Abstract

In addition to their intended clinical actions, all general anesthetic agents in common use have detrimental intrasurgical and postsurgical side effects on organs and systems, including the heart. The major cardiac side effect of anesthesia is bradycardia, which increases the probability of insufficient systemic perfusion during surgery. These side effects also occur in all vertebrate species so far examined, but the underlying mechanisms are not clear. The zebrafish heart is a powerful model for studying cardiac electrophysiology, employing the same pacemaker system and neural control as do mammalian hearts. In this study, isolated zebrafish hearts were significantly bradycardic during exposure to the vapor anesthetics sevoflurane (SEVO), desflurane (DES), and isoflurane (ISO). Bradycardia induced by DES and ISO continued during pharmacological blockade of the intracardiac portion of the autonomic nervous system, but the chronotropic effect of SEVO was eliminated during blockade. Bradycardia evoked by vagosympathetic nerve stimulation was augmented during DES and ISO exposure; nerve stimulation during SEVO exposure had no effect. Together, these results support the hypothesis that the cardiac chronotropic effect of SEVO occurs via a neurally mediated mechanism, while DES and ISO act directly upon cardiac pacemaker cells via an as yet unknown mechanism.

Keywords: autonomic nervous system, intracardiac nervous system, isoflurane, desflurane, sevoflurane

anesthetic agents act at multiple cellular targets to cause widespread depression within the vertebrate central nervous system (CNS). These agents evoke unconsciousness, immobility, and inhibition of sensory inputs (17, 18, 25, 38), thereby, allowing invasive surgeries and experimental procedures to be performed.

In addition to their desired effects, all general anesthetic agents in common use also have a broad array of detrimental intraprocedural and postprocedural side effects on organs and systems, including the nervous system and heart (21, 49). Anesthetics can suppress or compromise autonomically regulated homeostatic functions (such as breathing, heartbeat, and blood pressure) to varying degrees (38). Ligand-gated receptor mechanisms and ion channels, upon which general anesthetics act in the CNS, are also present in peripheral components of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), including the intracardiac nervous system (ICNS), which forms a “final common pathway” for neural control of the vertebrate heart (2, 54). Furthermore, many of the same receptors and channels are present on cardiac myocytes and atrial pacemaker cells, so circulating anesthetics may also act directly on these cells. Thus, it is not surprising that cardiac side effects of general anesthetics have been documented in species from fishes to mammals. Such side effects include dose- and exposure time-dependent heart rate changes, arrhythmias, and alterations in electrocardiogram (ECG) properties, conduction, and myocardial contractility, which together culminate in reduced cardiac output (1, 5, 10, 20, 48, 52). The major cardiac side effect of anesthesia is bradycardia, or reduction in heart rate, which increases the danger that the heart will not be able to supply sufficient blood to the body tissues during the period of anesthesia. The causes of the cardiovascular side effects of anesthetics are, however, not clear in any vertebrate species (see Ref. 17).

The zebrafish is being increasingly used as a model organism for the assessment of drug- and anesthetic-induced heart rate effects (7, 27, 39). Recent reports have described significant advantages of the zebrafish model over more traditional mammalian models, such as rodent, canine, or porcine species for evaluating cardiac function and dysfunction (6, 55). These advantages include reduced expense, the requirement for smaller amounts of test compounds, and the possibility for increased sample sizes (6). Furthermore, the operation of the fish heart is fundamentally similar to that of mammals, matching cardiac output to blood perfusion requirements and employing the same pacemaker system and its neural control (54, 55). The basic structure of the ICNS in zebrafish has been described (54) and is consistent with that of humans and common mammalian models (30, 33, 35, 41–43). Furthermore, the physiological aspects of the neural control of chronotropy in the isolated zebrafish heart have been described (55). Thus, the in vitro zebrafish heart provides an ideal model for investigating cardiac responses to anesthetic agents, independent of influences from other factors within the body that may complicate experiments on cardiac function in vivo.

In the current study, isolated zebrafish hearts were exposed to vapor anesthetics over a range of doses to determine their effects on heart rate (HR), measured by quantification of interbeat [R-wave to R-Wave (R-R)] intervals, and conduction, as measured by atrioventricular delay (AVd) in recorded ECGs. Autonomic antagonists were used to block neural influences to investigate the relative contributions of neural vs. myocardial mechanisms involved in the disruption of heart rate by anesthetics. The results of the current study provide a new model to further our understanding of the mechanisms of cardiotropic effects of modern anesthetics, which is critical to advancing our understanding of the control of cardiac output during anesthesia.

METHODS

Ethical approval.

Institutional approval for animal use was provided by the Dalhousie University Committee on Laboratory Animals (protocol no. 14–021) following guidelines for animal care issued by the Canadian Council of Animal Care (2005).

Animals.

A total of 72 adult, AB wild-type zebrafish (12–18 mo postfertilization) of both sexes was used in this study. Animals were housed in 3- to 10-liter tanks (AquaticHabitats, Apopka, FL) at 28.5°C on a 14:10-h light-dark cycle and fed commercial pellet food (BrineShrimp Direct, Ogden, UT) twice a day. Filtered, conditioned water was continuously supplied from a recirculating system.

Heart isolation.

Zebrafish were anesthetized in a buffered solution (pH 7.2) of tricaine (MS-222; 1.5 mM; Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, ON, Canada) in tank water (28.5°C), and hearts were isolated as previously described (55).

Measurement of heart rate and vagosympathetic nerve electrical stimulation.

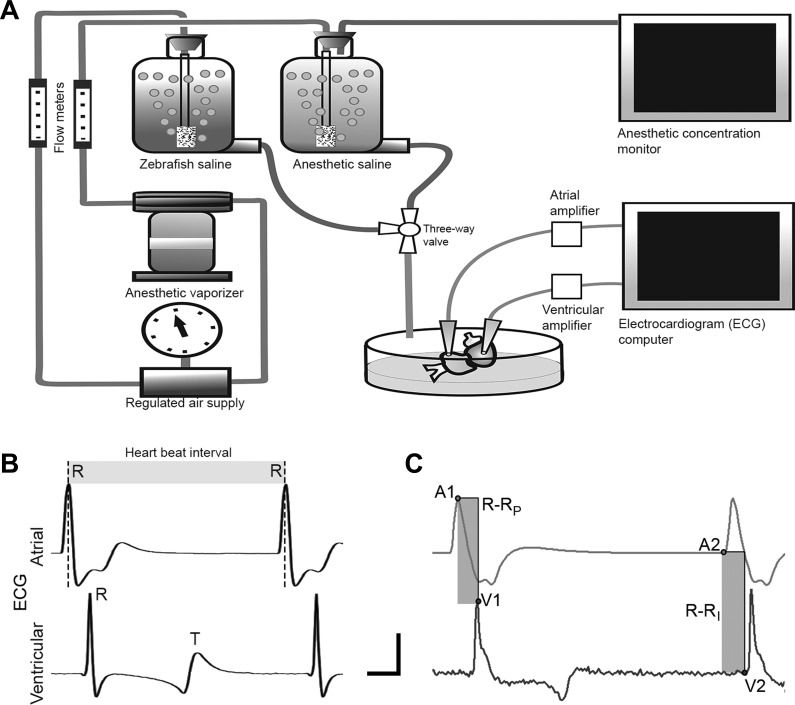

Isolated hearts were pinned to the Sylgard rubber (Dow Corning, Midland, MI) bottom of a 5-ml chamber (Fig. 1A) and superfused (10 ml/min) with zebrafish saline (composition in mM: 124.1 NaCl, 5.1 KCl, 2.9 Na2HPO4, 1.9 MgSO·7H2O, 1.4 CaCl2·2H2O, 11.9 NaHCO3; aerated with room air; pH 7.2; 25°C, see details in results). Hearts were allowed to equilibrate in the bath for 30 min before testing, to ensure stable HR and to allow for washout of any residual tricaine (see Potential postisolation effects of tricaine). ECG signals were recorded from the surface of the free walls of the atrium and ventricle via bipolar suction electrodes (Fig. 1A) placed at standardized locations to ensure consistent ECG waveforms across all preparations. For atrial recordings, the electrode was placed on the wall ~250 µm from the sinoatrial region (halfway between the sinoatrial and atrioventricular regions). Ventricular recordings were made at a position ~500 µm from the atrioventricular funnel (halfway between the funnel and the ventricular apex). ECG signals were collected (total gain × 1,000–10,000, sampling rate 5 kHz, 0.1-Hz low-pass filter, 3-kHz high-pass filter) and stored on a personal computer after analog-to-digital conversion (Digidata 1322A; Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). To quantify cardiac responses, data were processed to measure time between adjacent R-waves of the ECG (R-R interval, Fig. 1B), and latency between atrial and ventricular R-waves within individual cardiac cycles (AVd; Fig. 1C; see Ref. 55) using Axoscope software (Axon Instruments). It was possible that, despite precautions taken to standardize the recording of the ECG, there could have been variations in estimating AVd due to small changes in the waveform shape during an experiment. To control for this, in a subset of the experiments, AVd was calculated either as the time from atrial R-wave peak to ventricular R-wave peak (R-RP, Fig. 1C) or from the inflection point from the baseline of the atrial R-wave to the inflection point of the ventricular R-wave (R-RI, Fig. 1C). The results of these methods of estimating AVd are summarized in Table 1. Estimates of AVd did not differ significantly between these methods, so we used the R-RP method in this study.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the perfusion and electrocardiogram (ECG) recording system for the isolated zebrafish heart. A: standard zebrafish saline or zebrafish saline including one of desflurane (DES), isoflurane (ISO), or sevoflurane (SEVO) was delivered to the heart from gravity-fed reservoirs, with the perfusate path controlled by a three-way valve. Cardiac electrical activity was monitored via surface ECG, from bipolar atrial and ventricular leads (see text for details of lead placement), differentially amplified, and recorded on a PC. Anesthetic concentration was monitored via a gas-chromatograph patient monitor. B: sample ECG recordings from atrial and ventricular leads, showing R- and T-waves. Chronotropic responses were quantified by changes in the interbeat interval (R-R; shaded area) calculated from the time between atrial R peaks. C: atrioventricular delay was quantified using two methods to estimate the time difference between atrial and ventricular R peaks within a cardiac cycle (shaded areas). R-RP represents time difference between R-wave peaks at points labeled A1, V1; R-RI represents time difference between the R-wave inflection points from baseline (A2, V2). AVd estimated by these methods did not differ statistically (see text for details). Vertical bar represents 5 mV, while horizontal bar represents 0.1 s.

Table 1.

Raw data comparing estimates of AV delay taken from R-RP with AV delay from R-RI

| 15 min, 1.0 MAC |

15 min, 2.5 MAC |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-RP, ms | R-RP, AVG | R-RI, ms | R-RI AVG | R-RP, ms | R-RP AVG | R-RI, ms | R-RI AVG | ||

| Desflurane | |||||||||

| Pre-DES | F1 | 55 | 52 ± 3 | 55 | 52 ± 3 | 51 | 51 ± 1 | 51 | 51 ± 1 |

| F2 | 55 | 60 | 52 | 52 | |||||

| F3 | 55 | 55 | 56 | 55 | |||||

| F4 | 41 | 41 | 46 | 49 | |||||

| F5 | 46 | 46 | 49 | 46 | |||||

| F6 | 52 | 53 | 51 | 51 | |||||

| DES | F1 | 65 | 62 ± 4 | 65 | 62 ± 3 | 69 | 72 ± 4 | 69 | 72 ± 4 |

| F2 | 69 | 71 | 66 | 68 | |||||

| F3 | 68 | 66 | 66 | 66 | |||||

| F4 | 47 | 48 | 88 | 88 | |||||

| F5 | 53 | 56 | 77 | 77 | |||||

| F6 | 66 | 67 | 66 | 66 | |||||

| Isoflurane | |||||||||

| Pre-ISO | F1 | 56 | 48 ± 2 | 55 | 48 ± 2 | 48 | 54 ± 3 | 48 | 54 ± 3 |

| F2 | 44 | 44 | 64 | 64 | |||||

| F3 | 46 | 45 | 61 | 62 | |||||

| F4 | 44 | 44 | 42 | 41 | |||||

| F5 | 43 | 43 | 50 | 51 | |||||

| F6 | 54 | 54 | 57 | 57 | |||||

| ISO | F1 | 91 | 82 ± 3 | 91 | 82 ± 3 | 98 | 94 ± 6 | 98 | 94 ± 6 |

| F2 | 87 | 87 | 96 | 96 | |||||

| F3 | 77 | 77 | 102 | 102 | |||||

| F4 | 83 | 84 | 107 | 106 | |||||

| F5 | 69 | 68 | 97 | 97 | |||||

| F6 | 87 | 87 | 66 | 67 | |||||

| Sevoflurane | |||||||||

| Pre-SEVO | F1 | 41 | 52 ± 5 | 40 | 55 ± 5 | 41 | 50 ± 4 | 41 | 49 ± 4 |

| F2 | 66 | 64 | 66 | 66 | |||||

| F3 | 59 | 59 | 49 | 49 | |||||

| F4 | 60 | 60 | 58 | 56 | |||||

| F5 | 55 | 55 | 41 | 41 | |||||

| F6 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | |||||

| SEVO | F1 | 77 | 74 ± 4 | 77 | 74 ± 4 | 97 | 95 ± 5 | 97 | 95 ± 5 |

| F2 | 77 | 77 | 115 | 115 | |||||

| F3 | 88 | 88 | 98 | 99 | |||||

| F4 | 71 | 72 | 87 | 88 | |||||

| F5 | 75 | 75 | 97 | 96 | |||||

| F6 | 58 | 56 | 76 | 76 | |||||

Sample traces are shown in Fig. 1C. Data are represented before and during exposure to desflurane (DES), isoflurane (ISO), and sevoflurane (SEVO). Within each data set, there was no significant difference between means derived from atrial R-wave peak to ventricular R-wave peak (R-RP) and the atrial R-wave to the inflection point of the ventricular R-wave (R-RI) (paired Studentʼs t-test, P ≤ 0.05).

Vagosympathetic nerve (VSN) trunks were stimulated with bipolar wire electrodes attached to constant-current isolation units (PSIU6; Grass Instruments, Quincy, MA) driven by a stimulator (Grass S88) delivering trains of rectangular pulses [pulse duration 0.5 ms; train duration 10 s, pulse frequency 15 Hz, stimulus current 300 μA (55)]. In previous work, the effects of left and right VSN stimulation on HR were statistically similar (55), so in this study, only the right VSN was stimulated. To control for the possibility of electrotonic spread of current into the myocardium from the site of nerve stimulation, in some preparations, the stimulating electrodes were placed on the duct wall away from the VSN (n = 6) or moved off the nerve into the bath near the tissue (n = 6). Repeated stimulation with the same parameters had no effect on heart rate.

Potential postisolation effects of tricaine.

Tricaine has previously been reported to alter HR in zebrafish (27), so preliminary experiments were performed to ensure the use of this compound, as the overdose anesthetic for heart isolation did not alter cardiac responses in the present study. Residual tricaine from the initial overdose was washed out for 60 min, and then the hearts were superfused with a 1.5 mM solution of tricaine (equal in concentration to that used in the overdose procedure) for 1 min. Hearts were then switched back to fresh perfusate without tricaine. Heart rate was monitored before, during, and after tricaine exposure. Tricaine exposure caused an increase in mean R-R interval to 1.9 ± 0.12 times the mean preexposure value, and recovery to pretricaine R-R interval occurred by 8.5 ± 1 min after the return to fresh saline. Therefore, a standardized washout time of 30 min was used before all experiments to ensure residual tricaine exposure did not affect the experimental outcomes.

Anesthetic agents.

Desflurane (DES; Baxter, Mississauga, ON, Canada), isoflurane (ISO; Baxter), or sevoflurane (SEVO; Abbott Canada, Saint-Laurent, QC, Canada) was mixed with room air through standard vaporizers (Draegerwerk, Lübeck, Germany) that continuously bubbled anesthetic vapor into a reservoir of zebrafish saline; the tissue was then superfused with this mixture (Fig. 1A). The concentration of each anesthetic in the perfusate was measured by sampling with a standard patient vapor-phase anesthetic monitor (Datex-Ohmeda, Madison, WI) from the air space in the reservoir. The partial pressure of anesthetic in the gas phase and in the perfusate was assumed to be in equilibrium. Anesthetic concentrations were adjusted relative to the “minimum alveolar concentration” (MAC) for that agent (that is, the dose required to maintain a clinical level of anesthesia in patients; Refs. 15 and 25). This dose was designated as “1.0 MAC” in the present study. DES was mixed at 3–12% (6% = 1 MAC), ISO was mixed at 0.75–3% (1.5% = 1 MAC), and SEVO was mixed at 1.0–4.0% (2.0% = 1 MAC) with air through the vaporizers.

Anesthetic test procedures.

Manufacturers of the vapor anesthetics used in this study have stated that these agents have negligible solubility in water. To test anesthetic concentration in the perfusate, samples were drawn at random times during experiments from the anesthetic perfusate reservoir into a sealed container. These samples were allowed to off-gas in air, and the dose of anesthetic present was measured with the patient monitor from the air immediately above the air-liquid interface. Concentrations measured from these off-gassing samples were assumed to be in equilibrium with the perfusate. Values for the measured anesthetic concentrations in these trials were statistically similar to those recorded during the initial setup stage for each experiment (Studentʼs t-test; data not shown), indicating that anesthetic levels in the perfusate were in equilibrium with those sampled from the air-interface during experiments.

In trial studies to determine time-dependent cardiac effects, anesthetic agents were introduced to isolated hearts, and the ECG was recorded for up to 1 h in the presence of a test agent. Each agent evoked a change in R-R period from the control (preanesthetic value), but in these trials, there was no significant difference in R-R interval at 15 min and 1 h of anesthetic exposure (t-test; data not shown). Therefore, in all subsequent experiments, we used a standard period of 15 min for anesthetic exposure.

For concentration-effect studies, trial experiments were done to determine the lowest dose of each anesthetic that altered cardiac rate. After an acclimation period, the minimum dosage that evoked a detectable change in HR over a 30-min exposure period was 0.5 MAC (data not shown). Thus, for the purposes of this study, anesthetics were applied in dosages increasing from 0.5 MAC to 2.5 MAC (the maximum dosage represented the highest concentration that could be delivered by the vaporizers).

As a control for potential effects due to the anesthetic vaporizer itself, in trial experiments, hearts were superfused with saline that had been bubbled through the vaporizer system with no anesthetic present. The results of these trials showed that cardiac responses occurred only when the vaporizer was delivering anesthetic to the perfusate. Thus, it was assumed that the observed chronotropic effects were, in fact, due to the anesthetic agents reaching the isolated heart.

Pharmacological agents.

Atropine (ATR; postjunctional muscarinic receptor blocker; 10 μM; Sigma Aldrich) and timolol (TIM; postjunctional β-adrenergic receptor blocker; 100 μM; Sigma Aldrich) were dissolved in perfusate on the day of experiments (55). For experiments investigating autonomic blockade, these drugs were delivered starting at 15 min before and continuing through the period of anesthetic delivery. Two trial paradigms were used to test whether the order of exposure to antagonist alone and in combination with an anesthetic could have evoked different cardiac outcomes. In the first trial, hearts were exposed to the antagonists alone and then to anesthetic with the antagonists. In the second trial, hearts were exposed to anesthetic alone and then to the antagonists with anesthetic. Analysis of the chronotropic effects of these paradigms indicated that the order of exposure made no significant difference (data not shown). Thus, in all subsequent experiments, responses were first measured during antagonist exposure alone, then with antagonist and anesthetic.

Data analyses.

Data are presented as means ± SE with ranges. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc, Student’s t-test with Bonferroni corrections, or linear regression were used to analyze the data, using IBM SPSS software (IBM Analytics Canada, Markham, ON, Canada). P values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Heart function in vitro.

Mean initial HR was 103 ± 13 beats/min (range 77–166), and mean initial AVd was 52 ± 2 ms (range 40–70 ms), values that correlate well with those previously reported for zebrafish (34, 55). For the purposes of the experiments in this study, control HR and AVd for each treatment were taken as the values measured immediately before applying each treatment, and responses are presented as changes during anesthetic exposure relative to preexposure values. To ensure that variation in temperature of the perfusate was not a confounding factor, temperature of the bath was monitored immediately before and at random times throughout each experiment. Average bath temperature was 24.8 ± 0.1°C (range 24–25.9°C). Given a previously reported Q10 for HR in zebrafish of ~1.7 (34), the change in HR due to variations in temperature would be negligible in comparison to the effects observed with anesthetics in the current study.

Time course of anesthetic-induced changes in HR and AVd.

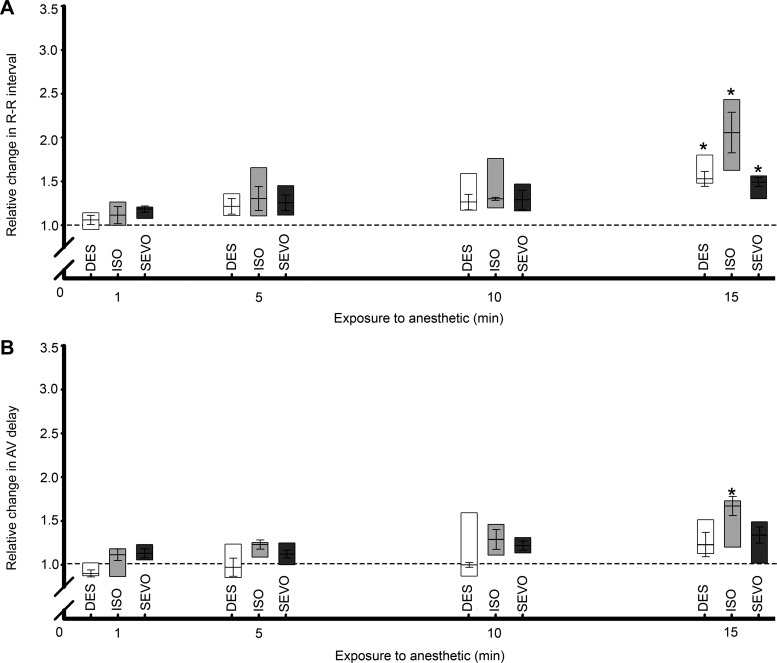

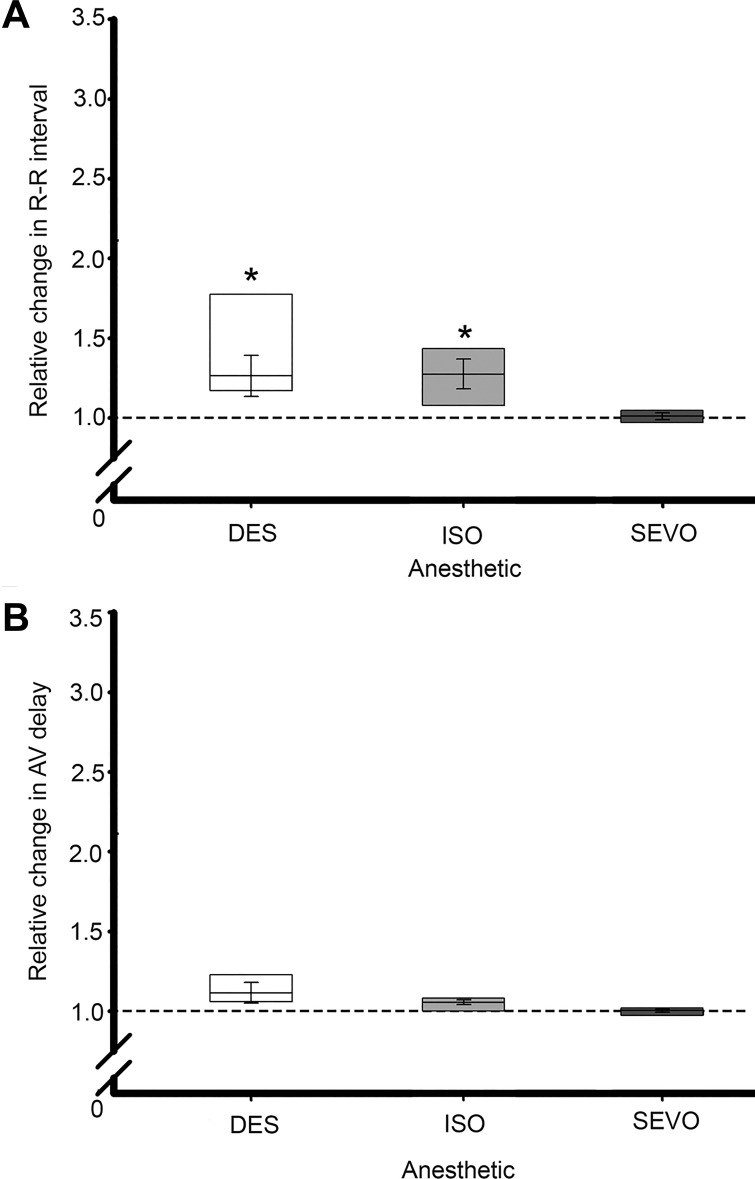

The HR effects of exposure to 1.0 MAC of a given anesthetic are summarized in Fig. 2. All anesthetics tested showed a tendency to increase R-R interval (slowed HR) starting at 5 min of exposure; at 15 min of exposure, these changes reached significance for all anesthetics. Although a general trend of increasing AVd with duration of exposure to anesthetics was observed, this did not reach significance at 15 min of exposure to DES and SEVO but was significant for ISO at this exposure time.

Fig. 2.

Time-dependent responses of the isolated zebrafish heart to anesthetics. A: mean interbeat (R-R) interval began to elongate within 1 min of anesthetic exposure to desflurane (DES), isoflurane (ISO), and sevoflurane (SEVO), showing a maximal and significant (*) response at 15 min exposure. B: atrioventricular delay (AVd) began to elongate within 1 min of anesthetic exposure to all anesthetics but only showed a significant difference from control during ISO exposure at 15 min duration. In this and in subsequent figures, horizontal dashed line indicates pretreatment HR and AVd; boxes represent data ranges; n = 6 for all groups; *P ≤ 0.05 vs. preexposure value. Differences shown here are analyzed by paired two-way ANOVA.

Concentration-dependent anesthetic effects on HR and AVd.

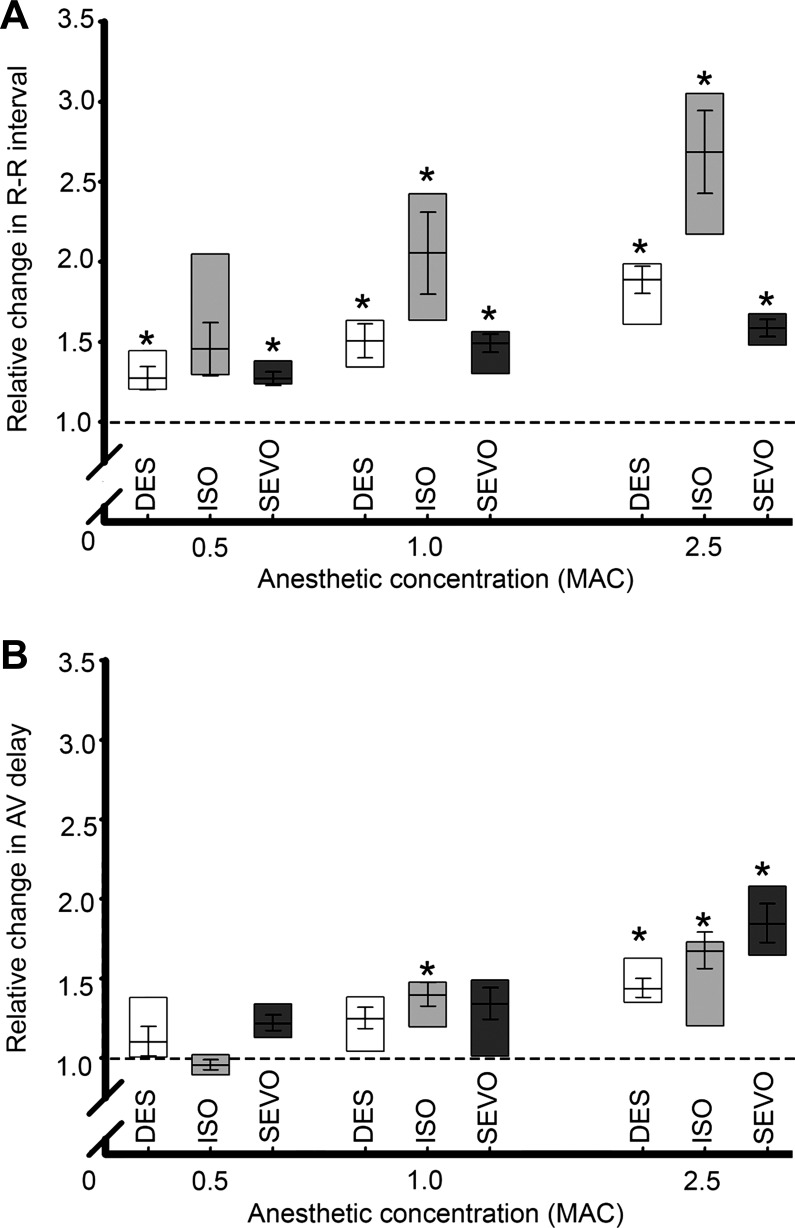

These results are summarized in Figs. 3 and 4. Significant bradycardia was observed during exposure to DES and SEVO at all concentrations tested. Exposure to ISO evoked significant changes in rate only at concentrations of 1.0 MAC and above (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Concentration-dependent responses of the isolated zebrafish heart to anesthetics relative to a 1.0 human minimum alveolar concentration (MAC; see text for details) as measured by patient monitor. A: chronotropic responses were observed beginning at 0.5 MAC and increased at higher concentrations. B: effects of altering anesthetic concentrations on atrioventricular delay. *Significant differences from control, analyzed by paired two-way ANOVA, P ≤ 0.05.

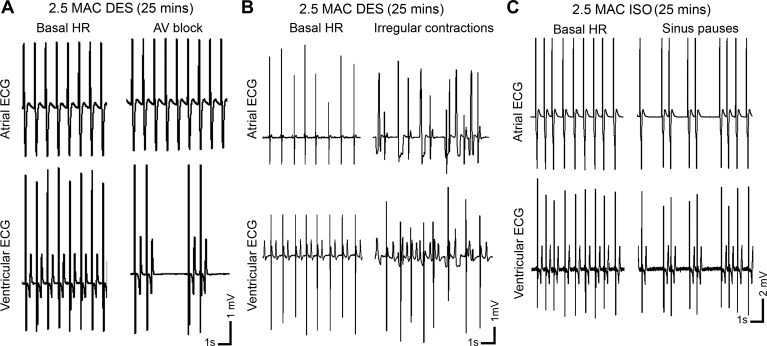

Fig. 4.

Representative ECG traces from arrhythmic periods occurring during exposure to high concentrations of inhalational anesthetics. Periods of atrioventricular block (A) or irregular, fibrillation-like contractions (B) were observed after 25 min of DES exposure, while sinus pauses (C) developed after 25 min of ISO exposure (anesthetic concentration 2.5 MAC).

None of the anesthetics significantly altered AVd at 0.5 MAC, while only ISO caused AVd to change significantly at 1.0 MAC. In contrast, all anesthetics caused AVd to increase significantly at 2.5 MAC (Fig. 3B).

At the highest dosage used in this study, all anesthetics caused arrhythmias during prolonged exposure. For instance, DES caused a fibrillation-like arrhythmia in two hearts exposed at 2.5 MAC for 25–30 min (example in Fig. 4A), while another heart developed a conduction block in which the relationship of atrial to ventricular contraction varied between 2:1 and 3:1 (Fig. 4B). In three of six hearts exposed to ISO, periods of irregular contraction or sinus pauses developed by 25 min of exposure at 2.5 MAC (see Fig. 4C).

Effects of autonomic blockade and VSN stimulation.

To investigate the contributions of neurally mediated and myocardial mechanisms involved in anesthetic-induced disruption of heart rate, isolated hearts were exposed to anesthetics during complete autonomic blockade with a combination of ATR (parasympatholytic) and TIM (sympatholytic); these effects are summarized in Fig. 5. In the presence of autonomic blockade, significant bradycardia was still observed after 15 min of exposure to DES and ISO, while there was no significant change in HR from control values during exposure to SEVO. There were no significant changes in AVd during autonomic blockade in combination with any anesthetic.

Fig. 5.

Effects of combined anesthetic exposure and autonomic blockade on HR and AVd. Hearts were exposed to a combination of atropine (200 μM; parasympatholytic) and timolol (100 μM; sympatholytic) to eliminate autonomic tone originating within intracardiac nervous system. A: during blockade significant (*P ≤ 0.05) elongation of R-R interval occurred during exposure to DES and ISO but not to SEVO. B: there were no significant anesthetic effects on AVd during autonomic blockade. Data were analyzed by paired Student’s t-test.

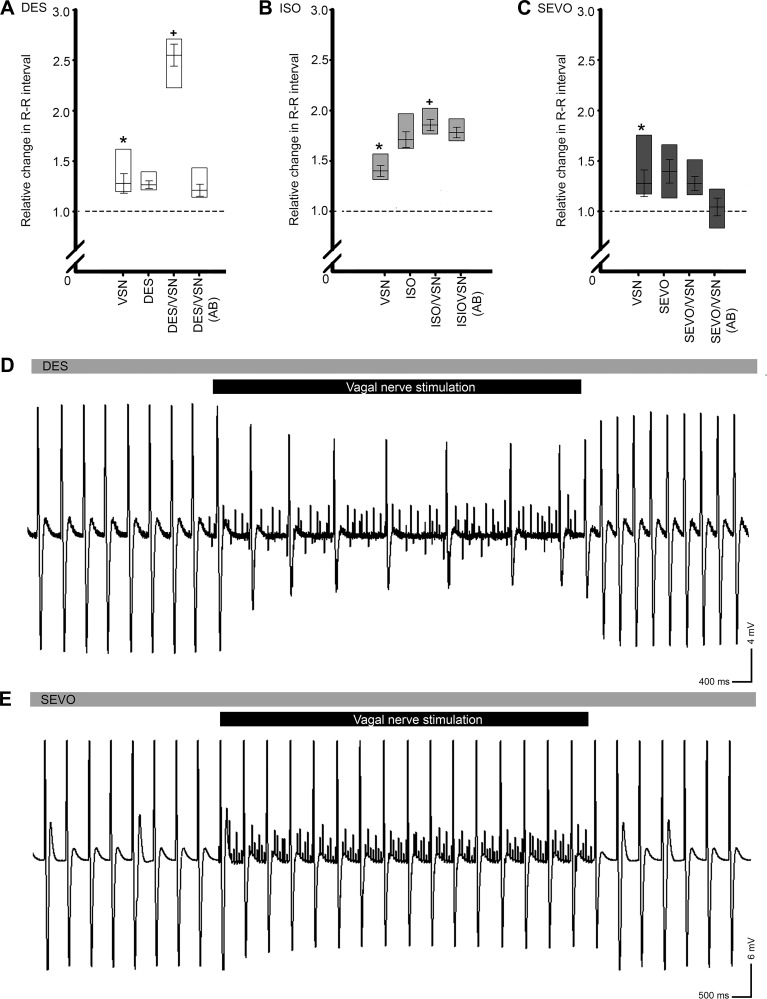

Stimulation of the VSN caused a significant elongation of R-R interval in the absence of anesthetic (Fig. 6, A–C and example ECG traces, Fig. 6, D and E). During exposure to DES (Fig. 6A) and ISO (Fig. 6B), repeated VSN stimulation resulted in a further elongation of R-R interval that was significantly greater than the change evoked by nerve stimulation alone. This effect was not observed during combined nerve stimulation and exposure to SEVO (Fig. 6, C and E). As a control for the efficacy of VSN stimulation in these experiments, cardiac nerve stimulation and anesthetic and autonomic blockade were combined. No chronotropic changes relative to control values were observed during VSN stimulation under these conditions for any anesthetic agent.

Fig. 6.

Effects of vagosympathetic nerve (VSN) stimulation on HR during anesthetic exposure. Isolated hearts were exposed to anesthetic or a combination of anesthetic and autonomic blockade to determine the involvement of the intracardiac autonomic nervous system. In all cases, preanesthetic VSN resulted in a significant elongation of the R-R interval (*significant difference, P ≤ 0.05, A–C). In the presence of DES (A) and ISO (B), the effects of VSN- and anesthetic-induced R-R elongation were summative. VSN-induced R-R elongation was prevented by SEVO (C). Data were analyzed by paired Student’s t-test. Representative atrial ECG traces showing responses to VSN during DES (D) and SEVO (E) exposure. Gray bars represent the continuous presence of vapor anesthetic in the bath, and black bars represent periods of VSN.

DISCUSSION

General anesthetics have been a mainstay of surgical practice for more than 150 years, but the mechanisms by which they mediate their clinical actions remain unclear (7). These agents often produce undesirable side effects, in particular, respiratory and cardiovascular depression, each of which involve unknown targets (25) and, thus, carry an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events (21, 49). Work on a wide variety of animal models for cardiovascular diseases has shown that the type and dosage of anesthetic that is used can have a major impact on cardiovascular function. The wide range of anesthetic and dosing regimes utilized in these studies have, thus, produced variable results, depending on the type of experimental intervention, study design, physiological differences between species and strains, and institutional regulations (31).

In the present study, we have established the viability of the isolated zebrafish heart as a novel model for the study of the chronotropic effects of vapor anesthetics. To date, the adoption of zebrafish into anesthetic research programs has been hampered by specific limitations. These include difficulties in determining the exact dose of anesthetic compound administered, uniformity in interpretation of results, and correlation of dosages that adversely affect the zebrafish heart with dosages causing cardiac effects in other species (6, 47). Here, we address the issue of the potential lack of anesthetic solubility in aqueous solutions; specifically, that the vapor-phase anesthetics used in the current study are considered to be insoluble in water. In this context, we found in preliminary experiments that concentrations of vapor anesthetics detected by a gas chromatograph-type patient monitor during experiments correlated well with anesthetic concentrations in the perfusate measured from offgassing of control samples. In addition, cardiac effects (such as changes in R-R period) were observed only when the anesthetic was vaporized into the perfusate delivered to the heart. This indicates that the observed changes were, in fact, the result of exposure of the isolated heart to the anesthetic agent, and not an artifact of the use of the vaporizer. While the exact form of the anesthetic agents in the perfusate was unknown, it is possible that these agents entered the aqueous phase as a result of “microbubbles” formed during passage of the gas through the vaporizer, eventually reaching the heart via the perfusate.

Effects of anesthetics on HR and AVd.

In previous studies in mammals, a variety of responses, including tachycardia (11–14, 37, 57, 60) and bradycardia (9, 31, 40, 44, 45), as well as stabilized HR (11, 24, 26, 36), have been described during exposure to inhalational anesthetics. The prevailing detrimental cardiac response in mammals is a depression of cardiac output, usually mediated by a slowing of the HR (23, 31). Such a variety of responses reinforces the need for a tractable model to better understand the factors involved in such effects. We have shown that the isolated zebrafish heart represents such a model.

In this study, the major effect of all anesthetics was to induce a general reduction in HR in the isolated zebrafish heart, occurring in a time- and dose-dependent manner similar to chronotropic effects described in mammalian hearts. At 1.0 MAC, DES, ISO, and SEVO all evoked significant elongation of the R-R interval by 15-min exposure. In contrast, the AVd responses were variable during exposure to the anesthetic agents, with only ISO evoking a significant increase in AVd after 15 min at 1.0 MAC. The reasons for this variability are not clear, but the relative lack of consistent effects of inhalational anesthetics on AVd in this study could have arisen because subtle changes in delay time may have been masked by an inherently high beat-to-beat variability observed in the zebrafish heart. Such an effect has been previously reported in studies on isolated hearts, investigating the effects of temperature (34) and autonomic agents (55). Furthermore, alterations in AVd are known to be involved in arrhythmogenesis, especially when there exist comorbidities (3, 16, 22). We also observed arrhythmogenic effects of anesthetics in the present study, but the potential contributions of changes in AVd to these arrhythmias remain obscure. This effect warrants further investigation to be properly understood.

In a previous study, it was found that ISO codelivered with tricaine resulted in a more stable and maintainable HR during recoverable anesthesia in intact adult zebrafish (27). The authors of this study proposed that this may have been due to a positive synergistic interaction between these agents on the heart, but the mechanisms involved were not determined, nor did these authors investigate the effects of ISO alone. Here, we report a significant bradycardic effect of ISO alone in isolated hearts. In contrast, tricaine anesthetic alone can have variable cardiovascular effects in zebrafish (7, 27). For instance, Chen et al. (7) showed that HR decreased during anesthesia of 4-day postfertilization larval zebrafish with 1 mM tricaine. In that study, replacement of tricaine solution with embryo medium without anesthetic resulted in recovery of HR to control values, although no timeline for this recovery was reported. In the current study, exposure of the isolated adult heart to tricaine alone resulted in a decrease in HR similar to that previously reported in larval zebrafish (7). Furthermore, we also found that recovery from tricaine effects occurred within minutes of switching the perfusate to fresh saline without tricaine. Therefore, we used a standardized acclimation period of 30 min postisolation, in which the heart was being superfused with fresh saline, to wash out tricaine remaining from the heart isolation procedure. Thus, the effects that we observed during exposure to DES, ISO, and SEVO in our study were likely to have been free of influences from residual tricaine.

Concentration-dependent effects.

The use of an anesthetic dose of 1.0 MAC in the present experiments represented an attempt to define a “clinically relevant” dosage at the level of the isolated tissue. However, in the clinical setting, the effective concentrations of inhalational anesthetics can vary greatly between individuals, or between induction of anesthesia and maintenance in the same individual. Thus, to investigate potential concentration effects, in our study, the anesthetic dose in the perfusate was varied from 0.5 to 2.5 MAC. R-R interval was significantly elongated by both DES and SEVO across this range of concentrations, while ISO was only effective at concentrations of 1.0 MAC and above. The latter finding was consistent with previous mammalian studies in which ISO concentrations greater than 1.0 MAC consistently evoked decreases in HR (see Ref. 44).

At 2.5 MAC, all vapors caused significant increases in AVd. This finding contrasts with previous reports showing that, under other physiological conditions [i.e., altered temperature (34) or ANS activation (55)], AVd was not affected. That AVd was elongated only at relatively high anesthetic concentrations in the present study suggests that the lack of effect on AVd at lower concentrations may have resulted from masking of AVd changes by a high interbeat variability in AVd. This possibility should be addressed in future experiments.

Arrhythmogenicity of vapor anesthetics.

In preliminary experiments, we found that prolonged exposure (≥25 min) to, or rapid step increases of >1% in concentration of, DES and ISO resulted in increased probability of arrhythmogenesis (see Fig. 4). In patients and experimental animals, DES has also been associated with periods of substantial sympathoexcitation and tachycardia when first introduced into the inspired gas after intravenous induction of anesthesia (13, 14, 60) or during periods of steady-state anesthesia when the inspired DES concentration is abruptly increased (14, 39, 57). ISO has also been shown to provoke a response that is qualitatively similar to that of DES when abruptly increased, but the magnitude of the response is far less (13, 57). Thus, the proarrhythmogenic effects of anesthetics reported in mammals (see Ref. 4) may parallel those seen in fish hearts in the present study, suggesting that this response may be conserved across the Vertebrata. One potential mechanism for this effect is anesthetic-induced modulation of conductance of depolarizing ion channels in the membranes of cardiac myocytes (29, 39, 61).

In contrast with the general arrhythmogenic effects of DES and ISO, the administration of SEVO in rapidly increasing inspired concentrations has not been associated clinically with such effects (11), nor did we observe evidence of arrhythmogenesis with this agent in the isolated zebrafish heart.

Effects of autonomic blockade and VSN stimulation.

Enhancement of inhibitory postsynaptic responses and inhibition of excitatory synaptic transmission are generally thought to be the predominant modes of action of general anesthetics in the CNS (59). Such disruption of central neural control elements, some of which modulate tonic sympathetic and parasympathetic outflow from the brain stem and spinal cord to the periphery, may also contribute to changes in cardiovascular regulation during anesthesia (44, 46). Given that many of the same receptors mediating anesthetic effects in the CNS are also present in the heart, it is not surprising that direct actions of anesthetics on the myocardium, independent of autonomic activity, have been demonstrated (4, 41, 50, 51, 58). However, vapor anesthetics likely also affect neurotransmission in the ANS, potentially contributing to alterations in cardiac function. We have established that the major hallmarks of autonomic innervation and the physiology of neural control of the zebrafish heart are analogous to those in humans (54, 55). The ICNS represents the final common pathway for neural control of cardiac function, and this system remains active in controlling the pacemaker in isolated hearts (55). Therefore, to differentiate neurally mediated effects from direct actions of anesthetics on the myocardium, we exposed hearts to a combination of muscarinic and β-adrenergic receptor antagonists, which blocked all effects of cholinergic and adrenergic drive to the myocardium arising from the ICNS.

Although all anesthetic agents evoked bradycardia in the current study, only that mediated by SEVO was prevented by autonomic blockade. This strongly suggests that the cardiac effect of this anesthetic was principally of neural origin in the isolated zebrafish heart. Many volatile anesthetics inhibit central neuronal nicotinic and muscle-type muscarinic ACh receptors, even at concentrations less than those sufficient for full anesthesia (19, 56, 59). However, neuronal muscarinic receptors are activated in the rat CNS during anesthesia (28). Thus, it may be that the inhibition of SEVO-mediated bradycardia during autonomic blockade resulted from the blunting of SEVO-induced activation of muscarinic neurotransmission in the ICNS. Such activation could have driven a muscarinically mediated decrease in pacemaker rate, which was then attenuated by ATR. Thus, we hypothesize that one mechanism of the influence of SEVO on the heart is through its actions on synaptic (particularly cholinergic) transmission within the ICNS.

In contrast to the effects of autonomic blockade on the cardiac response to SEVO, significant bradycardia was still observed with application of both DES and ISO during autonomic blockade. This suggests that the cardiac effects of these anesthetics were mainly the result of actions directly on cardiac pacemaker cells. This finding agrees with a previous report describing direct negative chronotropic effects of DES when ANS activity was depressed or abolished in the cat (53). In both zebrafish and mammals, hyperpolarization-activated, cyclic-nucleotide gated (HCN) channels are known to contribute a major portion of the diastolic depolarizing current in cardiac pacemaker cells (30, 35). HCN channels are inhibited by inhaled anesthetics through a hyperpolarizing shift in the voltage dependence of activation of these channels, resulting in a decrease in maximal available current, effectively blocking channel conductance over the typical subthreshold voltage range (8). Therefore, it is possible that such a mechanism may be operating in the bradycardic response of the isolated zebrafish heart to vapor anesthetics.

In addition to the effects of these anesthetics on the ICNS, the function of extrinsic autonomic inputs to the heart may also be modified. In humans, reflex heart rate responses and changes in sympathetic nerve activity during arterial pressure perturbations are diminished with exposure to SEVO at increasing concentrations. These clinical responses are generally similar to those produced by ISO and DES (12). Moreover, previous reports have described alterations in sympathetic and parasympathetic cardiac nerve traffic during periods of anesthesia, which may have contributed to chronotropic effects of these anesthetics (32). In the isolated zebrafish heart, we tested the effects of simulating input from the CNS to the ICNS by stimulating the VSN trunks attached to isolated hearts during exposure to anesthetic. During exposure to DES and ISO, VSN stimulation enhanced bradycardia, an effect that was summative with the anesthetic effect on HR. These results support the hypothesis that DES and ISO were acting directly on myocardial targets, and were not neurally mediated. This finding stands in contrast with a previous report that ISO attenuated chronotropic responses in a dose-dependent fashion during CNS autonomic stimulation in a feline model (44). It is not clear how this work correlates with our results. On the other hand, VSN stimulation during exposure to SEVO in the zebrafish heart had no additional chronotropic effect. One possible explanation is that neurotransmission within the ICNS is depressed by this agent. This finding parallels the results of the experiments combining autonomic blockade with SEVO, further indicating that the chronotropic effects of SEVO were neurally mediated.

Perspectives and Significance

There is now ample evidence that clinical concentrations of most general anesthetics, particularly volatile anesthetics, have interactions with multiple targets in the body (25), and that some of these interactions can drastically alter normal cardiac function (29). Though studies performed on isolated cardiomyocytes have produced valuable insights into the side effects of anesthetics at the molecular and cellular level (see Ref. 29), interactions and effects at the level of the organ may differ. The results of the present study imply that there are likely both direct and neurally mediated effects of vapor anesthetics on cardiac chronotropy. From the current study, it appears most likely that no single intracardiac element is fully responsible for the chronotropic changes observed during anesthesia, and that in all probability, the observed effects are the result of multiple interacting neural and myocardial mechanisms. Although the use of the isolated zebrafish heart may represent an oversimplification in terms of addressing the broadly integrated mechanisms underlying anesthetic side effects during surgery in humans, we argue that a major strength of our model is that all noncardiac factors are eliminated, focusing on effects of intracardiac origin. Our findings allow for the development of studies to identify and investigate cardiac-specific mechanisms involved in the cardiotropic consequences of anesthesia. Determining how and why commonly used anesthetics cause a drop in HR and, thus, in cardiac output, will provide insight into the improvement of such anesthetics and the development of new ones that reduce or eliminate these effects.

GRANTS

The Natural Sciences and Engineering Council (NSERC) of Canada supported this work through a Discovery Grant to R. P. Croll (Grant 327140). M. R. Stoyek was a recipient of a NSERC Post-Graduate Research Scholarship. The Dalhousie University Faculty of Medicine Research Fund (to F. M. Smith) and Abbott Canada (to M. K. Schmidt) also provided partial support for this work.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.R.S., M.K.S., F.M.W., R.P.C., and F.M.S. conceived and designed research; M.R.S. performed experiments; M.R.S. analyzed data; M.R.S., M.K.S., F.M.W., R.P.C., and F.M.S. interpreted results of experiments; M.R.S. prepared figures; M.R.S. drafted manuscript; M.R.S., M.K.S., F.M.W., R.P.C., and F.M.S. edited and revised manuscript; M.R.S., M.K.S., F.M.W., R.P.C., and F.M.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Sevoflurane was generously provided by Abbott Canada to M. K. Schmidt.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angelotti T. Anesthetic pharmacology of the autonomic nervous system. In: Neuroscientific Foundations of Anesthesiology, edited by Mashour GA and Lydic R. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2011, p. 186–201. doi: 10.1093/med/9780195398243.003.0096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armour JA. Potential clinical relevance of the “little brain” on the mammalian heart. Exp Physiol 93: 165–176, 2008. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.041178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auricchio A, Stellbrink C, Block M, Sack S, Vogt J, Bakker P, Klein H, Kramer A, Ding J, Salo R, Tockman B, Pochet T, Spinelli J; The Pacing Therapies for Congestive Heart Failure Study Group. The Guidant Congestive Heart Failure Research Group . Effect of pacing chamber and atrioventricular delay on acute systolic function of paced patients with congestive heart failure. Circulation 99: 2993–3001, 1999. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.99.23.2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aypar E, Karagoz AH, Ozer S, Celiker A, Ocal T. The effects of sevoflurane and desflurane anesthesia on QTc interval and cardiac rhythm in children. Paediatr Anaesth 17: 563–567, 2007. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2006.02152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chamberlain DA, Leinbach RC, Sanders CA. The effect of paired atrial pacing on left atrial and ventricular performance in the dog. Cardiovasc Res 4: 116–126, 1970. doi: 10.1093/cvr/4.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaudhari GH, Chennubhotla KS, Chatti K, Kulkarni P. Optimization of the adult zebrafish ECG method for assessment of drug-induced QTc prolongation. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 67: 115–120, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen H, Chan JY, Li S, Liu JJ, Wyman IW, Lee SM, Macartney DH, Wang R. In vivo reversal of general anesthesia by cucurbit[7]uril with zebrafish models. RSC Advances 5: 63745–63752, 2015. doi: 10.1039/C5RA09406B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen X, Sirois JE, Lei Q, Talley EM, Lynch C III, Bayliss DA. HCN subunit-specific and cAMP-modulated effects of anesthetics on neuronal pacemaker currents. J Neurosci 25: 5803–5814, 2005. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1153-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Constantinides C, Mean R, Janssen BJ. Effects of isoflurane anesthesia on the cardiovascular function of the C57BL/6 mouse. ILAR J 52: e21–e31, 2011. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dershwitz M, Rosow C. Pharmacology of intravenous anaesthetics. In: Anesthesiology, edited by Longnecker DE, Brown DL, Newman M, Zapol W. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008, p. 849–868. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ebert TJ, Harkin CP, Muzi M. Cardiovascular responses to sevoflurane: a review. Anesth Analg 81, Suppl: 11S–22 S, 1995. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199512001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebert TJ, Muzi M, Lopatka CW. Neurocirculatory responses to sevoflurane in humans. A comparison to desflurane. Anesthesiology 83: 88–95, 1995. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199507000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ebert TJ, Muzi M. Sympathetic activation with desflurane in humans. Adv Pharmacol 31: 369–378, 1994. doi: 10.1016/S1054-3589(08)60629-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebert TJ, Muzi M. Sympathetic hyperactivity during desflurane anesthesia in healthy volunteers. A comparison with isoflurane. Anesthesiology 79: 444–453, 1993. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199309000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eger EI II, Saidman LJ, Brandstater B. Minimum alveolar anesthetic concentration: a standard of anesthetic potency. Anesthesiology 26: 756–763, 1965. doi: 10.1097/00000542-196511000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Sherif N, Hope RR, Scherlag BJ, Lazzara R. Re-entrant ventricular arrhythmias in the late myocardial infarction period. 2. Patterns of initiation and termination of re-entry. Circulation 55: 702–719, 1977. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.55.5.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fish RE, Brown ME, Danneman PJ, Karas AZ (Editors). Anesthesia and Analgesia in Laboratory Animals (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flecknell PA. Anaesthesia of common laboratory species: special considerations. In: Laboratory Animal Anaesthesia (3rd ed.), edited by Flecknell PA. London: Academic, 2009, p. 181–241. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-369376-1.00006-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flood P, Ramirez-Latorre J, Role L. α4 β2 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the central nervous system are inhibited by isoflurane and propofol, but α7-type nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are unaffected. Anesthesiology 86: 859–865, 1997. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199704000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forman SA, Mashour GA. Pharmacology of inhalational anaesthetics. In: Anesthesiology, edited by Longnecker DE. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008, p. 739–766. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fowler MA, Spiess BD. Post-anesthesia recovery. In: Clinical Anesthesia (6th ed.), edited by Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, Cahalan MK, Stock MC. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, 2009, p. 1423–1439. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldreyer BN, Damato AN. The essential role of atrioventricular conduction delay in the initiation of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. Circulation 43: 679–687, 1971. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.43.5.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanley PJ, Ray J, Brandt U, Daut J. Halothane, isoflurane and sevoflurane inhibit NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) of cardiac mitochondria. J Physiol 544: 687–693, 2002. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.025015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harkin CP, Pagel PS, Kersten JR, Hettrick DA, Warltier DC. Direct negative inotropic and lusitropic effects of sevoflurane. Anesthesiology 81: 156–167, 1994. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199407000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hemmings HC Jr, Akabas MH, Goldstein PA, Trudell JR, Orser BA, Harrison NL. Emerging molecular mechanisms of general anesthetic action. Trends Pharmacol Sci 26: 503–510, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holaday DA, Smith FR. Clinical characteristics and biotransformation of sevoflurane in healthy human volunteers. Anesthesiology 54: 100–106, 1981. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198102000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang WC, Hsieh YS, Chen IH, Wang CH, Chang HW, Yang CC, Ku TH, Yeh SR, Chuang YJ. Combined use of MS-222 (tricaine) and isoflurane extends anesthesia time and minimizes cardiac rhythm side effects in adult zebrafish. Zebrafish 7: 297–304, 2010. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2010.0653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hudetz AG, Wood JD, Kampine JP. Cholinergic reversal of isoflurane anesthesia in rats as measured by cross-approximate entropy of the electroencephalogram. Anesthesiology 99: 1125–1131, 2003. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200311000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hüneke R, Fassl J, Rossaint R, Lückhoff A. Effects of volatile anesthetics on cardiac ion channels. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 48: 547–561, 2004. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-5172.2004.00391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Irisawa H. Comparative physiology of the cardiac pacemaker mechanism. Physiol Rev 58: 461–498, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janssen BJ, De Celle T, Debets JJ, Brouns AE, Callahan MF, Smith TL. Effects of anesthetics on systemic hemodynamics in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H1618–H1624, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01192.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurosawa M, Meguro K, Nagayama T, Sato A. Effects of sevoflurane on autonomic nerve activities controlling cardiovascular functions in rats. J Anesth 3: 109–117, 1989. doi: 10.1007/s0054090030109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li N, Csepe TA, Hansen BJ, Dobrzynski H, Higgins RS, Kilic A, Mohler PJ, Janssen PM, Rosen MR, Biesiadecki BJ, Fedorov VV. Molecular mapping of sinoatrial node HCN channel expression in the human heart. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 8: 1219–1227, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.115.003070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin E, Ribeiro A, Ding W, Hove-Madsen L, Sarunic MV, Beg MF, Tibbits GF. Optical mapping of the electrical activity of isolated adult zebrafish hearts: acute effects of temperature. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 306: R823–R836, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00002.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mangoni ME, Nargeot J. Genesis and regulation of the heart automaticity. Physiol Rev 88: 919–982, 2008. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manohar M, Parks CM. Porcine systemic and regional organ blood flow during 1.0 and 1.5 minimum alveolar concentrations of sevoflurane anesthesia without and with 50% nitrous oxide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 231: 640–648, 1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marano G, Grigioni M, Tiburzi F, Vergari A, Zanghi F. Effects of isoflurane on cardiovascular system and sympathovagal balance in New Zealand white rabbits. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 28: 513–518, 1996. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199610000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mashour GA, Lydic R (Editors). Neuroscientific Foundations of Anesthesiology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University, 2011. doi: 10.1093/med/9780195398243.001.0001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore MA, Weiskopf RB, Eger EI II, Noorani M, McKay L, Damask M. Rapid 1% increases of end-tidal desflurane concentration to greater than 5% transiently increase heart rate and blood pressure in humans. Anesthesiology 81: 94–98, 1994. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199407000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park KS, Kong ID, Park KC, Lee JW. Fluoxetine inhibits L-type Ca2+ and transient outward K+ currents in rat ventricular myocytes. Yonsei Med J 40: 144–151, 1999. doi: 10.3349/ymj.1999.40.2.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pauza DH, Rysevaite K, Inokaitis H, Jokubauskas M, Pauza AG, Brack KE, Pauziene N. Innervation of sinoatrial nodal cardiomyocytes in mouse. A combined approach using immunofluorescent and electron microscopy. J Mol Cell Cardiol 75: 188–197, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pauza DH, Saburkina I, Rysevaite K, Inokaitis H, Jokubauskas M, Jalife J, Pauziene N. Neuroanatomy of the murine cardiac conduction system: a combined stereomicroscopic and fluorescence immunohistochemical study. Auton Neurosci 176: 32–47, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pauza DH, Skripka V, Pauziene N, Stropus R. Morphology, distribution, and variability of the epicardiac neural ganglionated subplexuses in the human heart. Anat Rec 259: 353–382, 2000. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poterack KA, Kampine JP, Schmeling WT. Effects of isoflurane, midazolam, and etomidate on cardiovascular responses to stimulation of central nervous system pressor sites in chronically instrumented cats. Anesth Analg 73: 64–75, 1991. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199107000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Preckel B, Schlack W, Comfère T, Obal D, Barthel H, Thämer V. Effects of enflurane, isoflurane, sevoflurane and desflurane on reperfusion injury after regional myocardial ischaemia in the rabbit heart in vivo. Br J Anaesth 81: 905–912, 1998. doi: 10.1093/bja/81.6.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Price HL, Linde HW, Morse HT. Central nervous actions of halothane affecting the systemic circulation. Anesthesiology 24: 770–778, 1963. doi: 10.1097/00000542-196311000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Renier C, Faraco JH, Bourgin P, Motley T, Bonaventure P, Rosa F, Mignot E. Genomic and functional conservation of sedative-hypnotic targets in the zebrafish. Pharmacogenet Genomics 17: 237–253, 2007. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3280119d62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robinson EA, Rhee KS, Doytchinova A, Kumar M, Shelton R, Jiang Z, Kamp NJ, Adams D, Wagner D, Shen C, Chen LS, Everett TH, Fishbein MC, Lin SF, Chen PS. Estimating sympathetic tone by recording subcutaneous nerve activity in ambulatory dogs. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 26: 70–78, 2015. doi: 10.1111/jce.12508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ross LG, Ross B. Anesthetic and Sedative Techniques for Aquatic Animals (3rd ed.). Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saarnivaara L, Lindgren L. Prolongation of QT interval during induction of anaesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 27: 126–130, 1983. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1983.tb01921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seagard JL, Bosnjak ZJ, Hopp FA, Kotrly KJ, Ebert TJ, Kampine JP. Cardiovascular effects of general anesthesia. In: Effects of Anesthesia, edited by Covino BG, Fozzard HA, Rehder K, Strichartz G. Philadelphia, PA: Williams and Wilkins, 1985, p. 149–177. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sear JW. Perioperative control of hypertension: when will it adversely affect perioperative outcome? Curr Hypertens Rep 10: 480–487, 2008. doi: 10.1007/s11906-008-0090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Skovsted P, Sapthavichaikul S. The effects of isoflurane on arterial pressure, pulse rate, autonomic nervous activity, and barostatic reflexes. Can Anaesth Soc J 24: 304–314, 1977. doi: 10.1007/BF03005103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stoyek MR, Croll RP, Smith FM. Intrinsic and extrinsic innervation of the heart in zebrafish (Danio rerio). J Comp Neurol 523: 1683–1700, 2015. doi: 10.1002/cne.23764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stoyek MR, Quinn TA, Croll RP, Smith FM. Zebrafish heart as a model to study the integrative autonomic control of pacemaker function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 311: H676–H688, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00330.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Violet JM, Downie DL, Nakisa RC, Lieb WR, Franks NP. Differential sensitivities of mammalian neuronal and muscle nicotinic acetylcholine receptors to general anesthetics. Anesthesiology 86: 866–874, 1997. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199704000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weiskopf RB, Moore MA, Eger EI II, Noorani M, McKay L, Chortkoff B, Hart PS, Damask M. Rapid increase in desflurane concentration is associated with greater transient cardiovascular stimulation than with rapid increase in isoflurane concentration in humans. Anesthesiology 80: 1035–1045, 1994. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199405000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wig J, Bali IM, Singh RG, Kataria RN, Khattri HN. Prolonged Q-T interval syndrome. Sudden cardiac arrest during anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 34: 37–40, 1979. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1979.tb04864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yamashita M, Mori T, Nagata K, Yeh JZ, Narahashi T. Isoflurane modulation of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed in human embryonic kidney cells. Anesthesiology 102: 76–84, 2005. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200501000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yli-Hankala A, Randell T, Seppälä T, Lindgren L. Increases in hemodynamic variables and catecholamine levels after rapid increase in isoflurane concentration. Anesthesiology 78: 266–271, 1993. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199302000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou C, Liu J, Chen XD. General anesthesia mediated by effects on ion channels. World J Crit Care Med 1: 80–93, 2012. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v1.i3.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]