Abstract

Growing evidence suggests that versican is important in the innate immune response to lung infection. Our goal was to understand the regulation of macrophage-derived versican and the role it plays in innate immunity. We first defined the signaling events that regulate versican expression, using bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) from mice lacking specific Toll-like receptors (TLRs), TLR adaptor molecules, or the type I interferon receptor (IFNAR1). We show that LPS and polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid [poly(I:C)] trigger a signaling cascade involving TLR3 or TLR4, the Trif adaptor, type I interferons, and IFNAR1, leading to increased expression of versican by macrophages and implicating versican as an interferon-stimulated gene. The signaling events regulating versican are distinct from those for hyaluronan synthase 1 (HAS1) and syndecan-4 in macrophages. HAS1 expression requires TLR2 and MyD88. Syndecan-4 requires TLR2, TLR3, or TLR4 and both MyD88 and Trif. Neither HAS1 nor syndecan-4 is dependent on type I interferons. The importance of macrophage-derived versican in lungs was determined with LysM/Vcan−/− mice. These studies show increased recovery of inflammatory cells in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of poly(I:C)-treated LysM/Vcan−/− mice compared with control mice. IFN-β and IL-10, two important anti-inflammatory molecules, are significantly decreased in both poly(I:C)-treated BMDMs from LysM/Vcan−/− mice and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from poly(I:C)-treated LysM/Vcan−/− mice compared with control mice. In short, type I interferon signaling regulates versican expression, and versican is necessary for type I interferon production. These findings suggest that macrophage-derived versican is an immunomodulatory molecule with anti-inflammatory properties in acute pulmonary inflammation.

Keywords: versican, syndecan-4; hyaluronan synthase 1; type I interferons; inflammation

INTRODUCTION

Versican, a chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan (CSPG), is abundantly expressed during lung development but expressed at very low levels in lungs of healthy adult mice, sheep, and humans (11, 25, 70). Recent work shows that versican is reexpressed and accumulates in the lungs of mice in disease models of gram-negative lung infection (16, 70), acute lung injury (84), asthma (64), pulmonary fibrosis (71), cancer (41, 79), and emphysema. In humans, versican accumulates in lung diseases such as pulmonary fibrosis (11), acute respiratory distress syndrome (11, 52), asthma (7, 33, 80), lymphangioleiomyomatosis (48), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (5, 47). Versican is also thought to be a central component of lung tumors and cancer (42, 65, 66). These studies show that the reexpression and accumulation of versican in lungs is a common observation in lung disease. While little is known about the factors that regulate versican expression or the role of versican in the pathogenesis of lung disease, accumulating evidence indicates that versican is a component of the immune response. Interactions between versican and other extracellular matrix molecules facilitate extravasation of immune cells from the circulation into sites of inflammation. Interactions with cell surface receptors [e.g., CD44 and Toll-like receptor (TLR)2] provide intrinsic signals that influence immune and inflammatory cell phenotype, impacting cell adhesion, migration, activation, and retention. Versican also serves as a reservoir for cytokines and growth factors, controlling their release and thus establishing fine control over cell activity and behavior (82).

To date, the only known signaling pathway regulating versican promoter activity is the canonical Wnt/β-catenin/T cell factor (TCF) pathway, which Rahmani and colleagues first described in airway smooth muscle cells (61–63). This was extended by Baarsma et al., who showed that transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1/β-catenin/TCF/lymphoid enhancer factor (LEF)-dependent gene expression was responsible for the increased expression of versican in smooth muscle cells treated with TGF-β1 (9, 10). The signaling pathway(s) responsible for the increased expression of versican in macrophages in response to gram-negative bacteria or viral infections has not been explored. Whether or not these different forms of infection, which signal through pattern recognition receptors such as TLR3 and TLR4, activate similar or different pathways to promote versican synthesis in macrophages also is not known.

Our recently published study raises the possibility of a novel alternative signaling pathway regulating versican gene transcription through TLR4 in lungs of mice exposed to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (16). A series of cell surface proteins, including CD14, MD-2, and TLR4, are responsible for the activation of cells exposed to LPS (2, 20, 32, 38, 53, 59). Engagement of TLR4 activates two distinct intracellular signaling pathways involving the adaptor molecules MyD88-toll-interleukin-1 receptor domain-containing adaptor protein (TIRAP) and TIR domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β (TRIF)-related adapter molecule 2 (TRAM), which in turn regulate signal transduction (1, 3, 31, 36). Signaling through MyD88 promotes the initial inflammatory response to LPS, resulting in increased expression of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 (1). In contrast, signaling through Trif is considered to be important to host defenses against viral, bacterial, fungal, and parasitic pathogens and able to promote resolution of inflammation via the expression of type I interferons (IFNs) (6, 27, 43, 77). Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3-kinase) has a role in TLR4 signaling, as it is involved in the release of TLR4 from the TIRAP-MyD88 adaptor complex and transition to the TRAM-TRIF-dependent phase of TLR4 signaling, which occurs in the endosome (3). The signaling pathway(s) downstream of TLR4 that regulates the versican promoter is not known. Studies show that versican expression and accumulation is rapidly increased in lungs of mice with gram-negative pneumonia, in whole lungs after oropharyngeal treatment with LPS or polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid [poly(I:C)], and in alveolar macrophages and bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) treated with LPS in vitro (16, 37). These studies suggest an important role for versican in the innate immune response to lung infection (16, 70).

Versican is a highly interactive molecule because of the charged nature of its glycosaminoglycan (GAG) side chains. Versican exists in at least four different isoforms due to alternative splicing of the major exons that code for attachment of the GAG side chains, chondroitin sulfate (CS), to the α- and β-GAG domains of the core protein (81, 87). Versican has multiple binding domains located on its core protein and associated CS side chains that are known to interact with factors important to the innate immune response including hyaluronan (22, 45), TLR2 (42, 75), cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, and growth factors (26, 82, 83). The ability of versican to bind to chemokines is due in large part to the negatively charged CS side chains associated with the α- and β-GAG domains. For example, versican regulates the availability and activity of several chemokines including CXCL2, CXCL10, CCL2, CCL5, CCL8, CCL20, and CCL21 (29, 40, 46, 83). Recent work in the cancer literature shows that versican is responsible for the reprogramming of dendritic cells to an immunosuppressive phenotype in a TLR2-dependent manner (75). In addition, versican is a component of the umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell glycocalyx, which has unique immunosuppressive properties enabling evasion of host rejection (19).

Thus the goals of the work described in this article were twofold. The first goal was to define the signaling pathways responsible for the increased expression of versican in macrophages. For these studies the TLR4 agonist LPS and the TLR3/Trif agonist poly(I:C) were used as molecular tools to precisely dissect the signaling pathways regulating versican expression in macrophages. We compared the signaling events leading to versican expression to those for syndecan-4 and hyaluronan synthase 1 (HAS1), both of which participate in the inflammatory response (16, 57, 64). Syndecan-4 is a heparan sulfate proteoglycan that was shown to be selectively and strikingly upregulated in a MyD88-dependent manner in lungs of mice exposed to Escherichia coli LPS and live E. coli (76). This provided a positive control for MyD88-dependent signaling. HAS1 is an isoform of hyaluronan synthase that produces hyaluronan, a GAG that is an important binding partner for versican (15, 22, 49, 57, 60). Among the HAS isoforms, HAS1 is selectively upregulated in lungs and macrophages of mice exposed to E. coli LPS and live E. coli (16). The mechanisms regulating HAS1 expression downstream of TLR4 are not known. The second goal was to identify the role of the versican-enriched extracellular matrix formed by macrophages in lungs in response to these signaling events. A major hurdle in defining a biological function for versican is that the lack of this CSPG is embryonically lethal (51) and a viable conditional knockout of the versican gene (Vcan) has not been available until recently (37). Therefore, we developed novel genetically engineered mice with conditional versican deficiency. LysM/Vcan−/− mice lack versican in cells expressing Cre-recombinase under control of the Lysozyme 2 promoter, which includes macrophages (35). Our findings show that versican expression in macrophages treated with LPS or poly(I:C) requires the TLR/Trif/type I IFN signaling pathway and that the versican-enriched matrix formed by macrophages in the lungs of mice treated with poly(I:C) is anti-inflammatory.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

LPS from E. coli serotype 0111:B4 was purchased from List Biological Laboratories (Campbell, CA). Ultrapure LPS (LPSEB) from E. coli serotype 0111:B4, poly(I:C), Pam3CSK4, and LY294002 were from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA). IC87114 was from Cayman (Ann Arbor, MI). IFN-α and IFN-β were from PBL Interferon Source (Piscataway, NJ). IFN-γ was from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ). Lithium chloride was from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). ICG001 was from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA). Murine recombinant Wnt3a, XAV939, CHIR99021, and monoclonal anti-LEF1 antibody were generous gifts of Dr. Jason Berndt (Seattle, WA). The polyclonal rabbit anti-versican antibody (β-GAG) was from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA), and the monoclonal rat anti-IFN-α and -β antibodies were from PBL Interferon Source. Gene-specific TaqMan primer-probe mixes used for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of versican (ThermoFisher Assay ID Mm01283063_m1), Has1 (Mm00468496_m1), syndecan-4 (Mm00488527_m1), IFN-β (Mm00439552_s1), CXCL1 (KC) (Mm04207460_m1), CXCL2 (MIP-2) (Mm00436450_m1), CCL2 (MCP-1) (Mm00441242_m1), TNF-α (Mm00443258_m1), IL-6 (Mm00446190_m1), IL-10 (Mm00439614_m1), and 18S (Hs99999901_s1) mRNA were from ThermoFisher Scientific (Grand Island, NY). For detection of versican, the primer-probe mix spanned the exon 3–4 junction. Cytokine and chemokine ELISA kits were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) and PBL Assay Science (Piscataway, NJ).

Mice.

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Washington (UW) approved all experiments. C57BL/6, TLR2−/−, TLR4−/−, MyD88−/−, and Ticam1Lps2 (Trifmutant) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Ifnar1−/− mice were a generous gift of Dr. Michael Gale (UW, Seattle, WA). All mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free animal facility until the day of the experiment. The room temperature was held in a range of 68–79°F, with the goal of 72°F and an acceptable temperature variation of no more than 4°F over a 24-h period. The acceptable room humidity range was 30–70%. Room lighting was programmed for 14 h of light and 10 h of dark. Mice were housed in HEPA-filtered ventilated shoe box cages (Allentown), and the ventilation in the animal housing room was at least 10–15 fresh air changes per hour per room. All mice were provided environmental enrichment and fed rodent diet ad libitum and had free access to fresh water at all times. Daily health checks were performed by the UW husbandry staff, who are overseen by laboratory animal veterinarians.

Development of LysM/Vcan−/− mice.

A floxed versican (Vcan) transgenic mouse was created with a targeted mutation of the Vcan gene. Vcantm1.1Cwf mice were generated by using a targeting vector to insert loxP sites in introns 3 and 4, as previously described (37). The Vcantm1.1Cwf (wild-type control, WT) mice were then bred to B6.129P2-Lyz2tm1(Cre)Ifo/J mice, resulting in B6.Vcanfl/fl/LysMCre+/0 mice that are homozygous at the Vcanfl/fl allele and heterozygous at the Lyz2-Cre allele (LysM+/0/Vcan−/−) or B6.Vcanfl/fl/LysMCre+/+ mice that are homozygous at both the Vcanfl/fl and Lyz2-Cre alleles (LysM/Vcan−/−) (17, 35). This allows Cre recombinase-mediated deletion of Vcan exon 4, resulting in a frame shift that causes a STOP codon near the beginning of exon 5 and thus mice that lack versican expression in myeloid cells. Cre recombinase was identified with primers (CCCAGAAATGCCAGATTACG, for the absence of Cre; CTTGGGCTGCCAGAATTTCTC, common for presence or absence of Cre; TTACAGTCGGCCAGGCTGAC, for the presence of Cre) from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). The versican gene was identified with a TaqMan primer-probe mix that spanned the exon 3–4 junction from Applied Biosciences (Foster City, CA).

Administration of poly(I:C) to mice.

With methods described previously, the oropharyngeal instillation of poly(I:C) (50 μg/mouse) or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was performed in 9- to 12-wk-old mice anesthetized with 3–4% isoflurane (16). After instillation, mice were allowed to recover and then returned to their cages, where they were allowed access to food and water for the remainder of the study. Mice were euthanized with an excess of isoflurane anesthesia followed by exsanguination. Whole blood was obtained by direct puncture, and the plasma was collected and stored at −70°C until use. Female and male mice were equally distributed among the groups. All studies were approved by the UW Office of Animal Welfare and IACUC.

Bronchoalveolar lavage.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed with 0.9% NaCl containing 0.6 mM EDTA. Four lavages of 1.0 ml each were performed. Lavage fluids were stored in individual aliquots with protease inhibitors (Pierce, Rockford, IL) at −80°C for later evaluation of cytokine and protein levels. BAL fluid cells were diluted with an acridine orange-propidium iodide dye solution to determine viability and total cell counts on a Nexcelom Cellometer (Nexcelom, Lawrence, MA). Cytocentrifuge preparations of BAL fluid cells were prepared and stained with Diff-Quik (American Scientific Products, McGaw Park, IL). A minimum of 200 cells were counted to evaluate mononuclear and polymorphonuclear differential cell counts.

Isolation of RNA from lung tissue and quantitative real-time PCR.

After lavage, the thoracic cavity was opened by a midline incision and the lungs were removed and placed into RNAlater (Ambion, Austin, TX) and stored at 4°C overnight for the extraction of RNA. Total RNA was isolated from lung tissue with the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA was reverse transcribed with the High-Capacity cDNA Archive Kit (Applied Biosystems) at 25°C for 10 min, at 37°C for 2 h, and at 90°C for 5 min. The resulting cDNA was used for standard PCR and quantitative real-time PCR. Real-time PCR was performed with an ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detector (Applied Biosystems) to quantify the mRNA expression of versican, syndecan-4, HAS1, CXCL1 (KC), CXCL2 (MIP-2), CCL2 (MCP-1), TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, and 18S. Real-time PCR was carried out in a total volume of 25 μl with a master mixture including all reagents required for PCR and gene-specific TaqMan primer-probe mixes. Cycle parameters were 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. The threshold cycle was calculated as the difference in threshold cycles for the target genes and 18S, and the relative mRNA expression was expressed as fold increase over the values obtained from RNA collected from untreated mice (i.e., normal lungs) of the appropriate genotype.

In vitro cell culture studies.

BMDMs and neutrophils were isolated from femurs and tibia of mice. For macrophages, bone marrow cells were cultured in “macrophage medium” (RPMI 1640, 10% FCS, 30% L929 cell supernatant, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin) (76). After 24 h, nonadherent cells were placed in macrophage medium for 6 days. Macrophages were then replated in macrophage medium in six-well tissue culture dishes at a density of 1–2 × 106 cells/well for 24 h before treatment in RPMI containing 10% FBS for up to 48 h. For neutrophils, after lysis of red blood cells bone marrow cells in 20 mM NaHEPES with 0.5% FCS (pH 7.4) were layered over 62% Percoll and centrifuged at 1,000 g for 30 min. Immature cells and nongranulocytic cells were discarded, and the neutrophil pellet was collected and washed in RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS. Purity was >98% as assessed by cytospins and cell differentials. Murine alveolar macrophages were harvested by BAL with PBS and cultured for 24 h in macrophage medium before stimulation. For lung fibroblasts, lung tissue was minced and digested with collagenase type I (1 mg/ml in DMEM with 5% FCS for 1 h at 37°C) and then pushed through a 22-gauge needle. Red blood cells were lysed, and the mixture was passed through a cell strainer. Cells were washed, plated in DMEM with 20% FCS, and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 and medium was changed daily until confluence (14).

Cytokine and chemokine ELISAs.

The concentrations of CXCL1 (KC), CXCL2 (MIP-2), CCL2 (MCP-1), TNF-α, TGF-β, IL-6, and IL-10 in tissue culture media, cells, and BAL fluids were measured with DuoSet ELISA development kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. IFN-β was measured with the VeriKine ELISA kit (PBL Assay Science).

Isolation of RNA from cell cultures and quantitative real-time PCR.

Total RNA was obtained from cell culture monolayers with either RNeasy Plus Mini or Rneasy Plus Micro Kits (Qiagen). cDNA was prepared and evaluated as described in Isolation of RNA from lung tissue and quantitative real-time PCR. Copy number estimates were generated from standard curves created by using selected reference cDNA templates and TaqMan probes (69).

Isolation of proteoglycans.

Cell medium was collected and combined with protease inhibitors (in mM: 5 benzamidine, 100 6-aminohexanoic acid, and 1 phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). The cell layer was rinsed with PBS and solubilized in 8 M urea buffer (8 M urea, 2 mM EDTA, 0 or 0.25 M NaCl, 50 mM Tris·HCl, and 0.5% Triton X-100 detergent, pH 7.4) containing protease inhibitors (67, 68). Media and cell layer extracts were concentrated and purified by ion-exchange chromatography on diethylaminoethyl-Sephacel in 8 M urea buffer with 0.25 M NaCl and eluted with 8 M urea buffer containing 3 M NaCl (67, 68).

Western immunoblotting.

For Western immunoblotting of versican, proteoglycans isolated by ion-exchange chromatography were digested with 0.05 U of chondroitin ABC lyase (North Star BioProducts, East Falmouth, MA) in 0.3 M Tris·HCl, pH 8.0, 0.6 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, and 18 mM sodium acetate with protease inhibitors for 3 h at 37°C and run on SDS-PAGE (4–12% with 3.5% stacking gel) under reducing conditions (44).

Statistical analysis.

Significance was evaluated by one- or two-way analysis of variance, with Bonferroni posttests as appropriate.

RESULTS

Roles of TLR2, TLR4, MyD88, and Trif in regulation of versican in macrophages treated with LPS.

Our previous work shows that E. coli LPS stimulates expression of versican in vivo in whole lungs and in vitro in BMDMs and alveolar macrophages (16, 76). A goal of this study was to define the involvement of TLR2, TLR4, and the adaptor molecules MyD88 and Trif in regulating versican expression in macrophages. First, we considered that standard LPS preparations primarily consist of the polysaccharide lipid A but may be contaminated with bacterial lipopeptides. While lipid A modulates the immune response via TLR4, lipopeptides interact with TLR2 (74). Therefore, macrophages from WT mice were exposed to the following: 1) a standard LPS preparation (LPS); 2) an ultrapure LPS (LPSEB) that only activates the TLR4 pathway; or 3) Pam3Csk, a synthetic lipopeptide that interacts with TLR2. Versican mRNA was expressed at very low abundance in unstimulated WT macrophages, with only 0.59 ± 0.02 copies/105 copies 18S. Treatment with LPS caused a 59.7 ± 11.6-fold (P < 0.0001 vs. untreated cells) increase in versican expression. LPSEB also caused a significant increase in versican (22.7 ± 2.6-fold, P < 0.01), but Pam3Csk did not (Fig. 1A), indicating that regulation of versican occurs in response to TLR4 but not TLR2 agonists.

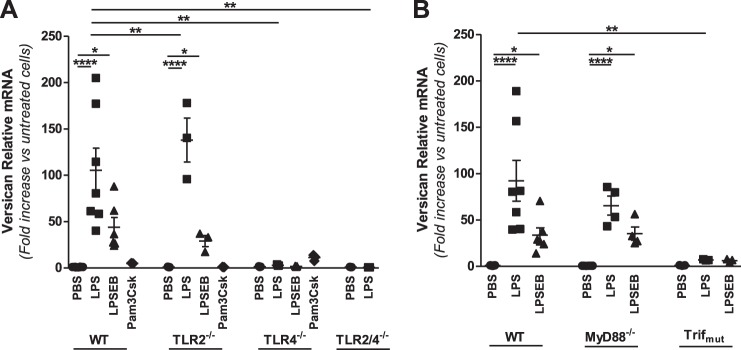

Fig. 1.

Role of TLR signaling molecules in LPS-mediated regulation of versican in macrophages. BMDMs from WT, TLR2−/−, TLR4−/−, or TLR2/4−/− (A) and WT, MyD88−/−, or Trifmutant (B) mice were treated with PBS, LPS (10 ng/ml), LPSEB (10 ng/ml), or Pam3Csk (10 μg/ml) for 4 h, as indicated (BMDMs from n = 3–7 mice per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001.

We next evaluated the effects of LPS on macrophages from mice deficient in TLR2 (TLR2−/−), TLR4 (TLR4−/−), or both TLR2 and TLR4 (TLR2/4−/−) (Fig. 1A). Versican was expressed at similarly low abundance in unstimulated macrophages from all of these deficient mice (not shown). In TLR2−/− macrophages, versican was significantly increased in response to LPS (138.0 ± 23.8-fold) and LPSEB (29.1 ± 6.0-fold) but not Pam3Csk, whereas in TLR4−/− macrophages versican was not increased in response to LPS, LPSEB, or Pam3Csk. Versican was undetectable in LPS-stimulated macrophages from mice deficient in both TLR2 and TLR4. The augmented versican response in TLR2−/− compared with WT macrophages likely reflects hyperresponsiveness of TLR4 commonly seen in TLR2−/− cells. Considering the differential responses to TLR2 and TLR4 agonists in WT cells and the differential responses to LPS in TLR2- and TLR4-deficient cells, these data indicate that TLR4 is essential for the versican response to LPS.

Individual TLRs differentially recruit intracellular adapter molecules that are critical links to subsequent TLR signaling events. TLR2 signaling utilizes solely the MyD88-TIRAP adapter pair, while TLR4 utilizes both the MyD88-TIRAP and Trif-TRAM adapter pairs, which control distinct aspects of the inflammatory response. Therefore, we also evaluated versican expression in macrophages from mice lacking MyD88 (MyD88−/−) or functional Trif (Trifmutant) (Fig. 1B). The versican response to LPS observed in WT macrophages remained elevated in MyD88−/− macrophages (72.9 ± 9.9-fold) but was markedly reduced in Trifmutant macrophages (7.0 ± 0.4-fold, P < 0.01 vs. WT LPS). Taken together, these data indicate that LPS-mediated regulation of versican requires TLR4 and the Trif adapter but not TLR2 or MyD88.

Roles of TLR2, TLR4, MyD88, and Trif in regulation of HAS1 in macrophages treated with LPS.

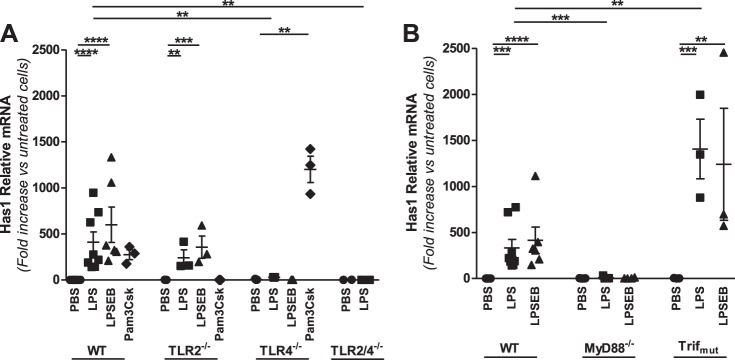

Like versican, HAS1 was expressed at very low abundance in unstimulated WT macrophages, with only 0.01 ± 0.01 copies/105 copies 18S. Treatment with LPS caused a marked 371.5 ± 70.3-fold (P < 0.001 vs. untreated cells) increase in HAS1 expression (Fig. 2A). LPSEB caused a significant increase in HAS1 (507.8 ± 118.0-fold, P < 0.0001), as did Pam3Csk (274.7 ± 53.5-fold, P < 0.01), indicating that HAS1 is regulated by both TLR2 and TLR4 agonists. In TLR2−/− macrophages HAS1 was significantly increased in response to both LPS (241.4 ± 87.0-fold, P < 0.01) and LPSEB (355.9 ± 120.7-fold, P < 0.001) but not Pam3Csk, whereas in TLR4−/− macrophages HAS1 was increased by Pam3Csk (1201.3 ± 143.1-fold, P < 0.0001) but not LPS or LPSEB. HAS1 was undetectable in LPS-stimulated macrophages from mice deficient in both TLR2 and TLR4. These data indicate that HAS1 expression is mediated through both TLR2 and TLR4. Finally, the HAS1 response to LPS was markedly reduced in MyD88−/− macrophages (8.3 ± 5.1-fold, P < 0.01) but still observed in Trifmutant macrophages (1407.6 ± 323.7-fold, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2B). Thus, unlike versican, LPS regulation of HAS1 involves both TLR2 and TLR4 and only the MyD88 adapter molecule but not Trif.

Fig. 2.

Role of TLR signaling molecules in LPS-mediated regulation of HAS1 in macrophages. BMDMs from WT, TLR2−/−, TLR4−/−, or TLR2/4−/− (A) and WT, MyD88−/−, or Trifmutant (B) mice were treated with PBS, LPS (10 ng/ml), LPSEB (10 ng/ml), or Pam3Csk (10 μg/ml) for 4 h, as indicated (BMDMs from n = 3–7 mice per group). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Roles of TLR2, TLR4, MyD88, and Trif in regulation of syndecan-4 in macrophages treated with LPS.

Syndecan-4 mRNA was expressed at higher abundance than versican or HAS1 in unstimulated WT macrophages, with 3,695 ± 543 copies/105 copies 18S, and increased 10.8 ± 1.1-fold (P < 0.0001 vs. untreated cells) in response to LPS (Fig. 3A). Both LPSEB (7.4 ± 1.1-fold, P < 0.0001) and Pam3Csk (5.4 ± 1.2-fold, P < 0.01) also increased syndecan-4 mRNA expression, indicating that regulation of syndecan-4 occurs with both TLR2 and TLR4 agonists as previously predicted (76). The syndecan-4 response observed in WT macrophages was maintained in TLR2−/− macrophages (16.4 ± 2.4-fold, P < 0.0001), only partially reduced in TLR4−/− macrophages (3.5 ± 0.6-fold, P < 0.01 vs. WT LPS), and undetectable in macrophages from mice deficient in both TLR2 and TLR4 (TLR2/4−/−). As with versican, the syndecan-4 response was augmented in TLR2−/− compared with WT macrophages. These data indicate that both TLR2 and TLR4 facilitate the syndecan-4 response to LPS. Finally, the syndecan-4 response was partially reduced in MyD88−/− macrophages (4.9 ± 0.6-fold, P < 0.0001 vs. WT LPS) but remained elevated in Trifmutant macrophages (8.4 ± 1.2-fold) (Fig. 3B). Therefore, unlike versican and HAS1, syndecan-4 is regulated by both TLR2 and TLR4 and involves both MyD88 and Trif adapter molecules.

Fig. 3.

Role of TLR signaling molecules in LPS-mediated regulation of syndecan-4 in macrophages. BMDMs from WT, TLR2−/−, TLR4−/−, or TLR2/4−/− (A) and WT, MyD88−/−, or Trifmutant (B) mice were treated with PBS, LPS (10 ng/ml), LPSEB (10 ng/ml), or Pam3Csk (10 μg/ml) for 4 h, as indicated (BMDMs from n = 3–7 mice per group). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Role of type I IFNs in regulation of versican, HAS1, and syndecan-4 in macrophages.

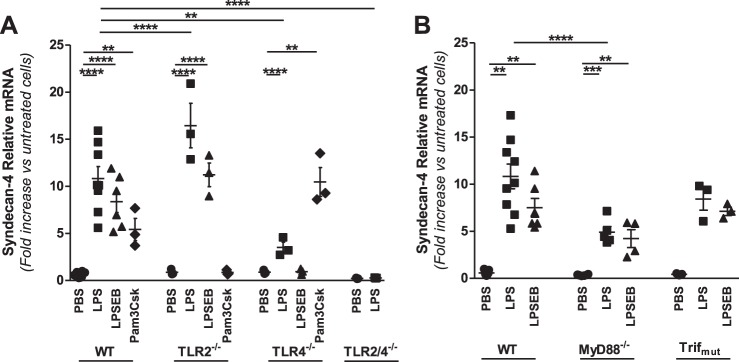

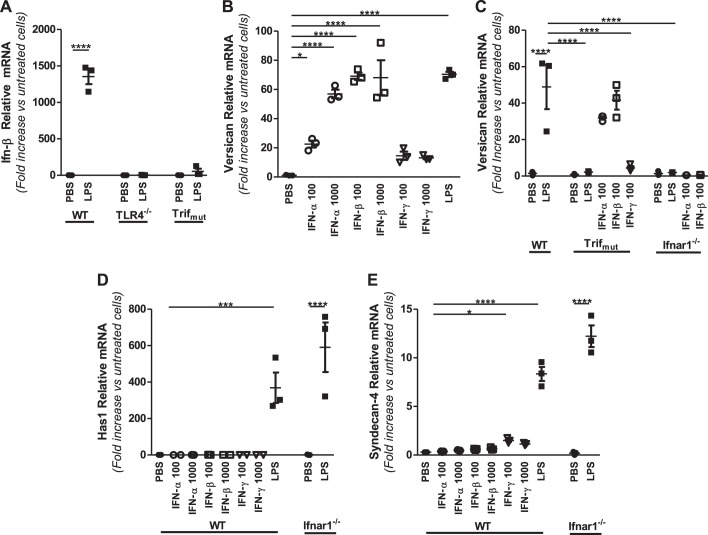

Activation of the Trif signaling pathway initiates a sequence of events involving phosphorylation of interferon regulatory factor (IRF)-3, transcription and secretion of type I IFNs, activation of type I IFN receptors (IFNARs), and consequent activation of type I IFN-responsive genes (31). Multiple approaches were taken to examine whether versican is an IFN-responsive gene. First, the well-described ability of LPS to stimulate IFN-β expression in macrophages from WT but not TLR4−/− or Trifmutant mice was verified under our experimental conditions (Fig. 4A) (12, 31, 56). Second, the ability of IFNs to directly stimulate versican expression by WT macrophages was examined. Type I IFNs, IFN-α and IFN-β, stimulated versican in a dose-dependent manner [IFN-α: 30.0 ± 5.7-fold at 100 U/ml and 102.3 ± 9.9-fold at 1,000 U/ml (P < 0.0001 vs. untreated cells); IFN-β: 82.7 ± 6.6-fold at 100 U/ml and 124.4 ± 12.2-fold at 1,000 U/ml (P < 0.0001 vs. untreated cells)] (Fig. 4B). The response to type I IFNs was markedly more robust than to the type II IFN, IFN-γ, which stimulated only a minor increase in versican {15.7 ± 2.0-fold at 100 U/ml and 11.5 ± 1.0-fold at 1,000 U/ml [nonsignificant (n.s.) vs. untreated cells]} (Fig. 4B). Third, the ability of treatment with IFNs to bypass the lack of functional Trif and stimulate versican expression was examined. Whereas LPS did not stimulate versican expression by Trifmutant macrophages (Fig. 1B), both type I IFNs did stimulate versican expression by Trifmutant macrophages [IFN-α: 31.9 ± 0.9-fold (P < 0.0001 vs. untreated cells); IFN-β: 41.6 ± 5.2-fold (P < 0.0001 vs. untreated cells)], comparably to the effects of LPS on WT macrophages (Fig. 4C). Fourth, the versican response was evaluated in macrophages from mice lacking the type I IFN receptor subunit 1 (Ifnar1−/−) (54). Neither LPS nor type I IFNs stimulate versican expression by Ifnar1−/− macrophages (Fig. 4C). These findings show that IFN-α and IFN-β mimic the effects of LPS on versican expression by macrophages from WT mice, that type I IFNs “rescue” versican expression in macrophages from Trifmutant mice, and that versican is not inducible in Ifnar1−/− macrophages, indicating that versican expression is regulated by Trif-dependent and type I IFN receptor signaling and is a type I IFN-stimulated gene (ISG) in macrophages.

Fig. 4.

Role of type I interferons and the type I interferon receptor in LPS-mediated regulation of versican, HAS1, and syndecan-4. A: BMDMs from WT, TLR4−/−, or Trifmutant mice were treated with PBS or LPS (10 ng/ml), as indicated. B: WT BMDMs were treated with PBS, IFN-α, -β, or -γ (100 and 1,000 U/ml), or LPS (10 ng/ml), as indicated. C–E: BMDMs from WT, Trifmutant, or Ifnar1−/− mice were treated with PBS, IFN-α, -β, or -γ (100 U/ml), or LPS (10 ng/ml), as indicated. All treatments were for 4 h (BMDMs from n = 3 mice per group). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

In contrast to the effects on versican expression, type I IFNs had no effect on either HAS1 or syndecan-4 expression by WT macrophages and LPS stimulated both HAS1 and syndecan-4 expression in Ifnar1−/− macrophages [HAS1: 590.7 ± 136.0-fold (P < 0.0001 vs. untreated cells); syndecan-4: 12.2 ± 1.1-fold (P < 0.0001 vs. untreated cells)] (Fig. 4, D and E). Thus neither HAS1 nor syndecan-4 is regulated by LPS via type I IFN receptor signaling.

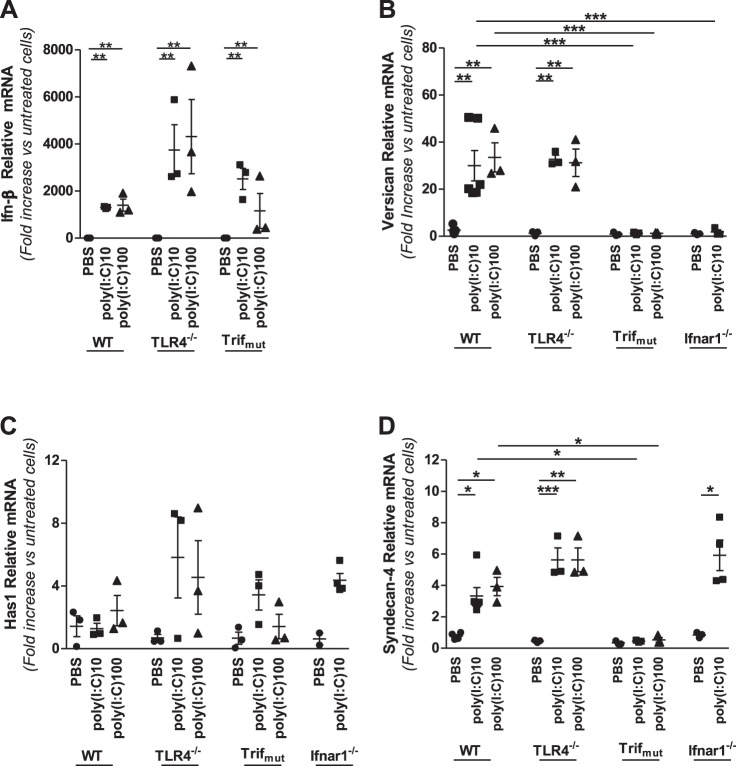

Role of Trif and type I IFN receptor in regulation of versican and syndecan-4 by poly(I:C) in macrophages.

Having defined that versican expression results from activation of the Trif-signaling arm of the TLR4 response to LPS, we next examined the effects of poly(I:C), whose interaction with TLR3 specifically activates the Trif adapter molecule (72). We first verified that poly(I:C) stimulates IFN-β expression in WT macrophages under our experimental conditions and that this effect is not dependent on TLR4 (Fig. 5A). Poly(I:C) also elicits an IFN-β response in macrophages lacking functional Trif (Fig. 5A), suggesting the additional involvement of retinoic acid-inducible gene-I (RIG-I)-like receptors (85). Treatment of macrophages from WT mice with 10 or 100 μg/ml poly(I:C) stimulated a 30.0 ± 6.5-fold (P < 0.01) or 33.5 ± 6.2-fold (P < 0.01) increase in versican expression, respectively (Fig. 5B). Versican was similarly stimulated by poly(I:C) treatment of TLR4−/− macrophages. However, poly(I:C) had no effect on versican by either Trifmutant or Ifnar1-deficient macrophages (Fig. 5B). Treatment with poly(I:C) had less of an impact on syndecan-4, causing only a modest increase in expression in WT and TLR4−/− but not Trifmutant macrophages (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, poly(I:C) did stimulate a modest increase in syndecan-4 expression in Ifnar1-deficient macrophages. Poly(I:C) had no significant impact on HAS1 expression in any of the macrophages examined (Fig. 5C). Thus, while LPS interacts with TLR4 to activate Trif and poly(I:C) interacts with TLR3 to activate Trif, both agonists trigger a downstream type I IFN signaling cascade that results in increased expression of versican by macrophages.

Fig. 5.

Involvement of TLR4, Trif, Ifn-β, and Ifnar1 in poly(I:C)-mediated regulation of versican, HAS1, and syndecan-4. A: BMDMs from WT, TLR4−/−, or Trifmutant mice were treated with PBS or poly(I:C) (10 or 100 μg/ml) for 4 h, as indicated. B–D: BMDMs from WT, TLR4−/−, Trifmutant, or Ifnar1−/− mice were treated with PBS or poly(I:C) (10 or 100 μg/ml) for 4 h, as indicated. (BMDM from n = 3–5 mice per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

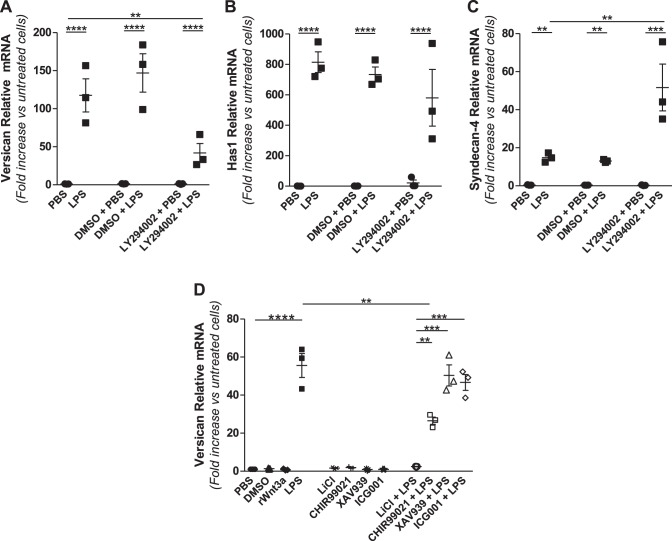

Role of signaling intermediary molecules in regulation of versican, HAS1, and syndecan-4.

We also investigated the role of PI3-kinase, which is a regulator of the switch from the MyD88-TIRAP phase to the TRIF-TRAM phase of the TLR4 response (3, 4) in mediating the expression of versican, HAS1, and syndecan-4. Pretreatment with the PI3-kinase chemical inhibitor LY29400 caused a significant reduction in the versican response to LPS (117.5 ± 21.7-fold without LY29400 vs. 46.3 ± 19.8-fold with LY294002, P < 0.01) (Fig. 6A), had no impact on the HAS1 response (814.6 ± 68.5-fold without LY29400 vs. 547.4 ± 196.8-fold with LY294002) (Fig. 6B), but caused a marked increase in the syndecan-4 response (14.8 ± 1.4-fold without LY294002 vs. 71.7 ± 32.1-fold with LY29400, P < 0.01) (Fig. 6C). Thus versican induction is positively regulated by PI3-kinase activity in macrophages exposed to LPS, but syndecan-4 is negatively regulated by PI3-kinase, and HAS1 is not regulated by PI3-kinase.

Fig. 6.

Effects of signaling inhibitors on versican, HAS1, and syndecan-4 expression. BMDMs from WT mice were pretreated with DMSO vehicle or 50 μM LY294002 (A–C) or 50 ng/ml rWnt3a, 30 mM LiCl, 5 μM CHIR99021, 5 μM XAV939, or 10 μM ICG001 (D) for 30–60 min before treatment with PBS or LPS (10 ng/ml) for 4 h, as indicated (BMDMs from n = 3 mice per group). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Work from other laboratories has shown that Wnt and growth factors activate the β-catenin/TCF/LEF-1 signaling pathway to increase expression of versican by smooth muscle cells (9, 62). Therefore, we evaluated whether the β-catenin/TCF/LEF-1 pathway is involved in LPS-mediated induction of versican by macrophages. To do this, we used several small-molecule inhibitors with different modes of action and different specificities. These included 1) lithium chloride, an inhibitor of glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) which is a negative regulator of Wnt signaling (18, 21, 58); 2) CHIR99021, a more selective and potent inhibitor of GSK-3 (8); 3) XAV939, an inhibitor of Wnt signaling via stabilization of Axin1 (34); and 4) ICG001, an inhibitor of Wnt signaling via interference with β-catenin-CREB interactions (23). Rahmani et al. showed that lithium chloride, which inhibits GSK-3 and allows for accumulation and nuclear translocation of β-catenin, stimulates versican expression by smooth muscle cells (62). In contrast, we found that lithium chloride alone did not stimulate versican expression [1.6 ± 0.3-fold (n.s. vs. untreated cells)] and completely inhibited LPS-mediated induction of versican in macrophages [55.6 ± 6.3-fold without lithium chloride vs. 2.4 ± 0.1-fold with lithium chloride (P < 0.0001)] (Fig. 6D). Similarly, CHIR99021 alone did not stimulate versican [1.8 ± 0.3-fold (n.s. vs. untreated cells)] and partially inhibited LPS-mediated induction of versican [55.6 ± 6.3-fold without CHIR99021 vs. 26.5 ± 1.9-fold with CHIR99021 (P < 0.01)]. Neither XAV939 nor ICG001 had any impact on LPS-mediated induction of versican (Fig. 6D). Further, none of the inhibitors tested had any impact on LPS-mediated induction of syndecan-4 (data not shown). In short, inhibitors of GSK-3 that are reported to facilitate β-catenin signaling do not induce versican expression in macrophages, and inhibitors that interfere with β-catenin signaling have no impact on the ability of LPS to induce versican expression in macrophages. Taken together, these data do not support a role for β-catenin signaling in modulating versican expression in macrophages. Rather, the ability of both lithium chloride and CHIR99021 to inhibit, rather than promote, LPS-mediated induction of versican suggests that GSK-3 does have a role in regulating versican expression by macrophages, though not via stabilization of β-catenin as in smooth muscle cells.

In summary, we describe key signaling events that regulate LPS- and poly(I:C)-mediated regulation of versican, HAS1, and syndecan-4 by macrophages. Versican expression involves TLR3, TLR4, Trif, and the type I IFN receptor. In contrast, HAS1 expression involves TLR2, TLR4, and MyD88, while syndecan-4 expression involves TLR2, TLR4, MyD88, and Trif. Thus regulation of these three extracellular matrix molecules occurs via distinct pathways. The importance of type I IFN signaling in the response to bacterial and viral pathogens suggests that macrophage-derived versican has a role in the innate immune response.

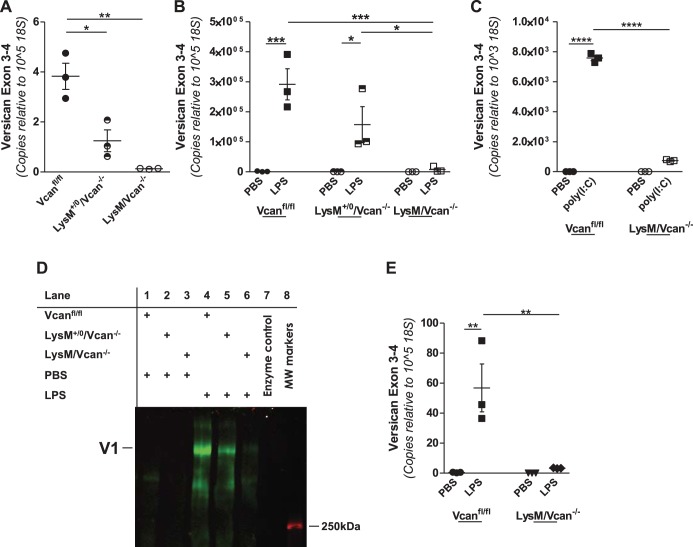

Characterization of versican expression by myeloid cells from WT and LysM/Vcan−/− mice.

To evaluate the role of macrophage-derived versican in the innate immune response, we developed LysM/Vcan−/− mice, which lack versican expression in cells expressing lysozyme 2, including macrophages. The targeting strategy has been described. In brief, deletion of exon 4 results in a premature STOP codon that yields a severely truncated form of versican lacking both α- and β-GAG attachment regions as well as other downstream functional domains of the versican protein (55). To verify the impact of deletion of exon 4 on versican expression, in vitro studies were performed with BMDMs, alveolar macrophages, and bone marrow neutrophils from WT and LysM/Vcan−/− mice. Versican mRNA is constitutively expressed at a low level in WT BMDMs (3.83 ± 0.52 copies per 105 copies of 18S). Versican is reduced in BMDMs from LysM+/0/Vcan−/− mice, which are hemizygous for Lysozyme 2-Cre [1.25 ± 0.43 copies per 105 copies of 18S (P < 0.05 vs. WT)], and reduced even further in BMDMs from LysM/Vcan−/− mice, which are homozygous for Lysozyme 2-Cre [0.13 ± 0.01 copies per 105 copies of 18S (P < 0.01 vs. WT)] (Fig. 7A). The ability of LPS to induce versican mRNA in WT macrophages (292,000 ± 52,000 copies per 105 copies of 18S) was decreased in LysM+/0/Vcan−/− mice [129,000 ± 79,000 copies per 105 copies of 18S (n.s. vs. WT)] and further decreased in LysM/Vcan−/− mice [7,900 ± 5,300 copies per 105 copies 18S (P < 0.001 vs. WT)] (Fig. 7B), a reduction of 97%. Similarly, the ability of poly(I:C) to induce versican in WT BMDMs (7,580 ± 429 copies per 103 copies of) was decreased in LysM/Vcan−/− mice (738 ± 89 copies per 105 copies of 18S, P < 0.001 vs. WT) (Fig. 7C), a reduction of 90%. Versican protein was evaluated by Western immunoblotting using α- and β-GAG antibodies. Versican protein was undetectable in the culture media of unstimulated macrophages (Fig. 7D, lanes 1–3). LPS stimulated secretion of the versican isoform V1 by WT macrophages, as indicated by positive reactivity with the β-GAG antibody (Fig. 7D, lane 4), but not the α-GAG antibody (data not shown). The ability of LPS to induce versican protein production (Fig. 7D, lane 4) was attenuated in macrophages from LysM+/0/Vcan−/− mice (Fig. 7D, lane 5) and was barely detectable in macrophages from LysM/Vcan−/− mice (Fig. 7D, lane 6). No versican was detected associated with the cell layer (data not shown). As with BMDMs, versican mRNA was constitutively expressed at a very low level in alveolar macrophages from WT (0.07 ± 0.01 copies per 105 copies of 18S) and LysM/Vcan−/− [0.07 ± 0.01 copies per 105 copies of 18S (n.s. vs. WT)] mice and the ability of LPS to induce versican in WT alveolar macrophages (56.83 ± 15.95 copies per 105 copies of 18S) was decreased in LysM/Vcan−/− [3.31 ± 0.12 copies per 105 copies of 18S (P < 0.01 vs. WT)] mice, a 94% reduction in versican mRNA (Fig. 7E). This result justifies the use of BMDMs for the majority of these studies, as alveolar macrophages are of more limited availability. Versican also was expressed in low abundance in WT bone marrow neutrophils (5.75 ± 0.47 copies per 105 copies of 18S), and expression was not increased by treatment with LPS in neutrophils from WT or LysM/Vcan−/− mice (data not shown). Expression in nonmyeloid cells was also examined. Versican was constitutively expressed at similar levels in lung fibroblasts of both WT (981.65 ± 113.71 copies per 105 copies of 18S) and LysM/Vcan−/− [836.83 ± 95.26 copies per 105 copies of 18S (n.s. vs. WT)] mice and was not altered by LPS in fibroblasts of either lineage (data not shown). These findings demonstrate that the targeting strategy was successful for decreasing basal and LPS-stimulated versican gene expression in macrophages.

Fig. 7.

Targeting strategy for generation of Vcanfl/fl mice and characterization of macrophages from LysM/Vcan−/− mice. A: unstimulated BMDMs from WT (Vcanfl/fl), LysM+/0/Vcan−/−, or LysM/Vcan−/− mice were evaluated for basal levels of versican mRNA. B: BMDMs from WT (Vcanfl/fl), LysM+/0/Vcan−/−, or LysM/Vcan−/− mice were treated with PBS or LPS (10 ng/ml) for 4 h, as indicated. C: BMDMs from WT (Vcanfl/fl) or LysM/Vcan−/− mice were treated with PBS or poly(I:C) (100 μg/ml) for 4 h, as indicated. D: BMDMs from WT (Vcanfl/fl), LysM+/0/Vcan−/−, or LysM/Vcan−/− mice were treated with PBS or LPS (10 ng/ml) for 24 h, as indicated. Secreted proteoglycans were purified from the media and analyzed by Western immunoblotting. E: alveolar macrophages from WT or LysM/Vcan−/− mice were treated with PBS or LPS (10 ng/ml) for 4 h, as indicated. BMDMs or alveolar macrophages from n = 3 mice per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

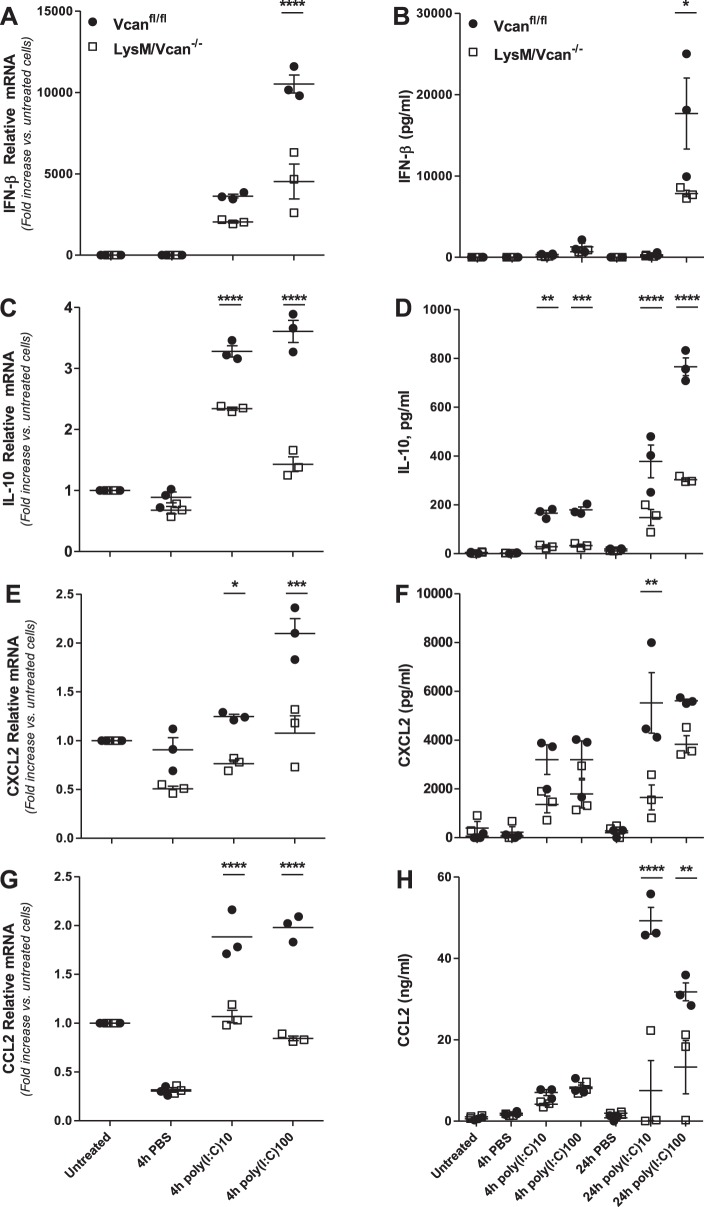

Evaluation of response to treatment of LysM/Vcan−/− BMDMs with TLR3 agonist poly(I:C).

In vitro experiments were performed to assess the role of macrophage-derived versican in the inflammatory response. To specifically evaluate Trif-mediated signaling, studies were performed with poly(I:C) rather than LPS, which activates MyD88- and Trif-dependent signaling. Thus poly(I:C)-stimulated chemokine and cytokine production was evaluated in control and LysM/Vcan−/− macrophages. The ability of poly(I:C) to stimulate mRNA expression of IFN-β (Fig. 8A), IL-10 (Fig. 8C), CXCL2 (Fig. 8E), and CCL2 (Fig. 8G) in control macrophages was significantly reduced in LysM/Vcan−/− macrophages (IFN-β: 57% reduction; IL-10: 60%; CXCL2: 46%; CCL2: 57%). Similarly, the ability of poly(I:C) to stimulate secreted protein levels for these molecules was also reduced in versican-deficient macrophages (IFN-β: 45% reduction; IL-10: 60%; CXCL2: 66%; CCL2: 78%) (Fig. 8, B, D, F, and H). Poly(I:C)-induced mRNA for TNF-α and IL-6 in control macrophages also was decreased in LysM/Vcan−/− macrophages; however, there were no differences in secreted protein levels of these cytokines (data not shown). There was no difference in poly(I:C)-stimulated CXCL1 mRNA or protein in control or LysM/Vcan−/− macrophages (data not shown). Thus the lack of versican impacts expression of select anti-inflammatory (IFN-β and IL-10) and proinflammatory (CXCL2, CCL2) chemokines and cytokines by macrophages. These findings suggest that macrophage-derived versican contributes to the cytokine and chemokine expression and production in BMDMs.

Fig. 8.

Cytokine and chemokine production by LysM/Vcan−/− macrophages. Fold changes in the mRNA from cell lysates (A, C, E, G) and amount of cytokines and chemokines from supernatant (B, D, F, H) of BMDMs from control (Vcanfl/fl) and LysM/Vcan−/− mice 24 h after treatment with poly(I:C) (10 and 100 ng/ml) (BMDMs from n = 3 mice per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

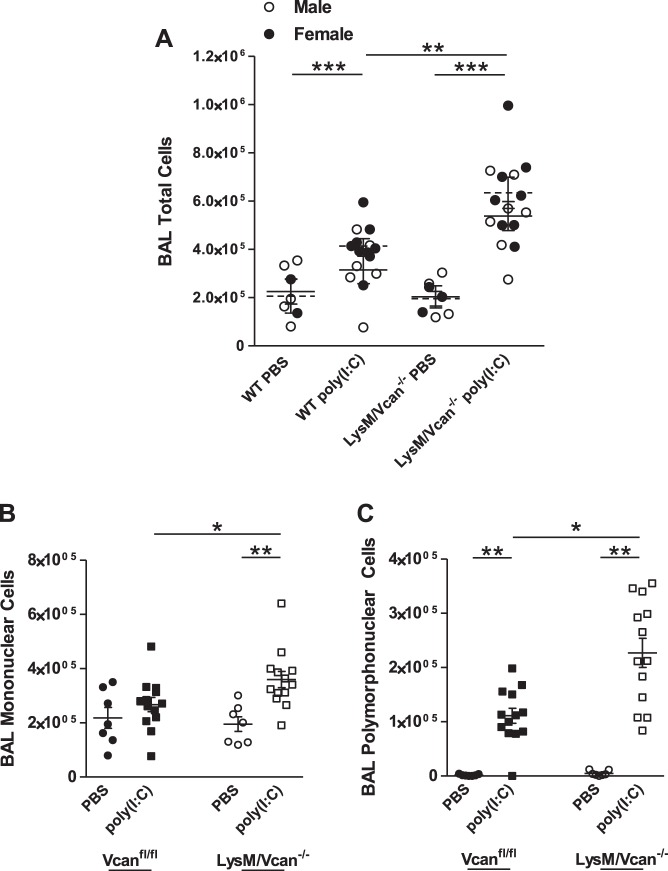

Evaluation of innate immune response to oropharyngeal treatment of LysM/Vcan−/− mice with TLR3 agonist poly(I:C).

In vivo studies were performed to evaluate the role of macrophage-derived versican in the inflammatory response to poly(I:C). Exposure to oropharyngeal poly(I:C) (50 μg/mouse or ~1 μg/g) for 24 h elicited a mild inflammatory response in WT mice, indicated by leukocyte migration into the pulmonary air space measured by differential cell counts recovered in BAL fluid [3.7 ± 0.3 × 105 total cells (P < 0.05 vs. PBS-treated WT mice)]. Poly(I:C) elicited a more robust inflammatory response in LysM/Vcan−/− mice, as suggested by increased total inflammatory cell recruitment {5.9 ± 0.4 × 105 total cells [P < 0.001 vs. poly(I:C)-treated WT mice]}, with no differences observed in pulmonary recruitment of leukocytes into the lungs of male and female mice (Fig. 9A). Increased total inflammatory cell recruitment was attributable to increases in both mononuclear [2.7 ± 0.2 × 105 WT vs. 3.6 ± 0.3 × 105 LysM/Vcan−/− mice (P < 0.05)] (Fig. 9B) and polymorphonuclear [1.1.0 ± 0.1 × 105 WT vs. 2.3 ± 0.2 × 105 LysM/Vcan−/− mice (P < 0.001)] (Fig. 9C) cell populations.

Fig. 9.

Cellular recruitment into air space of lungs of LysM/Vcan−/− mice. WT and LysM/Vcan−/− mice were exposed to oropharyngeal treatment with poly(I:C) (50 μg/mouse). Bronchoalveolar lavage was performed after 24 h, and differential cell counts were analyzed in lavage fluid. Values are shown for total (A), mononuclear (B), and polymorphonuclear (C) cells (n = 7–13 mice per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

The differences in mononuclear and polymorphonuclear cell recruitment suggested that there might also be differences in pulmonary levels of chemokines and cytokines responsible for myeloid cell recruitment and the inflammatory response. BAL fluid of LysM/Vcan−/− mice had decreased poly(I:C)-stimulated levels of IFN-β [20.4% vs. poly(I:C)-treated WT mice (P < 0.05)] (Fig. 10A), IL-10 [29.3% (P < 0.05)] (Fig. 10B), CCL2/MCP-1 [55.0% (P < 0.05)] (Fig. 10C), CXCL2/MIP2 [24.9% (P < 0.01)] (Fig. 10D), IL-6 [51.2% (P < 0.001)] (Fig. 10E), and TNF-α [29.0% (P < 0.01)] (Fig. 10F). Thus levels of anti-inflammatory IFN-β and IL-10 were decreased in vivo in lungs of mice with versican-deficient macrophages similarly as in vitro in versican-deficient macrophages themselves (Fig. 8). Levels of the monocyte-recruiting chemokine CCL2 and the neutrophil-recruiting chemokine CXCL2 also were similarly decreased in vivo in lungs of mice with versican-deficient macrophages as in vitro in versican-deficient macrophages themselves (Fig. 8). However, CXCL1 did not differ in lungs of poly(I:C)-treated WT vs. LysM/Vcan−/− mice, similar to the lack of difference observed in vitro in macrophages. These data indicate that LysM/Vcan−/− mice have a heightened pulmonary inflammatory response to poly(I:C), as indicated by greater inflammatory cell recruitment. Similar decreases in IFN-β, IL-10, CCL2, and CXCL2 in supernatant of BMDMs and BAL fluid after exposure to poly(I:C) suggest that macrophage-derived versican in part plays an important role in modulating this response in lungs.

Fig. 10.

Recovery of cytokines and chemokines in lungs of LysM/Vcan−/− mice. WT and LysM/Vcan−/− mice were exposed to oropharyngeal treatment with poly(I:C) (50 μg/mouse). A: IFN-β. B: IL-10. C: CCL2/MCP-1. D: CXCL2/MIP2. E: IL-6. F: TNF-α. G: CXCL1/KC. Bronchoalveolar lavage was performed after 24 h, and ELISAs were performed on cell-free lavage fluid (n = 3–7 mice per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we first defined the signaling pathway(s) regulating versican expression in macrophages exposed to the TLR agonists LPS and poly(I:C) and second evaluated the role of the versican-enriched matrix formed by macrophages in lungs of mice exposed to poly(I:C). To accomplish this, we developed a genetically engineered strain of mice that allowed for the deletion of exon 4 of versican in cells expressing Cre recombinase under control of the Lysozyme M promoter, which includes macrophages, neutrophils, and type II epithelial cells in lungs (35, 50). We report four major findings. First, type I IFN signaling is essential for versican expression by macrophages. Second, macrophage-derived versican is essential for IFN-β and IL-10 expression by macrophages. Third, mice with macrophages deficient in versican have increased inflammatory cell recruitment into lungs in response to poly(I:C). Fourth, mice with macrophages deficient in versican have diminished levels of IFN-β and IL-10 in lungs in response to poly(I:C). Taken together, these results suggest that macrophage-derived versican is an ISG that limits inflammatory cell recruitment and promotes production of key anti-inflammatory cytokines, IFN-β and IL-10, in the pulmonary response to poly(I:C). In the context of the studies performed, macrophage-derived versican is an immunomodulatory molecule that is anti-inflammatory.

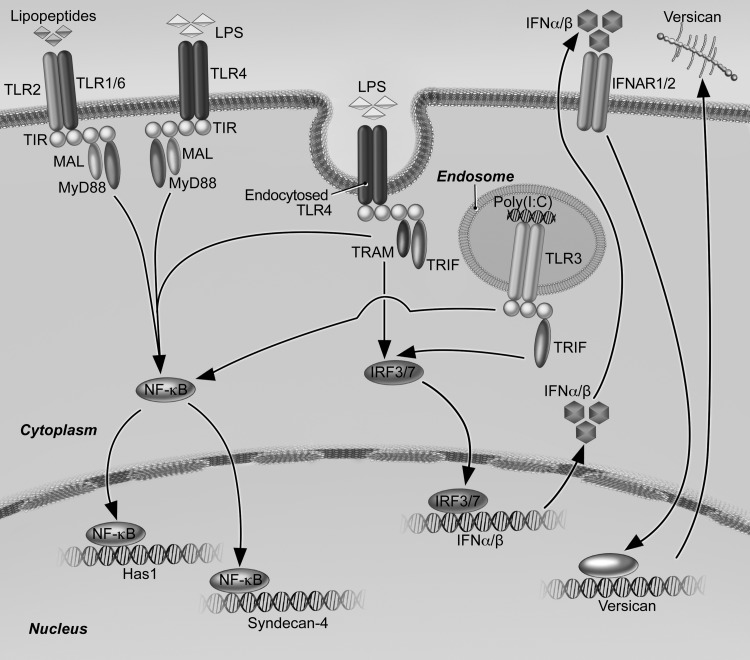

Our findings that E. coli LPS and poly(I:C) stimulate versican expression by macrophages via a signaling cascade that involves the Trif adapter, type I IFNs, and the type I IFN receptor identify versican as an ISG (Fig. 11). We present the Trif/type I IFN pathway regulating versican expression in macrophages as an alternative pathway to the β-catenin/TCF/LEF pathway previously shown to regulate versican expression in smooth muscle cells (62). Whereas our results do not support a role for β-catenin signaling in modulating versican expression in macrophages, other studies suggest cross talk between these pathways (28). IFN-β mediates phosphorylation and inactivation of GSK-3 in dendritic and T cells (78), which should promote β-catenin signaling (78) and, consequently, versican expression. However, we find that inhibition of GSK-3 in BMDMs inhibits rather than promotes LPS-mediated versican expression. A possible explanation might be that the β-catenin/TCF/LEF and TLR/Trif/type I IFN signaling pathways are differentially regulated in an agonist- or cell-specific manner. This is supported by studies showing that versican expression is increased in macrophages but not in fibroblasts or epithelial cells treated with LPS and poly(I:C) (16, 60). Given the new understanding that two pathways regulate versican expression, several key questions are raised that need to be addressed in future studies. These include determination of the cellular specificity of the Trif/type I IFN and β-catenin/TCF/LEF pathways; identification of the signaling pathways and cellular sources contributing to versican expression in lungs exposed to viruses and bacteria; and identification of the signaling molecules and transcription factors regulating the increased expression of versican in response to activation of type I receptor signaling.

Fig. 11.

Schematic depicting pathways by which LPS and poly(I:C) regulate expression of versican, HAS1, and syndecan-4. Engagement of macrophage Toll-like receptors TLR4 and TLR3 by LPS and poly(I:C), respectively, result in enhanced versican expression. Subsequent to activation of TLR4 and TLR3, engagement of the TRIF adaptor molecule is known to activate transcription factors IRF3/7 that lead to production of type I interferons (IFN-α/-β) and recognition by type I interferon receptors (IFNAR1/2). Signaling events downstream of IFNAR activation lead to production of versican; the transcription factor(s) mediating expression of versican in this response is still to be determined. In contrast, expression of both HAS1 and syndecan-4 result from TLR4- and TLR2-mediated engagement of the MyD88 adaptor molecule. In addition, syndecan-4 expression results from TLR4- and TLR3-mediated engagement of TRIF and downstream signaling events that are independent of type I IFNs.

To further evaluate the role of macrophage-derived versican, we needed a versican-deficient model. However, versican deficiency in the hdf mouse results in cardiac development defects that are embryonically lethal (51). We therefore undertook development of two strains of mice with conditional deficiency in versican: B6.Rosa26-CreERT+/−/Vcanfl/fl mice, abbreviated as Vcan−/−, that have a global deletion of versican when treated with tamoxifen (37), and B6.LysM-Cre+/+/Vcanfl/fl mice, abbreviated as LysM/Vcan-/–, which lack versican in macrophages. Studies performed in Vcan−/− mice showed that the versican-enriched matrix formed in response to poly(I:C) promotes leukocyte adhesion and migration, suggesting the formation of a proinflammatory matrix (37). For the present study, we used LysM/Vcan−/− mice to evaluate the contribution of macrophage-derived versican to the inflammatory response. In in vitro experiments, we showed that macrophages from LysM/Vcan−/− mice secrete less IFN-β in response to poly(I:C) than control cells. Thus type I IFNs regulate versican expression and versican regulates IFN-β expression by macrophages, indicating a feedback regulatory process that might potentiate the effects of type I IFNs. This interdependence is analogous to the coregulation of versican and CXCL1 expression in the response to ultraviolet light exposure (73). Macrophages from LysM/Vcan−/− mice also secrete less IL-10 in response to poly(I:C) than control cells. Thus activation of Trif/type I IFN signaling in macrophages induces versican expression, which in turn influences production of two important anti-inflammatory cytokines, IFN-β and IL-10. These findings are consistent with a recent report by Tang and colleagues, who showed that versican reprograms dendritic cells to an immunosuppressive phenotype through a TLR2-dependent regulation of autocrine IL-6 and IL-10 production and upregulation of their respective cell surface receptors (75). One difference between our work and that of Tang et al. is that there was no difference in the expression or production of IL-6 when BMDM supernatants from WT and LysM/Vcan−/− mice were compared. This may be due to differences in experimental design or to differences in the ability of versican to modulate IL-6 production in macrophages vs. dendritic cells. Macrophages from LysM/Vcan−/− mice also secreted less CXCL2 and CCL2 when exposed to poly(I:C). In contrast, there was no difference in the expression or production of CXCL1 when macrophages obtained from LysM/Vcan−/− mice were compared to BMDMs from WT mice treated with poly(I:C). Interestingly, studies by Takemori et al. using UVB irradiated mouse embryonic fibroblasts found that versican was responsible for the increased production of CXCL1 by these stromal cells (73). Differences observed in the immunomodulatory effects of versican on macrophages, dendritic cells, and fibroblasts need further characterization to better understand how this CSPG differentially regulates the inflammatory phenotype of myeloid and stromal cells.

The finding that macrophages deficient in versican had a significant decrease in the production of two anti-inflammatory cytokines, IFN-β and IL-10, and two proinflammatory chemokines, CXCL2 and CCL2, when treated with poly(I:C) raised important questions as to the role of versican in the innate immune response in lungs. To specifically activate Trif-dependent signaling, male and female mice were treated with a single dose of oropharyngeal poly(I:C) and then followed for 24 h. This study showed increased recruitment of monocytes and neutrophils into lungs of LysM/Vcan−/− mice compared with control mice. The finding of increased trafficking of leukocytes into the lungs of mice with macrophages deficient in versican suggests that versican limits inflammatory cell recruitment in this model of pulmonary inflammation, further supporting a role for macrophage-derived versican as an immunosuppressive molecule. This contrasts with our findings in globally deficient Vcan−/− mice, in which poly(I:C) resulted in decreased pulmonary inflammatory cell recruitment, suggesting that versican promotes leukocyte migration through increased adhesion and leukocyte migration (37). Differences in dosage and timing of poly(I:C) administration between these two studies must be considered. However, as discussed above, the cellular source(s) (e.g., macrophages vs. fibroblasts) of versican or the cells, chemokines, or TLRs that versican acts upon might well determine its role in providing fine control of the innate immune response and require further study (24, 39, 42, 60, 83, 86).

To further characterize the inflammatory response to poly(I:C), we measured several cytokines and chemokines in BAL fluid. This showed decreased recovery of IFN-β and IL-10 in BAL fluid of poly(I:C)-treated LysM/Vcan−/− mice compared with control mice, which is similar to our in vitro findings with LysM/Vcan−/− BMDMs and our previous in vivo findings when Vcan−/− mice were treated with poly(I:C) (37). These in vitro and in vivo findings suggest that macrophage-derived versican produced in response to poly(I:C)-mediated activation of Trif-dependent signaling is in large part responsible for production of IFN-β and IL-10 in lungs of both versican-deficient mouse strains. Similar to our in vitro findings, we also observed a significant decrease in CXCL2 and CCL2 but no difference in the recovery of CXCL1 when LysM/Vcan−/− and control mice were compared. In addition, we found a significant decrease in the recovery of IL-6 and TNF-α in the BAL fluid of LysM/Vcan−/− mice compared with control mice. The finding that IL-6 and TNF-α were not altered in supernatants of BMDMs but were decreased in BAL fluid from LysM/Vcan−/− mice suggests that versican regulates the expression of these cytokines in other cells in lungs of mice exposed to poly(I:C). The findings that similar cytokines and chemokines (i.e., type I IFNs, IL-10, CXCL2, CCL2, IL-6, and TNF-α) were decreased in the lungs of both strains of versican-deficient mice (i.e., LysM/Vcan−/− and Vcan−/− mice) increase our confidence that the change in the production of these cytokines is dependent on the increased expression and accumulation of versican in the lungs of mice treated with poly(I:C) (37).

In brief, evidence from LysM/Vcan−/− mice suggests an anti-inflammatory role for versican, while evidence from Vcan−/− mice suggests a proinflammatory role for versican (37, 82). Our findings suggest that the ability of versican to modulate the innate immune system is contextual and will depend on the specific agonist, signaling pathway, or cell responsible for the increased expression of versican; the temporal phase of the inflammatory response; or possibly the tissue compartment where versican accumulates. The finding that both proinflammatory (i.e., TNF-α, IL-6, CXCL2, and CCL2) and anti-inflammatory (i.e., IL-10 and IFN-β) cytokines are decreased in lungs of both strains of versican-deficient mice treated with poly(I:C) makes it difficult to definitively define the mechanism(s) whereby versican controls pulmonary inflammation. Even though these mechanisms are not fully understood, this body of work does provide evidence that versican is an immunomodulatory molecule providing fine control of innate immunity.

In addition to defining the signaling events mediating versican expression, we also defined key signaling events leading to HAS1 and syndecan-4 expression in macrophages exposed to LPS and poly(I:C). Our previous work shows that HAS1 is the isoform of hyaluronan synthase that is selectively upregulated in lungs and macrophages of mice exposed to LPS and live E. coli (16). Similarly, we have shown that syndecan-4 is the heparan sulfate proteoglycan that is selectively upregulated in response to exposure to gram-negative bacteria (76). Studies with Syn4−/− mice indicated that syndecan-4 functions to limit the extent of pulmonary inflammation and lung injury following bacterial infection (76). However, the timing by which these molecules impact the inflammatory response differs. We now know that each of these molecules is regulated by distinct pathways. This knowledge helps to explain the differences in the pulmonary expression of these genes (16, 76). Versican expression is controlled by TLR4- and TLR3-mediated engagement of Trif and subsequent type I IFN receptor signaling. In contrast, increased HAS1 and syndecan-4 expression result from TLR4- and TLR2-mediated engagement of the MyD88 adapter molecule. Syndecan-4 expression also results from TLR3-mediated engagement of Trif and downstream signaling events that are independent of type I IFNs. This new understanding now allows us to explain differences in the expression of versican, HAS1, and syndecan-4 in lungs of mice treated with LPS that we have previously reported (16, 76). These studies showed that the expression of syndecan-4 and HAS1 are the highest at 2 h after instillation of LPS, while peak mRNA expression of versican in lungs was observed at 6 h. These differences are consistent with the timing of PI3-kinase-driven transition from MyD88 to Trif signaling, with the former pathway occurring more rapidly and the latter more slowly (30, 56). Our findings presented here and those of others confirm the involvement of PI3-kinase in regulating versican expression (13, 73). The rapid increase in HAS1 by 2 h after instillation of LPS reflects the immediate engagement and activation of MyD88 downstream signaling events. The ensuing rapid decrease in HAS1 is indicative of the sole involvement of the MyD88 adaptor molecule. Similarly, the rapid increase in syndecan-4 also by 2 h after instillation of LPS is consistent with the immediate engagement of MyD88. However, the more gradual decline in syndecan-4 reflects the additional involvement of the Trif adaptor molecule. Finally, the slightly later peak versican response at 6 h reflects the slower onset of Trif signaling and the requirement for induction of type I IFNs. Thus we are now beginning to understand the subtleties in how different proteoglycans differentially impact the inflammatory response. MyD88-regulated expression of syndecan-4 functions in the more immediate anti-inflammatory response, with Trif-regulated expression of versican taking over in the slightly later phase of the response. Evidence now indicates that upregulation of select extracellular matrix molecules in response to TLR activation is an important component of the pulmonary anti-inflammatory response and suggests potential targets for therapeutic intervention.

GRANTS

Development of the genetically engineered mice was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants R21 RR-030249 (to C. W. Frevert), P01 HL-098067 (to T. N. Wight, C. W. Frevert), and U19 AI-125378 (to T. N. Wight).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.Y.C., M.G.K., K.R.B., T.N.W., and C.W.F. conceived and designed research; M.Y.C., K.R.B., and T.W. performed experiments; M.Y.C., K.R.B., and C.W.F. analyzed data; M.Y.C., M.G., A.M.M., K.R.B., T.W., W.A.A., and C.W.F. interpreted results of experiments; M.Y.C. and C.W.F. prepared figures; M.Y.C. and C.W.F. drafted manuscript; M.Y.C., I.K., M.G., A.M.M., M.G.K., K.R.B., T.W., W.C.P., W.A.A., T.N.W., and C.W.F. edited and revised manuscript; M.Y.C., I.K., M.G., A.M.M., M.G.K., K.R.B., T.W., W.C.P., W.A.A., T.N.W., and C.W.F. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dowon An for dedication and hard work related to the animal studies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi O, Kawai T, Takeda K, Matsumoto M, Tsutsui H, Sakagami M, Nakanishi K, Akira S. Targeted disruption of the MyD88 gene results in loss of IL-1- and IL-18-mediated function. Immunity 9: 143–150, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80596-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akira S. Toll-like receptors: lessons from knockout mice. Biochem Soc Trans 28: 551–556, 2000. doi: 10.1042/bst0280551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aksoy E, Taboubi S, Torres D, Delbauve S, Hachani A, Whitehead MA, Pearce WP, Berenjeno IM, Nock G, Filloux A, Beyaert R, Flamand V, Vanhaesebroeck B. The p110δ isoform of the kinase PI(3)K controls the subcellular compartmentalization of TLR4 signaling and protects from endotoxic shock. Nat Immunol 13: 1045–1054, 2012. (Erratum. Nat Immunol 14: 877, 2013). doi: 10.1038/ni.2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aksoy E, Vanden Berghe W, Detienne S, Amraoui Z, Fitzgerald KA, Haegeman G, Goldman M, Willems F. Inhibition of phosphoinositide 3-kinase enhances TRIF-dependent NF-kappa B activation and IFN-beta synthesis downstream of Toll-like receptor 3 and 4. Eur J Immunol 35: 2200–2209, 2005. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersson-Sjöland A, Hallgren O, Rolandsson S, Weitoft M, Tykesson E, Larsson-Callerfelt AK, Rydell-Törmänen K, Bjermer L, Malmström A, Karlsson JC, Westergren-Thorsson G. Versican in inflammation and tissue remodeling: the impact on lung disorders. Glycobiology 25: 243–251, 2015. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwu120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arimori Y, Nakamura R, Yamada H, Shibata K, Maeda N, Kase T, Yoshikai Y. Type I interferon limits influenza virus-induced acute lung injury by regulation of excessive inflammation in mice. Antiviral Res 99: 230–237, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ayars AG, Altman LC, Potter-Perigo S, Radford K, Wight TN, Nair P. Sputum hyaluronan and versican in severe eosinophilic asthma. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 161: 65–73, 2013. doi: 10.1159/000343031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baarsma HA, Engelbertink LH, van Hees LJ, Menzen MH, Meurs H, Timens W, Postma DS, Kerstjens HA, Gosens R. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) regulates TGF-β1-induced differentiation of pulmonary fibroblasts. Br J Pharmacol 169: 590–603, 2013. doi: 10.1111/bph.12098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baarsma HA, Menzen MH, Halayko AJ, Meurs H, Kerstjens HA, Gosens R. β-Catenin signaling is required for TGF-β1-induced extracellular matrix production by airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 301: L956–L965, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00123.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baarsma HA, Spanjer AI, Haitsma G, Engelbertink LH, Meurs H, Jonker MR, Timens W, Postma DS, Kerstjens HA, Gosens R. Activation of WNT/β-catenin signaling in pulmonary fibroblasts by TGF-β1 is increased in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS One 6: e25450, 2011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bensadoun ES, Burke AK, Hogg JC, Roberts CR. Proteoglycan deposition in pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 154: 1819–1828, 1996. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.6.8970376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beutler B, Rietschel ET. Innate immune sensing and its roots: the story of endotoxin. Nat Rev Immunol 3: 169–176, 2003. doi: 10.1038/nri1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cardoso LE, Little PJ, Ballinger ML, Chan CK, Braun KR, Potter-Perigo S, Bornfeldt KE, Kinsella MG, Wight TN. Platelet-derived growth factor differentially regulates the expression and post-translational modification of versican by arterial smooth muscle cells through distinct protein kinase C and extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathways. J Biol Chem 285: 6987–6995, 2010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.088674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cerwenka A, Morgan TM, Harmsen AG, Dutton RW. Migration kinetics and final destination of type 1 and type 2 CD8 effector cells predict protection against pulmonary virus infection. J Exp Med 189: 423–434, 1999. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang MY, Chan CK, Braun KR, Green PS, O’Brien KD, Chait A, Day AJ, Wight TN. Monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation: synthesis and secretion of a complex extracellular matrix. J Biol Chem 287: 14122–14135, 2012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.324988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang MY, Tanino Y, Vidova V, Kinsella MG, Chan CK, Johnson PY, Wight TN, Frevert CW. A rapid increase in macrophage-derived versican and hyaluronan in infectious lung disease. Matrix Biol 34: 1–12, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clausen BE, Burkhardt C, Reith W, Renkawitz R, Förster I. Conditional gene targeting in macrophages and granulocytes using LysMcre mice. Transgenic Res 8: 265–277, 1999. doi: 10.1023/A:1008942828960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen P, Goedert M. GSK3 inhibitors: development and therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Drug Discov 3: 479–487, 2004. doi: 10.1038/nrd1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coulson-Thomas VJ, Gesteira TF, Hascall V, Kao W. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells suppress host rejection: the role of the glycocalyx. J Biol Chem 289: 23465–23481, 2014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.557447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.da Silva Correia J, Soldau K, Christen U, Tobias PS, Ulevitch RJ. Lipopolysaccharide is in close proximity to each of the proteins in its membrane receptor complex. Transfer from CD14 to TLR4 and MD-2. J Biol Chem 276: 21129–21135, 2001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009164200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davies SP, Reddy H, Caivano M, Cohen P. Specificity and mechanism of action of some commonly used protein kinase inhibitors. Biochem J 351: 95–105, 2000. doi: 10.1042/bj3510095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Day AJ, de la Motte CA. Hyaluronan cross-linking: a protective mechanism in inflammation? Trends Immunol 26: 637–643, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delgado ER, Yang J, So J, Fanti M, Leimgruber S, Kahn M, Ishitani T, Shin D, Mustata Wilson G, Monga SP. Identification and characterization of a novel small-molecule inhibitor of β-catenin signaling. Am J Pathol 184: 2111–2122, 2014. (Erratum. Am J Pathol 185: 2861, 2015). doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evanko SP, Potter-Perigo S, Bollyky PL, Nepom GT, Wight TN. Hyaluronan and versican in the control of human T-lymphocyte adhesion and migration. Matrix Biol 31: 90–100, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faggian J, Fosang AJ, Zieba M, Wallace MJ, Hooper SB. Changes in versican and chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans during structural development of the lung. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 293: R784–R792, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00801.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gill S, Wight TN, Frevert CW. Proteoglycans: key regulators of pulmonary inflammation and the innate immune response to lung infection. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 293: 968–981, 2010. doi: 10.1002/ar.21094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guarda G, Braun M, Staehli F, Tardivel A, Mattmann C, Förster I, Farlik M, Decker T, Du Pasquier RA, Romero P, Tschopp J. Type I interferon inhibits interleukin-1 production and inflammasome activation. Immunity 34: 213–223, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hillesheim A, Nordhoff C, Boergeling Y, Ludwig S, Wixler V. β-Catenin promotes the type I IFN synthesis and the IFN-dependent signaling response but is suppressed by influenza A virus-induced RIG-I/NF-κB signaling. Cell Commun Signal 12: 29, 2014. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-12-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirose J, Kawashima H, Yoshie O, Tashiro K, Miyasaka M. Versican interacts with chemokines and modulates cellular responses. J Biol Chem 276: 5228–5234, 2001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007542200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoebe K, Du X, Georgel P, Janssen E, Tabeta K, Kim SO, Goode J, Lin P, Mann N, Mudd S, Crozat K, Sovath S, Han J, Beutler B. Identification of Lps2 as a key transducer of MyD88-independent TIR signalling. Nature 424: 743–748, 2003. doi: 10.1038/nature01889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoebe K, Janssen EM, Kim SO, Alexopoulou L, Flavell RA, Han J, Beutler B. Upregulation of costimulatory molecules induced by lipopolysaccharide and double-stranded RNA occurs by Trif-dependent and Trif-independent pathways. Nat Immunol 4: 1223–1229, 2003. doi: 10.1038/ni1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoshino K, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Sanjo H, Ogawa T, Takeda Y, Takeda K, Akira S. Cutting edge: Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-deficient mice are hyporesponsive to lipopolysaccharide: evidence for TLR4 as the Lps gene product. J Immunol 162: 3749–3752, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang J, Olivenstein R, Taha R, Hamid Q, Ludwig M. Enhanced proteoglycan deposition in the airway wall of atopic asthmatics. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 160: 725–729, 1999. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.2.9809040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang SM, Mishina YM, Liu S, Cheung A, Stegmeier F, Michaud GA, Charlat O, Wiellette E, Zhang Y, Wiessner S, Hild M, Shi X, Wilson CJ, Mickanin C, Myer V, Fazal A, Tomlinson R, Serluca F, Shao W, Cheng H, Shultz M, Rau C, Schirle M, Schlegl J, Ghidelli S, Fawell S, Lu C, Curtis D, Kirschner MW, Lengauer C, Finan PM, Tallarico JA, Bouwmeester T, Porter JA, Bauer A, Cong F. Tankyrase inhibition stabilizes axin and antagonizes Wnt signalling. Nature 461: 614–620, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nature08356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hume DA. Applications of myeloid-specific promoters in transgenic mice support in vivo imaging and functional genomics but do not support the concept of distinct macrophage and dendritic cell lineages or roles in immunity. J Leukoc Biol 89: 525–538, 2011. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0810472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kagan JC. Defining the subcellular sites of innate immune signal transduction. Trends Immunol 33: 442–448, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kang I, Harten IA, Chang MY, Braun KR, Sheih A, Nivison MP, Johnson PY, Workman G, Kaber G, Evanko SP, Chan CK, Merrilees MJ, Ziegler SF, Kinsella MG, Frevert CW, Wight TN. Versican deficiency significantly reduces lung inflammatory response induced by polyinosine-polycytidylic acid stimulation. J Biol Chem 292: 51–63, 2017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.753186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kawai T, Adachi O, Ogawa T, Takeda K, Akira S. Unresponsiveness of MyD88-deficient mice to endotoxin. Immunity 11: 115–122, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawashima H, Atarashi K, Hirose M, Hirose J, Yamada S, Sugahara K, Miyasaka M. Oversulfated chondroitin/dermatan sulfates containing GlcAbeta1/IdoAalpha1-3GalNAc(4,6-O-disulfate) interact with L- and P-selectin and chemokines. J Biol Chem 277: 12921–12930, 2002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200396200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kawashima H, Hirose M, Hirose J, Nagakubo D, Plaas AH, Miyasaka M. Binding of a large chondroitin sulfate/dermatan sulfate proteoglycan, versican, to L-selectin, P-selectin, and CD44. J Biol Chem 275: 35448–35456, 2000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003387200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khare P, Bose A, Singh P, Singh S, Javed S, Jain SK, Singh O, Pal R. Gonadotropin and tumorigenesis: direct and indirect effects on inflammatory and immunosuppressive mediators and invasion. Mol Carcinog 56: 359–370, 2017. doi: 10.1002/mc.22499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim S, Takahashi H, Lin WW, Descargues P, Grivennikov S, Kim Y, Luo JL, Karin M. Carcinoma-produced factors activate myeloid cells through TLR2 to stimulate metastasis. Nature 457: 102–106, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nature07623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kolb JP, Casella CR, SenGupta S, Chilton PM, Mitchell TC. Type I interferon signaling contributes to the bias that Toll-like receptor 4 exhibits for signaling mediated by the adaptor protein TRIF. Sci Signal 7: ra108, 2014. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227: 680–685, 1970. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liang J, Zhang Y, Xie T, Liu N, Chen H, Geng Y, Kurkciyan A, Mena JM, Stripp BR, Jiang D, Noble PW. Hyaluronan and TLR4 promote surfactant-protein-C-positive alveolar progenitor cell renewal and prevent severe pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Nat Med 22: 1285–1293, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nm.4192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Masuda A, Yasuoka H, Satoh T, Okazaki Y, Yamaguchi Y, Kuwana M. Versican is upregulated in circulating monocytes in patients with systemic sclerosis and amplifies a CCL2-mediated pathogenic loop. Arthritis Res Ther 15: R74, 2013. doi: 10.1186/ar4251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Merrilees MJ, Ching PS, Beaumont B, Hinek A, Wight TN, Black PN. Changes in elastin, elastin binding protein and versican in alveoli in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res 9: 41, 2008. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-9-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Merrilees MJ, Hankin EJ, Black JL, Beaumont B. Matrix proteoglycans and remodelling of interstitial lung tissue in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. J Pathol 203: 653–660, 2004. doi: 10.1002/path.1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Merrilees MJ, Zuo N, Evanko SP, Day AJ, Wight TN. G1 domain of versican regulates hyaluronan organization and the phenotype of cultured human dermal fibroblasts. J Histochem Cytochem 64: 353–363, 2016. doi: 10.1369/0022155416643913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miyake Y, Kaise H, Isono K, Koseki H, Kohno K, Tanaka M. Protective role of macrophages in noninflammatory lung injury caused by selective ablation of alveolar epithelial type II Cells. J Immunol 178: 5001–5009, 2007. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.5001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mjaatvedt CH, Yamamura H, Capehart AA, Turner D, Markwald RR. The Cspg2 gene, disrupted in the hdf mutant, is required for right cardiac chamber and endocardial cushion formation. Dev Biol 202: 56–66, 1998. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morales MM, Pires-Neto RC, Inforsato N, Lanças T, da Silva LF, Saldiva PH, Mauad T, Carvalho CR, Amato MB, Dolhnikoff M. Small airway remodeling in acute respiratory distress syndrome: a study in autopsy lung tissue. Crit Care 15: R4, 2011. doi: 10.1186/cc9401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moresco EM, LaVine D, Beutler B. Toll-like receptors. Curr Biol 21: R488–R493, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Müller U, Steinhoff U, Reis LF, Hemmi S, Pavlovic J, Zinkernagel RM, Aguet M. Functional role of type I and type II interferons in antiviral defense. Science 264: 1918–1921, 1994. doi: 10.1126/science.8009221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Naso MF, Zimmermann DR, Iozzo RV. Characterization of the complete genomic structure of the human versican gene and functional analysis of its promoter. J Biol Chem 269: 32999–33008, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.O’Neill LA, Golenbock D, Bowie AG. The history of Toll-like receptors—redefining innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 13: 453–460, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nri3446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]