Abstract

DNA methylation of cytosine residues is a well-studied epigenetic change, which regulates gene transcription by altering accessibility for transcription factors. Hypoxia is a pervasive stimulus that affects many physiological processes. The circulatory and respiratory systems adapt to chronic sustained hypoxia, such as that encountered during a high-altitude sojourn. Many people living at sea level experience chronic intermittent hypoxia (IH) due to sleep apnea, which leads to cardiovascular and respiratory maladaptation. This article presents a brief update on emerging evidence suggesting that changes in DNA methylation contribute to pathologies caused by chronic IH and potentially mediate adaptations to chronic sustained hypoxia by affecting the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) signaling pathway.

Keywords: carotid body reflex, blood pressure, redox state, antioxidant enzyme, DNA methyl transferases

Introduction

Epigenetic changes are alterations in chromatin that regulate gene transcription by altering the accessibility of the DNA for transcription factors without changes in the coding sequence of DNA per se (9, 14, 50). Covalent modifications of DNA or histone proteins and expression of microRNAs are considered major epigenetic mechanisms (9, 19). DNA methylation is a well-studied epigenetic change, which is characterized by methylation of cytosine residues located immediately 5′ to guanine (known as CpG dinucleotides), often occurring in clusters in the promoter region of genes that are designated “CpG islands” (19, 29). In general, DNA hypermethylation leads to transcriptional repression, whereas hypomethylation causes transcriptional activation (6, 29). Hypoxia, which is characterized by reduced availability of oxygen (O2), is a pervasive stimulus that affects many physiological processes. Much attention has been focused on identifying genetic variants that affect the physiological adaptations and maladaptations to hypoxia in humans (27). Emerging evidence suggests a number of hypoxia-induced genes are epigenetically regulated. This article presents a brief summary of the experimental evidence implicating epigenetic changes by DNA methylation as one of the molecular mechanisms underlying adaptive and maladaptive responses to chronic sustained and intermittent hypoxia.

DNA Methylation and Adaptation to Chronic Sustained Hypoxia

According to a United Nations Environment Programs report, 12% of the human population lives in mountain regions and experience sustained hypoxia as a consequence of low barometric pressure at high altitude (28). Chronic sustained hypoxia initiates a series of physiological adaptations to maintain O2 homeostasis. Examples include increased red blood cell production, formation of new blood vessels, and metabolic reprogramming of cells, to name a few (43). The increased number of red blood cells improves O2 carrying capacity, whereas angiogenesis facilitates the transport of oxygenated blood to the tissues, and reorganization of metabolic machinery is required to reduce O2 consumption and maintain redox homeostasis under prolonged O2 deprivation. Many of the physiological responses to sustained hypoxia are mediated at the transcriptional level by the binding of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) to a hypoxia-response element (HRE) located near the target gene (49). The consensus HIF-1 binding site sequence 5′-RCGTG-3′ contains a CpG dinucleotide, suggesting that HIF-1-dependent gene regulation is inherently sensitive to cytosine methylation by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) (54).

EPO, which encodes erythropoietin, is one of the best characterized hypoxia-induced genes. Erythropoietin increases red blood cell proliferation by inhibiting apoptosis in erythroid progenitors (18), thereby allowing more cells to mature and increasing blood O2-carrying capacity during sustained hypoxia. The EPO gene promoter and 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) have been reported to comprise a CpG island, and methylation of the CpG island is negatively correlated with gene expression (56). Methylation represses the EPO gene in two ways: high-density methylation of the 5′-UTR recruits a methyl-CpG binding protein to the promoter, and methylation of CpGs in the proximal promoter blocks the DNA binding of nuclear proteins that mediate transcriptional activation.

Although Andeans, Tibetans, and Ethopians who live at high altitude all experience chronic hypoxia, only Andeans have increased hemoglobin (Hb) concentrations (2–4, 16). The higher Hb concentrations in Andeans are associated with a greater incidence of chronic mountain sickness (CMS). In Andeans, hypoxic exposure during the prenatal period is associated with pulmonary vascular dysfunction in early adulthood (20). EGLN1 encodes prolyl hydroxylase 2 (PHD2), which negatively regulates the stability of HIF-1α in an O2-dependent manner (44). EGLN1 has an upstream HRE that is sensitive to cytosine methylation (7). The promoter region of EPAS1, which encodes HIF-2α, is fully enveloped by a CpG island (25). Given that EGLN1 and EPAS1 have been implicated in human evolutionary adaptation to high altitude (51), whether cytosine methylation of EGLN1 or EPAS1 contributes to maladaptive responses to chronic hypoxia in the Andean population remains an interesting possibility.

DNA Methylation and Maladaptive Responses to Intermittent Hypoxia

Approximately 10% of individuals in industrialized societies living at sea level experience chronic intermittent hypoxia (IH) as a result of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), a highly prevalent respiratory disorder characterized by periodic cessation of breathing during sleep (39, 46). While many people living at high altitude adapt to sustained hypoxia, those experiencing IH exhibit maladaptations resulting in a variety of pathologies. Population-based studies have shown that OSA patients are prone to develop hypertension with a strong correlation between the frequency of apnea events and hypertension (26, 33, 57), (40). Rodents exposed to IH, simulating the O2 profiles observed during sleep in patients with OSA, exhibit increased sympathetic tone and hypertension (15, 24, 38, 53). Emerging evidence suggests that exaggerated reflexes arising from the carotid body (CB), which is the primary sensory organ for monitoring arterial blood O2 levels, drives the increased sympathetic tone and hypertension caused by IH (42). In addition to causing hypertension, IH-induced CB activation also leads to a high incidence of irregular breathing including central apnea events, thereby contributing to the progression of OSA (41).

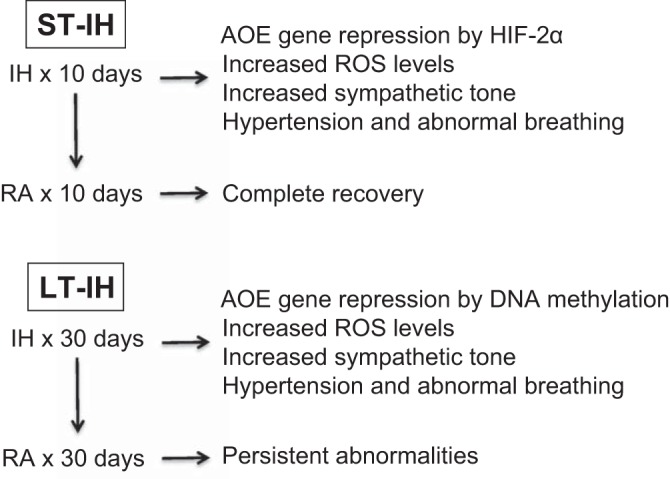

Reversal of autonomic changes triggered by the CB reflex in rodents critically depends on the duration of IH exposure (32). Short-term (10-day) exposure to IH (ST-IH) evoked an augmented CB reflex, but the increased sympathetic tone, hypertension, and irregular breathing were reversed by a 10-day recovery period in room air. In contrast, the effects of long-term (30-day) IH (LT-IH) on the CB reflex, hypertension, and irregular breathing persist even after a 30-day recovery period in room air (32). Although continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the first-line treatment for OSA, cardiorespiratory morbidities are not reversed by CPAP treatment in a subset of OSA patients (12, 30, 52) (13). The long-lasting autonomic morbidities caused by LT-IH suggest that long-term untreated OSA might lead to CPAP-resistant cardiorespiratory morbidities.

Oxidative stress resulting from increased levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is a major cellular mechanism underlying IH-evoked autonomic abnormalities (45). Increased ROS levels caused by ST-IH are mediated by HIF-1-dependent transcription of genes encoding prooxidant enzymes (such as Nox2, which encodes NADPH oxidase 2) and decreased HIF-2-dependent transcription of antioxidant enzyme (AOE) genes (37). Recovery in room air normalizes ROS levels after exposure of rats to ST-IH. In sharp contrast, LT-IH-evoked ROS levels remain elevated during room air recovery (32), indicating mechanisms other than acute transcriptional regulation contribute to long-lasting ROS generation by LT-IH.

Rats exposed to LT-IH exhibited increased DNA methylation and repression of several AOE genes including superoxide dismutase 1 and 2 (Sod1, Sod2), catalase (Cat), thioredoxin reductase 2 (Txnrd2), peroxiredoxin 4 (Prdx4), and glutathione peroxidase 2 (Gpx2) in the CB, adrenal medulla, and brainstem regions associated with the CB reflex (32). Bisulphite sequencing of the promoter region of the Sod2 gene showed methylation of a single CpG dinucleotide at +157 bp (relative to the transcription site), out of the 25 CpG sites analyzed (32).

LT-IH-evoked DNA methylation was tissue and cell selective and was not seen in brainstem regions that do not participate in the CB reflex (32). Brainstem regions that showed the absence of DNA methylation showed no changes in AOE gene expression or ROS levels in response to LT-IH (32). Unlike LT-IH, DNA methylation of AOE genes was not seen in rats exposed to ST-IH (32), indicating that prolonged exposure to IH is necessary to trigger DNA methylation.

DNMTs catalyze DNA cytosine methylation. Several DNMTs have been identified, including Dnmt1, Dnmt2, Dnmt3a, and Dnmt3b (5). While Dnmt1 is responsible for the maintenance of preexisting DNA methylation in cells, Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b are de novo methyltransferases (19). LT-IH-evoked DNA methylation was associated with increased expression of Dnmt1 and Dnmt3b proteins and elevated DNMT enzyme activity. Increased DNMT protein expression was due to posttranslational rather than transcriptional mechanisms (32). Treatment with decitabine, a DNA methylation inhibitor, either during LT-IH or during recovery from LT-IH, prevented DNA methylation; normalized the expression of AOE genes, ROS levels, CB chemosensory reflex, and blood pressure; and stabilized breathing (32). These observations suggest that LT-IH leads to long-lasting hypertension and breathing instability by causing oxidative stress in the CB reflex pathway through repression of AOE genes by DNA methylation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic presentation of the role of DNA methylation in causing persistent cardiorespiratory abnormalities by long-term intermittent hypoxia (LT-IH). ST-IH, short-term intermittent hypoxia; AOE, antioxidant enzyme; RA, room air; ROS, reactive oxygen species; HIF-2α, hypoxia-inducible factor-2α.

A recent study analyzed DNA methylation profiles in blood samples from OSA patients before and after CPAP treatment (8). Blood was collected from 15 adult patients before and 6 wk after starting CPAP treatment. Significant differences in DNA methylation before and after CPAP treatment were found in 1,847 regions of the genome. Differentially methylated regions were associated with immune responses, especially gene regulation by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs). Single-locus quantitative PCR analysis revealed that DNA methylation was increased at PPAR-response elements (PPAREs) of eight genes in the post-CPAP treatment samples’ suggesting that CPAP treatment leads to an increase in DNA methylation at PPAREs, possibly affecting binding of the PPAR-γ complex and downstream gene expression.

OSA also leads to selective activation of inflammatory response pathways (11). Several inflammatory factors, such as IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α, were found in high concentrations in the blood samples of subjects with OSA. It is likely that the high concentrations of these cytokines contribute to weight gain in patients with OSA. Cytokines are reported to be aberrantly regulated by multiple epigenetic mechanisms including DNA methylation, as well as covalent modification of histones and microRNA in the context of tumor pathogenesis and metabolic disorders (47, 55). Whether DNA methylation contributes to OSA-induced changes in inflammatory genes is not known.

Children with OSA manifest alterations in postocclusive hyperemia, a vascular response that is dependent on endothelial nitric oxide synthase (encoded by Nos2). OSA children with abnormal postocclusive hyperemia showed reduced Nos2 gene expression and methylation of a CpG site located at position −171 relative to the Nos2 transcription start site (22). DNA methylation of the FOXP3 gene, which regulates expression of regulatory T lymphocytes, was also found in children with OSA who exhibit increased systemic inflammatory responses (23).

Recurrent apnea with IH is also a major clinical problem in infants who are born preterm (1). Infants with apnea of prematurity often exhibit an augmented ventilatory response to hypoxia, a hallmark of the hyperactivity of the CB chemoreflex (1). A similar increase in CB chemoreflex activity was also seen in rat pups exposed to IH from postnatal days 0 to 10 (36). Unlike adult rats, the effects of neonatal IH were not normalized after recovery in room air for 10 days; rather they persisted into adulthood (35). Remarkably, adult rats that were exposed to IH as neonates showed irregular breathing with apneas and hypertension as adults (31), a finding reminiscent of clinical studies showing high incidence of sleep apnea and hypertension in young adults who were born preterm (10, 17, 34, 48). Adult rats that were exposed to IH as neonates showed repression of Sod2, and this effect was associated with DNA methylation of a single CpG dinucleotide close to the transcription start site (31). Treating neonatal rats with decitabine, an inhibitor of DNA methylation, during IH exposure prevented oxidative stress and autonomic dysfunction in adult life (31). These findings suggest that neonatal IH predisposes to autonomic dysfunction in adulthood through altered redox state caused by DNA methylation of AOE genes such as Sod2.

Pregnant women exhibit a relatively high prevalence of OSA during late gestation, and the resulting IH may affect the offspring’s somatic growth, energy homeostasis, and metabolic function. A recent study (21) showed that male but not female offspring from mice exposed to IH during late gestation showed higher body weights, food intake, adiposity index, fasting insulin, triglycerides and cholesterol levels, and these effects were associated with an increased number of proinflammatory macrophages in visceral white adipose tissue along with 1,520 differentially methylated gene regions associated with 693 genes. These findings indicate that perturbations to the fetal environment by OSA during pregnancy can trigger DNA methylation of genes, which may lead to persistent metabolic dysfunction in adulthood.

Perspectives

It appears from the above described studies that the role of DNA methylation in adaptation to chronic sustained hypoxia is relatively less well explored. People living at high altitude besides experiencing chronic hypoxia are also subjected to variations in environmental changes, nutritional status, infectious pathogens, pollutants, and cultural changes. Delineating the direct effects of hypoxia vs. indirect effects caused by other factors on DNA methylation in high altitude populations can be challenging. DNA methylation appears cell-type specific, which poses another challenge in human studies because sampling is usually limited to analysis of peripheral blood cells, which may or may not reflect systemic adaptations. Although emerging evidence suggests that DNA methylation contributes to maladaptive responses to chronic IH associated with sleep apnea in adults and neonates, the consequences of short- and long-term IH are complex and are regulated not only by altered expression of AOE genes in brainstem and CB but also by multiple pathways affecting a large number of genes in many different cell types. Consequently, further studies are needed to broadly assess DNA methylation of genes other than those associated with regulation of redox state, immunity, and inflammation in response to sustained hypoxia and chronic IH. Besides DNA methylation, histone modifications and microRNAs are other major epigenetic changes. Limited information is available on the roles of other epigenetic changes in mediating adaptive and maladaptive responses to chronic sustained hypoxia and IH.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant P01-HL-90554.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.N. and N.R.P. conceived and designed research; J.N. and N.R.P. performed experiments; J.N. and N.R.P. analyzed data; J.N. and N.R.P. interpreted results of experiments; J.N. and N.R.P. prepared figures; J.N. and N.R.P. drafted manuscript; J.N., G.L.S., and N.R.P. edited and revised manuscript; J.N., G.L.S., and N.R.P. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abu-Shaweesh JM, Martin RJ. Neonatal apnea: what’s new? Pediatr Pulmonol 43: 937–944, 2008. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beall CM, Brittenham GM, Strohl KP, Blangero J, Williams-Blangero S, Goldstein MC, Decker MJ, Vargas E, Villena M, Soria R, Alarcon AM, Gonzales C. Hemoglobin concentration of high-altitude Tibetans and Bolivian Aymara. Am J Phys Anthropol 106: 385–400, 1998. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beall CM, Cavalleri GL, Deng L, Elston RC, Gao Y, Knight J, Li C, Li JC, Liang Y, McCormack M, Montgomery HE, Pan H, Robbins PA, Shianna KV, Tam SC, Tsering N, Veeramah KR, Wang W, Wangdui P, Weale ME, Xu Y, Xu Z, Yang L, Zaman MJ, Zeng C, Zhang L, Zhang X, Zhaxi P, Zheng YT. Natural selection on EPAS1 (HIF2alpha) associated with low hemoglobin concentration in Tibetan highlanders. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 11459–11464, 2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002443107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beall CM, Decker MJ, Brittenham GM, Kushner I, Gebremedhin A, Strohl KP. An Ethiopian pattern of human adaptation to high-altitude hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 17215–17218, 2002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252649199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bird A. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev 16: 6–21, 2002. doi: 10.1101/gad.947102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bird AP, Wolffe AP. Methylation-induced repression–belts, braces, and chromatin. Cell 99: 451–454, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81532-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown CJ, Rupert JL. Hypoxia and environmental epigenetics. High Alt Med Biol 15: 323–330, 2014. doi: 10.1089/ham.2014.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cortese R, Zhang C, Bao R, Andrade J, Khalyfa A, Mokhlesi B, Gozal D. DNA methylation profiling of blood monocytes in patients with obesity hypoventilation syndrome: effect of positive airway pressure treatment. Chest 150: 91–101, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.02.648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cyr AR, Domann FE. The redox basis of epigenetic modifications: from mechanisms to functional consequences. Antioxid Redox Signal 15: 551–589, 2011. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalziel SR, Parag V, Rodgers A, Harding JE. Cardiovascular risk factors at age 30 following pre-term birth. Int J Epidemiol 36: 907–915, 2007. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Lima FF, Mazzotti DR, Tufik S, Bittencourt L. The role inflammatory response genes in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a review. Sleep Breath 20: 331–338, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s11325-015-1226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dudenbostel T, Calhoun DA. Resistant hypertension, obstructive sleep apnoea and aldosterone. J Hum Hypertens 26: 281–287, 2012. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2011.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eckert DJ, White DP, Jordan AS, Malhotra A, Wellman A. Defining phenotypic causes of obstructive sleep apnea. Identification of novel therapeutic targets. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 188: 996–1004, 2013. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201303-0448OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feinberg AP. Phenotypic plasticity and the epigenetics of human disease. Nature 447: 433–440, 2007. doi: 10.1038/nature05919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fletcher EC. An animal model of the relationship between systemic hypertension and repetitive episodic hypoxia as seen in sleep apnoea. J Sleep Res 4, S1: 71–77, 1995. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1995.tb00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garruto RM, Dutt JS. Lack of prominent compensatory polycythemia in traditional native Andeans living at 4,200 meters. Am J Phys Anthropol 61: 355–366, 1983. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330610310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hibbs AM, Johnson NL, Rosen CL, Kirchner HL, Martin R, Storfer-Isser A, Redline S. Prenatal and neonatal risk factors for sleep disordered breathing in school-aged children born preterm. J Pediatr 153: 176–182, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jelkmann W. Molecular biology of erythropoietin. Intern Med 43: 649–659, 2004. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.43.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin B, Li Y, Robertson KD. DNA methylation: superior or subordinate in the epigenetic hierarchy? Genes Cancer 2: 607–617, 2011. doi: 10.1177/1947601910393957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Julian CG, Gonzales M, Rodriguez A, Bellido D, Salmon CS, Ladenburger A, Reardon L, Vargas E, Moore LG. Perinatal hypoxia increases susceptibility to high-altitude polycythemia and attendant pulmonary vascular dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 309: H565–H573, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00296.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khalyfa A, Cortese R, Qiao Z, Ye H, Bao R, Andrade J, Gozal D. Late gestational intermittent hypoxia induces metabolic and epigenetic changes in male adult offspring mice. J Physiol 595: 2551–2568, 2017. doi: 10.1113/JP273570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kheirandish-Gozal L, Khalyfa A, Gozal D, Bhattacharjee R, Wang Y. Endothelial dysfunction in children with obstructive sleep apnea is associated with epigenetic changes in the eNOS gene. Chest 143: 971–977, 2013. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim J, Bhattacharjee R, Khalyfa A, Kheirandish-Gozal L, Capdevila OS, Wang Y, Gozal D. DNA methylation in inflammatory genes among children with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 185: 330–338, 2012. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201106-1026OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar GK, Rai V, Sharma SD, Ramakrishnan DP, Peng YJ, Souvannakitti D, Prabhakar NR. Chronic intermittent hypoxia induces hypoxia-evoked catecholamine efflux in adult rat adrenal medulla via oxidative stress. J Physiol 575: 229–239, 2006. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.112524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lachance G, Uniacke J, Audas TE, Holterman CE, Franovic A, Payette J, Lee S. DNMT3a epigenetic program regulates the HIF-2α oxygen-sensing pathway and the cellular response to hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 7783–7788, 2014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322909111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lavie P, Herer P, Hoffstein V. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome as a risk factor for hypertension: population study. BMJ 320: 479–482, 2000. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7233.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacInnis MJ, Koehle MS, Rupert JL. Evidence for a genetic basis for altitude illness: 2010 update. High Alt Med Biol 11: 349–368, 2010. doi: 10.1089/ham.2010.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Millet GP, Roels B, Schmitt L, Woorons X, Richalet JP. Combining hypoxic methods for peak performance. Sports Med 40: 1–25, 2010. doi: 10.2165/11317920-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miranda TB, Jones PA. DNA methylation: the nuts and bolts of repression. J Cell Physiol 213: 384–390, 2007. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mulgrew AT, Lawati NA, Ayas NT, Fox N, Hamilton P, Cortes L, Ryan CF. Residual sleep apnea on polysomnography after 3 months of CPAP therapy: clinical implications, predictors and patterns. Sleep Med 11: 119–125, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nanduri J, Makarenko V, Reddy VD, Yuan G, Pawar A, Wang N, Khan SA, Zhang X, Kinsman B, Peng YJ, Kumar GK, Fox AP, Godley LA, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Epigenetic regulation of hypoxic sensing disrupts cardiorespiratory homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 2515–2520, 2012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120600109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nanduri J, Peng YJ, Wang N, Khan SA, Semenza GL, Kumar GK, Prabhakar NR. Epigenetic regulation of redox state mediates persistent cardiorespiratory abnormalities after long-term intermittent hypoxia. J Physiol 595: 63–77, 2017. doi: 10.1113/JP272346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nieto FJ, Young TB, Lind BK, Shahar E, Samet JM, Redline S, D’Agostino RB, Newman AB, Lebowitz MD, Pickering TG. Association of sleep-disordered breathing, sleep apnea, and hypertension in a large community-based study. Sleep Heart Health Study. JAMA 283: 1829–1836, 2000. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.14.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paavonen EJ, Strang-Karlsson S, Räikkönen K, Heinonen K, Pesonen AK, Hovi P, Andersson S, Järvenpää AL, Eriksson JG, Kajantie E. Very low birth weight increases risk for sleep-disordered breathing in young adulthood: the Helsinki Study of Very Low Birth Weight Adults. Pediatrics 120: 778–784, 2007. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pawar A, Peng YJ, Jacono FJ, Prabhakar NR. Comparative analysis of neonatal and adult rat carotid body responses to chronic intermittent hypoxia. J Appl Physiol (1985) 104: 1287–1294, 2008. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00644.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peng YJ, Rennison J, Prabhakar NR. Intermittent hypoxia augments carotid body and ventilatory response to hypoxia in neonatal rat pups. J Appl Physiol (1985) 97: 2020–2025, 2004. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00876.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peng YJ, Yuan G, Khan S, Nanduri J, Makarenko VV, Reddy VD, Vasavda C, Kumar GK, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-α isoforms and redox state by carotid body neural activity in rats. J Physiol 592: 3841–3858, 2014. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.273789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peng YJ, Yuan G, Ramakrishnan D, Sharma SD, Bosch-Marce M, Kumar GK, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Heterozygous HIF-1alpha deficiency impairs carotid body-mediated systemic responses and reactive oxygen species generation in mice exposed to intermittent hypoxia. J Physiol 577: 705–716, 2006. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.114033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, Palta M, Hagen EW, Hla KM. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol 177: 1006–1014, 2013. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med 342: 1378–1384, 2000. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005113421901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prabhakar NR. Oxygen sensing during intermittent hypoxia: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Appl Physiol (1985) 90: 1986–1994, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prabhakar NR, Peng YJ, Kumar GK, Nanduri J. Peripheral chemoreception and arterial pressure responses to intermittent hypoxia. Compr Physiol 5: 561–577, 2015. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prabhakar NR, Semenza GL. Adaptive and maladaptive cardiorespiratory responses to continuous and intermittent hypoxia mediated by hypoxia-inducible factors 1 and 2. Physiol Rev 92: 967–1003, 2012. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prabhakar NR, Semenza GL. Gaseous messengers in oxygen sensing. J Mol Med (Berl) 90: 265–272, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s00109-012-0876-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prabhakar NR, Semenza GL. Regulation of carotid body oxygen sensing by hypoxia-inducible factors. Pflugers Arch 33: N61–7, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s00424-015-1719-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Punjabi NM. The epidemiology of adult obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc 5: 136–143, 2008. doi: 10.1513/pats.200709-155MG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raghuraman S, Donkin I, Versteyhe S, Barrès R, Simar D. The emerging role of epigenetics in inflammation and immunometabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab 27: 782–795, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosen CL, Larkin EK, Kirchner HL, Emancipator JL, Bivins SF, Surovec SA, Martin RJ, Redline S. Prevalence and risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing in 8- to 11-year-old children: association with race and prematurity. J Pediatr 142: 383–389, 2003. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2003.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factors in physiology and medicine. Cell 148: 399–408, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sharma S, Kelly TK, Jones PA. Epigenetics in cancer. Carcinogenesis 31: 27–36, 2010. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simonson TS, Yang Y, Huff CD, Yun H, Qin G, Witherspoon DJ, Bai Z, Lorenzo FR, Xing J, Jorde LB, Prchal JT, Ge R. Genetic evidence for high-altitude adaptation in Tibet. Science 329: 72–75, 2010. doi: 10.1126/science.1189406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thomas RJ, Terzano MG, Parrino L, Weiss JW. Obstructive sleep-disordered breathing with a dominant cyclic alternating pattern--a recognizable polysomnographic variant with practical clinical implications. Sleep 27: 229–234, 2004. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Troncoso Brindeiro CM, da Silva AQ, Allahdadi KJ, Youngblood V, Kanagy NL. Reactive oxygen species contribute to sleep apnea-induced hypertension in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H2971–H2976, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00219.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wenger RH, Stiehl DP, Camenisch G. Integration of oxygen signaling at the consensus HRE. Sci STKE 2005: re12, 2005. doi: 10.1126/stke.3062005re12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yasmin R, Siraj S, Hassan A, Khan AR, Abbasi R, Ahmad N. Epigenetic regulation of inflammatory cytokines and associated genes in human malignancies. Mediators Inflamm 2015: 201703, 2015. doi: 10.1155/2015/201703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yin H, Blanchard KL. DNA methylation represses the expression of the human erythropoietin gene by two different mechanisms. Blood 95: 111–119, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Young T, Peppard P, Palta M, Hla KM, Finn L, Morgan B, Skatrud J. Population-based study of sleep-disordered breathing as a risk factor for hypertension. Arch Intern Med 157: 1746–1752, 1997. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1997.00440360178019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]