Tissue hypoxia decreases in mouse aortic valves after birth, and exposure to hypoxia promotes glycosaminoglycan accumulation in cultured chicken embryo valves and adult murine heart valves. Thus, hypoxia maintains a primitive extracellular matrix in during heart valve development and promotes extracellular matrix remodeling in adult mice, as occurs in myxomatous disease.

Keywords: heart valve development, hypoxia, extracellular matrix, glycosaminoglycans, Sox9

Abstract

During postnatal heart valve development, glycosaminoglycan (GAG)-rich valve primordia transform into stratified valve leaflets composed of GAGs, fibrillar collagen, and elastin layers accompanied by decreased cell proliferation as well as thinning and elongation. The neonatal period is characterized by the transition from a uterine environment to atmospheric O2, but the role of changing O2 levels in valve extracellular matrix (ECM) composition or morphogenesis is not well characterized. Here, we show that tissue hypoxia decreases in mouse aortic valves in the days after birth, concomitant with ECM remodeling and cell cycle arrest of valve interstitial cells. The effects of hypoxia on late embryonic valve ECM composition, Sox9 expression, and cell proliferation were examined in chicken embryo aortic valve organ cultures. Maintenance of late embryonic chicken aortic valve organ cultures in a hypoxic environment promotes GAG expression, Sox9 nuclear localization, and indicators of hyaluronan remodeling but does not affect fibrillar collagen content or cell proliferation. Chronic hypoxia also promotes GAG accumulation in murine adult heart valves in vivo. Together, these results support a role for hypoxia in maintaining a primitive GAG-rich matrix in developing heart valves before birth and also in the induction of hyaluronan remodeling in adults.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Tissue hypoxia decreases in mouse aortic valves after birth, and exposure to hypoxia promotes glycosaminoglycan accumulation in cultured chicken embryo valves and adult murine heart valves. Thus, hypoxia maintains a primitive extracellular matrix during heart valve development and promotes extracellular matrix remodeling in adult mice, as occurs in myxomatous disease.

INTRODUCTION

The period just after birth in mammals is characterized by the transition to the normoxia of atmospheric air (33). Physiological changes in blood circulation and lung development also lead to increased oxygenation of tissues in the postnatal period. At the same time, semilunar and atrioventricular valves of the heart undergo elongation of valve leaflets, reduction of valve interstitial cell (VIC) proliferation, and stratification of the extracellular matrix (ECM) (13). Primitive mouse valves in utero and chicken embryo valves in ovo are composed primarily of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) and express the chondrogenic transcription factor Sox9 (18, 19). The mature valve leaflet ECM consists of stratified fibrillar collagen deposition in the fibrosa layer, GAG expression in the spongiosa, and elastin in the atrialis/ventricularis layer (14). In the present study, the effects of hypoxia on maintaining GAG-rich primitive valve matrix in immature valves were examined in mouse embryos and chicken embryo explanted aortic valve cultures.

Postnatal heart valve development is characterized by ECM changes that include accumulation of distinct classes of GAGs, including hyaluronan (HA), that change relative to collagen expression over time. The specific composition of GAGs is critical to normal valve function and, when dysregulated, also contributes to pathological remodeling in calcific and myxomatous valve disease (10). The prenatal primitive valve matrix is characterized by HA, which is the predominant GAG in the endocardial cushions, the embryonic valve precursors (14). At late fetal and early postnatal stages, valve stratification is characterized by expression of cartilage-like chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans in the spongiosa and collagen type 1 and 3 fibers of the fibrosa (13). The main proteoglycans in mature valves include versican, biglycan, and decorin, which are associated with compressibility and elasticity of mature valve leaflets (9). In addition to matrix changes, VIC proliferation decreases and valve leaflets elongate after birth in mice and hatching in chicks (13, 18). In myxomatous valve disease (MVD), there is disruption and disorganization of elastin and collagen matrixes with increased accumulation of GAGs and HA remodeling, which is the reverse of postnatal valve maturation (9, 10, 16). The driving forces in postnatal valve stratification and myxomatous degeneration are not well characterized.

After birth, the transition to atmospheric oxygen affects the maturation of multiple organ systems, including the heart (24). Indicators of hypoxia are detected in many embryonic and fetal tissues of mice in utero and chickens in ovo (3, 31). Thus, tissue hypoxia is associated with immature phenotypes of many cell lineages. In cardiomyocytes, exposure to hypoxia in the days after birth promotes proliferation and maintenance of an immature phenotype including regenerative potential (24). Moreover, exposure of adult mice to hypoxia promotes cardiac regeneration after myocardial infarction (22). In cartilage, hypoxia promotes chondrogenic differentiation, including induction of the transcription factor Sox9 and proteoglycans (3, 25). Hypoxia also increases the accumulation of HA, the synthetic enzyme HA synthase 2 (HAS2), and the degrading enzyme hyaluronidase 2 (Hyal2), indicative of HA remodeling in avascular tumor cells and cartilage (7, 12). The role of hypoxia in heart valve development has not previously been reported, but, like chondrocytes, immature heart valves are characterized by high GAG content under prenatal conditions. In addition, the effects of exposure to atmospheric O2 (21% O2) after birth on valve maturation are not known. Likewise the role for tissue hypoxia in ECM remodeling during heart valve disease is unclear.

In the present study, we examined aortic valve ECM maturation, HA remodeling, VIC proliferation, and Sox9 expression relative to tissue hypoxia indicators in mice at postnatal days 1−30 (P1−P30). The ability of hypoxic conditions to promote VIC proliferation, collagen fiber formation, HA remodeling, and Sox9 expression was examined in chicken embryonic day 14 (E14) aortic valve organ cultures. The effects of hypoxia on adult heart valve ECM remodeling were evaluated in adult mice exposed to chronic hypoxia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and hypoxyprobe-1 injections.

All mouse experiments conformed with National Institutes of Health guidelines (Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals) and were performed with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Cincinnati Children’s Research Foundation or University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Wild-type C57BL/6J mice purchased from Jackson Laboratory were bred to produce litters of mice for analysis of progeny at P1–P30. The day of birth is considered to be P0. Mice were euthanized at P1, P7, or P30 under isoflurane inhalation followed by cervical dislocation at the specified time point for each experiment. To monitor cellular hypoxia, mice were intraperitoneally injected with 60 mg/kg hypoxyprobe-1 (HP-1; HP1-1000 kit) dissolved in saline solution 90 min before death as previously described (29). Adult (2 mo old) C57/B6J mice were subjected to a gradual reduction of inhaled O2 (1% decrease per day over the course of 2 wk) followed by maintenance at 7% O2 (hypoxia) for 2 wk compared with normoxia control mice, as previously described by Nakada et al. (22). Male and female mice were used for all analyses, and no significant differences between sexes were observed.

Chicken embryos and E14 aortic valve organ cultures.

Fertilized white leghorn chicken eggs were purchased from Charles River Laboratories and incubated on site at 38°C. All chicken embryo experiments conformed with National Institutes of Health guidelines (Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals) and were performed with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Cincinnati Children’s Research Foundation. Embryos were killed by decapitation at E14−E18. Hearts were isolated for histology or mRNA isolation. Alternatively, aortic roots with valve leaflets were cultured intact as chicken aortic valve organ cultures (cAVOCs) as previously described (6). cAVOCs were cultured in medium 199 (CellGro) supplemented with 10% FBS (HyClone) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Life Technologies). Cultures were incubated under hypoxic conditions (1% O2) in a HypOxystation H35 (HypOxygen) or at 21% O2 in a tissue culture incubator. One-half of the media was replaced with fresh media after 2 days for all cultures. To monitor hypoxia, 200 μM HP-1 (Fisher Scientific) was added to the media 90 min before cells were harvested. cAVOCs were collected after 4 days in culture for histological, RNA, or protein analysis.

Histology and immunofluorescence labeling.

Murine hearts, chicken embryo hearts, or cAVOCs were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, cleared in xylenes, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 5 μm. Movat’s pentachrome staining (American MasterTech) and sirius red staining (Sigma-Aldrich) were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Alcian blue staining was used to quantify GAG content. Samples were placed in 3% glacial acetic acid for 3 min, transferred into 1% alcian blue solution (Movat’s pentachrome staining kit, American MasterTech) for 30 min, rinsed in distilled water, and dehydrated through ethanol series. Stained specimens were cleared in xylene and mounted with cytoseal (Electron Microscopy Science). For immunofluorescence experiments, sectioned specimens were pretreated for 5 min using citric acid antigen retrieval (Vector Laboratories) in a pressure cooker as previously described (2). The following primary antibodies were used: phosphohistone H3 (pHH3; no. 06570, Millipore, 1:300), Sox9 (no. AB5535, Millipore, 1:300), hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α; PA1-16601, Thermo Scientific, 1:100), HA-binding protein (HABP; no. 385911, Millipore, 1:100), and Hyal2 (ab68608, Abcam, 1:300). For fluorescent detection, Alexa Fluor 568- or Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibodies were used at 1:500 dilution. For TUNEL staining, an in situ cell death detection kit (Roche Applied Science) was used following the manufacturer’s protocol. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Life Technologies, 1:10,000).

Microscopic images were captured using a Nikon A1-R confocal system with NIS-Elements D 3.2 software. TUNEL-, Sox9-, and pHH3-positive nuclei were counted as a a percentage of total nuclei for each valve leaflet. The HABP-positive area was measured and reported relative to total leaflet area. The integrity of the collagen network was determined with picrosirius red polarization microscopy to quantify the ratio of birefringence between thick closely packed mature collagen fibers, indicated by orange-red fluorescence, and loosely packed less cross-linked and immature collagen fibers, indicated by yellow-green fluorescence. For samples, n = 5 was used for each developmental stage for mice, n = 3 for chronic hypoxia or normoxia in adult mice, and n = 7 cAVOCs were assessed per condition.

For HP-1 detection, primary antibody (HP-1; HP1-1000 kit, 1:100) was used, detected with the ultrasensitive ABC mouse IgG staining kit (Thermo Scientific), and visualized with diaminobenzidine. The positive area was determined using NIS Elements Basic Research software (Nikon). Quantification of color pixel intensity was determined using NIS Elements Basic Research software (Nikon). Color pixel intensity cutoff values were set and then applied to determine the percentage of positive pixels in cAVOC sections as previously described. At least five independent individuals (n = 5) were analyzed for murine experiments and at least seven cAVOCs (n = 7) were analyzed per condition.

RNA isolation and real-time quantitative PCR.

For RNA isolation, aortic valves from three mice were pooled together for each biological sample where both leaflets and root were isolated together for P1, whereas leaflets alone were isolated for P7 and P30. For chicken experiments, five to seven cAVOCs were pooled together per biological sample. Total RNA was purified using the NucleoSpin RNA/Protein extraction kit (Macherey-Nagel) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcriptions were performed using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen) as previously described (15). Quantitative real-time PCR analyses were performed using Taqman probes (Applied Biosystems) for mouse and SYBR green primer sequences for the mouse and chicken (Table 1). Level changes were calculated using the ΔΔCT method (where CT is threshold cycle) using β2-microglobulin or 28S for normalization in the mouse and chicken, respectively (6). The average of control samples (P1 for murine samples and 21% O2 for cAVOCs) was then set to 1 for each gene. For murine samples, n = 6 biological samples were used per condition. For cAVOCs, 10 biological samples were analyzed per condition. All primers were designed using the National Center for Biotechnology Information primer design system and were tested for specificity before RT-PCR amplification.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for quantitative PCR

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse primers | ||

| B2M | Mm00437762 | |

| Col1a1 | Mm00801666 | |

| Col3a1 | Mm01254476 | |

| Sox9 | Mm00448840 | |

| Hsp47 | 5′-TTTTGTCACCATGCCCCGAG-3′ | 5′-CATTTTAAGGATGGGCAGTTCTGGG-3′ |

| Dcn | 5′-GAAGCGGTAACGAGCAGCA-3′ | 5′-AATGGTCCAGCCCAAGAGAC-3′ |

| Has2 | 5′-GACCCTATGGTTGGAGGTGTTG-3′ | 5′-ACGCTGCTGAGGAAGGAGATC-3′ |

| Hyal2 | 5′-CGAGGACTCACGGGACTGA-3′ | 5′-GGCACTCTCACCGATGGTAGA-3′ |

| Id2 | 5′-CTTCCTCCTACGAGCAGCAT-3′ | 5′-TGGTCCGACAGGCTGTTTTT-3′ |

| Glut1 | 5′-CCAGCTGGGAATCGTCGTT-3′ | 5′-TGCATTGCCCATGATGGAGT-3′ |

| Ctgf | 5′-ACATGGCGTAAAGCCAGGAA-3′ | 5′-TCTCGCTAGAGCAGGTCTGT-3′ |

| Chicken primers | ||

| Id2 | 5′-TCCCTACAGGCAGCCGAGT-3′ | 5′-TAGCGTGGATTCCTCCCCTC-3′ |

| Glut1 | 5′-AAGACTTCTACAACCACACCTG-3′ | 5′-AAAGAGTCCCACGGAAAAGG-3′ |

| Ctgf | 5′-TCAGACCTTGCGAAGCTGAC-3′ | 5′-TCTGTACGTCTTCACGCTGG-3′ |

| Col1a1 | 5′-ACGGCTTCCAGTTTGAGTAC-3′ | 5′-TGTTCTTGCAGTGGTAGGTG-3′ |

| Col3a1 | 5′-ATGCTTGTGGCTGAGTTCTGT-3′ | 5′-TGGGTACATCCTCCTAGGGC-3′ |

| 28S | 5′-GGCCCCAAGACCTCTAATC-3′ | 5′-CGGGTATAGGGGCGAAAGAC-3′ |

B2M, β2-microglobulin; Col1a1, collagen type 1a1; Col3a1, collagen type 3a1; Hsp47, heat shock protein 47; Dcn, decorin; Has2, hyaluronan synthase 2; Hyal2, hyaluronidase 2; Id2, inhibitor of DNA binding 2; Glut1, glucose transporter 1; Ctgf, connective tissue growth factor.

cAVOC protein isolation and Western blot analysis.

Total protein was isolated from cAVOCs (5–7 cAVOCs pooled for each biological sample) simultaneously with RNA isolation using the NucleoSpin RNA/Protein extraction kit (Macherey-Nagel). Western blots were performed as previously described (8). Primary antibodies used were Hyal2 (ab68608, Abcam, 1:500) and β-actin (no. 5316, Abcam, 1:1,000), which were detected with the secondary antibodies IRDye 800CW or 680RD (LI-COR). Blots were imaged using an Odyssey scanner with ImageStudio version 3.1.4 software. For samples, n = 4 independent biological samples consisting of 5–7 AVOCs/sample were analyzed per condition.

Statistics.

Unpaired t-tests with Welch’s correction or one-way ANOVA when appropriate were used to determine the significance of observed differences between the means using the PRISM7 software package (GraphPad). Data are reported as means ± SE. Statistically significant differences are reported when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

The ECM is stratified and VIC proliferation decreases during postnatal valve remodeling.

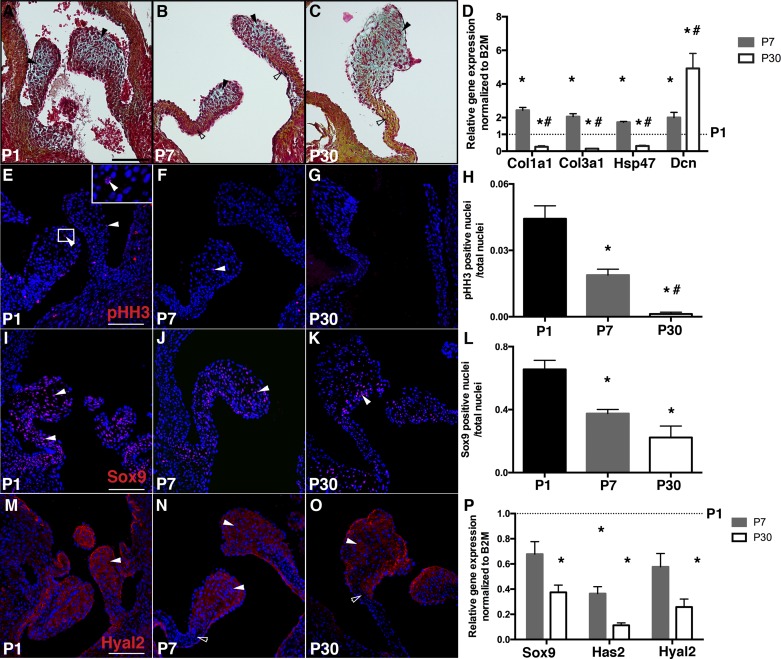

Previous studies have demonstrated decreased valve cell proliferation and increased ECM stratification at 2 wk and 4 mo after birth in mice, but the key drivers of these changes are not fully known (13). In the days after birth in mammals, the transition to atmospheric O2 is accompanied by significant changes in circulation and respiration. Postnatal aortic valve maturation was examined at early postnatal stages (P1 and P7) and also at P30 in mice. Aortic valve remodeling from P1 to P30 was characterized by leaflet thinning, elongation, and ECM stratification (Fig. 1, A–C). By Movat’s pentachrome staining, collagen expression was clearly observed at P7, in contrast to weak expression at P1, and the matrix was fully stratified by P30. Gene expression analysis of RNA isolated from aortic valves demonstrated that expression of fibrillar collagens [collagen type 1a1 (Col1a1) and collagen type 3a1 (Col3a1)] as well as the collagen-specific molecular chaperone heat shock protein 47 increased from P1 to P7 but then decreased from P7 to P30 (Fig. 1D). In contrast, expression of the short leucine-rich proteoglycan decorin, which regulates collagen fibrillogenesis (34), increased from P1 to P30. VIC proliferation, as detected pHH3 immunoreactivity, declined from P1 to P7, and very low homeostatic levels were detected at P30 (Fig. 1, E–H). Similarly, nuclear localization and mRNA expression of the transcription factor Sox9, which promotes VIC proliferation and chondrogenic gene expression (19), also declined from P1 to P30 (Fig. 1, I–L). Together, these results demonstrate a transient increase in fibrillar collagen gene expression during the first week after birth. In contrast, Sox9 and HA-related gene expression, as well as VIC proliferation, progressively decrease from P1 to P30 in aortic valve leaflets after birth.

Fig. 1.

Postnatal valve maturation is characterized by decreased cell proliferation and extracellular matrix remodeling with localized fibrillar collagen and glycosaminoglycan (GAG) expression. A–C: representative Movat’s pentachrome staining of heart sections from postnatal day 1 (P1), P7, and P30 wild-type (WT) mice indicating GAG in blue (solid arrowheads) and collagen in yellow (open arrowheads) in aortic valves. D: collagen type 1a1 (Col1a1), collagen type 3a1 (Col3a1), heat shock protein 47 (Hsp47), and decorin (Dcn) mRNA expression was measured by quantitative PCR in P7 and P30 murine aortic valves, normalized to β2-microglobulin (B2M), and compared with P1 aortic valves (set as 1, dotted line, n = 6 per time point). E–G: cell proliferation was detected by phosphohistone H3 (pHH3) staining (red nuclei) with DAPI nuclear staining (blue nuclei) of heart sections from P1, P7, and P30 WT mice. pHH3-positive nuclei are indicated by arrowheads, and the boxed region is shown at high magnification in the inset in E. H: the number of pHH3-positive nuclei/total nuclei was quantified in aortic valve leaflet sections (n = 5 per time point). I–K: representative Sox9 immunostaining (arrowheads) of heart sections from P1, P7, and P30 WT mice. L: the number of Sox9-positive nuclei/total nuclei was quantified in aortic valve leaflet sections (n = 5 per time point). M–O: representative hyaluronidase 2 (Hyal2) immunostaining of heart sections from P1, P7, and P30 WT mice. Solid arrowheads indicate GAG-rich areas; open arrowheads indicate the collagen-rich region. P: Sox9, hyaluronan synthase 2 (Has2), and Hyal2 mRNA expression levels were measured by quantitative PCR in P7 and P30 murine aortic valves, normalized to B2M, and compared with P1 aortic valves (set as 1, dotted line, n = 6 per time point). Data are reported as means ± SE. Scale bar = 100 μm. *P < 0.05 vs. P1 and #P < 0.05 vs. P7, as determined by one-way ANOVA.

While collagen maturation increased in the medial leaflet region, GAG expression became more restricted to the distal tips of the valve leaflets from P1 to P30 (Fig. 1, A–C). Has2 and Hyal2, indicators of HA homeostasis, were also decreased by P30, consistent with conversion of the HA-enriched provisional matrix to a fibrillar collagen matrix in the fibrosa layers of the aortic valve after birth (Fig. 1P). However, Hyal2 colocalization with GAGs was maintained in the distal tip region (Fig. 1, M–O, solid arrowheads) and not in the collagen-rich layer (Fig. 1, N and O, open arrowheads), consistent with stratification of mature heart valves. Thus, indicators of HA remodeling are differentially localized from newly synthesized fibrillar collagen in the weeks after birth in mice.

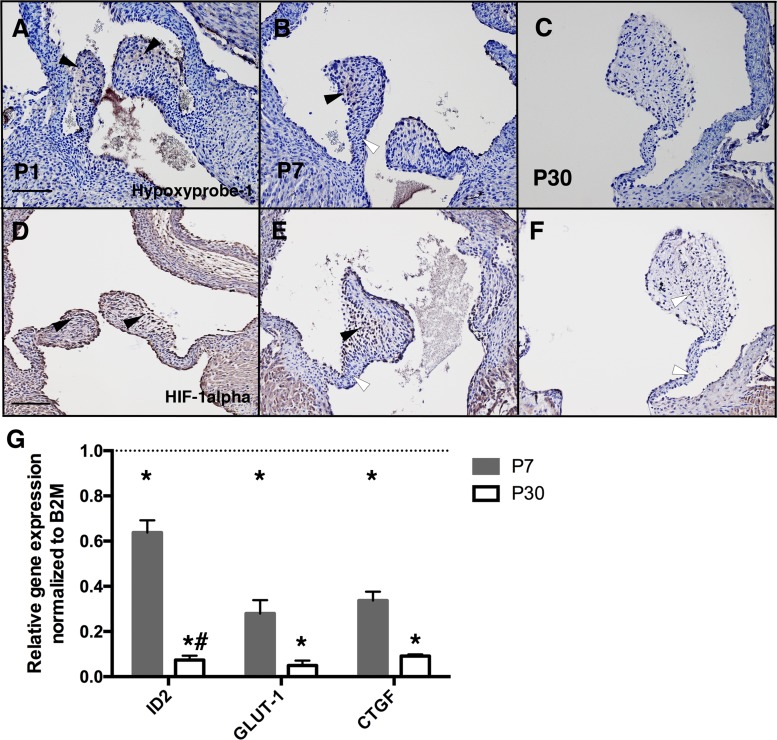

Tissue hypoxia is decreased in murine aortic valves after birth.

During the first week after birth, mammals transition from the relatively hypoxic environment in utero to independent respiration and atmospheric normoxia (24). In developing cartilage, hypoxia promotes chondrogenic differentiation evident in increased GAG expression, including increased HA (3). To determine when and where hypoxia is detected in developing heart valves soon after birth, we injected mice with HP-1 for labeling of hypoxic areas in heart valves. HP-1 detection indicated that most of the leaflet was hypoxic at P1 (Fig. 2A), in contrast to more localized hypoxia at the valve leaflet distal tips at P7 (Fig. 2B, black arrowhead), and no hypoxia was detected in P30 aortic valves (Fig. 2C, white arrowhead). Similarly, HIF-1α staining was localized throughout the valve leaflet at P1 (Fig. 2D) and localized in the tip at P7 (Fig. 2E), whereas no staining was detected at P30 (Fig. 2F). Furthermore, HIF-1α staining was observed in endothelial cells on the surface of aortic valve leaflets at P1 and P7 (Fig. 2, D and E). Expression of hypoxia-induced genes inhibitor of DNA binding 2 (Id2), glucose transporter 1 (Glut1), and connective tissue growth factor (Ctgf) (24) in aortic valve leaflets was also measured at P1, P7, and P30 (Fig. 2G). During normal postnatal maturation, expression of Id2, Glut1, and Ctgf was significantly decreased between P1 and P7, and Id2 was further significantly decreased between P7 and P30 (Fig. 2G). Thus, the levels of hypoxia, as indicated by HP-1 and HIF-1α, as well as hypoxia-responsive gene expression, are decreased in aortic valves after birth. Interestingly, at P7, hypoxia was detected at the valve distal tips (Fig. 2B, arrowhead) where GAGs and Hyal2 are localized after birth (Fig. 1, B and N, solid arrowheads). Thus, the week after birth in mice is characterized by decreasing hypoxia as well as reduced cell proliferation, Sox9 expression, and HA remodeling. At the same time, fibrillar collagen gene expression increases and the valve ECM layers become more distinct.

Fig. 2.

Hypoxic indicators in aortic valves decrease after birth in mice. A–C: representative hypoxyprobe-1 staining (black arrowheads) for heart sections from postnatal day 1 (P1), P7, and P30 wild-type (WT) mice previously injected with hypoxyprobe-1 (60 mg/kg). White arrowheads indicate nonhypoxic areas. D–F: representative hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) staining (black arrowheads) for heart sections from P1, P7, and P30 WT mice. Similar results were obtained for n = 3 independent samples. G: inhibitor of DNA binding 2 (ID2), glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1), and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) mRNA expression levels were measured by quantitative PCR in P7 and P30 murine aortic valves, normalized to β2-microglobulin (B2M), and compared with P1 aortic valves (set as 1, dotted line, n = 6 per time point). Data are reported as means ± SE. Scale bar = 100 μm. *P < 0.05 vs. P1 and #P < 0.05 vs. P7, as determined by one-way ANOVA.

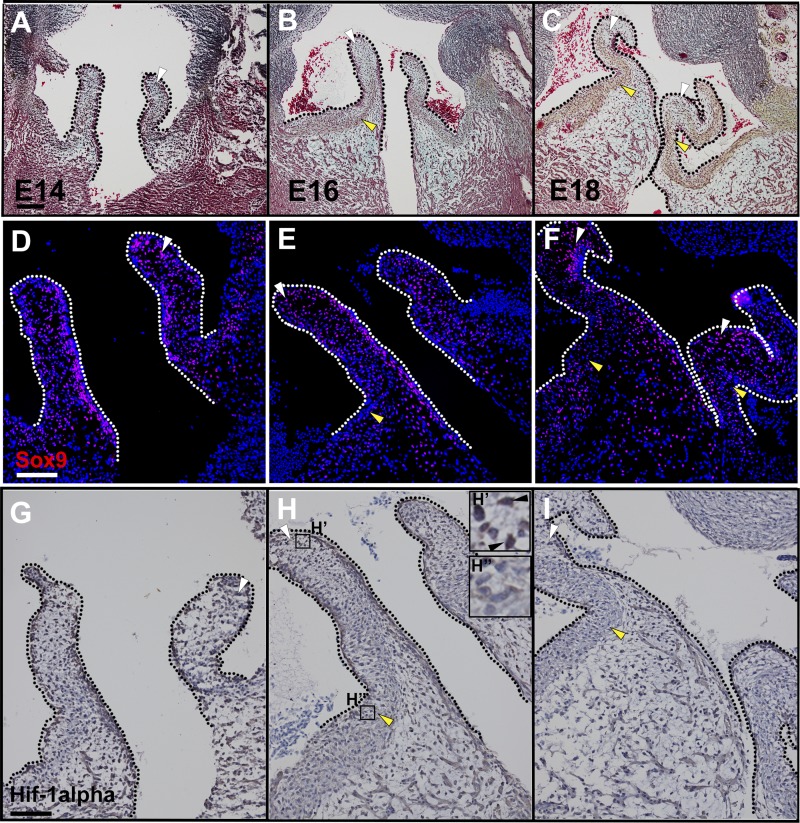

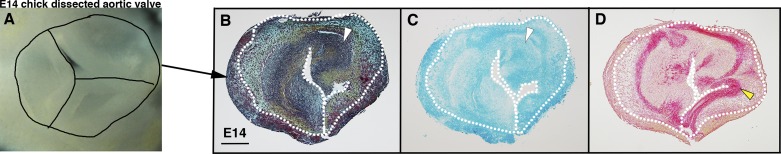

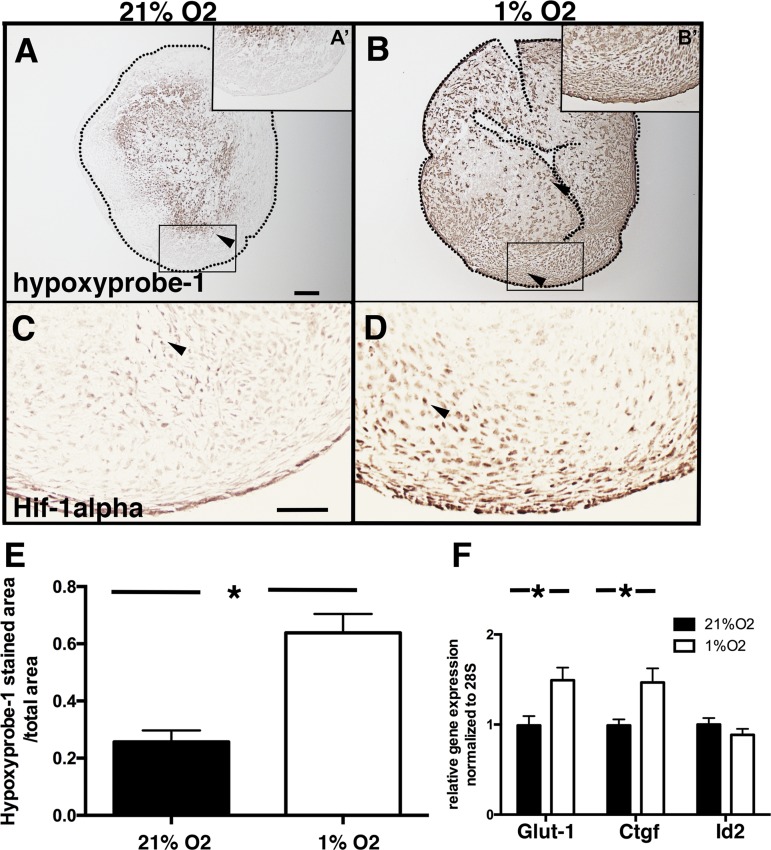

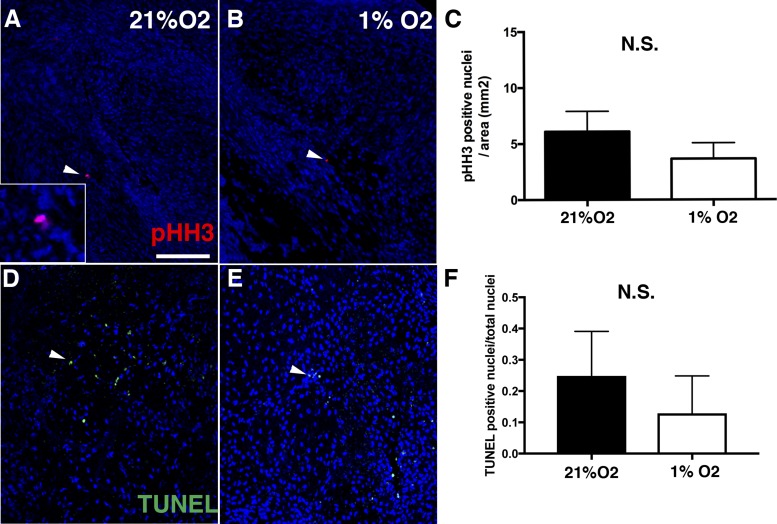

Hypoxia does not affect cell proliferation or collagen expression in cAVOCs.

Heart valve remodeling and tissue hypoxia were examined in chicken embryos at days 14–18 of incubation. Maturation of ECM layers (Fig. 3, A–C) and Sox9 localization in GAG-rich regions of the valves (Fig. 3, D–F) were detected, as previously reported (17, 18). Similar to mouse heart valves, HIF-1α expression was detected in endothelial cells in chicken embryos before hatching. Interestingly, HIF-1α expression was also noted in GAG-rich regions of the maturing valves (Fig. 3, G and H, white arrowheads). The ability of hypoxia to affect VIC proliferation and ECM organization was examined in cAVOCs maintained at different O2 levels. In contrast to two-dimensional cultures, three-dimensional cAVOCs maintained cell-cell contacts and ECM stratification for examination of mechanisms of ECM expression and organization (Fig. 4, A–D) (6). Aortic valve leaflets and adjacent annulus (Fig. 4A) were isolated from E14 chicken embryos that correspond to neonatal mouse embryonic valves (13, 18). For determination of the effects of hypoxia on valve ECM remodeling and organization, E14 cAVOCs were cultured in 1% O2 (hypoxia) compared with normal atmospheric levels of 21% O2 (normoxia). Thus, the direct effects of different O2 concentrations on VIC proliferation, ECM regulation, and stratification were examined.

Fig. 3.

Maturation of the aortic valve extracellular matrix and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) expression in avian embryos before hatching. A–C: representative Movat’s pentachrome staining for embryonic day 14 (E14), E16, and E18 chick heart sections. Glycosaminoglycans are stained in blue (white arrowheads) and fibrillar collagen is stained in yellow (yellow arrowheads). D–F: representative Sox9 staining (white arrowheads) of E14, E16, and E18 chick heart valves. G–I: representative HIF-1α staining (white arrowheads) of E14, E16, and E18 chick heart valves compared with HIF-1α negative nuclei (yellow arrowheads). H′ and H″ insets: higher magnification of HIF-1α-positive and -negative staining, respectively. Scale bar = 100 μm. Dotted lines indicate valve leaflet boundaries.

Fig. 4.

Chicken embryo aortic valve organ cultures (cAVOCs) maintain extracellular matrix localization in vitro. A: representative image of an aortic valve isolated from an embryonic day 14 (E14) chick heart before culture. Individual valve leaflets and annulus are demarcated by black lines. B: representative Movat’s pentachrome staining of E14 cAVOCs cultured for 4 days in medium 199 with 10% FBS. Representative images (from n = 7) are shown for alcian blue staining for glycosaminoglycans (white arrowheads in C) and sirius red staining of collagen (yellow arrowheads in D) performed on E14 cAVOCs cultured for 4 days in medium 199 with 10% FBS. White dotted lines delimit aortic valve leaflets.

Aortic valves were isolated from E14 chicken embryos and cultured at 1% or 21% O2 for 4 days. Tissue hypoxia was measured by HP-1 detection (Fig. 5, A and B) and HIF-1α antibody reactivity (Fig. 5, C and D). For cAVOCs cultured in 21% O2, only the center of the tissue was hypoxic (Fig. 5A). In contrast, 60% of cAVOCs by area, including on the surface of the tissue, were hypoxic, as indicated by HP-1, when cAVOCs were cultured in 1% O2 for 4 days (Fig. 5, B and E). In addition, expression of hypoxia-induced genes Glut1 and Ctgf, but not Id2, was also increased (Fig. 3F), as determined by quantitative PCR. Potential effects on VIC proliferation were determined by pHH3 staining of cAVOCs cultured at 1% or 21% O2. No significant difference in pHH3-positive cells was observed between cAVOCs cultured in normoxic or hypoxic conditions (Fig. 6, A–C). In addition, no significant increase in cell death, as indicated by TUNEL staining, was detected in hypoxic versus normoxic cAVOCs (Fig. 6, D–F). Thus, hypoxia does not affect cell proliferation or induce cell death in cAVOCs cultured for 4 days.

Fig. 5.

Hypoxic indicators are induced in chicken embryo aortic valve organ cultures (cAVOCs) exposed to 1% O2 for 4 days. A and B: representative hypoxyprobe-1 staining (n = 7) for embryonic day 14 (E14) cAVOCs cultured at 21% or 1% O2 and incubated with 200 μM hypoxyprobe-1. A′ and B′: higher magnification of boxed areas. Dotted lines delimit valve leaflets. C and D: representative hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α; arrowheads) immunostaining performed on E14 cAVOCs maintained in 21% or 1% O2. C and D: images correspond to the boxed areas in A and B for stainings of proximal sections. E: the hypoxyprobe-1-stained area/total area was quantified (n = 7 per condition). F: glucose transporter 1 (Glut-1), connective tissue growth factor (Ctgf), and inhibitor of DNA binding 2 (Id2) mRNA expression levels were measured by quantitative PCR in 1% O2 and compared with 21% O2 cultured cAVOCs set as 1 (n = 10 per condition). Data are reported as means ± SE. Scale bar = 100 μm. *P < 0.05 determined by an unpaired t-test.

Fig. 6.

Hypoxia does not induce proliferation or cell death in embryonic day 14 (E14) chicken embryo aortic valve organ cultures (cAVOCs). A and B: representative phosphohistone H3 (pHH3) immunostaining (red nuclei, indicated by arrowheads) of cAVOCs maintained at 21% or 1% O2 for 4 days. C: the number of pHH3-positive nuclei per cAVOC area was quantified (n = 10 per condition). D and E: representative TUNEL staining (green nuclei, arrowheads) was performed on cAVOCs maintained at 21% or 1% O2 for 4 days. F: the number of TUNEL-positive nuclei/total nuclei per cAVOC section was calculated (n = 7 per condition). Data are reported as means ± SE. Scale bar = 100 μm. N.S., not significant as determined by an unpaired t-test.

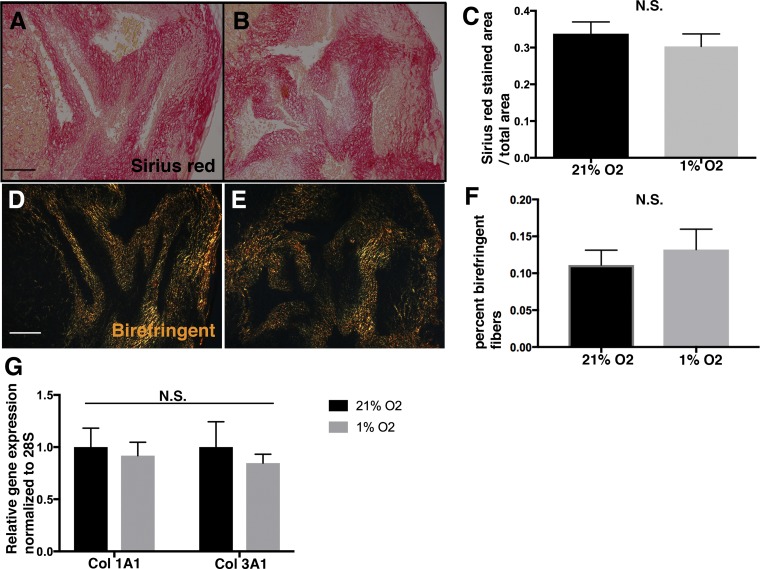

The potential effects of hypoxia on fibrillar collagen expression and localization were examined. Collagen remodeling was examined using picrosirius red staining. No differences in the area of birefringence under polarized light indicative of primitive collagen fibers were observed between the 1% and 21% O2 groups (Fig. 7, A–F). Likewise, no differences in Col1a1 or Col3a1 mRNA expression levels were observed at 1% or 21% O2 (Fig. 7G). Thus, hypoxia does not affect collagen remodeling or gene expression in cultured cAVOCs.

Fig. 7.

Hypoxia does not modulate collagen expression or remodeling in chicken embryo aortic valve organ cultures (cAVOCs). A and B: representative sirius red staining performed on cAVOCs cultured at 21% and 1% O2 for 4 days. C: the sirius red-stained area/total area was quantified (n = 7 per condition). D and E: representative sirius red staining visualized under polarized light of cAVOCs cultured at 21% and 1% O2 for 4 days. F: birefringence of fibers was calculated as the ratio of orange-red to yellow-green detected under polarized light. G: collagen type 1a1 (Col1a1) and collagen type 3a1 (Col3a1) mRNA expression levels were determined by quantitative PCR of cAVOCs maintained in 1% O2 and compared with 21% O2 set to 1.0. Data are reported as means ± SE. Scale bar = 100 μm. N.S., not significant as determined by an unpaired t-test.

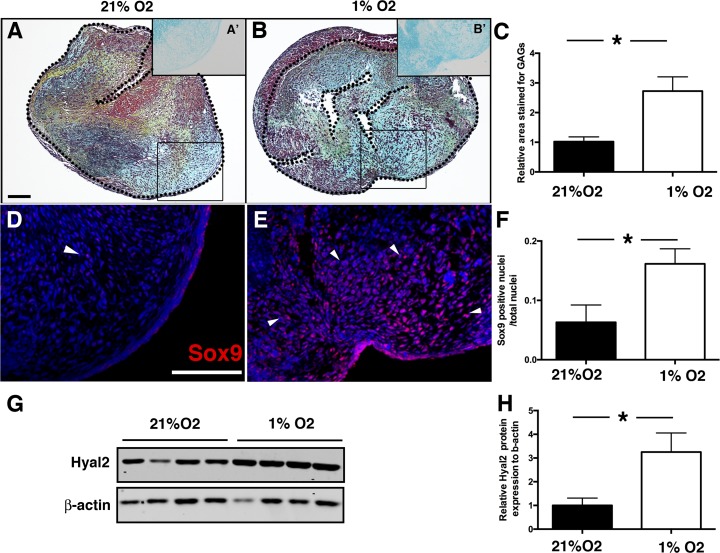

Hypoxia induces Sox9 and GAGs in cAVOCs.

In cartilage, hypoxia (1% O2) promotes Sox9 activity and HA remodeling (3). The ability of hypoxia to similarly affect Sox9 expression, GAG composition, and HA remodeling in developing valves was examined in cAVOCs maintained at 1% or 21% O2. In contrast to collagens, GAG expression, as indicated by alcian blue staining, was increased in hypoxic cAVOCs maintained in 1% O2 relative to normoxia (Fig. 8, A and B). Quantification demonstrated an approximately threefold induction of GAG content when cAVOCs were cultured under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 8C). Immunostaining for Sox9 protein demonstrated that Sox9 nuclear expression was induced in hypoxic cAVOCs (Fig. 8, D–F). Similarly, expression of Hyal2 protein associated with GAG remodeling was significantly increased in hypoxic cAVOCs (Fig. 8, G and H). Thus, hypoxia promotes Sox9 nuclear localization and GAG expression, whereas cell proliferation and collagen expression are relatively unaffected. These data support a role for hypoxia in maintaining a GAG-rich ECM in immature valve leaflets.

Fig. 8.

Hypoxia increases glycosaminoglycan (GAG), Sox9 nuclear localization, and hyaluronidase 2 (Hyal2) expression in chicken embryo aortic valve organ cultures (cAVOCs). A and B: representative Movat’s pentachrome staining performed on cAVOCs cultured at 21% and 1% O2 for 4 days. GAGs are stained in blue, collagen in yellow, and elastin in black. A′ and B′: representative alcian blue staining in regions corresponding to the boxed areas was used for the quantification of GAGs expressed in cAVOCs cultured at 21% and 1% O2 for 4 days. C: the alcian blue (GAG)-stained area/total area was quantified in 1% O2 relative to 21% O2 cultured cAVOCs set to 1 (n = 15 per condition). D and E: representative Sox9 immunostaining of cAVOCs cultured at 21% and 1% O2 for 4 days. F: the number of Sox9-positive nuclei/total nuclei was quantified (n = 7 per condition). G: Hyal2 protein expression was determined compared with β-actin by Western blot analysis (n = 3 per condition). H: Hyal2 protein expression normalized to β–actin was quantified in cAVOCs maintained in 1% O2 relative to 21% O2 set to 1. Scale bar = 100 μm. Data are reported as means ± SE. *P < 0.05 determined by an unpaired t-test.

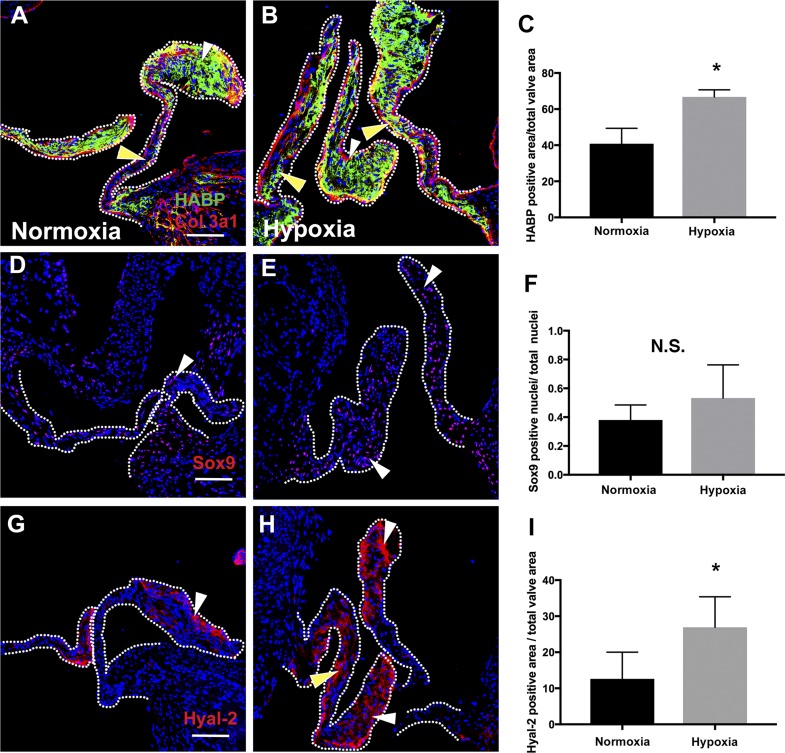

The ability of hypoxia to affect mature valve ECM composition was examined in adult mice exposed to reduced O2. Hypoxia was induced in adult mice exposed to a reduction of inspired O2 [fraction of inspired O2 ()] over the course of 2 wk by 1% per day, from 21% (room air O2) to 7%, and then maintained at 7% O2 for an additional 2 wk, as previously described (22). Examination of aortic valves from these mice demonstrated increased expression of HABP (Fig. 9, A–C) and Hyal2 (Fig. 9, G–I) expression but not a significant increase in Sox9 nuclear localization (Fig. 9, D–F) relative to controls maintained at normoxia. Thus, decreased O2 leads to an increased GAG-rich ECM in adult mice exposed to hypoxia, as was also observed in immature avian aortic valves.

Fig. 9.

Chronic hypoxia induces proteoglycan and hyaluronidase 2 (Hyal2) accumulation in adult mouse heart valves. A and B: representative staining for hyaluronic acid-binding protein (HABP) for heart valves of mice at normoxia (21%) or exposed to hypoxia with decreasing O2 followed by maintenance at 7% O2 for 2 wk (n = 3 per condition). White arrowheads indicate HABP expression at the valve tip; yellow arrowheads indicate expression in the valve body. C: the positive HABP-stained area/total valve area was quantified (n = 3). D and E: representative Sox9 immunostaining (n = 3) of normoxic mice (21% O2) and hypoxic mice (7% O2) is indicated by white arrowheads. F: Sox9-positive nuclei/total nuclei were quantified (n = 3). G and H: representative Hyal2 staining for normoxic (21% O2) and hypoxic mice (7% O2). White arrowheads indicate Hyal2 expression at the valve tip; yellow arrowheads indicate its expression in the valve body. I: positive Hyal2-stained area/total valve area (n = 3). Data are reported as means ± SE. Scale bar = 100 μm. *P < 0.05 as determined by an unpaired t-test. Col3a1, collagen type 3a1; N.S., not significant.

DISCUSSION

Here, we show that tissue hypoxia decreases in mouse aortic valves in the days after birth, concomitant with ECM remodeling and cell cycle arrest of VICs. Maintenance of late embryonic chicken aortic valves in a hypoxic environment leads to increased Sox9 nuclear localization and indicators of HA remodeling but does not affect collagen fibrillogenesis or cell proliferation. Moreover, increased expression of HABP and Hyal2 was also observed in aortic valves of adult mice maintained under hypoxic conditions. Together, these results support a role for hypoxia in maintaining a primitive GAG-rich matrix in immature heart valves before birth (mouse) or hatching (chick) as well as in adult mouse valves.

During postnatal valvulogenesis, the primitive GAG-rich valve primordia remodel to form stratified valve leaflets composed of collagen, proteoglycan, and elastin-rich ECM layers (14). The primitive valve matrix is predominantly composed of HA and versican, which has been characterized as a provisional matrix that facilitates tissue growth and remodeling (30). After birth, increased collagen fibers of the fibrosa and elastin fibers on the flow side of the valves provide increased structural integrity and elasticity needed for mature valve function (28). Here, we show that exposure to hypoxia in chicken valve cultures promotes the immature HA-rich provisional matrix without affecting expression of collagen matrix maturation or cell cycle inhibition. Thus, it is likely that the tissue hypoxia promotes immature ECM composition, but exposure to atmospheric O2 is not the primary mediator of increased ECM maturation or cell cycle arrest after birth. Additional work is needed to identify the molecular, biomechanical, or hemodynamic mechanisms that promote adult valve leaflet collagen production and VIC cell cycle arrest in the weeks after birth.

Previous studies have provided evidence for conservation with regulatory pathways that control cartilage and bone development in valve maturation and disease (5). Like the immature heart valve matrix, the ECM of developing cartilage is composed primarily of HA and chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans, which are regulated in many cases by the chondrogenic transcription factor Sox9 (20). In embryonic cartilage, Sox9 promotes cartilage cell proliferation and differentiation evident in the GAG-rich ECM (1). Hypoxia has a well-established role in cartilage differentiation and homeostasis of the avascular GAG-rich ECM (21). Interestingly, the transcription factor HIF-1α, which is induced by hypoxia, promotes induction of Sox9 activity in chondrocytes (3). Prenatal tissue hypoxia, as indicated by HP-1 in mice, coincides with cartilage lineage development and also promotes Sox9 activation of chondrogenic gene expression (3). Similarly, hypoxia promotes chondrogenic commitment and differentiation of human embryonic stem cells (32). In developing heart valves, Sox9 similarly promotes early endocardial cushion mesenchyme proliferation and later expression of the cartilage-like matrix (19). Here, we demonstrate that hypoxia promotes Sox9 nuclear localization and GAG expression in immature heart valve tissue, further supporting conservation of chondrogenic regulatory mechanisms in heart valve development.

Myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) is highly prevalent in the United States and is characterized by thickening of valve leaflets with increased GAGs and dysregulated collagen fibers, which can lead to valvular insufficiency, heart failure, and death, if untreated (16). Surgical repair or replacement is the current standard of care for MMVD but often is contraindicated in elderly patients or in the presence of severe cardiac dysfunction (23). Thus, the increased knowledge of the driving forces behind GAG accumulation or remodeling is needed for the successful development of nonsurgical medical therapies. MMVD can be initiated by genetic, inflammatory, or pharmacological factors, and progression of myxomatous degeneration of the valve ECM is poorly understood (16). In MMVD, Sox9 is known to increase along with the accumulation of the GAG matrix, which leads to thickening of the valve leaflet (4, 11). Thus, GAGs are found in abundance in MMVD in addition to indicators of HA remodeling (9). Hypoxia has been implicated as a contributing factor in valve disease progression, as O2 diffusion might not be as efficient as the valve becomes thickened in MMVD. In addition, loss of ECM stratification is observed in adult porcine aortic and mitral valves cultured under hypoxic conditions (27). In the present study, we show that exposure of adult mice to hypoxia leads to increased indicators of HA remodeling, supporting a role for O2 in the maintenance of GAG expression in normal heart valves. In rheumatic mitral valves, HIF-1α expression, indicative of hypoxia, is induced (26), but it is not currently known if tissue hypoxia promotes increased GAGs and HA remodeling in MMVD. Taken together, there is accumulating evidence for conservation of GAG regulation and expression linked to hypoxia in developing valves, MMVD, and cartilage.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant R01-HL-094319 (to K. E. Yutzey), an American Association of Anatomists Postdoctoral Fellowship Award (to A. Hulin), and an American Heart Association Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship Award (to D. Amofa).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.H. and K.E.Y. conceived and designed research; D.A., A.H., and Y.N. performed experiments; D.A., A.H., and K.E.Y. analyzed data; D.A., A.H., Y.N., H.A.S., and K.E.Y. interpreted results of experiments; D.A. and A.H. prepared figures; D.A., A.H., and K.E.Y. drafted manuscript; D.A., A.H., and K.E.Y. edited and revised manuscript; D.A., A.H., Y.N., H.A.S., and K.E.Y. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Biplab Dasgupta laboratory for use of the hypoxystation and Christina Alfieri for technical advice and support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akiyama H, Chaboissier MC, Martin JF, Schedl A, de Crombrugghe B. The transcription factor Sox9 has essential roles in successive steps of the chondrocyte differentiation pathway and is required for expression of Sox5 and Sox6. Genes Dev 16: 2813–2828, 2002. doi: 10.1101/gad.1017802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alfieri CM, Cheek J, Chakraborty S, Yutzey KE. Wnt signaling in heart valve development and osteogenic gene induction. Dev Biol 338: 127–135, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amarilio R, Viukov SV, Sharir A, Eshkar-Oren I, Johnson RS, Zelzer E. HIF1alpha regulation of Sox9 is necessary to maintain differentiation of hypoxic prechondrogenic cells during early skeletogenesis. Development 134: 3917–3928, 2007. doi: 10.1242/dev.008441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caira FC, Stock SR, Gleason TG, McGee EC, Huang J, Bonow RO, Spelsberg TC, McCarthy PM, Rahimtoola SH, Rajamannan NM. Human degenerative valve disease is associated with up-regulation of low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 receptor-mediated bone formation. J Am Coll Cardiol 47: 1707–1712, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Combs MD, Yutzey KE. Heart valve development: regulatory networks in development and disease. Circ Res 105: 408–421, 2009. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.201566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fang M, Alfieri CM, Hulin A, Conway SJ, Yutzey KE. Loss of β-catenin promotes chondrogenic differentiation of aortic valve interstitial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 34: 2601–2608, 2014. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao F, Okunieff P, Han Z, Ding I, Wang L, Liu W, Zhang J, Yang S, Chen J, Underhill CB, Kim S, Zhang L. Hypoxia-induced alterations in hyaluronan and hyaluronidase. Adv Exp Med Biol 566: 249–256, 2005. doi: 10.1007/0-387-26206-7_33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomez-Stallons MV, Wirrig-Schwendeman EE, Hassel KR, Conway SJ, Yutzey KE. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling is required for aortic valve calcification. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 36: 1398–1405, 2016. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.307526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grande-Allen KJ, Calabro A, Gupta V, Wight TN, Hascall VC, Vesely I. Glycosaminoglycans and proteoglycans in normal mitral valve leaflets and chordae: association with regions of tensile and compressive loading. Glycobiology 14: 621–633, 2004. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwh076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta V, Barzilla JE, Mendez JS, Stephens EH, Lee EL, Collard CD, Laucirica R, Weigel PH, Grande-Allen KJ. Abundance and location of proteoglycans and hyaluronan within normal and myxomatous mitral valves. Cardiovasc Pathol 18: 191–197, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta V, Tseng H, Lawrence BD, Grande-Allen KJ. Effect of cyclic mechanical strain on glycosaminoglycan and proteoglycan synthesis by heart valve cells. Acta Biomater 5: 531–540, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashimoto K, Fukuda K, Yamazaki K, Yamamoto N, Matsushita T, Hayakawa S, Munakata H, Hamanishi C. Hypoxia-induced hyaluronan synthesis by articular chondrocytes: the role of nitric oxide. Inflamm Res 55: 72–77, 2006. doi: 10.1007/s00011-005-0012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hinton RB Jr, Lincoln J, Deutsch GH, Osinska H, Manning PB, Benson DW, Yutzey KE. Extracellular matrix remodeling and organization in developing and diseased aortic valves. Circ Res 98: 1431–1438, 2006. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000224114.65109.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinton RB, Yutzey KE. Heart valve structure and function in development and disease. Annu Rev Physiol 73: 29–46, 2011. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hulin A, Moore V, James JM, Yutzey KE. Loss of Axin2 results in impaired heart valve maturation and subsequent myxomatous valve disease. Cardiovasc Res 113: 40–51, 2017. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvw229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levine RA, Hagége AA, Judge DP, Padala M, Dal-Bianco JP, Aikawa E, Beaudoin J, Bischoff J, Bouatia-Naji N, Bruneval P, Butcher JT, Carpentier A, Chaput M, Chester AH, Clusel C, Delling FN, Dietz HC, Dina C, Durst R, Fernandez-Friera L, Handschumacher MD, Jensen MO, Jeunemaitre XP, Le Marec H, Le Tourneau T, Markwald RR, Mérot J, Messas E, Milan DP, Neri T, Norris RA, Peal D, Perrocheau M, Probst V, Pucéat M, Rosenthal N, Solis J, Schott JJ, Schwammenthal E, Slaugenhaupt SA, Song JK, Yacoub MH; Leducq Mitral Transatlantic Network . Mitral valve disease–morphology and mechanisms. Nat Rev Cardiol 12: 689–710, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lincoln J, Alfieri CM, Yutzey KE. BMP and FGF regulatory pathways control cell lineage diversification of heart valve precursor cells. Dev Biol 292: 292–302, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lincoln J, Alfieri CM, Yutzey KE. Development of heart valve leaflets and supporting apparatus in chicken and mouse embryos. Dev Dyn 230: 239–250, 2004. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lincoln J, Kist R, Scherer G, Yutzey KE. Sox9 is required for precursor cell expansion and extracellular matrix gene expression. Dev Biol 302: 376–388, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lincoln J, Lange AW, Yutzey KE. Hearts and bones: shared regulatory mechanisms in heart valve, cartilage, tendon, and bone development. Dev Biol 294: 292–302, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maes C. Signaling pathways effecting crosstalk between cartilage and adjacent tissues: seminars in cell and developmental biology: the biology and pathology of cartilage. Semin Cell Dev Biol 62: 16–33, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakada Y, Canseco DC, Thet S, Abdisalaam S, Asaithamby A, Santos CX, Shah AM, Zhang H, Faber JE, Kinter MT, Szweda LI, Xing C, Hu Z, Deberardinis RJ, Schiattarella G, Hill JA, Oz O, Lu Z, Zhang CC, Kimura W, Sadek HA. Hypoxia induces heart regeneration in adult mice. Nature 541: 222–227, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nature20173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishimura RA, Vahanian A, Eleid MF, Mack MJ. Mitral valve disease–current management and future challenges. Lancet 387: 1324–1334, 2016. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00558-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puente BN, Kimura W, Muralidhar SA, Moon J, Amatruda JF, Phelps KL, Grinsfelder D, Rothermel BA, Chen R, Garcia JA, Santos CX, Thet S, Mori E, Kinter MT, Rindler PM, Zacchigna S, Mukherjee S, Chen DJ, Mahmoud AI, Giacca M, Rabinovitch PS, Aroumougame A, Shah AM, Szweda LI, Sadek HA. The oxygen-rich postnatal environment induces cardiomyocyte cell-cycle arrest through DNA damage response. Cell 157: 565–579, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robins JC, Akeno N, Mukherjee A, Dalal RR, Aronow BJ, Koopman P, Clemens TL. Hypoxia induces chondrocyte-specific gene expression in mesenchymal cells in association with transcriptional activation of Sox9. Bone 37: 313–322, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salhiyyah K, Sarathchandra P, Latif N, Yacoub MH, Chester AH. Hypoxia-mediated regulation of the secretory properties of mitral valve interstitial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 313: H14–H23, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00720.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sapp MC, Krishnamurthy VK, Puperi DS, Bhatnagar S, Fatora G, Mutyala N, Grande-Allen KJ. Differential cell-matrix responses in hypoxia-stimulated aortic versus mitral valves. J R Soc Interface 13: 13, 2016. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2016.0449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schoen FJ. Evolving concepts of cardiac valve dynamics: the continuum of development, functional structure, pathobiology, and tissue engineering. Circulation 118: 1864–1880, 2008. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.805911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimizu I, Aprahamian T, Kikuchi R, Shimizu A, Papanicolaou KN, MacLauchlan S, Maruyama S, Walsh K. Vascular rarefaction mediates whitening of brown fat in obesity. J Clin Invest 124: 2099–2112, 2014. doi: 10.1172/JCI71643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wight TN. Provisional matrix: a role for versican and hyaluronan. Matrix Biol 60–61: 38–56, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wikenheiser J, Doughman YQ, Fisher SA, Watanabe M. Differential levels of tissue hypoxia in the developing chicken heart. Dev Dyn 235: 115–123, 2006. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yodmuang S, Marolt D, Marcos-Campos I, Gadjanski I, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Synergistic effects of hypoxia and morphogenetic factors on early chondrogenic commitment of human embryonic stem cells in embryoid body culture. Stem Cell Rev 11: 228–241, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s12015-015-9584-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yutzey KE. Cardiovascular biology: switched at birth. Nature 509: 572–573, 2014. doi: 10.1038/509572a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang G, Ezura Y, Chervoneva I, Robinson PS, Beason DP, Carine ET, Soslowsky LJ, Iozzo RV, Birk DE. Decorin regulates assembly of collagen fibrils and acquisition of biomechanical properties during tendon development. J Cell Biochem 98: 1436–1449, 2006. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]