Neutrophils are abundant in abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), and myeloperoxidase (MPO), prominently expressed in neutrophils, is associated with AAA in humans. This study demonstrates that MPO gene deletion or supplementation with the natural product taurine, which can scavenge MPO-generated oxidants, can prevent AAA formation, suggesting an attractive potential therapeutic strategy for AAA.

Keywords: abdominal aortic aneurysm, myeloperoxidase, taurine, angiotensin II, elastase, calcium chloride

Abstract

Oxidative stress plays a fundamental role in abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) formation. Activated polymorphonuclear leukocytes (or neutrophils) are associated with AAA and express myeloperoxidase (MPO), which promotes inflammation, matrix degradation, and other pathological features of AAA, including enhanced oxidative stress through generation of reactive oxygen species. Both plasma and aortic MPO levels are elevated in patients with AAA, but the role of MPO in AAA pathogenesis has, heretofore, never been investigated. Here, we show that MPO gene deletion attenuates AAA formation in two animal models: ANG II infusion in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice and elastase perfusion in C57BL/6 mice. Oral administration of taurine [1% or 4% (wt/vol) in drinking water], an amino acid known to react rapidly with MPO-generated oxidants like hypochlorous acid, also prevented AAA formation in the ANG II and elastase models as well as the CaCl2 application model of AAA formation while reducing aortic peroxidase activity and aortic protein-bound dityrosine levels, an oxidative cross link formed by MPO. Both MPO gene deletion and taurine supplementation blunted aortic macrophage accumulation, elastin fragmentation, and matrix metalloproteinase activation, key features of AAA pathogenesis. Moreover, MPO gene deletion and taurine administration significantly attenuated the induction of serum amyloid A, which promotes ANG II-induced AAAs. These data implicate MPO in AAA pathogenesis and suggest that studies exploring whether taurine can serve as a potential therapeutic for the prevention or treatment of AAA in patients merit consideration.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Neutrophils are abundant in abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), and myeloperoxidase (MPO), prominently expressed in neutrophils, is associated with AAA in humans. This study demonstrates that MPO gene deletion or supplementation with the natural product taurine, which can scavenge MPO-generated oxidants, can prevent AAA formation, suggesting an attractive potential therapeutic strategy for AAA.

INTRODUCTION

Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) are a common and life-threatening condition that occurs in up to 9% of elderly individuals >65 yr of age (37). This complex vascular disorder involves loss of smooth muscle cells and damage of structural connective tissue leading to progressive aortic dilation and/or catastrophic rupture and death (18). Surgical and percutaneous repair is associated with significant operative risks and complications (3), and, currently, there is no effective medical treatment for AAA.

Oxidative stress plays an important role in AAA pathogenesis (23, 24). Polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs or neutrophils) are key mediators of oxidative stress and are present abundantly in human AAA tissues and elastase-induced AAA, where they play a crucial role in recruiting inflammatory cells to the aorta (12). Activated PMNs release myeloperoxidase (MPO), an enzyme that produces hypochlorous acid (HOCl) from H2O2 and Cl−; HOCl reacts with a variety of biomolecules, including proteins, the double bonds of cholesterol and fatty acid groups, and nucleic acids, thereby causing oxidative damage (17). MPO-derived HOCl inactivates tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 and α1-antiprotease, which may indirectly stimulate proteolytic activity and matrix degradation (4, 41). Moreover, MPO can use H2O2 to convert l-tyrosine to tyrosyl radical and dityrosine (diTyr), an indicator of posttranslational oxidative cross link of proteins (11, 15). MPO can also use nitric oxide to promote protein nitration and lipid peroxidation, consistent with a complex and multifaceted role in promoting oxidative stress (10). Together, these studies suggest that MPO-mediated oxidative stress may play an important role in the pathogenesis of AAA.

Serum amyloid A (SAA) is an inducible acute-phase reactant produced by the liver, inflammatory cells, and adipocytes, whose induction has been linked to oxidative stress produced by lipid peroxidation products in mice fed an atherogenic diet (20). Cytokines produced during chronic inflammation also induce SAA, which, in turn, upregulates chemokine expression and activates matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), key mediators of AAA. SAA expression has been recently reported to be upregulated in ANG II-induced AAA, and genetic deletion of SAA prevented ANG II-induced AAA formation (42), suggesting that SAA upregulation contributes to AAA pathogenesis. However, whether MPO regulates SAA in the context of AAA formation is unknown.

Taurine, a naturally occurring amino acid, has been studied in conditions associated with enhanced oxidative stress, including smoking, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, neuronal injury, diabetes, cyclosporine-induced hepatotoxicity, ischemia-reperfusion injury, and diabetes in humans (6, 8, 14, 16, 27, 33). By reacting with HOCl to form taurine-chloramine, taurine can attenuate HOCl-mediated oxidation and tissue damage, reducing inflammation. Taurine also possesses other potential antioxidant effects, including suppression of reactive oxygen species generation and favorably modulating antioxidant enzyme levels (35).

In this study, we investigated the role of MPO in AAA formation and the preventive effects of taurine using three murine models of AAA: 1) ANG II infusion into hyperlipidemic apolipoprotein E knockout (ApoE−/−) mice, 2) elastase perfusion, and 3) CaCl2 application in C57BL/6 mice. We also examined the impact of MPO deficiency on AAA formation using MPO knockout (MPO−/−) mice. Our results suggest that MPO plays an important role in AAA pathogenesis and that taurine supplementation is effective at mitigating AAA formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

C57BL/6, ApoE−/−, and MPO−/− mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). MPO−/− mice were bred with ApoE−/− mice to obtain heterozygotes in the ApoE−/− background, which were interbred to produce littermates that were wild-type (WT), heterozygous (+/−), or homozygous (−/−) for MPO. The animal experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of Iowa, University of Cincinnati, and Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University.

ANG II-induced AAA model.

Six-month-old male ApoE−/−, ApoE−/−MPO+/−, and ApoE−/−MPO−/− mice received saline (placebo control) or ANG II (1,000 ng·kg−1·min−1, A9525, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) infused via osmotic mini-pumps (model 2004, Alzet, Cupertino, CA) inserted into the subcutaneous space in the interscapular area under parenteral anesthesia, as previously described (7). In separate experiments, ApoE−/− mice received saline or infusion of ANG II in the presence or absence of oral taurine [1% and 4% (wt/vol)]. These taurine concentrations were chosen on the basis of good tolerability and efficacy at reducing oxidative stress in mice and rats (8, 25). Mice were placed on plain or taurine-supplemented drinking water for 5 days before mini-pump implantation and continued for the study duration of 28 days. Aneurysms of the suprarenal aorta occur in ~80% of ANG II-infused mice at this dose and time period. Blood pressure measurements were obtained using a previously validated tail-cuff method (Coda 6, Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT). Mice were conditioned to the instrument and procedure for 5 consecutive days before pump implantation. To ensure a more robust estimation of systolic blood pressure (SBP), we used the interquartile mean of SBP measurements achieved through 30 measurement cycles every other day. Unless otherwise specified, mice were euthanized 4 wk after pump implantation for the assessment of aneurysm formation and other parameters, as described below.

Elastase-induced AAA model.

Male C57BL/6 mice at ∼3 mo of age were randomly assigned to receive water without or with taurine supplementation [1% or 4% (wt/vol)] for 5 days before elastase induction of AAA. Under parenteral anesthesia with pentobarbital, a laparotomy was performed, and the infrarenal abdominal aorta from beneath the left renal vein to the iliac bifurcation was isolated. The isolated segment was tied off, exsanguinated, and then perfused with porcine pancreatic elastase (PPE) type I (E-1250, Sigma) for 5 min. Heat-inactivated elastase was perfused in control mice. In separate experiments, elastase was perfused in WT and MPO−/− mice. Unless otherwise specified, mice were euthanized 14 days after elastase perfusion for the assessment of aneurysm formation and other parameters, as described below. This protocol was adapted with permission from Thompson et al. (37).

CaCl2-induced AAA model.

Twelve-week-old male C57BL/6 mice received water without or with taurine supplementation [1% (wt/vol)] for 5 days before CaCl2 induction of AAA. Mice were anesthetized, and a laparotomy was performed as described above, after which saline (sham control) or 0.5 mol/l of CaCl2 (Sigma-Aldrich) was applied to the infrarenal aortic adventitial surface for 15 min followed by a rinse with 0.9% sterile saline and surgical closure. After 21 days, animals were anesthetized, aortic outer diameter was measured, and aortic tissues were removed for further experiments, as described above.

Aortic tissue collection and measurement.

Aortic tissue samples were harvested at several time points over the aneurysm induction period (3 and 14 days in the elastase and CaCl2 models and 4, 7, and 28 days in the ANG II model). The chest and abdominal cavities were opened, and blood was drawn from the right ventricle at the time of euthanasia. Aortas were irrigated with cold PBS through the left ventricle. Using a dissection microscope, we collected aortic roots for atherosclerosis quantification, exposed the abdominal aorta, and dissected the periadventitial tissue carefully from the wall of the aorta. Aortic measurements were determined with a stage micrometer and optical eyepiece reticle. For the elastase model, the percent increase in outer diameter was calculated from the difference between the preintervention and final measurements. An AAA was defined as an increase in the baseline outer diameter of 50%. The abdominal aorta, from the last intercostal artery to the ileal bifurcation, was sectioned and weighed, and the aneurysmal areas were fixed in paraformaldehyde [4% (wt/vol)] for immunohistochemistry or homogenized/sonicated for biochemical assays. Representative images of aortic histology were taken at the midpoint of the suprarenal aorta (ANG II model) or infrarenal aorta (elastase model) to maintain consistency. Aortic root sections were analyzed for atherosclerosis, as previously reported (7, 36). Blood samples were assayed for lipid profiles, as previously reported (36).

Gelatin zymography for detection of MMP-2 and MMP-9.

Protein was extracted from excised abdominal aortas that had been snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized in a buffer containing 1 M NaCl, 2 M urea, 0.2 mM PMSF, 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 0.1% EDTA, 0.1% Brij-35, and a 1:100 dilution of protease inhibitor cocktail (P8340, Sigma). Samples were sonicated on ice and centrifuged, and supernatants were used to quantify protein content (Pierce BCA system, Pierce, Rockford, IL). Protein lysate (600 µg) was placed in a nonreducing zymogram buffer (no. 161-0764, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and applied without boiling to a 10% zymogram gel (no. 161-1167, Bio-Rad). Gels were incubated in 2% Triton X-100 at room temperature for 30 min and then rinsed in H2O for 5 min. Gels were incubated overnight at 37°C with gentle agitation in buffer containing 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.5), 0.15 mM NaCl, 5 mM anhydrous d-glucose, 5 μM ZnCl2, and 30% Brij-35. Proteins were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 solution (Bio-Rad) and destained with a solution containing 40% methanol, 10% acetic acid, and 50% H2O.

Peroxidase activity assay.

Abdominal aortic tissues were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer containing 0.5% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide. Homogenates were then freeze-thawed twice and sonicated on ice. Suspensions were centrifuged at 40,000 g for 15 min, and supernatants were harvested and separated using Sephadex G-75 columns. Assays were performed using o-dianisidine-based peroxidase activity measurements, as previously described (43). Briefly, 0.1 ml of samples was mixed with 2.9 ml of 50 mM phosphate buffer containing 0.53 mM o-dianisidine and 0.15 mM H2O2. Absorbance changes at 460 nm were measured in a spectrometer every 15 s for 10 min. Peroxidase activity was calculated from a standard curve prepared using purified human neutrophil-derived MPO. For the elastase and CaCl2 models, we used a commercial detection kit (Fluoro MPO kit, Cell Technology), as previously reported (26), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunohistochemistry.

Paraformaldehyde-fixed [4% (wt/vol)] aortic sections were transferred to ethanol before being embedded in paraffin. Cross sections (5 µm) were mounted and stained with hematoxylin-and-eosin (H&E) or Verhoeff van Gieson stain for elastin. Antibodies for MPO (ab45977, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), Mac-3 (553322, BD PharMingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ), and SAA (AF2948, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) were used in conjunction with the HistoMouse-SP kit (95-9541, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or DAB substrate kit (SK-4100, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA).

Tyrosine modification analysis by LC/MS/MS.

Stable isotope dilution LC/MS/MS analyses were performed to quantify the oxidized amino acids in abdominal aortic tissues, as previously reported (1). Briefly, samples were delipidated, isotope-labeled internal standards were added, and samples were then hydrolyzed in methane sulfonic acid under inert atmosphere. Hydrolysates were resolved on an ultra-high-performance, reverse-phase column and introduced into a Shimadzu 8050 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer using a discontinuous gradient. Oxidized amino acids and their precursors were monitored with characteristic parent-daughter ion transitions, as previously described (1).

Western blot analysis.

Protein extraction and Western blot analysis were performed as previously described (7). The antibodies used were SAA (AF2948, R&D Systems), transferrin (ab82411, Abcam), MPO (ab9535, Abcam), and GAPDH (Ambion).

Statistical analysis.

Results are expressed as means ± SE unless otherwise noted. Differences between two groups were analyzed by Student’s t-test, and differences between multiple groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by least significant difference testing for multiple comparisons. Only those mice with elastase-induced aneurysms from the same enzyme lot were compared. A Fisher exact test was used to analyze categorical data. P values of <0.05 were considered to be significant.

RESULTS

MPO deficiency protected against AAA formation induced by ANG II in ApoE-deficient mice.

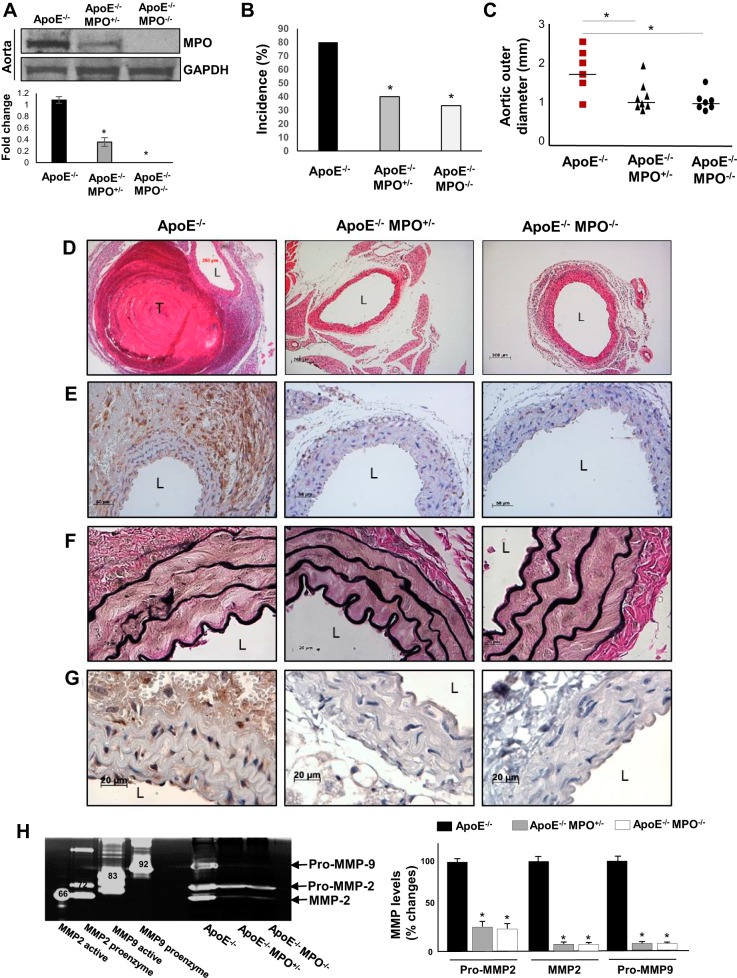

To test the hypothesis that MPO contributes to AAA formation, we infused ANG II into MPO/ApoE compound-deficient mice. Reduced MPO protein expression level in these mice was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, deletion of one (MPO+/−) or both (MPO−/−) alleles markedly protected against ANG II-induced AAA formation, as evidenced by reduced aneurysm incidence and maximal aortic diameter (Fig. 1, B and C). Histological analyses demonstrated that thrombus formation, macrophage accumulation, and elastase degradation during AAA formation were reduced significantly in MPO/ApoE-deficient mice (Fig. 1, E–F). MMP-2 and MMP-9 levels were also significantly diminished in MPO-deficient mice (Fig. 1H). Importantly, diffuse immunostaining for MPO was detected in aortic tissues of ApoE-deficient mice, particularly in the adventitia, which was abrogated in MPO/ApoE-deficient mice (Fig. 1G).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of ANG II-induced abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) in apolipoprotein E (ApoE)-deficient (ApoE−/−) mice versus ApoE/myeloperoxidase (MPO) double-knockout mice. A: MPO protein expression levels in ApoE−/−, ApoE−/−MPO+/−, and ApoE−/−MPO−/− mice, as examined by Western blot analysis. *P < 0.01 vs. wild-type (WT) mice (n = 3). B and C: AAA incidence (B) and mean aortic outer diameter (C) in ApoE−/−, ApoE−/−MPO+/−, and ApoE−/−MPO−/− mice infused with ANG II. *P < 0.05 vs. ApoE−/− control mice (n = 10). Representative histology demonstrated thrombus formation (D; hematoxylin and eosin staining), macrophage accumulation (E; Mac-3 staining), elastin fragmentation (F: Verhoeff van Gieson staining), and MPO immunostaining (G). L, lumen; T, intramural thrombus. H: representative zymogram (left) demonstrating aortic pro-matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, MMP-2, and pro-MMP-9 levels and quantified data (right). Positive controls are shown in the left four lanes of the zymogram; bands denote molecular weights of the respective enzymes. *P < 0.05 vs. ApoE−/− control (n = 3).

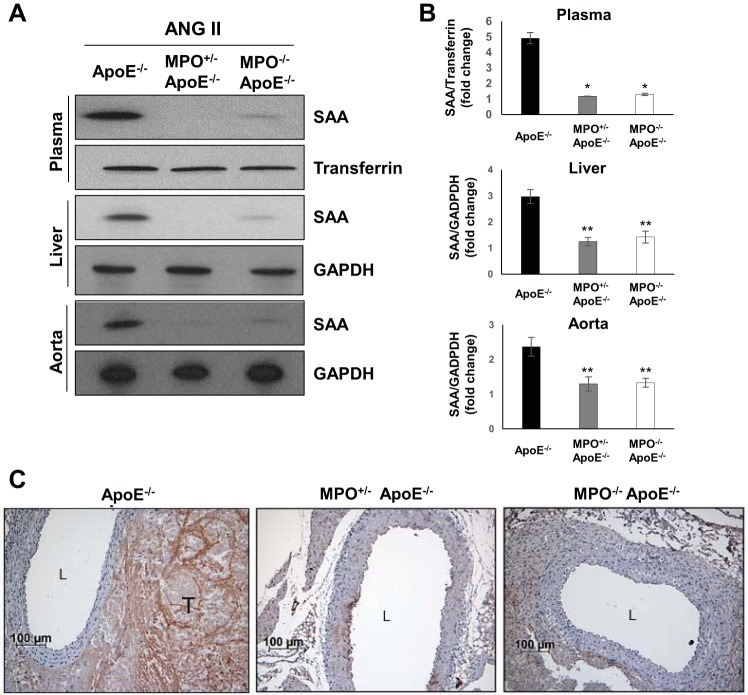

MPO deficiency reduced SAA expression during AAA formation.

SAA expression in the plasma, liver, and aorta during AAA formation was markedly reduced in MPO/ApoE-deficient mice compared with ApoE−/− mice (Fig. 2, A and B). Reduced SAA accumulation in aortic tissues from MPO/ApoE-deficient mice was also confirmed by immunostaining (Fig. 2C). In contrast, MPO gene deletion did not affect blood pressure in response to ANG II infusion (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Serum amyloid A (SAA) expression levels in apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE−/−) mice versus ApoE/myeloperoxidase (MPO) double-knockout mice infused with ANG II. A: representative Western blot showing SAA protein expression in the plasma, liver, and aorta in ApoE−/−, ApoE−/−/MPO+/−, and ApoE−/−/MPO−/− mice infused with ANG II. Transferrin and GAPDH are shown as loading controls. B: densitometric analysis of SAA protein expression. *P < 0.01 and **P < 0.05 vs. wild-type control mice (n = 3). C: representative images of aortic SAA immunostaining in ApoE−/−, ApoE−/−/MPO+/−, and ApoE−/−/MPO−/− mice infused with ANG II. L, lumen; T, intramural thrombus.

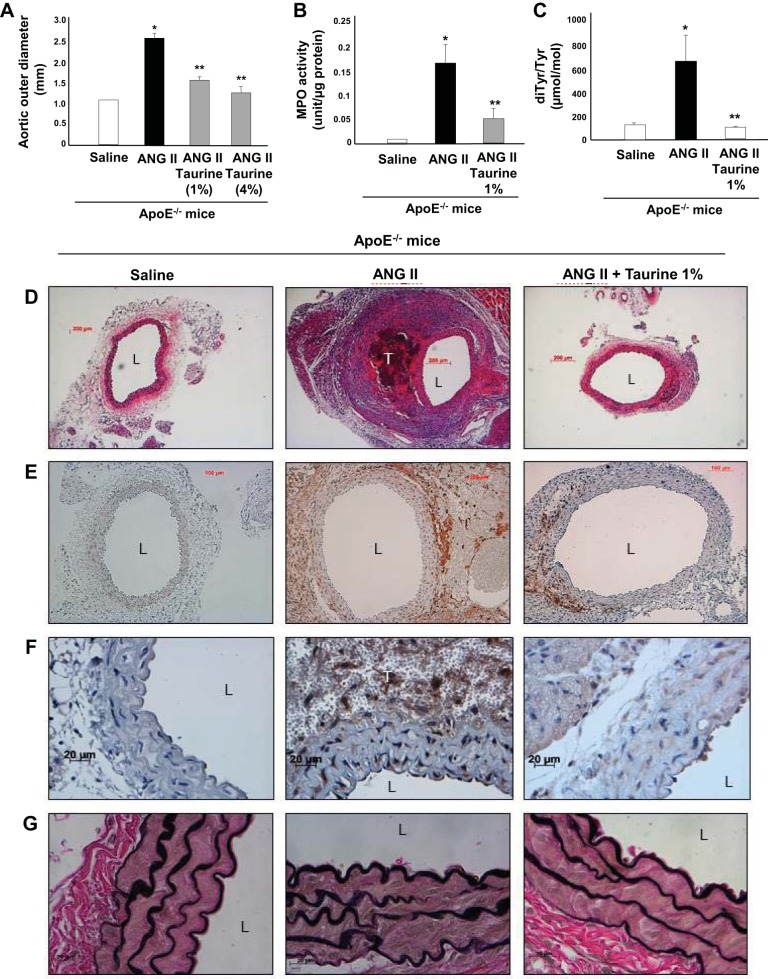

Supplemental taurine attenuated ANG II-induced AAA formation.

We next supplemented the drinking water of ApoE−/− mice with taurine [1% or 4% (wt/vol)], both of which significantly reduced ANG II-induced AAA formation, as assessed by maximal aortic diameter (Fig. 3A) and weight (data not shown) measured at death. Because both 4% and 1% taurine supplementation produced qualitatively similar results, in subsequent experiments, we used 1% taurine to limit potentially nonspecific effects associated with higher doses. To test the impact of taurine on peroxidase activity, we adopted a biochemical assay designed to exclude myoglobin and hemoglobin contaminants that could be associated with tissue thrombus (43). Using this assay, we detected a significant increase in aortic peroxidase activity induced during ANG II infusion that was strongly blocked by taurine administration (Fig. 3B). To quantify the effects of taurine on one aspect of oxidative stress noted to be produced by MPO, we analyzed aortic protein-bound diTyr levels, a posttranslational oxidative cross link of proteins generated by MPO and other tyrosyl radical-generating pathways (15, 19), using LC/MS/MS. We detected a significant increase in diTyr levels in aortas from ANG II-infused mice, which was markedly reduced by taurine treatment (Fig. 3C). Histological analyses demonstrated extensive intramural thrombus formation (H&E; Fig. 3D), macrophage accumulation (Mac-3; Fig. 3E), and localized MPO accumulation (MPO; Fig. 3F) in aortas of ANG II-infused mice, all of which were attenuated markedly by taurine. Taurine administration also resulted in a dose-dependent diminution in an AAA pathology score (data not shown), as defined by Manning et al. (22). Mortality from AAA dissection/rupture was 20% in control mice and 0% in taurine-administered mice (data not shown). Although taurine supplementation conferred protection against AAA, it did not reduce known parameters associated with aneurysmal growth rate, such as SBP, aortic root atherosclerosis, or lipid levels (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Effects of taurine supplementation on ANG II-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm formation in apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE−/−) mice. A−C: effects of taurine [1% or 4% (wt/vol) in drinking water] on mean outer aortic diameter (A), myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity (B), and dityrosine (diTyr) levels (C). *P < 0.05 vs. saline control; **P < 0.05 vs. ANG II (n = 12). D−G: representative histology demonstrating thrombus formation (D; hematoxylin and eosin staining), macrophage infiltration (E; Mac-3 staining), MPO accumulation (F), and elastin degradation (G; Verhoeff van Gieson staining). L, lumen; T, intramural thrombus.

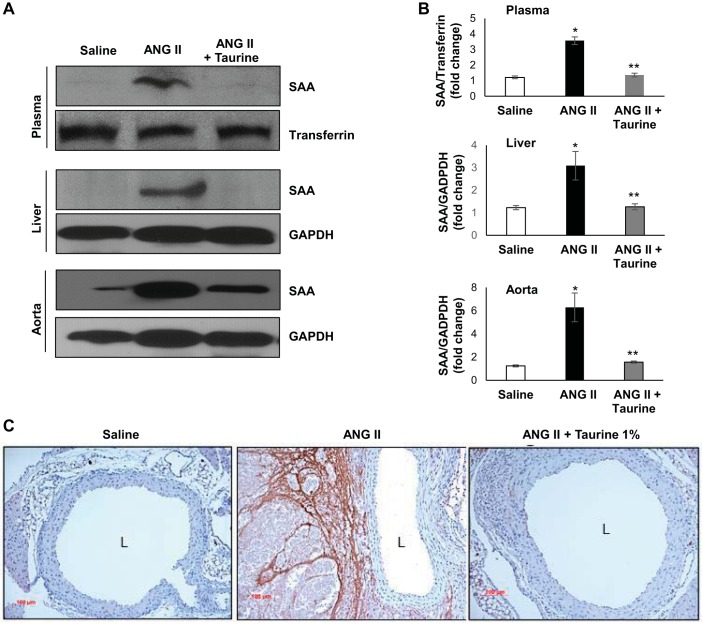

Taurine reduced SAA expression induced during AAA formation.

Given that MPO gene deletion blocked induction of SAA during AAA formation (Fig. 2) and that taurine reduced peroxidase activity (Fig. 3), we next tested whether taurine supplementation inhibited SAA induction during AAA formation. ANG II infusion into ApoE−/− mice significantly increased SAA levels in the plasma, liver, and aorta, all of which were effectively reduced by taurine supplementation (Fig. 4, A and B). Immunostaining demonstrated that SAA accumulated primarily in the adventitia in aortas of ANG II-infused mice and was effectively blocked by taurine treatment (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Serum amyloid A (SAA) expression levels in apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE−/−) mice treated with or without taurine and infused with ANG II. A: representative Western blot demonstrating effects of ANG II with and without taurine supplementation on SAA protein expression in the plasma, liver, and aorta. Transferrin and GAPDH are shown as loading controls. B: densitometric analysis of SAA protein expression. *P < 0.01 vs. saline; **P < 0.01 vs. ANG II (n = 3). C: representative images of aortic SAA immunostaining in mice treated with or without taurine supplementation. L, lumen.

Taurine and MPO gene deletion protected against elastase-induced AAA formation.

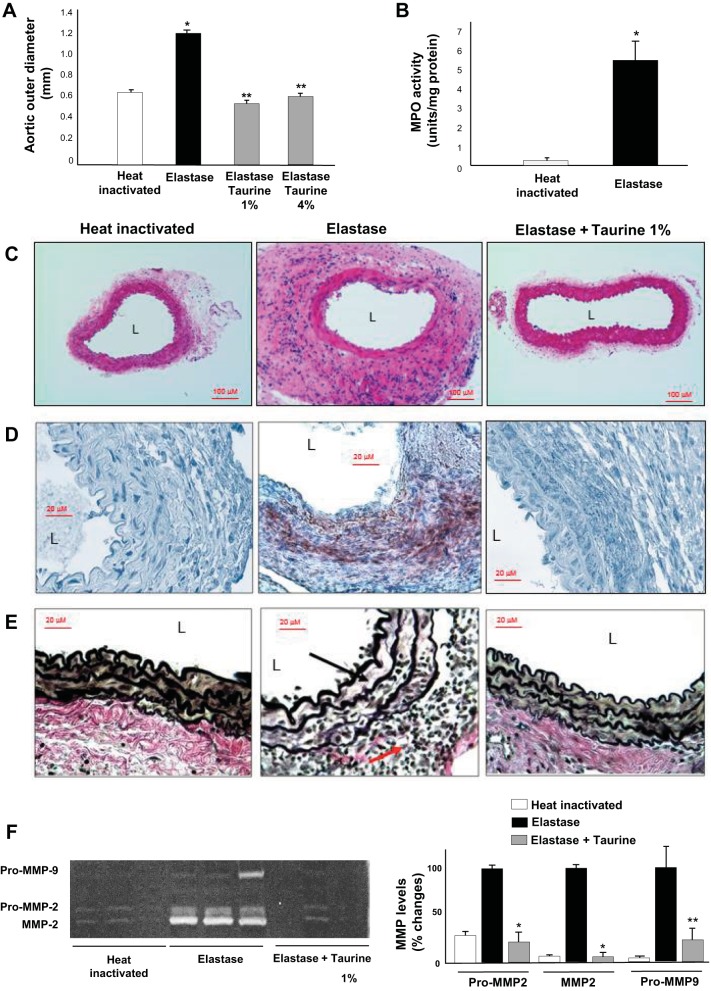

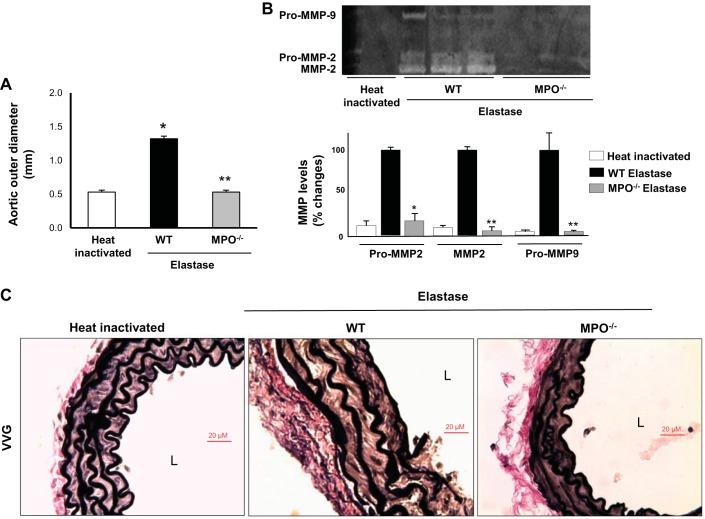

We next investigated whether taurine inhibited AAA formation using a distinct model, elastase-induced AAA formation. Elastase infusion produced ~80% increase in aortic diameter compared with control, and taurine supplementation prevented elastase-induced AAA formation (Fig. 5A). Peroxidase activity assay showed marked increases in aortas extracted from mice 3 days after elastase infusion compared with aortas from mice infused with heat-inactivated elastase (Fig. 5B). This was consistent with previous observations and corresponds to the time point of maximal aortic PMN accumulation in this experimental model (26). Tissue histology showed prominent macrophage accumulation in the adventitia of elastase-infused aortas that was blunted by taurine supplementation (Fig. 5, C and D). In addition, elastase infusion strongly induced elastin degradation (Fig. 5D) and aortic MMP-2/MMP-9 activation (Fig. 5E), which were also blocked by taurine supplementation. Similar to our findings with taurine, deletion of MPO also strongly protected mice against AAA formation in the elastase model (Fig. 6A). MMP-2/MMP-9 activation (Fig. 6B) and elastin fragmentation (Fig. 6C) were diminished markedly in MPO−/− mice compared with WT control mice.

Fig. 5.

Effects of taurine supplementation on elastase-induced abdominal aortic aneurysms. A: myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity in aortic segments from mice infused with native or heat-inactivated elastase. B: mean outer aortic diameters in elastase-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm mice with or without taurine supplementation [1% or 4% (wt/vol)] in drinking water. *P < 0.05 vs. heat-inactivated control; **P < 0.05 vs. elastase (n = 8). C: representative hematoxylin and eosin staining in aortic tissues from mice infused native or heat-inactivated elastase or elastase with taurine [1% (wt/vol)] supplementation. D: representative Mac-3 macrophage immunostaining in aortic tissues. E: representative Verhoeff van Gieson elastin staining in aortic segments. Black arrow indicates elastin; red arrow indicates inflammatory cells. F: representative zymogram (left) demonstrating aortic pro-matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, MMP-2, and pro-MMP-9 levels and quantified data (right). L, lumen. *P < 0.01 and **P < 0.05 vs. elastase (n = 3).

Fig. 6.

Characterization of elastase-induced abdominal aortic aneurysms in wild-type (WT) mice versus myeloperoxidase (MPO)−/− mice. A: mean outer aortic diameter after elastase infusion in WT mice and MPO−/− mice. *P < 0.05 vs. heat-inactivated control; **P < 0.05 vs. elastase-infused WT (n = 8). B: representative zymogram (top) of pro-matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, MMP-2, and pro-MMP-9 levels and quantified data (bottom). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 vs. elastase (n = 3). C: Verhoeff van Gieson (VVG) elastin staining in the aortas from WT mice or MPO−/− mice infused with elastase. L, lumen.

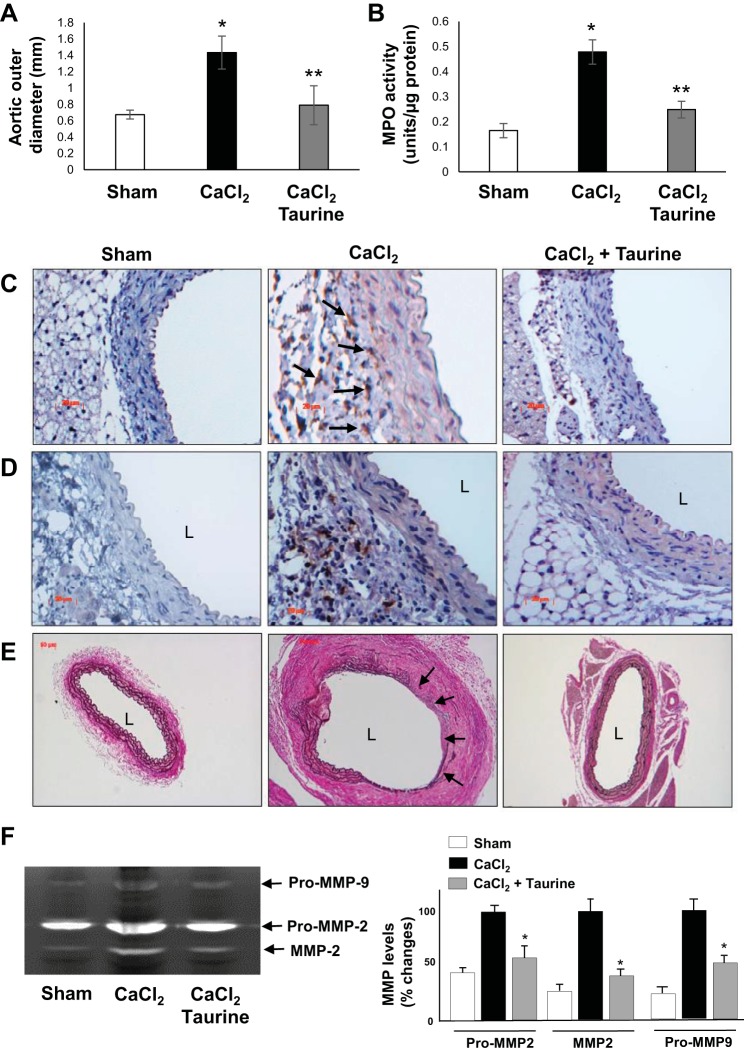

Taurine protected against CaCl2-induced AAA formation.

We further investigated whether taurine treatment could mitigate AAA formation induced by CaCl2 application in C57BL/6 mice, another animal model of AAA, which is associated with PMN infiltration and elastin fragmentation. As shown in Fig. 7, A and B, taurine treatment significantly reduced aortic diameter and MPO activity induced by CaCl2 application. Prominent elastin fragmentation, macrophage infiltration, and MPO accumulation were observed in CaCl2-induced AAA tissues compared with sham control tissues, which were markedly inhibited by taurine treatment (Fig. 7, C–E). Furthermore, taurine blocked induction of aortic MMP-2/MMP-9 by CaCl2 application (Fig. 7F).

Fig. 7.

Effects of taurine on CaCl2-induced abdominal aortic aneurysms in wild-type (WT) mice. A and B: effects of taurine on mean outer aortic diameter (A) and myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity (B). *P < 0.05 vs. sham control; **P < 0.05 vs. CaCl2-treated WT mice (A: n = 10, B: n = 3). C−E: representative histology demonstrating elastin degradation (C; Verhoeff van Gieson staining), macrophage infiltration (D; Mac-3 staining), and MPO accumulation (E). Black arrows indicate macrophages (C) and elastin degradation (E). L, lumen. F: representative zymogram (left) of pro-matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, MMP-2, and pro-MMP-9 levels as well as quantified data (right). *P < 0.05 vs. CaCl2 (n = 3).

DISCUSSION

Oxidative stress is hypothesized to exert a prominent role in AAA pathogenesis (23). MPO, an enzyme expressed predominantly in PMNs and monocytes, is an important mediator of vascular oxidative stress, and its levels have been positively associated with AAA in humans (12, 19). Here, using three distinct animal models of AAA, we report that deletion of MPO or supplementation with taurine, a naturally occurring amino acid that is reported to ameliorate MPO-mediated oxidative stress, mitigates AAA formation. Mechanistically, both MPO gene deletion and taurine supplementation blunted aortic macrophage accumulation, elastin fragmentation, and MMP activation, key features of AAA pathogenesis. Moreover, induction of SAA, which amplifies inflammation and activates MMPs and has been implicated in AAA (42), was strongly attenuated by MPO gene deletion and taurine supplementation. These data implicate MPO in the pathogenesis of AAA and raise the possibility that taurine supplementation be evaluated for its therapeutic efficacy in subjects with AAA.

The contribution of MPO to vascular disease was supported by previous studies that identified MPO-oxidized molecular species in human atherosclerotic plaques (2, 9, 13, 46). In the circulation, MPO is bound tightly to and oxidatively modifies high-density lipoprotein (HDL), thereby disrupting its antiatherogenic effects (13, 47). MPO levels are independently associated with the presence of coronary artery disease, linked to catalytic consumption of nitric oxide and endothelial dysfunction in vivo, and are predictive of future myocardial infarction and major adverse cardiac and peripheral arterial events (2, 39). Interestingly, studies using genetically modified mice to examine a role of MPO in atherosclerosis have produced variable results (38). This discrepancy between murine studies and human data may, in part, reflect species differences in MPO, since murine leukocytes contain ~10-fold less MPO than human leukocytes (28).

The potential role of MPO in AAA has received little attention despite the compelling evidence linking PMNs to the pathogenesis of AAA in humans. For example, PMNs isolated from patients with AAA are activated, release more MPO, and exhibit higher intracellular H2O2 levels compared with controls, suggesting a fundamental state of redox imbalance (12, 29, 30). These PMNs become trapped within the thrombus associated with AAA and release MPO, plasma levels of which are also elevated in patients with AAA (12, 30). Smoking, a major risk factor for AAA, upregulates MPO expression and activity in PMNs, and MPO upregulation was also observed after in vitro exposure of PMNs to nicotine (21). Interestingly, nicotine infusion was demonstrated to promote AAA in mice (40), which further suggests a biological link between smoking, PMNs, MPO, and AAA.

Here, we used three murine models of AAA formation to test the hypothesis that MPO contributes to AAA pathogenesis. In the elastase and CaCl2 models, PMN infiltration is prominent, and aortic MPO accumulation precedes onset of aneurysm formation (5, 26). These findings, coupled with our data showing that MPO gene deletion or taurine supplementation prevented elastin- and CaCl2-induced AAA, provide strong support for our hypothesis. However, unlike the elastase or CaCl2 models, PMN infiltration is not a prominent feature of the ANG II infusion model (32), although PMNs can become trapped within the thrombus that forms in the media. Biochemical and histological analyses demonstrated evidence of increased peroxidase activity and MPO protein, respectively, in aortas from ANG II-infused mice; immunostaining specificity was established using tissues from MPO knockout mice. The diffuse pattern of immunostaining suggests MPO expression by macrophages prevalent in the vascular wall and/or tissue uptake in response to ANG II infusion, a hypothesis that will need to be addressed in future studies.

MPO uses H2O2 to convert l-tyrosine to tyrosyl radical. Activated PMNs use this system to oxidize free l-tyrosine to o,o’-diTyr, and levels of protein-bound diTyr are elevated in atherosclerotic tissues (9, 15, 19). In this study, diTyr levels measured by LC/MS/MS were markedly increased in AAA tissues in conjunction with increased peroxidase activity. Attenuation of ANG II-induced AAA by taurine was associated with diminished peroxidase activity and diTyr levels, consistent with inhibiting MPO, although taurine possesses other biological actions that could favorably modulate AAA (25).

SAA is a cytokine-inducible, acute-phase reactant, expressed primarily in hepatocytes, inflammatory cells, and adipocytes. Plasma SAA concentrations are elevated in chronic inflammatory diseases, and both SAA and MPO can circulate bound to HDL. Our findings of increased SAA levels in the liver, plasma, and aorta in the ANG II-induced AAA model confirm the findings of Webb et al. (42), who proceeded to demonstrate a key role for SAA in the pathogenesis of AAA using SAA1/2 knockout mice. Here, we show that MPO gene deletion and taurine treatment prevented upregulation of SAA during ANG II infusion, suggesting that MPO may promote AAA, at least in part, through SAA induction. The extent to which local versus hepatic production of SAA contributes to aortic pathology remains to be determined. Interestingly, MPO gene deletion attenuated hepatic inflammation in mice fed a high-fat diet, which may support a role for MPO in regulating SAA expression in liver (31). Moreover, increased plasma levels of circulating inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α during AAA formation may contribute to liver inflammation and induction of hepatic SAA expression. Indepth studies are required in the future to determine the mechanisms of SAA regulation by MPO.

Taurine supplementation is generally regarded as safe, is thought to function through inhibition of oxidative stress, and has been provided in doses up to 10 g/day administered for 6–12 mo with minimal adverse effects (34). Oral taurine (3 g/day) ameliorated lipid-induced oxidative stress and insulin resistance in obese, nondiabetic men (44). Moreover, supplementation with 6 g/day taurine reduced oxidative DNA damage in leukocytes measured 24 h after intense aerobic exercise (45). Taurine supplementation also improved parameters of cardiovascular dysfunction in smokers, such as endothelial cell function and viability (6). Our findings suggest that taurine supplementation mitigates AAA formation in three distinct murine models. Given taurine’s safety record and low cost, it merits consideration for efficacy testing in patients with AAA.

In conclusion, we report, for the first time, that the neutrophil enzyme MPO, levels of which are elevated in plasma and aneurysm tissues of patients with AAA, plays a pivotal role in AAA formation induced experimentally in mice using pathogenically distinct models of aneurysm formation. Moreover, supplementation with taurine, a naturally occurring amino acid, which is safe and effective at ameliorating MPO-mediated oxidative stress, can mitigate experimental AAA formation. Further studies are indicated to test the effects of taurine supplementation on parameters of MPO-mediated oxidative stress and AAA progression in patients with this disorder.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-076684, HL-62984, HL-105675, and HL-112640 (to N. L. Weintraub) and P01 HL076491 (S. L. Hazen) and by Department of Defense Grant NF-140031 (B. K. Stansfield).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

H.W.K., A.L.B., and N.L.W. conceived and designed research; H.W.K., A.L.B., M.O., D.G., B.S.N., V.M.B., M.L.M., and X.F. performed experiments; H.W.K., A.L.B., M.O., M.T., D.G., B.S.N., R.W.T., R.M.W., V.M.B., M.L.M., A.D., X.F., S.L.H., B.K.S., D.J.F., T.C., and N.L.W. analyzed data; H.W.K., A.L.B., M.O., M.T., D.G., B.S.N., L.A.C., R.W.T., R.M.W., P.D.L., V.M.B., M.L.M., A.D., S.L.H., B.K.S., Y.H., D.J.F., T.C., and N.L.W. interpreted results of experiments; H.W.K., A.L.B., and M.O. prepared figures; H.W.K., A.L.B., and N.L.W. drafted manuscript; H.W.K., A.L.B., M.T., D.G., L.A.C., R.W.T., R.M.W., P.D.L., V.M.B., M.L.M., A.D., S.L.H., B.K.S., Y.H., D.J.F., T.C., and N.L.W. edited and revised manuscript; H.W.K., A.L.B., M.O., M.T., D.G., B.S.N., L.A.C., R.W.T., R.M.W., P.D.L., V.M.B., M.L.M., A.D., X.F., S.L.H., B.K.S., Y.H., D.J.F., T.C., and N.L.W. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brennan ML, Wu W, Fu X, Shen Z, Song W, Frost H, Vadseth C, Narine L, Lenkiewicz E, Borchers MT, Lusis AJ, Lee JJ, Lee NA, Abu-Soud HM, Ischiropoulos H, Hazen SL. A tale of two controversies: defining both the role of peroxidases in nitrotyrosine formation in vivo using eosinophil peroxidase and myeloperoxidase-deficient mice, and the nature of peroxidase-generated reactive nitrogen species. J Biol Chem 277: 17,415–17,427, 2002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112400200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brennan ML, Penn MS, Van Lente F, Nambi V, Shishehbor MH, Aviles RJ, Goormastic M, Pepoy ML, McErlean ES, Topol EJ, Nissen SE, Hazen SL. Prognostic value of myeloperoxidase in patients with chest pain. N Engl J Med 349: 1595–1604, 2003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brewster DC, Cronenwett JL, Hallett JW Jr, Johnston KW, Krupski WC, Matsumura JS; Joint Council of the American Association for Vascular Surgery and Society for Vascular Surgery . Guidelines for the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Report of a subcommittee of the joint council of the American Association for Vascular Surgery and Society for Vascular Surgery. J Vasc Surg 37: 1106–1117, 2003. doi: 10.1067/mva.2003.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carr AC, Hawkins CL, Thomas SR, Stocker R, Frei B. Relative reactivities of N-chloramines and hypochlorous acid with human plasma constituents. Free Radic Biol Med 30: 526–536, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(00)00495-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eliason JL, Hannawa KK, Ailawadi G, Sinha I, Ford JW, Deogracias MP, Roelofs KJ, Woodrum DT, Ennis TL, Henke PK, Stanley JC, Thompson RW, Upchurch GR Jr. Neutrophil depletion inhibits experimental abdominal aortic aneurysm formation. Circulation 112: 232–240, 2005. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.517391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fennessy FM, Moneley DS, Wang JH, Kelly CJ, Bouchier-Hayes DJ. Taurine and vitamin C modify monocyte and endothelial dysfunction in young smokers. Circulation 107: 410–415, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000046447.72402.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gavrila D, Li WG, McCormick ML, Thomas M, Daugherty A, Cassis LA, Miller FJ Jr, Oberley LW, Dellsperger KC, Weintraub NL. Vitamin E inhibits abdominal aortic aneurysm formation in angiotensin II-infused apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25: 1671–1677, 2005. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000172631.50972.0f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hagar HH. The protective effect of taurine against cyclosporine A-induced oxidative stress and hepatotoxicity in rats. Toxicol Lett 151: 335–343, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hazen SL, Heinecke JW. 3-Chlorotyrosine, a specific marker of myeloperoxidase-catalyzed oxidation, is markedly elevated in low-density lipoprotein isolated from human atherosclerotic intima. J Clin Invest 99: 2075–2081, 1997. doi: 10.1172/JCI119379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hazen SL, Zhang R, Shen Z, Wu W, Podrez EA, MacPherson JC, Schmitt D, Mitra SN, Mukhopadhyay C, Chen Y, Cohen PA, Hoff HF, Abu-Soud HM. Formation of nitric oxide-derived oxidants by myeloperoxidase in monocytes: pathways for monocyte-mediated protein nitration and lipid peroxidation in vivo. Circ Res 85: 950–958, 1999. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.85.10.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heinecke JW, Hsu FF, Crowley JR, Hazen SL, Leeuwenburgh C, Mueller DM, Rasmussen JE, Turk J. Detecting oxidative modification of biomolecules with isotope dilution mass spectrometry: sensitive and quantitative assays for oxidized amino acids in proteins and tissues. Methods Enzymol 300: 124–144, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(99)00121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Houard X, Touat Z, Ollivier V, Louedec L, Philippe M, Sebbag U, Meilhac O, Rossignol P, Michel JB. Mediators of neutrophil recruitment in human abdominal aortic aneurysms. Cardiovasc Res 82: 532–541, 2009. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Y, DiDonato JA, Levison BS, Schmitt D, Li L, Wu Y, Buffa J, Kim T, Gerstenecker GS, Gu X, Kadiyala CS, Wang Z, Culley MK, Hazen JE, Didonato AJ, Fu X, Berisha SZ, Peng D, Nguyen TT, Liang S, Chuang CC, Cho L, Plow EF, Fox PL, Gogonea V, Tang WH, Parks JS, Fisher EA, Smith JD, Hazen SL. An abundant dysfunctional apolipoprotein A1 in human atheroma. Nat Med 20: 193–203, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nm.3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iida Y, Xu B, Xuan H, Glover KJ, Tanaka H, Hu X, Fujimura N, Wang W, Schultz JR, Turner CR, Dalman RL. Peptide inhibitor of CXCL4-CCL5 heterodimer formation, MKEY, inhibits experimental aortic aneurysm initiation and progression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 33: 718–726, 2013. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacob JS, Cistola DP, Hsu FF, Muzaffar S, Mueller DM, Hazen SL, Heinecke JW. Human phagocytes employ the myeloperoxidase-hydrogen peroxide system to synthesize dityrosine, trityrosine, pulcherosine, and isodityrosine by a tyrosyl radical-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem 271: 19950–19956, 1996. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.19950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnston WF, Salmon M, Su G, Lu G, Stone ML, Zhao Y, Owens GK, Upchurch GR Jr, Ailawadi G. Genetic and pharmacologic disruption of interleukin-1β signaling inhibits experimental aortic aneurysm formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 33: 294–304, 2013. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lau D, Baldus S. Myeloperoxidase and its contributory role in inflammatory vascular disease. Pharmacol Ther 111: 16–26, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lederle FA, Johnson GR, Wilson SE, Ballard DJ, Jordan WD Jr, Blebea J, Littooy FN, Freischlag JA, Bandyk D, Rapp JH, Salam AA; Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study #417 Investigators . Rupture rate of large abdominal aortic aneurysms in patients refusing or unfit for elective repair. JAMA 287: 2968–2972, 2002. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.22.2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leeuwenburgh C, Rasmussen JE, Hsu FF, Mueller DM, Pennathur S, Heinecke JW. Mass spectrometric quantification of markers for protein oxidation by tyrosyl radical, copper, and hydroxyl radical in low density lipoprotein isolated from human atherosclerotic plaques. J Biol Chem 272: 3520–3526, 1997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liao F, Andalibi A, Qiao JH, Allayee H, Fogelman AM, Lusis AJ. Genetic evidence for a common pathway mediating oxidative stress, inflammatory gene induction, and aortic fatty streak formation in mice. J Clin Invest 94: 877–884, 1994. doi: 10.1172/JCI117409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loke WM, Lam KM, Chong WL, Chew SE, Quek AM, Lim EC, Seet RC. Products of 5-lipoxygenase and myeloperoxidase activities are increased in young male cigarette smokers. Free Radic Res 46: 1230–1237, 2012. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2012.701291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manning MW, Cassis LA, Huang J, Szilvassy SJ, Daugherty A. Abdominal aortic aneurysms: fresh insights from a novel animal model of the disease. Vasc Med 7: 45–54, 2002. doi: 10.1191/1358863x02vm413ra. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCormick ML, Gavrila D, Weintraub NL. Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27: 461–469, 2007. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000257552.94483.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller FJ Jr, Sharp WJ, Fang X, Oberley LW, Oberley TD, Weintraub NL. Oxidative stress in human abdominal aortic aneurysms: a potential mediator of aneurysmal remodeling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 22: 560–565, 2002. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000013778.72404.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oudit GY, Trivieri MG, Khaper N, Husain T, Wilson GJ, Liu P, Sole MJ, Backx PH. Taurine supplementation reduces oxidative stress and improves cardiovascular function in an iron-overload murine model. Circulation 109: 1877–1885, 2004. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124229.40424.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pagano MB, Bartoli MA, Ennis TL, Mao D, Simmons PM, Thompson RW, Pham CT. Critical role of dipeptidyl peptidase I in neutrophil recruitment during the development of experimental abdominal aortic aneurysms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 2855–2860, 2007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606091104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park HS, Choi GH, Hahn S, Yoo YS, Lee JY, Lee T. Potential role of vascular smooth muscle cell-like progenitor cell therapy in the suppression of experimental abdominal aortic aneurysms. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 431: 326–331, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.12.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Podrez EA, Abu-Soud HM, Hazen SL. Myeloperoxidase-generated oxidants and atherosclerosis. Free Radic Biol Med 28: 1717–1725, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(00)00229-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramos-Mozo P, Madrigal-Matute J, Martinez-Pinna R, Blanco-Colio LM, Lopez JA, Camafeita E, Meilhac O, Michel J-B, Aparicio C, Vega de Ceniga M, Egido J, Martín-Ventura JL. Proteomic analysis of polymorphonuclear neutrophils identifies catalase as a novel biomarker of abdominal aortic aneurysm: potential implication of oxidative stress in abdominal aortic aneurysm progression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31: 3011–3019, 2011. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.237537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramos-Mozo P, Madrigal-Matute J, Vega de Ceniga M, Blanco-Colio LM, Meilhac O, Feldman L, Michel J-B, Clancy P, Golledge J, Norman PE, Egido J, Martin-Ventura JL. Increased plasma levels of NGAL, a marker of neutrophil activation, in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm. Atherosclerosis 220: 552–556, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rensen SS, Bieghs V, Xanthoulea S, Arfianti E, Bakker JA, Shiri-Sverdlov R, Hofker MH, Greve JW, Buurman WA. Neutrophil-derived myeloperoxidase aggravates non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. PLoS One 7: e52411, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saraff K, Babamusta F, Cassis LA, Daugherty A. Aortic dissection precedes formation of aneurysms and atherosclerosis in angiotensin II-infused, apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 23: 1621–1626, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000085631.76095.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schaffer SW, Azuma J, Mozaffari M. Role of antioxidant activity of taurine in diabetes. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 87: 91–99, 2009. doi: 10.1139/Y08-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shao A, Hathcock JN. Risk assessment for the amino acids taurine, l-glutamine and l-arginine. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 50: 376–399, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimada K, Jong CJ, Takahashi K, Schaffer SW. Role of ROS production and turnover in the antioxidant activity of taurine. Adv Exp Med Biol 803: 581–596, 2015. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-15126-7_47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas M, Gavrila D, McCormick ML, Miller FJ Jr, Daugherty A, Cassis LA, Dellsperger KC, Weintraub NL. Deletion of p47phox attenuates angiotensin II-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm formation in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation 114: 404–413, 2006. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.607168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson RW. Detection and management of small aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med 346: 1484–1486, 2002. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200205093461910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tiyerili V, Camara B, Becher MU, Schrickel JW, Lütjohann D, Mollenhauer M, Baldus S, Nickenig G, Andrié RP. Neutrophil-derived myeloperoxidase promotes atherogenesis and neointima formation in mice. Int J Cardiol 204: 29–36, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.11.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vita JA, Brennan ML, Gokce N, Mann SA, Goormastic M, Shishehbor MH, Penn MS, Keaney JF Jr, Hazen SL. Serum myeloperoxidase levels independently predict endothelial dysfunction in humans. Circulation 110: 1134–1139, 2004. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140262.20831.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang S, Zhang C, Zhang M, Liang B, Zhu H, Lee J, Viollet B, Xia L, Zhang Y, Zou MH. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase α2 by nicotine instigates formation of abdominal aortic aneurysms in mice in vivo. Nat Med 18: 902–910, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nm.2711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, Rosen H, Madtes DK, Shao B, Martin TR, Heinecke JW, Fu X. Myeloperoxidase inactivates TIMP-1 by oxidizing its N-terminal cysteine residue: an oxidative mechanism for regulating proteolysis during inflammation. J Biol Chem 282: 31826–31834, 2007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704894200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Webb NR, De Beer MC, Wroblewski JM, Ji A, Bailey W, Shridas P, Charnigo RJ, Noffsinger VP, Witta J, Howatt DA, Balakrishnan A, Rateri DL, Daugherty A, De Beer FC. Deficiency of endogenous acute-phase serum amyloid A protects apoE−/− mice from angiotensin II-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 35: 1156–1165, 2015. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xia Y, Zweier JL. Measurement of myeloperoxidase in leukocyte-containing tissues. Anal Biochem 245: 93–96, 1997. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.9940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiao C, Giacca A, Lewis GF. Oral taurine but not N-acetylcysteine ameliorates NEFA-induced impairment in insulin sensitivity and beta cell function in obese and overweight, non-diabetic men. Diabetologia 51: 139–146, 2008. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0859-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang M, Bi LF, Fang JH, Su XL, Da GL, Kuwamori T, Kagamimori S. Beneficial effects of taurine on serum lipids in overweight or obese non-diabetic subjects. Amino Acids 26: 267–271, 2004. doi: 10.1007/s00726-003-0059-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang R, Brennan ML, Fu X, Aviles RJ, Pearce GL, Penn MS, Topol EJ, Sprecher DL, Hazen SL. Association between myeloperoxidase levels and risk of coronary artery disease. JAMA 286: 2136–2142, 2001. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.17.2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zheng L, Nukuna B, Brennan ML, Sun M, Goormastic M, Settle M, Schmitt D, Fu X, Thomson L, Fox PL, Ischiropoulos H, Smith JD, Kinter M, Hazen SL. Apolipoprotein A-I is a selective target for myeloperoxidase-catalyzed oxidation and functional impairment in subjects with cardiovascular disease. J Clin Invest 114: 529–541, 2004. doi: 10.1172/JCI200421109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]