Over the past several decades, numerous control systems models have been devised to simulate the known kinematic features of saccades in normal primates. These models have proven valuable to neurophysiology, as a means of generating testable predictions. The present manuscript, as far as we are aware, is the first to present control systems models to simulate the known abnormalities of saccades in strabismus.

Keywords: model, neurophysiology, pattern strabismus, saccade, strabismus

Abstract

In pattern strabismus the horizontal and vertical misalignments vary with eye position along the orthogonal axis. The disorder is typically described in terms of overaction or underaction of oblique muscles. Recent behavioral studies in humans and monkeys, however, have reported that such actions are insufficient to fully explain the patterns of directional and amplitude disconjugacy of saccades. There is mounting evidence that the oculomotor abnormalities associated with strabismus are at least partially attributable to neurophysiological abnormalities. A number of control systems models have been developed to simulate the kinematic characteristics of saccades in normal primates. In the present study we sought to determine whether these models could simulate the abnormalities of saccades in strabismus by making two assumptions: 1) in strabismus the burst generator gains differ for the two eyes and 2) abnormal crosstalk exists between the horizontal and vertical saccadic circuits in the brain stem. We tested three models, distinguished by the location of the horizontal-vertical crosstalk. All three models were able to simulate amplitude and directional saccade disconjugacy, postsaccadic drift, and a pattern strabismus for static fixation, but they made different predictions about the dynamics of saccades. By assuming that crosstalk occurs at multiple nodes, the Distributed Crosstalk Model correctly predicted the dynamics of saccades. These new models make additional predictions that can be tested with future neurophysiological experiments.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Over the past several decades, numerous control systems models have been devised to simulate the known kinematic features of saccades in normal primates. These models have proven valuable to neurophysiology, as a means of generating testable predictions. The present manuscript, as far as we are aware, is the first to present control systems models to simulate the known abnormalities of saccades in strabismus.

INTRODUCTION

For the development and maintenance of binocular vision the eyes must remain aligned so that objects of interest activate the foveae of both eyes. For ~3–4% of children, however, the eyes are chronically misaligned, a condition referred to as strabismus (Lorenz 2002). This disorder can be associated with abnormalities of eye muscles, orbital connective tissues (Kono et al. 2008; Stager et al. 2013), and/or impaired development of neural pathways (for recent reviews see Das 2016; Walton et al. 2017), but in many cases the cause is unknown. When they occur in infancy during a sensitive period of postnatal development, the above etiological factors interfere with binocular vision and lead to a permanent strabismus (Das 2016; Walton et al. 2017). Indeed, rearing infant monkeys with prism goggles or alternating monocular occlusion is sufficient to induce a permanent strabismus, with associated impairments of binocular responses in visual cortex (Tusa et al. 2002; Tychsen 2007; Tychsen et al. 2008). Infantile strabismus also leads to numerous oculomotor abnormalities, including latent nystagmus (Mustari et al. 2001; Tusa et al. 2001; Tusa et al. 2002; Tychsen and Boothe 1996) asymmetrical smooth pursuit gain (Mustari and Ono 2011; Mustari et al. 2008; Tychsen et al. 1985), saccade disconjugacy (Bucci et al. 2002; Fu et al. 2007; Kapoula et al. 1997; Maxwell et al. 1995; Walton et al. 2014), and an absence of disparity vergence (Kenyon et al. 1981).

In recent years, a number of studies have used nonhuman primate models of infantile strabismus to link these behavioral deficits to neurophysiological abnormalities. Although strabismus can be associated with abnormalities of the muscles and/or plant, the existing evidence from nonhuman primate models is sufficient to rule out the hypothesis that these oculomotor symptoms are due solely to peripheral abnormalities (for recent reviews see Das 2016; Walton et al. 2017).

Numerous studies have demonstrated abnormalities in visual cortical areas of monkeys with strabismus induced in infancy (two recent reviews: Das 2016; Walton et al. 2017). It is not known whether these visual abnormalities differ, depending on how the strabismus was induced. The details of how visual cortical abnormalities might lead to disrupted signaling in oculomotor systems are also unknown, but the reviews cited above consider what is known.

In pattern strabismus, the horizontal and vertical misalignments vary with eye position along the orthogonal axis. The cause is often assumed to be overaction or underaction of the oblique muscles (Kekunnaya et al. 2015; Knapp 1959), but this clinical description does not address the important issue of why these particular muscles would be overactive or underactive (for a clinical discussion, see Wright and Strube 2012). More importantly, it does not address evidence that abnormal signals are sent to the medial rectus and vertical rectus muscles in pattern strabismus (Das and Mustari 2007; Joshi and Das 2011).

From a modeling standpoint, one of the biggest challenges is how to simulate the observation that saccade direction can differ for the two eyes in pattern strabismus (Ghasia et al. 2015; Walton et al. 2014). Several authors have suggested the possibility that pattern strabismus may be associated with abnormal crosstalk between horizontal and vertical oculomotor signals in the brain stem (Das 2012; Ghasia et al. 2015; Walton and Mustari 2015; Walton et al. 2013). Numerous lines of evidence support this possibility. First, recent studies have demonstrated that, in both humans (Ghasia et al. 2015) and monkeys (Walton et al. 2014), saccade directional disconjugacy is consistent with the “A” or “V” patterns observed for static fixation. If horizontal and vertical velocity signals are inappropriately mixed, the mathematical integration of these “contaminated” signals, within monocularly organized circuits, could lead to “A” or “V” patterns of static fixation. Importantly, in both of these recent behavioral studies, the authors reported a pattern of saccade disconjugacy that could not be fully explained by oblique muscle overaction or underaction. For example, Ghasia et al. (2015) showed that directional saccade disconjugacy in human patients was not correlated with abnormal torsion, as it should have been if the phenomenon was entirely attributable to abnormal oblique muscle action. Thus some other phenomenon must be at work here. Second, in monkeys with experimentally induced strabismus, microstimulation of most sites in pontine paramedian reticular formation (PPRF) evokes movements with short-latency, disconjugate vertical components (Walton et al. 2013). Third, single unit recordings in PPRF of strabismic monkeys have revealed an abnormally broad distribution of preferred directions on one side of the brain (i.e., left or right PPRF) (Walton and Mustari 2015). This may indicate the presence of an asymmetrical vertical input to the horizontal brain stem saccadic pathway. Finally, many humans and monkeys with strabismus are able to fixate visual targets with either eye, and frequently switch between the two (Agaoglu et al. 2014; Sireteanu 1982; Steinbach 1981; van Leeuwen et al. 2001). In monkeys with pattern strabismus, near-response cell activity was related to changes in horizontal strabismus angle associated with alternation of the fixating eye, but was not predictive of variations in horizontal misalignment associated with “A” or “V” patterns (Das 2011, 2012). The author suggested that variations in horizontal strabismus angle that were not accounted for by near-response cell modulation might be the result of abnormal crosstalk between horizontal and vertical pathways in the brain stem.

There may well be abnormal action of oblique muscles in pattern strabismus but the above evidence, taken together, strongly suggests that this disorder is associated with abnormal crosstalk between horizontal and vertical oculomotor pathways in the brain stem. The nature of this hypothetical crosstalk is unknown, however. The primary goal of the present study was to test three different models, that vary with respect to the nature and/or placement of the horizontal-vertical crosstalk, to determine which ones could simulate the amplitude, directional, and dynamic disconjugacies of saccades in pattern strabismus. All three models employed separate burst generators for the two eyes, abnormal horizontal-vertical interactions, and mismatched connection weights. It is worth noting that monocular burst generators have been proposed as a mechanism to account for disjunctive saccades that accompany vergence in normal primates (King and Zhou 2002).

A secondary interest was the question of whether these models could produce the horizontal and vertical static misalignments characteristic of pattern strabismus, even in the absence of abnormalities of eye muscles or the plant (for a recent review that discusses mechanical factors in more detail see Das 2016). Importantly, the purpose here was not to dispute the well-established fact that peripheral abnormalities can be important etiological factors in strabismus. However, it is clear from the existing literature that infantile strabismus is associated with abnormalities in brain stem oculomotor structures (two recent reviews: Das 2016; Walton et al. 2017). The present study attempts to determine whether directional saccade disconjugacy could be simulated by models that assume abnormal crosstalk between horizontal and vertical brain stem pathways.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and Surgical Procedures

The models were developed using a previously published data set (Walton et al. 2014). The models made different predictions regarding the dynamic changes in directional disconjugacy during saccades. These predictions were tested by collecting new data sets from five monkeys (Normal: N1 and N2; Strabismic: ET1, ET2, XT1).

All experimental procedures complied with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research, and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Washington National Primate Research Center. Five rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) served as subjects. Monkeys N1 and N2 had normal eye alignment. Monkey ET1 had incomitant esotropia (typically ~15°, but it could range from 25° to 2° of exotropia). For the first 3 mo of life this animal wore prism goggles (right eye: 20 prism diopter, base-in; left eye: 20 prism diopter, base-down). Monkey ET2 also had incomitant esotropia, with a highly variable horizontal misalignment that typically ranged from 10° to 30°. This animal received two injections of botulinum toxin (2.5 U/0.1 ml; 0.2 ml/injection) into the lateral rectus muscle during the first 6 mo of life, with two more follow-up injections at 1 and 2 yr of age. Monkey XT1 underwent a bilateral medial rectus tenotomy, performed during the first week of life. This resulted in a persistent “A” pattern exotropia (typically ~25° when fixating with the right eye and ~35° to 40° when fixating with the left eye). Following these procedures the animals were allowed to reach maturity without further intervention. After they had reached maturity, all animals underwent two surgeries to implant head posts, recording chambers, and eye coils underneath the conjunctiva of both eyes (Fuchs and Robinson 1966; Judge et al. 1980). Further details of these procedures can be found in our previously published work (Mustari et al. 2001; Ono and Mustari 2007). Monkeys ET1, N1, and XT1 are the same three animals used in our 2014 behavioral study but, as noted above, new data sets were used for dynamic analyses.

Behavioral Tasks and Visual Display

Our behavioral task and display system were identical to what we described in our previously published behavioral study (Walton et al. 2014). Briefly, animals sat in a primate chair, with their heads stabilized, during each recording session. Targets consisted of red, 0.25° laser spots, back projected onto a tangent screen that was positioned 57 cm from the animal’s eyes. The positions of both eyes were measured using the magnetic search coil technique (Fuchs and Robinson 1966; Judge et al. 1980), with a sampling rate of 1 kHz. Calibration of the eye coil signals was performed separately for each eye, under monocular viewing conditions, while the animal fixated static targets that stepped from −20° to 20°, in 5° steps, horizontally and vertically.

Monkeys received a small liquid or food reward every 300 ms, if at least one eye was directed within 5° of the target. Animals fixated each target for 1.5 to 5 s, after which it stepped to another, randomly chosen, location. Target positions were chosen by randomly selecting the horizontal and vertical coordinates (−20° to 20°, in 5° increments). Thus target steps could be up to 40° horizontally and/or vertically. In monkeys ET1 and ET2 monocular viewing was achieved either by patching one eye, or with a set of liquid crystal shutter goggles (Micron Technology, Boise, ID) that permitted monocular or binocular viewing. Monkey XT1 had difficulty seeing targets presented in the contralateral hemifield when the goggles were used. Without them, she consistently used the left eye to fixate targets to the left of straight ahead, and the right eye to fixate targets >15° to the right. Between these points she alternated frequently. Due to her large exotropia, however, the fellow eye was always 25° to 40° away from the target.

Data Analysis

Spike 2 and a CED 1401 (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK) were used for data acquisition. Offline data analyses were conducted in Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA) using custom functions.

Saccade onset was defined as the first point in time at which both velocity and acceleration exceeded threshold values (50°/s and 10,000°/s2, respectively). Saccade offset was defined as the first time point at which either of two conditions were met: 1) eye velocity below 50°/s and 2) absolute value of acceleration was less than 10,000°/s2. These criteria successfully excluded postsaccadic drifts (Walton et al. 2014). This algorithm was validated based on single unit recordings of medium lead burst neurons in PPRF (Walton and Mustari 2015); these cells evince a consistent relationship between burst duration and saccade duration (Hepp and Henn 1983; Keller 1974; Luschei and Fuchs 1972).

Models

The models were implemented in Simulink (Mathworks). As is the case for many models of the normally functioning saccadic system (Becker and Jürgens 1990; Freedman 2001; Walton et al. 2005), a vectorial saccadic command is decomposed into horizontal and vertical components to comport with the requirements imposed by the arrangement of extraocular muscles. As with most control systems models of the saccadic system, a local feedback loop is assumed, in which a resettable (i.e., after each saccade) integrator supplies a dynamic estimate of current displacement to a comparator.

All three models assume that SC is monocular. In two of the models, the Feedback Loop Crosstalk Model and the Integrator Crosstalk Model, the motor maps for the two eyes are anatomically aligned. Mature subjects with strabismus that originated in infancy typically do not experience diplopia because visual perception in the nonviewing eye is suppressed (Von Noorden and Campos 2002). For this reason, these two models assume that the output of SC, for a particular saccade, will be a single desired displacement command, appropriate for the eye that is to be brought to the target. Nonetheless, the assumption of a monocular SC is not crucial to these two models since the neural basis of saccade disconjugacy is downstream. In our tests, both models produced identical results if one assumes, instead, a binocular SC that drives monocular premotor burst neurons.

The three models were implemented as follows:

Feedback Loop Crosstalk Model.

This model assumes that the neural basis for directional saccade disconjugacy lies within the local feedback loop that is believed to control saccade amplitudes. In most control systems models of the normal saccadic system, a feedback signal related to current eye displacement is subtracted from a desired displacement command. When the difference between the two reaches zero, the movement ends.

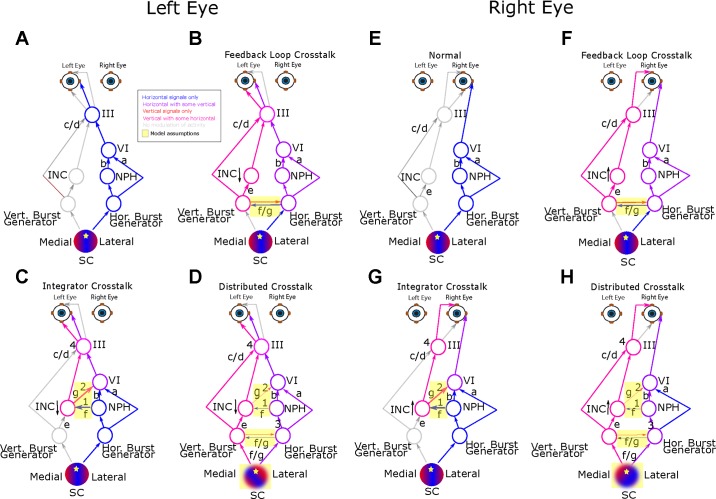

The Feedback Loop Crosstalk Model incorporates monocular directional crosstalk at the level of saccadic premotor structures (horizontal red and blue arrows labeled “f/g” in Fig. 1, B and F). More specifically, the signed output of the vertical burst generator is added (with reduced gain) to the monocular output of the horizontal burst generator. Similarly, the signed output of the horizontal burst generator is subtracted from the monocular output of the vertical burst generator. Importantly, this crosstalk affects the monocular current displacement command within the local feedback loop. For each saccade, there is a single desired displacement command, appropriate for the eye that is to be directed to the target. We assumed that the saccade ends for both eyes when, and only when, the dynamic motor error for the viewing eye reaches zero. This is equivalent to assuming that the omnipause neurons gate both eyes in the same way. As with all three models, a simple switch determines which eye should be brought to the target.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the models, all of which assume a monocular saccadic system in strabismus. In the interest of clarity the circuit is depicted separately for the left eye (A–D) and right eye (E–H). The downward (B–D) and upward (F–H) arrows near crosstalk elements indicate that the crosstalk affects premotor circuitry with different on-directions for the left and right eyes. Lowercase letters a–e correspond to the similarly labeled values in Table 1, and represent sites at which gain differences between the two eyes influence amplitude disconjugacy; lowercase letters f and g correspond to crosstalk elements responsible for directional disconjugacy (yellow rectangles are used to further highlight these crosstalk elements). A and E: simplified schematic showing the normal activation of brain stem saccade circuitry driving a horizontal saccade. Because the output command from SC represents a purely horizontal desired displacement, the vertical saccadic pathway is shown in gray. B and F: Feedback Loop Crosstalk Model. SC is assumed to be normal. Sections of the motor map that encode horizontal saccades are shown in blue. Circuitry associated with vertical saccades is shown in magenta, to emphasize the abnormal influence of horizontal signals via the crosstalk. Because of the abnormal crosstalk between the horizontal and vertical burst generators, different vertical saccadic commands are introduced to riMLF for the two eyes. The downstream circuitry is normal, but inherits the altered command. Downstream horizontal pathways are shown in purple instead of blue to represent the abnormal influence of vertical commands. C and G: the superior colliculus and the burst generators are assumed to be effectively normal. Crosstalk is assumed to affect burst-tonic neurons in the horizontal (NPH) and vertical (INC) neural integrators. Specifically, we hypothesize that anatomical connections that are present (but maybe functionally weak) in normal monkeys are abnormally strong in pattern strabismus. Arrows labeled “1” (Belknap and McCrea 1988) and “2” (Graf et al. 2002; Ugolini et al. 2006) refer to the relevant neuroanatomical studies. D and H: the Distributed Crosstalk Model assumes a more general breakdown of directional tuning that affects multiple nodes within the saccadic system. The crosstalk at any one node is relatively weak, but the cumulative effect is a cascade of abnormalities that causes saccade-related neurons in numerous brain stem areas to carry faulty directional signals. Note that, in all three models, the crosstalk would cause the saccades to be inaccurate were it not for saccadic adaptation which, in adult monkeys with strabismus, is conjugate (Das et al. 2004). Thus directional saccadic adaptation corrects the directional error for the viewing eye, but exacerbates it for the fellow eye.

Integrator Crosstalk Model.

This model assumes that abnormal crosstalk occurs downstream from the local feedback loop. This is equivalent to assuming that copies of the horizontal and vertical bursts are sent to the orthogonal neural integrators (possibly motoneurons serving eye muscles with orthogonal pulling directions as well). This model assumes that the crosstalk affects burst-tonic neural integrator neurons but not the upstream premotor burst neurons.

A projection from nucleus prepositus hypoglossi (NPH) to the interstitial nucleus of Cajal (INC) is schematically represented as a blue arrow with a “1” above it in Fig. 1, C and G (Belknap and McCrea 1988). A projection from INC to abducens nucleus is represented by a pink arrow with a “2” above it (Graf et al. 2002; Ugolini et al. 2006). In Fig. 1 these two connections (elements “f” and “g”) form the basis of the horizontal-vertical and vertical-horizontal crosstalk, respectively. In our testing, however, the models showed equivalent performance if one assumes other connections between burst-tonic neural integrator neurons and motoneurons serving eye muscles with orthogonal pulling directions (for example, between burst-tonic INC neurons and medial rectus motoneurons). In our model, the signed output of the vertical burst generator is subtracted (with reduced gain) from the monocular output of the horizontal burst generator. Similarly, the signed output of the horizontal burst generator is subtracted from the monocular output of the vertical burst generator. The resulting directionally disconjugate saccadic commands are then passed through monocular neural integrators (Sylvestre et al. 2003).

Distributed Crosstalk Model.

This model assumes that the neural basis of pattern strabismus is the result of a widespread disruption of directional tuning in brain stem oculomotor structures. This model postulates that, in early postnatal life, abnormal monocular signals in visual cortex influence the development of motor maps in the intermediate layers of superior colliculus (SC), causing them to be monocular, and mildly distorted in ways that differ for the two eyes (schematically illustrated as fuzzy, distorted red and blue coloring of the circle representing SC in Fig. 1, D and H). For example, in pattern strabismus, a disproportionately large region of the map would encode vectors with an upward component for one eye, while vectors with a downward component would be overrepresented for the other eye. For a given saccade, a single SC site is activated, but the decomposition of this vectorial signal into horizontal and vertical components differs for the two eyes. In addition, the absolute value of vertical velocity is subtracted from the horizontal velocity signal (for the nonviewing eye) within the local feedback loop. Finally, the model also employs the same crosstalk element that characterizes the Integrator Crosstalk Model. Importantly, however, the gain of each of these crosstalk elements is relatively low; directional disconjugacy results from the accumulation of small directional disconjugacies throughout the circuit (i.e., lines representing hypothesized crosstalk are thin in Fig. 1, D and H).

To simulate the origin of disconjugate saccadic commands, all three models assume a monocularly organized saccadic system in strabismus. Many previously published models assume that the saccadic system is binocularly organized in normal primates (Busettini and Mays 2005; Zee et al. 1992). However, a monocularly organized saccadic system has been suggested to simulate disjunctive saccades that accompany vergence in normal primates (King and Zhou 2002). In their model the burst generators for the two eyes are driven by separate, monocular error signals. The Feedback Loop Crosstalk Model and the Integrator Crosstalk Model differ from theirs in that the input to the burst generators is assumed to be a single desired displacement command, appropriate for the eye that is to be directed to the target. This assumption was motivated, in part, by our PPRF stimulation data in strabismic animals (Walton et al. 2013) which, presumably, would input an identical command to the assumed monocular burst neurons for both eyes.

In all three of these models, saccade amplitude disconjugacy results from different gains for the two eyes at the level of projections to the neural integrators and motoneurons. For all models, the burst generator gains were based on experimentally derived component amplitude ratios (AmpLeft/AmpRight) for real saccades between targets that stepped along the cardinal axes in two monkeys with experimentally induced pattern strabismus (Walton et al. 2014).

To simulate the known characteristics of directional saccade disconjugacy, all three models employ abnormalities that adjust the horizontal and vertical component amplitudes for the nonviewing eye as a linear function of the amplitudes of both components for the viewing eye. Mathematically, this can be described using the following equation:

| (1) |

Suppose, for example, the right eye (viewing) makes a horizontal saccade, 10° to the right. In this case, one can use Eq. 1 to compute the left (fellow) eye’s vertical component as follows:

Since there is no vertical component for the viewing (right) eye, the value of the first term is simply 0. This gives: VertAmpFellow = b × 10. If b (the horizontal-to-vertical crosstalk gain) is −0.3, then the nonviewing (left) eye will have a downward component of 3°.

The models were developed using a large sample of real saccades obtained from two strabismic monkeys for a previously published behavioral study (Walton et al. 2014). This previously published data set included saccades with amplitudes ranging from 1° to 46°, in all directions, from an esotrope (ET1; n = 13,965) and an exotrope (XT1; n = 8,799). Both of these animals had pattern strabismus. Detailed descriptions of the relevant behavioral characteristics can be found in our previously published work (Walton and Mustari 2015; Walton et al. 2014). As we note in these earlier studies, the method of inducing strabismus differed in the two animals (monkey ET1: prism rearing for the first 3 mo of life; monkey XT1: bilateral medial rectus tenotomy during the first week of life). Both approaches have been used extensively to create nonhuman primate models of infantile strabismus. What these methods have in common is that retinal correspondence is prevented during a sensitive period early in life, which results in a chronic impairment of binocular visual responses (Kiorpes 2015; Kiorpes et al. 1996; Mustari et al. 2008; Tychsen 2007). For this reason, it is likely that the visual cortical abnormalities are similar for monkeys with strabismus induced in infancy, regardless of the method of induction. To our knowledge, however, this question has not been systematically explored. A more detailed discussion of this issue is available in two recently published review articles (Das 2016; Walton et al. 2017).

As noted above, we have previously analyzed saccades across a wide range of amplitudes and directions in monkeys with pattern strabismus (Walton et al. 2014). A major goal of the present study was to determine whether physiologically plausible modifications to models of the normal saccadic system could simulate the patterns of disconjugacy we reported in that study. To provide a comparable data set, therefore, each model was run 2,000 times, with randomly selected horizontal and vertical desired displacements (ranging from −20° to 20°, in 1° increments). The simulated saccade data were then analyzed using the same saccade detection algorithm and Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA) data analysis functions used by Walton et al. (2014) to analyze real saccades from strabismic monkeys. For example, we computed the polar direction for each eye, for each saccade. Data were then placed into 30° bins with respect to the viewing eye’s saccade direction. For a given saccade, the data for both eyes were included in the same bin regardless of the direction for the nonviewing eye. For each bin the horizontal, vertical, and vectorial amplitudes were compared between the two eyes using the same equations used to describe the disconjugacy of real saccades in these same two strabismic monkeys (Eq. 1; see also Walton et al. 2014).

The difference in saccade direction for the two eyes was computed using the following equation:

DirectionDifference is simplified to the range of ± 180° to avoid ambiguity. Similarly, we computed the horizontal and vertical amplitude disconjugacies using the following equation:

For example, consider an oblique saccade of (8°, 2°) for left eye and (10°, −2°) for the right eye. This would yield a ComponentAmpDisconjHor of −2° and ComponentAmpDisconjVert of 4°.

To repeat the analyses shown in figures 6–8 of Walton et al. (2014), we computed averaged saccade vectors for each eye for amplitude-matched simulated saccades in various directions. We first identified all saccades for which the right eye’s vectorial amplitude was between 8° and 12°. For each direction bin averaged saccade vectors were computed for each eye. Statistical tests are described under the relevant subheadings in results.

For half of the simulations for each model, the initial positions of the two eyes were set to simulate 20° of exotropia, with a 10° vertical strabismus angle. The gain values for the projections from the burst generators to motoneurons and integrators were the same for all models except for the Distributed Crosstalk Model, and were set based on the typical amplitude disconjugacy for an exotropic monkey we have used in several recent studies (monkey XT1, Fleuriet et al. 2016; Walton and Mustari 2015; Walton et al. 2013, 2014). For the other half of the simulations for each model, the initial eye positions were set to simulate 15° of esotropia, with a 10° vertical strabismus angle. For these simulations, gain values were based on the behavioral data for an esotropic monkey we have used in several recent studies (monkey ET1, Fleuriet et al. 2016; Walton and Mustari 2015; Walton et al. 2013, 2014). For this animal, the amplitude disconjugacy of upward saccades differed from that of downward saccades. Therefore, we assigned different gain values for premotor bursts for upward vs. downward saccades. Gain values for both sets of simulations are shown in Table 1. The physiological plausibility of these assumptions is considered in discussion.

Table 1.

Gain values for various nodes in the Feedback Loop Crosstalk Model, Integrator Crosstalk Model, and Distributed Crosstalk Model

| Horizontal Pulse (a) | Horizontal Integrator (b) | Vertical Pulse, Up (c) | Vertical Pulse, Down (d) | Vertical Integrator (e) | Horizontal-Vertical Crosstalk (f) | Vertical-Horizontal Crosstalk (g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feedback Loop Crosstalk Model, and Integrator Crosstalk Model | |||||||

| Esotropia simulations | 1.12 | 0.93 | 1.14 | 0.97 | 0.85 | 0.05 | 0.15 |

| Exotropia simulations | 0.75 | 0.93 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.85 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| Distributed Crosstalk Model | |||||||

| Esotropia simulations | 1.12 | 0.93 | 1.14 | 0.97 | 0.85 | 0.03; 0; 0.01 | 0.10; 0.15; 0.10 |

| Exotropia simulations | 0.75 | 0.93 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.85 | 0.20; 0; 0.15 | 0.20; 0.15; 0.15 |

Lowercase letters a–g correspond to the similarly labeled elements in Fig. 1. For the Distributed Crosstalk Model, several crosstalk gain values are given for the horizontal and vertical pathways. In order, they correspond to crosstalk upstream from, within, and downstream from the local feedback loop, respectively.

Quantitative Comparison of Simulated and Real Saccades

For each model, we compared the mean component amplitude ratios for each direction bin to the value obtained for the corresponding direction bin for the behavioral data. For this analysis, the horizontal and vertical amplitude ratios were pooled to obtain a single R2 value for each model that quantifies the similarity between simulated and real saccades.

RESULTS

General Characteristics of Strabismus in Monkeys ET1, ET2, and XT1

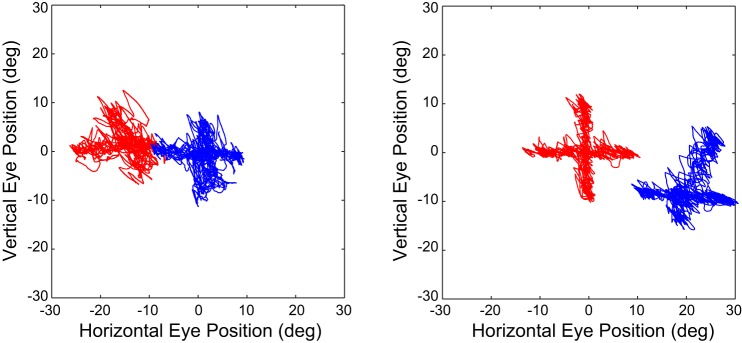

Our algorithm detected 39,348 saccades, including 22,389 from monkey ET1, 10,033 from monkey ET2, 9,032 from monkey XT1, 15,613 from monkey N1, and 7,927 from monkey N2. It should be noted, however, that our data acquisition system records eye position continuously, rather than dividing the experiment into discrete trials. For this reason, our algorithm detected many small saccades that were less than 5° in amplitude, that were not analyzed further. These included goal-directed saccades in response to small target steps, fixational saccades, corrective saccades, and nystagmus quick phases (monkey ET2). In addition, we distinguished between “left-eye viewing,” “right-eye viewing,” “left-right fixation switching,” and “right-left fixation switching” based on which eye was on target before the target step and which eye was on target after the saccade. This means that some accurate, target-directed saccades were excluded from analysis because neither eye was on target at the time the target stepped. This happened if the monkey momentarily looked away, or was in the process of switching the fixating eye at the time of the target step. In these situations, we could not confidently assign the saccade to any of those four “eye fixation” categories, so these movements were excluded. For monkey N1, 5,097 saccades met the inclusion criteria (see materials and methods) for the analysis of saccade curvature. There were 1,631 saccades for monkey N2, 4,858 for monkey ET1, 1,848 for monkey ET2, and 2,118 for monkey XT1. A detailed description of the strabismus in monkeys ET1 and XT1 is available in our previously published behavioral study, which employed the same animals (Walton et al. 2014). Hess screen charts for monkeys ET1 and XT1 are shown in figure 1 of this previous study. To illustrate the pattern strabismus in monkey ET2, Fig. 2 shows a Hess screen chart, based on 7–9 cycles of horizontal and vertical sinusoidal smooth pursuit (0.15 Hz) with each eye fixating. This esotropic monkey showed a strong pattern strabismus.

Fig. 2.

Hess screen plots for monkey ET2, based on horizontal and vertical smooth pursuit tracking. Blue = left eye; red = right eye. A: left-eye viewing. B: right-eye viewing.

Behavior

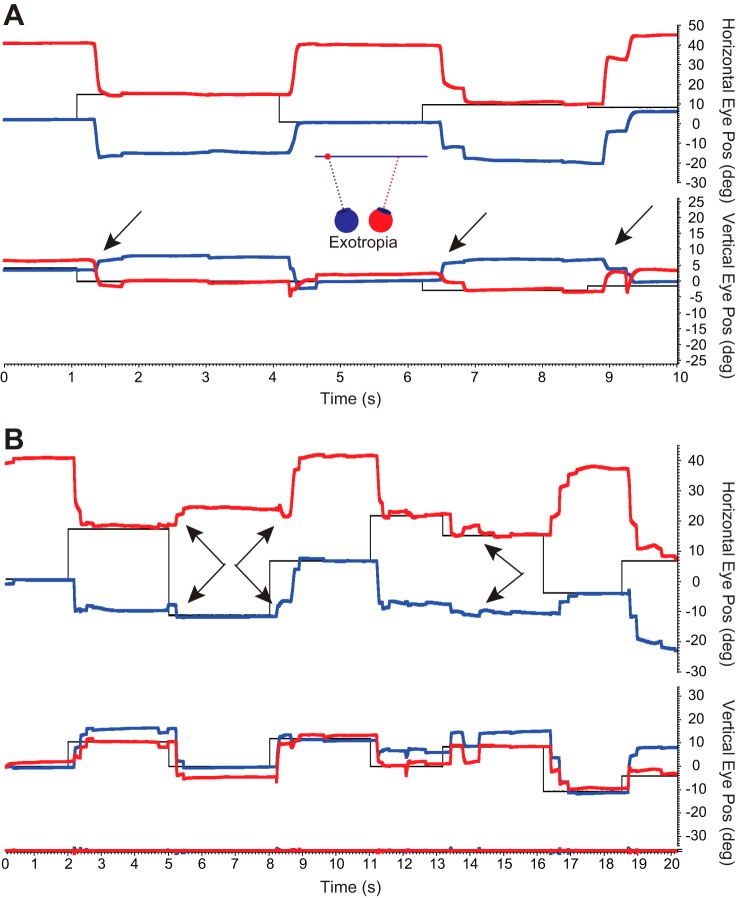

Figure 3 shows example raw behavioral data from monkey XT1. Arrows identify oblique saccades for which the smaller component was in opposite directions for the two eyes. Note that the opposite-direction component could be either vertical (Fig. 3A) or horizontal (Fig. 3B). This phenomenon was also observed for esotropic monkey ET1, although less consistently. Figure 4 shows two examples of raw data from monkey ET1 in which the vertical (Fig. 4A) or horizontal (Fig. 4B) component is in opposite directions for the two eyes (arrows).

Fig. 3.

Example abnormal saccades in exotropic monkey XT1. A: arrows indicate several oblique saccades for which the smaller (vertical) component is in opposite directions for the two eyes. Note that two of the fixation switching saccades are hypometric and are followed closely by corrective saccades. B: oblique saccades for which the horizontal component is in opposite directions for the two eyes (arrows). Note that the occurrence of opposite direction components could occur either in association with large saccades to a peripheral target or smaller saccades made to targets near the central visual field of the nonviewing eye. Several fixation-switching saccades can be seen in both panels.

Fig. 4.

Example abnormal saccades in esotropic monkey ET1. A: arrows indicate several oblique saccades for which the smaller (vertical) component is in opposite directions for the two eyes. B: a series of oblique saccades that occurred when the animal made a series of saccades away from the target. Arrows indicate four saccades for which the horizontal component was in opposite directions for the two eyes. Note that the vertical axis has a limited range in the top half of B. This was done to allow the reader to more easily see the detail of the abnormal horizontal components.

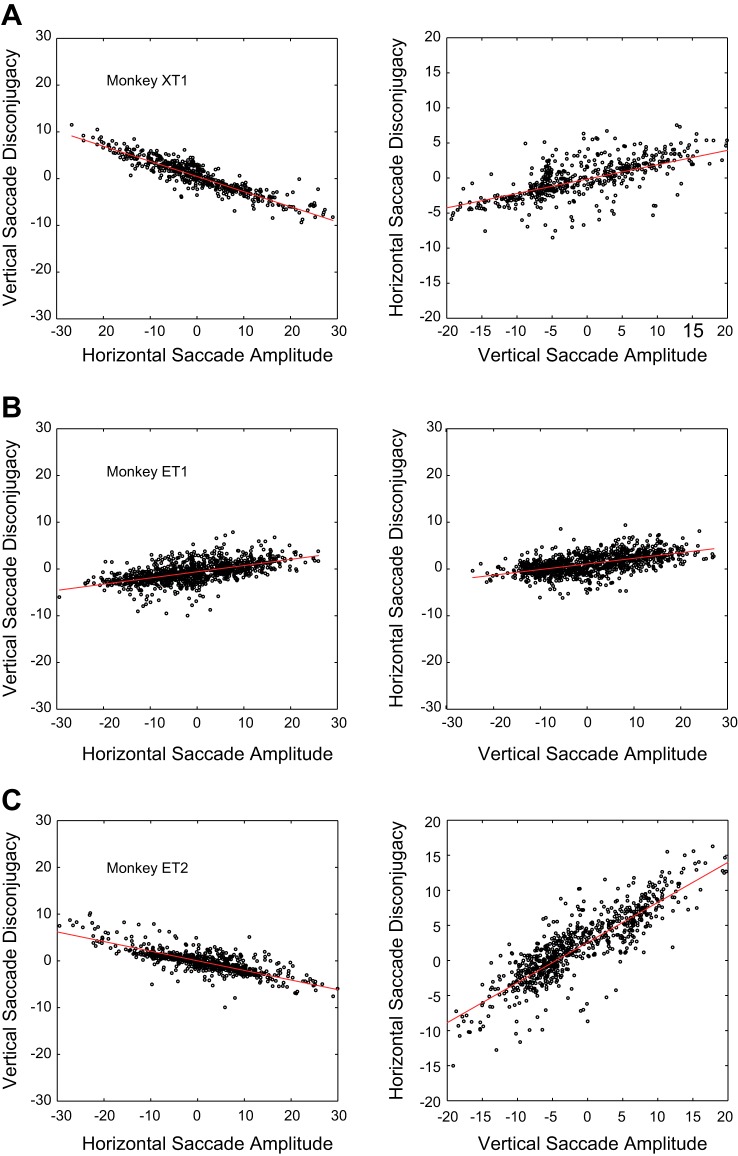

We wondered whether such movements were a specific instance of a more general effect. As noted in the introduction, we were interested in the possibility that directional disconjugacy is due to abnormal crosstalk between horizontal and vertical brain stem circuits. For this reason, it is of particular interest to determine whether a relatively simple mathematical description could be applied to the horizontal and vertical disconjugacies (see materials and methods) of saccades of many amplitudes and directions. Figure 5 shows this analysis for one example recording session in monkey XT1 (Fig. 5A), one in monkey ET1 (Fig. 5B) and one in monkey ET2 (Fig. 5C). The left column plots vertical disconjugacy as a function of the horizontal amplitude; the right column plots horizontal disconjugacy as a function of vertical amplitude. When we performed this analysis on the data set as a whole the 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the slopes did not include 0 for horizontal or vertical disconjugacy, for any of the three strabismic monkeys [monkey XT1: horizontal disconjugacy vs. vertical amplitude, R2 = 0.39, slope = −0.31, 95% CI = −0.32 to −0.30; vertical disconjugacy vs. horizontal amplitude, R2 = 0.64, slope = −0.415, 95% CI = −0.42 to −0.41; monkey ET1: horizontal disconjugacy vs. vertical amplitude, R2 = 0.13, slope = 0.127, 95% CI = 0.122 to 0.132; vertical disconjugacy vs. horizontal amplitude, R2 = 0.03, slope = 0.03, 95% CI = 0.029 to 0.034; but was much stronger in monkey XT1, who exhibited a much stronger “A” pattern (see figure 1 of Walton et al. 2014); monkey ET2: horizontal disconjugacy vs. vertical amplitude, R2 = 0.63, slope = 0.541, 95% CI = 0.529 to 0.554; vertical disconjugacy vs. horizontal amplitude, R2 = 0.52, slope = −0.227, 95% CI = −0.234 to −0.221].

Fig. 5.

Relationship between horizontal and vertical saccade disconjugacy and the amplitude of the orthogonal component for saccades collected during a single experimental session, for each of the three strabismic animals. A: monkey XT1. B: monkey ET1. C: monkey ET2. Left column = vertical disconjugacy, plotted as a function of horizontal component amplitude. Right column = horizontal disconjugacy, plotted as a function of vertical component amplitude. For this figure, data were pooled across saccades made with the left-eye and right-eye viewing.

Model Simulations

We first sought to determine whether the models could simulate known saccade abnormalities in the monkeys used to develop the models (ET1 and XT1). Figure 6 shows simulated oblique saccades generated by each of the three models in response to the same desired displacement (20°, 3°). This vector was chosen with the goal of determining whether the models could simulate saccades with opposite-direction vertical components. As expected, all models produced saccades with amplitude disconjugacies. When the model settings were based on the component amplitude ratios from monkey XT1 (see figures 3 and 4 in Walton et al. 2014), vectorial amplitude was significantly different between the two eyes (paired t-test; Bonferroni correction) for all direction bins for all models, with the exception of 270° for the Integrator Crosstalk Model (P = 0.25). When the model settings were based on values derived from monkey ET1, vectorial amplitude was significantly different between the two eyes (paired t-test; Bonferroni correction) for all direction bins for all models, with the following exceptions: Integrator Crosstalk Model, 60° (P = 0.002), 240°, (P = 0.01); Feedback Loop Crosstalk Model, 60° (P = 0.58), 150° (P = 0.12).

Fig. 6.

Three example oblique simulated saccades, in response to a desired displacement (20°, 3°). The right eye is considered to be the viewing eye in these examples. For all three models, the vertical component is in opposite directions for the two eyes. In each case, the left (nonviewing) eye shows a downshoot, although it is notably smaller for the Feedback Loop Crosstalk Model (B) than for the other two models. The insets in A and B reveal a phenomenon that was not observed for the Integrator Crosstalk Model (C); the direction of the left eye’s vertical component sometimes reverses toward the end of the movement.

When the crosstalk gain settings were set to values estimated directly from the behavior (see above), all three models were able to produce simulated oblique saccades for which the smaller component was in opposite directions. When the larger component was horizontal there was a consistent downshoot for the adducting eye. This is characteristic of saccades in human subjects with A-pattern strabismus (Ghasia et al. 2015). Note, however, that the downshoot for the left eye was very small for the Feedback Loop Crosstalk Model (Fig. 6B). This occurred because the local feedback loop attempted to correct for the introduction of an inappropriate downward signal. In Fig. 6, A and B, toward the end of the movement, one can see a very small reversal in the direction of the vertical component for the left (nonviewing) eye (insets). This phenomenon was not observed for the Integrator Crosstalk Model. Similar reversals for the smaller component were sometimes observed in the behavioral data for both of our strabismic animals (see Figs. 3 and 4). Thus Fig. 6 shows that all three models can produce simulated oblique saccades for which the smaller component is in opposite directions for the two eyes. Importantly, however, the three models do not generate identical movements.

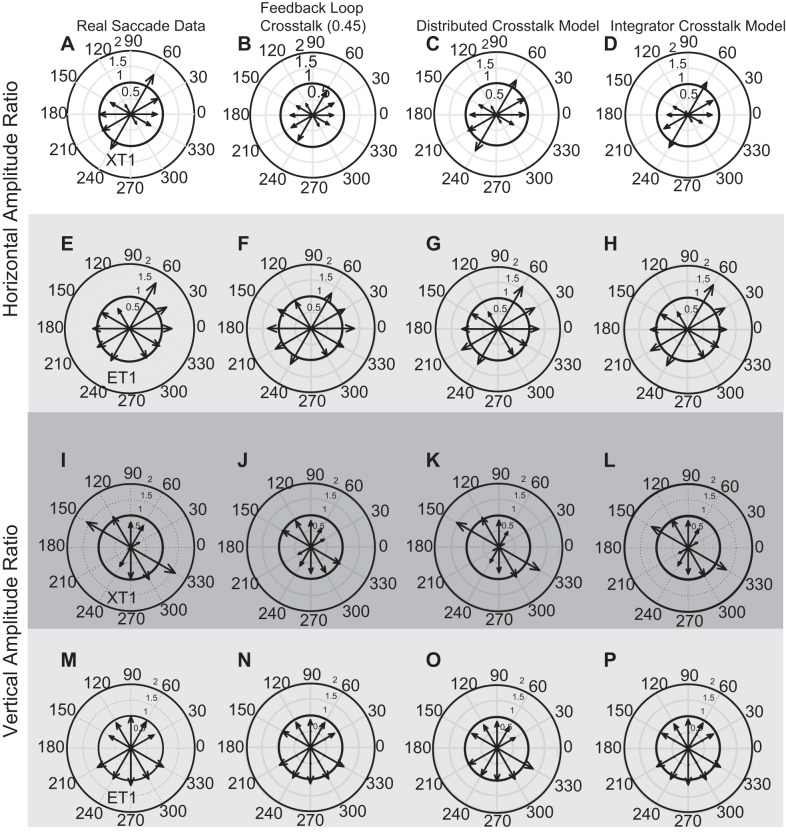

We next computed the horizontal and vertical component amplitude ratios for each model for the full data set. Figure 7 shows these data for simulated saccades generated by each of the three models, and compares these values to those obtained for real saccades in our previously published behavioral study (Walton et al. 2014). For a normal monkey, saccade amplitudes are nearly identical for the two eyes for saccades in all directions, which would yield a value very close to 1 (see figures 5A and 5B in Walton et al. 2014). For strabismic animals, however, the amplitudes are not the same, which yields values > 1 (left eye amplitude is larger) or < 1 (right eye amplitude is larger).

Fig. 7.

Horizontal (A–H) and vertical (I–P) amplitude ratios for saccades in various directions. The left column shows data obtained from exotropic monkey XT1 (A and I) and from esotropic monkey ET1 (E and M). Each row compares the behavioral data (far left panel) to the corresponding plots derived from each of the three models. A–D compare the horizontal amplitude ratios for monkey XT1 to simulated saccades generated by the models. In A (horizontal amplitude ratios, monkey XT1), E (horizontal amplitude ratios, monkey ET1), and I (vertical amplitude ratios, monkey XT1), note that the measured amplitude ratio varies systematically with the amplitude of the orthogonal component. Note also that the Feedback Loop Crosstalk Model (2nd column) failed to consistently simulate this pattern in the behavioral data (in particular, compare E and F).

To quantify the comparisons shown in Fig. 7 we computed a mean error for each model as follows:

where CA(n) refers to a component amplitude ratio for a given direction (e.g., the horizontal amplitude ratio for the 30° bin). The value in the denominator reflects the fact that component amplitude ratios were computed for each of 10 different direction bins, for both the horizontal and vertical components. The results of this analysis for monkey ET1 were as follows: Feedback Loop Crosstalk Model = 0.129; Distributed Crosstalk Model = 0.118; Integrator Crosstalk Model = 0.072. For monkey XT1 the results were: Feedback Loop Crosstalk Model = 0.194; Distributed Crosstalk Model = 0.075; Integrator Crosstalk Model = 0.094. Thus, although the initial parameter estimates were derived from the behavior, the three models did not simulate the data from the real animals equally well. This is because it matters where one places the crosstalk.

Despite the relatively poor performance of the Feedback Loop Crosstalk Model, one should be cautious about rejecting it based solely on the analyses reported above. It may simply be that the crosstalk gains were too low because the comparator actively opposes directional deviations that result from abnormal crosstalk within the local feedback loop. For example, subtracting a signal related to vertical velocity from the horizontal current displacement command for one eye would cause the comparator to attempt to compensate by increasing the drive to the horizontal pathway (presumably EBNs). This would mean that the “true” crosstalk gains cannot be estimated directly from behavior, due to the opposing action of the local feedback loop. With this concern in mind, we reran the simulations for this model, increasing the crosstalk gain values in increments of 0.10 until the slope of this relationship was as close to 1 as possible. Using this procedure we obtained optimal crosstalk gain values of 0.9 (XT1) and 0.6 (ET1). The corresponding ModelError values were 0.126 for monkey XT1 and 0.112 for monkey ET1. Note that, even with these new parameter estimates, the Feedback Loop Crosstalk Model did not simulate the behavioral data as well as the other models.

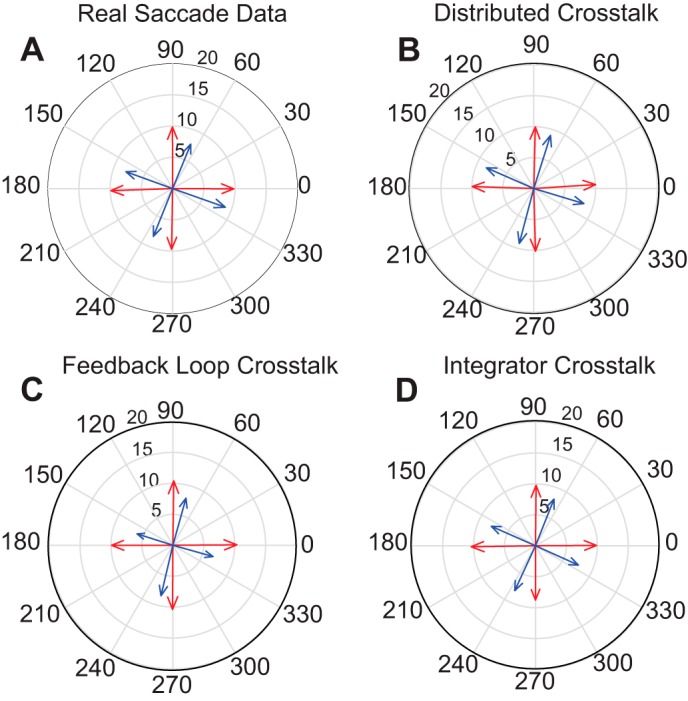

Directional Disconjugacy

Figure 8 plots averaged saccade vectors for each eye for four different direction bins for monkey XT1 and for each model. Figure 8A shows data for trials when the right eye was fixating the target. Note that the left eye’s direction is consistently deviated clockwise by almost 30°. Figure 8, B–D, shows data from simulated saccades, binned with respect to the right eye. For the Distributed Crosstalk Model (Fig. 8B) and the Integrator Crosstalk Model (Fig. 8D) the simulated data are very similar to the real data (Fig. 8A), in terms of both the amplitude and directional disconjugacy. For the Feedback Loop Crosstalk Model with the original crosstalk gain values (Fig. 8C), the directional disconjugacy was smaller than for the real data. For monkey ET1 saccade direction differed markedly for the two eyes for upward saccades (Fig. 9A). This was also true for the simulated data in Fig. 9, B and D. For the Feedback Loop Crosstalk Model, the directional disconjugacy of upward saccades was quite small when the same crosstalk gain was used (Fig. 9C).

Fig. 8.

Comparison of averaged vectors for the two eyes for monkey XT1 and model simulations. Data are based on 8°–12° saccades in 4 different directions. Blue = left eye; red = right eye. A shows data from monkey XT1. For saccades in all directions, the right eye’s saccade is deviated 15°–20° counterclockwise with respect to the direction of the left eye’s saccade. A similar effect can be seen in the model simulations (B–D).

Fig. 9.

Comparison of averaged vectors for the two eyes for monkey ET1 and model simulations. All conventions are the same as in Fig. 8. For real saccades (A) direction differs for the two eyes for upward saccades. When the same crosstalk values were used for all models, the Distributed Crosstalk Model (B) and the Integrator Crosstalk Model (D) were able to replicate this effect, but the Feedback Loop Crosstalk Model (C) did not.

For the behavioral data, the mean directional disconjugacies were −28.5° for monkey XT1 and −9.2° for monkey ET1. For the Feedback Loop Crosstalk Model the mean directional disconjugacies were −10.5° for monkey XT1 and −1.3° for monkey ET1. As noted above, this model was able to produce saccades with directional disconjugacies similar to what we observed for the other models (XT1, −21.5; ET1, −6.3) when we greatly increased the gain of the crosstalk. For the Integrator Crosstalk Model the mean directional disconjugacies were −26.3° for monkey XT1 and −6.0° for monkey ET1. For monkey XT1 the directional disconjugacy of simulated saccades was highly significant for all bins for all models (Watson-Williams test: P < 0.001). For monkey ET1, the direction of the simulated movements differed for the two eyes for the 30°, 60°, 90° bins for the Integrator Crosstalk Model and the Distributed Crosstalk Model. In addition, the directional disconjugacy reached significance for two other bins (240° for the Integrator Crosstalk Model and 0° for the Distributed Crosstalk Model). For the Feedback Loop Crosstalk Model with the original crosstalk gain values, the mean saccade direction differed for the two eyes only for the 90° bin. With a crosstalk gain of 0.6, saccade direction differed significantly for the two eyes for the 30°, 60°, 90° bins (P < 0.01).

Initial Eye Position

Before moving on to dynamic analyses, we first consider whether saccade disconjugacy might vary with respect to the initial orbital positions of the eyes. To investigate this issue we fit the data with modified versions of Eq. 1:

where IEPHor and IEPVert represent the horizontal and vertical eye positions at the time of saccade onset. This analysis was performed separately for every combination of viewing eye (right eye or left eye), prediction of component disconjugacy (horizontal or vertical), and the eye used in the IEP terms (right eye or left eye). This yielded a total of eight combinations for each of our strabismic monkeys. For this analysis we also included new data from a third strabismic monkey (ET2). This yielded a total of 24 model fits across the three monkeys.

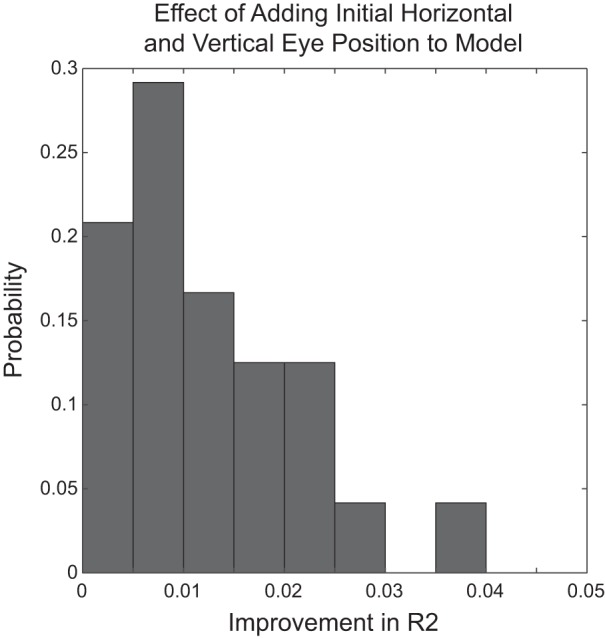

Figure 10 shows the results of this analysis. Note that the addition of terms related to horizontal and vertical initial eye position never improved the R2 value by more than 0.04 for any of these eight analyses, for any of our strabismic subjects. Thus initial eye position had little or no influence on horizontal or vertical saccade disconjugacy.

Fig. 10.

Effect of adding terms related to horizontal and vertical initial eye position to the model-predicting component amplitude disconjugacy. This was done separately for horizontal and vertical disconjugacy, right and left eye initial eye position, and for each viewing eye. This yielded 8 model fits for each of the 3 monkeys. The histogram shows the distribution of improvements in R2 values resulting from adding initial eye position terms to the model, across these 24 data points. Note that adding both initial eye position terms (horizontal and vertical) to the model never improved the R2 by more than 0.04.

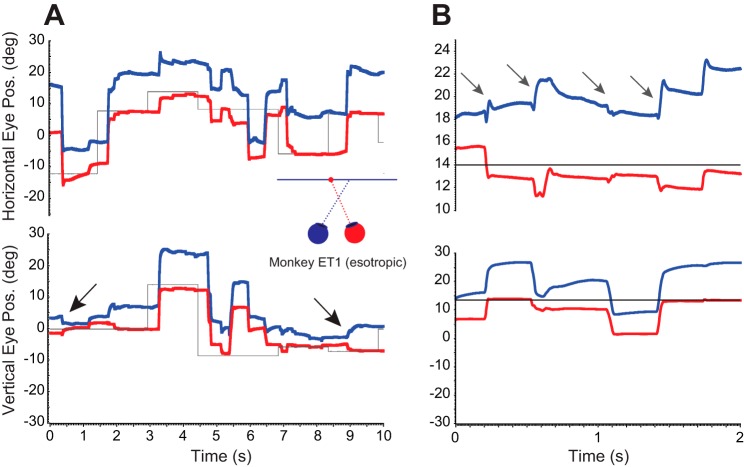

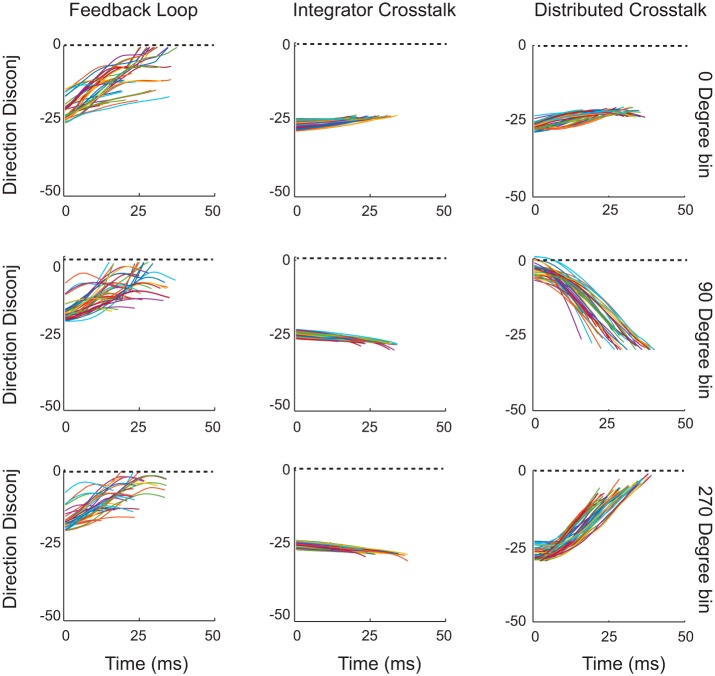

Dynamics of Saccade Disconjugacy

Up to this point we have only considered whether the models could simulate the patterns of saccade disconjugacy we have reported in a previous behavioral study (Walton et al. 2014). These analyses only considered static parameters such as amplitude ratios and the overall saccade direction. The crosstalk gains were initially selected based on the relationships between horizontal and vertical saccade disconjugacy and the amplitude of the orthogonal component (Fig. 5). Because pattern strabismus is highly variable between subjects (Wright and Strube 2012) the crosstalk gains will be different for each subject. In the implementation of these models, however, the crosstalk takes the form of continuous, dynamic signals. Thus a more robust test of the models would be to consider the dynamics of directional disconjugacy. To test the differential predictions of the models we collected new saccade data sets from monkeys ET1 and XT1, and a third strabismic monkey (ET2) that was not used to develop the models. We also collected new data from two normal controls, monkeys N1 and N2.

With these considerations in mind we computed, for each saccade, the instantaneous difference in saccade direction. Because the resulting traces were noisy for the behavioral data, however, we computed a 10-point moving average using the following equation:

where DD(t) is the smoothed directional disconjugacy at time t, and D(t)Left and D(t)Right are the instantaneous saccade directions for the left and right eye, respectively. This is a lot of smoothing, given the relatively short duration of saccades, but it is sufficient for our purpose, which was to get a general sense of how directional disconjugacy changes during the course of a saccade. Note that negative values of DD(t) indicate that the left eye’s direction is deviated in a clockwise deviation, relative to the right eye’s direction. This relates to an “A” pattern but does not necessarily represent exotropia.

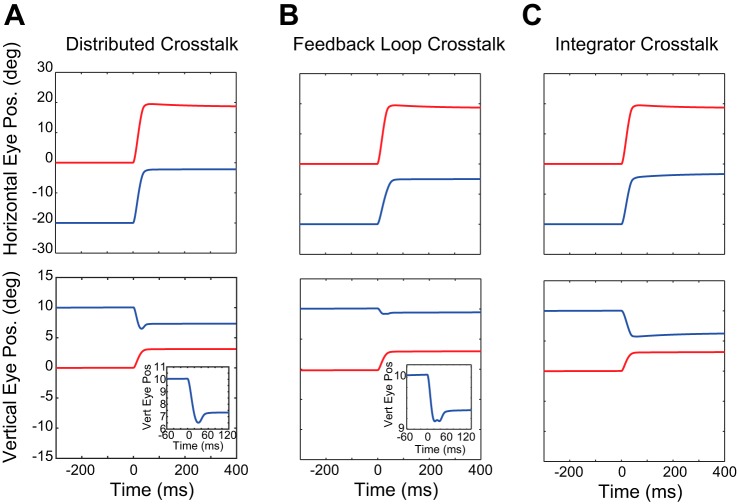

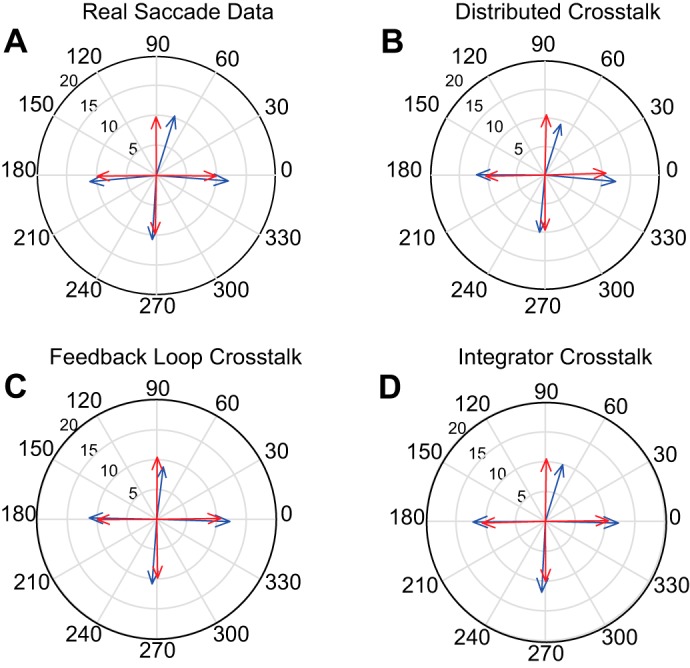

Figure 11 plots the directional disconjugacy, DD(t), as a function of time for simulated saccades in three different directions, for each of the three models. The Feedback Loop Crosstalk Model places a horizontal-vertical crosstalk within the local feedback loop. Because there is a single desired displacement command for both eyes, the comparator actively opposes the introduction of the inappropriate cross-axis signal. For this reason, the instantaneous directional disconjugacy becomes less severe as the saccade progresses. For the Integrator Crosstalk Model there is a single desired displacement command (for a given saccade) and the only crosstalk is downstream from the local feedback loop. For this reason, there is no dynamic compensation for the inappropriate signal and so the dynamic disconjugacy remains mostly constant. Finally, the Distributed Crosstalk Model assumes that a signal related to the vertical component of the saccade is subtracted from the current displacement feedback signal for one eye. This leads to disconjugate curvature for vertical saccades. As a result, the directional disconjugacy tended to increase for upward saccades and decrease for downward saccades.

Fig. 11.

Dynamics of directional saccade disconjugacy. The smoothed instantaneous difference in saccade direction (left-right polar direction) is plotted for simulated saccades in three directions (right, up, and down). The 3 models make very different predictions, indicating that the location of the crosstalk element has important consequences (see text for a detailed explanation).

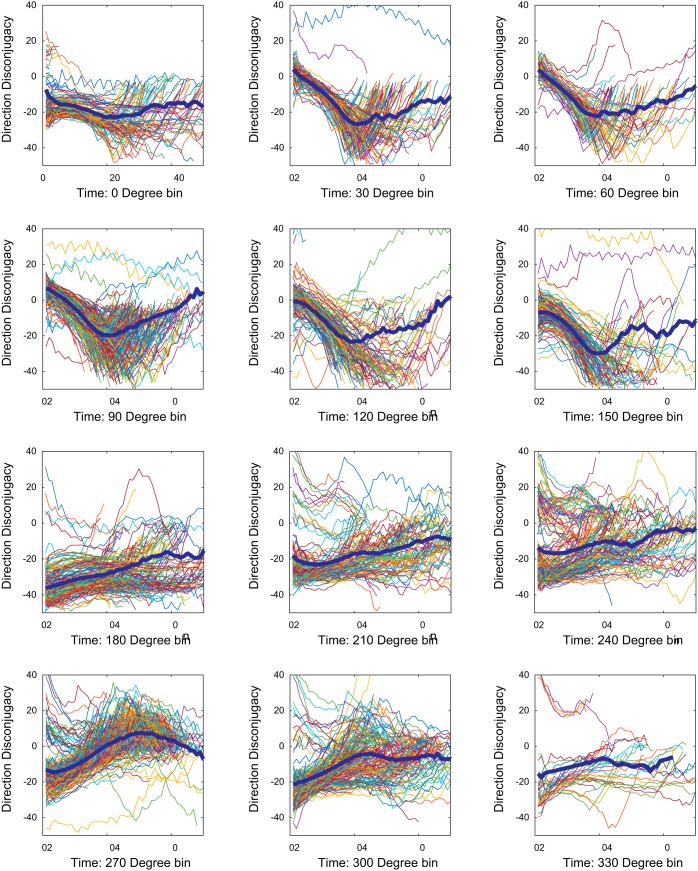

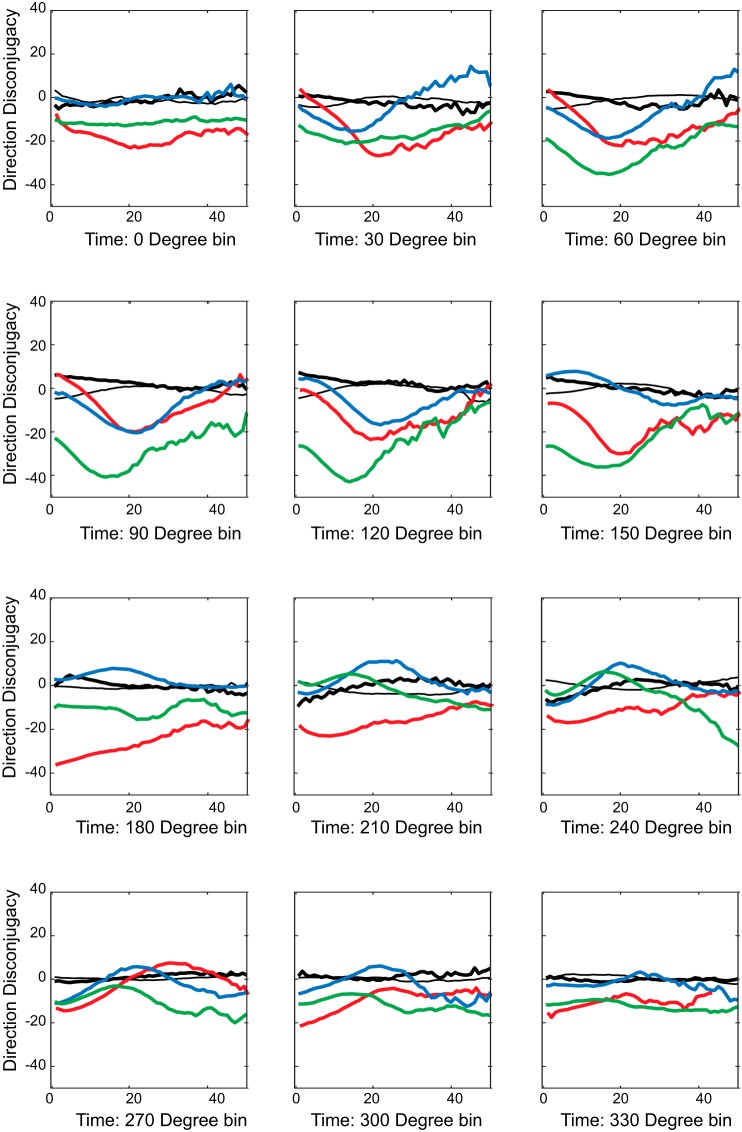

Next, we performed the same analysis on real saccades from monkeys N1, N2, ET1, ET2, and XT1. Figure 12 plots DD(t) as a function of time for saccades in each of the 12 direction bins in monkey XT1. Although there are many traces, some general trends can be observed. For all bins with a downward component, a large and consistent directional disconjugacy is apparent within the first 10 ms of the movement. For horizontal saccades (0° and 180° bins) the dynamic disconjugacy remained relatively constant for the duration of most saccades. For all direction bins with an upward component, the dynamic directional disconjugacy was initially small, or nonexistent, but then increased sharply. Figure 13 shows the mean DD(t) traces for all direction bins for all five monkeys. It is particularly noteworthy that, for two of the three strabismic animals, the initial directional disconjugacy was very small, or nonexistent, for all upward saccades, even though the overall directional disconjugacy was quite large. For all three strabismic animals the absolute value of DD(t) increased steadily until near the end of the movement; this was the case for all direction bins with an upward component. The more upward the direction, the more rapidly the directional disconjugacy increased. The direction reversals for DD(t) correspond to postsaccadic drifts, which were usually more conjugate than the saccades. For downward saccades (270° bin), DD(t) declined until near the time of saccade offset. This phenomenon rarely occurred in the normal animals.

Fig. 12.

CIdiff plotted as a function of time for 2,118 target-directed saccades for monkey XT1. All conventions are the same as in Fig. 13. For saccades with an upward component, the directional disconjugacy was initially small, or nonexistent, but then increased steadily until a few milliseconds before the end of the movement. For saccades with a downward component, the initial directional disconjugacy was usually large (>20°), but then declined steadily as the saccade progressed.

Fig. 13.

Mean values of CIdiff for all 5 monkeys. Traces from normal animals are shown in black. Red = monkey XT1; blue = monkey ET1; green = monkey ET2.

One potential concern is the possibility that passive orbital effects might influence the saccade trajectories for the two eyes in different ways when the initial positions differ. For example, elastic forces might cause a mild curvature for the abducted eye that would not be matched in the other eye if it was centered in the orbit. For monkey ET1, however, the initial horizontal strabismus angle was typically less than 5°, yet the changes in DD(t) for vertical saccades were similar to what we observed for monkey XT1 (who consistently had a horizontal strabismus angle > 25°). Indeed, we found no significant correlations between initial horizontal strabismus angle and CIdiff, for either upward (90° bin) or downward (270° bin) saccades, for any of the three subjects with strabismus.

DISCUSSION

With most pathological conditions there is a great deal of individual variability. Pattern strabismus is no exception; the cross-axis effects are mild in some patients and quite severe in others. For this reason it is not possible, even in principle, to estimate a crosstalk gain for one strabismic subject and use that value to predict saccade disconjugacy for all strabismic subjects. The present results, however, demonstrate that the dynamics of saccade disconjugacy follow a consistent pattern, at least for subjects with “A” patterns. The dynamics of directional disconjugacy presumably differ for subjects with “V” patterns.

Our simulations indicate that the location of the abnormal crosstalk element is important. Placing a single abnormal crosstalk within the local feedback loops fails to produce realistic directional disconjugacy, unless one assumes an implausibly large crosstalk gain (for monkey XT1, for example, the crosstalk gain of 0.9 would imply that PPRF neurons in this animal are driven almost as strongly by signals related to vertical velocity as horizontal velocity). This is because the monocular comparators dynamically adjust the ongoing component commands in an attempt to compensate for the addition of an inappropriate signal. Ultimately, this is the most serious problem with the Feedback Loop Crosstalk Model.

The Integrator Crosstalk Model and the Distributed Crosstalk Model assume an abnormally strong crosstalk between horizontal and vertical pathways in brain stem, downstream from the local feedback loop. Anatomic studies employing transsynaptic tracing with rabies virus have demonstrated monosynaptic projections from vertical eye movement regions riMLF and the interstitial nucleus of Cajal (INC) to abducens nucleus (Graf et al. 2002; Ugolini et al. 2006). Projections have also been demonstrated from the horizontal eye movement region, the nucleus prepositus hypoglossi (NPH) to INC, in squirrel monkey (Belknap and McCrea 1988). Thus evidence from several sources indicates that the potential is there for crosstalk between horizontal and vertical pathways, in ways that might not involve the local feedback loop.

For the Distributed Crosstalk Model, directional saccade disconjugacy is not the result of an abnormality at a single node within an otherwise normal circuit. Instead, this effect arises as a cumulative effect of abnormal directional tuning across the circuit as a whole. Dynamic changes in directional disconjugacy arise as a result of competing influences, coming into play at different times. For decades, many control systems models of the saccadic system have assumed that saccade amplitudes are controlled by a local feedback loop that dynamically compares a desired displacement command with a feedback signal related to current displacement. In our implementation of the Distributed Crosstalk Model, a signal related to the vertical component is subtracted from the current horizontal displacement signal, within the local feedback loop for one eye. Since the local feedback loops are assumed to be monocular, this means that the comparator for one eye receives inaccurate information regarding the current horizontal displacement. This leads to a difference in the horizontal velocity profiles between the two eyes, particularly late in the movement. This severity of this discrepancy is related to the amplitude of the vertical component and, thus, is essentially nonexistent for horizontal saccades. This leads to a difference in the amount of curvature of saccade trajectories for the two eyes which, in turn, translates to a systematic change in the directional disconjugacy as the saccade progresses. This particular assumption is really a special instance of the more general breakdown of directional tuning that defines this model.

Although the general patterns of saccade disconjugacy are clear, there is still some trial-trial variability in saccade disconjugacy (see Fig. 5). One potential explanation is suggested by studies showing that neurons in the supraoculomotor area modulate their activity in association with changes in horizontal strabismus angle in monkeys performing a smooth pursuit task on a tangent screen (Das 2011, 2012). If these neurons also modulate in association with a subset of saccades during the performance of our task, this might increase the variability of saccade disconjugacy. Recent studies have also provided evidence that rostral superior colliculus is involved in the realignment of the eyes at the end of disjunctive saccades in normal primates (Van Horn et al. 2013) and that abnormalities of rostral SC may influence eye misalignment in monkeys with strabismus (Upadhyaya et al. 2017). Thus the hypothesis that disordered slow vergence commands influence saccade disconjugacy deserves further testing.

Cross-Axis Smooth Pursuit Eye Movements

There are two possible explanations for the fact that cross-axis movements are observed for both saccades and smooth pursuit. First, it may be that separate crosstalk elements exist for different oculomotor subsystems. This idea posits that misalignment of the eyes early in life disturbs the development of directional tuning for different oculomotor systems in similar ways. If this is the case, it seems likely that the crosstalk gains would differ for saccades and smooth pursuit (for at least some subjects with pattern strabismus).

Alternatively, the crosstalk might occur at a level shared by multiple oculomotor subsystems. This might occur at the level of nucleus prepositus hypoglossi (NPH) and the interstitial nucleus of Cajal (INC). Modelers typically treat NPH and INC as simple, perfect integrators but this is an oversimplification of the role of very complex structures. For example, many neurons in these structures exhibit burst-tonic properties when monkeys perform a saccade task (Fukushima et al. 1990; Fukushima and Kaneko 1995; McFarland and Fuchs 1992). Thus crosstalk at this level could, potentially, affect the dynamics of saccades, as well as static eye position. Numerous studies have shown that NPH and INC serve as neural integrators for multiple oculomotor subsystems, including saccades, smooth pursuit, vergence, and the VOR (Belknap and McCrea 1988; Cullen et al. 1993; Dale and Cullen 2013; Fukushima and Kaneko 1995; Kaneko 1999; McCrea and Horn 2006; Sylvestre et al. 2003). The Integrator Crosstalk Model predicts that saccades, smooth pursuit, and the VOR exhibit directional disconjugacy in pattern strabismus because signals for all of these eye movements pass through the same disordered integrators. A potential advantage of the Integrator Crosstalk Model is that it provides a simple explanation for the fact that directional disconjugacy is observed for both saccades and smooth pursuit.

Developmental Perspectives

Disruption of binocular vision during the first weeks of life reduces the proportion of binocularly responsive units in V1 (Crawford and von Noorden 1979; Kumagami et al. 2000; Mori et al. 2002), MT (Kiorpes et al. 1996) and MST (Mustari et al. 2008) and some brain stem centers (Mustari et al. 2001). Binocular visual cortical centers distribute signals directly to brain stem nuclei like the SC and the nucleus of the optic tract (NOT) and indirectly through the cerebellum. These circuits convert visual signals into commands for binocularly coordinated eye movements.

In strabismus binocular coordination could be compromised through failure to develop normal binocular and disparity sensitive neurons in V1 and extrastriate visual areas, thus depriving brain stem centers of important sensory and error-correcting signals. This defect is associated with impaired binocular coordination and the presence of disconjugate eye movements. In infancy, if there are horizontal and vertical misalignments of the visual scene the cerebellar floccular complex may receive inconsistent error signals from the two eyes during a crucial period for the development of directional tuning in brain stem neurons related to eye movements.

In pattern strabismus, visual information derived from specific areas of the retina appears to be suppressed (Sireteanu 1982; van Leeuwen et al. 2001). In monkeys with exotropia induced in infancy (Agaoglu et al. 2014), and in humans with intermittent exotropia (Economides et al. 2012, 2014) the suppression affects signals originating in the temporal hemiretina. There is also evidence that signals from some portions of the nasal hemiretina may be suppressed in esotropia (Agaoglu et al. 2014; Brodsky and Klaehn 2017; Joosse et al. 1997; Pratt-Johnson and Tillson 1984; Sireteanu 1982). Such suppression might interfere with calibration of brain stem centers involved in precise control of conjugate eye movements.

We suggest that visuomotor neurons in the intermediate layers of the SC are driven by monocular visual cortical signals and may be influenced by differing patterns of suppression for the two eyes. This abnormal situation might lead to the distortions of the SC motor maps assumed by the Distributed Crosstalk Model. This, in turn, could affect the spatial-temporal transformation that determines the velocity signals carried by saccadic premotor burst neurons in PPRF and riMLF, such that the direction and velocity would differ for the two eyes. Consistent with this idea, both single unit recordings and microstimulation of PPRF have provided evidence that this structure carries abnormal directional signals in pattern strabismus (Walton and Mustari 2015; Walton et al. 2013).

The mathematical integration of monocular, disconjugate component velocity signals in nucleus prepositus hypoglossi and the interstitial nucleus of Cajal would lead to eye position signals that differ for the two eyes. This prediction has not been tested in strabismic monkeys performing a saccade task, but recordings from horizontal and vertical rectus motoneurons have revealed an analogous effect for strabismic monkeys performing a smooth pursuit task (Das and Mustari 2007; Joshi and Das 2011). These recent studies provide a framework for future work that could more fully define the neural mechanisms responsible for oculomotor abnormalities in strabismus.

It is unlikely that manipulations during the first week of life would cause neuroanatomical pathways to grow that are not found in normal monkeys. However, disruption of binocular vision early in life might lead to a retention of horizontal-vertical cross-connections that are normally lost. Indeed, it has been suggested that anatomical connectivity between horizontal and vertical pathways in brain stem might serve an adaptive role (Graf et al. 1993; Schultheis and Robinson 1981; Ugolini et al. 2006). Selective, experience-dependent pruning of these connections may help to ensure that signals sent to horizontal and vertical rectus muscles are appropriate, given individual variability in the growth patterns of extraocular muscles and orbital tissues. When the visual fields of the two eyes are vertically misaligned for extended periods early in life, this process may not occur normally, leaving inappropriately strong cross-connectivity between horizontal and vertical pathways. Consistent with this idea, rearing infant monkeys with prism goggles or alternating monocular occlusion is sufficient to cause a permanent pattern strabismus (Das et al. 2005; Walton et al. 2014). Thus we are proposing an element that might be functionally weak in normal animals but abnormally strong in pattern strabismus.

One of the challenges of modeling saccade disconjugacy in strabismus is finding a way to reconcile the fact that saccades are disconjugate with the observation that humans and monkeys with strabismus are able to make accurate saccades with either eye fixating (Das 2009; Economides et al. 2014). This basic problem exists, regardless of the underlying cause of the disconjugacy. For example, even if the saccadic system was 100% conjugate and binocular in strabismus, and disconjugacy resulted only from muscle abnormalities, it would still be necessary for the brain to issue different commands to satisfy a given desired displacement, depending on which eye was viewing. For example, suppose the medial rectus muscle for the left eye is abnormally weak in a given monkey (or human patient). Even in that case, a different command would be needed to generate a 10° rightward saccade for the left eye (when that eye is viewing) than a 10° rightward saccade for the right eye (when that eye is viewing).

Thus it seems unavoidable that the brain somehow takes the disconjugacy into account to ensure that either eye can be accurately brought to the target. We believe that the most likely explanation is that the brain switches between different adaptive states, depending on which eye is viewing the target. Other examples of context-specific saccadic adaptation are known, based on factors such as initial eye position, viewing distance, or head tilt (Chaturvedi and van Gisbergen 1997; Shelhamer et al. 2005; Shelhamer and Clendaniel 2002).

One possibility is that the cerebellum is able to switch between different adaptive states, depending on which eye is fixating. For example, the saccadic burst could be enhanced if the fixating eye is the one with a smaller burst generator gain, and reduced if the fixating eye is the one with a larger gain. Because saccade adaptation is binocular in strabismus (Das et al. 2004), directional and amplitude disconjugacy would still be observed, even though the subject can accurately bring either eye to a visual target. Other examples of context-specific saccadic adaptation are known, based on factors such as initial eye position, viewing distance, or head tilt (Chaturvedi and van Gisbergen 1997; Shelhamer et al. 2005; Shelhamer and Clendaniel 2002). Thus any directional error for the viewing eye would be corrected by conjugate (Das et al. 2004) saccadic adaptation. We do not know whether abnormal crosstalk affects both eyes, or only one (i.e., the nonpreferred eye?). Mathematically, the models will produce the same output whether one assumes that the viewing eye is unaffected by any crosstalk, or that crosstalk produces a directional error that (for the viewing eye) is compensated by conjugate adaptation. There is evidence for a role of cerebellum in the maintenance of eye misalignment in strabismus. Reversible inactivation of caudal fastigial nucleus and posterior interposed nucleus result in changes in horizontal strabismus angle (Joshi and Das 2013).

We suggest that the loss of binocular coordination during a sensitive period early in life (whatever the cause) disrupts the developmental refinement of synaptic weights. This leads to abnormalities in brain stem oculomotor circuits which can (at least partially) account for patterns of saccade disconjugacy. If one or more of the eye muscles is weak then parameter estimates derived solely from behavior might overestimate the gain imbalances for the burst generators. However, as discussed above, there is compelling evidence for abnormalities at the neural level. Therefore, despite the uncertainties about the specific values of behaviorally derived parameter estimates, the underlying principles remain valid.

Torsion

It is well known that human patients with pattern strabismus often show abnormal torsion. However, there is compelling evidence that this phenomenon is not obligatorily related to saccade disconjugacy. First, Ghasia et al. (2015) directly compared ocular torsion and directional saccade disconjugacy in human patients with pattern strabismus. They found no correlation between the two, and concluded that cross-axis saccade disconjugacy is likely attributable to abnormally strong crosstalk between horizontal and vertical neural pathways. Second, torsional abnormalities are not always found in human patients with pattern strabismus. Deng et al. (2013) reported that 76% of human patients with A-pattern strabismus showed intorsion; 71.1% of patients with V-pattern strabismus showed extorsion. Thus, although torsional deviations are common in human patients with pattern strabismus, this particular abnormality is not always present. These studies indicate that torsional abnormalities are not obligatorily related to directional saccade disconjugacy in pattern strabismus.

We were unable to measure torsion in our monkeys with pattern strabismus. This makes it impossible to quantitatively compare torsion in our models with the observed behavior in our subjects. Nonetheless, these models can be easily extended to produce abnormal torsion. For example, premotor saccade-related neurons in the rostral interstitial nucleus of the medial longitudinal fasciculus project to both vertical rectus and oblique muscle motoneurons (Moschovakis et al. 1991a, 1991b). A central assumption of our models is that saccade disconjugacy is partially attributable to gain imbalances within brain stem. Given the above neuroanatomical projections of riMLF neurons it is easy to see how this mechanism could, potentially, generate abnormal torsion. If the connection weights at the inputs to oblique muscle motoneurons are unbalanced, then abnormal torsion will result. On the other hand, if these connection weights are relatively normal, a patient with pattern strabismus may not exhibit abnormal torsion.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institues of Health Grants EY-024848 (M. M. G. Walton), EY-06069 (M. J. Mustari), and ORIP-P51-OD-010425.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.M.W. conceived and designed research; M.M.W. performed experiments; M.M.W. analyzed data; M.M.W. and M.J.M. interpreted results of experiments; M.M.W. prepared figures; M.M.W. drafted manuscript; M.M.W. and M.J.M. edited and revised manuscript; M.M.W. and M.J.M. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Greg Anderson, Bob Cent, Bob Smith, Renae Koepke, and Bill Congdon for technical assistance. We are also grateful to Dr. John van Opstal for helpful comments on a first draft of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Agaoglu MN, LeSage SK, Joshi AC, Das VE. Spatial patterns of fixation-switch behavior in strabismic monkeys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 55: 1259–1268, 2014. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker W, Jürgens R. Human oblique saccades: quantitative analysis of the relation between horizontal and vertical components. Vision Res 30: 893–920, 1990. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(90)90057-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belknap DB, McCrea RA. Anatomical connections of the prepositus and abducens nuclei in the squirrel monkey. J Comp Neurol 268: 13–28, 1988. doi: 10.1002/cne.902680103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky MC, Klaehn LD. An optokinetic clue to the pathogenesis of crossed fixation in infantile esotropia. Ophthalmology 124: 272–273, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucci MP, Kapoula Z, Yang Q, Roussat B, Brémond-Gignac D. Binocular coordination of saccades in children with strabismus before and after surgery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 43: 1040–1047, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busettini C, Mays LE. Saccade-vergence interactions in macaques. II. Vergence enhancement as the product of a local feedback vergence motor error and a weighted saccadic burst. J Neurophysiol 94: 2312–2330, 2005. doi: 10.1152/jn.01337.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi V, van Gisbergen JA. Specificity of saccadic adaptation in three-dimensional space. Vision Res 37: 1367–1382, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0042-6989(96)00266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford ML, von Noorden GK. The effects of short-term experimental strabismus on the visual system in Macaca mulatta. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 18: 496–505, 1979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen KE, Chen-Huang C, McCrea RA. Firing behavior of brain stem neurons during voluntary cancellation of the horizontal vestibuloocular reflex. II. Eye movement related neurons. J Neurophysiol 70: 844–856, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale A, Cullen KE. The nucleus prepositus predominantly outputs eye movement-related information during passive and active self-motion. J Neurophysiol 109: 1900–1911, 2013. doi: 10.1152/jn.00788.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das VE. Alternating fixation and saccade behavior in nonhuman primates with alternating occlusion-induced exotropia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 50: 3703–3710, 2009. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das VE. Cells in the supraoculomotor area in monkeys with strabismus show activity related to the strabismus angle. Ann NY Acad Sci 1233: 85–90, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06146.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das VE. Responses of cells in the midbrain near-response area in monkeys with strabismus. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 53: 3858–3864, 2012. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-9145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]