 (46) | 97 (54) | 539 (57) | 0.65 |

| CALR | 82/418 (20) | 1 (0.6) | 8 (4) | 73 (8) | |

| MPL | 37/418 (9) | 0 | 7 (4) | 30 (3) | |

| HMR | 73/418 (17) | 5/51 (10) | 9/65 (14) | 59/365 (16) | 0.45 |

| Other Mol. Mut., N (%) | 146 (35) | 16/51 (31) | 15/65 (23) | 115/365 (31) | |

| Blasts PB ≥1%, N (%) | 606 (48) | 89 (61) | 78 (44) | 439 (46) | 0.002 |

| Blasts BP 10-19%, N (%) | 56 (4) | 10 (7) | 8 (4) | 38 (4) | |

| DIPSS, N (%) Low | 1 (0.6) | 6 (3) | 98 (10) | 0.0001 | |

| Int-1 | 57 (39) | 81 (46) | 505 (52) | ||

| Int-2 | 63 (43) | 69 (39) | 239 (25) | ||

| High | 24 (17) | 20 (11) | 105 (11) | ||

| AML transformation, N (%) | 140 (11) | 17 (12) | 17 (10) | 106 (11) | 0.78 |

| SCT, N (%) | 96 (8) | 11 (8) | 17 (10) | 68 (7) | 0.71 |

| Median follow-up, months (range) | 27 (5-251) | 12 (2-134) | 23 (1-172) | 29 (10-251) | <0.001 |

Table 2.

Comparison of patients with low platelets, stratified by diagnosis

| plt < 50 | plt 50-100 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DX | PMF, N 118 | PPV-MF, N 17 | PET-MF, N 10 | PMF, N 137 | PPV-MF, N 32 | PET-MF, N 7 |

| Males, N (%) | 75 (64) | 12 (71) | 4 (40) | 101 (74) | 22 (69) | 4 (57) |

| Median age, years (range) | 68 (27-88) | 70 (32-85) | 64 (44-77) | 67 (17-84) | 70 (49-89) | 74 (68-77) |

| Age below 65 yrs, N (%) | 49 (41) | 4 (24) | 5 (50) | 59 (43) | 8 (25) | 0 |

| Median hgb (g/dL) | 9.1 (5-16) | 9 (6.4-14) | 8.9 (7-11) | 10 (6-17) | 10 (5-15) | 9 (8-13) |

| Hgb < 10 (g/dL), N (%) | 79 (67) | 11 (65) | 8 (80) | 70 (51) | 17 (53) | 5 (71) |

| Median WBC (×109/L) | 6.6 (0-228) | 15 (1-191) | 4.3 (2-35) | 7 (2-200) | 9 (3-49) | 7 (5-46) |

| WBC > 25 (×109/L), N (%) | 18 (15) | 8 (47) | 1 (10) | 20 (15) | 8 (25) | 2 (29) |

| PRBC transfusions, N (%) | 82 (69) | 4 (24) | 4 (40) | 51 (37) | 13 (41) | 3 (43) |

| Fibrosis grade ≥2, N (%) | 90 (76) | 14 (82) | 7 (70) | 109 (80) | 26 (81) | 6 (86) |

| Spleen > 5 cm [BCM], N (%) | 54 (46) | 12 (71) | 7 (70) | 68 (50) | 13 (41) | 3 (43) |

| Symptoms, N (%) | 86 (73) | 13 (76) | 7 (70) | 104 (76) | 28 (88) | 5 (71) |

| Abnormal karyotype, N (%) | 52 (44) | 10 (59) | 5 (50) | 48 (35) | 19 (59) | 1 (14) |

| Unfavorable karyotype, N (%) | 32 (27) | 4 (24) | 3 (30) | 12 (9) | 8 (25) | 1 (14) |

| JAK2 mutation, N (%) | 48 (41) | 14 (82) | 4 (40) | 68 (50) | 26 (81) | 3 (43) |

| Blasts PB ≥1%, N (%) | 70 (59) | 12 (71) | 7 (70) | 61 (45) | 15 (47) | 2 (29) |

| Blasts BP 10-19%, N (%) | 9 (7) | 0 | 1 (10) | 5 (4) | 3 (9) | 1 (14) |

| AML transformation, N (%) | 13 (11) | 0 | 4 (40) | 13 (10) | 3 (9) | 1 (14) |

| DIPSS score, N (%) Low | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 5 (4) | 1 (3) | 0 |

| Int-1 | 50 (42) | 5 (29) | 2 (20) | 67 (50) | 12 (38) | 2 (29) |

| Int-2 | 51 (42) | 5 (29) | 7 (70) | 52 (37) | 14 (44) | 3 (43) |

| high | 16 (14) | 7 (41) | 1 (10) | 13 (10) | 5 (16) | 2 (29) |

Comments and Abbreviations for Table 1 and 2: statistically significant differences (<0.05) are shown in bold, Hgb = hemoglobin, WBC = white blood cells, PRBC = packed red blood cells transfusions (at least 6 units of PRBC in the 12 weeks periods, for a hemoglobin level of <8.5 g/dL), fibrosis grading is according to European classification BCM = below costal margin, Abnormal karyotype = other than diploid, Unfavorable karyotype = as defined in DIPSS plus risk scoring system, Complex karyotype = 3 or more unrelated abnormalities, Mol. Mut. = molecular mutations, HMR = high molecular mutations (ASXL1, EZH2, IDH1, IDH2), PB = peripheral blood, DIPSS = Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System, AML = acute leukemia, SCT = allogeneic stem cell transplantation

Median platelet count in these groups (plt 50, plt 50-100 and plt 100) was 27 (range, 1-50), 77 (range, 52-100), and 278 (range, 101-2690), respectively. In general, plt 50 group was older, and had highest rate of anemia, transfusion dependency, blood and bone marrow blasts, unfavorable and complex (3 or more abnormalities) karyotype, and the highest rate of progression to acute leukemia (AML) (Tables 1 and 2, and Supplemental Table 1). Sub-analysis of patients with low platelets (plt 50 and plt 50-100) stratified by diagnosis (Table 2), revealed that patients with PPV-MF had the highest white cell counts in both groups, while those with PMF and plt 50 were most anemic and had the largest spleen. Other clinical features did not differ among groups.

In regards to therapy, 15% (n=185) of patients were not treated for their disease during their follow-up. Among those treated (n=1084), 55% (n=593) received one or two therapies, most often hydroxyurea (n=501), immunomodulatory agents (n=261), and JAK2 inhibitor ruxolitinib (n=328). Overall, 96 patients (8%) underwent allogeneic SCT with similar proportional distribution among groups (73 PMF: plt <50 and 50-100 in 9 and 15 patients; 9 PPV-MF: plt < 50 and 50-100 in 1 and 2; 14 PET-MF: plt < 50 in 1 patient; respectively).

Among patient exposed to ruxolitinib, only 3% and 10% (n=11 and n=32) were in plt 50 and plt 50-100 groups, respectively, which was significantly lower than for plt 100 group (87%, n=285; both p < 0.005).

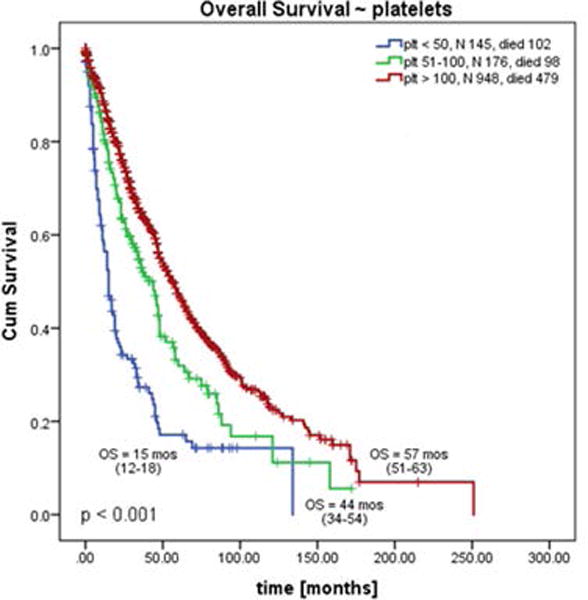

The overall median follow-up time from presentation to our institution was 27 months (range, 5-251), and was the shortest for plt 50 group (12 months, p<0.001). Median OS for plt 50 vs plt 50-100 vs plt 100 groups, was 15 vs 44 vs 57 months, respectively (p<0.001, Figure 1; plt 50 vs plt 100: HR 2.80; 95% CI 2.25-3.47; plt 50-100 vs plt 100: HR 1.4; 95% CI 1.15-1.78).

Figure 1.

Sub-analysis of newly diagnosed patients (n=678) confirmed this observation, with OS for plt 50 vs plt 50-100 vs plt 100 groups of 15, 44 and 64 months, respectively (p < 0.001, Figure 1b, Suppl. Table 2). We also compared survival difference between patients with plt above and below 100 (combined patients with plt 50 and plt 50-100). The OS of patients with plt below 100 was inferior to those with plt above 100 with 1.7-fold increased risk of death (26 vs 57 months, p < 0.001, HR 1.7 (95% CI 1.37-2).

Analyses of OS for patients with PMF, PPT-MF and PET-MF within the same plt group showed differences among patients with plt 50 and plt 100. PET-MF patients had the shortest OS in plt 50 group (PMF vs PPV-MF vs PET-MF; median OS = 15 vs 20 vs 6 months, respectively; p = 0.003), but the longest in plt 100 group (50 vs 64 vs 79 months, p < 0.001). No difference was noticed among those with plt 50-100 group (44 vs 36 vs 36 months, p=0.63, Supplemental Table 2, graphs not shown).

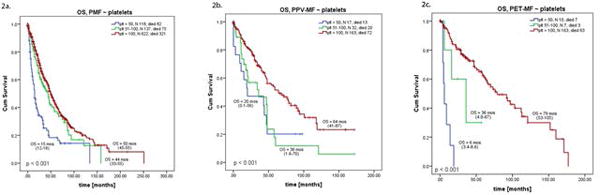

Analyses of OS based on plt level within each disease entity showed differences. Among PMF patients, plt 50 had significantly worse OS than all others, but OS for plt 50-100 was similar to plt 100 (15 vs 44 vs 50 months, respectively, overall p<0.001; but p=0.36 for plt 50-100 vs plt 100; Figure 2a). Survival censored for SCT confirmed our findings with respective OS of 13 vs 31 vs 47 months (plt 50 vs 50-100 vs 100; data not shown).

Figure 2.

Similar results were found when OS was adjusted per International Prognostic Scoring System or Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System risk scores in newly diagnosed or all patients, respectively (Supplemental Table 2).

Further stratification of patients with PPV-MF and PET-MF showed them to have inferior OS once their platelets drops below 100 (plt 50-100 vs plt 100, p<0.001 for both groups, Figure 2b, 2c); further decrease to below 50 significantly worsened OS in patients with PET-MF (plt 50 vs plt 50-100, p<0.01). Respective OS after censoring for SCT (plt 50 vs 50-100 vs 100) were 20 vs 34 vs 59 months for PPV-MF, and 6 vs 17 vs 76 months for PET-MF (confirmatory findings, data not shown).

Stratification of patients with PPV-MF and PET-MF according to Myelofibrosis Secondary to PV and ET - Prognostic Model (MYSEC-PM) (20) wasn’t possible due to small number of patients in low platelet subgroups and low to intermediate 2 MYSEC-PM risk groups.

Sub-analysis including only newly diagnosed patients confirmed our above observations with only one exception: among PET-MF patients both plt 50 and plt 50-100 had very poor OS (6 months for both groups, Supplemental Table 3).

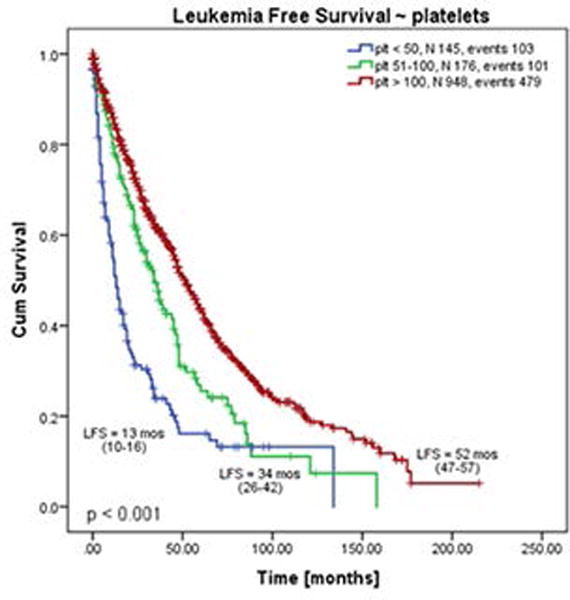

During an observation period of 3849 person-years, 140 (11%) patients had progressed to AML, with an incidence of 3.6 cases per 100 person-years. The incidence of AML in plt 50-100 and plt 100 groups was similar to overall incidence (3.6 and 3.4 cases per 100 person-years, respectively). However, incidence of AML was almost doubled in plt 50 group (6.9 cases per 100 person-years). In line with this results, leukemia free survival (LFS) was the shortest in plt 50 group: median LFS for plt 50 vs plt 50-100 vs plt 100 groups was 13 vs 34 vs 52 months, respectively (p < 0.001, Figure 3). LFS at one year (plt 50 vs plt 50-100 vs plt 100) was 55% vs 78% vs 85%, and at 3 years 23% vs 48% vs 61%, respectively. When stratified according to the diagnosis, the shortest LFS was seen in patients with PET-MF and plt 50 (6 months), and the longest in PET-MF and plt 100 (76 months). During the entire follow-up, 51% (n=652) patients died, with the highest rate among those with plt 50 (plt 50 vs plt 50-100 vs plt 100: 70% vs 55% vs 48%, respectively).

Figure 3.

Discussion

Thrombocytopenia (platelets <100 ×109/L) is seen in patients with MF, with an overall incidence around 26% (1). Severe thrombocytopenia (platelets < 50 ×109/L) occurs overall in about 11-16% of patients with MF, and only in 2-6% of those with PET/PPV-MF (21), which is consistent with our results. Significance of thrombocytopenia (platelets <100 ×109/L) has been addressed by incorporating it into the Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System Plus (DIPSS-plus) (12), where it independently predicted inferior overall and leukemia free survival, with an actual 1.4-fold increased risk of death.

However, recent reports (14, 15, 22, 23) suggested that patients with severe thrombocytopenia (<50 ×109/L) have particularly short survival. Tam et al. has previously reported poor OS (<12 months) of patients with MF and platelets < 50 ×109/L, and considered it as one of the features of accelerated phase (AP) of MF alongside elevated blasts ≥ 10%, and chromosome 17 aberrations, with respective median OS of 12, 10, and 5 months. Forty and 39 patients with PPV-MF and PET-MF were included in this analysis with a median OS of 12 months in the presence of one of the aforementioned factors for AP.

Hernandez and colleagues (15) reported on a group of 57 patients with severe thrombocytopenia (41 PMF, 16 PET/PPV-MF) that had adverse clinical features, such as higher age, lower hemoglobin and absolute neutrophil count, higher blasts and higher fibrosis, higher DIPSS risk score, more cytogenetic abnormalities, as well as higher progression rate to AML, than other patients, with a median survival of 2.2 years.

Our study confirmed the adverse clinical features as well as poor OS and LFS in these patients in the largest cohort of patients reported so far. Furthermore, we compared the impact of low platelets on the outcome of patients with PMF vs PPV-MF vs PET-MF, since it has been shown that these patients differ in their clinical characteristics and OS (24).

Similar to what was reported by Hernandez et al, we found that plt 50 group is the most anemic and transfusion dependent, but this was mostly present in those with PMF. While plt 50 group had the highest blast count and unfavorable karyotype, the highest progression rate to AML was seen in those with PET-MF and plt 50. On the other hand, PET-MF patients in plt 100 group had the longest OS and LFS. In contrast to results published by Hernandez et al (15), we did not find the highest rate of high DIPSS score, lower neutropenia, and higher fibrosis grade in plt 50 group, vs others, nor were these patients the oldest.

Consistent with other reports, we have confirmed that patients with platelet 50 have the shortest OS. Risk of death was increased in patients with platelets 50 and those with platelets between 50-100 when compared to those with platelets above 100 by 2.8 and 1.4-fold, respectively. When compared to standard separation of patients by platelet cutoff of 100, where the risk of death has increased in patients with thrombocytopenia by 1.7-fold (consistent with DIPSS Plus score of 1.4-fold), patients with platelets below 50 clearly represent group with shortest survival.

However, this uniform separation may not have similar significance in patients with PMF and PET/PPV-MF, or at the time of diagnosis versus during the disease course. Patients with platelets below 50 and PMF confer the worst prognosis with inferior survival to those with platelets above 50, and therefore platelet cutoff of 50 (rather than 100 as in DIPSSplus) may better distinguish this high risk group of patients. This was observed at the time of diagnosis in only newly diagnosed patients, as well as during the course of disease.

On the contrary, even despite the small number of patients with PPV/PET-MF, the predictive value of platelets below 50 for inferior survival was not largely seen. Patients with PPV-MF and platelets of 50 and 50-100 have similar OS, which was inferior to those with platelets above 100, and it was observed at the time of diagnosis as well as during the disease course. This observation is in line with our previous report, that severe thrombocytopenia does not play such an important role in inferior OS of patients with PPV-MF (24). Patients with PET-MF and platelets of 50-100 had significant worse OS than those with platelets above 100 at the time of diagnosis as well as during the disease course. Patients with PET-MF and platelets below 50 had significantly worse OS than all remaining patients only during the course of the disease, however, the results need to be interpreted with caution due to the small number of patients. Paucity of data on this topic in the literature, likely due to very low incidence of severe thrombocytopenia in these patients and their poor outcome, enables us to compare our results to others. Even comparison to existing data is limited; Hernandez et al. have not separately reported on the outcome of patients with PET/PPV-MF, and even though Tam et al. reported median OS of 12 months in patients with PET/PPV-MF and platelets below 50, it combines both diagnoses together leaving the differences between PPV-MF and PET-MF patients unknown. Furthermore, Tam reported OS for entire defined AP of MF (presence of any of the risk factors, e.g platelets < 50, blasts ≥10% or abnormality of chromosome 17). Considering the overall dismal outcome of patients with AP or abnormalities of chromosome 17, the clear impact of the low platelet in this study is hard to see.

Treatment with specific therapy such as JAK2 inhibitor, ruxolitinib, was observed in minority of patients with platelets below 100, which is in line with previous reports. Although JAK2 inhibitors are not approved for patients with severe thrombocytopenia, there are case reports and series in which JAK2 inhibitors have been used successfully with improvement of platelet count (25, 26). However, for the majority of patients, the management of severe thrombocytopenia remains an unmet need, and future studies focused on patients with low platelets are deeply needed, to extend their extremely limited treatment armamentarium. Consequently, allogenic stem cell transplantation should be offered to all eligible patients to alter the disease course.

A major limitation of our study is its retrospective character, data from a single center, and limited number of patients in sub-analyses. A large, prospective, multicenter study should be performed to improve our understanding of the biology of the disease, and identify the most reliable factors and sings of progression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant CA016672 from the National Cancer Institute (National Institutes of Health).

Footnotes

DR. LUCIA MASAROVA (Orcid ID : 0000-0001-6624-4196)

DR. AHMAD ALHURAIJI (Orcid ID : 0000-0002-4669-0233)

Author contributions: LM, AA and SV reviewed patient’s charts, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. LM and AA claim equal contribution to this manuscript. SP provided patient’s data. PB, ND, NP, JC, HK SV treated patients, and reviewed the manuscript. All authors participated in the discussion, have reviewed and approved the final version.

Disclosure of conflicts of interest: None.

References

- 1.Mesa RA, Silverstein MN, Jacobsen SJ, Wollan PC, Tefferi A. Population-based incidence and survival figures in essential thrombocythemia and agnogenic myeloid metaplasia: an Olmsted County Study, 1976-1995. American journal of hematology. 1999;61(1):10–5. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8652(199905)61:1<10::aid-ajh3>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reilly JT, McMullin MF, Beer PA, Butt N, Conneally E, Duncombe A, et al. Guideline for the diagnosis and management of myelofibrosis. Br J Haematol. 2012;158(4):453–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith RE, Chelmowski MK, Szabo EJ. Myelofibrosis: a review of clinical and pathologic features and treatment. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 1990;10(4):305–14. doi: 10.1016/1040-8428(90)90007-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lataillade JJ, Pierre-Louis O, Hasselbalch HC, Uzan G, Jasmin C, Martyre MC, et al. Does primary myelofibrosis involve a defective stem cell niche? From concept to evidence. Blood. 2008;112(8):3026–35. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-158386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pikman Y, Lee BH, Mercher T, McDowell E, Ebert BL, Gozo M, et al. MPLW515L is a novel somatic activating mutation in myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. PLoS medicine. 2006;3(7):e270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tefferi A. Pathogenesis of myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(33):8520–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.9316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tefferi A, Mesa RA, Schroeder G, Hanson CA, Li CY, Dewald GW. Cytogenetic findings and their clinical relevance in myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. Br J Haematol. 2001;113(3):763–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benetatos L, Chaidos A, Alymara V, Vassou A, Bourantas KL. Combined treatment with thalidomide, corticosteroids, and erythropoietin in patients with idiopathic myelofibrosis. European journal of haematology. 2005;74(3):273–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2004.00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verstovsek S, Mesa RA, Gotlib J, Levy RS, Gupta V, DiPersio JF, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;366(9):799–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Begna KH, Patnaik MM, Zblewski DL, Finke CM, et al. A Pilot Study of the Telomerase Inhibitor Imetelstat for Myelofibrosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;373(10):908–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deeg HJ, Bredeson C, Farnia S, Ballen K, Gupta V, Mesa RA, et al. Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation as Curative Therapy for Patients with Myelofibrosis: Long-Term Success in all Age Groups. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gangat N, Caramazza D, Vaidya R, George G, Begna K, Schwager S, et al. DIPSS plus: a refined Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System for primary myelofibrosis that incorporates prognostic information from karyotype, platelet count, and transfusion status. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(4):392–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patnaik MM, Caramazza D, Gangat N, Hanson CA, Pardanani A, Tefferi A. Age and platelet count are IPSS-independent prognostic factors in young patients with primary myelofibrosis and complement IPSS in predicting very long or very short survival. European journal of haematology. 2010;84(2):105–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alhuraiji AML, Bose P, Daver NG, Cortes JE, Pierce S, Kantarjian HM, Verstovsek S. Clinical features and outcome of patients with poor-prognosis myelofibrosis based on platelet count <50 × 109/L: A single-center experience in 1100 myelofibrosis patients. JCO. 2016;(suppl. 15):7068. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hernandez-Boluda JC, Correa JG, Alvarez-Larran A, Ferrer-Marin F, Raya JM, Martinez-Lopez J, et al. Clinical characteristics, prognosis and treatment of myelofibrosis patients with severe thrombocytopenia. British journal of haematology. 2017 doi: 10.1111/bjh.14601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127(20):2391–405. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barosi G, Mesa RA, Thiele J, Cervantes F, Campbell PJ, Verstovsek S, et al. Proposed criteria for the diagnosis of post-polycythemia vera and post-essential thrombocythemia myelofibrosis: a consensus statement from the International Working Group for Myelofibrosis Research and Treatment. Leukemia. 2008;22(2):437–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gianelli U, Vener C, Bossi A, Cortinovis I, Iurlo A, Fracchiolla NS, et al. The European Consensus on grading of bone marrow fibrosis allows a better prognostication of patients with primary myelofibrosis. Mod Pathol. 2012;25(9):1193–202. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luthra R, Patel KP, Reddy NG, Haghshenas V, Routbort MJ, Harmon MA, et al. Next-generation sequencing-based multigene mutational screening for acute myeloid leukemia using MiSeq: applicability for diagnostics and disease monitoring. Haematologica. 2014;99(3):465–73. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.093765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Passamonti F, Giorgino T, Mora B, Guglielmelli P, Rumi E, Maffioli M, et al. A clinical-molecular prognostic model to predict survival in patients with post polycythemia vera and post essential thrombocythemia myelofibrosis. Leukemia. 2017 doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hernandez-Boluda JC, Pereira A, Gomez M, Boque C, Ferrer-Marin F, Raya JM, et al. The International Prognostic Scoring System does not accurately discriminate different risk categories in patients with post-essential thrombocythemia and post-polycythemia vera myelofibrosis. Haematologica. 2014;99(4):e55–7. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.101733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tam CS, Kantarjian H, Cortes J, Lynn A, Pierce S, Zhou L, et al. Dynamic model for predicting death within 12 months in patients with primary or post-polycythemia vera/essential thrombocythemia myelofibrosis. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(33):5587–93. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.8833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tefferi A, Pardanani A, Gangat N, Begna KH, Hanson CA, Van Dyke DL, et al. Leukemia risk models in primary myelofibrosis: an International Working Group study. Leukemia. 2012;26(6):1439–41. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masarova L, Bose P, Daver N, Pemmaraju N, Newberry KJ, Manshouri T, et al. Patients with post-essential thrombocythemia and post-polycythemia vera differ from patients with primary myelofibrosis. Leukemia research. 2017;59:110–6. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Talpaz M, Paquette R, Afrin L, Hamburg SI, Prchal JT, Jamieson K, et al. Interim analysis of safety and efficacy of ruxolitinib in patients with myelofibrosis and low platelet counts. Journal of hematology & oncology. 2013;6(1):81. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-6-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bjorn ME, Holmstrom MO, Hasselbalch HC. Ruxolitinib is manageable in patients with myelofibrosis and severe thrombocytopenia: a report on 12 Danish patients. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57(1):125–8. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2015.1046867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.